The implementation of the NEPBE: Including English as a subject in Mexico in elementary education

Including English as a subject in elementary education is a common practice among countries around the world. Governments in Costa Rica, Thailand and Italy have taken actions to implement English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in elementary levels (Nunan, 1999). In Mexico, English has been a compulsory subject in public secondary schools for over thirty years. In 2009, the Secretaría de Educación Pública (National Ministry of Public Education) started the National English Program in Basic Education (NEPBE) to include EFL in primary education. At its pilot stage, this program provided EFL instruction from third grade in preschools to sixth grade in primary school. The first Federal Entities in integrating this program were: Aguascalientes, Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Tamaulipas. Nowadays, the program has expanded along the country and the interest in exploring the situation of the program has generated extensive research. In Ramírez, Pamplón, and Cota (2012) national research, which included 11 states, found that the areas in which work was needed for the proper implementation of the NEPBE was in the curriculum, the teachers (characteristics, current labor situation, and profile), the teaching /evaluation practices, and the resources and materials. Their study brings to light the complexity of the situation throughout the country. The present work reports the findings of a small scale qualitative research in the state of Puebla. The report includes a brief review of the literature related to the rational for the implementation of the NEPBE and the requirements for a successful implementation. The methodology used for the research and the findings are presented followed by a discussion of the implications of the results.

The rationale for the NEPBE

There are several reasons to support the initiative to implement the NEPBE. One of them is the shared perception that the earlier EFL instruction is provided, the greater the benefits (Krashen, Long, & Scarcella, 1979). In terms of pronunciation, for example, there is evidence that learners pronounce more accurately when instruction begins at an early age (Flege, 1999; Harley, 1986; Harley & Wang, 1997; Scovel, 1988). Another reason is the belief that an early start may foster a positive attitude and cultural awareness about the language being learned by the young learners. To this respect, Pinter (2006, p. 38) points out that “the second main aim [of an early implementation] is related to the need to make English an attractive school subject to children so as to foster their motivation…”. As a third argument, there is evidence that children develop cognitive and meta linguistic skills, which help them in other areas of their First Language (L1) education (Armstrong & Rogers, 1997). Finally, Nunan (1999) also claims that early EFL instruction brings benefits in terms of further professional development and economic growth not only at the individual level but also to the nation. All in all, the advantages of implementing an English program for young learners are numerous. Yet, many prior considerations need to be taken in order to maximize the chances of a successful implementation.

Requirements for a successful implementation

Extensive research has been carried out in relation to the implementation process of innovations in English Language Education (ELE) (Clark, 1987; De Lano, Riley & Crookes, 1994; Markee, 1992; Markee, 1997, Rogers, 2003; Waters & Vilches 2001; Waters & Vilches, 2008). The concept of innovation implies change (Wedell, 2009 cited in Waters, 2009). This change is, first of all, seen as potentially beneficial and emerges from the dissatisfaction with the current situation (Kennedy, 1988 cited in Waters, 2009).

The motivation for the promoting of innovation may be political, economic or bureaucratic (Cooper 1989, as cited in Waters, 2009). However, regardless of what the motivations are, the implementation of an innovation in ELE requires several aspects to be considered. The aspects that are considered may be divided into two broad categories. On the one hand, at the classroom level (micro), the pertinence of the program in accordance with the learners’ characteristics and the teachers profile are of paramount importance. In the case of the NEPBE at this micro level, it is important to highlight that “young learners tend to have short attention spans, […] a lot of energy, […] are very much linked to their surroundings, and are more tangible” (Shin, 2006, p. 3). Because of these and other characteristics of children, working with them is a highly demanding task. Therefore, teachers need to “…re-think their approach when teaching children” (Read 1998, p. 8) and it is also necessary for language teachers “[…] to be knowledgeable about second language acquisition, especially in children, and about appropriate second language teaching strategies and practices” (Curtain & Dahlberg, 2000, p. 2). In this line of argumentation, the planning of the program and the teachers profile may, or may not, contribute to the success of the NEPBE.

On the other hand, the broader socio-economic and political (macro) circumstances have an impact on the implementation of a program as well. The pertinence of the ELE program in relation to the current curriculum and the support from the government, the educational authorities and the community are determinant for its success. To this respect, Pinter (2006) states, “…local governments and authorities need to consider issues such as the characteristics of their educational system, […] how far the primary curriculum can be integrated with English, and how much they can afford to spend on teacher education […]” (p.42). In the case of the NEPBE, its implementation is shaped by the current educational circumstances, determined by the National Ministry of Public Education, and the budget assigned (by the government) for the project. The lack of congruency between the expectations of the implementation and these conditions results in detriment of the implementation.

Finally, Shin (2006) suggests “it is […] important for those in the [Teaching English to Young Learners] TEYL profession to stay connected with each other and with the local community […]” (p. 13). In other words, not only teachers need to be in constant communication but the community must also do its part. To this regard, there is also evidence that the community may also affect the implementation of a program. Parents, for example, play an important role in the acceptance of the program as well (Christensen & Cleary, 1990; Hara & Burke, 1998; Loucks, 1992).

In sum, Nunan (1999) suggests that ELE programs “need to be carefully planned, adequately supported and resourced, and closely monitored and evaluated” (p. 3). The program and the current curriculum circumstances, the teachers profile, the students’ characteristics, the government, and the community support are all important. In all the process of the implementation it is important to maintain a constant interrelation among those involved. In other words, it is important to involvethe school administrators, principals, parents and other teachers in order to facilitate the implementation of the NEPBE.

Methodology

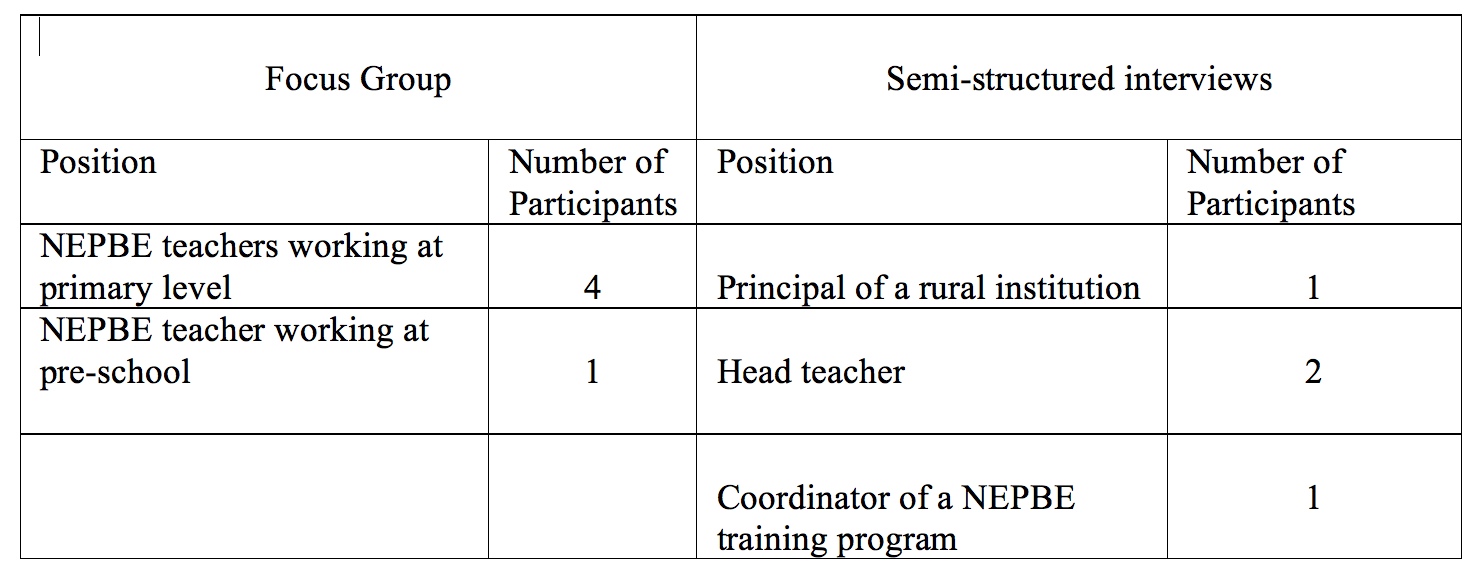

The methodology used for this research is qualitative in nature. Nine participants playing different roles in the implementation of the NEPBE were part of the study. The data gathering was done through open-ended interviews and a focus group. In the case of the individual interviews, the participants were a principal at a rural school, two head teachers from two different rural schools, and the coordinator of a training program for NEPBE teachers. The use of semi-structured interviews allows the researcher and participants to explore topics that are important or relevant for the interviewees and the researcher. In this sense, the data is richer than if the interview is limited to the researcher’s preconceptions (Richards, 2005; Hancock, 2002; Arthur and Nazroo, 2003).

The participants of the focus group were five female teachers whose ages ranged from 21 to 27. By the time the focus group was carried out all of the participants had worked for the NEPBE, in different institutions, for at least one year. Four of them had been working at elementary level and the other in pre-school level. According to Kitzinger (as cited in Krzyzanowski, 2008, p. 162), focus groups enable the researcher to “explore a specific set of issues such as people’s views and experiences.” In addition, focus groups offer the advantage that participants may feel more confident when giving their opinions (Krzyzanowski, 2008). The table below (fig. 1) shows the organization of the participants:

Fig. 1 Participants and data gathering

The interviews and the focus groups were recorded with the prior consent of the participants. For the analysis, the data was transcribed, coded and, categorized. The process was systematized to find general categories and subcategories (Richards, 2005; Dey, 1993). Coding was done by assigning general labels to the information provided by the participants to generate general categories. These categories were then grouped into subcategories. In the cases where no more than three mentions were present, the categories were eliminated. In general the process was done in a zigzag fashion by going back and forth from the data to the categories (Creswell, 1998) and then being peer reviewed by both authors of the present research to validate the categories.

Findings

The non-academic aspects that affect the implementation of the NEPBE found were categorized into three main sections: Administrative issues, Misconceptions, and Reluctance to integrate the NEPBE. This section describes those aspects.

Administrative issues

Based on the data gathered from the interviews and the focus group, the participants identified several administrative factors that seem to impede a successful implementation of the NEPBE in their contexts. Participants found similar results to those of Ramírez, Pamplón, and Cota (2012), in this study the most salient factors that emerged from the analysis which constrain the implementation of the NEPBE in Puebla are the lack of payment, the lack of proper conditions in terms of the facilities, resources and, equipment, and the lack of prior specialization in the field of TEYL.

Payment

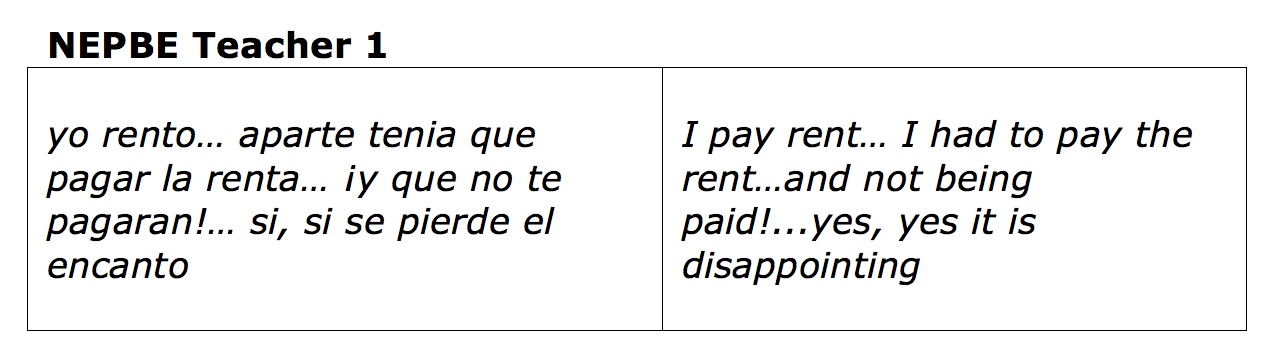

At this point it is important to mention that, since NEPBE still remains at its pilot stage, payment in the state of Puebla has been unstable. The Coordinator of the NEPBE training program commented that this is due to the fact that the program is in the pilot stage and that the NEPBE teachers were not hired directly by the National Ministry of Public Education in the state of Puebla. Therefore, although many EFL teachers joined the program with very high expectations to, one day, become public education teachers and get all the payment and health care benefits of an official teacher, this has not been the case. As a result, many NEPBE teachers have developed mixed feelings towards the program that seem to have affected their commitment to the program. During the focus group, teachers expressed their concern about payment arguing that they were only paid six months after they had started working. Teachers also complained that they were told that they would be paid in December but were not paid until July. They also commented that in some occasions they did not afford (as they had not been paid) to commute from their homes to they workplaces. One of the NEPBE teachers expressed her feelings of disappointment, as she did not have the money to pay the rent as seen in the extract below:

Although it cannot be argued that salary is the only factor that could determine the success or failure of a program, the results indicate that the irregularity in which NEPBE teachers have been paid has a negative impact on teachers’ commitment towards the program. This also implies that the recommended conditions for the implementation of an ELE program suggested by Clark, 1987; De Lano, Riley & Crookes, 1994; Markee, 1992; Markee, 1997, Rogers, 2003; Waters & Vilches 2001; Waters & Vilches, 2008 have been, at least partially disregarded, from the perspective of the participants of the study.

Working conditions (resources, equipment, and facilities)

As has been explained before, the implementation of EFL program needs to be well planned and resourced from an early stage (Nunan, 1999). This means that proper working conditions need to be assured. For example, adequate facilities, resources, and equipment are crucial for the success of the program. However, the NEPBE teachers have still had to face issues related to this topic. In some instances NEPBE teachers found large groups in small classrooms. Teachers also mentioned that they had to pay for the materials they wanted to use in their classes. Materials such as flashcards, posters, and handouts had to be purchased by the teachers. In some cases, they report that they had to take their own tape recorders to their classrooms because the institution did not provide one for them. These results show that the case in Puebla is similar to those cases researched in Ramírez, Pamplón, and Cota (2012) in regards to issues with materials and facilities.

Prior Specialization in the field of TEYL

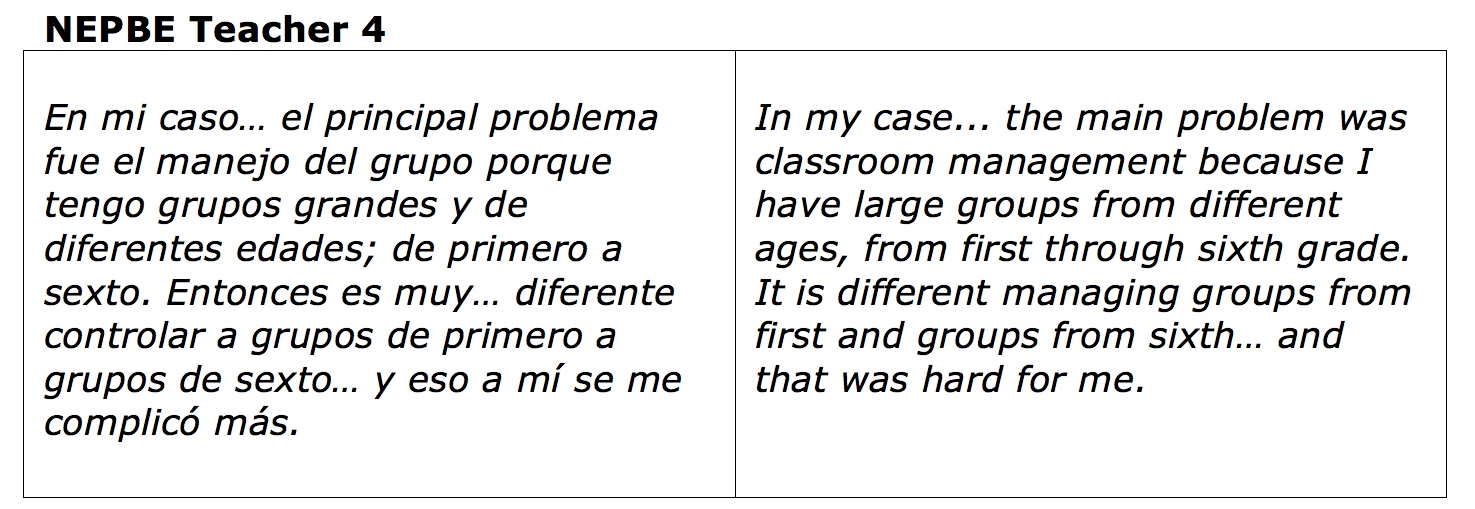

Another factor related to administrative aspects is the selection and training of teachers for the implementation of the NEPBE. As previously stated, one of the requirements for success is the role of the teachers (Nunan, 1999; Pinter, 2006) and their need to be capable and specialized in the field of TEYL (Curtain & Dahlberg, 2000; Read, 1998; Shin, 2006). In the case of Puebla, all of the teachers selected held a BA in ELT. However, it seems that, at least, the participants of the focus group needed more training and specialization in TEYL, more specifically more training in classroom management. Those teachers expressed that they struggled to manage large groups as can be seen in the following extract

This suggests that holding the BA in ELT may not be sufficient and more teacher training actions and programs are needed for the success of the NEPBE as suggested by Pinter (2006).

Misconceptions

In addition to the non-academic administrative factors that affect the implementation of the NEPBE, non-academic factors related to misconceptions, from head teachers, school principals, and administrators about the program seem to have also had a negative impact on its implementation. Two major misconceptions that emerged from the analysis included misconceptions about the nature of the NEPBE and the perception that ELT as a waste of time. These categories will be discussed in the following subsections.

Nature of the NEPBE

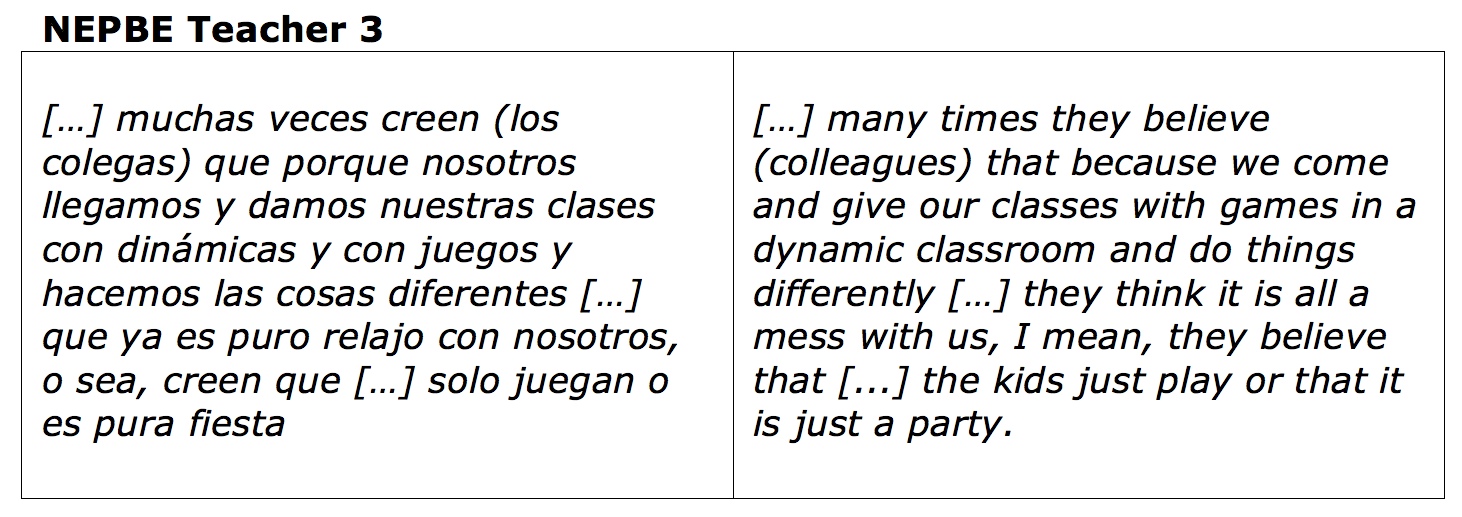

Making English fun and accessible is one of the guiding principles of the NEPBE (National English Program in Basic Edication, 2010). As a result of immersion in training programs, many NEPBE teachers have incorporated such principles into their teaching. However, this practice is not always regarded as a positive characteristic by the traditional model of education. Yet NEPBE teachers have the feeling that traditional teachers and institutions view the inclusion of ludic activities in English classes as an undesirable practice. The following excerpt shows an example of this issue.

As can be observed, there seems to be a misconception regarding the approach that NEPBE teachers have adopted to familiarize students with English. NEPBE teachers report that some school principals and head teachers seem to discredit the use of ludic activities within their classrooms and schools. Moreover, the English class seems to be regarded as a time for students to play and head teachers to relax as reported by the participants of the focus group.

EFL instruction as a waste of time

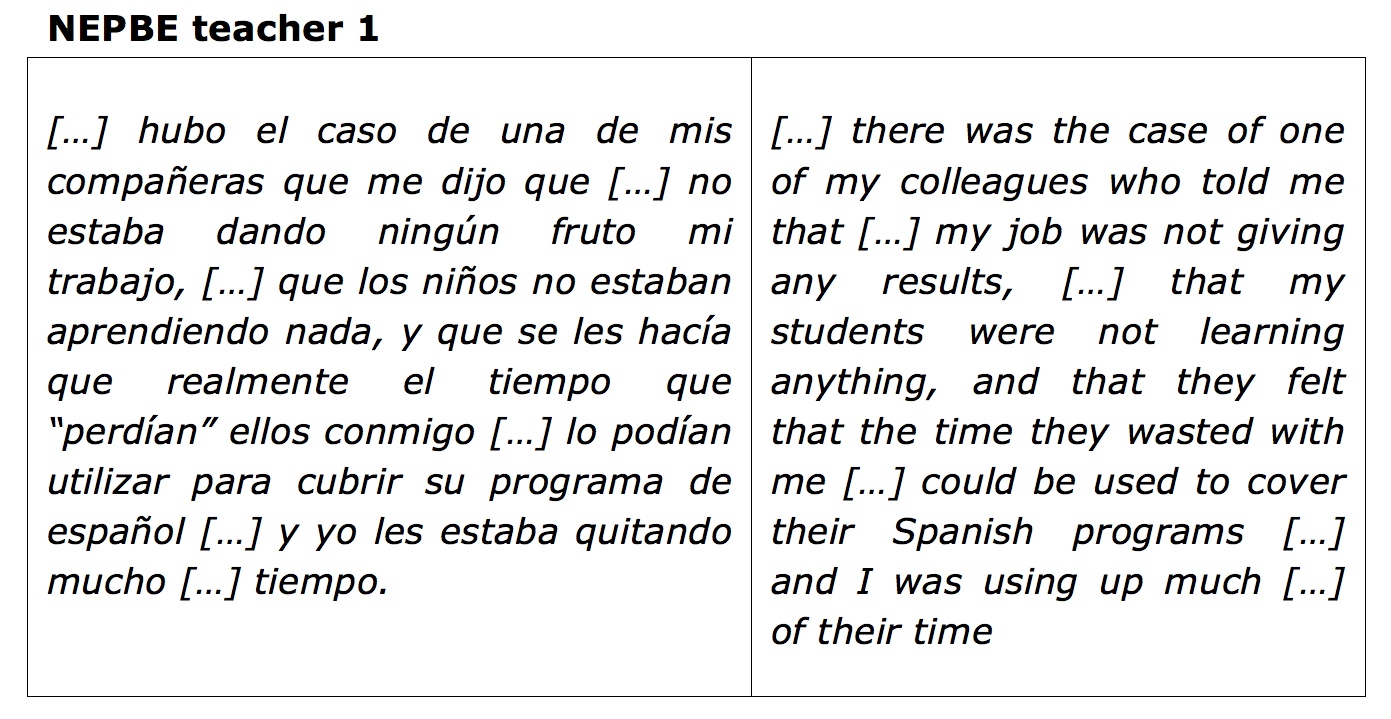

Another salient misconception that affects the implementation of the NEPBE is the idea that EFL instruction, at an early age, not only distracts students from “important” classes (i.e. Math, Science, and Spanish) but that it is also a waste of time. Contrary to what the evidence suggests (Armstrong & Rogers, 1997; Flege, 1999; Harley, 1986; Harley & Wang, 1997; Nunan, 1999; Pinter, 2006; Scovel, 1988), NEPBE teachers reported that head teachers perceived the inclusion of the NEPBE as a waste of time. This is illustrated in the extract below:

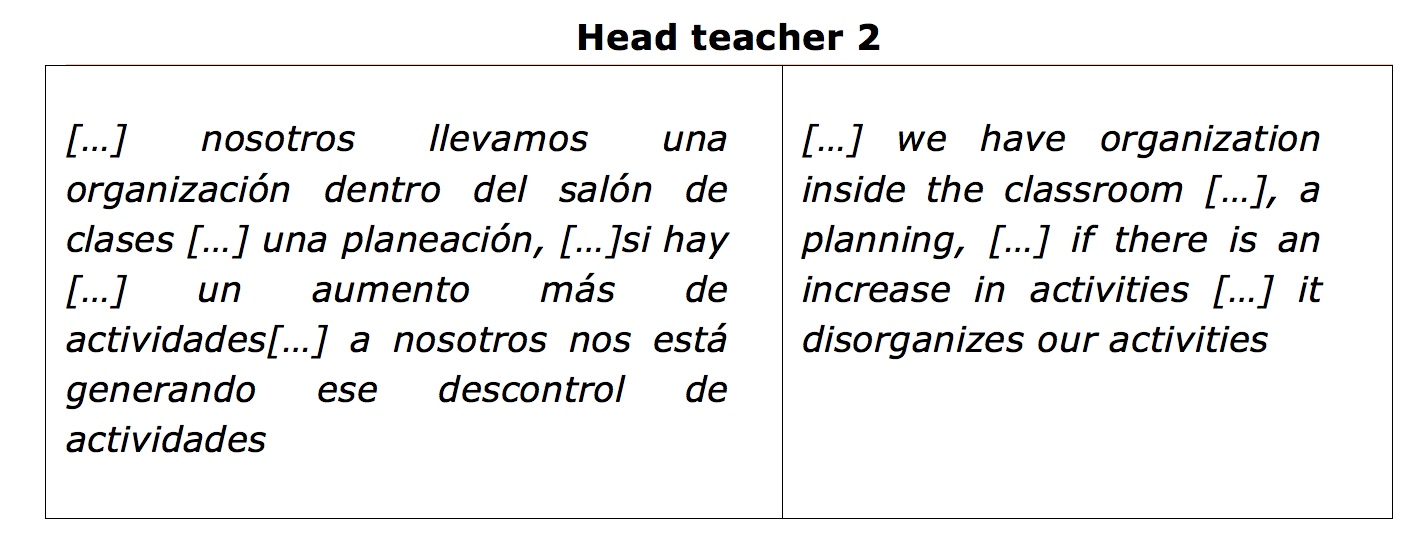

The misconception that teaching English to young learners distracts students from the important content areas among head teachers is not the only problem. The NEPBE program also generates a tense environment for head teachers since including extra activities requires head teachers to reorganize their activities in order to cover their programs. The extract below shows this tension.

This shows that for head teachers the NEPBE represents inconveniences since they have to make changes in their planning to cover their programs. Although this may suggest a lack of congruency between the current curriculum and the inclusion of the NEPBE, which as discussed before is of paramount importance (Pinter, 2006), further research is needed to explore the reasons for this constrain.

In sum, these misconceptions bring to light the need to take into account the suggestions of the implementation requirements (Waters & Vilches 2001; Waters & Vilches, 2008; Waters, 20009) in order to find alternatives to disseminate the purpose and nature of the NEPBE among those involved in the process. Being connected (Shin, 2006), may contribute to overcome this issue and facilitate the inclusion of English in elementary education.

Reluctance to integrate the NEPBE

The last category that was found in the analysis is what we called reluctance to integrate the NEPBE. In general, it was found that to some extent, there is a rejection to implement the NEPBE on the part of principals, parents, and head teachers.

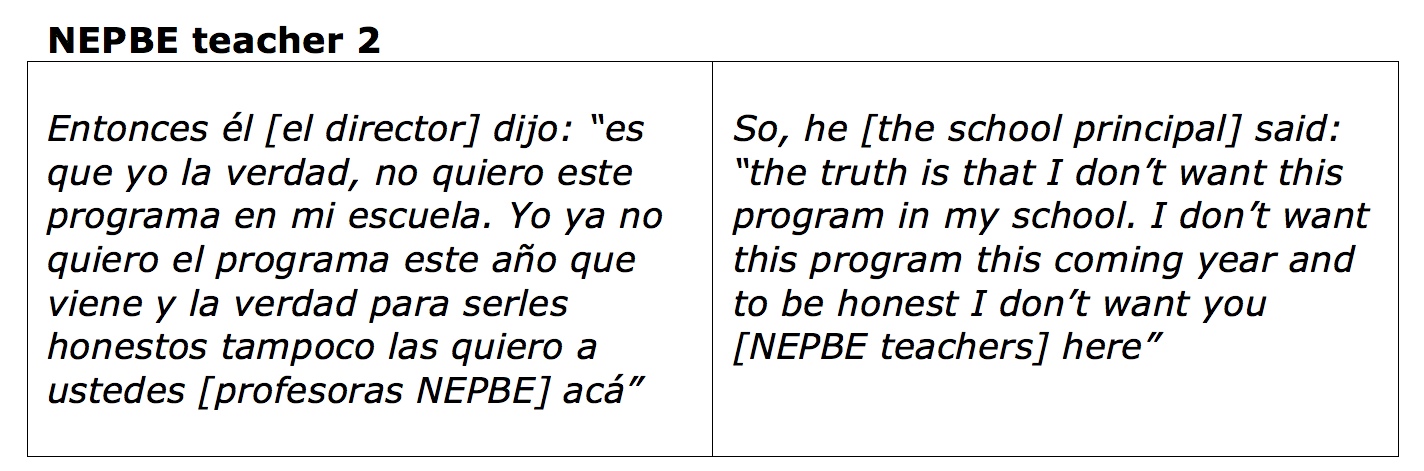

Despite of the fact that they hold official letters of introduction into the school they were assigned to collaborate with, NEPBE teachers have had to negotiate being accepted. In the analysis of the focus group it was found that one of the school principals directly expressed his rejection to the program and to one of the NEPBE teachers. The following excerpt shows this issue.

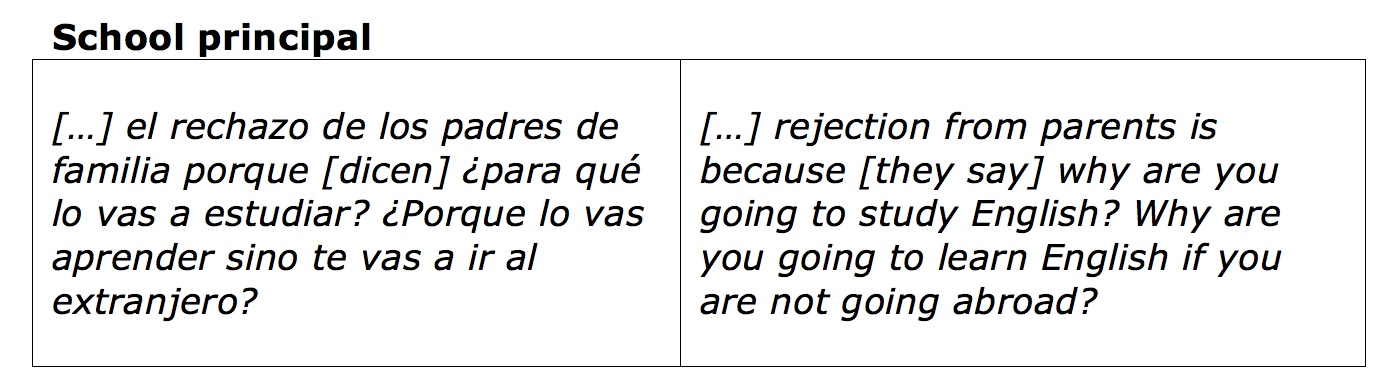

In the same way, the principal of the rural school commented during the interview that parents perceive the inclusion of English as a waste of time as parents do not see the usefulness if their children are not going to travel abroad. The extract below illustrates this issue.

As noted in this extract, parents’ perceptions towards the NEPBE may influence the implementation of the NEPBE. To this respect, parental involvement (Christensen & Cleary, 1990; Hara & Burke, 1998; Loucks, 1992) may be an alternative to be taken into account to ease the acceptance of the NEPBE.

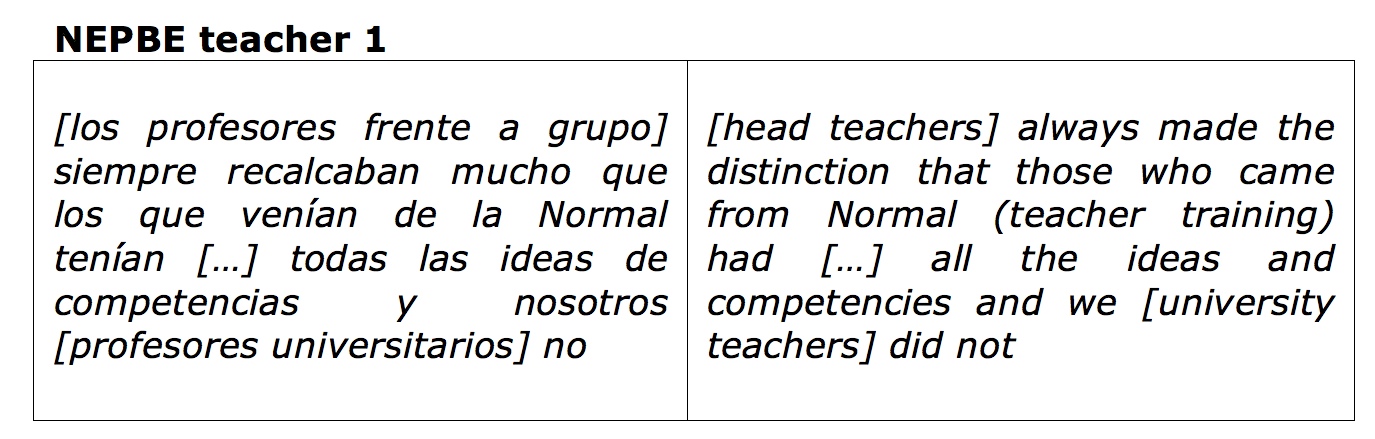

The last factor that seems to have a negative impact on the implementation of the program is the perception that head teachers have about the NEPBE teachers in terms of academic background. As it was mentioned before, one of the requirements to become a NEPBE teacher was to hold a BA in ELT. In Puebla, there are two possibilities to obtain a BA in ELT, public and private universities and the normal superior (teacher training school). This distinction seems to have an impact on the acceptance of those NEPBE teachers who obtained their degree from a university. This might be due to the fact that all the head teachers studied at the normal (teacher training). In this regard, one of the NEPBE teachers commented the following:

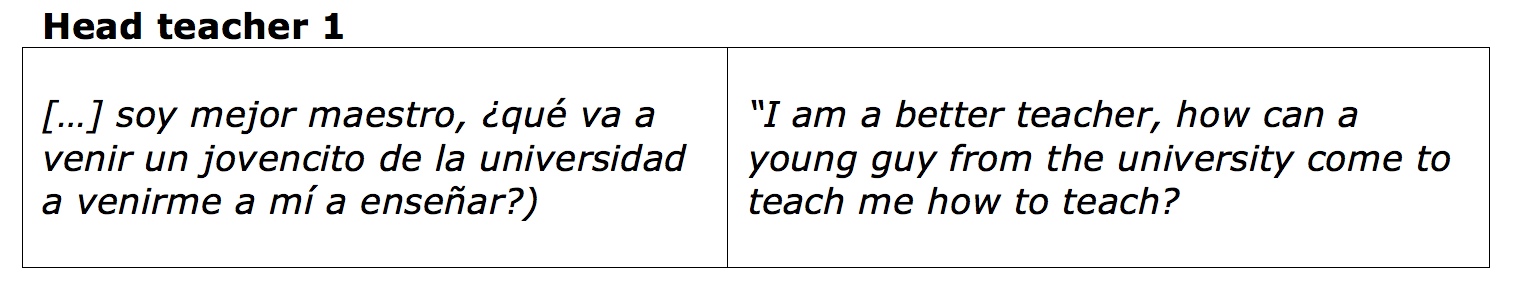

This distinction between the two groups was not only perceived by NEPBE teachers; while interviewing one of the head teachers it was revealed that some colleagues (other head teachers) made comments such as:

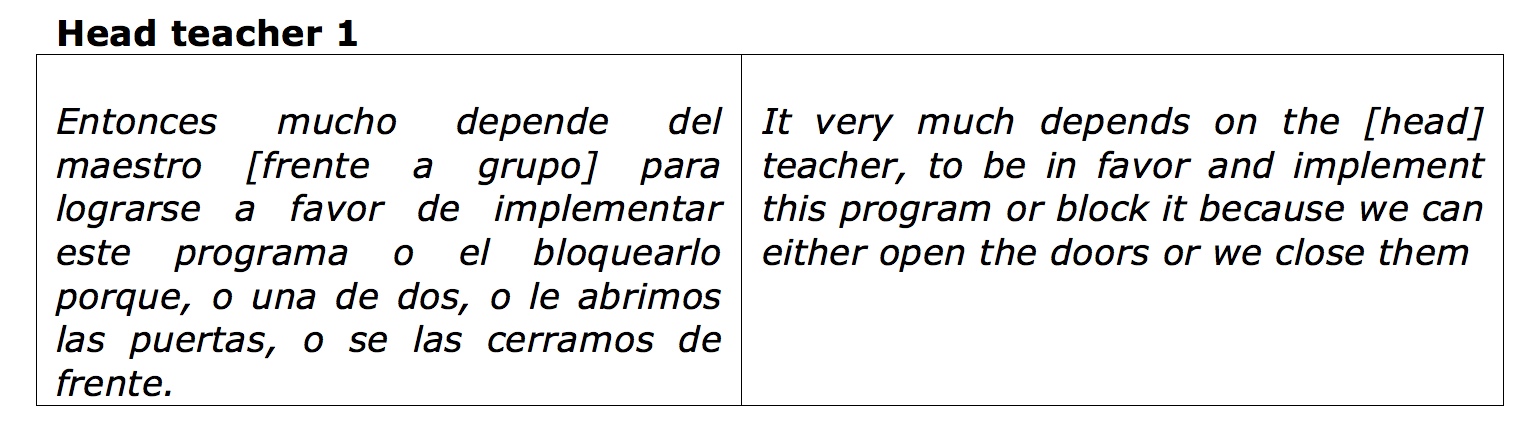

As can be observed, the extract shows the use of young guy from the university to make the distinction between the NEPBE teachers and the head teachers coming from Normales (teacher training). This tension between head and NEPBE teachers is a potential drawback for the implementation of the program. The same head teacher acknowledges this as she commented that head teachers may open or close the doors for NEPBE teachers as noted in the extract below:

The excerpts above presented show how difficult it could be to gain entry into the school for NEPBE teachers. The role of the administrative staff (principals), parents, and head teachers, as suggested above (Shin, 2006), seems to be extremely important for the implementation of the NEPBE. The difficulty to become accepted does not necessarily have to do with the teachers’ professionalism or the unofficial status of the program. On the contrary, it seems to be caused by other reasons that need to be further explored in more detail.

Discussion

Although the entire programs for each grade and cycle, manuals, guidelines, and materials have been professionally developed, there is a very serious issue concerning the actual implementation of the program. The administrative issues, misconceptions and the sense of rejection reported in this study result in the detriment of a successful implementation of the NEPBE.

In regards to the administrative issues, payment and working conditions, it is necessary that local and national authorities take actions to provide as much as possible the proper elements for NEPBE teachers to bring the program into the actual classrooms. It is also necessary to find alternatives to provide specialization and training in the TEYL area since, historically, EFL had only been taught in the secondary level and there is not a Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) University or Normal (teacher training) school B.A. programs that respond to the need to form EFL teachers for primary education

In relation to the misconceptions and the sense of reluctance to integrate the NEPBE, the models of the implementation aforementioned suggest the dissemination of the information about the grounds, purpose and expectations of implementation. In this case, it is suggested that national and state coordinators, NEPBE teachers, head teachers, school administrators, and parents be informed about the multiplicity of factors that can positively and negatively affect the success of the program at a national and local levels in order to facilitate the process and diminish the tension among parents, teachers, principals, and the community in general. Although these elements might not seem relevant, as they are not intrinsically academic, numerous resources, time, and energy could be lost as a result of non-academic administrative issues and misconceptions about the program.

The present research sheds light into the possible constraints for the implementation of the NEPBE in the state of Puebla but further research is needed in order to include a broader population and other participants, i.e. parents and those in charge of the evaluation of the NEPBE in the state. It is also necessary to corroborate whether other NEPBE teachers share the views of those that were interviewed or if they are just isolated cases.

Finally, despite the fact that the present research brings to light the areas for growth in terms of the implementation of the NEPBE, it is worth mentioning that we are aware of the fact that considerable progress has been attained in the inclusion of English in basic education not only in the state of Puebla but at a national level. The efforts of authorities and teachers is acknowledged and encouraged in order to make this endeavor more successful in the near future.

References

Armstrong, P. W., & Rogers, J.D. (1997). Basic skills revisited: The effects of foreign language instruction on Reading, Math and Language Arts. Learning Languages, 2 (3), 20-31.

Arthur, S., & Nazroo, J. (2003). Designing fieldwork strategies and Materials. In J. Ritchie, & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social sciences students and researchers (pp. 109-137). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Christensen, S. L., & Cleary, M. (1990). Consultation and the parent-education partnership: A perspective. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 1, 219-241.

Clark, J. L. (1987). Curriculum renewal in school foreign language learning. New York: Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Curtain, H. A., & Dahlberg, C. (2000).Planning for success: Common pitfalls in the planning of early foreign language programs. Washington, D.C.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.EDO-FL-00-11). Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/0011planning.html

De Lano, L., Riley, L., & Crookers, G. (1994). The meaning of innovation for ESL Teachers. System 22 (4), 487–496.

Dey, I. (1993).Qualitative data analysis: A user-friendly guide for social scientist. New York: Routledge.

Fennell, B. A. (2001). A history of English; A sociolinguistic approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

Flege, J. (1999). Age of learning and second language speech. In D. Birdsong (Ed.), Second language acquisition and the critical period hypothesis (pp. 101–131). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gilzow, D.F. (2002). Model early foreign language programs: Key elements. Washington, D.C.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.EDO-FL-02-11). Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/0211gilzow.html

Hancock, B. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research. Downloaded from: Researchfaculty.uccb.ns.ca/pmacintyre/course_pages/MBA603/MBA603_files/IntroQualitativeResearch.pdf. February, 27th, 2007.

Hara, S. R., & Burke, D. J. (1998). Parent Involvement: The Key to Improved Student Achievement. School Community Journal, 8 (2), 219 – 228.

Harley, B. (1986). Age in second language acquisition. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Harley, B., & Wang, W. (1997). The critical period hypothesis: Where are we now? In A. M. B. de Groot & J. F. Kroll (Eds.) Tutorials in bilingualism: Psycholinguistic perspectives (pp. 26–31).Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Krashen, S. D., Long, M. A., & Scarcella, R. C. (1979). Age, rate and eventual attainment in second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 13, 573–82.

Krzyzanowski, M. (2008). Analyzing Focus Groups Discussion. In M. Krzyzanowski, & R. Wodak, (Eds.). Qualitative Discourse Analysis in the Social Sciences (pp. 162- 181). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Loucks, H. (1992). Increasing parent/family involvement: Ten ideas that work. NASSP Bulletin, 76 (543), 19-23.

Markee, N. (1992). The diffusion of innovation in language teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 13, 229–243.

Markee, N. (1997). Managing curricular innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (1999). Does younger = better? TESOL Matters, 9 (3), 1-3. Retrieved from http://davidnunan.com/presMess_99Vol9No3.html.

Pinter, A. (2006). Policy: Primary ELT programmes. In Teaching young language learners (pp. 35 - 44). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plan Nacional de desarrollo 2001-2006. Retrieved May 2008 from: http://www.economia.gob.mx/pics/p/p1376/PLAN1.pdf.

Ramírez, R. J. L., Pimplón, I. E. N. & Cota, G. S (2012). Problemática de la enseñanza del inglés en las primarias públicas de México: una primera lectura cualitativa. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación. 60 (2), 1- 12. Retrieved from http://www.rieoei.org/deloslectores/5020Ramírez.pdf.

Read, C. (1998). The challenge of teaching children. English Teaching Professional, 8-10.

Richards, L. (2005). Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th edn.). New York: Free Press.

Scovel, T. (1988). A time to speak: A psycholinguistic inquiry into the critical period for human speech. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2009). Módulo 1. Elementos básicos. Reforma Integral de la Educación Básica 2009. México: SEP

Shin, J. K. (2006). Ten helpful ideas for teaching English to young learners. English Teaching Forum, 2.p. 2-7, 13. Retrieved from http://exchanges.state.gov/englishteaching/forum/archives/docs/06-44-2-b.pdf.

Waters, A. & M. L. C. Vilches (2008). Factors affecting ELT reforms: The case of the Philippines Basic Education Curriculum. RELC Journal 39 (1), 5–24.

Waters, A. & Vilches, M. (2001). Implementing ELT Innovations: A Needs Analysis Framework. ELT Journal, 55 (2), 133-144

Waters, A. (2009). Managing innovation in English language education. Language Teaching Journal. 42 (4), 421–458. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://aladinrc.wrlc.org/bitstream/handle/1961/3457/gurt_2001_12.pdf?sequence=14.