Introduction

Textbooks have become increasingly important in today’s English teaching world. They can provide a structure to a course or a class. At the same time, they normally provide extra help with digital exercises, image banks or workbooks. On the other hand, textbooks are produced massively to cover as many countries or regions as possible. They are rarely designed for a specific country or region. Despite the possible advantages textbooks can provide, English teachers can sometimes find themselves working with materials that might not be relevant for their learners. Moreover, due to lack of training or time to plan, teachers can become just textbook deliverers (Crawford, 2002) increasing the risk of not contextualizing the content in textbooks.

Tomlinson and Masuhara (2013) suggest that designers of English materials have been making an effort to improve in many ways. They have tried to make the learning experience more personal and have implemented the advances of science in cognitive and affective challenge as well as applied corpus studies. Tomlinson and Masuhara (2013) also welcome the increasing use of global English as a way to make the learning experience a bit more realistic. Therefore, it is obvious that learning materials (textbooks especially) have improved and are trying to become a more efficient pedagogic tool for learning. Nevertheless, the same report also suggests that many authors were still trusting their intuition or previous textbooks’ success more than the latest research in materials development or second language acquisition. Another shortcoming was pointed out by Tomlinson (2013) who noted the need to create more engaging materials using content that can be more attractive to learners.

Several scholars have seen the discursive content of textbooks – not their pedagogical value – as a central topic of debate (Awayed-Bishara, 2015; Andarab, 2015; Andarab, 2019; Canagarajah 1999; Gray, 2013; Gray & Block, 2014; Melliti, 2013; Méndez García 2005). The question is if current teaching and learning materials are suitable enough to teach a language in a given context and if learners can relate to the topics suggested there. Current textbooks are, most of the time, produced massively to cover a wide geographical area and are not normally designed for a specific country or culture (Melliti, 2013). The problem of textbooks is not just geographical; it is rather ideological. A textbook represents a way to see the world (Awayed-Bishara, 2015), it is probably in many cases, especially in countries like Mexico, the window students have to the world of Englishes and therefore, it depicts the only view about English that some learners have access to (Norton & Pavlenko, 2019). As Gray (2014) suggests, textbooks are more than curriculum artefacts; they are of course used to teach English, but at the same time they become “cultural artefacts from which meanings emerge about the language being taught, associating it with particular ways of being, particular varieties of language and ways of using language, and particular sets of values” (p. 2).

Gray and Block (2014) hold that “quite apart from any methodological approach to language teaching and learning, at the heart of the ELT textbook is a regime of representation, a way of constructing the world that suggests what it means to be a speaker of English in the world” (p. 45). This representation is given from a perspective “which is socially situated and embedded in different discourses” (Risager, 2018, p.10). Gray and Block (2014) also state that this perspective is not accidental; it is usually arbitrary, selected and produced by groups which have a certain political and ideological view (p.46). Then, the textbook could be seen more as a cultural or ideological vehicle, rather than just a curriculum artefact. A textbook is discursively meaningful in many ways: it endorses life stories, visions, representations and positions that are reproduced through the global English language learning and teaching scenario. If they are the views of a writer, such views carry a particular vision about power imbalances regarding race, gender or sexual orientation (Gray, 2013). Minorities and vulnerable groups such as LGQBT (Lesbian, Gay, Queer, Bisexual and Trans), racialized groups, the disabled, the elderly or the working class, have been either erased from textbooks or voicelessly included, reproducing a very standard point of view and silencing others’ positions.

The danger of using textbooks where students might not find themselves and where they would just find a standard or neutral perspective is that we may reproduce, legitimize and perpetuate certain discourses that might undermine their identity or reinforce colonial positions. Apart from hiding other points of view, the risk is to deny students the right to be represented in their own learning materials and make them think they do not belong there, “a possible reminder that education is not for them” (Gray & Block. 2014, p. 46).

The purpose of this article is to identify misrepresentations of discriminated minorities in certain ELT materials and to present teachers with alternative ways to supplement textbooks.

Problematizing rather than just Mentioning

Even if the industry has tried to listen to different voices calling for recognition and representation of different vulnerable groups in order to make materials more realistic and fairer (Andarab, 2019), these have failed to represent all minorities faithfully. Some groups such as LGQBT communities, the working class, or the disabled, have been systematically erased from textbooks (Gray, 2013; Gray & Block, 2014; Seburn, 2017). On the other hand, racialized groups or the elderly have been generally poorly included, their issues are mentioned but they are barely problematized. Their representations are often stereotypical or portray a voiceless entity with no agency on their own issues (Awayed-Bishara, 2015; Gray, 2014). According to Fraser, to misrecognize the Other is not simply to think they are inferior but to create a situation in which they are “denied the status of a full partner in social interaction and prevented from participating as a peer in social life” (Fraser, as cited in Gray, 2013, p. 4).

To be included is a right that these groups have won; in contrast, to be included might not be enough when the struggle of a whole people is not discussed in depth. “Their point is that ‘mentioning’ is frequently tokenistic, the previously erased group gets a name check but the issues surrounding its erasure or its members’ struggle for recognition on their own terms is not explored” (Gray, 2014, p. 7). “On their own terms” carries here a significant meaning. The texts about minorities “fighting for recognition” are normally written in third person and the voices that are reproduced–even when sometimes they are not English as a first language (L1) speakers–are those of individuals in a privileged position who still conceive the Other as underdeveloped, in need of help, and desperate to be rescued (Gray, 2013). Thus, there are two main problems in reproducing this practice: the first is that minorities get silenced, and they cannot give their own version of the issues they live; and the second is that the voice that sees everything is that of an observer looking everything from a privileged perspective. It is creating a “we and they” vision in which, especially in developing countries, our students are trapped on the “they” side, being Othered by their own materials.

This article tries to present an alternative by rethinking discriminated ethnicities in another way. Therefore, it is necessary to show some examples of such representations in order to picture the problem and then, through the development of the model, show other possibilities of representing the Other. It is also important to mention that this article will focus on the representation of ethnic minorities and will not discuss in depth the other misrepresented groups because it is the author’s view that those representations should be treated differently (See, for example, Gray, 2013 or Seburn, 2017).

Examples of Under-representation in Textbooks

To briefly examine the representation of the Other in some English textbooks, I will take a post-colonial approach. Said (1978) and Spivak (1998) showed how those in power have historically misrepresented, in literature, history, and other fields, the different or distant cultures by depicting them as inferior in many different ways. Said (1978) states that no representation is exact as it carries a number of beliefs and is constructed by someone in a certain position. The author also argues that the West has systematically depicted an idea of opposition to the East, we and they, here and there, portraying Eastern cultural manifestations as inferior or uncivilized. Likewise, Spivak (1998) holds that representing should be rethought. Specifically, she argues that representation should be a form of political resistance, portraying individuals that are agents of their own change and voices that emancipate their community. Spivak and Said’s conceptualizations are helpful to analyze representations in English textbooks today.

The main problems of textbooks under-representing the Other can be divided in what Spivak (1998) called the three forms of Othering. The first form is how the powerful construct themselves as the ruling party by highlighting the differences between them and the Other. Inferiority is actually the second form of Othering and it is about portraying the Other’s characteristics as eccentric, problematic or uncivilized. The third form of Othering is about knowledge and how this and science are usually associated to the powerful and separated from the Other. Even if it is not a form of Othering in Spivak’s conceptualization, silencing voices is also very important to establish a superior group or individual to Others and, in the case of ELT, that these voices can never become a legitimate user of English. Therefore, the problem is not just that the vulnerable ethnicities’ voices are silenced, the problem is that they are never seen as likely, realistic, and positive models that an English learner can follow (Kikzckoviak & Lowe, 2019).

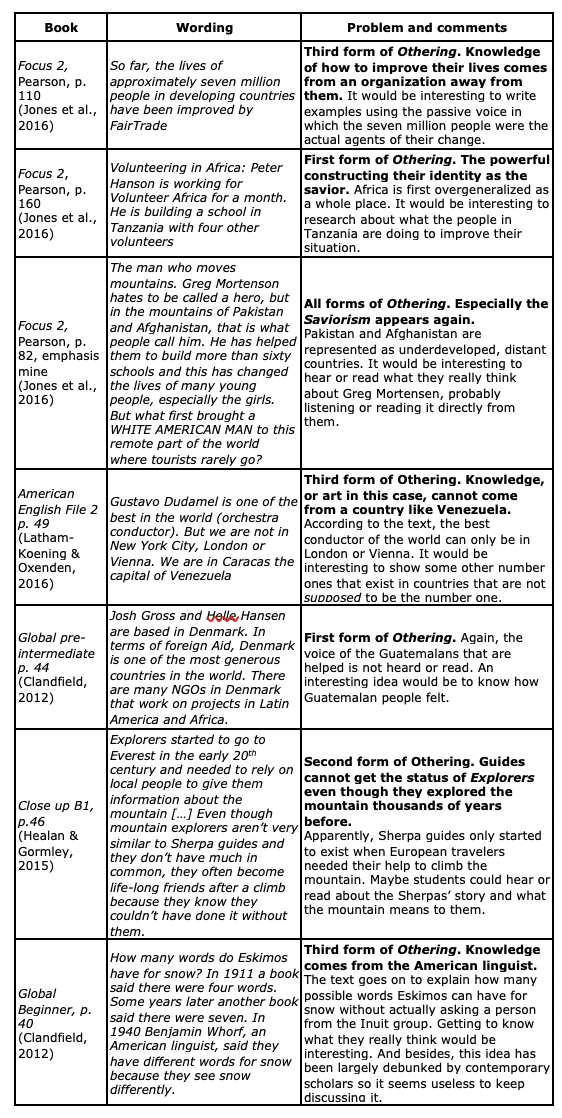

I analyzed four series of textbooks based on Spivak’s (1998) approach. The selection was made based on availability and the claim made by the four series that they were in support of multicultural communication; therefore, the materials are supposed to include other voices and represent them accurately. Table 1 (Representation in ELT textbooks) shows the wording (normally titles or sub-headings) found in some textbooks, the name of the textbook where it comes from and which of the three forms of Othering mentioned are found along with some comments of what a teacher can discuss in a classroom in order to challenge the subjective bias.

Table 1: Representation in ELT textbooks

Discourse Analysis: Critical and Postfoundational

For critical discourse analysis, text and talk can shape our reality in many ways (Van Dijk, 2015). Beliefs, positions, visions and ideologies are represented every day in our speech acts. Nevertheless, language can also challenge the reality we live in by incepting new ideas or concepts in our mind. Text and talk can do both tasks then: discourse can shape and construct a certain reality, but it can also challenge and resist it: “The actions we accomplish using language allow us to build (or destroy) things in the world, things like state history standards, marriages, or committee meetings” (Gee, 2011, p. 29). Among the various methodological and ideological views of discourse analysis, there is an approach that takes an explicit position in how discourse is analyzed. This approach “primarily studies the way social-power abuse and inequality are enacted, reproduced, legitimated, and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context” (Van Dijk, 2015, p. 466). Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) or Critical Discourse Studies (CDS) is a perspective rather than a method. Analysts under this umbrella term are fond of spotting the inequalities that are expressed through language in social relations. For this group of analysts, language is not only a way of communicating or describing the world, “In fact, critical discourse analysis argues that language-in-use is always part and parcel of, and partially constitutive of, specific social practices, and that social practices always have implications for inherently political things like status, solidarity, the distribution of social goods, and power” (Gee, 2011, p. 28).

Other researchers have tried to analyze not just the way domination is reproduced and legitimized, they have also researched how power is challenged, resisted and eventually deconstructed. “By investigating how people, texts and practices are dislocating apparently dominant discourse, and shaping change, a generative critique assembles participants who are already actively and productively critical, who are shaping new language and new worlds” (Macgilchrist, 2016, p. 267). This way of analyzing discourse, often called postfoundational or positive discourse analysis, also takes a position which pursues social justice as an ultimate end. However, postfoundational discourse analysis aims to look for possibilities of disruption and fissures in the structure that allow the power imbalances to be dismantled: “Analysing in this way entails seeking out examples of transformative discourse in order to critique the dominant and to build other worlds” (Macgilchrist, 2016, p. 267).

The form of discourse analysis that this article used for the model is critical discourse analysis, especially Gee’s (2011), which is expanded in the following part. However, I take the view that Macglichrist’s (2016) perspective of using a more generative approach is necessary to dislocate the arbitrary, weak and privileged constructed representations in some ELT materials. Therefore, Gee’s (2011) definition of CDA in combination with Macgilchirst’s (2016) perspective of discourse analysis are the two theoretical milestones of the model.

Gee’s Definition of CDA

The aim of discourse analysis is not to study structures or forms. It delves into how ideologies, positions and identities are reproduced through text and talk (Van Dijk, 2015). Gee (2011) holds that discourse analysis can be done in three different levels of analysis. The first stage, which he calls the utter-level meaning level, tries to analyze all the possible meanings–strictly grammatical or syntactical–of a sentence in a text: “In reality, they represent only the meaning potential or meaning range of a form or structure” (Gee, 2011, p. 27). If we take the phrase you are welcome, its meaning range is basically only two things: either someone is well-received in a place or someone is answering to thank you. That is the meaning potential it represents alone.

The second level is situated meaning, emphasizing that a certain context can possibly modify the meaning of a form or structure. If the same example is analyzed, I would be interested in where and how the phrase is mentioned. For instance, if the phrase is said as a response to someone who was not thankful, it can be concluded that the phrase would actually have the opposite meaning.

In the third level of analysis, the interaction participants’ features (status, political or religious views, and ethnicity) are also taken into account in order to see how these features shape or construct different meanings of a message. In the example above, it is necessary to see if the participants of the interaction are male-female, rich-poor, conservative-liberal and the power positions each interactant holds. For instance, if a politician pronounces the phrase in a public speech addressed to groups of immigrants, the intention of the politician is to show s/he is happy to have them around. On the other hand, if the phrase is uttered in a meeting with anti-immigrant associations, then the intention would also be very clear. Therefore, a series of endless implications can come up depending on the position, status, gender or ethnic group of participants in the interaction. This third level is what Gee calls critical discourse analysis (CDA) and his definition – situating the analysis in three different levels – will be very useful for the constitution of the model.

A CDA-oriented Model for Writing Materials to Debunk Weak Representations in Textbooks

CDA is interested in social problems (Van Dijk, 2015), it tries to explain and unmask the power imbalances that exist in society, by questioning naturalized practices like discrimination. The topics that are presented in textbooks do not reflect the complexity of a multicultural society (Gray, 2013). Tomlinson (2013) holds that it is important to vary materials in order to make them more meaningful for learners. He argues that by bringing up controversial and provocative topics that make the lesson more personal, students can better relate to their own learning (Tomlinson, 2013).

If textbooks are unable to reflect the complex context that some learners are surrounded by, it would be essential to use a different model to create materials that restore relevance and portray a more realistic view. The model that is proposed in this article is based on Gee’s (2011) definition and it tries to use text—either written or spoken—produced by a member of a vulnerable group, in this case from an under-represented ethnicity. The model uses discourse analysis techniques; this means that learners will be involved in doing discourse analysis at a very smooth level. The three levels described by Gee will be expanded to create reading or listening comprehension activities that get learners to critically engage in discussions after having read or listened to a different voice giving their own perspective of a situation.

The activities will normally, not imperatively, follow Gee’s (2011) definition of CDA levels in order to go from a very textual analysis, probably the kind of analysis students are used to doing, to a more contextualized one, to finally focus on more political and complex implications of the linguistic choices made by the producers or interactants of the text. Therefore, each text will contain an utter-level meaning task, a situated meaning task and a critical discourse analysis one.

It is important to remember that a postfoundational perspective is used, that is why only generative analysis is done to build stronger and at the same time more positive constructions of under-represented minorities. Texts emphasize the possibilities of challenging power structures through the use of language and show how this creates the options to restore social justice and seek for a better world. The following examples try to respond to some of the examples of misrepresentations given above. All of them follow the principles of the model; the text comes from a member of a vulnerable group, giving a voice and restoring their agency, but at the same time showing that members of these groups could be models to follow. There are three tasks, according to Gee’s levels of analysis, which accompany learners so they can develop their critical skills. There is also a wrap-up activity at the end in which learners can give their own opinion about the topic mentioned.

Example 1

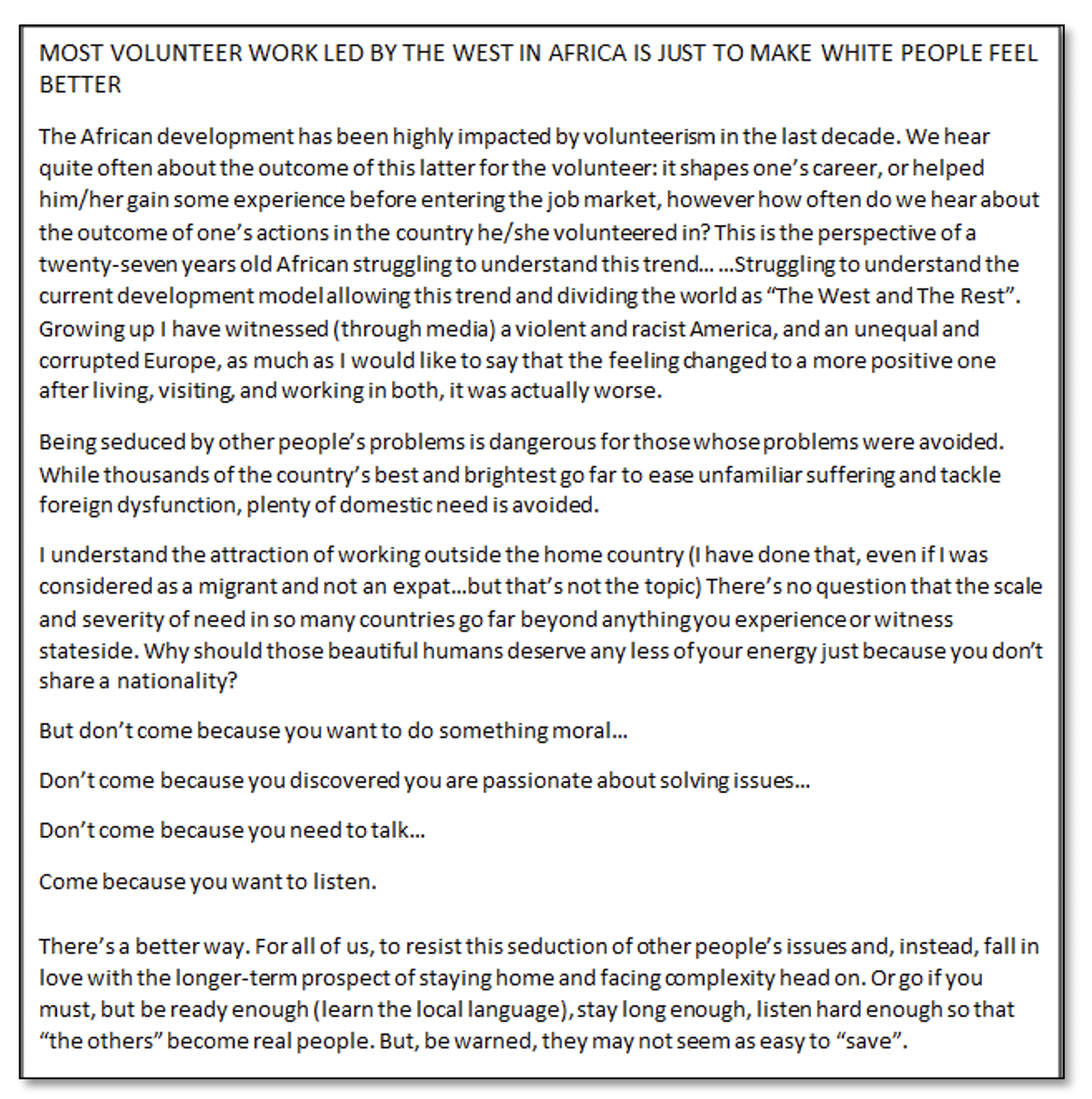

The first text is adapted from a blog post online that openly exposes volunteerism as a form of just making white people feel better.

Figure 1: Fragment of a blog.[1]

1. Utter Level Meaning Task: Can you identify if the following phrases found in the text are orders? Write Yes or No.

- Being seduced by other people’s problems is dangerous.

- don’t come because you want to do something moral

- go if you must

- We hear quite often about the outcome of this latter for the volunteer

- stay long enough

2. Situated meaning task: Read the following sentences from the text and decide who the author is referring to in the words in bold. Then, discuss with a partner who are generally we, you and they in the text.

- don’t come because you want to do something moral

- they may not seem as easy to “save”.

- But don’t come because you want to do something moral…

- For all of us

- Come because you want to listen.

3. CDA level task. Who has the power in the following dichotomies? Where does the author want to situate White and African people? Where are they really? Discuss with a partner.

Listen-speak

Learn-teach

Help-being helped

Go-welcome

Save-Being saved

4. Reflection activity: Where would you place yourself? Would you like to be a volunteer? Would you like foreigners to come to your country?

Comments: By giving another perspective of the situation, learners get to reflect on the idea of volunteerism. At the same time, the activity debunks the construction of a people in need of being saved as in the examples given above in the article. The CDA level activity tries to shed some light on who has the power in the dichotomies, the person who listens or the person who speaks, the individual that teaches or the ones that learn from them. The activity aims to show that the author seeks to give the power back to African people by situating white volunteers on the passive side of the dichotomies. The activity makes students reflect on the value of volunteerism and question their own biases on the topic. It also seeks to build a much stronger and combative representation of African people in this case.

Example 2

This second example might be a way to supplement or complement the textbook analyzed in previous stages. It shows another way to approach the Inuit people by analyzing how they resist and challenge power.

The Inuit Women Manifesto

We are the Inuit. We are a group that inhabits several countries including Canada, USA (Alaska), and some parts of Russia, Norway and Finland. We were commonly known as Eskimo for hundreds of years but we didn’t like it.

Because of climate change and other political problems, we have been pushed to go south losing our lands and with them our traditions like our folk music or dance. Violence was very common against us to force us leave our lands.

In 2004, the Inuit Women Association created a manifesto enlisting what Inuit people and governments should do to stop violence against us. Some of the important points of the manifesto are:

- Stop any kind of violence against us

- Don’t touch our children, they are the future

- Act now or we won’t have a chance tomorrow

- if you governments really care, do something

- Adopt this manifesto, post it, share it![2]

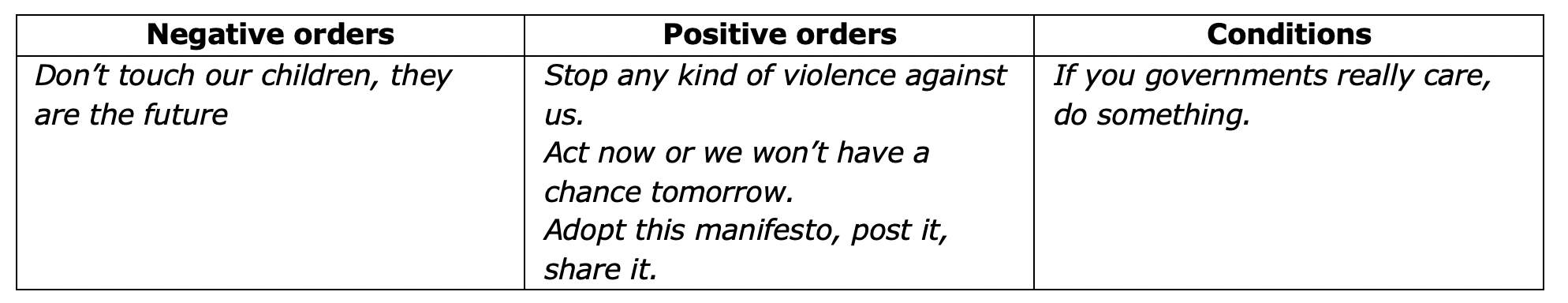

Utter level meaning task: Organize the manifesto points in the following three columns. (Target student responses are included in the table.)

Table 2: Utter level meaning task.

Table 2: Utter level meaning task.

2. Situated meaning task: Work with a partner and decide who is supposed to receive each message. Look at the example.

1. Stop any kind of violence against us.

a. The other Inuit people b. People and governments attacking them

2. Don’t touch our children, they are the future.

a. People hurting them b. People reading the manifesto

3. Act now or we won’t have a chance tomorrow.

a. Other Inuit people b. Inuit children

4. If you governments really care, do something.

a. Governments of Canada or USA b. Governments of Inuit communities

5. Adopt this manifesto, post it, share it!

a. Governments b. People reading the manifesto

3. CDA level task: When you read the manifesto, how do you imagine the Inuit Women? Choose three adjectives from the list and add one more you want. Compare with a partner and explain your choice.

____ Strong

____ Weak

____ Combative

____ Problematic

____ Independent

____ Bossy

____ Easy-going

____ Introvert

____ Authoritarian

____ Free

_______________ (your own idea)

4. Reflection activity: Write your own manifesto.

- Consider what you think it is important to defend in your background (nature, traditions, language, uniqueness)

- Write at least five sentences

- Share it with the class

Comments:

The activity constructs a much more realistic representation of Inuit people by giving them a voice and highlighting their agency on their own issues. By getting learners to read the manifesto, they realize that this ethnic group, especially women, are organized in resisting the dominant structures that have been pushing them for a long time. The CDA level activity aims to get students to think what kind of people write a manifesto, weak or strong? Combative or authoritarian? When learners get to reflect on this, they realize that Inuit people are not just a subject to study about, they are real people trying to confront their problems.

Conclusions

This concept-based article depicts a model and its operationalization on how to deconstruct embedded under-representations of vulnerable ethnicities in ELT materials. It gave a short overview of how the ELT publishing industry has fallen short in giving everybody, especially those learning the language, a voice in textbooks. After that, it showed how critical, and especially postfoundational, discourse analysis conceives the use of language in political and social contexts. Two examples were given in order to facilitate the understanding of its operationalization.

The model was conceived to give a voice and their agency back to discriminated people. Because of this, the characteristics of text and talk to serve as input are:

- The author or one of the interactants of the text should be a member of a vulnerable group

- This author or producer of the message is also portrayed as a model to follow

- They give their own opinion or perspective of a controversial or interesting social issue in which they are somehow involved

- The texts try to supplement a textbook lesson by showing a different perspective of a vulnerable, yet a strong and active group.

The kinds of tasks in the model are based on Gee’s (2011) definition of critical discourse analysis that highlights three different levels of analysis:

- Utter level meaning task. A task in which the meaning range of certain phrases is examined and provides just a literal meaning to the text

- Situated meaning task. This task connects the language with the context in which it was produced, in order to give learners more elements to understand the meaning of the text

- CDA level task. It tries to show how, through language, the producers of the text are resisting, challenging or deconstructing dominant structures that have made their people seem passive in other ELT contexts.

The model seeks to remedy the power imbalances embedded not just in learning materials, but in the whole ELT world. It is of no surprise to mention that the materials produced massively are just a reflection of what happens in the whole scenario. Unfortunately, the power imbalances highlighted in this article are also present in the working conditions, the published research or the conferences given, to count a few.

It seems to me that, in order for our profession to meet the challenges of globalism in a deeply meaningful way, what is required is no less than an epistemic break from its dependency on the current West-oriented, Center-based knowledge systems that carry an indelible colonial coloration (Kumuravadivelu, 2012 p. 14).

By starting to change one of the clearest dependencies that the rest of the world has, that of the textbook as an authority because it was written by someone that knows best, other possibilities could arise.

The importance of breaking the epistemic dependency on Center-based textbooks can hardly be overstated. Clearly, textbooks should reflect the lived experiences teachers and students bring to the classroom because, after all, their experiences are shaped by a broader social, cultural, economic, and political environment in which they grow up (Kumuravadivelu, 2012 p. 21).

The teaching and learning of English should, in my view, move on to where the actual language is going: a world-size set of possibilities, with different views, different styles and above all, different people learning it. Giving and receiving only one perspective of the world is tedious and opaque. The world today is diverse and full of colors, full of voices and perspectives.

Integrating and taking advantage of the development of new and diverse linguistic fields, such as discourse analysis, should be more relevant to tackle the issues that have been left out for decades in the subject. Discrimination should be openly discussed in classrooms in the world, especially in language learning classrooms that seek to build understanding and bonding among cultures.

The model presented above is an option to bring up the topic, to start discovering other points of view, to question our own biases and to help teachers find an alternative to face the complex issues that can arise in the world today.

References

Andarab, M. S. (2015). Representation of the characters in the claimed English as an International Language-targeted coursebooks. Studies in English Language Teaching, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.22158/selt.v3n4p294

Andarab, M. S. (2019). The content analysis of the English as an international-targeted coursebooks: English literature or literature in English? Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 14(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v14i1.3930

Awayed-Bishara, M. (2015). Analyzing the cultural content of materials used for teaching English to high school speaker of Arabic in Israel. Discourse & Society, 26(5), 517– 542. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0957926515581154

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford University Press.

Clandfield, L. (2012) Global: Beginner. Macmillan

Clandfield, L. (2012) Global: Pre-intermediate. Macmillan

Crawford, J. (2002). The role of materials in the language classroom: Finding the balance. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.) Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge University Press.

Méndez García, M. del C. (2005). International and intercultural issues in English teaching textbooks: The case of Spain. Intercultural Education, 16(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636310500061831

Gee, J. P. (2011) Discourse analysis: What makes it critical? In R. Rogers (Ed), An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education (2nd ed., pp. 23-45). Routledge.

Gray, J. (2013) Introduction. In J. Gray (Ed.), Critical perspectives on language teaching materials. Palgrave Macmillan

Gray J., & Block, D. (2014). All middle class now? Evolving representations of the working class in the neoliberal era: The case of ELT textbooks. In N. Harwood. (Ed.) English language teaching textbooks, (pp. 45-71). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, V., Kay, S., & Daniel, B. (2016) Focus 2. Pearson.

Kikzckoviak, M., & Lowe, R. J. (2019) Teaching English as a lingua franca. Delta.

Kumuravadivelu, B. (2012). Individual identity, cultural globalization and teaching English as an international language: The case for an epistemic break. In L. Alsagoff, S. L. McKay, G. Hu, W. A. Renandya (Eds.). Teaching English as an International Language: Principles and Practices (pp. 9-27). Routledge

Healan, A., & Gormley, K. (2015). Close-up:B1 (2nd ed.). Cengage-National Geographic

Macgilchrist, F. (2016). Fissures in the discourse-scape: Critique, rationality and validity in post-foundational approaches to CDS in Discourse & Society, 27(3), 262 –277. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0957926516630902

Melliti, M. (2013). Global content in global coursebooks: The way issues of inappropriacy, inclusivity, and connectedness are treated in Headway Intermediate. Sage Open, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244013507265

Latham-Koening, C. & Oxenden, C. (2016) American English File 2. Oxford University Press.

Norton B., & Pavlenko A., (2019) Imagined communities, identity, and English language learning. In X. Gao (Ed.) Second handbook of English language teaching. Springer.

Risager, K. (2018). Representations of the world in language textbooks. Multilingual Matters.

Said, E. W. (1978) Orientalism. Pantheon Books

Seburn, T. (2017). Use of debates about LGBTQ+ in ELT materials (2017, 27 November). 4C in ELT Tyson Seburn. http://fourc.ca/debate-lgbtq

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.) Marxism and the interpretation of culture, (pp. 271–313). Macmillan Education.

Tomlinson, B. (2013). Introduction: Are Materials developing? In B. Tomlinson (Ed.) Developing materials for language teaching.Bloomsbury.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, T. (2013). Adult coursebooks: A survey review. ELT Journal, 67(2), 233-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct007

Van Dijk, T. (2015). Critical discourse analysis. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds). The handbook of discourse analysis, (pp. 486-504). Wiley.

[1] Retrieved from: https://afropunk.com/2016/11/op-ed-most-volunteer-work-led-by-the-west-in-africa-is-just-to-make-white-people-feel-better

[2] Adapted from the Nunavik Inuit Women Manifesto, retrieved from http://www.chaireconditionautochtone.fss.ulaval.ca/documents/pdf/Saturviit_Long-study-report.pdf