Introduction

The researchers’ major concerns are to find the best curricular and pedagogical tools, ideas and resources to fruitfully engage all kinds of learners outside the classroom regarding Foreign Language Learning and Teaching (FLLT). Throughout history, learners’ engagement has been thought to be “focused upon increasing achievement, positive behaviours, and a sense of belonging” (Parsons & Taylor, 2011, p. 4). The individual differences in learning styles and diversity have had a crucial role in students’ academic path. If we consider this in light of the fact that students have changed “over the last twenty years; perhaps as a result of technology-rich upbringing, they appear to have ‘different’ needs, goals, and learning preferences than students in the past” (Parsons & Taylor, 2011, p. 6), our duty as teachers is to fulfil their ‘new’ needs. Since most Higher Education students belong to the so-called Net Generation, they need “self-directed learning opportunities, interactive environments, multiple forms of feedback, and assignment choices that use different resources to create meaningful learning experiences” (Barnes et al., 2007, p. 2). These Net-Geners want more practical, active and inquiry-based methodologies and resources to learn and are less eager to accept what they are offered (Hay, 2000). This more independent trend in learning style has been developed from the Net-Geners’ acquired habits of searching and getting all kinds of information and data from the internet.

As stated by Parsons et al. (2019), it has been said that there are “two learning worlds – those of the “real” world and the classroom – and for some time these two worlds failed to suitably collide” (p. 144). That is why, for decades, instructors and schools have tried to update their educational system and have worked together to provide students with multiple learning environments enhanced by new technologies. This is particularly necessary these days regarding the current worldwide situation we are going through in the educational field because of the COVID 19 pandemic. The teaching community is searching for technology-based resources to keep on carrying out their classes so as not to leave any student behind.

All this said, the thesis set in the present article is that the Communicative English Language Skills Improvement Programme (henceforth CELSIP), created for this project has explored and gathered user-friendly, technology-based tools and other motivating and meaningful resources to learn EFL autonomously. This has entailed to find a helpful tool to work in an online environment as the COVID situation has forced educators to do so (Dhawan, 2020). Therefore, learners practice and explore English as a foreign language (EFL) in an autonomous way outside the classroom, which justifies the need for the present study. Thus, the objective of this research is to present the design and evaluation processes of a new inclusive and technology-and-autonomous mediated tool named the Communicative English Language Skills Improvement Programme (CELSIP). Hence, it is described here an in-depth analysis of the data drawn from the participants’ responses gathered from a semi-structured questionnaire and their one-course-work self-assessment written testimony. One of the outcomes of the implementation and analysis of this programme will be an enhanced version of the CELSIP, grounded on the analysis of data to be used in the following stage of the project.

Literature Review

The CELSIP programme

The CELSIP (see http://hdl.handle.net/10550/69580) programme, which stands for “Communicative English Language Skills Improvement Programme”, is a technology-based tool which seeks to provide students with enough resources, mostly technology-based (Armstrong, 2018) to satisfy students’ learning styles while improving their linguistic competencies in EFL (Dhawan, 2020). This is so because students have need of different instruction since as they are diverse so are their needs. Herrera and Murry (2016) supported this idea by defining different teaching methods that should be taken into consideration to accommodate diverse students’ individual needs. The CELSIP is based, on one hand, upon McKenzie’s (2005, 2012) standards of promoting learning through the effective and appropriate use of technology while students are working assorted professional skills suitable for their future careers (Nicolaidou et al., 2021). On the other hand, the CELSIP sets its foundations on technology-driven learning since “technology can be a motivating and interactive tool, providing a source of real language, both written and spoken, in the classroom and motivating learners to produce more language than otherwise they might have done” (Stanley, 2013, p. 2). Moreover, “the gradual evolution of specialist design studio learning spaces from conventional physical studios to a blend of virtual and online educational environments […]” (Marshalsey & Sclater, 2018, p. 65), has also encouraged the authors of this research to increase autonomous learning in Higher Education.

The CELSIP was created and evaluated at the Department of Language and Literature Teaching (English) from the Faculty of Education of the University of Valencia (Spain) (Soler Pardo & Alcantud-Díaz, 2020). It was a complementary and lifelong-learning language training programme. The CELSIP was tested in the subject Foreign Language II (English) of the Primary Education Teaching Degree (English). The specific objective of this programme was to help pre-service teachers achieve a higher communicative level in EFL by developing the knowledge, abilities, and necessary tools to become autonomous, competent, and better communicators in the English language. The programme also looked to consider their diverse types of learning and their potential as disseminators of their acquired knowledge to their future students.

This learning tool (Soler Pardo & Alcantud-Díaz, 2020) is divided into three parts, the first one provides a wide range of thematic sections made up of a series of working tools, tips, and strategies on how to use them to obtain a better performance, by empowering multi-intelligence in learning English. The second section is a student follow-up reflective logbook the aim of which is to invite learners to write their reflections and experiences as a way of critical thinking upon their own learning process. The last part of this programme covers the self-evaluation section, based upon the descriptors of the Common European Framework of Reference for Language Learning (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2018) and the GSE[1] (Global Scale of English, Pearson) for levels B1 and C1. Therefore, all the skills related to the course planning of the subject previously mentioned were included in this part. The students had to carry out a self-assessment by pointing at those descriptors, also called “can-dos”, that they were accomplishing throughout the project to make them reflect and become aware of their progress.

The CELSIP is composed of a series of multimodal, multiliteracy, and mostly technology-driven tools. Multimodal tools are those that combine two or more modes such as written, spoken, or visual texts (The New London Group, 2000; Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). The tools were organized according to the following sections (Soler Pardo & Alcantud-Díaz, 2020): Our best TV series to learn English; Films and popcorn!, Listen to music & sing along as if you were a Grammy winner!, Useful Apps to improve your English; Why not (board) games; Just read it,; Time for audiobook, Talking opportunities, and The news, talk shows & other educational websites in English. All the materials chosen to be part of the programme were justified. Therefore, most of the sections offered provide speech, body positioning, and gestures to students. They get scaffolding through different semiotic resources that help them to interpret the situations they are watching. These signs and modes are the ones used to communicate in a multimodal context.

Different kind of learning and multimodal resources

As Kress and Bezeemer (2016) explain, multi-modality is related to the resources used for making meaning and how different mediums affect what is being communicated. Thus, every encounter with a wide range of scenarios of the world that TV series, talk shows, videos, and films, to mention just a few, entails learning. Furthermore, films can be more comprehensible than written texts since they enable viewers to absorb content more efficiently in a multimodal way (Bateman & Schmidt, 2012). In regard to listening to music and singing along, it has been shown so far by scholars (Karabulatova, 2021; Stansell, 2005) that music can help in the improvement of grammar and vocabulary learning. Through CELSIP, some songs have been considered appropriate for the students to practise different accents such as the difference between American and British accents through singers from both nationalities or for the sake of vocabulary learning. Additionally, the researchers considered that an educational technology section would be paramount, so, the Useful apps to improve your English section was created. In it, students could learn and practise with their mobile phones at any time, in any place.

The next tool added was a classic: (board) games. Learners could improve their language skills through a series of traditional games that are familiar to them (e.g., thinking games such as Scattergories[2] or card games such as Storycubes[3]) as well as many digital ones (Kuo & Chang, 2019; Valenza et al., 2019). One of the essential tools in the CELSIP was the reading section or Just read it! A language learner has to acquire reading habits to improve and maintain their linguistic level. That is why, under this section, students are invited to read a series of books, either in hard copy or digital format. that the authors of this article consider might appeal to them while teaching some specific vocabulary or expressions in the target language. In the same way, students are suggested to combine reading with listening, so that while they are improving their grammar skills and gaining vocabulary, they are also improving their pronunciation through listening to audiobooks (Alcantud-Díaz, et al, 2014) all in an inclusive environment. Additionally, speaking has been the neglected skill in the classroom for a long time, which is why the learners were requested to listen to certain sources online (e.g., English Accent Coach[4], Forvo[5], etc.). Finally, listening to the news, talk shows and other educational websites have also been suggested in the CELSIP so that the students could be autonomous learners able to find a complementary way to learn English as a foreign language with these instruments.

Technology and multiple intelligences

The CELSIP, as mentioned previously, settles its foundations on technology-based resources while the instructional framing aims to be its core. The authors are aware of the fact that many educational institutions pressure their teachers in terms of innovation and information and communications technology (ICT). This makes them sometimes be mesmerized by technology, overshadowing educational instruction and even methodology. So, merging the Multiple Intelligence framework with technology-based activities can offer significant link with learning to promote and enhance the English learning process (Armstrong, 2018). In addition, as McKenzie (2005) states, without an educational scaffolding:

instructional technology will not fulfil its promise. It will, instead, fall by the wayside like other innovations that have preceded it. In this regard we have come full circle: technology supports the accommodation of multiple intelligences in the classroom, while at the same time, MI theory offers a strong theoretical foundation for the integration of technology into education. (p. 7)

The arrival of the Internet to students’ lives has made technology vital and immediate for them, to the point that students do not visit web sites anymore unless they are asked to. They are focused on social media which provides them a quick response. Apprentices use their mobile phones not only for studying and learning, but also to communicate, research, listen to music, play, watch TV series, do some sport, and so on. The problem is that students seem, most of the time, to be blind to knowledge due to the attraction of technology. Thus, according to McKenzie (2005, 2012), the only way to be sure that ICTs are going to be successful in the learning process is “to make sure that they are well-grounded in educational theory, thoughtfully implemented theory, thoughtfully implemented, and then, carefully reflected upon” (p. 38). In this regard, one stratagem that we include in the CELSIP was to support different kinds of learners by putting in contact their particular skills with different technological resources suited for their diverse learning styles (Armstrong, 2018). Those resources are framed in a well-thought-out teaching methodology composed of the tools, tips to make the best of them, and self-reflection and self-evaluation sections, as mentioned previously. It is, as Gardner (2011) puts it, “not how smart you are, but ‘how’ you are smart” (p. 12).

Thus, teachers should deal with different ways of learning in their classes to accommodate diversity, inclusion, and multiple intelligences. That will lead us to Gardner’s (1983, 1993, 2000, 2011) theory on multiple intelligences. Gardner (1991) stated that “students possess different minds and therefore learn, remember, perform, and understand in different ways” (p. 11). Some studies such as that of Ahvan and Pour (2016) showed that some of the multiple intelligences propounded by Gardner (1983, 1993, 2000) (e.g., visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal, logical-mathematics, kinaesthetic, musical and naturalistic) have an important connection with students’ outcomes. In that respect, it is important for teachers to “prepare the learning environment which includes learning media, which supports the development of multiple intelligences” (Sudarma et al., 2019, p. 1) to achieve success in the classroom. Though, as Sudarma also points out, few teachers dedicate time to include these kinds of intelligence in the class and only two are present: verbal-linguistic and logical-mathematics.

Emphasizing multi-intelligence empowerment is crucial for students to explore the abilities and the intelligence(s) they have. Thus, taking Sadiman et al.’s model (2006) as a reference, the authors intended to create a “multiple intelligence-oriented learning media” (p. 2), which puts forward a novel idea in learning specifically, 2) allow learners to interact with the media, 3) develop several intelligences at the same time (e.g., mathematics and spatial), 4) allow learners to identify their own intelligences (Sadiman, et al., 2006).

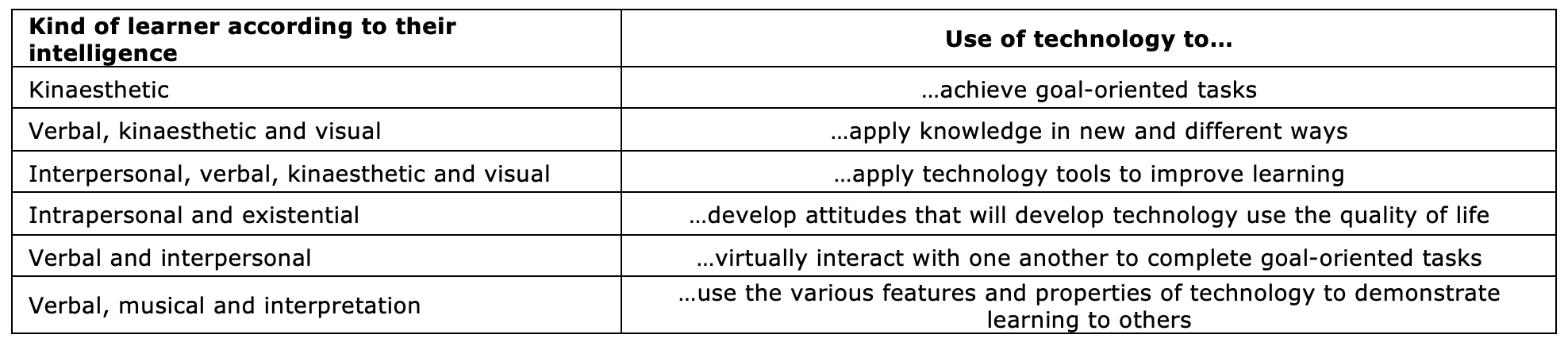

Through this process, students are expected to reflect upon their progress, their strengths. and weaknesses. This is the main core of the CELSIP, to explore what the different learners need and, thus, present a series of activities based on technology which could adjust their needs. According to McKenzie (2005), the different learners will make use of technology for different learning purposes. Some examples are shown in table 1 below:

Table 1. Appropriate use of technology according to Multiple Intelligences theory (McEnzie, 2005, p. 32)

The authors consider it relevant to explore learners’ interests and likes in order to create exercises that are always appealing to them, ensuring that the proposals programmed guarantee all students’ learning. Along these lines, the section dedicated to watching films and TV series was aimed at visual learners, and the music and sing-along tools were aimed to attract musical-learners; the useful apps and (board) games section was designed for those students with both logical-mathematical intelligence – since they experiment, reason, and resolve puzzles – and linguistic intelligence. The reading section was thought out for those with intrapersonal intelligence, since they could study through books, also reinforces verbal-linguistic intelligence. The last section deals with speaking and was aimed at those students with not only verbal-linguistic intelligence, but also with bodily-kinaesthetic and interpersonal intelligence since they have to interact with others.

With all this said, it seems to be a need of using technology-based self-learning EFL materials based upon the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2018). The Multiple Intelligences theory (Gardner, 1993, 2011) is a significant framework to develop technology-based activities and resources created for autonomous learning (Armstrong, 2018, McEnzie, 2005). Thus, the role of learning materials, resources, and strategies, to motivate autonomous learning, should be linked to students’ multiple intelligences and daily habits (related to the use of mobile devices) to get them engaged in the learning process (Armstrong, 2018). Hence, the purpose of this study is to show that the CELSIP is a useful and motivational programme that will help students explore different options for EFL autonomous learning that suits their least and most developed intelligences (Armstrong, 2018).

Methodology

The method of the present article is an interpretative qualitative case-study approach (Duff, 2014) that was adopted to allow a deeper insight into the CELSIP’s implementation. This is so, since this study leans towards a sociocultural framing, “paying attention to the various ways in which learning and performance are mediated, performed, and understood” (p. 236). This method has offered an effective way of measuring the usefulness and efficacy of this learning tool. Thus, our intention here was twofold: first, to evaluate the effectiveness of the CELSIP (see the literature review) as an autonomous learning tool. Second, to enhance the CELSIP of the CELSIP grounded on the analysis of data gathering after testing the programme with the participants.

Participants

This study involved 49 pre-service students in their fourth year of a Teaching of English in Primary Education Degree. The authors selected this group of students because they were about to start their professional careers as primary school English teachers and, thus, they could apply all the knowledge learned during this project. Since these participants were students in the researchers’ classes, they were informed about their participation in the present study. Regarding their linguistic competence, the participants had an average level of B2/B2+ according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). This study was carried out obtaining verbal informed consent from the participants since they were not going to be identified.

Instruments

An empirical mixed-method data collection process was conducted for the present research. Regarding the first stage of the research, in-depth information on the students that took part in the pilot project was collected through a semi-structured interview. All the questions included in the interview were aimed at exploring the opinion of the students regarding the potential and efficiency of the CELSIP as a technology-based, autonomous-learning programme.

The second data collection tool used in the present research was learning outcomes, the CELSIP written handouts, namely, the self-assessment written testimonies of the participants. Regarding the semi-structured interview, it was aimed at gathering the participants’ self-reported attitudes and opinions to measure the construct of the present research. The validity of these interviews was content wise, related to the semantics and grammar, since in the view of the researchers it included questions which covered all aspects of the construct being measured, the usefulness of the programme at stake and its reliability. The interview was composed of the following questions: 1) General opinion about CELSIP; 2) What were your favourite tools? 3) What other tools have you used? 4) What do you think about the Tips for a better use part? 5) Have you used some of them which you didn’t use previously? 6) About the reflection part. How have you used it? And 7) What about the self-assessment part?

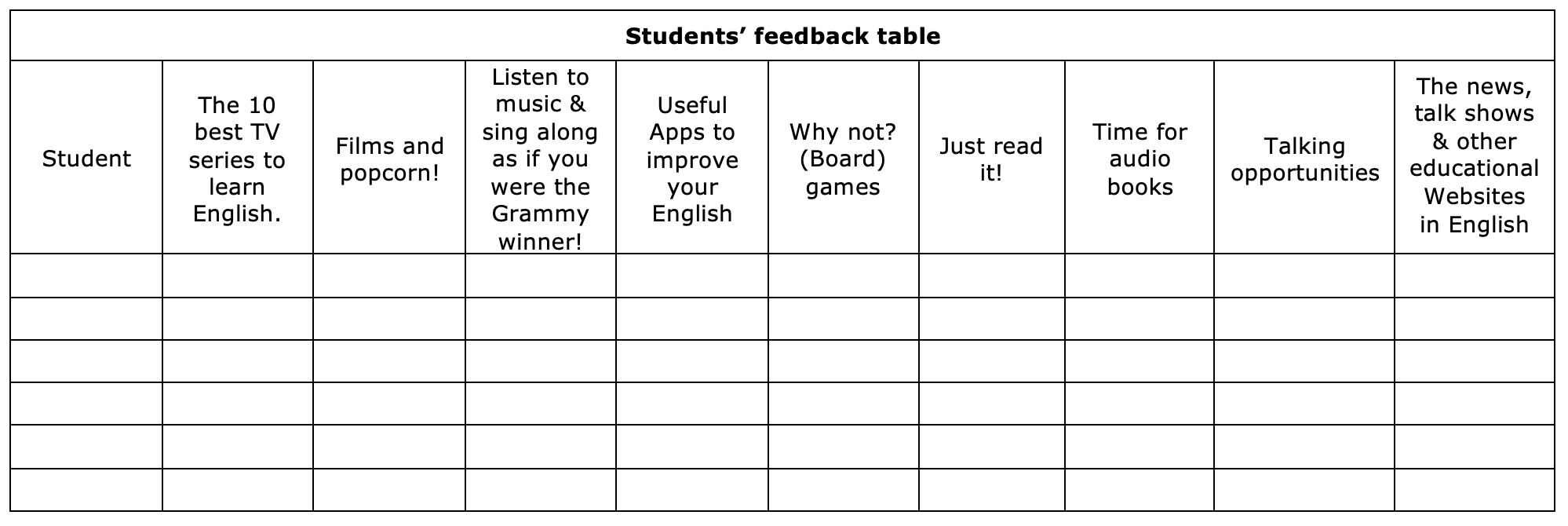

Concerning the analysis of the written testimonies, all the information was transcribed to Table 2 to be coded and assessed.

Table 2. Analysis table for the participants’ written testimonies

Procedures

The students used a printed version of the CELSIP at the beginning of the term. They were encouraged to make use of it during the whole term (four months) provided feedback, answered questions, were motivated to use the tools and resources proposed (as described in the review of literature) and wrote on the CELSIP self-reflection and self-assessment sections. Then, the semi-structured interview was carried out in face-to-face session at the end of the term through oral interaction with the researchers. The students, who had to take the CELSIP printed version with them to check their responses, were interviewed in pairs so they could interact between them. The interviews were recorded and stored for further transcription and analysis.

Once the interview was over, the participants were asked to hand in their CELSIP handouts so as the researchers could scan and analyse in depth their self-assessment written testimonies. These testimonies, together with the interviews data, were collected to be transcribed, reduced and analysed following a qualitative paradigm s to get results for the researchers to interpret.

To analyse all the data collected from the interview, a grid segmented by thematic axes (the different questions) was created. For each interview, the fragments corresponding to each dimension were separated. The data provided by the participants that stood out for the study (throughout the analysis) was highlighted and extracted to draw conclusions. A similar procedure was carried out with their self-reflection testimonies in which the most important data was highlighted and collected.

Results

The most significant data for our research was extracted from the grids mentioned and analysed by comparing the records of the categories (questions) to be researched, which allowed the authors to refine the concepts as shown in the following paragraphs.

Students’ feedback based on their written opinion on the CELSIP handout

Of the study population, 49 individuals completed and returned the CELSIP handout to be analysed. This section of the research aimed at looking for information regarding three main fields: First, to know students’ opinions for and against the different sections, the materials and the recommendations proposed by learners. Second, to focus on their suggestions in terms of adding new materials to the programme in order to create a further enhanced version of the CELSIP. Finally, the researchers read their self-learning reflection to enhance the instruction, if needed, for further implementations.

Opinion on the tools included in the CELSIP

The data regarding the tools that were most students’ favourites, on average, pointed to TV series, films and music, followed by Apps, talk shows and games. Listening to audiobooks and reading were the least popular. Regarding TV series, it was interesting to read that many students used to watch most of the series in Spanish versions and because of the CELSIP tips, they had started to watch them in English with subtitles in that language. Furthermore, they had learnt a lot of vocabulary and expressions, either in British or American real English. One interviewee said, “Since I had started to watch TV series in English I could not change the language because it felt more real.” As another student mentioned: “I started to watch [TV series] with Spanish subtitles and when I got used to the sound of English I started to use English subtitles.” Some of the students reported having used an online dictionary to interact with the TV series by repeating and imitating the accent while watching. Most of the participants reported having learnt many expressions, slang, idioms, informal language, terms (e.g., food names, medical or war terms, and so on), phrasal verbs, differences between Spanish and English jokes, and that had improved their pronunciation and fluency. They also had learnt to recognise different English accents. To do so, they had repeated the expressions they found interesting or challenging; to re-watch some parts just in case they had missed something; to practice with TV series in English that they had already seen in Spanish; to follow those pieces of advice on using a logbook to write down what they did not know, understand, or which called their attention.

Opinion on the selection of materials

TV series and films

Concerning the selection of materials, one informant reported that “Sherlock Holmes was an interesting TV series because I had learnt current English cultural references and also some from the past.” She also added that it would be interesting if this list of materials “proposed less known series […] and putting others could help to expand resources and catch the interest of those who have already seen the most popular ones.” This participant added that “TV series ha[d] helped me to become more fluent in English and to use more expressions when she spoke in English.” Even though the information regarding films was quite similar to that collected related to the use of TV series, there were some differences. Some participants were fonder of films than of TV series since, as talking about this issue an interviewee said: “they only take a couple of hours” while watching a whole TV series took much more time; that is, “they are less time consuming than the series.” Along this line, some participants suggested they preferred to watch films that they had already watched in a Spanish version because “it is convenient to know the story”. They realized some pragmatic uses of language learning, as this following comment illustrates: “there is a big difference when it is in the original version, for example, the jokes are funnier in the original one.” Some films have particularly been highlighted related to the participants’ professional future, such as The King's Speech, because “it can teach about learning and speaking difficulties and prepare future teachers.” Some suggestions on recent additions to the CELSIP version 2 were also provided, such as Divergent, Saga and Love Actually (differences between American and British accent and expressions). The most interesting observation to emerge from the data gathered was the potential inclusion of some musicals such as Pitch Perfect, Mamma Mia, and Bohemian Rhapsody because “it is a musical and through the songs it is easier to practice.”

Learning through music

Once the music issue was brought onto the scene, it turned out that this tool was one of the most motivational and inspiring ones. Students had sung everywhere, in many languages and with different purposes, as it can be seen in this example provided by one informant who had used: “LyricTraining with my roommate as a competition. The one who sang correctly won and the other one had to wash the dishes.” The students had repeated the songs over and over again, used Spotify[6] every day, written down and learnt expressions and vocabulary through songs, learnt the lyrics of the songs by playing (e.g., filling in the gaps or contests of the correct lyrics between friends). Moreover, they had sung through karaoke versions in YouTube to see if they could pronounce the words correctly. Some of them provided significant data such as: “I am keen on music since a very young age, then I was learning lyrics by heart and that has been proven beneficial for my English skills”, “music is a background noise that helps me to have higher exposure to the language. I found music useful for collocations and vocabulary and teaching about life.” Solely one more suggestion was provided regarding music: Sazhaim App[7] (it helps to learn foreign songs).

Learning through APPs and games

Concerning Apps, we found out that participants either hated or loved them, there was no middle-ground. As one student put it: “Apps are quite boring or offer basic knowledge to me”, after two weeks of using them, many of those apps required paid subscriptions. Among the most used apps, there were online dictionaries such as Wordreference[8]and Fluentu[9]. This was the section where more suggestions for future improvement of the programme was found. The reason for this was that these tools were related to the use of their mobile devices.

Games were a discovery for most participants who were teaching private lessons, since they used them in their classes with children, but had not realized that they could also serve as a learning tool for them, even for those with auditive and visual diverse needs in the classroom (Valério Neto et al., 2019). The most popular games were the traditional ones, that participants had played all their lives. They knew many others that were using in their classes or playing at home.

Learning through books and audiobooks

The section devoted to reading showed mixed results. About 50% of the participants did not read traditional books for their age, beyond those that were compulsory for a particular subject. Even, some of them mentioned the fact that they had just read websites in English or they had read a series of books that were for children because they were easier for them to understand and the topics were fun too. Some participants loved literature and reading since, as one participant put it: “I read in English for not losing the essence of the plot” or, “As a university student I started to read in English not only books but also the news”. All of them agreed that books and articles had helped them to improve grammar skills, vocabulary, and writing, even though not all of them were very fond of reading. Some students mentioned that the list of books provided in the CELSIP had made them read in English some books that they had read in the past in Spanish.

As mentioned before, audiobooks were the least popular among the participants since most of them did not know them as a learning tool. As one participant commented: “Audiobooks seem a bit difficult or not that interesting”, or another one “Still have not used any of audiobooks but there is an interest”. Even though they understood the convenience of audiobooks, some of them were committed to starting using them and the rest of the group “preferred to read traditionally” as one student put it. There were some examples of spare moments in which some participants used audiobooks “I listen to audiobooks before the exams, although I don’t like audiobooks so much.”

Talking opportunities

The Talking opportunities section opened a wide range of possibilities for the participants. They had been partaking in a telecollaboration programme named Tandem Through Skype and even though it had not been included in the list the entire group proposed it to be included. This programme is out of the scope of the present article, but to pinpoint it, we could say that it is aimed at improving fourth-year students’ linguistic and intercultural skills while having some fun meeting new people of their age from foreign universities. Apart from this activity, participants had used Elsa speak[10]and suggested including tips such as having Whatsapp and Skype video calls with foreign friends in English, to make English the prime language of all their mobile devices, going to pubs where multilingual encounters were organized. They also suggested new tools such as Cleverbot[11].

Learning with news, talk shows and other educational websites

Concerning the news, talk shows and other educational websites in English section, the most popular shows among the participants were TED talks videos in YouTube. They provided them not only English practice but also some knowledge about educational issues, Vaughan radio, reading the news in English online daily, and YouTube videos in English. The Ellen DeGeneres Show was the most watched. The suggestion for further incorporation in the program was RTE-TV channel in which different accents can be heard and different cultures saw. James Corden´s or Jimmy Fallon´s shows, BBC and Jessica Kellgren-Fozard’s channel were some new suggestions.

Semi-structured interview with participants.

The second method used to identify the effectiveness and suitability of the CELSIP involved a semi-structured oral interview with 49 participants. Respondents were asked to: (a) give a general opinion about the CELSIP; (b) say what their favourite tools had been; (c) explain what other tools they had used; (d) give their opinion about the tips provided for better performance and efficiency of the learning results; (e) say how they had used the reflection part; and (f) explain how they had used the self-assessment part. The interviews were conducted by the trainer-interviewer, carried out in pairs and recorded for a better analysis, obtaining a 4.083-hour recording.

A general opinion about the CELSIP

The first question was aimed at providing a general opinion about the CELSIP. The overall response to this question was very positive (85.72%) since the total number of responses described the programme: (very) useful (61.22%), (very) interesting idea (14.28%), a good tool to motivate or to encourage to do more things regarding their English competence daily (8.16%), 14.28% were DK answers. Focusing on the details of the positive opinions, over half of those surveyed reported that they had lacked enough time to work on the programme as they would have liked, because of the overwhelming workload they had to face in the fourth year. Twenty-one participants reported not to having been attracted by talk shows, audiobooks or games as self-learning tools, as many of them were not even to have been aware of their existence as such. As one interviewee said: “The first time I was given the CELSIP I was surprised by the number of resources that we had available and the first thing I did was to read everything and then figure out what things I was already doing to improve my English and what things I could implement.” Talking about this issue an interviewee said: “There are a lot of resources and I appreciate them because maybe I am not able to find them by myself. It is important to find so many resources, so we could choose.” There was significant positive feedback from all the participants regarding (i) the closeness to their needs and likes of the recommended materials and (ii) the fact that the CELSIP provided them with a framework to work in the future.

In turn, some participants expressed the belief that CELSIP was in line with some of the practices they had previously had in terms of their hobbies: “I’ve always thought that using music and films and TV series you can have almost perfect pronunciation. In my case, I have always listened to music and series and my friends didn`t and that is what made the difference, maybe they knew more grammar than me but in the pronunciation part, I was better because of the music.” Also “We usually play games in Spanish and it is nice to have a different variety in another language”; “I liked the idea because it was like having a different view of what we do every day. Like taking into account what we normally do but being aware of what how can we learn”; “I’ve never heard about audiobooks and it seems a great idea to listen to an audiobook while I’m doing something else and I want to try while doing sports so you can do both get fit and practise English”.

Participants’ favourite tools

The second question was about the students’ favourite tools. In response to that question, 89.79% of those surveyed, 44 participants, said that TV series and films were their favourite tools. Within this group, apart from TV series, nineteen students also showed music as their favourite tool, three participants pointed also at YouTube videos, two mentioned Apps, one of them added books, and another one included papers online. Regarding the other members of the sample: 4.08% of them mentioned only songs as their favourite; 2.27% revealed being their favourite songs and films (one student), and the same percentage was related to talking shows and games (2.27%, one student each answer).

Other tools used by participants

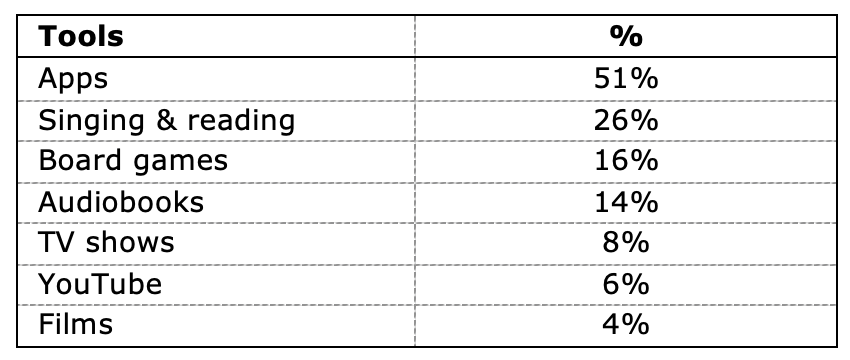

Question 3 gleans information about what other tools the participants had used, as explained in Table 3.

Table 3. Question 3. Other tools used by the participants

In response to the question, Apps were the most tried tool, it was mentioned 25 times, followed by singing and reading (13 mentions each); board games (8), audiobooks (7); TV shows (4); YouTube (3), and films (2). The majority of those who responded to this item felt that the tools they had used were related to their way of being, their habits and their free time. What caught our attention in regard to this data is that they are directly related to the differences existing among the varied kind of learners. As this participant put it, “I tried audiobooks but they are not my thing because multitasking is not for me. I prefer some repetitive tasks” or like another one put it: “audiobooks or apps are not for me because you can work on with them while waiting for the bus or doing something else but I need to be focused on just one thing”.

Opinion about the tips provided for better performance and efficiency of the learning results

Question 4 relates to participants’ opinion about the tips provided for better performance and efficiency of the learning results. It is also related with if they had used some of the tips which they had not used previously. Most of the participants had focused mainly on songs and TV series tips and had added some to their daily habits when listening or watching them. Some cases in point were the following: looking at the lyrics and singing out loud, watching the TV series with subtitles in English, becoming one of the characters and trying to talk simultaneously, miming the accents, and taking notes on new vocabulary or expressions. Other responses to this question shed some light once more on the fact that not all the tools, nor even the learning tips provided were devoted to many learners, like one of them explained: “I felt embarrassed with some of them [tips] because I’m very shy. Even when I’m alone. The rest are useful”. Another example was the participant who “tried to follow the subtitles at the same times but it got on my nerves because it was hard at the beginning but now I can do it. I am more fluent”. Two of those surveyed reported that the learning tips were nothing new since they had been doing similar things all their training life.

The reflection part

Regarding question 5, related to the way they had used the reflection part of the CELSIP, many issues were identified, twenty-four students used that section as a reflection part as suggested by trainers. An example could be seen in this excerpt from one of the interviewees: “I have chosen that TV series because of the collocations and phonology (I had to struggle with it). I haven’t learnt too much from sitcoms such as How I met your mother or Big Bang Theory because they are current situations and I already know the vocabulary.” Nevertheless, only thirteen participants used it as either a vocabulary or TV series or songs list and twelve out of the 49 students did not use it at all.

The self-assessment part

Finally, question 6 was related to the description of the way participants had used the self-assessment part. The overall response to this question was poor since students just mentioned whether they had used the self-assessment section at the beginning or the end of the term. Nevertheless, some participants’ comments were in themselves the essence of what the researchers of this article wanted them to learn: CELSIP “gives words to what you cannot explain on your own because I wouldn’t express this that way, but if I read it I know I have achieved it or not. You get some metalanguage because it is really academic” or “At the end. I have realized that I can do a lot of things, but I didn´t tick some of them because I was still improving, but they were like in progress.”

Discussion

CELSIP: An improved version

As mentioned previously, the researchers have in a way created a second version of the CELSIP considering students’ suggestions and comments. Some of these changes implied removing certain Apps which our learners found too easy for their level (e.g., Duolingo[12]) and add two new sections (e.g., Get subscribed and Videopportunities), which we considered appropriate according to the students’ level and interests.

The changes fulfilled in the new version of the CELSIP programme were based upon the participants’ suggestions and include a few more updated TV series such as You (2018); A Discovery of Witches (2018); The Crown (2016); Thirteen Reasons Why (2017); Orphan Black (2013); Downton Abbey (2010); Vikings (2013). In addition, a selection of new films has been also added in to awake students’ interests. These are: The Parent Trap (1998); Mamma Mia (2008); Into the Woods (2014); Bohemian Rhapsody (2018); Frozen (2013); Mamma Mia! Here we go again (2018); Slumdog Millionaire (2009); and Beyond Blood (2016). Regarding the section ‘Listen to music & sing along as if you were the Grammy winner!’ the digital music app Spotify has been included. Also, a wide range of apps to be used as teaching instruments for EFL learners has also been incorporated to the programme. Some examples of these are Wlingua[13], AnkiDroid[14], Lyrics Gap[15], and Quiz your English[16].

Concerning games, a new interesting game called Xeropan[17] has been included. A few new readings thought to be appealing for the students’ age and level have been added: (a) Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; Matilda; James and the Giant Peach; The Witches; or (b) Caroline Kepnes’ Hidden Bodies. Then, Whatsapp via Google Now Voice, another instrument to improve English in tandem called Seagull Tandem Project[18] and, a Skype tandem activity led by the teacher in class to help students improve their linguistic and intercultural skills were also added. The Graham Norton Show, where music and comedy are involved, was added to ‘The News, talk shows & other educational Websites in English’ section.

In addition, the self-assessment section has been modified following students’ requests regarding this section. Thus, an extra column called ‘in progress’ and a ‘how to work with this part’ section have been added to give students more opportunities to express their achievements and to understand what they are requested to do. A list of ‘Life Competencies’ was included: critical thinking; collaboration; learning to learn; communication; creative thinking; and social responsibilities.

Our study has raised some important questions about online learning environments, and the use of educational technology aimed at students with different intelligence and diversity to learning EFL and adapt digital component to specific learning goals to prove effectiveness. Further, we have analysed data gathered from students’ comments and reflections.

Concerning the use of the CELSIP and its suitability and accuracy for the sake of learning online and by different learners, we can confirm firstly, that the CELSIP is a very useful tool in diverse ambits: (a) as a self-training tool, since the learner’s autonomy is given by the flexibility and availability of technology and that strikes directly on their motivation at the time of studying on their own; (b) as a bridge to their hobbies and free time activities, because of the closeness to their needs and likes of the recommended materials that the CELSIP offers. That is, all the activities that they could carry out were within their grasp; (c) as long-life learning and teaching tool, since the CELSIP provided them with a framework to work in the future since the participants were pre-service teachers of EFL. Along with these terms, some of the participants showed their interest in ongoing work to keep on improving; and d) as a very useful source of materials for online lessons.

In terms of a second issue, the wide range of tools in the CELSIP suited the multiple intelligences of the participants. For example, those who thought to be more visual, were more interested in TV series, films, YouTube or music (since they were working with it through YouTube channels). The kinaesthetic ones were keener on apps and games. But also students’ special needs have accommodated here, for instance, visual diversity was provided with tools such as music, audiobooks, online games and TV programmes or films. Students with auditory impairment could use books, APPs, films or TV series with subtitles, games and so on.

In the third place, the final self-assessment has worked as an indicator of those areas they might keep in touch with to look for the right tool and tip to fill it. This assessment has put these future Primary Education Teachers of English in touch with the new CEFR (2018) by having to deal with terms such as reception, production, and mediation.

In brief, the results show that the programme elaborated and implemented with the students has helped them improve the skills suggested, and increase their self-esteem and motivation to work autonomously. Furthermore, since the results drawn from this research provided an enhanced version of the CELSIP, a more fitted-to-different-learners online didactic toolset on the gathered data, students were given voice to take part in the design of the updated version.

Implications

The pedagogical implications for practice are:

- that the students who took part in this research were able to “learn to learn” following the 21st Education long-life-learning guidelines when they got used to working with the CELSIP.

- they also got ready to transfer the developed competencies to their future Primary Education learners.

- in addition, the CELSIP could play an important role in addressing the issue of how technology can be used to overcome the existing problems derived from diversity as Armstrong (2018) states.

Conclusions

This study has presented the design and evaluation processes of a new inclusive programme named CELSIP, a project that copes with different learners, and that is technology-and-autonomous mediated learning. The evaluation process has been described here by showing an in-depth analysis of the data drawn from the participants-in-the-CELSIP pilot programme’ responses gathered from a semi-structured questionnaire and their one-course-work self-assessment written testimony. This research has shown that, according to the thesis set, the CELSIP has provided user-friendly, technology-based tools and other motivating and meaningful resources to learn EFL autonomously no matter what kind of learner participants were. The second major finding was that this programme has served online as the COVID situation has forced educators to do (Dhawan, 2020).

This study has also provided an enhanced version of the CELSIP, a more fitted-to-different-learners online didactic toolset based on the gathered data. However, this study was limited in terms of the reluctance of most students to follow a steady pace to engage in the CELSIP all over the pilot period (Alcantud-Díaz & Soler Pardo, 2020). In addition, the different quality of the mobile devices has also been a drawback for this research. More broadly, research may also be needed to explore first, a more detailed analysis of students’ achievement concerning the scores obtained in the oral exam both in 3rd and 4th year of the subjects Foreign Language I (English) and Foreign Language II (English) to scientifically prove their learning achievements. Second, further research shall examine the implications of implementing the CELSIP in other educational institutions (future Primary centres) by the undergraduates taking part in this study.

References

Ahvan, Y. R., & Pour, H. Z. (2016). The correlation of multiple intelligences for the achievements of secondary students. Educational Research and Reviews, 11(4), 141-145. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2532

Alcantud-Díaz, M., Ricart-Vayá, A., & Gregori-Signes, C. (2014). ‘Share your experience’. digital storytelling in English for Tourism” Ibérica 27. 185-204. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4730576.pdf

Armstrong, T (2018). Multiple intelligences in the classroom. (4th ed.). ASCD

Bateman, J., & Schmidt, K. (2012). Multimodal film analysis: How films mean. Routledge.

Barnes, K., Marateo, R. C., & Ferris, S. P. (2007). Teaching and learning with the Net Generation. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 3(4). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/104231

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(3), 164-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544800903076044

Council of Europe (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR). Retrieved from: https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Education Technology Systems, 49(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0047239520934018

Duff, P. A. (2014). Case study research on language learning and use. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 34, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000051

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1991). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach. Harper Collins.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2000). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for 21st century. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). The unschooled mind. How children think and how schools should teach. (3rd ed.). Basic Books.

Hay, L. E. (2000). Educating the Net Generation. The School Administrator, 57(54), 6-10.

Herrera, S. G., & Murry, K. G. (2016). Mastering ESL/EFL methods: Differentiated instruction for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Karabulatova, I., Ldokova, G., Bankozhitenko, E., & Lazareva, Y. (2021). The role of creative musical activity in learning foreign languages. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100917

Kress, G., & Bezemer, J. (2016). Multimodality, learning and communication. A social semiotic frame. Routledge.

Kuo, R., & Chang, M. (2019). Guest editorial: Guidelines and taxonomy for educational game and gamification design. Educational Technology & Society, 22(3), 1–3. https://drive.google.com/open?id=11arSoJxhlBHlcofqwTuPCh1XLWNhFXw5

Marshalsey, L., & Sclater, M. (2018). Supporting students’ self-directed experiences of studio learning in Communication Design: The co-creation of a participatory methods process model. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(6), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4498

McKenzie, W. (2005). Multiple intelligences and instructional technology (2nd ed.). International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

McKenzie, W. (2012). Intelligence quest: Project-based learning and multiple intelligences. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

Nicolaidou, I., Stavrou, E., & Leonidou, G. (2021). Building primary-school children’s resilience through a web-based interactive learning environment: Quasi-experimental pre-post study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/27958

Parsons, D., Inkila, M., & Lynch, J. (2019). Navigating learning worlds: Using digital tools to learn in physical and virtual spaces. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3675

Sadiman, A. S., Raharjo, R., Haryono, A., & Harjito (2006). Media pendidikan, pengertian, pengembangan, dan pemanfaatannya[Educational media, their understanding, development, and use]. PT Raja Grafindo Persada.

Soler Pardo, B., & Alcantud-Díaz, M. (2020). A SWOT analysis of the Communicative English Language Skills Improvement Programme: A tool for autonomous EFL learning. Complutense Journal of English Studies, 28. https://doi.org/10.5209/cjes.63845

Stanley, G. (2013). Language learning with technology: Ideas for integrating technology in the classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Stansell, J. W. (2005). The use of music for learning languages. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Sudarma, I K., Suwatra, I. I., & Prabawa, D. G. A. P. (2019). The development of multiple intelligence empowerment-oriented learning media at elementary schools. INA-Rxiv. https://doi.org/10.31227/osf.io/n7tpc

Parsons, J., & Taylor, L. (2011). Improving student engagement. Current Issues in Education, 14(1), 1-33. https://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/745

The New London Group (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. (pp. 9-37). Routledge.

Valenza, M. V., Gasparini, I. & Hounsell, M. da S. (2019). Serious game design for children: A set of guidelines and their validation.Educational Technology & Society, 22(3), 19–31. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1jHb1P4pEmEL143vIWeO0klUPxmEOQLii

Valério Neto, L., Fontoura Junior, P. H. F., Bordini, R. A., Otsuka, J. L., & Beder, D. M. (2019). Details on the design and evaluation process of an educational game considering issues for visually impaired people inclusion. Educational Technology & Society, 22(3), 4-18. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1frRNoS8oM_MhQDm1XgsdSSqxqPONQv4G

[1] See Global Scale of English | Global English language standard | Pearson English

[2] https://scattergoriesonline.net

[3] https://www.storycubes.com/en

[4] https://www.englishaccentcoach.com

[6] https://www.spotify.com/es

[7]https://www.softplanet.co/shazam?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI45r3ofLl9gIVA5BoCR1MQwWvEAAYAiAAEgIZWPD_BwE

[8] https://www.wordreference.com

[11] https://www.cleverbot.com/app

[13] https://english.wlingua.com

[14] https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.ichi2.anki&hl=en&gl=US

[15] https://www.lyricsgaps.com

[16] https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/learning-english/games-social/quiz-your-english