Introduction

The term oral corrective feedback (CF) in second and foreign language learning research means that the person who corrects (e.g., a language teacher) provides a usually oral indication that someone else’s utterance (e.g., a learner’s) contains an error (Ellis, Lowen & Erlam, 2006). This error can be lexical, semantic, grammatical or phonological in nature. This article focuses on the treatment of phonological errors and the provision of specific teacher corrective feedback within the context of compulsory EFL classes in a large public university in central Mexico. It pursues three aims and hopes to shed some light on three research questions, for which an initial reflection and justification are offered in this section. As well, definitions of key terms are offered, and relevant literature is discussed in order to provide a theoretical framework for the present study. A methodology section is presented, followed by analysis of collected data. Finally, the research questions are answered in light of the data analysis and the literature reviewed.

Mexican university students in compulsory English courses may receive teacher CF that addresses a variety of error types. When they are asked to read aloud from written text, for example, their oral production is likely to reveal mostly phonological errors. Phonological errors, as acknowledged by Lyster, Saito and Sato (2013), have received little focused attention in CF research despite their potential to directly inhibit native speakers’ perceived comprehensibility of L2 learners’ speech. Similarly, research on CF has reported on specific CF strategies, as is the case of Lasagabaster and Sierra’s (2005) and Yoshida’s (2008) studies. However, these studies do not focus on one error type; instead, they report on a variety of occurring error types. In studies where only one of form-focused type of error is analyzed, grammatical or morphological errors, not phonological errors are common language targets for CF studies (Ellis, Lowen & Erlam, 2006; Lyster & Saito, 2010; Véliz, 2008). The first aim of this paper is to address this gap in research by focusing only on phonological errors in learners’ oral production, and on a specific CF strategy used for such errors.

The CF strategy used for correcting learners’ phonological errors in the present study is delayed correction. Second and foreign language research that discusses the pertinence of delayed CF vs. immediate CF (Lyster et al.,2013) reveals the reasons teachers have for using CF strategies immediately after the error has been produced (immediate CF), or for waiting until the learner has finished their utterances (delayed CF). In their review of research concerning the effectiveness of CF, Lyster et al. (2013) indicate that immediate vs. delayed CF is an interesting avenue for further exploration, especially when learners experience difficulty with a particular language feature. Therefore, the second aim of this paper is to address these unexplored potential benefits of delayed teacher CF.

As with other type of errors that learners produce orally in the EFL classroom, teacher CF may direct the student to self-repair (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Lyster & Saito, 2010; Yoshida, 2008). In accordance with sociocultural approaches to learning where negotiation, interaction, collaboration and self-regulation are highly valued (Lyster et al., 2013), self-repair can be seen as a specific behavior leading to self-regulation, which in turn characterizes successful autonomous language learners (Luna Cortes & Sánchez Lujan, 2005). Self-repair, also known as self-correction in CF research, has been positively perceived by language learners and teachers, as it is believed to be conducive to meaningful learning (Lyster et al., 2013; Yoshida, 2008). Thus, the third aim for the present study is to determine whether the specific teacher CF strategy used here may in any way orient learners to self-correct their phonological errors.

Our third aim could well enable us to explore whether self-correction of phonological errors can encourage any specific autonomous learning behaviors in our university students. Previous research on autonomous learning has inquired about teachers’ and students’ beliefs, views and dispositions to its promotion or willingness on their part to embrace it in EFL settings (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012; Buendía, 2015; Picón Jácome, 2012). Nevertheless, it has not addressed specific EFL classroom actions or behaviors that could potentially encourage autonomous language learning. These specific behaviors may pave the way to a more extensive implementation of autonomous language-learning procedures in the future.

Our interest in fostering autonomous learning behaviors in our university students resides in the belief that our Mexican university students do not have to conform to the claimed “traditional and paternalistic education” (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012, p.72) that has prevailed in Mexico for many years, and that helping them to become aware of their language learning potential can enable them to exercise any kind of learning at will (Ikonen, 2013; Luna Cortes & Sánchez Lujan, 2005). Being able to take control over their own EFL learning, Mexican university students in large public universities may be able to: (a) move their language learning forward to achieve personal academic goals, or (b) successfully keep up with usually quick-paced compulsory EFL courses.

For the purposes of this paper, teacher corrective feedback will be defined as the teacher’s delayed provision of the correct language form in response to the presence of a phonological error in the stream of recorded oral language produced by a pair of language learners. Self-correction will be understood as the student’s provision of the correct phonological form after receiving teacher CF. Self-correction will also be considered a specific behavior deriving from self-regulation processes that autonomous learners are believed to undertake. These definitions are derived from the theoretical discussion in the literature review below. This paper aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How do students feel about the teacher corrective feedback they receive for oral production assignments in their compulsory EFL university courses?

RQ2: What specific actions do students in compulsory EFL university courses take to self-correct their oral production?

RQ3: To what extent do our teacher corrective feedback strategies encourage learner self-correction and autonomy in EFL university students?

Literature Review

Teacher Corrective Feedback and Self-correction of Oral Errors

Oral corrective feedback can occur in naturalistic and classroom settings, as it entails the presence of an error in the stream of language produced by a language user or learner, and the intention to deal with such an error on the part of interlocutors or producers themselves. Ellis, Loewen and Erlam (2006) define corrective feedback as “responses to learner utterances that contain error” (p. 340). This response to learners’ utterances is assumed to come from a teacher or instructor, which is why corrective feedback is commonly understood as teacher corrective feedback in recent second language learning research (Lyster et al., 2013). Ellis, Loewen and Erlam (2006) further distinguish three types of teacher responses: “(a) an indication that an error has been committed, (b) provision of the correct target language form, or (c) meta-linguistic information about the nature of the error, or any combination of these” (p. 340).

The type of response that teachers use when dealing with an oral error depends on factors such as the type of error (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Yoshida, 2008), and individual learner differences such as age, language proficiency, believed ability to deal with class-fronted correction, and language learning styles (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Lyster & Saito, 2010; Lyster et al., 2013; Yoshida, 2008). These studies acknowledge that instructors usually have to consider all of these factors in a matter of seconds. Some researchers (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005) point out that instructors who know their learners well are better equipped to determine whether specific language learners will benefit from one type of error correction or another. In many EFL classes, especially large classes, teachers have insufficient time to get to know learners’ needs or to deliver CF that matches these individual needs (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Lyster & Saito, 2010; Yoshida, 2008).

The teacher responses to learner utterances containing error in second and foreign language research can be classified into corrective feedback types or corrective feedback (CF) strategies. Based on previous research, Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012) as well as Lyster et al. (2013) classify types of CF as: (1) those where the correct forms are provided or elicited; (2) those where the teacher reformulates the student’s erroneous utterance or where he prompts student self-correction; and (3) those where CF is more implicit or explicit in nature (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Ellis Loewen & Erlam, 2006; Tedick & De Gortari, 1998; Véliz, 2008). Types of CF, such as recasts, explicit correction, elicitation, andclarification requests, are identified and discussed in CF research from different angles. Research on CF types or strategies has mostly set out to determine teachers’ choice or preference for one or another (Baker & Westrup, 2003; Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Yoshida, 2008). Some more research has tried to determine effectiveness of one type/strategy over the other (Ellis Loewen & Erlam, 2006; Lyster & Saito, 2010) and, very importantly for the present study, some research has also tried to determine students’ preferences or perceptions about teacher CF (Yoshida, 2008; Zacharias, 2007)

In a thorough review of research about learners’ CF preferences, Lyster et al. (2013) discuss the following key issues: (1) it informs practitioners about which types of CF strategies their students prefer, which in turn (2) can lead to teaching practice and CF that match these learner preferences better. Learners’ preferences about types of CF appear to relate closely to instances where teachers try to push learners to self-repair. Research indicates that teachers who offer cues to help students notice the error and correct it, encourage significant learning in their students (Hong, 2004, Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Tedick & De Gortari, 1998). Moreover, this same research also points out that learners in fact may welcome the opportunity to work out things for themselves (Yoshida, 2008).

Nevertheless, research also shows that the CF strategies that teachers use to encourage self-repair may be ambiguous for some language learners (Ellis, Lowen & Erlam, 2006; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005), which could generate confusion, embarrassment or even anxiety in language learners (Oxford, 1999). Secondary language learners in Martínez Agudo’s (2013) study about how they emotionally respond to their EFL teacher CF, for example, report feeling upset when they do not actually understand what the teacher is correcting. Some learners’ preference for more explicit and direct CF strategies as reported in Ellis, Lowen and Erlam (2006) could be related to similar feelings experienced by learners. Martínez Agudo (2013) also warns about potential affective damage that CF might cause among students in classroom situations if not used cautiously and tactfully. Fortunately, CF researchers show constant concern for promoting strategies that are more face-saving, less intimidating for students (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Lagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Lyster et al., 2013; Yoshida, 2008)

Most of the research on CF implies that it is the teacher who provides CF. However, there may be other corrective feedback providers in the classroom. According to Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012), potential providers of CF in the classroom include: teachers, peers, and the speakers themselves. Several studies have investigated corrective feedback to determine effectiveness and/or preference for these three alternatives in language learning. In research on peer correction in writing, for example, Zacharias’s (2007) study reveals a strong belief on the part of learners that peer comments and corrections on their writing were not as well informed as those of their teacher, and participant teachers in the same study report a similar phenomenon in their own classrooms. In their review of current research about oral CF, Lyster et al. (2013) point out that peer CF can be more face-threatening and less trusted than teacher CF. Similarly, the EFL Mexican teachers participating in Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz’ (2012) study report on the limited popularity that oral peer correction has among their own students. Moreover, these teachers believe in first providing CF themselves, next in eliciting self-CF, and, only finally, in eliciting peer CF (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012). Despite these adverse scenarios, the two teacher researchers in the present study believe that self- and peer-correction options may be both welcomed by and effective for learners if careful and tactful CF strategies are used (Budden, 2008; Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Martínez Agudo, 2013).

One of the CF strategies employed by teachers to free individual students from the risk-taking moment in which they have to self-repair is to use whole group correction instead of individual correction (Harmer, 2006; Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012). The individual vs. whole group CF possibility has also been investigated in terms of effectiveness, choice and preference on the part of both students and teachers (Ellis, Lowen & Erlam, 2006). However, an alternative that is not mentioned in the literature is small-group or paired CF, which would be significantly helpful to describe the type of CF that is employed in the present study. Another strategy that intends to free students from feeling at risk or face-threatened in class-fronted situations during immediate CF is to wait until the learner has finished their utterance. This strategy is known in CF research as delayed CF. In the immediate vs. delayed feedback dichotomy in CF research, delayed CF is said to favor fluency (Budden, 2008; Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012), but it can also be used to increase accuracy. Interestingly, in CF carried out in a study by Yoshida (2008), for example, delayed recasts were not initially considered. In fact, the category was added at the moment of data analysis. The results show, however, that delayed recasts only accounted for the 1% of CF incidents. As Lyster et al. (2013) acknowledge, the delayed vs. immediate distinction affects teachers’ CF behavior. However, it is not clear how delaying CF influences its effectiveness.

CF research indicates that adult learners at the earliest stages of language learning exposure and/or proficiency may not be skilled at recognizing cues or understanding less explicit CF strategies used by teachers (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Velíz, 2008; Yoshida, 2008). Similarly, learners are more likely to perceive that there are lexical or phonological errors than semantic or morphosyntactic errors (Lyster et al., 2013). Unlike grammatical or lexical errors, phonological errors may require different CF protocols, and thus CF types employed may not be as varied. Indeed, phonological errors might frequently require direct, explicit CF strategies if errors are to be corrected. While the participants in Lasagabaster and Sierra’s study (2005) favored explicit information, such as comparing L1 and L2 pronunciation patterns, Lyster et al. (2013) acknowledge from reviewed studies that pronunciation-focused recasts can benefit learners greatly in terms of their L2 pronunciation development. Despite the fact that there may be some discrepancy about correcting learners as a group or using written and/or visual support to correct phonological errors (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005), available research does not seem to suggest that CF strategies will move towards the more implicit, indirect side of the CF spectrum. The likelihood of eliciting correct versions of mispronounced lexical items or asking learners to self-correct is reported to be very limited, yet not non-existent.

Language Learner Autonomy and Self-correction

Learner autonomy is defined by Benson (2001) as “the capacity to take control over one’s learning” (p. 2). He also points out that it is not a learning method, but rather “an attribute of the learner’s approach to the learning process” (p. 2). Among the claims about autonomy that he considers worth examining, Benson (2001) lists these: (1) it is naturally present to different degrees in every person; (2) learners can be trained to utilize autonomy; and, (3) it has the potential to ensure better language learning. Researchers and practitioners may approach the study of learner autonomy from different angles. For instance, Ikonen (2013) identifies three angles: (1) the promotion of learner autonomy, (2) the effects and effectiveness of learner autonomy, and (3) the measurement of learner autonomy. According to her, the promotion of learner autonomy has to do with perceptions and readiness of language teachers or language students to develop learner autonomy. These perceptions are often revealed by teachers’ and students’ beliefs, attitudes and experiences, which in turn affect their willingness to embrace autonomous learning.

Since autonomous learning concerns both teachers and students, it is widely accepted that both actors should have opportunities to develop autonomy in the learning-teaching process. According to Balçıkanlı (2010), ideally, teachers should have developed themselves as autonomous learners so that they can model such attitudes and behaviors for their students. Also, it is best when such first-hand experience is positive; otherwise, students’ autonomous learning potential may be inhibited instead of encouraged. Similarly, Borg and Al-Busaidi (2012) point out that developing learner autonomy should be a facet of in-service teacher education. When teachers are guided to manage their own learning, they are in a stronger position to train their own students to do so. Fandiño (2008) asserts that EFL teachers can achieve autonomy as learners when they engage in critical reflection about their own teaching practice, for example, when they:

…monitor the extent to which they constrain or scaffold students’ thinking and behavior, when they reflect on their own role in the classroom, when they attempt to understand and advise students, and, ultimately, when they engage in investigative activities. (p. 203)

Autonomous EFL teachers, therefore, are practitioners who engage in critical, reflective teaching-learning and who develop expertise of their own as a result. Fandiño (2008) argues that the more consciously developed these skills are in EFL teachers, the more naturally it could be for these teachers to cultivate autonomous learning skills in their EFL learners.

Concerning students’ ability to develop learner autonomy, some studies report on students’ beliefs about autonomy in the EFL field. Frodden and Cardona (2001), for example, report that it is crucial that students and teachers share similar beliefs and expectations about what occurs in language classrooms. In contrast, their views on learner autonomy may diverge sharply. For example, teachers may judge students more able to be autonomous than they are; on the other hand, Frodden and Cardona explain, learners may “expect the teacher to make decisions regarding their learning” (p. 100). As Frodden and Cardona (2001) acknowledge, traditional views may come from either learners or teachers, and it is the teachers’ job to mediate between the two perspectives.

Of importance is teachers’ flexibility and sensitivity towards what their students perceive as language-learner autonomy. Negotiating the line between where the teacher’s job ends and where the students’ responsibility begins may lead to conflict. Buendía’s study (2015), for example, tries to determine Colombian and Chinese university students’ perceptions of or readiness for learner autonomy. A comparative analysis of the responses from both groups indicates that some of these Colombian and Chinese university students’ attitudes and perceptions may be dictated by cultural aspects. Likewise, researchers such as Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012) have indicated that some education systems may be characterized by a traditional and paternalistic approach to teaching and learning, which could potentially hinder teachers’ efforts to implement autonomous learning practices. Although it can be useful to gain a better understanding of learners’ views in order to diagnose the potential of such efforts, EFL teachers should not simply give up. Picón Jácome (2012) illustrates how practitioners can engage in careful observation, reflection and planning of strategies that could lead to more autonomous learning behaviors in language learners. Similarly, teachers may have to learn to characterize individual learners as organically or systematically as they can in order to personalize autonomous learning expectations about individual students as accurately as possible (Luna Cortes & Sánchez Lujan, 2005).

Asking learners to provide their viewsabout the implementation of teaching strategies that encourage autonomous learning behaviors is a key ingredient to developing self-awareness and meta-cognition in students at later stages (Picón Jácome, 2012). Both Borg and Al-Busaidi’s (2012) study on university teachers and Buendía’s (2015) study on students’ views and attitudes towards language learning autonomy report on student readiness for autonomous learning. Both studies claim that readiness depends on how students view language learning as a whole. Their perspectives may associate language learning with the mastering of skills or sub skills. Also, their views about language learning may indicate what exactly they feel they can control. This paper intends to explore how ready university students are for autonomous language learning by focusing on a concrete language learning assignment and the teacher corrective feedback that students receive for it (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012; Buendía, 2015). In other words, it aims to address autonomous language learning behaviors related to oral language production that may result from feedback provided to students.

The connection between teacher CF strategies and learner autonomous behavior is discussed in the work of Zacharias (2007), Yoshida (2008) and Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz (2012). Zacharias’ (2007) research analyzes Indonesian learners’ views about the CF they receive for their English written production. Yoshida (2008) reports on English-speaking learners’ views about the CF teachers gave them for oral production of Japanese as a foreign language. Finally, Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz (2012) describe Mexican learners’ preferences based on the teachers and not the learners themselves. In contrast, the present study tries to address Mexican learners’ preferences about the CF given to them by teachers for their oral production as reported by the learners themselves.

The promotion and initial diagnosis of the effects and effectiveness of learner autonomy (Ikonen, 2013) through the conscious design of appropriate learning and teaching conditions (Benson, 2001) may have so far been met. Ideally, the next step should be to explore the possibility of measuring learner autonomy. Learners’ perceptions about how well they believe they can exercise autonomous learning behaviors would require some degree of self-awareness and meta-cognitive skills. They could be asked, for example, about the value of repeating aural-oral tasks (Lambert, Kormos & Minn, 2017) and the corrective feedback they are given for it (Budden, 2008; Yoshida, 2008).

From cognitive and sociocultural perspectives, the promotion of corrective feedback strategies (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012) that encourage students to correct themselves or each other while they are working in pairs (Baker & Westrup, 2003) or interacting with the teacher (Tlazalo Tejeda & Basurto Santos, 2014) can be highly beneficial for the development of self-regulation processes which lead to meaningful and successful language learning. These self-regulation abilities could contribute to the development of language learning autonomy that Mexican EFL teachers would want for their students (Luna Cortes & Sánchez Lujan, 2005).

Methodology

This two-teacher researcher study took place at a large public university in central Mexico. This research is framed as action research (AR) or teacher research, as we wish to become language teachers who take “informed professional judgments that are conductive to generating improvements” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004, p. 9) in our teaching and in our students’ learning. McNiff (2014) and Burns (2010) describe action research as a permanently forward-moving cycle of four steps: 1) planning; 2) action; 3) observation; and 4) reflection. Action research is used to face dilemmas or solve problems. It is particularly relevant for us that AR implies working collaboratively with other teachers (Edwards & Burns, 2016) and making a commitment to one’s own improvement (McNiff, 2014). Both teacher researchers in this study feel strongly committed to improving of our teaching practice and firmly believe that our collaborative AR work has advanced this goal.

According to McNiff (2014), there are researcher positionality distinctions in AR. These positionality distinctions are used in the present study to identify the two teacher researchers as: (a) an outsider teacher researcher; and (b) an insider teacher researcher. Such an arrangement was chosen in an effort to increase objectivity when data were to be analyzed and interpreted. It was agreed that the outsider teacher researcher would collect data from student groups where the insider teacher researcher was the participants’ EFL course teacher. The outsider teacher researcher would come in the insider teacher researcher’s classrooms to collect data from the students. Both teacher researchers would contribute to the processing and analysis of collected data.

Participants and Context

Participants were 78 EFL undergraduate accounting majors enrolled in A1 general English courses taught by one of the teacher researchers. Students at this university take four compulsory Core Curriculum EFL courses that aim to take students from A1 to A2+, as described by the Common European Framework of Languages (Council of Europe, 2012). The main objective of the courses is to improve both receptive and productive skills as well as to work on basic grammar and vocabulary. Students take four 50-minute lessons a week per course in classes of 35 to 55 students. The average attendance per classroom after diagnostic and placement exams is 35 students. Participants, aged 19-20, included 40 males and 38 females distributed in three groups of 29, 30 and 31 students each. All 78 participants were involved in classroom activities designed to elicit student oral production, and answered a printed survey where their views about teacher corrective feedback procedures were collected. These classroom activities and data collection procedures are described below.

Design of Classroom Activities, Data Collection Instrument, and Procedures

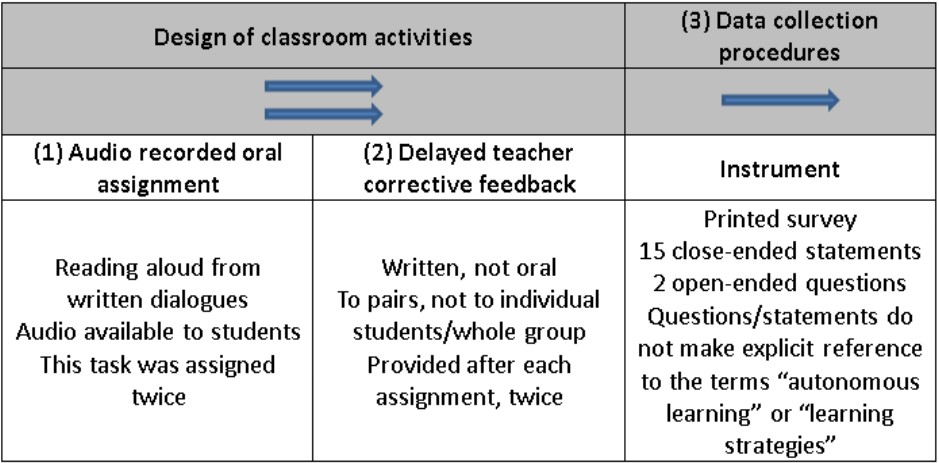

This section describes the mixed methods approach that was used to collect students’ views about delayed teacher corrective feedback. As a first step, classroom activities to elicit student oral production were designed and implemented. A week later, written delayed teacher CF was provided, and the process was repeated within the following three weeks. Finally, about a week after students received delayed teacher CF for the second time, their perceptions about the use of this specific CF strategy were collected. Each phase of our data collection process is described and summarized below in Table 1.

Table 1. Classroom activities and data collection procedures.

Audio Recorded Oral Assignment to Elicit Student Oral Production

The classroom activities that were designed to elicit oral production from students consisted of reading aloud from written text and audio recording this exercise. These were course assignments, and students were asked to do two assignments of this type. Design of these assignments is similar to a study by Tlazalo Tejeda and Basurto Santos (2014), where students were asked to read aloud from written text and to be audio recorded. It also resembles Lambert et al.’s (2017) study, where besides examining repetition effects on students’ performance, they also considered the participants’ perceptions about the value and usefulness of repeating aural-oral tasks.

There are, however, differences in design. For instance, while Tlazalo Tejeda and Basurto Santos (2014) and Lambert et al. (2017) used monologue-type texts, we chose two-participant dialogues as the written texts to be audio recorded. There were two reasons for this decision. First, we wanted students to undertake this task with company, which might encourage peer support and/or learning from each other. It was hoped that pairs of students would remind each other of in-class exercises and advice they were given during the course to improve pronunciation of individual words and connected speech. Second, being classroom teachers who had to grade students’ assignments following the pace of our regular EFL compulsory course at university, we had to think of ways to maximize our time and energy, especially because there were other course assignments. Half of the dialogues were taken from our course book, and the other half from the English Language Listening Library Online (ELLLO) web page (Beuckens, 2016). Eighty-one out of the 93 students distributed in three groups completed the two assignments. Appendix A shows how these two assignments were presented to the students.

Delayed Teacher Corrective Feedback

A week after students submitted their recordings, they were given explicit delayed teacher corrective feedback. Appendix B shows a sample corrective feedback sheet given to students. The first reason to give learners delayed CF instead of immediate CF was to create face-saving circumstances for students (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Martínez Agudo, 2013; Yoshida, 2008), regardless of how ready they were to receive immediate, class-fronted CF without feeling negatively affected. There were some students who did not manifest persistent difficulty articulating words when reading aloud from written text in some classroom activities; however, we did not want to assume that all the students were eager to be corrected in front of their peers. Moreover, being A1 learners, these students might not have had much experience with language learning. It could have been counterproductive to expect them to notice and respond to more indirect types of CF (Martínez Agudo, 2013; Yoshida, 2008). Finally, as Lyster et al. (2013) point out, learners are more likely to be able to self-correct subject verb agreement, for example, than phonological errors.

Delayed teacher CF procedures occurred as follows: While the whole group was busy working on another task, pairs were approached to give them hand-written feedback sheets with both their names on it (see Appendix B). Brief oral indications were given: “Hello. Here’s some feedback on your last assignment. It is a list of words you did not pronounce so well, and between slashes is information on how to pronounce them. You can practice them on your own if you wish. Please keep this paper until our course finishes. Thank you.” Receiving teacher CF in pairs, we believe, might help each student feel that they were not alone. Although there is no research about providing CF to pairs of students, some researchers (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012) believe that whole group correction is less harmful than individual correction. Since whole group correction is also perceived as being much less effective (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Lyster et al., 2013), we would like to suggest that pair correction might be somewhere in between in terms of effectiveness, especially when both students have the same phonological error, as is the case of the present study. In addition, when corrected orally, students may not keep notes or fully understand what is being corrected. In contrast, written corrections might prove useful to “facilitate the noticing” (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005, p.116) of phonological errors for some learners. This is why delayed CF was provided in writing.

Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

To collect students’ views about the usefulness (or lack thereof) of the delayed teacher corrective feedback, we used a printed survey organized in four sections (see Appendix C). We distributed and collected the surveys on the same day in all three groups, within the last 10-15 minutes of their lesson. The survey is in Spanish, and it shows a sample of the written delayed CF given to students after each assignment so they know exactly what the survey is about.

To design our own survey, we initially considered instruments such as the ones used in the studies by Borg & Al-Busaidi (2012), Buendía (2015), Lambert et al. (2017), and Tlazalo Tejeda and Basurto Santos (2014). However, we felt that these might be too long. Most importantly, we did not want to make any explicit reference to autonomous learning or to the conscious use of language learning strategies. As a result, our instrument asks the participants to report on behaviors related to oral language production. We feel that these behaviors are desirable for the development of autonomous language learning in this specific area.

Section One lists four statements about clarity of feedback, its usefulness to pinpoint areas to improve, how well it encourages peer correction and team work, and its usefulness as a study guide. Each of these four statements appears on a four-point Likert scale as follows: totally agree – agree – disagree – totally disagree. The following sections in this survey display statements that were delivered to students during the course as a piece of advice, an explicit instruction for an activity or exercise, or a casual comment about ways to improve their aural skills. These statements are grouped in preparation actions and actions after they received feedback, Sections Two and Three respectively.

Section Two inquiries about whether or not pairs carried out the six actions indicated in the same number of statements to prepare for the recording assignment, such as listening to the audiotaped dialogues first, rehearsing together, and listening to their own recordings. Section Three asks the participants to indicate whether or not they have used the feedback they were given to carry out any of the five post-feedback, self-initiative activities. Examples of such activities include: listening to the original audio recordings of the dialogues to hear the words they were asked to pay attention to, repeating the words listed on the corrective feedback sheet as indicated between slashes, and listening to how the listed words are pronounced by technology-assisted resources such as Google translator, or online dictionaries (Cambridge University Press, 2017; Pearson, 2017). Finally, the participants are asked to answer two open-ended questions. The first asks them to suggest how the corrective feedback they receive could be more useful to them. The second asks them to indicate what activities they would recommend to someone who wishes to speak English with very good pronunciation.

Analysis and Discussion

This section reports findings by discussing how the quantitative results elicited in Sections One, Two and Three of our survey contrast with answers to the two open-ended questions at the end of this instrument. We structured the analysis of both our qualitative and quantitative data according to our research questions.

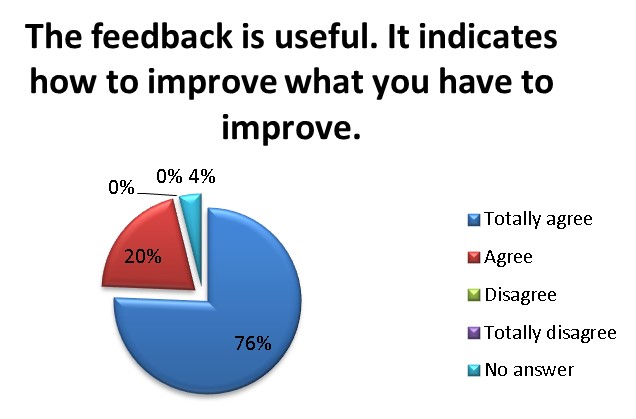

RQ1: How do students feel about the teacher corrective feedback they receive for oral production assignments in their compulsory EFL university courses?

To answer this question, we analyzed the four statements in Section One of the survey and the answers to the first open-ended question. As it can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, none of the participants marked the corrective feedback as not useful at all, whereas an overwhelming majority of the participants indicate that the feedback sheet given to them is clear (95%), and that it tells them how to improve what they need to improve (96%).

.jpg)

Figure 1.Students’ perception of clarity of CF.

Figure 2. Students’ perception of usefulness of CF

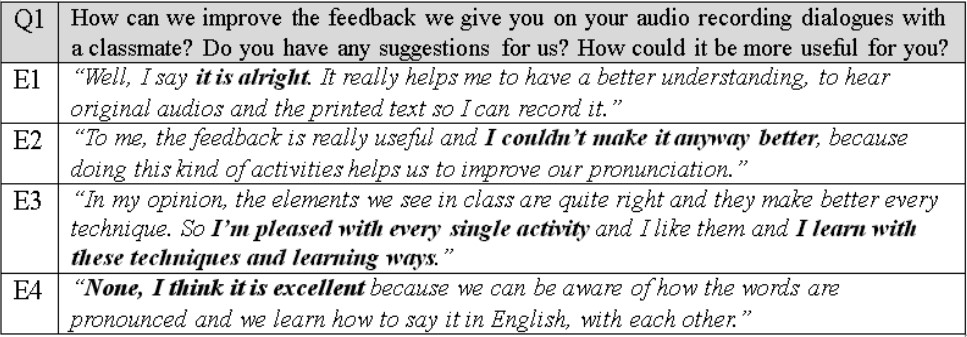

Moreover, 14 answers to the open-ended question show that the assignment and the corrective feedback were welcomed and accepted. The question asks the participants to describe how to improve the corrective feedback they received. As we can see in Table 2, four of these 14 participants explain that they believe that no further improvements for the assignment or the corrective feedback are necessary. It is relevant for us that one of them points out that he/she can be aware of how words are articulated and that he/she can learn it in the company of others. These four participants, therefore, manifest being fully satisfied with the CF method under study.

Table 2. Extracts from answers to open-ended question one.

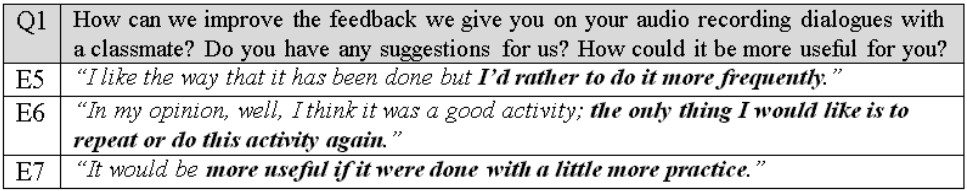

However, three of these 14 participants explain that this kind of assignment should be done more frequently, and we can assume that they would expect to get teacher corrective feedback more frequently as a result of this improvement (see Table 3).

Table 3. Extracts from answers to open-ended question one.

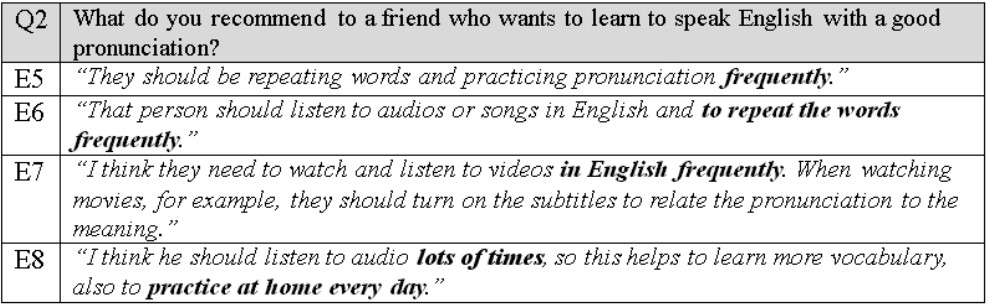

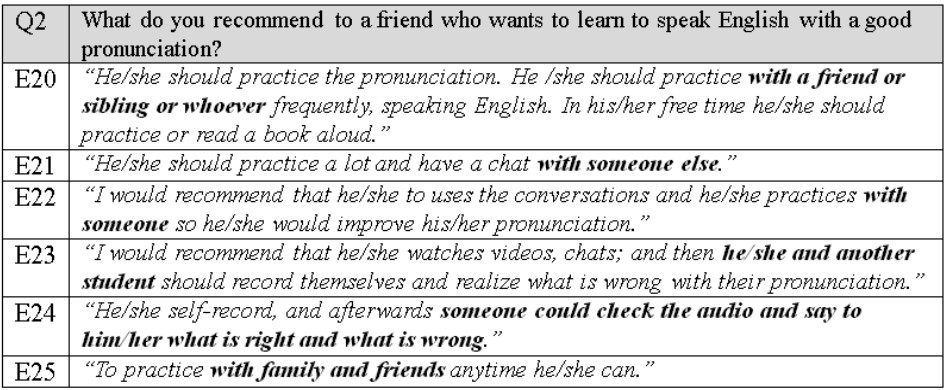

Participants, 25% of them, use time expressions such as “frequently, every day, constantly and several times” when they answer the same open-ended question. Similarly, when the participants answered the second open-ended question where they are asked to indicate what they would recommend a friend who wants to learn to speak English with a good pronunciation to do; frequency-related phrases stand out in their answers (see Table 4).

Table 4. Extracts from answers to open-ended question two.

CF research reveals that learners may want to receive more feedback than teachers give (Lyster et al., 2013). This study appears to confirm that these participants also want more feedback and more frequent feedback. In addition, we could argue that the participants seem to be aware of the need to do language learning tasks at regular intervals. Most teachers and teacher researchers would agree that learner awareness of what is needed in order to succeed in learning goals or academic achievement is key for students to actively develop learning strategies and, eventually, learning autonomy.

RQ2: What specific actions do students in compulsory EFL university courses take to self-correct oral production?

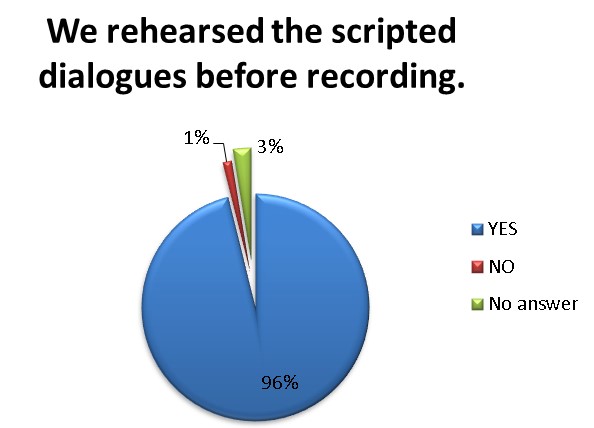

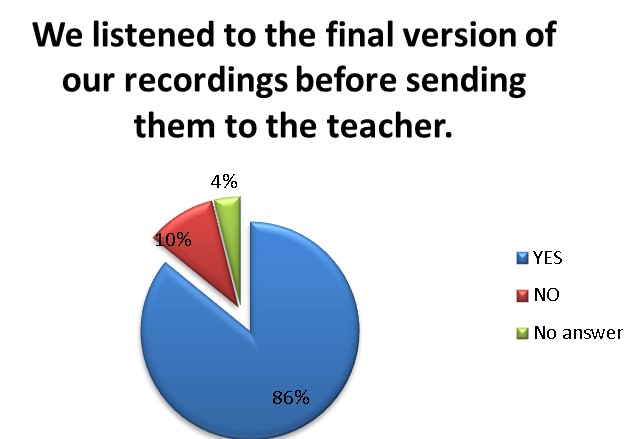

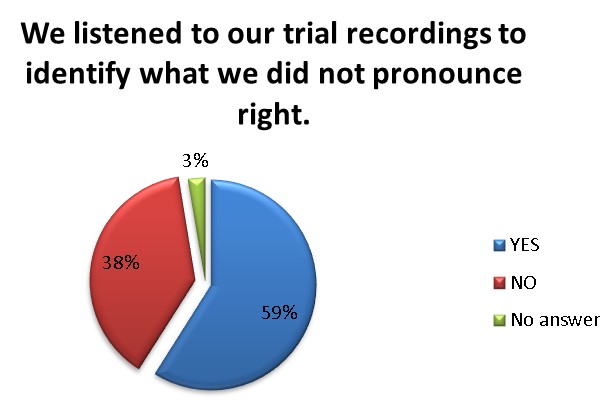

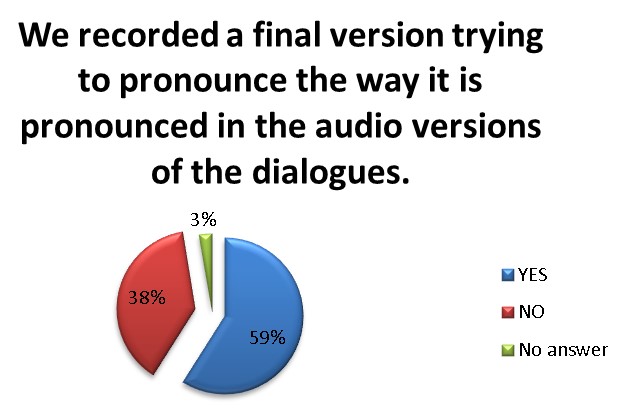

This section deals with the specific actions that participants report they undertook to prepare for the oral assignment described in this study. We answer RQ2 by analyzing the six statements in Section Two, as well as the answers to the two open-ended questions in our instrument. According to survey results, participants seem to ascribe importance to preparation activities. As it can be seen in Figures 3 and 4, an overwhelming majority of the participants claim to have rehearsed the scripted dialogues before recording them (96%), and quite a few (86%) state that they listened to the final version of their recordings before sending them to the teacher.

Figure 3. Students’ reported preparation actions--rehearsing

Figure 4. Students’ reported preparation actions—audio checking

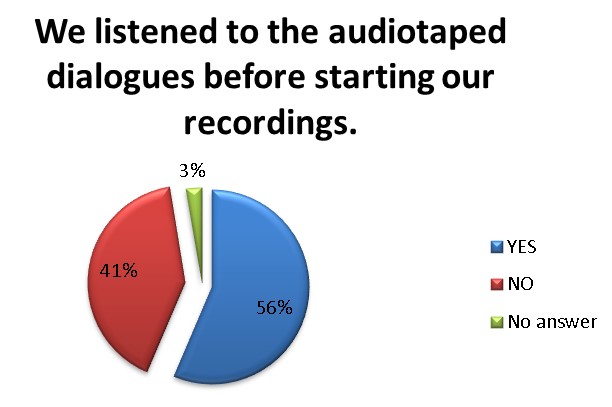

However, as it can be seen in Figures 5, 6, and 7 below, they did not rely much on self-study audio materials or on their listening skills to help in rehearsal or self-evaluation. Survey results about preparation activities show that only 56% of the participants listened to the audiotaped dialogues before making their own recordings. Moreover, only 59% of the participants listened to their own recordings to identify phonological errors. In contrast, 59% of the participants indicate that they tried to imitate an audio version of the dialogues when making their own recording.

Figure 5. Students’ reported preparation actions—listening to models

Figure 6. Students’ reported preparation actions—evaluating trial recordings

Figure 7. Students’ reported preparation actions—imitating models

From these data, we assume that students relied more on the written than on the audiotaped scripts of their dialogues, even when they had both available. They may think that listening to the audio versions is time consuming or unnecessary. Or, it may simply be too hard to pronounce “child,” “museum” or “enjoy” for instance, even if they listen and read them at the same time. Similarly, comparing themselves to the original audio to identify their own mistakes may be beyond their level of expertise. Perhaps, as explained by two of the participants, some students still need to listen to the teacher say things more slowly than audio recordings available. Requests from the participants for audio recordings to play more slowly can be seen in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Extracts from answers to open-ended question two.

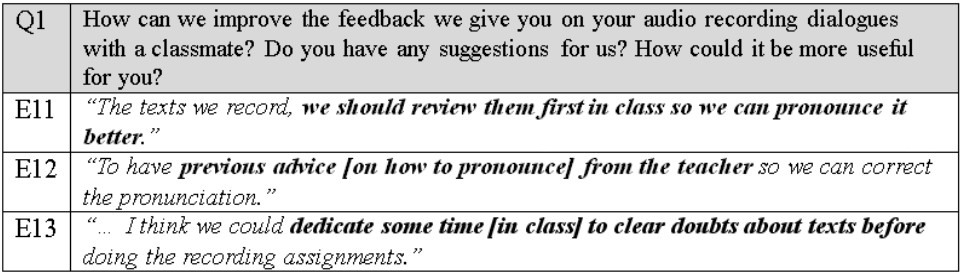

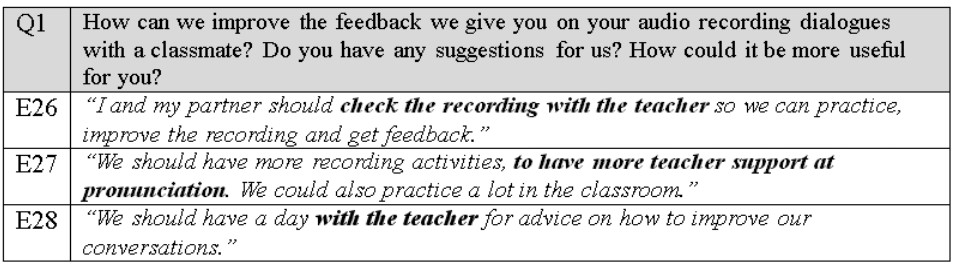

In addition, ten participants suggest some pre-teaching before this assignment. This pre-teaching may take a variety of forms, such as simply listening to students articulate the dialogues and offering CF, or simply allowing time for students to rehearse. In other words, these participants appear to need the presence and supervision of the teacher to do the task confidently. Suggestions from participants can be seen in Table 6 below.

Table 6. Extracts from answers to open-ended question one.

In sum, although the participants were eager and enthusiastic about preparing their recorded oral assignments, they did not avail themselves of the audio self-study materials available to them. Moreover, they expressed the need to have a teacher model the audio versions for them at a slower pace. Though these behaviors show limited learner autonomy, they do reveal how students often behave and why.

RQ3: To what extent does our teacher corrective feedback encourage learner self-correction and autonomy in EFL university students?

To answer this question, we analyzed the five statements in Section Three of the survey, as well as the answers to the second open-ended question. Some answers from the first open-ended question are offered. Despite the fact that the statements and the open-ended questions did not contain any explicit reference to self-correction or learner autonomy, the participants referred to these concepts in their answers.

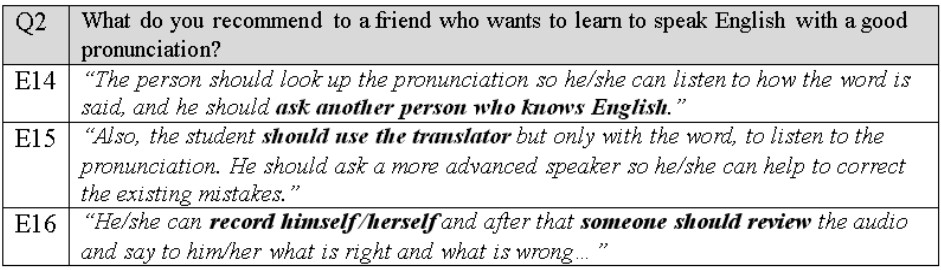

Taken as a whole, the participants’ acknowledge that a person who wants to speak English with high intelligibility (Harmer, 2006) can easily succeed without the presence of a language teacher. In the three extracts in Table 7, the participants suggest that people listen to how the word is pronounced, which is a behavior they did not practice. Moreover, three of the participants (see Table 7) suggest that a person who wants to learn to speak the language with good pronunciation should, on their own, use Google translator (see E15 in Table 7 below) or ask someone other than the teacher, and repeat the correct pronunciation.

Table 7. Extracts from answers to open-ended question two.

Similarly, four more participants (see Table 8) suggest that this person should do exactly as they did for these course assignments. It is remarkable that seven participants would actually suggest that people record themselves and listen to their recordings for self-correction in order to learn to speak with better pronunciation.

Table 8. Extracts from answers to open-ended question two.

Some of their suggestions even include pair work and the possibility of relying on people other than their English course teacher. Samples of these suggestions can be seen in Table 9.

Table 9. Extracts from answers to open-ended question two.

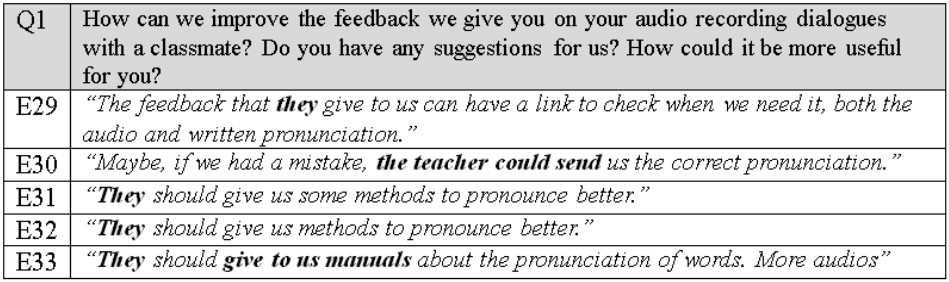

There seems to be a constant tension between the need to be supervised by a teacher and the willingness to take responsibility for one’s own learning. While there are some learners who can be more resourceful and willing to take risks as we have shown above, some others insist on the presence of a teacher for effective correction work. Samples of the latter are shown in Table 10, in response to question one.

Table 10. Extracts from answers to open-ended question one.

Moreover, the participants seem to be ready to use corrections the teacher sends to them via email, or to use any printed materials they are directed to. In case there are any digital resources for language learning, the participants seem to be ready to trust the teacher’s judgment in terms of recommendations. Samples illustrating these participant requests to question one can be seen in Table 11.

Table 11. Extracts from answers to open-ended question one.

It is interesting that in these last four comments the students used the impersonal form in Spanish, implying the use of an entity outside of their own control. By saying that they should be given something from an unidentified someone, they seem to be placing a lot of importance on being assessed by some kind of expert who knows better. Apparently, they believe that the teacher’s judgment and advice are what will really help them learn.This use of impersonal language may have to be explored in depth in a further study.

Discussion and Recommendations

In this section, we offer a reflection related to our research questions and concluding remarks. In addressing RQ 1 (How do students feel about the teacher corrective feedback they receive for oral production assignments in their compulsory EFL university courses?), we have reported on three areas related to the CF research discussed above: (1) emotional responses to teacher CF; (2) effectiveness of teacher CF strategies; and (3) learner preferences for types of teacher CF. The participants in this study emotionally responded positively (Martínez Agudo, 2013) to a specific type of CF that was explicitly designed to protect them from possibly embarrassing class-fronted CF circumstances (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012).

The learners were satisfied, perhaps due to the perceived clarity and usefulness of the type of CF given to them. Therefore, we can say that no signs of ambiguity that may have upset or confused the participants were reported or perceived (Martínez Agudo, 2013). Since we were not sufficiently familiar with the participants’ characteristics as more apprehensive or more independent kinds of learners at the time of teacher CF delivery (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012; Martínez, 2013; Yoshida, 2008), we designed CF that avoided immediate, class-fronted feedback risks. Not having experienced such feelings, the design of the delayed teacher CF provided in this study seems to have isolated the desired levels of effectiveness of CF strategies. We could also claim that the use of the CF strategy in this study was also helpful to reveal the likelihood of the participants’ attitudes towards other characteristics (e.g., explicit vs. implicit) and elements at play during CF processes (e.g., peer correction) that recent research has discussed, such as metalinguistic features or CF providers.

In addressing RQ 2 (What specific actions do students in compulsory EFL university courses take to self-correct oral production?), we can claim that EFL learners in this study ascribed importance to correctness. Further, even though they may not be keen on taking risks when producing language orally, they see oral assignments as an opportunity to further improve their oral language proficiency. The teacher CF given to them focused on phonological errors only. This focus was positively acknowledged by the participants in this study, as they indicated that frequent articulation and reception of English sounds is necessary (Lambert et al., 2017). As discussed above, little attention has been given to phonological errors in recent CF research (Lyster et al., 2013), which limits us in some ways to make comparisons and further claims. However, we could venture to recommend our delayed teacher CF strategy as a first step to explore learner preferences and attitudes towards CF of phonological errors in further CF research. In addition, practitioners or teacher researchers delivering CF could also use the CF strategy in this study to provide learners with written, more permanent versions of CF, for participants in the study by Lasagabaster and Sierra (2005) report how useful it is for learners that teachers use board-written input when they correct phonological errors. It is worth highlighting, however, that the participants in the present study do not indicate that pronouncing or listening to individual sounds or words is an efficient alternative (Tlazalo Tejeda & Basurto Santos, 2014). Despite having methods and manuals available for their reference, they prefer to be exposed to language beyond the sound or even the word level, such as the discourse present in songs or movie dialogues.

Lastly, we believe to have shed some light on the whole group vs. individual CF dichotomy, both usually given in class-fronted variations. We could claim that the CF strategy in this study offers a valid alternative for further CF research, in that it is not as harmful or face-threatening as individual correction (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012), nor as ineffective as whole group correction (Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2005; Lyster et al., 2013). “Small group” or “peer” corrective feedback, as we would like to term it, can be understood as providing teacher CF in pairs. This format aims to support students. In a pair, they share both the work and the responsibility for correction. Receiving CF of phonological errors in writing could also reinforce the idea of a shared responsibility, which should in turn encourage the development of self-regulation behaviors that pave the way for autonomous learning. We believe that the participants’ responses reveal some readiness for autonomous learning. For example, they sought and acknowledged seeking help from or interaction with peers. This behavior is promising for EFL learners in public Mexican university classrooms’. Self-awareness requires learners to step out of themselves to look at their own performance critically. Such behavior seems to be aided by interacting with peers while they prepare for their oral assignments (Picón Jácome, 2012).

Undoubtedly, this study has some limitations. Most importantly, we have to make adjustments to the delayed corrective feedback procedures in order to take full advantage of what our learners can do when asked to, when directed to, and when allowed to. In addressing RQ3 (To what extent does our feedback encourage learner self-correction and autonomy in EFL university students?), we have to admit that our correctivefeedback contributes to some extent to self-correction, but it contributes very little to explicitly encouraging learner autonomy. Some of those adjustments will have to include asking for these assignments more frequently during the course, and gradually adding corrective feedback elements that lead students to operate much more autonomously over the course of a semester. Such elements may consist of a checklist for students where they indicate what actions they performed in order to record their dialogues. Additionally, a set of action points suggested by the teacher could be included, which should ideally be later replaced by a checklist that students can create by themselves. We could eventually aspire to train learners to correct each other’s phonological errors by producing intelligible imitations (Harmer, 2006) of words or phrases with the help of available technology. For example, they could be asked to be in charge of short lists of words or phrases to correct peers based on how these are pronounced by online dictionaries, pronunciation apps or Google translator, either as a classroom exercise or as an after-class assignment.

Conclusion

In compulsory classes at beginning levels, there simply is neither the time nor the classroom conditions to monitor pronunciation adequately. Thus, a measure of learner autonomy becomes key to this effort (Buendía, 2015; Ikonen, 2013). In some Mexican EFL contexts where class size may be 40 to 50, English teachers may have to try hard to guide students to depend less and less on them (Benson & Voller, 1997; Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012). As language learners, university students may wish they have access to their language teachers as frequently as possible during lessons for a variety of reasons. Perhaps they have rarely been in contact with the English language. Or, perhaps these learners perceive English learning as inherently difficult. Producing the language orally might be particularly strenuous and demanding for students who feel apprehensive about speaking in class. Perhaps some could be offered individual tutoring outside of class in self-access centers or teacher office hours (Luna Cortes & Sánchez Lujan, 2005).

In action research, the fourth stage (the permanently forward-moving cycle) proves to be fruitful and energizing for us as teacher researchers. We have gained a student perspective (Edwards & Burns, 2016) which now helps us feel more connected to our students and their needs. We now understand that we will have to find ways to channel students’ energy to correct their own oral production as well as to help each other do so. This way, they could little by little achieve a higher degree of autonomy for language learning in general, and for oral proficiency in particular. We could venture to assume that self-correction and learner autonomy can find fertile ground on which to grow as the participants in this study show willingness to take risks and to take small steps to forward their own oral language development. Finally, we realize the need to turn teaching into a collaborative task where it is not only the teacher who facilitates learning but other people and resources in the classroom as well.

References

Baker, J. & Westrup, H. (2003). Essential speaking skills: A handbook for English language teachers. London, U.K.: Continuum.

Balçıkanlı, C, (2010). Learner autonomy in language learning: Student teachers’ beliefs. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(1), pp. 90-103. doi:10.14221/ajte.2010v35n1.8

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning. Harlow, U.K.: Longman

Benson, P. & Voller, P. (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. London, U.K.: Longman.

Beuckens, T. (2016). English language listening library online ELLLO productions. Retrieved from http://www.elllo.org/

Borg, S. & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. ELT Research Paper 12-07. British Council: University of Leeds, U.K.

Budden, J. (2008). Error correction. TeachingEnglish. British Council. Retrieved from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/error-correction

Buendía Arias, X. P. (2015) A comparison of Chinese and Colombian university EFL students regarding learner autonomy. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(1), 35-53. doi:10.15446/profile.v17n1.41821

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, N.Y.: Routledge: Taylor & Francis

Cambridge University Press. (2017). Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/es/

Council of Europe. (2001).Common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, U.K: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Edwards, E. & Burns, A. (2016). Language teacher action research: Achieving sustainability. ELT Journal, 70(1), 6-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv060

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Implicit and explicit corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2 grammar. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(2), 339-368. doi:10.1017/S0272263106060141

Fandiño Parra, Y. J. (2008). Action research on affective factors and language learning strategies: a pathway to critical reflection and teacher and learner autonomy. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 10(1), 195-210. Retrieved from http://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/10623

Frodden, C. & Cardona, G; (2001). Autonomy in foreign language teacher education. Íkala, revista de lenguaje y cultura, 6(11-12), 91-102. Retrieved from http://www.fiap.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=255025992006

Harmer, J. (2006). The practice of English language teaching. Edinburgh, U.K.: Longman.

Hernández Méndez, E., & Reyes Cruz, M. R. (2012). Teachers' perceptions about oral corrective feedback and their practice in EFL classrooms. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(2), 63-75. Retrieved from http://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/34053/40664

Hong, Y. (2004). The effect of teachers’ error feedback on international students’ self-correction ability. Unpublished Master of Arts thesis. Department of Linguistics and English Language Brigham Young University. Retrieved from http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1182&context=etd

Ikonen, A. (2013). Promotion of learner autonomy in the EFL classroom: The student’s view. Unpublished master thesis. Department of Languages English. University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved from: https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/bitstream/handle/123456789/42630/URN%3ANBN%3Afi%3Ajyu-201312102771.pdf?sequence=1

Lambert, C., Kormos, J., & Minn, D. (2017). Task repetition and second language speech processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 39(1), 167-196. doi:10.1017/S0272263116000085

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2004). A handbook for teacher research: From design to implementation. New York, New York: Open University Press

Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J. M. (2005). Error correction: Students’ versus teachers’ perceptions. Language Awareness, 14(2-3), 112-127. doi:10.1080/09658410508668828

Luna Cortes, M. & Sanchez Lujan, D. (2005) Profiles of autonomy in the field of foreign languages. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 133-140. Retrieved from: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/11189

Lyster, R., & Saito, K. (2010). Oral feedback in classroom SLA: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(2), 265-302. doi:10.1017/S0272263109990520

Lyster, R., Saito, K., & Sato, M. (2013). Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching, 46(1), 1-40. doi:10.1017/S0261444812000365

Martínez Agudo, Juan de Dios. (2013). An investigation into how EFL learners emotionally respond to teachers' oral corrective feedback. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), 265-278. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-46412013000200009&lng=en&tlng=en

McNiff, J. (2014). Writing and doing action research. London, U.K.: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Oxford, R. L. (1999). Anxiety and the Language Learner: New Insights. In J. Arnold (Ed.). Affect in language learning (pp. 58-67). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Picón Jácome, E. (2012). Promoting learner autonomy through teacher-student partnership assessment in an American high school: A cycle of action research. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(2), 145-162. Retrieved from http://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/34070

Pearson Education. (2017). Longman dictionary of contemporary English online. Retrieved from: http://www.ldoceonline.com/

Tedick, D. J. & de Gortari, B. (1998). Research on error correction and implications for classroom teaching. The Bridge: From research to practice. American Council on immersion education (ACIE) Newsletter articles online archive. The center for advanced research on language acquisition. Retrieved from http://carla.umn.edu/immersion/acie/vol1/Bridge1.3.pdf

Tlazalo Tejeda, A. C. & Basurto Santos, N. M. (2014). Pronunciation instruction and students’ practice to develop their confidence in EFL oral skills. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 151-170. doi: 10.15446/profile.v16n2.46146.

Véliz C., L. (2008). Corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Literatura y Lingüística, (19), 283-292. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35214446016

Yoshida, R. (2008). Teachers’ choice and learners’ preference of corrective feedback types. Language Awareness, 17(1), 78-93. doi:10.2167/la429.0

Zacharias, N. T. (2007) Teacher and student attitudes toward teacher feedback. RELC Journal, 38(1), 38-52. doi:10.1177/0033688206076157