Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to address some of the strategies for teaching listening comprehension in EFL/ESL classrooms. In addition, I also address some of the factors that can affect the process of teaching listening comprehension. Some students assume that they can understand everything they listen to, and even more, they believe that they are ready to take some university entry exams created for English language learners such as: Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), the Michigan English Language Assessment Battery (MELAB), the Cambridge English Proficiency (CPE), and other language proficiency tests that are required for admission to a college or university in the US, Canada, UK and countries where English is not spoken as a first language. However, many of these students, fail the listening component of the test, and realize that they are not ready to be tested in listening. As a result, they have to cope with a high level of anxiety, which can lead to frustration. Taking these factors into account, the English instructors should be ready to equip these learners, so that the learners can be successful in those tests. However, listening is not about getting ready for a test. The language instructor should be updated with the current methodologies and approaches for teaching listening comprehension, so he or she can foster and equip the learners with the necessary tools to be prepared for all life situations. After all, each course has a different purpose, and each school follows a different approach or program to teach the target language. The following are some strategies that English instructors can implement to foster good listening comprehension among learners.

Frontloading Can Significantly Improve the Listening Comprehension

When EFL/ESL teachers introduce dialogues in the classrooms, the learners will listen to them. However, teachers cannot assume that the learners will grasp the main ideas, nor expect that all learners will grasp all the details spoken in the dialogues. Based on this reality, Mendelsohn (1994) recommends that the teacher must introduce a frontload activity before the students listen to the dialogues. English language learners encounter many challenges when faced with new and unfamiliar words. Frontloading means to activate students’ background knowledge, so they can make connections with the material that will be introduced. This activity can be introduced by a list of vocabulary and speaking about the theme they will listen to. The teacher must make connections from the known to the new, so that the students can have a clue of what they will be listening for.

In addition, it is also recommended to use pictures, real objects or videos to support the listening. By doing this, learners can see the people’s facial expressions and connect those expressions of the speaker and relate them to their experiences. If the students are at a basic level, the use of realia is useful for the learners to connect what they listen to with the conversation and at the same time, the lesson will become more fun for them. A clear example can be in a lesson that deals with money. In this case, the teacher may use real coins and bills, so the language learners can learn the names of currencies in the target language. Another sample of real objects that can be used to teach locations is using real city maps. This will benefit the learners in developing skills in asking and giving addresses, and learn to follow directions by using maps (Mendelsohn, 1994).

The Purpose of Listening

Evidence shows that when people listen to a recording, whether it is an announcement, a report, or a piece of news, they have a purpose in mind. In this case, they want to know about something, such as: a winning number, a plane cancelation at the airport, an alert or something in particular. In the EFL/ESL classroom, the learners will listen to facts, important details, main ideas, etc. The learners do not need to record every word that is said, but they should listen for the gist and main ideas. According to Ur (2016), it is very useful to ask a number of questions before and after the listening activity. These questions will help learners to build background knowledge before they listen, and allow the teacher to assess their comprehension at the end. This strategy can be implemented when teaching phone conversations; for example, learners can be asked to jot down the numbers they hear, and other relevant information they hear from the speakers such as addresses, main ideas, and other details. If the level of the group is too low, then the listening activity can be divided into segments.

The Importance of Teaching Authentic Listening

EFL/ESL learners must be exposed to real life situations, and introduced to different types of listening. One of the strategies used in many language classrooms is having the learners listen to short stories and giving them sets of questions to respond to after they listen. However, this is far from the way listening occurs in real life. This strategy has been around for a long time, and is still being used in many schools today. The fact is that learners find real life listening more motivating and engaging (Ur, 1984). In real life listening, there is an interaction between the speaker and the listener who interact through questions and answers. In real life, if the listener does not understand the message, he or she can ask for clarifications. According to Ur (1984), when teaching listening comprehension, language teachers should not leave all the questions for the end, but should also ask questions at the beginning, middle and at the end of the listening. This will foster the interaction in the classroom, and will give the teacher a better chance to check the learners’ understanding.

Likewise, in many cases, listening in real-life situations differs from the type of listening introduced in the classroom. Can one assume that language classroom speech reflects the language of the real world? If one listens to people speaking in the city of New York where there are many accents of English, then one cannot expect that second language learners will be able to understand each and every speaker they listen to. Students usually have trouble understanding people outside the classroom (Paulston & Bruder, 1976; Porter & Roberts, 1981; Rings, 1986; Robinett, 1978). But the trouble becomes harder when they are exposed to different dialects of the same language, such as those spoken in New York, Toronto, Philadelphia, and other metropolitan cities where English has become a melting pot of different cultures speaking the language with different accents. However, in many cases, students do not receive the necessary training to understand the language spoken by people who do not speak the type of English they listen to in the classroom, since they are always told that the English they learn in class is “Standard American English”. But the question is: who speaks standard American English? And are English language learners supposed to be trained to listen to only this type of English? Therefore, taking into consideration that English is not the language of textbooks, it is recommended to expose English language learners to different types of listening. Adkins and Eykyn (1989) suggest that teachers examine current practices and materials used in language classes, so that language teachers can decide what students should be listening to and allow the learners to have the necessary exposure to natural and authentic language. A very good video series available on line, which can be very good to expose English language learners to the different types of dialects spoken in the US, is Do You Speak American? hosted by the journalist Robert McNeil. In these videos, one can observe how American English changes all over the US, and at the same time, it will give the English language learners an opportunity to learn about the different accents that exit in North American English. Of course, there are a number of dialects in British English too. It is good for all students to listen to a variety of Englishes.

It is a fact that teachers cannot provide students with authentic listening all the time; however, English language teachers should take into account that there are many characteristics of speech that do not represent real life listening in recordings. In many of these recordings, the intonation of the speakers is very artificial and lacks the natural intonation of real speech (Long & Richards, 1987). In some of the recordings that are implemented to teach the target language, one can find that the intonation used does not even match the context or the situation in which it is applied. Another characteristic that one can observe in English is enunciation; for example, in the words when /wuen/, and why /wuai/. In this case, the /h/ is not pronounced because it is assimilated. Furthermore, one can find a similar example in phrases like “last year” and “it must be” where the /t/ is not pronounced. Of course, this linguistic phenomenon is applied in colloquial English. Other examples can be observed in “expected to” where the /d/ is elided and in “wet ground”, the /t/ is elided. These language phenomena that occur in real life speech are the patterns that should be implemented in listening comprehension courses, so that English language learners can develop their listening skills to be able to understand native speakers of English. This sound omission can also occur in many other sounds of English, such as in “I think so” where the /k/ is omitted. As a result, the teacher should look for textbooks and videos that have these linguistic features (Brown, 1999).

Other factors that must be taken into account when teaching listening comprehension are the pace and rhythm of the speech. In real life, the pace of a conversation changes according to the situation or the context where the language is being used. If two speakers are in a hurry while exchanging information, the speed and rhythm of the conversation will be faster than when they are in a cafe or a more relaxed place. Therefore, it is also recommended that the texts used for teaching listening comprehension include these features of the language. Ironically, in some texts, such as the New Interchange by Richards, one can see that the pace and rhythm in some of the conversations is boring. On the other hand, if one watches the videos available on http: //www.esl-lab.com, created by Davis, one will notice the difference in the speech patterns used in Interchange and the Videos at ESL-Lab.com. Therefore, it is also recommendable to use these videos in class to teach listening comprehension, since the learners will benefit much more than just limiting them to the textbooks.

Factors that Cause Poor Listening Comprehension for Learners

According to Avery and Ehrlich (2002), some factors that cause poor listening comprehension are the lack of the leaner’s linguistic competence. For example, when a learner confuses the sounds in English, he or she might confuse words such as ship and sheep, pen and pin, reach and rich, and hut, hot and hat. Hence, it is paramount to teach English phonetics to English language learners, so they become familiar with its sound system. Often, these sounds are absent in the learners’ first language, so this makes it harder for them to comprehend unfamiliar sounds in the target language.

Another relevant strategy that must be applied is the teaching of linking sounds in English. According to linguists Avery and Ehrlich (2002), many English language learners may think that they are listening to a single word, since most native speakers of English connect the words forming linking sounds. Clear examples of these linking sounds are: not at all, put it up, and put it down. The advantage of teaching linking sounds is that it not only develops better listening comprehension, but it also helps language learners to develop fluency in the target language.

Teaching Vowels and Word Stress Can Help Improve Listening Comprehension

Instead of the five vowel sounds that Spanish, Italian, French, and Portuguese have, English has eleven vowel sounds (Prator & Wallace, 1985). English also has a vowel sound that does not exist in other languages; this is the reduced vowel sound called schwa, which is the most common vowel sound in spoken English. The following are examples of words in which this sound occurs /ÊŒ/as in hut, cut, gun, and /É™/ as in about, admire, around, again, system, etc. (Every & Ehrlich, 2002). In addition to these vowel sounds, there are also a number of consonants that are absent in some other languages, but are part of English, and this is another factor that causes poor listening comprehension for students. Some of these consonant sounds that affect the listening comprehension of non-native English speakers are: /dÊ’/ as in procedure, judge, edge; /tʃ/ as in butcher, kitchen, furniture; /θ/ as in Ethiopia, ethnic, worth; and the sound /ð/ as in although, within, without, farther, etc. Consequently, it is relevant to teach learners these sounds and many other relevant sounds that will help them to improve their listening comprehension. Therefore, teaching the English sounds in an explicit way will help learners to understand English better, and avoid confusion of words when listening to these sounds.

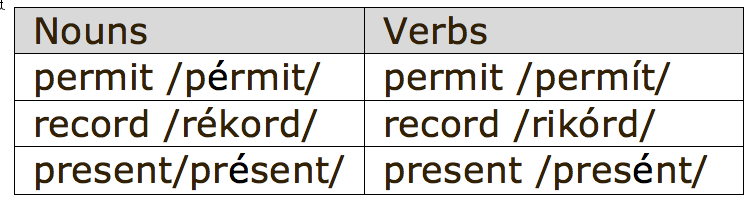

Another relevant aspect that must be considered when teaching listening is the word stress in the English language. In English, words stress is different from other languages. Some words in English keep the same spelling when they change from nouns to verbs. As a result, the same words can serve as a noun or as a verb. The following is a list of such case:

This linguistic phenomenon of shifting stress in the English language does not occur in Romance languages, since the written structure of the word changes when it is used in other tenses.

Dictation Helps to Improve Listening Comprehension

To many language teachers, it may appear that dictation is limited to testing spelling and, perhaps, word recognition; however, according to Oller, (1971), it is reasonable to assume that listening comprehension can also be assessed when teachers do dictations in class. Furthermore, contrary to some other languages, in English there is a difference between the graphemes and phonemes of the words. As a result, this difference tends to confuse learners. Many language teachers avoid dictation in class, ignoring the benefit that it can bring to the learner. Dictation is a good strategy to assess the learners’ skills not only in spelling, but also in listening to foreign sounds. When teachers use dictations in the classrooms, the learners cannot rely on any visual aid; therefore, they have to make a bigger effort to understand. In addition, this activity can help learners to develop note-taking for college and university students. According to Mendelsohn (1994), teaching listening comprehension does not mean testing learners, but helping them develop listening comprehension, so they can understand the language. However, it is also a fact that dictation can help to assess the learners’ skills in comprehending some sounds of English.

Furthermore, the EFL/ESL teacher should also be aware of the pitch, volume, rate, and speed that he or she uses to carry out the dictation. It is recommended that the speed the teacher uses should vary according to the level of the group. The speed that the teacher will use in an advanced group cannot be the same he or she uses for a beginner group. Moreover, the dictation must be done as naturally as possible, since there are many teachers who exaggerate their pronunciation in such a way that it is too far from the way real speech occurs. The teacher can read a text aloud, or he or she can bring some recordings that fit the group level. A very good book for insights on dictation is Pronunciation Plus by Hewings and Goldstein (2001).

Conclusion

In this paper I have attempted to explain the importance of listening comprehension combined with the teaching of pronunciation. It is important to remember that when teaching listening comprehension, one should use authentic materials, such as news, recorded lectures, videos, and other sources from real life. In fact, this is the kind of exposure that language learners need. I do encourage language teachers to implement the techniques that I have mentioned, and to read more on the references that I have included in the paper, so they can expand their knowledge of teaching listening to language learners. Therefore, any language teacher who really wants to see his or her learners’ progress should implement the above strategies for teaching listening, strategies that will enhance the comprehension of the target language, and it will make the learning process less boring.

References

Avery, P., & Erlich, S. (2002). Teaching American English pronunciation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, G. (1999). Listening to spoken English. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Davis, R. (1998). Randall’s ESL cyber listening lab. Retrieved from http://www.esl-lab.com.

Hewings, M., & Goldstein, S. (2001). Pronunciation Plus. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Long, M.H., & Richards, J C. (1987). Methodology in TESOL.New York. Newbury House.

McNeal, R. (2014, April 6). Do you speak American? (Video File). Retrieved from http://www.youtoube.com.

Mendelsohn, D. (1994). Learning to listen. San Diego: Dominique Press.

Mendelsohn, D. (1995). A guide to teaching second language listening. San Diego: Dominique Press.

Mendelsohn, D. & Rubin, J. (1997). A guide for the teaching of second language listening. San Diego: Dominie Press.

Paulston, C. B. & Bruder, M. N. (1976). Teaching English as a second language: Techniques and procedures. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop.

Prator, H. & Wallace, B. (1985). Manual of American English pronunciation. Orlando: Holt Rinehart & Winston, Inc.

Oller Jr., J. W. (1971). Dictation as a device for testing foreign-language proficiency. ELT Journal, 25(3), 254-259.

Richards, J.C. (1983). Listening comprehension: Approach, design, procedure. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 2, 219-240.

Richards, J. C. (2008). Teaching listening and speaking from theory to practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Robinett, B. W. (1978). Teaching English to speakers of other languages: Substance and technique. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ur, P. (1984). Teaching listening comprehension. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ur, P. (2016). 100 teaching tips. Cambridge handbooks for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.