Introduction

Extensive reading is an approach to, not just reading, but language learning that emphasizes the reading of large quantities of material which is usually graded in both the lexis and syntax used, so that students can read quickly without the use of a dictionary. The basic purpose of ER is to allow the students to practice the language in order to build up automaticity, to make the vocabulary and syntax that they already know more familiar and to expose them to additional contexts where it is used. See Day & Bamford (1998) for a comprehensive definition. [1]

Extensive reading has long sat in the doldrums of language pedagogy. While many respected scholars over the years have acknowledged its utility, few teachers have, in fact, implemented ER in their classrooms. According to the Annotated Bibliography of Works on Extensive Reading in a Second Language (Extensive Reading Foundation) , an ER approach was espoused by German and French teachers in the United States as early as 1919 (Handschin 1919; Hagboldt 1925), but the pedagogy failed to attract a following due to one important deficiency: no graded or simplified texts. This was recognized by Bagster-Collins (1933) “We need a number of texts all on the same level, all employing largely the same basic vocabulary.” (p. 156). The 1940s was the “Army method” era concentrating on basic communication, while the 1950’s and 1960’s was mired in the audio-lingual approach with its structuralist roots and emphasis on automatic production of uncontextualized syntactic patterns.

Towards the end of the 60s Longman launched the Longman Structural Readers, with MacmillanRanger series following shortly afterward. Even with the surge in publications, however, ER attracted only a small following. David R Hill, with the EPER (Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading 1992) Project was responsible for its popularization in Malaysia and Tanzania (Hill & Thomas (1998). Day & Bamford (1998) surveyed the many reasons why the ER route is “less traveled”:

- The work required to set up a program, and,

- The difficulty of finding time for it in an already crowded curriculum

- The dominance of the reading skills approach…

- The believe that reading should be delayed until students can speak and understand the second language

- Confusion between extensive reading and class readers. (p. 46)

Research in the effectiveness of ER

The Annotated Bibliography of Works on Extensive Reading in a Second Language lists over 500 articles related to the theory and implementation of Extensive Reading. As is the case with much SLA research, it has been difficult to assess the effectiveness ER since it is normally used as additional means of language study outside of class, which means that the students in-class study confounds the research, thus making it difficult to attribute gains to the outside reading alone. Studies such as Stokes et al. (1998), Renandya et al. (1999), Mason (2006) and Lee (2007), however, have empirically demonstrated the effectiveness of reading large volumes of text as an aid to language acquisition.

MoodleReader for tracking student reading

The MoodleReader software described in this article helps to overcome on of the major stumbling blocks to ER implementation by providing a solid mechanism for students to demonstrate that they have read their graded readers, while at the same time obviating the need to squeeze ER into a crowded curriculum or to “sell” the approach to a cohort of resistant teachers. The program is currently being used by over 50 schools, from elementary level through adult/university which are mainly in eastern Asia, but with a smattering of schools on all continents.

Assuming that a sufficient number of graded readers are available and that it is implemented in a course that is required for graduation, the program allows curriculum-wide implementation by fiat – read, or else! Naturally, the overall result will be enhanced if the instructors are familiar with ER and pre-disposed to use it, but our experience has been that teachers are slowly won over as they start to implement the approach and see the resulting change in attitude among their students.

What I offer below did not come about by plan, but rather as a fortuitous side effect of the efforts of the English Department in the Faculty of Foreign Languages to find a better way to assess whether its students had done their assigned graded reading. The software we developed was intended to replace “Accelerated Reader” which we had been using, but which had become increasingly unworkable. [2]

The MoodleReader program worked well with our 120 first year English majors in 2008 when I slowly came to the realization that the same system would probably work equally well with our 3000 non-majors, virtually all of whom were required to study English in their first year at the university. Since one of my “hats” was Chair of the General Education English Curriculum Committee, it was easy to get the committee, all of whom are ELT specialists, to agree to my suggestion of curriculum-wide implementation. I suggested the following plan:

- Require all instructors to include a uniform Extensive Reading requirement in their course descriptions,

- Have them pass out information to their students in the first week of classes that described the purpose of ER, the course requirement and how they were to go about it, and

- Supply each instructor, at the end of the term, with a full report of the ER performance of their students, with a grade to be factored into their class evaluations.

The plan was carried out in the April 2009-March 2010 academic year and went relatively smoothly. While only about 60% of the students actually read one or more books, some students far exceeded our modest goal of 5 books per term. Nevertheless, pre/post-test comparisons for the April 2009-March 2010 and the previous April 2008-March 2009 which contained a cohort of students of identical ability, showed a very significant gain in their reading proficiency. A forthcoming article will describe the experimental statistics in depth.

Description of the MoodleReader Software

MoodleReader is, strictly speaking, a “module” that can be easily integrated into a Moodle site. The module, once installed, allows the site manager to download quizzes from a central server (http://moodlereader.org) where there are currently about 850 quizzes available for graded readers, basal readers (used with native speaking children) and popular “Youth Literature” such as Judy Blume’s books, the Baby-Sitters, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew.

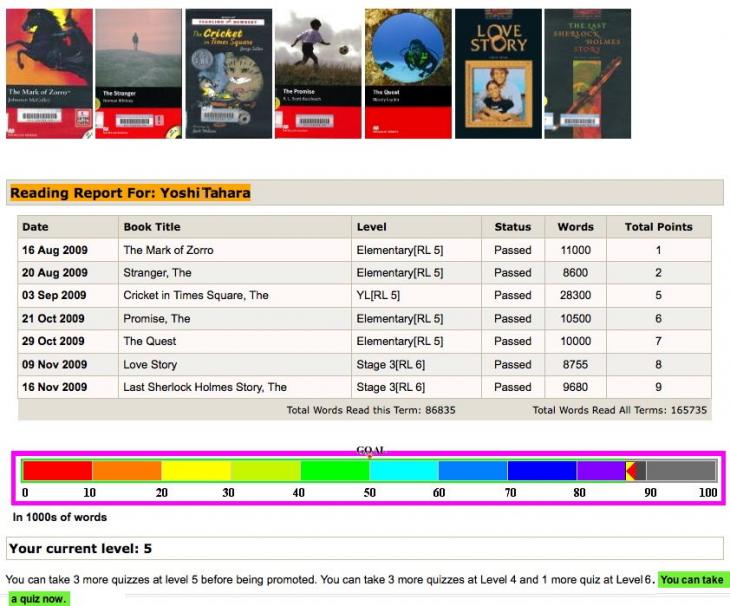

The module offers short, timed quizzes, usually with just 10 questions that take most students between 2-5 minutes to answer. The quizzes are not designed to test memory but simply to allow the students to prove that they have read the book. Quiz items vary from book to book, but generally include some multiple choice, some “who said this?”, some true/false and finally a drag and drop question where the student has to place some events in the story into the correct order. The quizzes can be taken “open book” with a time limit preventing an answer-as-you-read approach.

Features of MoodleReader

While we could have tailored MoodleReader exactly to the requirements of our particular curriculum, we realized from its inception that the tool could be shared with other schools, where ER was implemented in various forms. We therefore made virtually all of the parameters that control the module configurable by the local administrator or teacher. These include,

- The maximum length of time allowed to take a specific quiz. We have this set at 15 minutes although for non-fiction texts such as the excellent Cengage Footprints series, based on National Geographic stories, we have experimentally lowered this to 6 minutes.

- How often students can take quizzes – useful if you wish them to read regularly throughout the term. Without such a control many students might try to fulfill their reading requirement in the last few days of the term, which is not only pedagogically unsound, it is an invitation to cheat, as well.

- The difficulty level of books that each student may read which prevents students from reading material which is much too easy for them, or reading material which is much too difficult, which would slow down their reading pace and force frequent dictionary consultation.[3]

- The method of counting progress –total number books, pages or words read.

- When the module is used in a voluntary ER program, teachers often turn off the level and frequency restrictions in order for students to read whatever they want, whenever they want to. In the case of KSU, where ER is implemented as part of the curriculum, the level is controlled, with students being promoted to the next level after having read a specific number of books at their current level. [4]

Improving on the “ER by Fiat” model

As alluded to earlier, the "ER by Fiat" model has its drawbacks. In the case of KSU some instructors had never heard of the extensive reading approach prior to being asked to incorporate it in their syllabus. With most of the instructors being adjunct teachers, who are on campus for half a day twice a week, there was also no chance to provide any comprehensive information prior to the launch of the program.

The MoodleReader program does, however, allow the progress of individual classes to be tracked, which provided us with the opportunity to counsel instructors of classes with a low rate of compliance. This helped to some degree.

In the second academic year, currently underway, we have taken further steps to familiarize both students and instructors with the approach. "Class sets" of books consisting of up to 35 copies of the same title, at various reading levels have been made available for instructors to take into class for an orientation. Instructors have been advised to bring in a set that is one level lower than the level of their (streamed) class. Students read the books in class while the instructor observes their reading style, commenting on such aspects as overuse of the dictionary, using a finger or other pointer while reading line by line, etc. This experience in class is, for many, their first time to read a complete book in English, and has helped to encourage more to read. Some teachers have taken to printing out the class-by-class comparison or displaying it on the classroom projection screen in order to build a sense of inter-class competition. Finally, an evening get-together with a free meal afforded an opportunity to meet instructors face to face and give a brief presentation on the ER approach.

Student Reaction

While there will always be students who have other priorities or who hate to read, we have found that many students discover that they can actually enjoy reading in English. In the general education program, approximately 40% of the students didn't take a single quiz during the two semesters, but that means that 60% of the students did. This is additional contact with English that they would not have otherwise received. Some students soared, one reading 61 books when the goal was set at just a mere 5 per term. A full 10% of the 2500 students read 20 books or more. This student comment might be considered representative of those who enjoyed ER.

"I love extensive reading!! . . . the extensive reading books are really interesting and i can finish reading most books within 1 hour and there is a goal. I can have fun reading!"

Access to MoodleReader

From the inception of MoodleReader the staff of the KSU Department of English realized that we were developing a tool that could also be used in other schools around the world. While we created a set of quizzes to cover the books that we had available in the library, we had hoped that others would also adopt the software, and subsequently add their own quizzes to the system for those books which lacked them. While the uptake was slow at first, contributions have started to snowball. While the KSU library holds only about 500 titles, over 1050 quizzes are currently available, many created by teachers using the system elsewhere, and increasingly by publishers who are having the quizzes created in-house for the system. Oxford University Press was the first, completing Stages 4, 5 and 6 of the Bookworms series to add to the lower levels which the KSU staff had created. Other major publishers have also joined in.

The software can be downloaded from http://moodlereader.org and easily integrated into most Moodle installations. Alternately, a course can be hosted on the MoodleReader site free of charge, with students registered in individual classes within the course. The quizzes themselves can be downloaded from the central server once the module has been set in place.

Future Plans

To date, development of MoodleReader has been supported by KSU research funds as well as a grant from the Japan Ministry of Science and Education. As the number of schools using the module grows, funding will be required to provide even a minimum level of support. It is our hope that the Extensive Reading Foundation (http://erfoundation.org) might take the project under its wing once the number of users has grown convincingly large.

Caveats

Naturally, ER can only be required for all students if the reading material is equally available to all. In locations where graded readers are expensive or for other reasons inaccessible, it may be difficult to implement a program that is fair to all students. Many teachers solve the book access problem by purchasing a small number themselves, or having the students purchase one each, which are then pooled for everyone to read.

The same caveat goes for areas where universal access to computers and the Internet is problematic. The MoodleReader program, however, can be implemented on a single, shared computer if need be – without Internet access once the quizzes have been loaded.

Finally, Extensive Reading should be part of a balanced program without shunning intensive reading, which has its own set of merits. Students with certain learning styles and motivations may find the ER affords a huge jump in proficiency, while some may find it less useful.

Notes

[1] Robb (2002) and others have argued against the “orthodox” definition, which cannot easily be applied to many learner-types and learning contexts. All agree however, that ER must involve the reading of large quantities of text with a concomitant de-emphasis on full comprehension.

[2] Accelerated Reader, by Renaissance Learning, is reading quiz software that is commonly used in American schools. Problems ranged from the inability to add quizzes for books in our growing library of graded readers, to the profusion of “cheatsheets” with the answers to the questions for many books. (There were only 10 questions per book and the content never varied.)

[3] When the target goal was determined by the number of books read, students often asked for their own reading level to be lowered. (Shorter, easier books allow them to get more points.) Now that the goal is set in terms of "total words read" students are clamoring to have their level raised. (More difficult books generally have more running words.).

[4] The initial level of students is determined by the school-wide KSU placement test. Teachers are free to adjust the level for students who find their assigned level too easy or too difficult.

References

Bagster-Collins, E.W. (1933). Observations on reading. The German Quarterly, 6(4), 153-162.

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading. (1992). EPER guide to organising programmes of extensive reading. Edinburgh: Institute for Applied Language Studies, University of Edinburgh.

Extensive Reading Foundation. The Annotated Bibliography of Works on Extensive Reading in a Second Language. Available online at: http://erfoundation.org/bib/biblio2.php

Hagboldt, P. (1925). Experimenting with first year college German. The Modern Language Journal, 9 (5), 293-305.

Handschin, C. H. (1919). Individual differences and supervised study. The Modern Language Journal, 3(4), 158-173.

Hill, D. R. & Thomas, H.R. (1988). Graded Readers (Part 1). ELT Journal, 41(1), 44-52.

Lee, S. (2007). Revelations from three consecutive studies on extensive reading. RELC Journal, 38, 150-170.

Mason, B. (2006). Free voluntary reading and autonomy in second language acquisition: Improving TOEFL scores from reading alone. The International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2(1), 2-5. Retrieved October 22, 2007, from http://www.tprstories.com/ijflt/IJFLTWinter06.pdf

Renaisance Learning, Accelerated Reader (software), http://renlearn.com.

Renandya, W. A., Rajan, B. R. S., & Jacobs, G. M. (1999). Extensive reading with adult learners of English as a second language. RELC Journal, 30, 39-61.

Robb, T. (2002). Extensive reading in the Asian context -- An alternative view. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2). Available online at http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/October2002/discussion/robb.pdf

Stokes, J., Krashen, S., & Kartchner, J. (1998). Factors in the acquisition of the present subjective in Spanish: The role of reading and study. I.T.L. Review of Applied Linguistics, 121-122, 19-25.