The need to use the English language for personal, academic, and professional purposes is growing around the world. Mexico is one of many countries implementing programs to increase the level of English among its students in elementary, secondary, and tertiary education. It was the first country in Latin America to make English language study obligatory from kindergarten to 12th grade in public schools throughout the country (Sayer, 2015). The National Program for English in Basic Education was rolled out in 2009, and expanded in 2012. In 2017, the original program was scrapped, but another, similar program—the National Program of English (PRONI)—was implemented in its place.

In spite of these efforts, the country still lags in English proficiency. According to Education First (2020), an organization that carries out yearly analyses of the levels of English in 100 countries and regions around the world, in 2019, Mexico obtained a low score, and placed 67 out of the 100 countries. In Latin America, it ranked 16th out of the 19 countries evaluated (Education First, 2020). Therefore, it is important to identify factors that contribute to proficiency among English language learners and use these to improve learning outcomes.

This article describes a study designed to understand the variables which have the greatest impact on English language proficiency in upper secondary school students. The study builds on previous research into the topic, which was carried out at one private university in a large urban center in western Mexico (Santana, García-Santillán, Ferrer-Nieto, et al., 2017). The present study is intended to broaden this research by including a larger number of participants in both private and public universities in different cities across Mexico. By shedding light on the factors that lead to greater proficiency, the study enables us to make recommendations to improve language teaching at the secondary school level.

Literature Review

Learning a second language successfully depends on a variety of factors; some of these are individual, while others are social. Among the individual factors, are the learner’s personality, aptitude, motivation- both the type and the strength of motivation, learning strategies, anxiety and self-esteem, willingness to communicate, and beliefs (Dörnyei, 2014; Mitchell & Myles, 2004) as well as the practical need for the language, and a sense of belonging to a community of target language speakers (Santana, García-Santillán, Ferrer-Nieto, et al., 2017).

Numerous studies (for example, Dabarera, et al., 2014; Huang & Nisbet, 2019; Robillos, 2019; Santana, 2005) show that learners’ use of strategies—especially metacognitive strategies—is associated with greater proficiency. Reilly and Sánchez-Rosas (2019) looked at the role of both positive and negative emotions in language learning. They found that low achieving students tend to experience more negative emotions, whereas high achievers report higher levels of enjoyment and other positive emotions. Bonilla-Jojoa and Díaz-Villa (2019) studied socio-affective factors in English language learning. They found that these play an important role in successful or unsuccessful learning. They also found that individual traits are important, but that the teacher’s role is crucial in determining student attitudes toward that language class.

Anxiety is another individual trait which has been studied extensively (see Von der Embse et al., 2018 for a meta-analysis). The authors’ own work into test anxiety (Santana & Eccius-Wellman, 2018; Santana & Ventura-Michel, in press) has found that test anxiety is associated to concepts of self-worth, and has a negative impact on language proficiency test scores, especially among women.

Saville-Troike and Barto (2016) also mention the importance of social, economic, and political variables, learner experiences, identity, and attitudes. Positive attitudes, especially towards oneself, one’s own language, and towards speakers of the target language, have been found to increase proficiency in the second language (Brown, 2000; Santana, García-Santillán, Ferrer-Nieto, et al., 2017).

Social factors include pedagogical aspects, such as methodology, learning context, and teacher expertise (Guzmán, 2017), or other external factors, such as socio-economic status and social context. These last two lead to an increase or a decrease in learning opportunities (Gholami, et al., 2012) such as interaction with native speakers, access to better education, and greater expectations and support from learners’ parents. López-Montero et al., (2014), working in Costa Rica, found that students from lower socio-economic levels did suffer from a lack of opportunities and access to better schools, but they also found that these students frequently had greater motivation to study, allowing them to overcome obstacles.

A previous study by the authors (Santana, García-Santillán & Escalera-Chávez, 2017) looked into cognitive, affective and social factors that lead to proficiency. The study found that the greatest predictors of proficiency among our participants were type of high school they attended (private vs. public), number of instruction hours, having studied at a language school, having studied with a private teacher, having lived abroad, and time spent reading in English. Additionally, the study found that motivation to learn and perceived usefulness of the language were less important among our population.

This present study delves into why studying at a private school may lead to better language proficiency among incoming students at Mexican universities. The research questions are:

1) Which factors have a significant influence on English language proficiency in students entering university? and 2) To what degree can these influential factors close the proficiency gap between public and private school students?

The following sections explore some differences between private and public schools in Mexico. Understanding the differences between public and private education in Mexico can help explain why the country as a whole does not achieve greater language proficiency. This exploration may identify, at the same time, areas of opportunity to help address the problem, not only in Mexico, but also in other regions with similar conditions.

Public versus Private Education

In Mexico, as in much of Latin America, English language teaching and learning in public education lags behind its counterpart in private schools. As Davies (2011) explains “...generally, results in English language learning in public education are still poor, except in certain cases such as public university language centres” (p. 5). An oft-cited study by González Robles et al. (2004) found that over 95% of public school students in Mexico failed a test of English competence upon entering the university. Similar results in other Latin American countries are reported by de Almeida (2016), Mora et al., (2013), Porto (2016), and Ramírez-Romero and Sayer (2016), among others.

This fact has been variously explained by different factors, including class size, lack of resources, lack of teacher expertise, number of instruction hours offered, and inappropriate teaching methodologies (de Almeida, 2016; Basurto & Gregory, 2016; Davies, 2011; Varona Archer, 2012). Some of these factors will be explored in the next sub-sections.

Lack of Resources

A study carried out by Dietrich (2007) in northern Mexico mentions that in some public schools, cold and rain enter the classrooms. Urban schools tend to be better outfitted than those in rural areas are, but even so, many public schools must make do with minimal resources. Pamplón and Ramírez-Romero (2013) and Sayer (2018), for example, observed teachers working without textbooks. They explained that the textbooks sometimes arrived after half the school year had passed. The teachers wrote sentences on the board or dictated, while students copied into their notebooks, wasting valuable class time. Teachers used their own funds to make photocopies of discrete exercises from books, but these did not necessarily fit into the sequence of the class.

Private schools in Mexico are usually better equipped, with computers for additional language practice, a dedicated website or platform for extra learning activities, and libraries (Dietrich, 2007; Sayer, 2018). As López-Montero, et al. (2014) point out, access to cultural capital in the form of books, computers, and internet access, “may have a profound influence upon whether, what and how any individual learns a language” (p. 439).

Number of Instruction Hours

In many Latin American countries, few class hours are devoted to the study of English. In Mexico, three forty-five-minute sessions weekly represents a dramatic increase in instruction hours compared to previous efforts (Sayer, 2015). In contrast, to earn the right to call itself “bilingual”, a private school must offer at least 10 hours weekly of second language instruction. By the time a child in the public system has finished middle school, he will have had 1060 hours of English; a student in a private bilingual school will have had almost 3000 hours of English in the same period. Research by Serrano and Muñoz (2007) suggests that more hours of language instruction per week are beneficial to learning. Likewise, more hours of input have been found to lead to greater proficiency (Muñoz, 2015).

Teaching Methodologies

Bremner (2015) highlights the fact that most English classes offered in public schools in Mexico are still very much teacher-centered. This is not surprising considering class size and lack of even basic teaching materials, such as textbooks.

In spite of these conditions, the expectation is that teachers will use some kind of communicative approach in their classes, and that students will be able to practice their speaking skills (Bremner, 2015). De Almeida (2016) questions if communicative methods are appropriate in this context, considering that these tend to work better in smaller, more homogenous groups with more motivated learners, such as those found at language institutes. In public schools, the norm is for the intact class to study English together, regardless of previous knowledge or skills, leading to mixed-ability groups in terms of language knowledge. Thus, struggling students, true beginners, and more advanced learners are all studying the same material, with varying degrees of success.

Finally, Davies (2009) mentions that there is no dedicated program for English in upper secondary in Mexico. These courses tend to repeat what students have been studying since primary school, following the first and second books of the series of any international course program, regardless of students’ previous knowledge.

Reading in a Second Language

Numerous studies have shown that reading can help learners improve their general language proficiency; that is, reading not only influences reading ability, but other language skills, as well (Bamford & Day, 2004; Grabe, 2009; Renandya & Jacobs, 2016, among others). This is because reading exposes learners to important amounts of input, including vocabulary. In turn, greater vocabulary knowledge has an impact on listening, speaking, and writing skills (Renandya & Jacobs, 2016).

Robb and Kano (2013) advocate for additive extensive reading (ER); that is, extensive reading done outside the classroom, rather than in class. As they mention, “[t]eachers who are already saddled with more material to cover than feasible in limited classroom hours are reluctant to sacrifice time for ER in their classes” (p.235). In a large-scale study carried out at a Japanese university, the authors found that extensive reading was effective in improving students’ reading skills, as measured by pre- and post-test scores.

Nakanishi (2015) carried out a meta-analysis of 34 studies on extensive reading research and found significant gains among students who followed an ER program. Ruiz de Guerrero and Arias Rodríguez (2009) in Colombia, and Varona Archer (2012) in Mexico, are some of the few extensive reading studies carried out into extensive reading in the Latin American context. The former found gains in several areas of participants’ language proficiency. The latter offers diverse strategies for implementing an ER program in the Mexican context.

The Present Study

As can be seen, there are many possible reasons to explain the gap between English language learning in private and public schools in Mexico. These reasons include lack of resources, fewer instructions hours, and inappropriate teaching methodologies.

The objective of this study was to understand the factors that lead to English language proficiency among students entering Mexican universities. As mentioned above, the research questions were:

Which factors have a significant influence on English language proficiency in students entering university?

To what degree can these influential factors close the proficiency gap between public and private school students?

Methodology

Participants

The study was carried out among students from four universities in four different regions of Mexico. In order to obtain a representative sample, six universities had been selected for the study (located in the northern, western, central, eastern, and southern regions of the country) because the researchers had contacts there who could administer the questionnaire and placement test. Ultimately, two of the universities were unable to participate for administrative reasons. These were located in the north, and in Mexico City. Of the four participant universities, three were private and one was public. In total, there were 1,188 participants of which 963 were from private high schools and 225 public high schools. Of the total 558 were male and 630 were female.

Instruments

These included a questionnaire, and an online placement test, as described below.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed specifically for the purpose of this study and included seven questions plus two identification questions. The questions were adapted from the background survey questions included in the English Language Assessment System for Hispanics II (ELASH II) test. On the ELASH, the questions are intended for statistical purposes and gather information about test-takers’ language learning background and experience, their motivations to study the language, and their perceived strengths and weaknesses in English (College Board, 2019). The questionnaire does not include questions related to individual differences although these are very important to language learning (Dörnyei, 2014).

In other studies, the researchers have focused on some of these individual differences, such as attitudes towards learning the language (Santana, García-Santillán, Ferrer-Nieto, et al. 2017), anxiety (Santana & Eccius-Wellmann, 2018), or metacognition (Santana, 2005). The focus of the present study was background factors which lead to greater proficiency in the English language, as measured by a placement test.

The questionnaire asked the following questions. The first two were general questions. The X designations facilitate understanding of the tables and graphs. (Also see Appendix):

i. Are you male or female?

ii. What is your university?

X1. How long have you studied English?

X2. Did you study in a public or private high school?

X3. Was your school bilingual?

X4. Have you studied English in a language institute?

X5. Have you studied English with a private teacher?

X6. Have you ever lived in an English speaking country? How long?

X7. How often do you read books, magazines, or newspapers in English?

Question X2 serves to divide the participants into two distinct groups. Questions X4 to X6 tell us if the students had access to language instruction outside of their curricular classes. The complete questionnaire is included in the Appendix.

Prior to this study, The questionnaire was piloted with 218 students at a single institution (one of the same institutions in this current study). The pilot showed that the factors that significantly influence proficiency were hours of instruction, type of institution (i.e., private vs public), study abroad, and frequency of reading (Santana, García-Santillán & Escalera-Chávez, 2017). Questions related to motivation to study, perceived usefulness of the language, and perceived ability for language learning were eliminated because they did not show a significant effect on proficiency.

In the current study, the questionnaire was delivered via Google Forms between late July and late September 2017. A coordinator at each university was responsible for taking participants to the computer center at their respective institution. Students were informed of the purpose of the study and were told that if they were not willing to participate, they could leave without any consequences. The students who remained were shown a slide with instructions for the placement test, and a link to the questionnaire. Individually, they followed the link, and responded to the questionnaire. Upon closing the questionnaire, the link to the placement test appeared. Participants followed the link, and completed the test. The student identification numbers were collected on the questionnaire, and both names and identification numbers were collected on the test. This was done to be able to match the data from both instruments. However, any identifying information was removed from the database before analyzing the results.

WebCAPE Placement Test

The Computer Adaptive Placement Exam (CAPE) was developed at Brigham Young University in the 1990s. Since 2002, it is only available online, thus, it was re-named webCAPE. There are versions for various languages, but the version used for this study was the grammar test of the English as a second language (ESL) version. The test has a databank of up to 1000 questions. Test-takers are given six initial questions to establish a base level; depending on how these questions are answered, the test displays the following questions at one level above or below, to “fine tune” the level. The fine-tuning reduces the chance for lucky guesses, or errors through distraction. Once the test taker has answered four questions from the same level incorrectly, or five questions at the highest level correctly, the exam closes and displays the level obtained. For the ESL version, levels are calibrated to the American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) proficiency guidelines, and each testing center matches these to their own program levels (WebCAPE. https://perpetualworks.com/webcape/overview)

For the purposes of this study, the scores were matched to the levels of the Common European Framework.

It is also important to mention that only the grammar portion of the webCAPE was used in this study, due to time constraints. Thus, what was measured was knowledge and usage of English grammar, not speaking ability.

Procedure

To compare English proficiency among students coming from private or public high schools, the first step was a Student’s t-test for mean test scores, to know if their means were statistically different.

The null hypothesis states that both means are equal, and the alternative hypothesis is that the two test scores means are statistically different with a significance of 0.05.

.png)

If the means are different, a multiple linear regression has to be run, including the variables X1, X3, X4, X5, X6, and X7. X2 is the variable which identifies a student coming from a public or private high school.

The multiple linear regression line was run for each type of high school. The multiple regression line offers information of which variables have a significant influence on test-scores (TS). This begins to answer our first research question: which factors have a significant influence on English proficiency of students entering the university, for each type of school?

The null hypothesis states that all coefficients of the regression line are zero, while the alternative hypothesis is that at least one coefficient of the line is not equal zero, with a significance of 0.05.

.png)

Of all significant variables in the regression line, which are the ones that contributes more to the test score? That is, which ones have the greatest coefficient?

The independent variables of the greatest coefficient and the dependent variable Test Scores per type of high school are graphed to better illustrate the results. A simple regression line was run with test scores as dependent variable and the variable that contributes more to these test scores. The purpose of this regression line is to know how much this variable contributes to test scores if it is taken as a single independent variable. Knowing this can help determine how to close the proficiency gap between public and private school students. This will help answer our second research question: To what degree can these factors close the proficiency gap between students from public and private high schools?

Results and discussion

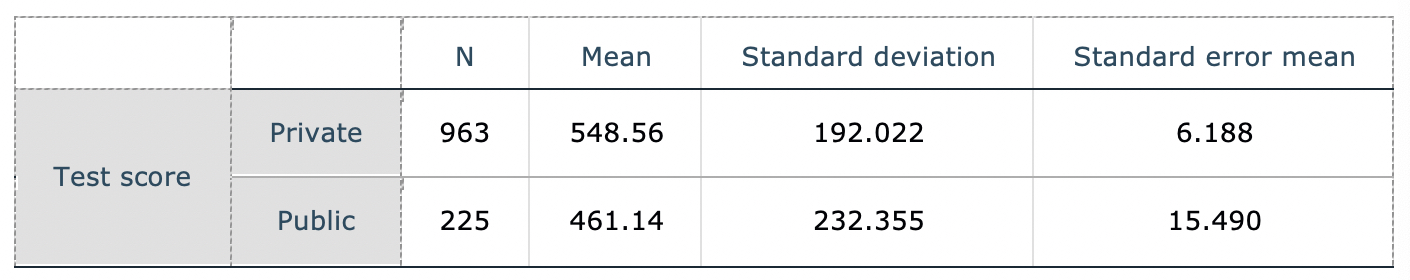

Students coming from a private school scored higher on the placement test than those coming from a public school; the means are 548.56 vs. 461.14 as seen in Table 1. In terms of the Common European Framework of Reference, these are equivalent to levels B2 vs. B1.

Table 1. Group statistics

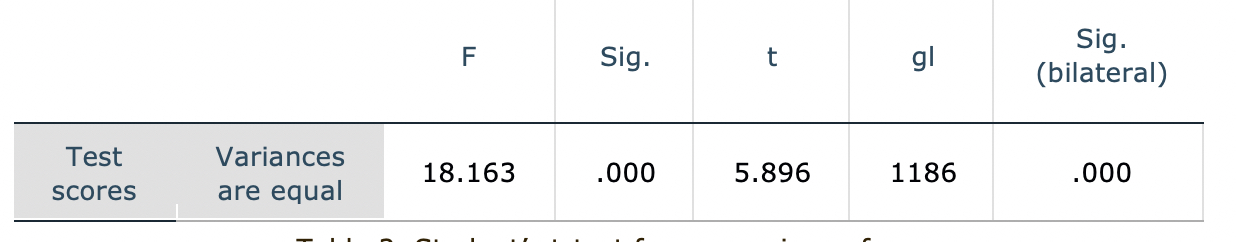

A comparison of means (Student’s t-test) was run to establish if the means of test scores of students coming from different types of high school were statistically different. The test found that the means were statistically different, with a p-value of 0.000 as seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Student’s t-test for comparison of means

Because the means were significantly different, it made sense to examine which of the variables might have influenced test scores per type of high school.

Students from Public High Schools

Table 3 shows the independent variables of the multiple regression line that confirms the dependence of test scores (TS) for the students coming from a public high school. These are the factors which have a significant influence on language proficiency among these students.

Table 3. Multiple regression line for public school students

Thus, for students from public high schools, scores on the placement exam depended on: how long they have studied English (X1), if they studied at a language institute (X4), if they lived in an English-speaking country (X6), and how often they read in English (X7). However, variable X7, the frequency of reading in English, is the variable with the greatest coefficient. This is the regression line.

Because the previous regression line shows that the coefficient for X7 is greater than that of the other variables, we then considered only variable X7 as the independent variable and the test score as the dependent variable, To determine if slope and interception are statistically significant, a simple regression line was run on IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 23). Table 4 shows this regression line.

Table 4. Regression line of test scores vs. frequency of reading

The simple regression line is:

That is, 255 points on the placement test is equivalent to an A2 level on the CEFR, whereas 447 is equal to a high B1 level. Thus, reading only sometimes has the potential to raise a learner’s proficiency by at least one level on the CEFR.

The graph, Figure 1, run in Microsoft Excel, shows the test scores versus X7 (with values 0,1, and 2, corresponding to responses 0=never, 1=sometimes, 2=almost always). The dotted line is the tendency line, which provides the slope and the interception. This shows that as participants read more, they advance in proficiency. That is, the more the frequency of reading, the greater their proficiency as measured by the placement test.

Figure 1. Test scores versus frequency of reading for public school students.

Students from Private Schools

For participants who studied at private high schools, there were more factors which predict their scores, as seen in Table 5, which shows the significant variables of the multiple regression line. This answers our first research question in regard to students from private high schools.

Table 5. Multiple regression line of test scores for private school students

For students from private high schools, the factors which predict their scores are: length of time studying English (X1), having studied at a bilingual school (X3) (that is, with at least 10 hours of English instruction weekly, including content courses), having studied at a language institute (X4), having had private language instruction (X5), having lived in an English speaking country (X6), and how often they read in English (X7).

The regression line is:

As with participants from public schools, it can be seen that X7 has the greatest coefficient. That is, X7 has the highest influence on test scores.

The following graph, Figure 2, shows the test scores versus X7 (with values 0=never, 1=sometimes, and 2=almost always), for students coming from a private high school.

a. Dependent variable: TS (test scores)

Figure 2. Test scores vs. frequency of reading for private school students

Table 6 shows that the regression coefficient for X7 is statistically significant.

Table 6. Simple regression line for private schools in variable 7.

The simple regression line with independent variable X7, frequency of reading, is:

This means that a student coming from a private high school will increase his or her TS (test score) by 133.877 points, if s/he occasionally reads in English. A score of 405 is equivalent to a B1 level on the CEFR, while 538 is equal to a B2 level.

The mean scores on the placement test in public and private schools, considering the frequency of reading in the English language, are shown in the following Table 7. It can be seen that the averages in reading level 0 (i.e., those who never read) are very different between the two populations and private schools have a higher average. However, among participants who say they read in English all the time (reading level 2) the means are no longer very different. The explanation may be that, although private schools have more resources available, this advantage disappears when public school students read in English.

Table 7. Comparison of mean scores with regards to reading frequency

Once again, reading has the potential to improve proficiency by one CEFR level, though the gains for students from private schools are smaller than those for public school students. In the graphs below, test scores versus reading frequency, the graph for public school students shows that reading contributes considerably to improving the mean test score. This comparison responds to our second research question. Promoting reading among English language learners can help close the proficiency gap between students in public high schools and those in private high schools.

Figure 3 shows how students in public schools, if they read often, can achieve practically the same mean score on a proficiency test, as students from private schools do.

Figure 3. Side-by-side comparison of test scores versus reading frequency

Our study found that students from private schools scored significantly higher on the placement test than those from public schools. This is in line with previous studies (e.g., Davies, 2009; 2011; González Robles et al., 2004). Generally, in Mexico, students from private schools show greater English proficiency that those from state schools.

For students from public schools, the factors which showed greater effect on proficiency were how long they had studied the language, as also found by Muñoz (2015), whether they have taken extra classes at a language institute (Sayer, 2018), whether they have lived in an English-speaking country, and how often they read. This is in line with our own previous study (Santana, García-Santillán & Escalera-Chávez, 2017).

For private school students, the factors affecting proficiency were length of time studying the language, having studied in a bilingual school, having taken extra classes either at a language institute or with a private teacher, having lived abroad, and frequency of reading.

Length of time studying, extracurricular classes and having lived abroad all imply receiving more language input. As shown by Muñoz’s (2015) research, more input leads to increase proficiency. Parents in Mexico often enroll their children in extracurricular classes in language institutes to boost their learning and their future opportunities (Sayer, 2018)

For both groups of students, those from public and those from private schools, the factor which showed the highest coefficient (that is, the one which made the most impact) was frequency of reading. These results are consistent with other studies showing that reading helps improve language proficiency (e.g., Nakanishi, 2015; Robb & Kano, 2013). What is surprising is the degree of impact seen here. Reading in English has the potential to increase proficiency by one level on the CEFR, and the gain is greater for public school students than for those from private schools. This is important because attending a public school rather than a private school often depends on family income: state schools are tuition-free. Public school students do not always have the same opportunities for extracurricular classes or study abroad as those in private schools. Reading offers an inexpensive way bridge the proficiency gap between the two groups of learners. Creating a classroom library, with one book donated by each student, is more affordable for a family than extracurricular language classes, or study abroad. Yet, as this study shows, the impact on the student’s proficiency is greater.

Conclusions

This study examined the factors that lead to English language proficiency among students who are entering their first year of university studies in Mexico. The study was carried out in one large and three smaller cities in Mexico in the west, center, east and southeast regions of the country.

The study has shown how the amount of time a learner reads has significant impact on his or her language proficiency. Frequency of reading was an even greater predictor of proficiency than years of study or living in an English-speaking country. This is especially true for students who studied in state schools.

It must be considered that the study only shows correlation, and in no way seeks to suppose causality, yet given the results, it would be worthwhile to implement reading programs in language classes, especially in state schools.

Taking into account that students in public schools usually have limited resources, it is crucial to use those few resources to the fullest advantage. It is also important to consider that, generally, teachers have little control over the number of instruction hours they can offer, the choice of teaching methodology or textbook, the class size, or the resources that are available to them. They can, however, decide to devote some of their class time to implement an extensive reading program. Teaching students to enjoy reading and providing them with engaging materials that they can read on their own will go a long way in developing their language skills. The government, as well, should make a concerted effort to provide every school in the country with suitable reading materials. The results of this study show that this one, small change can have an important impact on their students’ learning.

Thus, the authors recommend the implementation of extensive reading programs in schools across the country. It is relatively easy to equip schools with small libraries of books that students can read, share, and enjoy. Regardless of location or socio-economic level, most students have some form of internet access, as well. Providing reading materials through the Mexican Ministry of Public Education (SEP) website is another option.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

The study purposely included students in diverse regions of Mexico because conditions vary from state to state. However, the four universities in the study are located in urban areas. A future study should be broadened to include rural schools, to see if the results shown here hold true.

The study was carried out in a country with certain characteristics regarding educational practices, including a gap between public and private education, class size, and teaching practices. As the literature shows, much of Latin America shares these characteristics. It would be unwise, however, to extrapolate results to other regions without further research, including replicating the study in other educational contexts and regions. Intervention studies to compare proficiency results among students participating in reading program, and those who are not, would also be very valuable.

Implementing a reading program to increase language proficiency among Mexican learners may not be easy. Varona Archer (2012) rightly states that, traditionally, Mexicans are not readers. But, as this study shows, including a program of extensive reading in English program has the potential to significantly increase students’ English language proficiency. At the same time, though, there is no reason to suppose that the skills acquired should only be in the English language. As students learn to enjoy reading, hopefully they will do so in their own language, improving their overall knowledge, as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Claudia Klauditz, Salvador Barrientos, Dr. Arturo García-Santillán and Myrna Balderas, who coordinated data collection at their respective institutions.

References

Basurto Santos, N. M., Gregory Weathers, J. G. (2016). EFL in public schools in Mexico: Dancing around the ring? HOW—A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 23(1), 68-84. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.1.297

Bamford, J. & Day, R. R. (Eds.) (2004). Extensive reading activities for language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Bonilla Jojoa, L. F. & Díaz Villa, M. (2019). Incidencia de factores socio-afectivos en el aprendizaje del inglés. [Incidence of socio- affective factors in learning English.] Revista de la Escuela de Ciencias de la Educación, 1(14) 49-64. http://hdl.handle.net/2133/15521

Bremner, N. (2015). Reculturing teachers as just the tip of the iceberg: Ongoing challenge for the implementation of student- centred EFL learning in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 39(3). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=752

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. (4th ed.). Longman-Pearson.

College Board (2019). English language assessment system for Hispanics. https://latam.collegeboard.org/elash

Dabarera, C., Renandya, W. A., & Zhang, L. J. (2014). The impact of metacognitive scaffolding and monitoring on reading comprehension. System, 42, 462-473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.020

Davies, P. (2009). Strategic management of ELT in public educational systems: Trying to reduce failure, increase success. TESL- EJ, 13(3). https://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume13/ej51/ej51a2

Davies, P. (2011). Three challenges for Mexican ELT experts in public education. Memorias del XII Encuentro Nacional de Estudios en Lenguas. Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala.

Dietrich, S. E. (2007). Professional development and English language teaching in Tamaulipas: Describing the training and challenges of two groups of teachers. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(2). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=978

de Almeida, R. L. T. (2016). ELT in Brazilian public schools: History, challenges, new experiences and perspectives. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(81). doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2473

Dörnyei, Z. (2014). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Routledge. Education First (2020, January). English proficiency index. https://www.ef.com.mx/epi

Gholami, R., Rahman, S. Z. A., & Mustapha, G. (2012). Social context as an indirect trigger in EFL contexts: Issues and solutions. English Language Teaching, 5(3), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n3p73

González Robles, R. O., Vivaldo Lima, J., & Castillo Morales, A. (2004). Competencia lingüística en inglés de estudiantes de primer ingreso a instituciones de educación superior del área metropolitana de la Ciudad de México. [Linguistic competency in English in incoming students to institutions of higher education in the metropolitan area of Mexico City] ANUIES-UAM.Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Guzmán Rodríguez, J. V. (2017). Social factors affecting second language learning: A study on internal and external variables. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Universidad de Jaén.

Huang, J. & Nisbet, D. (2019). An exploration of listening strategy use and proficiency in China. Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(1), 82-95. https://caes.hku.hk/ajal/index.php/ajal/article/view/586

López Montero, R., Quesada Chaves, M. J., Salas Alvarado, J. (2014). Social factors involved in second language learning: A case study from the Pacific Campus, Universidad de Costa Rica. Revista de Lenguas Modernas, 20, 435-351. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rlm/article/view/15077

Mitchell, R. & Myles, F. (2004). Second language learning theories (2nd ed.). Hodder Arnold.

Mora Vazquez, A., Trejo Guzmán, N. P., & Roux, R. (2013). Can ELT in higher education be successful? The current status of ELT in Mexico. TESL-EJ, 17(1). https://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume17/ej65/ej65a2

Muñoz, C. (2015) Time and timing in CLIL: A comparative approach to language gains. In M. Juan-Garau & J. Salazar-Noguera (Eds.) Content-based language learning in multilingual educational environments. Educational linguistics, vol 23, (pp. 87- 102). Springer.

Nakanishi, T. (2015). A meta-analysis of extensive reading research. TESOL Quarterly, 49(1), 6-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.157

Pamplón Irigoyen, N. E. & Ramírez Romero, J. L. (2013). The implementation of the PNIEB’s language teaching methodology in schools in Sonora. MEXTESOL Journal, 37(3). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=491

Porto, M. (2016). English language education in primary schooling in Argentina. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(80). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2450

Ramírez-Romero, J. L. & Sayer, P. (2016). Introduction to the special issue on English language teaching in public primary schools in Latin America. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(79) 1-8. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2635

Reilly, P. & Sánchez-Rosas, J. (2019). The achievement emotions of English language learners in Mexico. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 16(1), 34-48. http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v16n12019/reilly.pdf

Renandya, W. A. & Jacobs, G. M. (2016). Extensive reading and listening in the L2 classroom. In W. A. Renandya & H. P. Handoyo (Eds.), English language teaching today (pp. 97-110). Routledge.

Robb, T., & Kano, M. (2013). Effective extensive reading outside the classroom: A large scale experiment. Reading in a Foreign Language, 25(2), 234-247. https://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/October2013/articles/robb.pdf

Ruiz de Guerrero, N. Y., & Arias Rodríguez, G. L. (2009). Reading beyond the classroom: The effects of extensive reading at USTA, Tunja. HOW A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 16, 71-91. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4994/499450715005.pdf

Robillos, R J. (2019). Crossing metacognitive strategy instruction in an EFL classroom: Its impact to Thai learners' listening comprehension skill and metacognitive awareness. Asian EFL Journal, 21(2.2). 311-336. https://www.elejournals.com/asian- efl-journal/asian-efl-journal-volume-21-issue-2-2-march-2019

Santana, J. (2005). Moving towards metacognition. In M. Singhal & J. Liontas (Eds)., Proceedings of the Second International Online Conference on Second and Foreign Language Teaching and Research (pp. 126-131). The Reading Matrix Inc.

Santana, J. C. & Eccius-Wellmann, C. (2018). Gender differences in test anxiety on high.-stakes English language texts.Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 15(1), 100-111. http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v15n12018/santana.pdf Santana, J. C., Garcia-Santillan, A., & Escalera-Chavez, M. E. (2017). Variables affecting proficiency in English as a secondlanguage. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 6(1), 138-148. https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2017.1.138

Santana, J. C., García-Santillán, A., Ferrer-Nieto, C., & López-Martínez, M. J. (2017). Measuring attitude toward learning English as a second language: Design and validation of a scale. Journal of Psychological & Educational Research, 25(2), 165-182. http://www.marianjournals.com/files/JPER_articles/JPER_25_2_2017/Santana-et-all_JPER_252_165_182.pdf

Santana, J. C. & Ventura-Michel, K. M. (in press). A qualitative look at test anxiety and English language proficiency tests. The International Journal of Assessment and Evaluation 27(1). (in press).

Saville-Troike, M. & Barto, K. (2016). Introducing second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Sayer, P. (2015). “More & Earlier”: Neoliberalism and primary English education in Mexican public schools. L2 Journal, 7(3). 40- 56. https://doi.org/10.5070/L27323602

Sayer, P. (2018). Does English really open doors? Social class and English teaching in public primary schools in Mexico. System, 73. 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.11.006

Secretaria de Educación Pública. (2017). Estadística educativa: México: Ciclo escolar 2018-2019. [Educational statistics: Mexico. School term 2018-2019] http://www.snie.sep.gob.mx/descargas/estadistica_e_indicadores/estadistica_e_indicadores_educativos_15MEX.pdf

Serrano, R. & Muñoz, C. (2007). Same hours, different time distribution: Any difference in EFL? System, 35(3). 305-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.02.001

Varona Archer, A. (2012). Analyzing the extensive reading approach: Benefits and challenges in the Mexican Context. HOW—A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 19(1), 169- 184.https://www.howjournalcolombia.org/index.php/how/article/view/44

von der Embse, N., Jester, D., Roy, D., & Post, J. (2018). Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 483-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.048