Introduction

In the past two decades, second language (L2) creative writing has gradually gained some momentum in the field of second and foreign language teaching and learning. Empirical studies have shown that engaging language learners in L2 creative writing tasks can develop L2 literacy, writer identity, and motivation (Banegas et al., 2020; Canagarajah, 2020; Hanauer, 2010; Disney, 2014; Maguire & Graves, 2001; Yang 2018; Zhao, 2015). These positive effects make L2 creative writing an important supplement, if not a correction, to a widespread ‘banking’ model of literacy education (Freire, 1970) in an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context that emphasizes forms over meaning and conventions over creativity (Hong & White, 2012). In the case of student-teachers in Argentina, Banegas et al. (2020) suggest that the authenticity of L2 creative writing tasks, as achieved through the pedagogical design of “writing for publication,” may motivate and engage learners, and consequently create a space for learners’ language use and development (p. 35). While L2 creative writing has generally been applauded by researchers (e.g., Arshavskaya, 2015; Babaee, 2015; Kim, 2018), few have examined the teacher’s theoretical orientations, such as world Englishes, in teaching creative writing and the extent to which stated goals in the creative curriculum are fulfilled, especially when the course is taught by English native-speaking (NS) creative writing teachers.

In line with earlier studies, which treat writing as a situated social practice (Hyland, 2016; Ivanič, 1998), the present study addressed these research gaps by focusing on a specific EFL creative writing course taught by an NS creative writing teacher. By paying close attention to the goals, materials and assessments employed, underlying theories used to support pedagogical decisions, reflections of the teacher and the students, and the ways of evaluating the students’ performance, the present study sought to provide an insight to an actual EFL creative writing class. This case study provides useful knowledge for other creative writing teachers to reflect on their teaching practice. It may also provide researchers of EFL creative writing with a useful reference for conducting similar research and building on the findings of this study.

Literature Review

According to Alen Malley, a forerunner in creative writing for L2 professionals, creative writing can be broadly defined as any writing that emphasizes an “aesthetic and affective” appeal instead of some “pragmatic” functions (cf., Babaee, 2015, p. 1). In the present study, diverse genres featuring creative expressions of human experience, emotions, and imagination such as poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction (Earnshaw, 2007) are regarded as examples of creative writing.

The past two decades have witnessed a growing interest in L2 creative writing around the world (Dai, 2010; Disney, 2014; Hanauer, 2010; Kim, 2018; Kim & Park, 2020; Zhao, 2015). Several writing teachers have explored creative writing in their institutions with L2 learners to encourage “writing improvement, language play and an escape from the pseudo-narratives of the textbook” (Zhao, 2015, p. 2). In North America, the use of poetry with international graduate students was spearheaded by Hanauer (2010, 2012), who advocated a pedagogy of meaningful literacy by linking writing with students’ lives and emotions. Moreover, bilingual educators have designed writing tasks that feature language learners’ life stories, sometimes as mediated by modern technologies (Edelsky, 2003; Maguire & Graces, 2001; Skinner & Hagood, 2008), exemplifying the pedagogy of creating and sharing multilingual writers’ “identity texts,” or texts that magnify their sense of self in positive ways (Cummins & Early, 2011, p.3). Similarly, creative writing has also been promoted in diverse EFL contexts such as those found in Asia (e.g., Iida, 2010), the Middle East (e.g., Hassall, 2006, 2011), and Africa (e.g., Pfeiffer & Sivasubramaniam, 2016). In Asia, Iida (2010, 2012, 2016, 2017) taught Haiku, a kind of Japanese poem with three lines that contain 5-7-5 syllables, to his EFL college students in Japan. Hassall (2006, 2011) and his colleagues in the United Arab Emirates hosted Extremely Short Story Contests (ESSC) where EFL learners wrote stories containing exactly 50 words. In China, many scholars (Dai, 2010; Hong & White, 2012; Li, 2015; Yang, 2013, 2020) have reported their innovative ways of teaching life writing, a broad term that includes many different genres of personal narrative, in their respective universities. This burgeoning literature foregrounds the agency of teachers in L2 creative writing courses.

Furthermore, existing literature highlights multiple benefits of L2 creative writing for language learners. Hanauer (2010) found that poetry writing helped his graduate-level English as a second language (ESL) students to express their emotions concisely and artistically. A similar result was reported with EFL learners by Iida (2011) who found teaching his Japanese university students to write Haiku helped them to develop L2 literacy, explore life experiences (Iida, 2016), and develop unique voices (Iida, 2010, 2017). L2 poetry, as generated by students, has also been used as a research method (Hanauer, 2012) to elicit Chinese university students’ understandings about Chinese culture and history. Additionally, creative writing, in the form of alternate perspective-taking (e.g., “from the perspective of a young Saudi woman”) (Arshavskaya, 2015, p. 77) and “writing for publication” (Banegas, et al., 2020, p. 29), was found to motivate L2 learners to engage in literacy activities. Last, learners’ engagement in L2 creative writing was also found to increase learners’ confidence and agency (Yang, 2013, 2020; Zhao, 2011, 2015; Zhao & Brown, 2014). These studies suggest that L2 creative writing is a viable pedagogical option for language learners.

The growing interest in L2 creative writing can be attributed partially to two paradigm shifts in teachers’ language ideology. One paradigm links language learning closely to learners’ identity work associated with their language learning and use (Darvin & Norton, 2015; Hanauer, 2012; Ivanič, 1998; Kramsch, 2009; Li, 2007; Norton, 2000; Yang, 2013; Zhao, 2015). Hanauer (2012), who proposed a meaningful approach to second and foreign language literacy education, for instance, argued that “[u]ltimately, learning a language is about widening one’s expressive resources and positioning oneself in the multicultural and multilingual world” (p. 114). An engagement in L2 literacy requires developing an understanding of one’s established sense of self in the first language and culture while exploring new possibilities in another, thus “transcribing selfhood into a new linguistic materiality” (Disney, 2014, p. 4). Accordingly, Hanauer (2012) and his former PhD students (e.g., Iida, 2016) advocated poem writing as a pedagogy to centralize the experiences and emotions of their language learners. The other paradigm adopts a critical perspective on the non-native varieties of English, such as world Englishes (Canagarajah, 2006; Disney, 2014; Hassall, 2006; Lim, 2015), translingualism (Canagarajah, 2011; Kim, 2019; Liao, 2018), transliteracy (You, 2016), and translanguaging (Darvin, 2019; García & Wei, 2014). Despite their nuanced differences, these perspectives treat L2 learners’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds as a “resource” rather than interference in L2 literacy activities. Translingualism, for example, is defined by Canagarajah (2020) as “an orientation to communication and competence that treats words as always in contact with diverse semiotic resources and constantly generating new grammars and meanings out of this synergy” (p. 6). Hence, ‘accents’ in writing such as non-standard use of English and the embedded use of non-English languages are understood as a positive display of multilingual writers’ dynamic identity work involving the crossing of artificial borders between identifiable languages, cultures, and genres (Canagarajah, 2013, 2020; Liao, 2018; You, 2011).

L2 creative writing teachers’ theoretical orientations are then critical. According to Disney (2014), creative writing pedagogy as influenced by the world Englishes perspective promotes the hybrid practice of “experimentation, exploration, and indeed creolization” (p. 1). Viewing their learners’ writing in line with identity work or the world Englishes perspective, L2 writing teachers may adopt pedagogical practices and assessment measures that are critically different from teachers who follow strictly a technical approach to L2 writing (Canagarajah, 2015; 2020; Dai, 2010; Hong & White, 2012).

Despite these advances, existing research suffers from the following three limitations. First, existing studies have not closely examined creative writing teachers’ theoretical orientations, especially those of native speaker teachers. The teachers’ experiences and language backgrounds are important. They affect whether the teachers regard their multilingual student writers’ deviational language use as a problem or an expression of creativity and criticality, which in turn can further influence the student writers’ engagement in L2 creative writing. Second, there is little knowledge of what makes an L2 creative writing course successful. L2 creative writing teachers would find reports on previously used approaches, activities, or materials useful in the design of future courses. Third, most of the existing studies have not provided adequate details about how L2 learners’ creative writing was evaluated. Readers might wonder whether L2 creative writing should be assessed the same way as other types of writing, such as timed writing (Lam, 2016), instead of using more plausible ways of evaluation such as writing portfolios (Song & August, 2002). Students’ perception of what their teachers emphasise in their creative writing may also significantly influence how they write, whether creatively or in conformation to prescribed writing conventions.

To address the research gaps concerning L2 English creative writing courses, the following four research questions were formulated for this case study:

- What did the teacher prioritise in the L2 creative writing course?

- How did or didn’t the concept of world Englishes influence the teacher’s teaching and assessment of L2 creative writing?

- To what extent did students’ evaluation of this course correspond to the course objectives stated in the L2 creative writing syllabus?

- Why did the teacher incorporate particular activities into the L2 creative writing course? How did the students perceive these activities?

Methodology

A case study methodology was used to conduct an in-depth investigation of the issues surrounding one specific L2 English creative writing course. What, how, and why research questions directed the research by providing readers a detailed description of the L2 creative writing course; this “detailed, contextualized picture” has been painted with a descriptive case study (Hood, 2009, p. 71). Researchers should clearly define the “boundaries and contexts” of an investigated case so that consumers of the research can appreciate the object studied (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003, p. 71). Thus, we delimited our investigation to one specific L2 creative writing course that included the teacher, the students, and related coursework (e.g., syllabus, assignments, classroom activities). Using a case study methodology allowed us to document one L2 creative writing teacher’s practice and his students’ evaluation of the practice when in the “bounded system” of this L2 creative writing course (Merriam, 1998, p. 9).

Case Selection and Context

Twenty first year and second-year undergraduates majoring in applied foreign languages with a concentration in either translation or business at a public university in southern Taiwan were involved in this case study. Participants enrolled in an elective English creative writing course limited to students majoring in applied foreign languages. Prior to course enrolment, all students had experience and training in writing English for general and academic purposes; however, none had L2 creative writing training or experience. All students had passed the high-intermediate levels of the General English Proficiency Test which is aligned with the B2-B2+ on the CEFR and 6.0-6.5 on the IELTS. All participants agreed to share their opinions regarding the course and to take part in the different research activities. All opinions were gathered after the course grades had been administered to ensure that students did not feel coerced into participating which would have resulted in unreliable data (Master, 2005).

The first author, an English native speaker, was the course instructor and at the time the course was taught had five years of experience in teaching in both ESL and EFL contexts. Here ESL refers to contexts in which the majority of the community speaks English as a native/first language, while EFL refers to contexts in which the majority of the community speaks one or more other languages as their native/first language(s). Students in ESL contexts will have exposure to the language outside the classroom while students in EFL contexts will receive most of their language exposure inside the classroom. This author had taught L2 English general and academic writing courses before this research took place. This was the first time that he had planned and taught an L2 English creative writing course and he received no guidance on constructing or teaching the course.

The use of portfolio writing assessments in the EFL writing classroom integrates learning, teaching, and assessment; this integration can often result in encouraging EFL learner autonomy and motivation that leads to L2 writing performance improvements (Burner, 2014; Hamp-Lyons & Condon, 2000). EFL learners’ engagement in L2 English creative writing promotes their literacy, motivation, confidence, agency, and ability to emote (Banegas, et al., 2020; Hanauer, 2010; Iida, 2011; Zhao & Brown, 2014; inter alia). In addition, L2 creative writing taught by teachers that do not restrict expression only to standard use of English encourages EFL learners to take advantage of their entire linguistic repertoire resulting in identity development (Canagarajah, 2006, 2011, 2013, 2020; Disney, 2014; García & Wei, 2014; inter alia) Thus, we claim a successful L2 English creative writing course includes portfolio assessment and greater emphasis on the content and creativity of student writing instead of conformity to an NS language norm. We argue that creativity can and should be pursued as the main objective in L2 English creative writing courses even when taught by NS teachers. Thus, we found this creative writing course suitable for investigating whether the language ideology, assessment strategies, and language activities resonated with the spirit of the world Englishes and similar pedagogical paradigms mentioned in the literature review. In addition, as the first author was also the teacher of the course, the ease of convenience sampling was also considered when selecting this course as a case for the investigation.

To reduce bias and include both an insider and outsider perspective, the first author invited two other researchers to join the project. The diverse educational backgrounds of the team—Sociolinguistics, L2 Writing, and TESOL—facilitated a holistic approach to the data analysis and discussion of the results. The fact that the course was taught earlier in the first author’s career also allowed for a mature reflection on both what and why particular instructional practices were incorporated into the course. It should still be noted, however, that the creative writing course emphasized creative writing for creative purposes and not linguistic purposes due to the teacher’s own undergraduate educational experiences studying literature and creative writing. The approach used by this teacher’s own past professors in creative writing courses influenced the approaches taken to teach creative writing for creative purposes. The teacher’s approach may have depended on flexibility in how the course was designed and executed; the university in which the course was taught gave no requirements for the course other than it being about creative writing.

Data Collection

Several types of data were collected from students and the teacher, including the creative writing course syllabus, students’ reflection reports, students’ creative writing portfolios, and the teacher’s reflection report. The course syllabus, the students’ reflection reports (n=19, words Mtokens=252, SDtokens=134), creative writing portfolios (n=20), and the teacher’s reflection report (n=1, 3,444 tokens) were collected after the course had been taught. The reflection report was an open-ended written reflection on the course design and implementation.[1] It should be noted that nineteen out of the twenty students voluntarily submitted a reflection report while creative writing portfolios were collected from all students. Pseudonyms were used to ensure the confidentiality of the participants. S1 stands for student 1, S2 for student 2, and so forth. The following prompt was provided to the students to guide writing their reflection reports:

You should detail a) your growth as a creative writer b) course improvements needed c) what you have learned and benefited from this course and d) anything else you wish to express.

Data Analysis

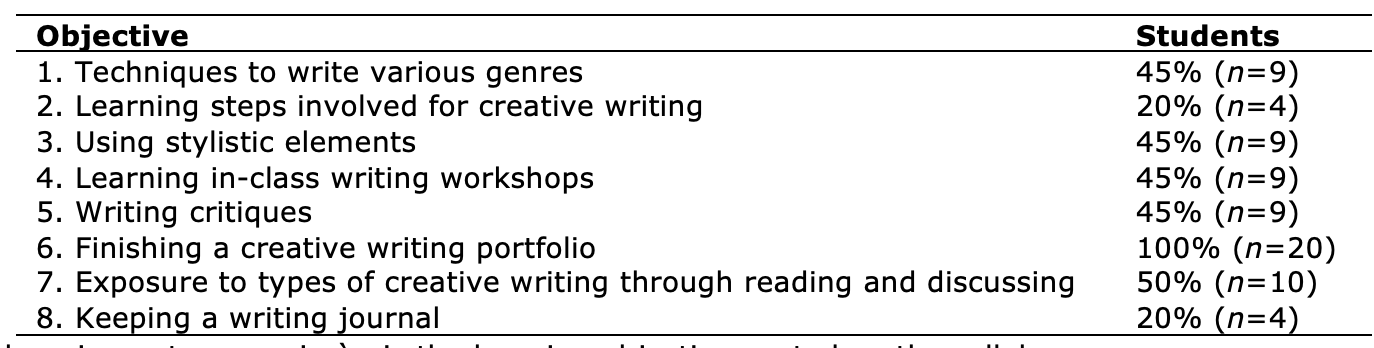

Qualitative content analysis of the students’ reflection reports, the teacher’s reflection report, the creative writing syllabus, and the students’ portfolios were carried out (Schreier, 2012). The analysis began with using the eight learning objectives stated on the course syllabus to establish a thematic framework (see Table 1 for the eight objectives), addressing Research Question 1. To answer Research Question 2, the concepts of world Englishes were drawn upon to consider the global perspective of L2 English creative writing course development and teaching (Canagarajah, 2006). Students’ reflection reports and portfolios were analysed through categorising, labelling, and charting to answer Research Question 3. To answer Research Question 4, a data-driven thematic framework (i.e., Lecturing, Sharing, Workshopping, Journal Writing) was used for the content analysis of the teacher’s reflection report and the syllabus.

Table 1. Students’ learning outcomes vis-à-vis the learning objectives noted on the syllabus

Findings and Discussion

What did the teacher prioritise in the creative writing course?

According to the analysis of the syllabus, the teacher formulated eight learning objectives for him and his students to collaboratively pursue (see Table 1). The course served as an introduction to the creative process in writing articles, biography, drama, essay, fantasy, memoir, poetry, and short story. Its primary purpose was to stimulate students to produce and develop their creative work in a particular genre using specific techniques for each genre. The class centred on the workshop model. This meant that the students had the chance to submit one creative work to the class to be analysed and critiqued by classmates. Additionally, the teacher acted as a guide to help students understand how to better their creative writing by using the guidelines provided in the course textbook. There were no tests or quizzes to assess students’ creative writing or knowledge about writing creatively. Instead, a creative writing portfolio was used to assess students’ creative writing process and progress. The students were also required to visit the teacher’s office once during the semester accompanied by the creative writing journal that they had been keeping throughout the semester for creative writing practice. During this meeting, the teacher and the student would discuss their creative writing processes and progress and the teacher would review the creative writing journal to confirm the students had been keeping the journal. No minimum or maximum number of entries were required for the creative writing journal. Based on the teaching objectives stated in the syllabus, unlike other L2 English creative writing courses that were designed only to support English language learning (e.g., Lim, 2015), this L2 English creative writing course was designed to develop students’ L2 English creative writing skills. The course syllabus indicates that the foci of this course were on teaching and learning L2 creative writing.

The first hour of each class was dedicated to lecturing and discussion of the weekly textbook reading that was sometimes accompanied by in-class creative writing practice and stimulating exercises (e.g., freewriting). The second hour of class often was devoted to discussion of the excerpts from various types of creative writing assigned as reading homework or discussion of students’ workshopped creative writing pieces.

The workshopping involved critiquing classmates’ manuscripts and having one’s manuscripts critiqued in a trusted group atmosphere. The students were involved in two main workshopping activities. They were required to submit at least one of their manuscripts to the class for workshopping and they were also required to write written critiques of all the creative writing pieces submitted to these workshops by their classmates. The creative writing students that shared their writing during these workshops were responsible for making enough copies for everyone in the class the week before workshopping the piece. Then in the week of the workshops, their classmates would share their thoughts on the pieces out loud as a group. No more than four pieces were workshopped within a single week. Most of the workshopping occurred in the last three months of the academic semester after the student creative writers had received training on peer editing and been provided guidance on how to respond appropriately and respectfully to peers’ creative writings during workshops.

After being given examples of written critiques of creative writing pieces and a guideline for writing such critiques (items on critique documents supplied by the teacher were tailored to each genre covered in the course), the students were required to take their peers’ manuscripts home to read and write critiques. When reading these creative pieces, the students were taught to be active readers and offer immediate reactions through parenthetical notes. They were also taught how to use symbols to indicate areas of the text that made them feel good when reading or areas of the text that made them feel work was needed. Students read each workshopped piece at least twice before writing the critiques. The students were also required to complete a say back at the end of the critique document that required a summary of the piece and their reflection on the parts that made them feel good and feel work was needed. After a creative writing piece was workshopped, the students would then give the author and the teacher each a copy of the piece with parenthetical notes attached to the completed critique document.

At the end of the academic term, the students were expected to have produced three pieces of creative writing in at least two genres. They were expected to have rewritten these pieces at least once. They had to include all the drafts of the creative pieces in their portfolio given to the teacher at the end of the term. The portfolio was accompanied by a letter to the teacher introducing the three pieces.

How did or didn’t the concept of world Englishes influence the teacher’s teaching and assessment of L2 creative writing?

As the teacher who designed this course was not an experienced teacher in the field of creative writing, it was valuable to scrutinize whether the skills and teaching knowledge to teach L2 English writing for academic or general purposes could facilitate students’ L2 English creative writing. This included inspection of the materials and assessments employed and what underlying theories were used to support such pedagogical decisions. An investigation of the teacher’s course design and underpinning theories have implications for the applicability of teaching strategies used for general or academic writing in a creative writing context.

Dai (2010) reported that the NS assessor in her study with an awareness of world Englishes could only provide students with suggestions for language use. For instance, “students could note down the expressions that they were not sure of, so that the native English-speaking assessors could suggest more appropriate ones” (pp. 554-555). Dai also noted that working with an NS instructor is helpful for students as it can help them work on “linguistic accuracy” for learning and assessments (p. 556). In the era of world Englishes, the monolingual NS English ideology and accuracy-oriented approach remain one of the teaching or learning targets. In opposition to the role of the NS instructor in Dai’s research, the syllabus developed by the NS teacher in the current study did not have much to do with linguistic accuracy and he did not place himself in a position to make NS-based linguistic suggestions. As exemplified, the main role of the instructor was to give lectures to provide students with fundamental genre-based input. In addition, the syllabus does not prioritise the NS-based accuracy or other NS linguistic requirements in terms of the content of instruction. As the instructor commented in his reflection, “maybe many professors also think how students could write creatively if they can’t even write regular English correctly. In this respect, poetry can be freeing for both students and teachers since poems do not have to follow so-called standardised English.” In other words, no particular linguistic formations or conventions nor accuracy was emphasized in the creative writing course. Some may argue that this is necessary for all creative writing, whether it is in one’s L1 or L2. For example, in the excerpt below from the poem “Centipede,” S14 used unconventional punctuation and capitalization to describe a cut and the treatment she received:

The lightning hit the ground

The land surface cracked and red came out

Like vomiting

One spring after one spring

Then it became a red sea

A needle shuttled in the crack

Like an experienced captain

Leading the ship in the wave

(S15 portfolio)

The prioritization of the teacher’s genre-based feedback was also encouraged through the peer feedback training he provided to the students in the first month of classes; the skills provided through the training was subsequently used by the students when workshopping and critique writing. The students provided peer content feedback that informed their peers about what was enjoyed (i.e., feel good) and what was misunderstood (i.e., work as needed) while reading their creative works. Min (2005) found that peer feedback could be facilitated when learners received training. Through workshopping and other learning activities, feedback training can help peers to clarify intentions, identify problems, explain the nature of problems, and make specific suggestions. There were indications that the students felt that they had received training and acquired skills to write and interact with peers to deliver and receive feedback from the teacher and peers through workshopping. Overall, the teacher and students agreed that the method of peer feedback through workshopping effectively facilitated their L2 English creative writing development. Rollinson (2005) said similar findings were also identified and discussed in the literature on L2 ESL writing. As he concludes,

for the teacher who perhaps wishes to escape from the tyranny of the red pen (if only temporarily) and explore an activity that can complement her own feedback to her students’ writing, collaborative peer group response is a potentially rewarding option. (p. 29)

In this case, the L2 English identity of peers did not affect their ability to deliver feedback.

In many EFL contexts, writing is assessed, not taught (Lam, 2016). In the current study, all the EFL students achieved one learning objective stated on the syllabus: completing a creative writing portfolio. Instead of using the traditional timed examinations to assess students’ writings, the teacher deployed a portfolio-based assessment. The results of this study showed all students were able to compile a creative writing portfolio that showcased their ability to write creatively in at least two different L2 English creative writing genres. As Hamp-Lyons and Condon (2000, p. 61) argue, portfolio-based assessment is suitable to measure students’ L2 creative writing development because this approach offers “a broader measure of what students can do” rather than how accurately students can write in adherence to NS linguistic norms, a practice that “has long been claimed to particularly discriminatory against non-native writers.”

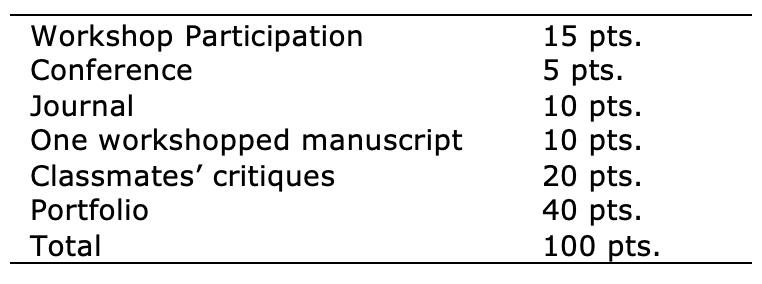

As Table 2 illustrates, none of the assessment activities had direct relevance to NS linguistic requirements. The grading rubric also did not include assessment of students’ writing performance in adherence with NS linguistic norms. The discussion here is not to reinforce the native vs. non-native divide in writing assessment. Instead, the analysis of the assessment rubric highlights how the instructor created a learning environment in which L2 English creative writing was learned and assessed in a wider sociolinguistic and socio-cultural context as previously suggested by Lim (2015).

Table 2. Course grade calculation

To what extent did students’ evaluation of this course correspond to the course objectives stated in the L2 creative writing syllabus?

As shown in Table 1, all students claimed that they completed and submitted their creative writing portfolios. Fifty per cent of the students (n=10) indicated that they were exposed to different types of creative writing through reading the textbook, the examples provided by the teacher, teachers’ works, or peers’ creative works discussed in class during workshopping (see Appendix 1 for an example). Thirdly, 45% of students (n=9) reported that they accomplished the following four learning objectives: using techniques to write various genres, using stylistic elements, learning how to engage in workshopping creative pieces, and writing critiques. Only four students (20%) identified that they learned about the steps involved in creative writing or kept a writing journal. The learning outcomes claimed by the students indicate their achievement of certain L2 creative writing learning goals. The reason no students claimed achievement of all the learning goals could be due to their freedom to discuss any topic they wished in their reflection reports. Thus, students may have prioritized or focused on certain learning objectives they wanted to discuss in the reports. Overall, about 45% of students claimed that they achieved 6 out of the 8 learning objectives on the syllabus.

Taking reading for creative writing skills development as an example, S1 reported “I knew many different kinds of writing from the textbook.” S18 indicated, “I benefited most from reading the masterpieces from our classmates. I’m so impressed by everyone’s ability to construct poems and stories that are so profound and interesting, sometimes even far beyond my imagination.” Students’ responses to reading for writing resonates with Dai’s (2010) argument for reading to enhance creative writing. By this, Dai said, “reading is especially important for students who write in a second language. The selected readings play a dual role in introducing students to more of the wealth of literature, as well as serving as examples of different writing techniques” (p. 550).

S4 emphasised that he not only was exposed to many types of writing but also specified what he learned from the works that he read. He indicated that while enrolled in the course he “read many articles written by the classmates, too. Their stories and poems always let me enjoy so much…for example, in [S15’s] poem, she used many different metaphors to describe the wound.” As Lim (2015) observed when comparing reading the creative writing works of peers or the teacher with those presented in the textbook, the former “is more productive in generating positive writing than finding models in standard literature anthologies and textbooks” (p. 41). The syllabus indicates that the teacher did not use an anthology but instead used a creative writing guidebook along with a set of pre-selected works. S15 emphasised that “what I have learned from this class is the knowledge from the textbook and from your [the teacher’s] sharing. This textbook is not hard to read; after all, it is designed for idiots to learn how to write different genres. However, your [the teacher’s] teaching and sharing of experiences adds some flavour to this class.” S4 and S15 pinpointed how they obtained more benefit from reading their classmates’ and teacher’s works than from reading textbooks.

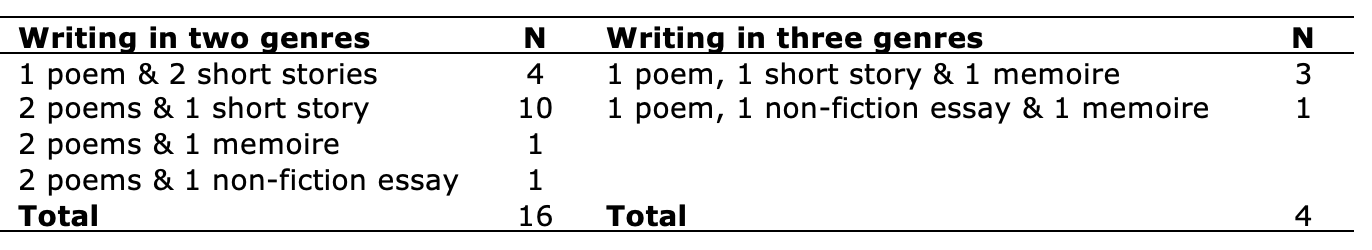

All (n=20) students compiled and submitted creative writing portfolios. The analysis of students’ portfolios indicated that they produced three pieces of creative writing in at least two genres. Table 3 illustrates the twenty students’ creative writing organised by the different genres. Most of the students produced creative writing in two genres and only four out of the twenty students (20%) produced writing in three genres. Twenty students wrote poems, seventeen short stories, four memoirs, and two creative non-fiction essays. The results showed poetry and short stories as the top two genres that students chose to write. The analysis of the students’ portfolios confirms that all students had accomplished at least two learning objectives: learning about the techniques to write in various creative writing genres and finishing a creative writing portfolio.

Table 3. Each student’s writing in different genres

From the analysis of the students’ reflection reports as well as the completed portfolios, all students identified that their learning of L2 creative writing mostly occurred through practising writing, such as finishing the writing portfolio. All the students also agreed that they learned techniques to write in at least two different creative writing genres. Half of the students agreed that they had learned creative writing by using creative writing techniques to write creatively in various genres, by using stylistic elements, and through participation in in-class workshopping, and via the evaluation of peers’ writing through the writing of critiques.

The low percentage of students who claimed they had learned steps in writing creatively and how to keep a journal revealed a tendency towards students’ feeling it difficult to achieve these two learning objectives. For instance, to learn about the steps involved in producing creative writing, S4 indicated that “…during writing a story, it was so difficult to make my story be logical. I had to be careful about every detail. I had to control every small part of the story. If not, the story would confuse my audience or the story would become very contradictory.” Another example of this was S8’s comment on how writing a short story was not easy. S8 said, “to me, short story was the real challenge, I revised it again, again, but I saw no breakthrough. I think it would definitely need to be revised more and more…” Holding a positive-negative mixed view about keeping a journal, S8, for instance, indicated that “writing critiques and a journal were time-consuming, and as lazy as I am, it was really a challenge. Even so, I found that I did really enjoy the moment when I put what was inside my head in paragraphs word by word.” Another example is S13’s comment on keeping a writing journal, indicating that “And in my opinion, the journal which you [the teacher] have asked us to write also has benefited us. It’s really tiring to write [in a] journal owing to laziness, but it’s really useful. It can not only record my life but also improve my writing.” The results show that achieving the learning objectives was not simply about whether the learning objectives have been accomplished but also about what challenges or how difficulties students faced in order to fulfil the goals. Achieving the learning targets was not about a product but a process of facing and solving the difficulties.

Why did the teacher incorporate particular instructional activities into the L2 creative writing course? How did the students perceive these activities?

The discussion below is divided into four subsections to compare the teacher’s instructional activities and the students’ evaluations of these activities.

Lecturing

According to the teacher’s reflection report, he emphasised that this course was not lecture-based but he did note that “these students were used to lecturing.” Thus, the teacher decided to lecture “for one class period (about 1 hour) on the textbook” each week when he met the students for the two-hour lesson. According to the syllabus, the content of instructional activities should have been “the discussion of the weekly textbook reading, which will often include in class writing exercises and sharing of the writing.” By this, the teacher added that giving lectures aimed to help students “build up their background knowledge of the different genres” because the teacher assumed that “students would not know all of them, especially creative non-fiction or memoir.” Despite the fact that the teacher’s lectures were not the focus of this course, five out of eighteen students (27.8%) reported that the teacher’s lectures benefited their creative writing skills development. For instance, S12 reported, “from the textbook and from the lecture in class, I know the skills of writing. [F]or example: when writing a story, we only write the names of the protagonist and other important roles[;] we don’t need to think of names of those who just appear once or so.” S10 also indicated that “sometimes a method [is] maybe too abstract and equivocal, but [the] teacher can describe it clearly. I think this class not only helps me improve the ability of talking [about creative writing] but also my creative writing.” S1 pointed out, “I knew many different kind[s] of writing from the textbook.” S14 also pointed out how useful the teacher’s lectures were by stressing that “the best part of my improvement and growth is the way of my writing through listening to the teacher’s lectures.” Overall, although lecture-based teaching was not a claimed main focus of this course by the teacher, still, about one-fourth of the students emphasised that they learned creative writing skills from the teacher’s lectures.

Sharing

For the second activity, sharing creative writing, the teacher selected “some of his own creative writing to share with the class.” Five out of eighteen students, 27.8%, responded to a similar feature of the course in their reflection reports, indicating how they benefited from sharing their creative writing and reading their peers’ or teacher’s creative writing. As S9 reported, “what impress[ed] me most were the pieces sharing. I can read other people’s writing and make comments for them. On one hand, I can refresh my vocabulary by reading their writing. On the other hand, we can encourage each other to do a better job during the commentary.” Holding a similar view on sharing, S11 emphasised, “In class, everyone just feels free and have no stress to share their feelings with all the people in the class[;] through sharing, I also can find different viewpoints that really inspire me.” S11’s comment echoed the teacher’s claim about his efforts to “create a safe, secure place for the learners to share their writings.” Peer learning has been identified by other researchers as effectively facilitating students’ creative writing knowledge and skills (Dai, 2010; Lim, 2015). Many students claimed to have benefited from the safe space that the teacher created for sharing and receiving peer feedback.

Workshopping

One focus of the course design was on workshopping. The teacher emphasised that he aimed to develop students’ “critical reading skills” and help students develop the abilities to “not only receive feedback but also provide feedback about peers’ creative works.” To participate in workshopping, the teacher indicated that students needed to be “active readers” by bringing peers’ work home, reading them at least twice, noting the “areas of the text that they feel are good as well as those they feel need work” and completing the “critique handout” (see Appendix 1). According to the teacher, the critique handout served as a guide for students to write critiques on peers’ work. Students brought the completed critiques to class to discuss each other’s creative pieces during the workshops. In class, the teacher asked students to listen to other students’ interpretations of their work and then try to incorporate the feedback into subsequent revisions. According to the teacher’s observation, he found that students enjoyed this activity because “they needed to slow down, think about what is written on the page and never to assume.” The teacher concluded, “I think a lot of the learning that went on during the classes was during the workshopping.” As can be seen, the teacher highly valued the contribution of the workshopping activity to how students learned to produce written and spoken critiques. He also attributed the growth in their abilities to write creatively to the experiences gained through the workshopping activity.

Nine students (45%) indicated that they learned how to read critically and how to share opinions on creative writing produced by their peers through the process of reading, discussing, and giving/receiving feedback during workshopping. Table 3 provides a representative sampling of nine students’ comments on how they learned creative writing through the reading and discussing of their peers’ creative works.

|

S1: I have a lot of fun when classmates sit in a circle, share their own opinions and discuss what exactly it means. S3: Most of all, I can have opportunities to share my opinions about one’s work during class. S10: I think that I learn a lot from classmates’ poems and stories, because I can read so many [and] get something from their creations, and they provide me a chance to get more information. S12: ….and simultaneously I have learned how to use say-back to give suggestion to others. S13: I also want to mention about the sharing from the classmates. I really like to read the writings from them because I think it’s interesting to read the works from my friend[s]. S15: I can appreciate the classmates’ writing. S16: I really like this course. I think it’s interesting because I can read many other classmates’ works. S17: I benefited most from reading the masterpieces from our classmates. I’m so impressed by everyone’s ability to construct poems and stories that are so profound and interesting, sometimes even far beyond my imagination. S18: I thought in this class, it was interested to see others’ different point[s] of view upon the same work. When I received critic[i]s[m] from our classmates, I thought it was amazing that there were so many questions. |

Table 3. Students’ perceptions of workshopping

Most students confirmed that workshopping facilitated their L2 creative writing skills. A similar finding was also identified in Dai’s (2010) research into the positive impact of running workshops on students’ creative writing development. The students learned how to explore the meanings of creative writing pieces (i.e., S1), share opinions (i.e., S3; S13), give peers suggestions/feedback (i.e., S12), learn from peers (i.e., S10; S17), appreciate peers’ creative writing (i.e., S17), and explore different views on the same work (i.e., S18). The results pointed out that students learned several facets of creative writing through attending workshops and participating in the workshopping process. This resonated with the teacher’s observation of the contribution of workshopping to students’ creative writing outcomes. The results also indicated the diverse nature of learning how to write creatively in one’s L2. However, the creative writing learning outcomes that occurred through reading and discussion-centred activities varied among students despite their attending the same course and participating in the same activities.

Journal Writing

The teacher asked students to “keep a creative writing idea journal,” aiming to assist students in writing “freely and with confidence.” The teacher indicated, “students enjoyed the journaling a great deal. Many of them explained that it gave them a good outlet to write even though it was hard for them to get in the habit of keeping a journal in English.” As Tuan (2010) argues, journal writing motivates students to keep writing and benefits students’ L2 writing skills development. However, the teacher’s claims about what students had conveyed to him about keeping a writing journal did not correspond precisely to what the students felt about keeping a creative writing journal. It seemed that the teacher held positive attitudes towards keeping a writing journal as a learning target, which was different from students’ mixed feelings about keeping a creative writing journal. The students that did reflect on journal writing mostly reflected on how difficult it was to keep a creative writing journal although without going into detail about what made keeping the journal difficult.

Conclusion

The findings of this study are based on empirical data collected after a teacher planned and implemented an L2 English creative writing course. The goal of the study was to analyse the components, assessment strategies, learning activities, and teacher ideology of this successful L2 creative writing course. While the teacher prioritised eight learning objectives, none of them suggested an ideology or orientation towards encouraging students to produce L2 English creative writing that mimicked that of NS writers; furthermore, none of the assessment activities had any noticeable relevance to NS norms. Lecturing, sharing, and workshopping were all found to be effective learning and assessment activities, while students experienced the most difficulty with keeping a creative writing journal. The students reported that portfolio assessment, exposure to different creative writing genres, learning about various genre techniques through lecturing, using stylistic elements in creative writing, engaging in workshopping creative pieces, and writing critiques on peers’ creative writing were activities that helped them learn how to write creatively in English.

As students had the freedom to write in their reflection reports on any course evaluation topics that pleased them, we cannot deny the possibility that there were students that fulfilled other learning objectives stated in the syllabus but did not comment on them in their reflections. The methodological implication for future research is the use of a questionnaire in combination with reflection reports to effectively obtain direct quantitative evidence on whether students’ learning outcomes correspond to the stated teaching objectives in the syllabus. While the teacher reported that many of the students’ writing was “thought provoking and engaging,” it was beyond the scope of the current study to measure through detailed discourse analysis the creativity or the contents of the works produced by the students.

This study provides some insights on how to teach an L2 English creative writing course successfully. One strategy is to limit form-focused instruction and feedback by adopting a genre-based and process-oriented teaching approach. Portfolio evaluation should also be encouraged. Teachers should also be deliberate in using various pedagogical activities such as lecturing, workshopping, and guided peer feedback giving to scaffold their students’ creative writing development.

The teacher in this study pondered over the linguistic variation of English and its relationship to L2 poetic expressions. He did not use norms of standardised English to assess his students’ writing performance. L2 English writing teaching and assessment approaches combined with a world Englishes view served as a complementary set of skills to help the teacher plan and implement a new L2 English creative writing course successfully. In this sense, an L2 creative writing course can be an ideal site to challenge monolingual ideology from the ground up.

References

Arshavskaya, E. (2015). Creative writing assignments in a second language course: A way to engage less motivated students. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 10, 68-78. https://doi.org/10.46504/10201506ar

Babaee, R. (2015). Interview with Alan Maley on teaching and learning creative writing. International Journal of Comparative Literature & Translation Studies, 3(3), 77-81. https://www.journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/IJCLTS/article/view/1848/1701

Banegas, D. L., Roberts, G., Colucci, R., Sarsa, B. (2020). Authenticity and motivation: A writing for publication experience. ELT Journal, 74(1), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz056

Burner, T. (2014). The potential formative benefits of portfolio assessment in second and foreign language writing contexts: A review of the literature. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.03.002

Canagarajah, A. S. (2006). The place of world Englishes in composition: Pluralization continued. College Composition and Communication, 57(4), 586-619. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20456910

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1

Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2015). “Blessed in my own way”: Pedagogical affordances for dialogical voice construction in multilingual student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 27, 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2014.09.001

Canagarajah, A. S. (2020). Transnational literacy autobiographies as translingual writing. Routledge.

Cummins, J., & Early, M. (2011). Introduction. In J. Cummins & M. Early (Eds.). Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools (pp. 3-19). Institute of Education Press.

Dai, F. (2010). English-language creative writing in mainland China. World Englishes, 29(4), 546-556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2010.01681.x

Darvin, R. (2019). Creativity and criticality: Reimagining narratives through translanguaging and transmediation. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(4), 581-606. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0119

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2015). Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 36-56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000191

Disney, D. (2014). Introduction: Beyond Babel? Exploring second language creative writing. In D. Disney (Ed.). Exploring second language creative writing: Beyond Babel (pp. 1-10). John Benjamins.

Earnshaw, S. (Ed.) (2007). The handbook of creative writing (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

Edelsky, C. (2003). Theory, politics, hopes, and action. The Quarterly, 25(3), 10-19. https://archive.nwp.org/cs/public/download/nwp_file/520/Theory.pdf?x-r=pcfile_d

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education Palgrave Macmillan.

Hamp-Lyons, L., & Condon, W. (2000). Assessing writing portfolios: Principles for practice, theory, and research. Hampton.

Hanauer, D. I. (2010). Poetry as research: Exploring second language poetry writing. John Benjamins.

Hanauer, D. I. (2012). Meaningful literacy: Writing poetry in the language classroom. Language Teaching, 45(1), 105-115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444810000522

Hassall, P. J. (2006). Developing an international corpus of creative English. World Englishes, 25(1), 131-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0083-2919.2006.00451.x

Hassall, P. J. (2011). The extremely short story competition: Fostering creativity and excellence in formal and informal learning contexts in the UAE and internationally. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Gulf Perspectives, 8(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.18538/lthe.v8.n2.64

Hong, Y., & White, J. (2012). Writing without fear: Creativity and critical pedagogy in Chinese EFL writing programs. Journal of Asian Critical Education, 1(1), 8-20.

Hood, M. (2009). Case study. In J. Heigham & R. Croker (Eds.) Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction.Palgrave Macmillan.

Hyland, K. (2016). Teaching and researching writing (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Iida, A. (2010). Developing voice by composing haiku: A social-expressivist framework for teaching haiku writing in EFL contexts. English Teaching Forum, 48(1), 28-34. https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/10-48-1-e.pdf

Iida, A. (2011). Revisiting haiku: The contribution of composing haiku to L2 academic literacy development [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Iida, A. (2012). The value of poetry writing: Cross-genre literacy development in a second language. Scientific Study of Literature, 2(1), 60-82. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.2.1.04iid

Iida, A. (2016). Poetic identity in second language writing: Exploring an EFL learner’s study abroad experience. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(1),1–14. https://ejal.info/index.php/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/10.32601-ejal.460985-537353.pdf

Iida, A. (2017). Expressing voice in a foreign language: Multiwriting haiku pedagogy in the EFL context. TEFLIN Journal, 28(2), 260-276. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v28i2/260-276

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. John Benjamins.

Kim, K. M. (2018). A humanized view of second language learning through creative writing. Journal of Creative Writing Studies, 3(1), 1-24. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol3/iss1/7

Kim, K. M., & Park, G. (2020). “It is more expressive for me”: A translingual approach to meaningful literacy instruction through Sijo poetry. TESOL Quarterly, 54(2). 281-309. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.545

Kramsch, C. (2009). The multilingual subject. Oxford University Press.

Lam, R. (2016). Assessment as learning: examining a cycle of teaching, learning, and assessment of writing in the portfolio-based classroom. Studies in Higher Education, 41(11), 1900-1917. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.999317

Li, H. (2015). xiě chū xīn líng shēn chǔ de gù shì - fēi xū gòu chuàng zuò zhǐ nán (yīng hàn shuāng yǔ bǎn) [Writing stories from our hearts: A guide to non-fiction writing (English-Chinese bilingual version)]. Tsinghua University Press.

Li, X. (2007). Souls in exile: Identities of bilingual writers. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 6(4), 259-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348450701542256

Liao, F.-Y. (2018). Translingual creative writing pedagogy workshops: University teachers’ transformations on pedagogical ideas(Publication No. 10785698) [Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/openview/d20c3c5a1a405b816ef0638edcf39d59/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Lim, S. G.-L. (2015). Creative writing pedagogy for world Englishes students. World Englishes, 34(3), 336-354. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12148

Maguire, M. H., & Graves, B. (2001). Speaking personalities in primary school children’s L2 writing. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4), 561-593. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588428

Master, P. (2005). Research in English for specific purposes. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 99-115). Erlbaum.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Case study research in education. Jossey-Bass.

Min, H.-T. (2005). Training students to become successful peer reviewers. System, 33(2), 293-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.11.003

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Pearson Education.

Pfeiffer, V. F., & Sivasubramaniam, S. (2016). Exploration of self-expression to improve L2 writing skills. Per Linguam, 32(2), 95-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.5785/32-2-654

Rollinson, P. (2005). Using peer feedback in the ESL writing class. ELT Journal, 59(1), 23-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci003

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

Skinner, E. N., & Hagood, M. C. (2008). Developing literate identities with English language learners through digital storytelling. Reading Matrix, 8(2), 12-38. http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/skinner_hagood/article.pdf

Song, B. & August, B. (2002). Using portfolios to assess the writing of ESL students: A powerful alternative? Journal of Second Language Writing, 11(1), 49-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(02)00053-X

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

Tuan, L. T. (2010). Enhancing EFL Learners’ writing skill via journal writing. English Language Teaching, 3(3), 81-88. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v3n3p81

Yang, S. (2013). Autobiographical writing and identity in EFL education. Routledge.

Yang, S. (2018). Potential phases of multilingual writers’ identity work. In X. You (Ed.), Transnational writing education: Theory, History, and practice (pp. 115-137). Routledge.

Yang, S. (2020). Meaningful literacy and agentive writer identity. MEXTESOL Journal, 44(4). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=21871

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

You, X. (2011). Chinese white-collar workers and multilingual creativity in the diaspora. World Englishes, 30(3), 409-427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2011.01698.x

You, X. Y. (2016). Cosmopolitan English and transliteracy. Southern Illinois University.

Zhao, Y. (2011). L2 creative writers: Identities and writing processes [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], University of Warwick. http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/45919

Zhao, Y. (2015). Second language creative writers: Identities and writing processes. Multilingual Matters.

Zhao, Y., & Brown, P. (2014). Building agentive identity through second language (L2) creative writing: A sociocultural perspective on L2 writers’ cognitive processes in creative composition. The Asian EFL Journal, 16(3), 116-154. https://www.elejournals.com/asian-efl-journal/the-asian-efl-journal-quarterly-volume-16-issue-3

[1] Although only the teacher reflection report was analyzed, several synchronous chat sessions between the third author and the creative writing teacher were arranged to clarify particular statements made in the reflection report.