Introduction

This article summarizes the challenges and issues from a 3.5-year oral homework project taking place from 2007 to early 2010 with elementary language learners at tertiary level. The overall objective of the project was to extend learner talking time outside the language classroom in groups of an average of 30 university students (Gibson 2004). Although techniques and procedures in class included pair/group work and constant interaction among learners, I still felt that there were many of these adult elementary learners who did not manage to catch up with the rhythm of the course.

This article will focus on presenting and discussing how learners at a large public university in central Mexico responded to doing oral homework in mostly off-line circumstances. It will discuss the learning benefits students perceived and what technological drawbacks they had to deal with. It is hoped that teachers who are in similar, limited circumstances find this article informative as to what they can expect out of assigning oral homework in terms of access-to-technology problems and potential learning benefits.

The project

Nowadays, there are many web pages that can help teachers extend their learners’ oral language production time. Chinnery (2005) suggests web pages where students are able to not only listen to spoken English, but to speak, listen to themselves and to classmates. I have recently started exploring and opening accounts at Voxopop (http://www.voxopop.com), Voicethread (http://voicethread.com), and English Central (http://www.englishcentral.com) to see how I can use all of these resources with my classes. It is inevitable, nevertheless, that this exploratory phase will take some time, since existing circumstances may not be ideal to run all or any of these online resources smoothly. Access to technology, which will be discussed here, could be spread out unevenly and actually be surprisingly irregular.

It was my firm conviction that a project called oral homework could still be carried out even though access to on-line resources like the ones above mentioned was pretty scarce. The overall objective of such project is to give all students equal opportunities to say something in English and to be heard. With this principle in mind, and in an effort to cater to both eager-to-participate students and extremely shy, first-time-in-an-English-class-environment learners alike, I started exploring available technology and what could be done with it.

Available technology in 2007

There is a self-access language centre on campus. However, its main use is for students to do compulsory sessions and it is therefore completely booked from 7:00 to 20:00. Since there was not a specific building for language courses, lessons were and are still taught all over the campus in the same facilities where all the other university courses are taken. These classrooms had chairs, a board and a desk, but there was no a computer available in any of the language course classrooms. Projectors or PCs, if available at each of the schools, had to be booked in advance and carried two or three buildings to the assigned language course classroom.

University facilities were in a developing stage. Some schools on campus started to have a computer room for students use. However, downloading programs was prohibited, and these computer rooms were frequently booked for other uses. A newly started, frequently unstable Wi-Fi system was available on campus and students started to bring laptops along. However, the Wi-Fi system was not available in the classrooms. The teacher-researcher could use outdated office equipment at school when available and had a telephone line connection at home. It is in these circumstances that the oral homework project started.

Using already available technologies in new ways

At the beginning of 2007, my main objective was to explore how feasible it was to ask for oral homework. In other words, the aim was to try to determine if students had access to static and/or mobile technology to record voice and produce audio files that could be later “handed-in”. It had been observed that many more students had a mobile phone than a laptop (Chinnery 2006). Most mobile phones that students took to college could play and/or record audio and/or video. Other observed devices were MP3 players and digital music players. In the absence of fully equipped classrooms, I decided to make use of the available mobile technology in the very hands of my students.

Type of recordings

In order to focus on students’ access to technology, linguistic elements of the assignment were kept simple and straightforward. For instance, students were not asked for spontaneous speech. Instead, scripted language (Cáceres and Obilinovic 2000) was chosen to lessen the challenge of handing in their recorded oral production. This scripted language consisted of short texts from course books and ELT materials for students to read aloud or role-play .

Figure 1: Sample texts for individual and pair/group recordings

Similarly, pairing up students was not fully considered for all of the assignments. Despite the benefits perceived by the teacher-researcher, it was also thought that having to meet after class could put off or at least pose some strain on university students who were very likely to have started working or already had a family. Nevertheless, since it was also believed that working closely with somebody else could be potentially helpful for learners, especially in case they had some difficulties with technology, at least one assignment that required working with peers was included in the final sets.

2007: Testing accessibility, systematizing procedures

Spring and summer terms:

Recordings were an optional assignment; doing them made up for missed written work, absences or for a maximum of 5 wrong answers in the final test (final test contains 45 questions in spring, 90 questions in summer). Recordings were distributed throughout the course, due dates were all given at the beginning of the course and strictly respected. Students handed in CDs and regular audio tapes. After informally asking students about the resources they used to prepare and hand in their assignments, it can be said that the available technology consisted of students’ mobile phones, rented PCs at nearby cybercafés and regular tape recorders.

Spring 2007

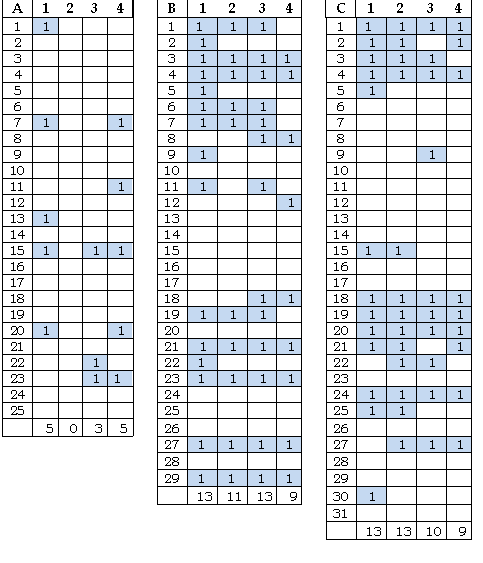

There were three groups and four recordings (three individual, one pair work) were asked for. Group A consisting of 25 students handed in assignments one, three and four. Six students did assignment 1, three did assignment 3 and five did assignment 4. Groups B and C, however, showed more interest in doing the oral assignments (see Figure 2). It is important to highlight that it was not always the same 13 or 10 students who did one or more recordings, but that delivery of recordings was distributed in the whole group. In group B, for instance, only 11 students did not do any of the four recordings.

Figure 2: Spring 2007 groups

Participation was unexpectedly enthusiastic. It could have been a result of the “great rewards” students would get out of doing the assignments, but this assumption was not enough for a good reason. In order to have a better grasp of the reasons for this phenomenon, I decided to repeat the procedures and to keep a record from students in order to understand the causes of such good response.

Summer 2007

There were two groups and three recordings (two individual, one pair work) were asked for. Delivery of recordings was distributed in the whole group in both groups A and B, both groups of 31 students. Participation, again, was unexpectedly enthusiastic: only seven people did not hand in any of the three assignments in group A whereas it was only 4 students in group B (see Figure 3).F

Figure 3: Summer 2007 groups

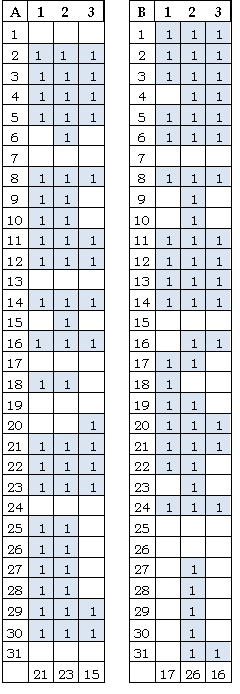

All students who handed in at least one of the recordings in the summer 2007 courses were given a short open-ended feedback page to determine the reasons they would or would not want to do recorded oral assignments in the future.

Figure 4: Sample feedback page

It was confirmed that some students did the assignments because they were interested in the rewards. However, these students also acknowledged usefulness and learning benefits in the new experience. Those students who said they would do oral assignments again gave the following reasons:

Doing it was not complicated

Those students, who thought of the exercise as something that would not necessarily be painful or extremely difficult, mentioned they did the assignments out of curiosity. They wanted to see if they were as good as they thought they were, for instance, some said “I had never heard myself, and when I did I laughed and thought, my goodness, that’s awful!” In addition, it seems that technology did not represent a major challenge to them either, and they concluded that they felt attracted by the innovative nature of the task.

Privacy

What many learners seemed to cherish most was the fact that they were able to articulate words in English privately (Tanner and Landon, 2009). There was no teacher, peer or classroom time pressure. They said and repeated sentences to themselves as many times as they felt necessary until they decided their speech was “ready to be heard.”

Self-regulation and individual effort

Learners pointed out to the fact that they were “able to hear their own mistakes and correct themselves.” An overwhelming majority said how “necessary and good for their learning” they realized it is to be aware of themselves.

Better integration with classmates

One of the elements students seemed to have enjoyed the most was the fact that they helped each other when they worked in the pair-tailored assignment.

Fall 2007

Three colleagues at the same university were invited to participate with their groups to do 1 or 2 oral assignments. A total of 13 groups handed in one, two or four oral assignments. Available technology still consisted of mainly learners’ own mobile phones, rented and personal PCs, personal laptops and other handheld technology such as iPods and MP3 players. Teacher-researcher could still use outdated office equipment at school when available and functioning and had a telephone line connection at home.

Recordings for students of invited teachers were all pair-work format. Participation increased substantially as it can be seen in Figure 3. It is important to highlight that participation in invited groups was completely out of learners’ own initiative and that learners worked out ways to hand in assignments in different formats such as their own MP3 players, files via Bluetooth, voice recording options in power point software, etc.

Figure 5: Sample of Fall 2007 groups

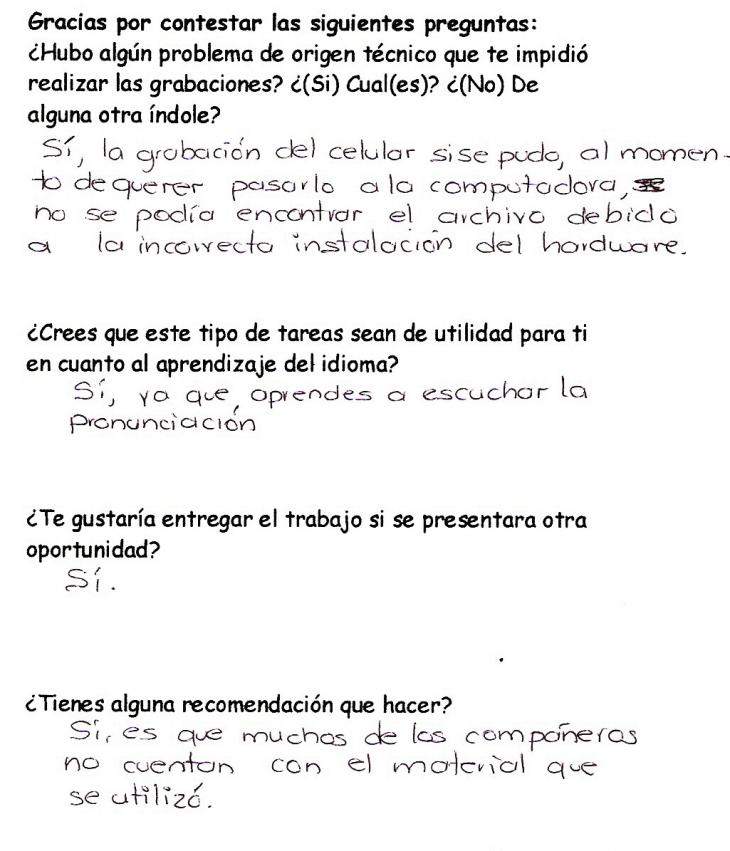

Learners were asked to answer an open-ended questionnaire. Some of these learners were also asked to participate in group interviews/focus groups to learn about the technical problems they faced when producing their recordings and what learning benefits they could perceive in doing these.

Open ended questionnaires

The reasons learners who did not do assignments gave for not having done them were mainly technology related. Students may have a laptop but no internet connection at home, or may not have a computer at all. Students who did the assignments were classified in those who said they did not have technical problems and those who did. Those who did not have technical problems seemed to describe themselves as technologically skilful or updated. They acknowledged there are classmates who do not have access to as many resources as they do. Students who said they had technology related problems seemed to suggest they did not have regular access to technology (e.g. they use internet sporadically or for short periods of time either at school or in cybercafés). They also explain that there are unknown formats and that they are not familiar with programs or with their recently bought equipment/software.

Figure 6: Reasons for not having done the assignment

Figure 7: Problems faced to hand in assignment

Group interviews

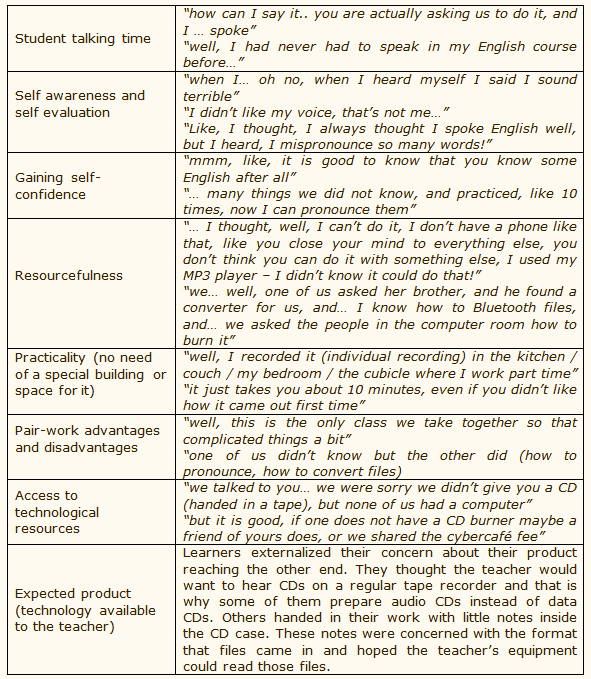

A total of 4 group interviews were carried out, one with 12 students, a second one with 10 (14 and 10 minutes) and two 8-to-10-minute more with 4 students each. Learners’ response to oral assignments in these group interviews was mainly concerned with expanding the answers students gave in the questionnaires and resulted in the following topic areas:

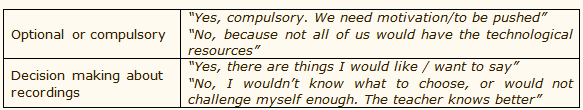

Questionnaires and group interviews

Both instruments also gave information as to whether students could be asked to do this exercise as part of their course assignments and whether they would like to participate in the decision making about the characteristics of recordings.

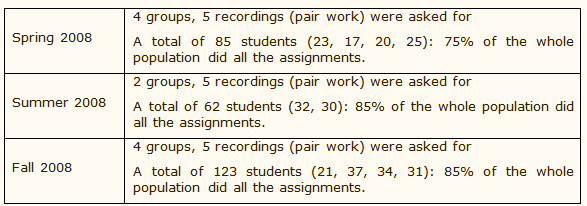

2008: Proved accessibility, systematized procedures

Having confirmed that the majority of students had the means or were able to work out ways to do the assignments, the focus at the beginning of 2008 was to promote interaction and shared resourcefulness among learners. Therefore, recordings were no longer an optional assignment, and they counted for a 10% of final grade. A total of five pair-tailored recordings were distributed throughout the course, a calendar of due dates was given on the first day of classes and it was strictly followed. Pair-work to be recorded consisted of conversations from learners’ textbooks, role-play conversations and something of their choice.

Available technology still consisted of mainly learners’ own mobile phones, rented and/or personal PCs, personal laptops and other handheld technology such as iPods and MP3 players. Students heavily relied on each other for the technology and linguistic issues of the assignment. Assignments were also accepted in USBs, but viruses were a major problem with this type of media. Teacher-researcher still used outdated office equipment with a high speed connection at school when available and had a telephone line connection at home. Some learners tried sending their audio files via email so I had to make room to use school equipment more often.

According to students, the advantages of sending audio files via email were: (1) they do not have to buy CDs, and (2) uploading AMR files is easy as these are less heavy than MP3 and other audio file formats. Uploading on campus was not a good option yet, for the Wi-Fi system was still pretty unstable. Computer rooms’ rules are strict about allowing students access to their personal email addresses. Uploading is mostly done from nearby cybercafés or, in a very few cases, from students’ high speed connections at home.

At the end of the year, learner participation in decision making and feedback for recordings were carefully looked at since peer evaluation and/or feedback started to be considered in the plans for 2009.

Avoiding pair-work

A curious learner response was the case of those students who figured out ways not to interact together or not to meet at all and still hand in their pair work assignments. In one of the cases, the two students were observed to have agreed to meet sometime before or after class to do the assignment. One of them brought his laptop, where his partner would record all of her lines, making a short pause between them. She would then go to class and he would start recording his lines following the same procedure. In his laptop, he had a program which allowed him to mix and edit audio recordings – it allowed him to cut a single recording into pieces, and to insert pieces from another recording. They were never approached to know exactly which program they used or to be asked to really interact together. Instead, I decided not to intervene and let the phenomenon flow.

Earlier in the year, another pair of students did something similar: each of them recorded their lines separately and kept these individual lines in very small, a-few-seconds long Real One Player files (MP3 files). Then one of them put all these tiny files together on a single CD. The small files were numbered so that the teacher would know which one to click on first, which in fact, resulted in the conversation that was asked for. While the first pair of students figured out how to avoid interaction, the second one found out ways not to meet at all and still do the task.

Although at first it was a bit disappointing to see that students were not working together as the rest of them were, no intervention whatsoever to prevent it from happening was taken. The reason for not taking action was that it seemed to be an important aspect of learner response to doing this type of assignment – a likely scenario. This experience helped me unveil the beliefs and ideas I had about having learners do this type of task. For me, I realized, it was important they met and interacted in a pair-tailored exercise. It became very clear to me that I had to make interaction between learners explicit, or perhaps try to make it more difficult for them not to meet. Thus, this type of learner response had an effect on my planning.

2009: Proved accessibility, learner participation in decision making.

Very similar to the 2008 stage, the focus of this phase of the project was to promote interaction and shared resourcefulness among learners. Also, peer evaluation and/or feedback started to be considered. At the end of the Summer and Fall courses, students were asked to write about what it was for them to work with technology for their assignments. These short accounts were written in English as students said they were comfortable with it.

Recordings were no longer an optional assignment, and they counted for a 10% of final grade. A total of five pair-tailored recordings were distributed throughout the course and a calendar of due dates was given on the first day of classes. This calendar was strictly followed. Pair-work to be recorded consisted on conversations from learners’ textbooks, role-played conversations and options to choose from. Freedom to choose what to record was extended to other options learners later in the course suggested: reading a poem together, singing a song together, and writing up their own stories.

Available technology still consisted of mainly learners’ own mobile phones, rented and/or personal PCs, personal laptops and other handheld technology such as iPods and MP3 players. The Wi-Fi was much more stable, so several more learners had access to better bandwidth on campus. Some more students also had high speed connections at home, and so did the teacher-researcher towards the second half of the year. Students still relied on each other for technology, as samples from the reflections they wrote at the end of the course show:

“using technology was fun and interesting… I believe technology offers a wide variety of resources with a low cost which is very important for students in public universities like us”

“we had technology that was a challenge for me because I am not good at it. I thought “how I am supposed to do it” but I have to admit that my boyfriend helped me to convert the first recording… And I learned how to do it but as I do not have a burner in my computer my friend did it for me.”

“perhaps it was kind of late when I understood how things worked in this technology environment, anyways I hope I can further use some of the things I learned about technology”

“I tried to buy a recording cassette player, however nowadays it does not record any cassette, this not exist anymore only plays the cassette! (really I felt devastate, because in that moment I felt that I was the older or the elder, elder, elder in your class)”

“So first, I learnt to use my husband’s palm, after that the cell phone recording, and finally I could to bring you my last recording in CD. Yes, as you can imagine this, I had to ask to many, many persons in order to investigate how I could do my voice recording in CD. [Taken from learners' written reflections at the end of the course.]

Creative work

Although there were always one or two assignments that went beyond just recording voices and incorporating creative elements such as background music, it was not until 2009 that learners’ creativity boosted in several other examples. For instance, a couple of students from architecture and design studies wanted to sketch their version of a conversation they had to role-play. They handed in power point slides and inserted audio with their own voices instead of speech bubbles. Another pair of students from social studies chose to read Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous speech out loud and incorporated background applause to it. At the end of 2009, it was decided that having students listen to each other’s creative work and react to it would be a natural step to take for the year to come.

Figure 8: Sketched version of assigned conversation

2010: Learner participation in decision making and evaluation processes.

The focus of this year was to encourage learner involvement in decision making and evaluation processes via systematic group interaction and empathy from the very beginning (Shumin 1997). Since evaluation / assessment are quite a vast field, this section will be looked at as the beginning of another project. Learner response to oral homework here is concerned with how they dealt with getting feedback on their recordings, and giving feedback to other student’s recordings. More than asking learners to grade their peers’ work, they were asked to react to it as they would in listening exercises. They were asked to listen and to answer questions such as:

Did you get the joke?

Was their plan better organized than yours?

How long did the trip take?

A couple ofsessions later, they took home other people’s work to mark with evaluation sheets. At the end of the course, they were asked to write a short reflection about what it was like to have had oral homework that peers and teacher gave feedback on in the course. Most students were comfortable with writing these short reflections English. A few samples of learners’ reflections, as they wrote them, are reproduced here:

"The Evaluations were helpful because when I recorded I did not realize of some aspects that I needed to improve because of nervousness and in that way my partners’ comments helped me... I liked this part of the course”

"The bad thing is that some of the evaluations I received were so hard. Sometimes I got comments that made me feel so bad with myself. Some of them had reason but others were so exaggerated.”

“In my point of view, one of the main factors of this subject was to give and receive feedback of our recordings. In this way we perceive our strengths and weaknesses we did not realize at the moment of recording.”

“We can make observations to others in order to improve… Finally, something which is important for me when evaluating the performance of students is the effort they make to get a good job.” [Taken from learners’ written reflections at the end of the course.]

From analyzing all the reflections, it can be said that learners did not feel very comfortable at the beginning and approached the evaluation with suspicion and fear. Little by little, however, they felt more relaxed, safer and willing to receive criticism from their peers.

Summarizing learners’ response

Oral homework was found to be attractive; different from everything else students had done before in language learning. The fact that they were encouraged to use their mobile phones for an assignment (Chinnery 2006) intimes when these were indeed being banned from classrooms (Diario EL PAÍS 2007) is a factor that could have well contributed to their curiosity. Reasons for not doing it, either when it was an optional assignment or when it was compulsory, may well relate to, as many learners expressed, access to technology. However, there could be other sources of resistance such as beliefs about language, about learning and/or personality traits (Littlewood 2001).

It has to be acknowledged that while some learners may be completely wired; there will always be a good number of them who may not be as connected as assumed (Thelmadatter 2008). They may in fact be economically or geographically unable to be on-line on a regular basis. These circumstances require planning that caters for average connectivity (Egbert 2005) so that less wired learners are not excluded from the learning experience. Similarly, teachers may not be as connected as they “should be.” It is a very common case that, being digital natives (Prensky 2009), learners are much more likely to be familiar with those technologies that teachers are little by little digesting. Moreover, teachers may not even feel the need to increase their connectivity status and remain pretty much off-line.

In cases where learners are, in their own words, not very good with technology, it also has to be acknowledged that many people can take only one thing at a time. Otherwise, this turns people against the assignment due to technology-related frustration. Moreover, the fact that technological resources (e.g. computer rooms, free Wi-Fi) tend to become available rather slowly may also contribute to putting learners off trying.

Concluding Insights

As a whole, it could be said that learners responded fairly positively to oral homework. Possible reasons could include curiosity and feeling challenged to try something they were familiar with but in a different way. While newness may have been one of the most powerful factors to make them feel attracted to the task, it meant, however, that as their teacher, what I was asking them to do was also new to me. Early in the project, I realized I would have to be very flexible with my controlling the task – I constantly asked learners for their help, especially how they overcame minor problems with technology. I was lucky to have very helpful learners.

When working on the assignments, many learners expressed that they had to be patient with themselves and others to make effective use of whatever resources they had. Some students had to ask for help from other people in their household, others went to “more experienced” peers, and a few more came to me. Working with others as a way to develop resourcefulness increases the potential benefits of having oral homework in a language course, both for learners and teachers. Oral homework can indeed be a very attractive option to help learners and teachers to learn together.

Finally, exploring what your available resources are and the flexibility that is needed from the teacher and the students may be a phase that cannot be skipped. It may be a good idea to start small and keep focused. For example, if you just learned how to attach or download audio files to and from emails, keep doing it until you feel you manage it. If you are not the kind of person who can easily incorporate something new without feeling overwhelmed, do not force yourself to absorb technology all at once. Technology is an ever-changing entity. However, teachers and learners could share what they have learned when solving minor problems and teach and learn from each other. In other words, embarking in an oral homework project could be the ideal scenario to start and keep exploring technology together.

References

Cáceres, L. I., and K. Obilinovic. 2000. The Script-based Approach: Early Oral Production in Language Teaching. English Teaching Forum 38 (4): 16-19 http://eca.state.gov/forum/vols/vol38/no4/p16.htm (accessed November 9, 2009)

Chinnery, G. M. 2005. Speaking and listening online: A survey of internet resources. English Teaching Forum 43 (3): 10-17 http://exchanges.state.gov/englishteaching/forum/archives/2005/05-43-3.html (accessed October 18, 2010)

Chinnery, G. M. 2006. Going to the MALL: Mobile Assisted Language Learning. Language Learning and Technology 10 (1): 9-16. http://llt.msu.edu/vol10num1/emerging/default.html (accessed October 18, 2010)

Diario EL PAÍS S.L2007. Una región de India estudia prohibir el móvil a los menores de 16 años. EFE - Nueva Delhi - 12/09/2007 ©.

Egbert, J. 2005. CALL essentials: Principles and Practice in CALL classrooms. Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. TESOL

Gibson, G. 2004. Facilitating English Conversation Development in Large Classrooms. The Internet TESL Journal 10 (9, September). http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Gibson-Conversation.html (accessed October 14, 2009)

Littlewood, W. 2001. Students’ attitudes to classroom English learning: A cross-cultural study. Language Teaching Research 5 (1): 3-28

Prensky, M. 2009. H. sapiens digital: From digital immigrants and digital natives to digital wisdom. Innovate 5 (3). http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=705 (accessed April 17, 2009)

Shumin, K. 1997. Developing Adult EFL Students' Speaking Abilities: Factors to Consider. English Teaching Forum 35 (3, July-September): 8-13. http://eca.state.gov/forum/vols/vol35/no3/p8.htm (accessed November 9, 2009)

Tanner, M. W. and M. M. Landon. 2009. The effects of computer-assisted pronunciation readings on ESL learners’ use of pausing, stress, intonation, and overall comprehensibility. Language Learning & Technology 13 (3, October): 51–65 http://llt.msu.edu/vol13num3/tannerlandon.pdf (accessed October 1, 2009)

Thelmadatter, L. 2008. Becoming part of a “community” online in order to acquire language skills. MEXTESOL Journal32 (1): 47-68.