Changes in technology have led to a re-examination of the concept of literacy. The dynamic changes in literacy practices using technology have also called for a new way to approach literacy instruction. Thus, the purpose of this article is to provide a synopsis of a new literacy practice, that of texting, and present what research teaches us about how to effectively incorporate this literacy into our language classrooms. The article ends with pedagogical suggestions.

Brief History of Texting

The language that people commonly use when sending text messages, instant messages, or simply when writing on a website has been called “digital language” (Crystal, 2008b) or “textese” (Crystal, 2008a), among other terms. Textese is characterized by its short length, multimodality (a combination of alphanumeric characters, images, symbols, and sometimes sounds), usage of punctuation characters to represent facial expressions, and its tendency to abbreviate words and phrases. Although this way of using language developed to save time and space, individuals now use it to express identity, represent language varieties, and foster creativity through linguistic play (Crystal, 2008b; Grace, Kemp, Martin, & Parrila, 2014). Despite these advantages, Crystal (2008b) explains that some still consider textese wrong, ungrammatical, and inappropriate.

The main reason for such criticisms is that textese does not follow the grammatical conventions of academic literacy. It deviates from the standard written morphosyntactic conventions taught in school to be the only correct form. That said, textese utilizes morphosyntactic and etiquette conventions much like spoken language conventions, which are at once individual to the mode itself and also influenced by external communicative systems. Cultivated knowledge of text conventions is linked to gains that are twofold: 1) development of awareness of orthographic principles of representation and a deeper appreciation for form or structure, and 2) development of awareness of communicative norms in multiple digital spaces, which enables increased complexity (i.e., attachments, code-switching, instant contextual clues, etc.) of communication and can assist in academic performance and socialization.

Achieving academic excellence is an isolated task and it is often competitive. It also includes complex assignments and requires the need to collaborate outside the classroom. The completion of collaborative assignments is what leads students to form out-of-the-classroom networks. Students increasingly rely upon technology to form these networks, and what is more, to navigate them. The complexity of these networks is explored in Zappa-Hollman and Duff (2015) wherein, upon reviewing university exchange student data to see how students who thrived differed in social support, the authors realized they were missing almost all of the face-to-face collaborative process. Negotiation was not present in student emails—all their required schoolwork was processed through their text and Short Message Service (SMS) accounts using textese. While younger students may have unregulated access to phones, or even no access at all, in-class teacher-guided, authentic task cooperation can foster confidence, competence, and self-aware selection of digital spaces for academic attainment. Therefore, as a newer literacy practice, integrating the teaching of texting language, or textese, into curricula would serve not only to teach students about language but also how to be competent and critical users of the language needed to engage in digital literacy and academic socialization.

Evolution of Language Use in Texting Practices

The language used in digital contexts did not develop out of an intrinsic desire to break rules, laziness, ignorance, or bad habits. When SMS first appeared over 20 years ago, it had to be transmitted over mobile phones. Messages were constrained by a 160-character limit, the use of a numerical keypad to write, and high fees associated with every word sent. These constraints drove users to abbreviate words and expressions, such as “c u l8r” (see you later) and “ROFL” (rolling on floor laughing). Users did not employ punctuation marks as they paid more attention to the meaning rather than the form of the message in an attempt to become efficient. This deviation from academic conventions and style is what causes some people to view texting language as ungrammatical, telegraphic, informal, and a mere representation of oral language into writing.

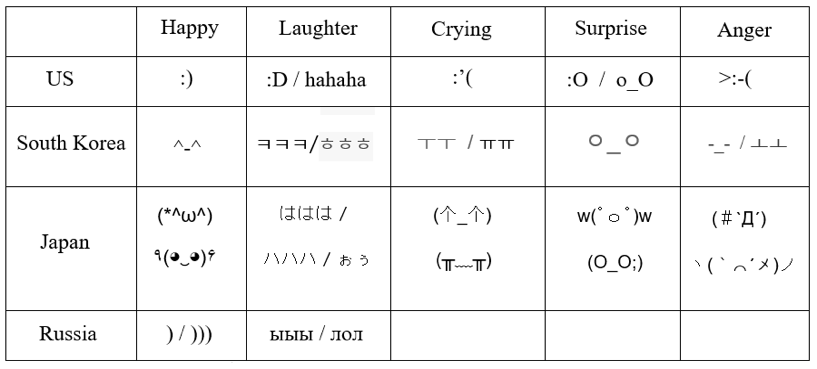

Critics of this type of writing (i.e., texting) presume writing itself has always been static. However, as users’ representational needs became more diverse, multimodal ways to convey meanings in texts increased (Bezemer & Kress, 2008). Bezemer and Kress explain that in the last five decades, layout, syntax, and the ways that images interact with text have become diverged further from standard language to better convey meaning. For example, Figure 1 shows the complexities inherent in the different communication patterns from different countries, as seen in the Japanese text representations. A great deal of information is communicated within Japanese emoticons including the speaker's gender and mood. For example, omega mouths are favoured by female speakers. This omega figure is similar to the South Korean “middle finger” emoticon signified by the Hangul /O/ vowel. These types of offensive emoticons may be deeply offensive, restricted and even illegal to send in certain contexts. Russian faces follow international trends, not surprising due to keyboard limitations.

Figure 1. Representation of Complexity in SMS.

The evolution of text practices is displayed through the change of text length and the birth of new emoji, and embodied in its transformation, texting practices also represent identities and social contexts. Nowadays, texting is no longer a simple reduction of words and phrases used exclusively by youth. Instead, these reductions are stylistic choices that represent social identities and gender (Ling, Baron, Lenhart, & Campbell, 2014). They are also phonemic representations of users’ dialects (Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith, & Xing, 2010), which are used to showcase ethnic identities and social affiliations (Johnstone, 2013). For example, Eisenstein et al. (2010) found that Twitter users in northern and southern California abbreviate the word “cool” as “koo” and “coo” respectively, and some Twitter users abbreviate something as “sumthin,” but around New York City the word is abbreviated as “suttin.”

The use of emotion-based icons (emoticons) also varies depending on cultural context (e.g., a smiley face can be represented with an icon “J”, with punctuation “: )” in the U.S., but as “^.^” in Japan) as can be seen in Figure 1. However, the size of the Cyrillic alphabet and nature of keyboard layout in Russia have conspired in the evolution of smiley faces, which no longer have eyes due to the complexity of accessing the colon. Overall local and international linguistic subtleties give rise to communicative complexities; these complexities are why texting is a literacy practice in itself.

The rapid increase of web-based technologies has facilitated the evolution of texting practices (see , Kemp & Plester, 2013. People more commonly employ textese in emails, instant messaging, and other texting platforms such as Whatsapp and iMessage. Additionally, in Twitter, a platform that allows only 140 characters, the practice of reducing words and abbreviating sounds is vividly represented. Therefore, the evolution of texting practice is happening not exclusively in SMS, but it is also presented in different mobile platforms.

The fast evolution of texting practice requires children, teens, and adults to learn how to decode and encode texts cross-linguistically, cross-culturally, and even generationally (see Wood, Kemp & Plester, 2013). Particularly in the classroom, learners need to text back and forth about assignments with appropriate respect, understanding, patience, and brevity, to maintain an effective feedback loop with teachers or their peers. At the same time, learners need to be able to competently navigate multimodal communication platforms where texting ideations and linguistic patterns are the norm.

Texting as a Literacy Practice

In the era of digital technologies, competency in reading and writing in the standard variety of a language may no longer be sufficient to communicate in digital environments. The concept of “multiliteracies” has been adopted to expand the traditional notion of literacy in order to account for the linguistic and cultural diversity in a particular society (New London Group, 1996). Multimodal literacy practices encompass not only new orthographic and discourse conventions but also the development of new genres through the collaboration, remixing, and combination of other modes of communication (audio, visual, and gestural) especially with the aid of digital technologies. In this expanded notion of literacy, grammars are reformulated to describe how multimodality (the use of images, sounds, text, and other digital elements) enriches and modifies word meanings. The grammatical innovation and the genres it has created (e.g., textese) are what make the language of texting a type of literacy (Crystal, 2008). Thus, texting should not be placed against academic literacy but as an alternate form of literacy which is paramount (although not exclusively) to digital literacy competency (Hockly, Dudeney, & Pegrum, 2013).

Not including multimodality in teaching literacy as we move forward would mean continuing to ignore the array of converged semiotic resources that individuals already use in meaning-making outside of classrooms (Street, Pahl, & Rowsell, 2014). Further, excluding multimodality would reduce access to the adaptive skills and tools proven to assist university students integrate into their new communities. Further research is needed to see more closely how L2 learners acquire normative academic socialization patterns with their colleagues, or, in contrast, how they might establish identity or agency through resistance to competing local discursive norms.

Prior Research on Texting Practices

Although the use of mobile devices has been normalised (Pegrum, 2014), the belief that texting practices have detrimental consequences for literacy development and for the English language, in general, because it “dumbs down” communication, is widely circulated in popular culture. Consequently, there has been resistance to include texting practices in lesson design. Those resistant to curricular inclusion cite possible interference with orthographic development and recognition of correct spelling. Others, who reject the single-entendre texts translations of classic literature currently available, point to the materials’ stale pictographic representations and waddled down extraction of dialogic elements (Gillman, 2015).

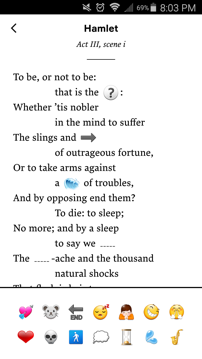

The latter is a valid criticism, as academic material should remain dense and challenging. For example, the differences between the Bard’s classic content and the “YOLO, Romeo” remix are rooted in social norms—downplaying sex and violence, for instance—more than those differences are rooted in inherent limitations in texts variations (see Figure 2). The author is including an example of a text translation of a line from Tom Stoppard’s reimagining of Hamlet, titled Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. Here both a play and an EFL assignment are visible and reflect academic rigor and appropriation for self-expression without diminishing content. Therefore, it is possible to explore and represent more approximately the depth of content Shakespeare proffers when text renderings are made in informal lexical terms in pursuit of higher academic aims (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.Transformation between Emojis and CALP in Game Mode-Switching.

The idea that texting in formal or informal settings will be detrimental to overall spelling capabilities and literacy development is a misunderstanding of how semiotic encoding and decoding practices contribute to metalinguistic strategies in learners and facilitates cross-linguistic processing. In other words, while developing the skills to switch, recognize and express themselves in two competing codes, students become aware of the basis of being socially appropriate and of code-selection.

Empirical research on language use in text practices has yielded inconsistent results (Plester, Wood, & Bell, 2008). Alternatively, some studies on first language (L1) use have demonstrated that exposure to misspelled words can have a negative impact on identifying correct spellings (c.f., Grace et al., 2014; Wood, Kemp & Plester, 2011). These studies, however, have been criticized for utilizing contrived and concurrent data which do not represent the natural texting practices, nor the direction of the association between texting and literacy development (Wood et al., 2011). In contrast, studies demonstrate that if there is, indeed, an effect of texting on literacy, it is not likely to be detrimental (Plester et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2013). These studies have used longitudinal data, children’s actual text messages, and spontaneous texting use to explore both the nature of texting practices and the associations between texting and literacy development. For example, researchers found that students who use more text abbreviations usually perform higher in verbal reasoning ability and spelling tests (Grace et al., 2014; Plester et al., 2008). Studies about adults have also yielded mixed results. However, recent research explains that if there is a negative effect, it is due to personal attitudes regarding the appropriateness of texting practices rather than overall texting use (Grace et al., 2014). There are no similar empirical studies that explain whether the same results are true for second language (L2) users; however, the results of associated literature shed light onto the potential uses of texting in L2 teaching and may raise language awareness accordingly.

In addition to studying the language used in the texting practices, studies were also conducted to evaluate the impact of texting practices in higher education. Experiences of adult university students in a study abroad context shed light on the role of texting in professional success, and support the urgent need to promote academic negotiation, appropriate identity indexing, and social network development through mobile technologies. While observing Mexican exchange students pursuing degrees in a Canadian university setting, Zappa-Hollman and Duff (2015) noted the significant role social support structures played in overall student comfort and success. Most significantly, “study-related” interaction and multiplex (e.g., classmate + friend, or, fellow exchange student + lab partner + roommate) relationships were the most instrumental in 1) socialization and 2) academic success (Zappa-Hollman & Duff, 2015). Therefore, it was blended academic discourse—business and casual—that led to meaningful, grounding interactions. Participants’ journals reflected on perceptions of acceptance, agency, and cultural capital, and led to the desire for a close analysis of the social networking that helped students cope with expat realities. However, as stated above, in that research these exchanges took place via texts, but such texts themselves were not collected nor analysed. Research needs to evolve with communicative patterns by examining the SMS and abbreviated email practices of collegiate learners. Furthermore, to help develop collegiate learners capable of advanced collaborative practices, it is recommended that relationships be developed between “fun” tech and scholastic/social functionality from a young age. Much like ludic-learning language play leads to linguistic and behavioural appropriation of advanced roles. Situated texting practice also raises awareness of the communicative survival strategies that promote persistence and positive outcomes in complex, high-pressure environments.

Text Practicing in the Classroom

With the surge of mobile devices, Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) and teaching texting has become commonplace in foreign language instruction (Burston, 2014). Despite this integration, Burston (2014) argues that studies of MALL implementations conclude a lack of research on the curricular integration of texting, as MALL practice has only included limited experiments and class trials. Because very little research on texting and literacy effects in language learning environments exists, it is important to seize the potential of texting activities to fully integrate them into a curriculum for further study.

The following ideas are the product of pedagogical theorizing and not of empirical research; however, similar ideas have been recommended for classroom use (Hockly et al., 2013) and have been used extensively and successfully by the authors. The ideas are grouped according to the framework of the pedagogy of multiliteracies. The theory of multi-literacies pedagogy was developed, drawing on sociocultural principles of literacy learning.

Multiliteracies pedagogy theory suggests educators should purposefully cultivate critical awareness of multimodal platform communicative norms (see Cope & Kalantzis, 2015). Teachers need to promote the practice of helping students develop the ability of noticing and switching from one style to another. Likewise, teachers can help their students develop the ability to merge their academic needs with their communicative medium’s ability to appropriately affiliate, express, and interpret information. These abilities are all verifiable digital literacies and necessary for social success, academic success, and socio-academic success. Importantly, integrating these ideas into a curriculum is also an opportunity to further the studies of texting and its effects on language learning as texting practices go beyond one time activity to a permanent part of language instruction. The following teaching ideas are to encourage ELT professionals to harness the popularity of texting and teach English in an authentic, fashionable, and already widely used way, while simultaneously helping students develop critical awareness of texting use in digital spaces.

Situated Practice

Situated Practice is the practice of immersing students in heavily contextualized sociocultural settings in specific knowledge domains (New London Group, 1996). Its aim is to engage learners in authentic versions of such practices in order to attain language proficiency and customary behaviours. Under this view, immersion is key and should not be isolated, as situated practice does not necessarily lead to “conscious control and awareness of what one knows and does, which is a core goal of much school-based learning” (New London Group, 1996, p. 84).

Situated practices need to be carried out in a community of learners who can take multiple and different roles based on their backgrounds and experiences; for instance, experts can mentor novices. This is not to be taken as a static relationship, or even the norm in digital practices in all environments. In many ways, novice groups naturally lead to scaffolding among novices. Scaffolding, according to Vygotsky (1978), is the support which is provided by the instructor or peers to learners to facilitate skill development. The assistance would enable learner to complete tasks that were usually unaccomplished independently. For example, an equally novice Mexican exchange student cohort was found to provide tremendous assistance to each other’s successful socialization into new practices and environments (again, mainly through study-related interaction) through the disparate collection of expertise and the collective effort of the group in Zappa-Hollman and Duff’s (2015) study. Experiences in extra-curricular communities and discourses should also be part of the curricular activities. Following are some activity ideas that we have used in our classroom, which we also commonly find in teaching guides on language learning and teaching with technology:

“Transl8it” exercises.While mobile devices with full keyboards have made the shortening of words less necessary, their use still remains popular. Therefore, a widely practised texting exercise in the language classroom is to teach students the context for shortening words (Ray, Jackson & Cupaiuolo, 2014). Textese is commonly perceived in mobile communication, while the use of Standard English is for academic purposes. It is very common to see students writing emails containing the letter “u” instead of “you”, which causes many teachers to think the students are too informal. Thus, the “transl8it” exercises help students situate language in these two contexts, formal and informal, while becoming proficient in both. This exercise can be conducted in the classroom or through mobile phones. The teacher provides students (or elicits from students) short message blurbs to decipher and translate. An example is “btw u gonna go 2 party 2nite” (by the way, are you going to go to the party tonight?) and “gotta go bol” (I have to go; I’ll be online later). Asking students to provide both versions and use them with mobile technologies, teaches them both conventions as well as the appropriate uses and audiences of these two types of writing by situating their learning in authentic cultural contexts.

#Hashtags. Twitter is a social networking site that limits posts to 140 characters. Thus, students can practise both concise writing and abbreviating language by having to write summaries of readings, stories, and movies on Twitter. Teachers can help students situate this practice by providing authentic hashtags (labels that follow the # sign that organize tweets) that allow learners to be part of a larger community of users. Examples of popular trends are #moviereviews, #ReWriteAFilmIn5Words, #FiveWordsToRuinADate, or #fivewordstoruinajobinterview. What is more, Twitter enables teachers to broadcast to a wider audience than private texts (Ray et al., 2014).

News Hash. Depending on student proficiency, their relationship to the hashtag changes. Beginner students can practice making hashtags, but intermediate and advanced students can research them. Hashtags represent cultural currents that are localized to origin language, but speak to the global community at varying volumes. Students can seek out, collect, evaluate, synthesize, and present research to the class in their L2. Unlike limited resource and text materials in the physical classroom, Twitter provides a much greater variety of languages and topics. This gives a greater opportunity for novices to self-style as experts and scaffold their own progress (Krashen, 1985; Vygotsky, 1987). Twitter is the mechanism and the assignment; the content is student determined. Another possibility, students will translate from L1 spoken in their mind, to L1 textese via hashtags. They will then digest L1 Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) and Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skill (BICS) (Cummins, 1979), and produce a report in their L2. This is again where we see the modern blending of formal and informal as well as the importance of being able to integrate those identities. Another example of this is found on Thornbury’s blog status (http://www.scottthornbury.com/home.html). Figure 3 highlights the approach Thornbury has to self-style and scaffold his own progress.

Figure 3: Thornbury’s blog status.

“How to say more with less” exercises.For more advanced learners who have a better working idea of the phonetics of English language, teachers can introduce them to the rules of word abbreviation to save characters and comprehensibly say more in their Tweet with 140 words or less. The teacher provides students (or elicits from students) common words and elicits students for ways to abbreviate them. An example is “plz,” “ppl,” “b4,” (please, people, before) and acronyms such as “btw,” “YOLO,” “FOMO” (by the way, you only live once, fear of missing out). Students will learn new vocabulary and use in authentic cultural contexts. There is no skill level that is too advanced to benefit from Twitter practice; no matter how esteemed one’s linguistic skills, 140 characters makes every single space a precious commodity and leads to multiple false starts, rewrites, and circumlocutions.

In sum, all the strategies listed above demonstrated the integration of situated practice via social media during instruction. However, the use of situated practices via social media would not guarantee the socio-academic success of learners in the future. For instance, the new student who tweets a bum fight with an offensive epithet will not get the same traction as the new student who tweets the school mascot and a positive affirmation about the school’s dominant athletic team.

Despite the extreme approaches, the idea that tweets were an avenue of self-representation is invaluable. Tweets are the choices of representation that impact acceptance of learners, and give access to authentic language. Another example is that teacher can discuss the characteristics of good citizenship such as self-discipline with learners by reviewing tweets together.

In addition, situated practice is designed to teach the meaning and consequences of using “bad language” (e.g., foul, crude, or rude language.) in school. Teaching “bad language” is commonly avoided in schools, and, educators often leave the most delicate explanations out to avoid these topics, focusing only on conventions that students flout.

Overt Instruction

Situated practice must be supplemented with other components in order to avoid being mere repetition, and instead, teach conscious awareness and self-directed control over one’s own learning as well as instilling a receptivity to a broader spectrum of any particular digital communication (i.e. affiliations, identities, moods, etc.). Overt instruction does not equal direct transmission, drills, and rote memorization; instead it involves scaffolding, knowledge building, and being aware that what the learner already knows aids new learning. It includes collaborative efforts between teachers and students and among students themselves. It uses metalanguage, or language used to talk about language. In the framework of multiliteracies, metalanguage describes the process, elements and scaffolds that constitute the “what” and the “how” of learning (New London Group, 1996). These metalinguistic abilities are the foundation for the bridges students will build within their own Universal Grammars. These abilities will connect and hold community, school, and family social groups together. The following activity ideas are based on research suggesting that use of text message abbreviations may enhance spelling skills through phonological awareness and processing skills (Plester et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2013):

Pronunciation and spelling.As English has a non-transparent orthography (that is, the language is not written in the same way it is pronounced), texting is a great way to teach students explicit rules of pronunciation and spelling (Ray et al., 2014). For example, teaching Spanish speakers the pronunciation of the word “you” or “yellow” can be a challenge, as Spanish speakers would pronounce the first sound as /dÊ’/. Thus, instead of /ju/, Spanish speakers typically pronounce /dÊ’u/. However, with the aid of texting, students can be taught explicitly that the short version of “you” is “u” and that the word “university” is usually shortened as a “U” (capital u). Teaching students to pronounce “university” starting with the diphthong “iu” in Spanish sets the tone to then isolate the “u” and pronounce “you” written “u” as /ju/. This type of learning not only teaches students phonology, but also teaches them to recognize how phonetic rules apply to texting’s representation of sounds. In this way, students can become aware of other phonetic rules, which they can use to teach themselves other pronunciations.

SMS Short Distance Partners. Students are paired, and the pairs are then split and sent to separate expert groups. Students complete a report together, but they can only communicate through SMS. The two (4, 6, etc.,) expert groups are on opposite sides of the room. Expert group (A) researches their half of the report together (online or in-class materials) while their partner is in expert group (B) collecting and synthesizing the information they will contribute to the report. For example, topic A could be sustaining life on Mars while topic B is getting to Mars. Students will learn with their local group, but will communicate through text to complete the assignment with their distant local partner. The use of SMS enables the researcher to capture the communicative patterns on the screen and explore them afterwards. Students can even look for their own strategic moves, such as asking for more information, offering a solution, shifting from academic speech to colloquial for emphasis or out of frustration. SMS interaction models academic use of digital spaces that will be necessary in future collaboration as well as giving students an opportunity to compare and contrast the success of their SMS communication (Wood et al., 2013). This is the overt, cultivated mindfulness this framework promotes.Vocabulary and emoticons.In this activity, vocabulary is explicitly taught through emoticons. A sentence can be composed and sent using only emoticons, and the receiver must spell out what they think the message is. For example, sentences like this one could be used to teach both the present tense and also the different meanings of emoticons:

![]()

In the first case, the sentence could be “The woman eats eggs every day.” The second sentence could be “The girl runs to school.” In this way, students practice present tense. They also learn that an emoticon can be used to signify an action and a noun (notice the boy running or the silverware for a verb). There is always room for interpretation with emojis. Consider the free Shakespeare Emoji App by Arzamas in Figure 4. At times, the  represents the sea in Hamlet’s soliloquy, though it could most certainly mean wave or maybe tide. Exploring associations is one avenue where emojis can contribute to a deeper understanding of complex and domain specific terminology.

represents the sea in Hamlet’s soliloquy, though it could most certainly mean wave or maybe tide. Exploring associations is one avenue where emojis can contribute to a deeper understanding of complex and domain specific terminology.

Figure 4: Shakespeare Poetry App.

At a more advanced level, a blend of emoticons and CALP can help novices pool their collective knowledge and scaffold each other’s linguistic development. The game itself raises critical awareness of culturally shared associations (e.g., clock = time) and how easily formal and informal worlds blend together in digital spaces. Even with an increased flexibility in blended informality, text abruptness often catches your interlocutor off guard. When there is a sense of non-sequitur, your interlocutor gives a clarification request and you back up your message. Often, such transitions include a change in demeanour, but they do not have to. This template-based collaborative task allows students to explore the blended informality of the young adult and collegiate digital world. The activity can either be performed at a computer with real image searches and photo editing software, or simply on a printout. Students select a particularly moving or captivating quote, communicate it in its pure academic form, meet resistance, and alter their message in a way that the interlocutor will understand and appreciate.

Figure 5: Mobile Features.

Critical framing

Neither immersion in situated practices nor overt instruction provides students with the ability to critique a system and its relations to other systems on the basis of the workings of power, politics, ideology, and values (New London Group, 1996). Thus, the goal of critical framing is to help learners use what they practise in a situated context with consciousness of control and understanding but in relation to the socio-historical, political, and ideological system of knowledge and social practices. In order to do this, teachers should help students reframe their practices and place them in wider contexts. It is this framing that helps students detach themselves from what they are learning to constructively critique it and analyse the cultural norms. The following are some ideas.

Teaching slang. What is more motivating for students than learning authentic language? Teaching internet slang is probably a less popular topic among ESL/EFL teachers. Many may think that students are already using slang (or in some cases, they “should not” use slang), and it is the “standard” language that teachers need to be concerned about. However, even though students may be familiar with this language and some even use it quite regularly, there are two aspects that can be brought into the classroom: the history and context for the use of slang and the phonetics of the slang. When students use words like “yo,” “ima,” and “bro/broh” they may not be aware of the possible connotations, history, social uses, and indexes of the words. For students, it may appear that using these words is “cool” but without proper background, students would only be repeating phrases.

With guidance from the teacher, students can explore sites such as urbandictionary.com or others to learn some of the history, uses, and contexts in which such words and phrases are used. They can become critical users, consumers, and creators of new words. Likewise, using slang to teach phonetics is possible. For instance, why do people write “iz” instead of “is”? For speakers who do not have the voiced equivalent of /s/ this may only appear to be a fashionable way to write slang. However, once again, this could be a way to teach more than just texting. It can raise awareness of the composition of words, which may lead to self-teaching or at least noticing phonetics and pronunciation.

Whereas ubandictionary.com may be suitable for a well-contained ESL environment, for EFL students a more appropriate activity could be searching for their favourite slang or colloquial turn of phrase, “FTW”, “I can’t even”, “literally Hitler” and search for their ecological environment on COCA or a similar corpus site. This will give a grounded context for the limitations of slang and an opportunity to find ways to recast these phrases to meet the needs of academic discourse.

Identities and voice. Teaching students the meanings and use of slang words and phrases such as “YOLO” (you only live once) can also bring awareness of the identities they display in a digital space, and the complexity of those identities. Young people create slang to claim a unique identity. By celebrating and integrating the use of slang, instructors show their attitude towards the creation of individualized social identities. Students’ awareness of personal voice and cultural identity could increase significantly.

Note Taking.Students learn more when they take notes by hand; however, the majority of students reduce the number of letters when writing, creating a form of shorthand. For example, they would write “There r a # of shortcuts @ stdnts’ dispzl” on a piece of paper to mean “There are a number of shortcuts at students’ disposal”. Shorthand is composed of important lexical chunks designed for a particular unit or class topics. Writing shorthand is more effective, compared to traditional paper notes in both time and content-wise. Therefore, students should be encouraged to create individualized shorthand, and integrate it in note-taking process.

Transformed Practice

When students can critique what they learned and creatively extend and apply it to new contexts, they engage in transformed practice. Transformed practice is an alternative way in which students can “demonstrate how they can design and carry out, in a reflective manner, new practices embedded in their own goals and values” (New London Group, 1996, p. 87-88). Through transformed practice, teachers could help students re-create a discourse by engaging in it for their own real purposes. The following is a sample activity of transformed practice.

Tweeting to Storify. This is an activity that could encompass some of the activities outlined above (such as tweeting with a hashtag) to follow a piece of news, a topic, or an event with the ultimate goal to storify a report. Storify.com is a social network platform that allows users to create stories using public posts from Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Thus, a teacher will provide students with topics to “follow” and tweet during the course by making or responding to comments and “liking” posts from classmates or other users. For instance, if a teacher provides students with the hashtag trend #ThisWeeksGonnaRockBecause or #ESLproblems, students can then focus on what is important to them. Some may focus on politics, cultural issues, personal hobbies, education, struggles learning English, struggles learning a new culture, etc. Then, at the end of the week or semester, students compose reports or stories using Storify, which allows them to compile their tweets or Instagram posts and those of others in order to form a story similar to a news report. Students’ tweets may contain texting language; however, when they “storify” their reports, they can write academically to give their reports an introduction, development of their tweets, and a conclusion.

Conclusion

The pedagogical suggestions above, while not tested empirically, are aimed at inspiring teachers to create new learning experiences to accommodate learners’ multi-literacy development. Pedagogy is a variety of knowledge processes (see Cope & Kalantzis, 2016). Implicit knowledge of English rules can be transformed into concise explicit English rules using the ideas presented in this article. However, these ideas need to be situated within the country and culture of the English Language Teaching classroom. In some cases, mobile devices may not be allowed, but teaching texting can be done with a piece of paper and a pen (Hockly et al., 2013).

The idea is to take what students may already do or notice outside of school and bring it to the context of the classroom to make them aware of possible ways to enhance their learning experience through guided instruction. Not only will students learn language content, but they also learn to be digital citizens. It is also important to keep in mind that students may be from cultures where texting practices differ. In some contexts, people engage in texting practices to develop and maintain personal relationships, while in others they are mainly used to hold others at a distance. However, in the global context, teaching texting may help students become global citizens by bringing out their cultural issues and situating them in larger contexts.

Using texting language does not come without risks. Hence, it is important for teachers to carefully develop activities and not include them into their teaching as a one-time wonder, but as a long-term project or permanent element of their class structure and curriculum. Instructors need to encourage propriety in sensibility and orientation to language. This is not done by avoiding all frontiers of salty discourse, especially not if one is bringing Shakespeare, who wrote for crown and commoner alike, into the classroom. What is needed in place of avoidance is guided, complexity-minded exposure to digital discourse and social learning designed to help learners become familiar with the different contexts in which texting language is appropriate (e.g., informal settings among friends), where it is blended (academic negotiation in SMS), or not permitted (e.g., academic writing). Just as it is true that students can learn in informal environments, teachers can support this learning process not only by creating dynamic and relevant activities for them, but also by helping them become more critical and better equipped to self-regulate when sharing discursive spaces with others. Through such communicative consciousness raising activities, students transfer what they learn from school to out-of-school environments and vice versa purposefully, critically, and responsibly. The dynamic relationship among communication mode as well as the complex web of competition, support, and resistance, needs to be expanded in future research.

References

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 166–195. doi:101177/0741088307313177

Burston, J. (2014). The reality of MALL: Still on the fringes. CALICO Journal, 31(1), 103–125. doi: 10.11139/cj.31.1.103-125

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.) (2016). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Learning by design. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137539724

Crystal, D. (2008a). Texting. ELT Journal, 62(1), 77–83. doi. 10.11139/cj.31.1.103-125

Crystal, D. (2008b). Txtng: The g8t deb8. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cummins, J. (1979) Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age question and some other matters. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 19, 121-129.

Eisenstein, J., O’Connor, B., Smith, N. A., & Xing, E. P. (2010). A latent variable model for geographic lexical variation. In Proceedings of the 2010 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 1277–1287). Boston, MA: MIT.

Gillman, O. (2015, June 12). Yolo Juliet, Macbeth's #killingit: Academics horrified at 'dumbing down' of Shakespeare as the Bard's greatest works are retold in EMOJI. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3121419/Yolo-Juliet-Macbeth-s-killingit-Academics-horrified-dumbing-Shakespeare-Bard-s-greatest-works-retold-EMOJI.html

Grace, A., Kemp, N., Martin, F. H., & Parrila, R. (2014). Undergraduates’ text messaging language and literacy skills. Reading and Writing, 27(5), 855–873. doi: 10.1007/s11145-013-9471-2

Hockly, N., Dudeney, G., & Pegrum, M. (2013). Digital literacies (1st Ed.). Harlow, England: Routledge.

Johnstone, B. (2013). “100% authentic Pittsburgh”: Sociolinguistic authenticity and the linguistics of particularity. In T. Breyer, V. Lacoste, & J. Leimgruber (Eds.), Indexing authenticity. Berlin: De Gruyter. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/barbara_johnstone/58

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman.

Ling, R., Baron, N. S., Lenhart, A., & Campbell, S. W. (2014). “Girls text really weird”: Gender, texting and identity among teens. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 423–439. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2014.931290

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Pegrum, M. (2014). Mobile learning. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137309815

Plester, B., Wood, C., & Bell, V. (2008). Txt msg in school literacy: Does texting and knowledge of text abbreviations adversely affect children’s literacy attainment? Literacy, 42(3), 137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4369.2008.00489.x

Ray, B., Jackson, S., & Cupaiuolo, C. (Eds). (2014). Participatory learning. MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative. Available from https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/participatory-learning/id893789498?mt=11

Street, B., Pahl, K., & Rowsell, J. (2014). Multimodality and new literacy studies. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis, (pp. 191–200). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Vygotsky L. S., Rieber, R. W., & Carton, A. S. (1987). The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Wood, C., Kemp, N., & Plester, B. (2013). Text messaging and literacy - The evidence (1st Ed.). Harlow, UK: Routledge.

Wood, C., Meachem, S., Bowyer, S., Jackson, E., Tarczynski-Bowles, M. L., & Plester, B. (2011). A longitudinal study of children’s text messaging and literacy development. British Journal of Psychology, 102(3), 431–442. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2010.02002.x

Zappa-Hollman, S., & Duff, P. A. (2015). Academic English socialization through individual networks of practice. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 333-368. doi: 10.1002/tesq.188