Introduction

Listening is a complicated process that requires receivers to “comprehend the text as they listen to it, retain information in memory, integrate it with what follows and continually adjust their understanding of what they hear in the light of prior knowledge and incoming information” (Osada, 2004, p. 60).

Studies have focused on developing listening skills through both intensive and extensive listening (e.g., Chang & Read, 2006; Jones, 2008; Renandya, 2011). However, “real-life listening is interactive” (Holden, 2008, p. 301) and might require more than just “comprehensible input” (Krashen, 1985). This paper, therefore, has taken a different approach in that listening comprehension might be developed through interaction where learners work in groups to actively search, share, discuss, and report.

The current study aims to examine whether active learning group discussion activities help develop lower-level students’ listening comprehension skills. Accordingly, the research question is: To what extent do active learning group discussion activities help develop lower-level learners’ listening comprehension skills?

Literature Review

Listening has been called a “Cinderella skill” (Nunan, 1997); in other words, it is a passive skill that should be developed by itself despite it representing at least 40% of our daily communication (Flowerdew and Miller, 2005; Walker, 2014). It was not until 1970 that listening comprehension was considered a discrete language skill (Osada, 2004; Walker, 2014). This very late consideration made listening (i) the “least researched of all four language skills” (Vandergrift, 2007, p. 53); and (ii) it has receive less attention in academic courses compared with grammar, reading, and vocabulary skills (Hamouda, 2013).

Developing Listening Skills

To understand written and verbal input, learners usually use “bottom-up” and “top-down” processes. “Bottom-up processes call on the student’s previously learned knowledge with reference to lexical awareness and knowledge of grammatical and syntactical aspects of the language, whereas top-down processes draw upon the student’s ability to utilize background knowledge that has been gathered and stored from previous experiences to decipher meaning” (Walker, 2014, p. 169). Both processes are used in teaching/learning listening skills. The bottom-up listening process, as explained by Morley (2007), is when attention is given to every single detail regardless of personal experience and knowledge. Morley (2007), offered an example of the bottom-up listening process as when listening to a friend giving an address. Bottom-up listening skills are now the main focus of the EFL listening materials.

On the other hand, for the top-down listening process, attention is not given to every simple detail, but rather to the main topic and how it matches with listeners’ experience and personal knowledge. Morley (2007) introduced an example of the top-down listening process as when listening to a friend talking about their recent unpleasant holiday, and how this might be followed with some sympathy or surprise reactions without fully understanding all the details. Second/foreign language learners, even advanced ones, use this listening process when coming into contact with unfamiliar words or difficult structures (Morley, 2007).

A fluent EFL listener should use both top-down and bottom-up listening learning processes (Morley, 2007; Walker, 2014). For these two processes to be successfully implemented in class, group discussion activities might be needed. Students should work in groups to listen to each other, clarify the meaning with follow-up questions, and respond with reactions. Such group work and discussion processes are among the most important core features in any active learning class; i.e., no active learning takes place without discussion and group/pair work (Hackathorn et al., 2011).

Group Work Activities

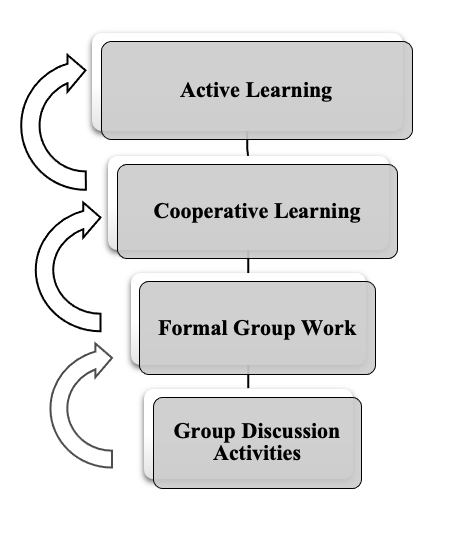

Group work activities in active learning are called “cooperative learning” (Faust & Paulson, 1998). Cooperative learning is a structured process to achieve certain goals (Cooper & Mueck, 1990; Faust & Paulson, 1998), and can be classified into three types: informal cooperative is when teachers quickly assign students into groups to discuss a specific term, share the experience of a certain issue, or even to share their notes during a lecture (Giddon & Kurfiss, 1990). Formal cooperative is when the task requires more time, often with a report to submit (Sharan & Sharan, 1994). Teachers can also set the groups based on certain criteria like interest, gender, or even academic performance. Students should work together to achieve certain goals, with the teacher monitoring their progress (Cooper et al., 1990; Faust & Paulson, 1998; Smith, 1996). Clearly, this type requires more preparation and work from teachers to achieve. Teachers should also have clear goals that should fit with their students’ academic and professional skills. The base group (Slavin, 1994) is when teachers aim to establish long-term projects or relations among students. A base group can last for a full academic term and can replace or work with informal and formal cooperative types (Faust & Paulson, 1998).

To summarize and as shown in Figure 1, the implemented intervention (group discussion activities) represents formal group work, with goals, a certain time frame, and a final required report. The formal group is one of the cooperative learning types that strongly represents active learning.

Figure 1: Intervention: Group discussion activities

The Intervention

Fifteen active learning group discussion activities have been created based on insights from Elmetaher’s (2021) Active Learning Checklist. In this article, Elmetaher argued that any active learning activity should (i) start with the main goals, ideas, and concepts; (ii) boost students’ motivation, questions, and interests with lots of authentic life situations and materials; (iii) include a variety of resources with references; (iv) handle learning as flexible, changeable, buildable knowledge, rather than solid, unbroken sets of facts; and (v) implement different assessment tools to measure students’ efforts in class more than through their memorizing capabilities, using such tools as portfolios, observations, interviews, peer-assessments, self-assessments, etc., with lots of feedback.

Each group discussion activity addressed a debatable question as its main goal, for example, Should violent video games be banned? On an individual basis, students first search for and actively listen to online English audio or videos with no subtitles to answer the class question. Students are encouraged to take notes as they listen. They can also repeat the same audio/video several times if they wish. They are then divided into small groups of 3–5 students to discuss and share what they have found. Finally, one or two students are randomly selected from each group to answer the class question. The quality of their answers should reflect the amount of effort, sharing, and discussion of each group, which teachers can later convert to points as a means of assessment. A short debate between the groups’ answers, if different, might also work well, especially with advanced students.

Study Procedures

The study was administrated in three main steps. First, a pre-listening test, adapted from the What a World: Listening 1textbook (Broukal, 2011), was created and administered at baseline. Second, fifteen active learning group discussion activities were developed and implemented in a computer lab for a full academic term (15 classes, one class per week, 90 minutes each). Finally, a parallel post-listening test was created and administered after four months to measure the students’ listening comprehension skills progress. Both versions of the listening test (See Appendix) were equivalent in terms of difficulty, number and types of questions, the possible score for each question, and time provided. Each test lasted for 45 minutes and contained multiple choice, true/false, and comprehension questions. Students were allowed to listen to the test audio only once.

Participants

The study included 25 (10 male, 15 female) second language (L2) undergraduate learners (of English) from a university in western Japan, all with Japanese as the L1. All participants were enrolled in a compulsory academic English listening class in their first year at university and were all aged 18 years. All participants had received approximately three hours of English language tuition weekly from the age of 13 to the moment this study was done. Participation in the study was voluntary with the right to opt out at any time. Participants provided written informed consent. Personal data were protected as mainly the average mean test scores were reported in the study results, with no personal information of any of the participants. The XY_Lex (Meara & Miralpeix, 2016)[1] computerized receptive vocabulary task was administered at the first class to estimate participants’ proficiency level. The XY_Lex indicates a vocabulary size range of 1,750–4,800 words (M = 3,160, SD = 873) out of the maxmuim possible score of 10,000, indicating a beginner to the pre-intermediate level of English proficiency.

Results

Q. To what extent do active learning group discussion activities help develop lower-level learners’ listening comprehension skills?

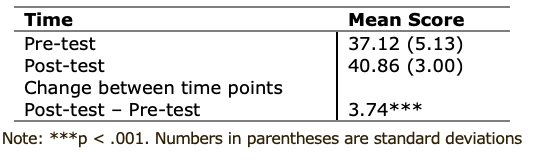

Table 1 shows the listening test mean scores at the pre-and post-tests. There is a significant difference in the listening test scores (3.74) for the pre-test (M = 37.12, SD = 5.13) and the post-test (M = 40.86, SD = 3.00), (t (24) = −3.648, p < .001).

Note: ***p < .001. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations

Table 1. Listening test scores at pre-test and post-test

Discussion

Referring to the significant score increase over the four-month listening course with an intervention of active learning group discussion activities, it might be suggested that developing passive English skills (i.e., listening) can happen through interaction, where learners discuss and negotiate, and not solely through intensive input. When students discuss and share, not only does language develop, but their motivation, engagement, attentivity, and energy are also developed (Hackathorn et al., 2011; Ryan & Patrick, 2001).

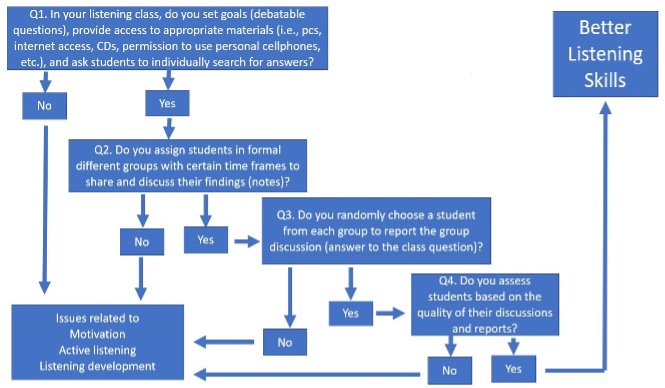

As a teaching implication, the study suggests a 4Q (Four Questions) teaching strategy for listening courses as listed below. The 4Q teaching strategy has the potential to be implemented with different language skills.

The 4Q Teaching Strategy

The 4Q (Figure 2) refers to four main questions that teachers might address to ensure successful implementation of the study intervention in their listening classes. The four questions represent a short version of the study intervention.

Q1. In your listening class, do you set goals (debatable questions), provide access to appropriate materials (i.e., pcs, internet access, CDs, permission to use personal cellphones, etc.), and ask students to individually search for answers?

Q2. Do you assign students in formal different groups with certain time frames to share and discuss their findings (notes)?

Q3. Do you randomly choose a student from each group to report the group discussion (answer to the class question)?

Q4. Do you assess students based on the quality of their discussions and reports?

Answering “yes” to all the four questions might indicate a successful implementation of the study intervention, better expectations of the students listening scores, and a reduction in issues related to motivation and active listening. For visual interpretation, the 4Q teaching strategy has been mapped below.

Figure 2. 4Q teaching strategy

Conclusion

The current study aimed to examine whether active learning group discussion activities can help develop lower-level students’ English listening skills. The results of this limited study indicate a significant increase in participants’ listening scores. Such a significant increase (i) seems to support the view that teaching passive English skills (i.e., listening) can be done through interaction, and not solely through intensive or extensive input; and (ii) can support the language listening curricula by adding the study intervention of active learning group discussion activities as possible significant content. The study intervention was introduced through an easy-to-follow 4Q teaching strategy. The 4Q teaching strategy has the potential to be implemented with different populations, language levels, and with reading as the other passive language skill.

References

Broukal, M. (2011). What a World Listening 1: Amazing Stories from Around the Globe. Pearson Education.

Chang, A.-S. C., & Read, J. (2006). The effects of listening support on the listening performance of EFL learners. TESOL Quarterly, 40(2), 375-397. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264527

Cooper, J., & Mueck, R. (1990). Student involvement in learning: Cooperative learning and college instruction. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 1(1), 68-76.

Cooper, J., Prescott, J. S., Cook, L., Smith, L., Mueck, R., & Cuseo, J. (1990). Cooperative learning and college instructions: Effective use of the student learning teams. The California State University Foundation.

Ellis, R. (1997). Second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

Elmetaher, H. (2021). Active learning in language classrooms: From theory to practice. In ACADEMIA-Literature and Language (pp. 309-316). Nanzan University Press.

Faust, J. L., & Paulson, D. R. (1998). Active learning in the college classroom. Journal of Excellence in College Teaching, 9(2), 3-24.

Flowerdew, J., & Miller, L. (2005). Second language listening: Theory and practice. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667244

Gliddon, J., & Kurfiss, J. G. (1990). Small-group discussion in Philosophy 101. College Teaching, 38(1), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.1990.10532176

Hackathorn, J., Solomon, E. D., Blankmeyer, K. L., Tennial, E. R., & Garczynski, M. A. (2011). Learning by doing: An empirical study of active teaching techniques. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 11(2), 40-54.

Hamouda, A. (2013). An investigation of listening comprehension problems encountered by Saudi students in the EL listening classroom.International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 2(2), 113-155.

Holden, W. R., III (2008). Extensive listening: A new approach to an old problem. Bulletin of Faculty of Humanities, University of Toyama, 299-312.

Jones, D. (2008). Is there any room for listening? The necessity of teaching listening skills in ESL/EFL classrooms. https://www.kansai-u.ac.jp/fl/publication/pdf_forum/7/02_jones_15.pdf

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Laredo.

Meara, P., & Miralpeix, I. (2016). Tools for researching vocabulary. Multilingual Matters.

Morley, C. (2007). Listening: Top down and bottom up. TeachingEnglish. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/listening-top-down-bottom

Nunan, D. (1997). Listening in language learning: The language teacher. The Japan Association of Language Learning, 21(9), 47 - 51.

Osada, N. (2004). Listening comprehension research: A brief review of the last thirty years. 2004 TALK Japan.

Renandya, W. A. (2011). Extensive listening in the second language classroom. In H. P. Widodo & A. Cirocki (Eds.), Innovation and creativity in ELT methodology. (pp. 15-28). Nova Science.

Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents' motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437-460. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038002437

Sharan, Y., & Sharan, S. (1994). Group investigation in the cooperative classroom. In S. Sharan (Ed.), Handbook of cooperative learning methods (pp. 97-114). Greenwood Press.

Slavin, K. W. (1994). Student teams-achievement divisions. In S. Sharan (Ed.), Handbook of cooperative learning methods (pp. 3-19). Greenwood Press.

Smith, K. A. (1996). Cooperative learning: Making "groupwork" work. In T. E. Southerland & C.C. Bonwell (Eds.), Using active learning in college classes: A range of options for faculty. (pp. 71-82). Jossey-Bass.

Vandergrift, L. (2004). Listening to learn or learning to listen? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190504000017

Vandergrift, L. (2007). Recent development in second language listening comprehension research. In G. Porte. (Ed.), Language teaching: Surveys and studies (pp. 291-210). Cambridge University Press.

Walker, N. (2014). Listening: The most difficult skill to teach. Encuentro, 23, 167-175. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/58911108.pdf

[1] XY_Lex requires participants to respond to a Yes/No computerized task in which 120 words are presented. The 120 words represent the 1,000–5,000 and 6,000-10,000 word frequency bands.