Elizabeth is a novice English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teacher in a metropolitan area of Mexico. She recently graduated from a very good teacher education program where her professors went to great lengths to help her become a good teacher. In all of her classes they made a distinction between two aspects of teacher education: teacher training and teacher development (Richards and Farrell 2005).Teacher training refers to teacher learning focused on a teachers immediate goals. Teacher development activities are related to overall professional growth. These activities are more related to long term goals. Teacher development is what Elizabeth is concerned with at this point in her teaching career.

As she had been an excellent student, she was concerned with being an excellent teacher. But, still, she was unsure of how she could do that. She knew that the most recent ideas surrounding teacher education (Shulman 1986, Richards 1998) were based on what teachers must know. Shulman introduced the concept of teacher knowledge by proposing three areas of knowledge which including content area knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and curricular knowledge. Richards (1998) was more specific to Elizabeth’s area of EFL; he proposed the following six domains or areas of knowledge that teachers must possess.

Figure 1: Six Domains of Knowledge that a Teacher Must Possess

Another concept that her professors always emphasized in her teacher education courses was the importance of reflective teaching. Based on the work of Schön (1983) educators around the world began to realize that it was important to reflect on what one does in the classroom in order to improve one’s practice. For Elizabeth, Bartlett’s (1990) reflective cycle resonated with her views of teaching. Bartlett’s concept consists of five stages of reflection. The first stage, mapping involves examining the teaching episodes or asking what one did as a language teacher. In the informing phase the teacher seeks meaning, reasons, or principles related to what had happened in the mapping stage. The contesting stage of the cycle allows the teacher to reflect on the actual happening and ways in which the teaching experience could have been better. This examination of the teacher practice and how it could improve leads to the appraisal phase. The final or appraisal stage involves the implementation of the teacher’s re-constructed ideas about her practice. Bartlett advocates a continuous application of the reflective cycle to teaching.

Elizabeth had created teaching portfolios as part of her teacher education program and while she was creating them they were instrumental in helping her to examine her reflective practice. However, now that she is an in-service teacher, she has discontinued her reflective practices. She feels guilty when she takes time from her lesson planning and material development to contemplate what she has done in the classroom. Moreover, she is bothered by the excessive use of paper and ink to create portfolios in binders that end up in her car trunk or under her bed. She has decided she must find a more efficient and collaborative manner of implementing her reflective practice.

She has decided that she needs to be collaborative in her reflective practice because recently she has read about theories of social learning or Sociocultural Theory (SCT) as she has heard it referred to by prominent language learning theorists and teacher educators (Johnson 2009; Lantolf & Thorne 2006; Lantolf 2000). She likes how this manner of looking at language learning, which finds it roots in Vygotskyan cognitive psychology, views social context as the most important factor in individual transformation and development. The idea that it is through social interaction that mental processes become controlled entirely by the learner and that higher order thinking skills are developed resonates with her thinking.

In her reading about SCT, she has come to understand that when one adopts a social view of learning, one accepts the belief that development occurs first intermentally and is next internalized intramentally. One theorist, Valsiner (1987) explains this phenomenon when he states development appears “first in the social, later in the psychological, first in relations between people as an intrapsychological category, afterwards within the child as an intrapsychological category” (p. 67). Elizabeth understands that in this theoretical approach, knowledge is not static waiting to be transmitted to an individual; instead it is fluid, created in the social milieu and a product of shared interaction.

Elizabeth’s reading and understanding has brought her to the conclusion that the two most well-known concepts born out of Vygotskyan theory are scaffolding and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). She was also surprised to find out that the notion of scaffolding finds its roots in the work of Wood, Bruner and Ross (1976). She had always attributed the ZPD to Vygotsky, but they put forth scaffolding as an instructional strategy by which the teacher provides only the assistance that is necessary for a student to complete a task. In Elizabeth’s own words, the teacher provides assistance that is contingent on the needs of the learner.

There is other research that Elizabeth has read about. For example, Aljaarfreh and Lantolf (1994) established guidelines for providing assistance, or mediation in the ZPD. She understood that their work is based on Vygotskyan theory and that their suggestions mirror the best practices of scaffolding. Her understanding of their work also points to the fact that the, assistance that a teacher provides to a learner should be contingent on the learner’s needs and feedback should never be too explicit. In her own classroom, Elizabeth could see how this would allow the learners to reach the correct answer or conclusion on their own.

When reading Vygotsky’s original work, Elizabeth understood the ZPD to be “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky 1978, p. 86). As a result, she could easily see how the ZPD plays an integral part in understanding how to provide instruction that is properly scaffolded. As a novice teacher, Elizabeth is concerned with providing scaffolding in the manner that will most benefit a learner, she has learned that she be aware of two developmental components; actual and potential development. In the theoretical explanations, actual development is what a student can do autonomously or without assistance; potential development is what a student can do with the help of a more capable peer. The ZPD offers novice teachers such as Elizabeth a description of a learner, taking into account their actual and potential development. As she acquires a more robust understanding of the ZPDs of each of her students Elizabeth will scaffold classroom and individual interactions.

As she works to understand the factors that play out in her classroom, Elizabeth remembers Richards’ (2001) domains second language teaching. In her reflective practice, she would like to contemplate second language learning theories as well her pedagogical practice.

In her search for a more efficient manner to become more collaboratively reflective, Elizabeth has wanted to try to implement new technological tools that are available to her via the Internet. Although she is not considered ‘techy’ she thinks she could apply the tools she has heard described as Web 2.0 tools. As in most parts of Mexico, she has access to the Internet at school and on her desktop computer at home. She uses email regularly with her students to remind them of assignments and mediate their understanding of particular concepts. As a result, she is interested in learning how she could use collaborative Internet tools to augment her reflective practice.

Here is a description of the information that Elizabeth found when she began to investigate Web 2.0 technologies. She has found that the term web 2.0 is used to describe a number of Internet based applications that are in some manner different from Internet based applications from the web 1.0 era. Generally, web 2.0 technologies have a focus on the social and collaborative use of technology. Although she has heard of these tools, she was never aware that some of the most canonical examples of these technologies are blogs and wikis.

In her life, Elizabeth has used Web 2.0 technologies to promote the understanding that the way that we view the world and she understands that the knowledge that we derive from it is jointly constructed. Elizabeth understands the difference between these technologies that can be contrasted with more traditional technologies that promote the one-way transmission of knowledge, or the view that knowledge is something that is transferred to a student through a teacher. Basically, Elizabeth understands that Web 2.0 technologies can be said to represent a socially constructed view of knowledge and learning, while web 1.0 technologies can be said to represent a more binary or Cartesian view of knowledge and learning.

In her reading, Elizabeth also discovered that the term web 2.0 is relatively new one. It was first used to describe the evolution of Internet technologies from distributers of knowledge to vehicles of interactivity. She read that DiNucci (1999), when describing web 2.0 stated “The Web will be understood, not as screenfuls of text and graphics but as a transport mechanism, the ether through which interactivity happens”. Web 2.0 technologies facilitate interaction and web 1.0 technologies transmit knowledge.

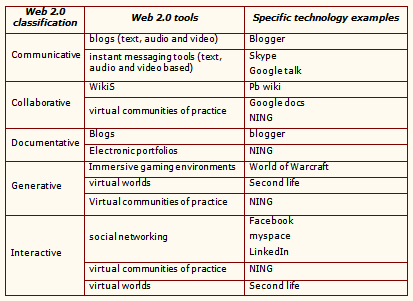

Elizabeth was surprised to discover that there is a myriad of tools available that can be said to belong to web 2.0, there are many options for her to use. But it seems like every day there are some new Web 2.0 tools. As a result, attempts to codify them will soon be antiquated. Elizabeth was happy when she found that in response to this challenge McGee and Diaz (2007) attempt to delimit and more precisely define web 2.0 technologies by providing a five-part classification scheme. Their scheme groups technologies according to their function. They emphasize that as with all web 2.0 technologies, interactivity is at the core of their use and are at the same time consider to be communicative, collaborative, documentaries, generative and interactive. She read a brief discussion of these technology types and has tried to understand the differences between each tool. .

Here are the ways that the tools were explained by McGee and Diaz (2007) The function of a communicative technology is to facilitate communication among person or groups. More specifically, she found that they are tasked with finding ways “to share ideas, information and creations” (McGee and Diaz 2007, p. 4). Examples of communicative technologies would be blogs (text, audio and video), and instant messaging tools (textual, audio and video based).

The second category that Elizabeth read about was a collaborative technology which is used to jointly with another individual or group of individuals. She understood that, a collaborative technology is used “to work with others for a specific purpose in a shared work area” (McGee and Diaz 2007 p. 4). The examples that she found for collaborative technologies would be wikis and virtual communities of practice.

Elizabeth understood that a documentative technology is a one that documents information with the aim of sharing it with others. She felt strongly that since the purpose of these technologies is “to collect and/or present evidence of experiences, thinking over time, productions, etc” (McGee and Diaz 2007, p. 4) she would like to include this technology in her repertoire. Examples of these technologies include blogs (text, audio and video), as well as electronic portfolios.

Generative technologies are those that generate something that is otherwise inaccessible in a real world context. It was easy for Elizabeth to understand this concept because her students were always asking her about new words they found online or in the video games they play. She had already read McGee and Diaz’s definition of a generative technology as one that is used “to create something that can be seen and/or used by others” (p. 4). Most the examples they offered, such as immersive gaming environments, virtual worlds, and virtual communities of practice she had either seen herself, or her students had described for her.

The last category that Elizabeth read about was the interactive technologies that provide users with the opportunity to collaborate with other individuals. In McGee and Diaz’s (2007) words, they exist in order “to exchange information, ideas, resources and materials” (p. 4). She already had a Facebook page, which is an example of an interactive technology; these technologies include social networking, virtual communities of practice and virtual worlds. To help her further understand the concepts, Elizabeth created the following table (see Appendix A), which she adapted from McGee and Diaz, 2007.

Figure 2: Web 2.0 Technologies and Classification

After Elizabeth had finished her research into Web 2.0 tools for reflective practice, she had to consider which tools she would use for different phases of Bartlett’s reflective cycle. In addition, she had to begin to think about how she would invite collaboration from her peers or other teachers she knew. Her first task at hand was to think of ways to apply the technological tools to the creation of her reflective community of practice.

She realized that her first step would be to create a site that could store documents, video, audio, and text that could be accessed collaboratively by her colleagues. As this would be a virtual community of practice, she decided to create a NING. At its inception in 2004, NING was a free Web 2.0 tool that has been used by a myriad of individuals and groups to network socially via the Internet. However at the time that this article was written this is no longer the case. Presently creators must pay hosting of a NING community.

The better understand how she could network with and benefit from her peers, Elizabeth wanted to understand more fully the concept of a Community of Practice (CoP). She found Wenger, McDermott and Snyder’s (2002) work where they outline the concept. They define a community of practice as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area on an ongoing basis (p.4). This is just what she wanted to do; interact, learn with and from her EFL teaching peers in Mexico and abroad.

As she read more she began to learn about the parts of a community of practice, she found Wenger (1998) where he discusses the three elements that should be present in a CoP. First is domain or the topic that the CoP is centered around. Second is community or the social cohesion that binds the group members together. The last element is practice, or the collaboratively created artifacts and shared resources that the CoP has created over time.

Elizabeth knew that she could create the domain by targeting her NING to EFL teachers who were interested in ongoing professional development. These teachers would be her audience and at the same time give them a shared interest that would build bind the group together. Elizabeth examined the tools that could be included in the NING and discovered that as the group owner she could deter mine the appearance and features that her NING would have. She also learned that she could later add feature if she wanted to increase the functionality of the group. Initially she created a collaboration, media and events space to be included on the toolbar on her main page. These spaces would house the tools that would be displayed on the main page of the community page. She realized that she would have to spend more time designing and organizing the available spaces. She based her decisions on what she thought the group would like to use to share ideas and interact through this Web 2.0 tool. Here is a more complete description of each space that Elizabeth decided to include in her social networking space.

Main page

The main page displays all of the Web 2.0 tools available to members. It shows the same tools that are embedded in a tool bar that is at the top of the main page. The main page also can include an introductory statement or welcome that offers a description of the community and explains how to join or become a member. In this way the main page can be used to create the domain aspect of a CoP. That is to say, the topic and purpose would be clearly displayed on the main page.

Discussion forum

The discussion forum will be used as a space where the participating teachers can discuss their practice and use writing as a means of reflection on what they planned, what they did, and the resulting events in the classroom. They will be able to share their thoughts with the other members of the community and comment on what has been published by other teachers. The use of the discussion board will help to build the community aspect of the CoP by helping to create ties that bind the group members together. Additionally it provides a space for the creation of shared artifacts and resources. In this way, the discussion board contributes to the practice aspect of a CoP.

Members page

The members page shows the members’ names and displays a photo if they provided one when they joined. When one clicks on the member profile, it links to the member’s page. It also links the individual member’s most recent activity on NING. The member page aspect of NING helps to create the domain and community aspects of a CoP by clarifying each group members’ interests and providing a manner to directly interact with them.

Sub-groups

Within the sub-group space members can provide links to other groups that would be of interest to the member s of the community. In addition, the members of this NING can create groups. For example, if a small group of teachers worked at a particular school, they could form a sub-group for t heir school. Another example would be a sub-group related to a particular interest, such as teaching EFL in primary schools. Sub groups help to create the practice element that must be present in a community of practice by providing a space, in much the same way that discussion boards do, for the shared creation of artifacts.

Media

The media space allows community members to share media-based information. For example, if one of the group members wanted to video record her classroom practice and request feedback from the community of practice the video could be uploaded to the NING. If the video is too large to upload to the NING, another option would be to upload it to YouTube and provide the link via the NING. YouTube in one of the applications included as a design feature on NING. The media space of NING is useful in establishing the practice element of a CoP because it provides a repository for materials that can be used in EFL teaching.

Events

Finally, the events tab allows members to post information about events in their prevue. For example, news about upcoming conferences and calls for participation in the events could be posted in this space. When used in this manner, the events element of NING creates the community aspect of a CoP by providing opportunities for members to interact outside of the virtual group.

As soon as Elizabeth finished designing her NING, she became very excited about using it. She began to talk to her colleagues and asked them to participate. She soon realized that she did not need to restrict participation to people in her immediate geography area. She therefore began to think of ways to invite people into her virtual community of practice on a larger scale. She spoke with colleagues at conferences, both national and international, and asked them to suggest people who would like to join. However, for the moment, she would begin with her colleagues at school and from her educational experience. At any rate, she had set the membership so that she would have to approve anyone who wanted to join the community, as this is one of the security features that NING provides.

Conclusion

Elizabeth’s story allows us to reflect on how an electronic, Web 2.0 community of practice can be created to mediate professional development. We were able to understand how social learning theories facilitated Elizabeth’s understanding of interaction and collaboration in such a community. Finally, her hands on experience with creating the NING gave her a real feeling of how it worked and how it could be a community of practice.

References

Aljaafreh, A., & Lantolf, J. P. (1994). Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal, 78(4) 465-483.

Bartlett, L. (1990). Teacher development through reflective teaching. In J. C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 202-214). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

DiNucci, D. (1999). Fragmented future. Print, 53(4), 32, 221-222.

Johnson, K.E. (2009). Second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective. New York: Routledge.

Lantolf, J. P. (Ed.)(2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of L2 development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McGee, P., & Diaz, V. (2007). Wikis and podcasts and blogs! Oh my! What is a faculty member to do? EDUCAUSE Review, 42(5), 1-11.

Richards, J. C. (1998). Beyond training: perspectives on language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schön , D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. London: Temple Smith.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Valsiner, J. (1987). Culture and the development of children's action: A cultural-historical theory of the developmental psychology. Chichester: Wiley.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practices: Learning as a social system. System Thinker, 9(5), 1-10.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W.M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.