Why Should Idioms Be Taught?

Idioms are traditionally defined as fixed multi-word phrases whose meanings cannot be predicted from the literal meanings of individual words that constitute those phrases. As such, idioms are seen as a kind of linguistic idiosyncrasy – peculiar expressions that defy both the rules of logic and the Gricean maxims of cooperative conversation. In Johnson-Laird’s (1993) words: “If natural language had been designed by a logician, idioms would not exist. They are a feature of discourse that frustrate any simple logical account of how the meanings of utterances depend on the meanings of their parts and on the syntactic relations among these parts” (p. vii).

Today, most linguists would agree that the traditional definition of idioms as ‘dead-metaphors’ fails to capture the different classes of metaphoric expressions. There is a body of evidence that suggests that the meaning of many idioms is at least partly defined by the meaning of the component words. Wasow, Sag and Nunberg (1983) claim that individual parts of idiomatic expressions have identifiable meanings from which the figurative meanings of the phrases as a whole are derived, and that the mapping between the two levels of meanings takes place in conventionalized rather than arbitrary ways. Glucksberg (2001) also observes that while some idiomatic phrases are non-compositional (e.g., spic and span), others are fully compositional, with clear semantic mapping between the constituent words and their idiomatic referents. For example, in the idiom pop the question, pop can be mapped onto ‘suddenly ask’ and ‘the question’ can be mapped onto ‘marriage proposal’. In compositional phrases, idiom constituents constrain both idiom interpretation and use. For instance, the verb kick implies a discrete, swift action making it impossible to say he kicked the bucket all week, while one could say he lay dying all week (Glucksberg, 1993).

However, despite the better understanding of idiom behaviour, there is no doubt that idiomatic expressions share some characteristics that distinguish them from other multi-word phrases. One is that although idioms may be decomposable, their overall meaning is often not immediately obvious from the meaning of their constituent elements. The other concerns the restrictions that they are subjected to in terms of lexical choices and syntactic properties such as aspect, mood or voice (Moon, 1998). While these properties affect idiom processing in both the first and the second language, there are significant differences in the cognitive load they place on native and non-native speakers.

In L1, idioms are typically acquired through exposure. This process begins in early childhood and continues well into the adulthood (Nippold & Rudzinski, 1993; Nippold & Taylor, 1995). Multiple encounters with idiomatic phrases help native speakers learn the stipulated figurative meanings, which in turn makes them perceive idioms as being more transparent (Keysar & Bly, 1995). Furthermore, experimental research has shown that native speakers have a strong intuition about idiom compositionality. Compositionality plays an important role in their perceptions of the syntactic and lexical flexibility of phrases, as well as the ease of their comprehension, with compositional phrases being processed more quickly than non-compositional ones (Gibbs, 1993; Gibbs, Nayak, & Cutting, 1989)

However, for second language learners, idioms remain a source of perplexity. One problem is that learners are not always aware of the figurative usage of the phrases. In Cieslicka’s (2006) study, learners were observed to activate the literal meanings of idioms, even when they were familiar with their idiomatic usage, and the phrases were presented in figurative contexts. Second, even if they recognize the figurative use of expressions, due to their limited linguistic proficiency and vocabulary size, learners often lack the knowledge and the skills to disambiguate the phrase meaning in the way that native speakers may do. Due to the limitations of their vocabulary knowledge in terms of both size and quality, it is more difficult for language learners to interpret figurative phrases by stretching the literal meanings of the individual words, a strategy that Grant and Bauer (2004) argue is sufficient for decoding the meaning of a large number of figurative idioms. Limited vocabulary knowledge also prevents them from recognizing the constraining effect that individual words may have on the syntactic behaviour of the phrases as a whole. Many idioms are also culturally embedded. Idioms’ meanings are not motivated only by their lexical components, but also by the specific cultural and historical context in which they originated (Boers, Demecheleer & Eyckmans, 2004). Therefore, learners are likely to experience additional difficulties in comprehension of the phrases that draw on metaphoric themes that do not exist in their culture (Boers & Demecheleer, 2001).

Learners also often lack the skills to take advantage of contextual clues, and the contexts are often not rich enough to make it possible for learners to infer the meaning of unfamiliar idioms and acquire idioms incidentally (Boers, Eyckmans & Stengers, 2007). Moreover, even if learners succeed in inferring an idiom meaning correctly, it is unlikely that the phrase will be immediately retained for subsequent use. As Lindstomberg and Boers (2008) point out, learning multi-word chunks is generally a slow process, which requires multiple encounters with the target expressions. Considering the limited contact with the target language that most learners have, only the highest frequency idioms are likely to be taken up incidentally. Incidental uptake is also likely to be difficult due to the fact that in natural communication people tend to focus on the meaning rather than on the linguistic form. Therefore, if idiom meaning is inferred correctly, and there is no communication breakdown, it is unlikely that the learners will pay attention to the exact wording of the phrase, which is crucial for correct idiom usage.

The pervasiveness of idiomatic expressions in the natural language, the intrinsic difficulties that figurative language entails, insufficient exposure, and the limited lexical proficiency of second language learners, their lack of knowledge of cultural and historical contexts, and their general bias towards literal interpretation, are all strong arguments in favour of the explicit teaching of idiomatic language. Yet, despite a significant progress that has been made in the understanding of idiom properties and behaviour, the traditional view of idioms as “dead metaphors” that can only be mastered through rote memorization still seems to dominate second language teaching practices. This assumption is also reflected in teaching materials. As far back as 1986, Irujo observed that idioms were either entirely omitted from English textbooks or, if included, were just listed in vocabulary sections of the textbook chapters, without any activities that could help learners remember their meaning or master their usage (1986a). Regrettably, thirty years later, little has changed.

While in recent years there have been some new publications devoted to idioms, such as English Idioms in Use by O’Dell and McCarthy (2010), these books seem to be intended for self-study by highly motivated language learners, or to be used as supplementary materials in the classroom. In the majority of ‘main’ EFL textbooks, idiomatic language is still marginalized. Many textbooks simply do not include any idiomatic expressions, and those that do, do not present them in any systematic way. Even reference books on vocabulary teaching do not seem to give sufficient attention to idiomatic language. For instance, in Vocabulary in Language Teaching (Schmitt, 2000) only about half a page is devoted to idioms, and the highly popular Teaching and Learning Vocabulary by Paul Nation (1990) does not include any idiom teaching activities.

Considering all the aforementioned challenges that idiom learning entails, it seems highly unlikely that L2 learners will be able to master idiomatic language by themselves. To begin with, learners are not always aware of the figurative usage of the phrases. In Cieslicka’s (2006) study, learners were observed to activate the literal meanings of idioms, even when they were familiar with their idiomatic usage, and the phrases were presented in figurative contexts. Furthermore, even if they recognize the figurative use of expressions, due to their limited linguistic proficiency and vocabulary size, second language learners often lack the skills to take advantage of contextual clues to disambiguate the phrase meaning in the way that the native speakers may do. Moreover, contexts themselves are often not rich enough to make it possible for learners to infer the meaning of unfamiliar idioms and acquire idioms incidentally (Boers, Eyckmans & Stengers, 2007).

Second, even if learners succeed in inferring an idiom meaning correctly, it is unlikely that the phrase will be immediately retained for subsequent use. As Lindstomberg and Boers (2008) point out, learning multi-word chunks is generally a slow process, which requires multiple encounters with the target expressions. Considering the limited contact with the target language that most learners have, only the highest frequency idioms are likely to be taken up incidentally. Another problem is that in natural communication, people tend to focus on the meaning rather than on the linguistic form. Therefore, if idiom meaning is inferred correctly, and there is no communication breakdown, it is unlikely that the learners will pay attention to the exact wording of the phrases, which is crucial for correct idiom usage.

The need for the explicit teaching of idioms also arises from the specific lexico-grammatical properties of these expressions. While today most linguists and language teachers would agree that the traditional definition of idioms as ‘dead-metaphors’ fails to capture the different classes of metaphoric expressions, idioms do share some characteristics that distinguish them from other multi-word phrases. One is that their overall meaning is often not immediately obvious from the meaning of their constituent elements. The other is the restrictions that they are subjected to in terms of the lexical choices and syntactic properties such as aspect, mood or voice (Moon, 1998). While these properties affect idiom processing in both the first and the second language, there are significant differences in the cognitive load they place on native and non-native speakers.

First, native speakers and language learners differ in their perceptions of idiom compositionality. Experimental research has shown that native speakers have a strong intuition about idiom compositionality. Compositionality plays an important role in their perceptions of the syntactic and lexical flexibility of phrases, as well as the ease of their comprehension, with compositional phrases being processed more quickly than non-compositional ones (Gibbs, 1993; Gibbs, Nayak, & Cutting, 1989). On the other hand, due to their limited vocabulary knowledge, learners often fail to recognize the constraining effect that individual words may have on the syntactic behaviour of the phrases as a whole.

Learners are also at a disadvantage when it comes to the perception of the semantic transparency of idiomatic phrases. Semantic transparency can be defined as “the extent to which an idiom’s meaning can be inferred from the meanings of its constituents” (Glucksberg, 2001, p.74). Some idioms are both compositional and semantically transparent. For example, in the idiom break the ice, it is easy to see how break corresponds to swift changing and how ice denotes uncomfortable social situation. Other idioms may be compositional but semantically opaque. For example, in the idiom spill the beans, it possible to map the individual words to the components of the idiom meaning, with spilling denoting unintentional revealing and beans standing for secret information. The origin of this idiom can be traced back to voting practices in ancient Greece. When there was a secret vote, white beans were placed in a jar to express support, and black ones to express opposition. Therefore, spilling the beans meant disclosing a secret. However, without knowledge of an idiom’s origin, the reason why beans denote secret is not obvious, and the phrase remains semantically opaque, even to many native speakers.

While some idioms may be semantically opaque even to native speakers, for language learners the difficulties are more complex. First, due to the limitations of their vocabulary knowledge in terms of both size and quality, it is more difficult for language learners to interpret figurative phrases by stretching the literal meanings of the individual words, the strategy that Grant and Bauer (2004) argue is sufficient for decoding the meaning of a large number of figurative idioms. Second, many idioms are culturally embedded. Idioms’ meanings are not motivated only by their lexical components, but also by the specific cultural and historical context in which they originated (Boers, Demecheleer & Eyckmans, 2004). Therefore, learners are likely to experience additional difficulties in comprehension of the phrases that draw on metaphoric themes that do not exist in their culture (Boers & Demecheleer, 2001).

In summary, the pervasiveness of idiomatic expressions in the natural language, the intrinsic difficulties that figurative language entails, insufficient exposure, the limited lexical proficiency of second language learners, their lack of knowledge of cultural and historical contexts, and their general bias towards literal interpretation are all strong arguments in favour of the explicit teaching of idiomatic language. Therefore, this paper will examine some theoretical and pedagogical issues relevant to the design and implementation of explicit idiom instruction in the L2 classroom.

Teaching and Learning L2 Idioms: From Theory to Practice

To some extent, the acquisition of idiomatic language is governed by the same cognitive processes that control other linguistic behaviour, and learning in general. General principles of long-term memory formation such as noticing, encoding, storage and retrieval underlie the learning of multi-word figurative expressions, just like they underlie the learning of the literal meanings of individual words (cf. Lindstromberg & Boers, 2008; McPherron & Randolph, 2014).

Noticing idioms in the input

In his influential paper on the role of consciousness in second language learning, Schmidt (1990) argues that noticing is one of the prerequisites for long-term information retention. Subliminal perception may be possible, but subliminal learning is not. Memory requires attention and awareness, and for input to become an intake, learners first must notice the linguistic features in the text. Based on a review of psychological studies of consciousness, Schmidt claims that noticing is influenced by factors such as learners’ expectations, frequency with which particular linguistic features appear in the input, their perceptual salience, learners’ language processing ability, and the demands that a particular task imposes on the learner.

As discussed earlier, learners tend to be biased towards the literal processing of idiomatic phrases (cf. Cieslicka, 2006). Their lack of expectations regarding the figurative usage can hinder noticing, and consequently impede the acquisition of the phrases. Therefore, it is important that teachers offer instruction that will have a priming effect and promote the noticing of idioms in the input. To begin with, the input should offer multiple encounters with the target phrase. Frequent exposure to target words is known to promote their saliency (Nation, 2001; Schmidt, 1993; Sharwood Smith, 1993). Therefore, enhanced input with multiple occurrences of the target idiom is expected to facilitate the perceptibility of figurative language.

Another issue of concern is the development of the appropriate learning tasks. There is a large body of evidence that demonstrates that information that is committed to long-term memory is information that is needed to perform the task (Ericsson & Simon, 1984). Therefore, the tasks themselves should be designed in such a way that directs learners’ attention to the figurative language usage. This may be done, for example, by placing an idiom in a question, or by asking a question that requires the correct interpretation of metaphoric meaning.

Encoding

Once the idioms have been noticed in the input, they need to be encoded into the memory system for storage and later retrieval. Encoding can be facilitated in a number of ways. Cognitive theories that concern memory which are of particular significance for vocabulary teaching and phraseology studies include the theory of conceptual metaphors (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), the dual-coding theory (Clark & Paivio, 1991; Paivio, 1971, 1990), and the levels-of-processing theory (Cermak & Craik, 1979; Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Craik & Tulving, 1975).

The theory of conceptual metaphors

In their seminal work Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) claim that many idiomatic expressions are linguistic realisations of conceptual metaphors. In cognitive linguistics, conceptual metaphor denotes a figurative comparison in which one idea (or conceptual domain) is understood in terms of another. For example, in the expression “prices are rising”, quantity is understood in terms of directionality. According to Lakoff and Johnson, conceptual metaphors underlie our thought and perception and shape our language. Linguistic choices in figurative language are not arbitrary, but a product of the language-users’ experience of their physical, social and cultural environment. Numerous examples are offered as evidence for the metaphorical nature of the human conceptual system and the semantic motivation of idiomatic expressions. For instance, idioms such as to leave a bad taste in one’s mouth, to smell fishy, to sink one’s teeth into something, food for thought, to spoon feed, on the back burner reflect the conceptual metaphor IDEAS ARE FOOD. Expressions such as to take one’s chances, the odds are against one, to have an ace up one’s sleeve, to hold all the aces, to be a toss-up, to play one’s cards right can all be seen as realizations of the conceptual metaphor LIFE IS A GAMBLING GAME. Many conceptual metaphors are grounded in human experience, and the regularity with which they reoccur in different languages has led some scientists to hypothesize that the mapping between conceptual domains may be a reflection of neural mappings in the brain (cf. Feldman & Narayanan, 2004).

The conceptual metaphor theory has brought about a major change in the understanding of figurative language. It has become clear that lexical choices in many idiomatic expressions are semantically motivated rather than arbitrary. Although people may not always have explicit awareness of conceptual metaphors, their tacit knowledge of metaphoric themes motivates both their comprehension and the production of idiomatic language (Gibbs, Bogdanovich, Sykes, & Dale, 1997). A better understanding of the semantic motivation of figurative language has opened new opportunities for more cognitively sound practices in the teaching of idioms to second language learners. Conceptual metaphors can, to some extent “justify” lexical choices in the idiomatic phrases, and, as Lakoff (1987) points out “it is easier to remember and use motivated knowledge than arbitrary knowledge” (p. 346). The conceptual metaphor framework has also made it possible to organize idiomatic language and present it to the learners in a systematic way. Memory studies have shown that retention is improved if links between individual items can be established, and new information can be related to previously acquired knowledge (cf. Baddeley, 1999). This means that introducing idioms in sets and presenting them as systematic linguistic realizations of specific conceptual metaphors can promote learning.

A number of studies provide experimental support for this hypothesis. Boers (2000) showed that organizing figurative expressions along metaphoric themes facilitates their retention. In Csábi’s (2004) experiment, learners who were introduced to conceptual metaphors had better idiom recall rates than those who only received L1 explanations of their meanings. Beréndi, Csábi and Köveces (2008) asked two groups of upper-intermediate learners to read a text with 22 English idioms, try to infer their meanings and provide their L1 translations. In the translation task, the target idioms for the experimental group were presented under their conceptual metaphors, while for the control group they were listed in the order in which they appeared in the text. After the translation task, the students were asked to complete a cloze test with the target idioms. The same test was repeated two days later and after five months. The experimental group outperformed the control group on all three tests.

Vasiljevic (2011) compared idiom acquisition under four different learning conditions: 1) idioms grouped by conceptual metaphors with their definitions and example sentences provided in L2; 2) idioms grouped by conceptual metaphors with their meanings and example sentences provided in L1; 3) unclustered idioms with definitions and example sentences provided in L2); 4) unclustered idioms with definitions and example sentences translated into learners’ L1. The results indicated a positive effect of conceptual metaphor-based instruction, especially when the concepts were introduced in the learners’ first language. In short, experimental evidence suggests that the conceptual metaphor approach can enhance the encoding of L2 idioms, making them more semantically transparent and more memorable to the learners.

Dual-coding theory

Dual-coding theory is a theory of cognition initially formulated by Alan Paivio in 1971, which holds that the human mind operates with two types of mental codes: one which controls encoding, storage and the retrieval of verbal input, and the other which processes visual information. The two levels of mental representation are functionally independent but interconnected, and therefore input that is encoded both visually and verbally is likely to be remembered and retrieved more easily than information for which there is one code only.

A large number of experimental studies have provided evidence in support of the dual-coding theory. For example, people were found to have more difficulty performing two tasks that draw on the same mental code (i.e., two verbal or two visual tasks) than a verbal and a visual task together, which was attributed to the increased pressure that code-sharing places on their cognitive resources (Thomas, 2014). Dual-coding is also believed to contribute to word memorability. Better retention rates for concrete words and their higher imageability ratings have been attributed to the fact that they have both a verbal and a sensory code (Baddeley, 1999).

The dual-coding theory was one of the leading cognitive theories of the 20th century. It sparked an enormous amount of research, and it had an immense impact on psychology, cognitive science, and education, including language teaching. Although the theory never won universal acceptance and was criticized for failing to account for aspects of human cognition other than words and images, there is overwhelming empirical support for the mnemonic effect of the dual coding of input. This prompted a new line of research that looked for ways to accommodate the principles of the dual coding theory in second language vocabulary teaching, including the teaching of idiomatic language. Some of these studies examined the effect of perceptual imagery, while others looked into the functional impact of mental imagery.

Perceptual imagery and idiom teaching: The effect of pictorial support

The mnemonic effect of visual input on the acquisition of the meaning and form of idiomatic phrases was examined in a series of studies conducted by Frank Boers and his colleagues (Boers, Lindstromberg, Littlemore, Stengers & Eyckmans, 2008; Boers, Piquer-Píriz, Stengers & Eyckman, 2009).

Boers et al. (2008) conducted three case studies in which they examined the mnemonic effectiveness of pictorial elucidation, focusing on variables such as the timing at which pictorial support is introduced, and the possible influence of learners’ cognitive styles. In the study that concerned idioms, learners were asked to guess the source domains of one hundred English idioms, select their correct definitions and complete a gap-fill exercise with a missing key word in the target phrases. The students received feedback after each stage. Illustrations depicting the literal meaning of the idioms were presented during the feedback for the first exercise after the verbal explanation of the idiom’s origins. The results suggested a positive influence of visual input although the authors warned against a possible interfering effect of pictorial support when it comes to the acquisition of the structural properties of idiomatic phrases in the case of visual learners.

In 2009, Boers and his colleagues conducted a follow-up study in which they compared the effects of idiom teaching through verbal definitions only, with the instruction where definitions were accompanied with pictorial support. Similar results were obtained. Pictorial support was found to facilitate the acquisition of idiom meanings, but had a limited effect on the retention of their linguistic form.

Szczepaniak and Lew (2011) studied the mnemonic effect of imagery in idiom dictionaries. Four treatment conditions were compared:

1. Definition of idiomatic meaning + example sentence;

2. Definition of idiomatic meaning + example + etymological note;

3. Definition of idiomatic meaning + example + picture;

4. Definition of idiomatic meaning + example + picture + etymological note.

Visual support in conditions 3 and 4 consisted of pictures which showed the literal meanings of the idiomatic expressions or one of their component words. The post-test consisted of a productive knowledge assessment task for which the students were asked to recall full idiomatic forms on the basis of one lexical component, and a paraphrase selection task which measured the learners’ knowledge of idiom meanings. The results suggested a positive effect of pictorial support on the acquisition of both idiom meanings and their linguistic forms.

Vasiljevic (2013) compared idiom acquisition when the input consisted of verbal definitions only, and when the definitions were accompanied by learner-generated illustrations of the target expressions. A combination of visual and verbal clues was found to be an effective way for helping learners remember L2 idioms, in particular their linguistic form.

In short, while there is still no conclusive evidence with regard to whether pictorial support promotes more retention of idiom meaning or retention of their linguistic form, there is little doubt that visual input can facilitate the learning process.

Mental imagery and idiom teaching: The effect of etymological elaboration

In addition to perceptual imagery, a number of studies examined the effect of mental imagery on idiom acquisition. A shared assumption of these studies was that clarification of an idiom’s origin would prompt the learners to generate mental images that could help them link the literal and figurative levels of meaning, facilitating phrase retention.

In 2001, Boers conducted a small-scale study with Dutch learners of English which specifically examined the role that mental imagery might play in idiom processing. After the learners confirmed the meanings of ten English idioms in a monolingual dictionary, the experimental group was asked to hypothesize about the idiom origin, while the control group had to think of a possible context in which the phrases could be used. The experimental group did significantly better than the control group in tests of both receptive and productive knowledge.

In 2004, Boers and his colleagues conducted another study that investigated the effect that the salience of source domains has on the acquisition of L2 idioms. The experiment consisted of two multiple-choice tasks, the first one assessing the learners’ familiarity with L2 idioms, and the second examining their ability to identify the source domains of the target phrases, For example, for the idiom ‘to show someone the ropes’, the following source-domain choices were provided: a) prison/torture; b) boats/sailing; c) games/sports. The phrases for which the source domains were correctly identified were classified as etymologically transparent to the learners. The students received brief feedback on the etymology of each idiom, but no explicit reference was made to their current figurative meanings. The post-test was designed as a gap-fill task, where the target idioms were presented in a suggestive context and the learners were asked to supply the missing keyword from each phrase. Two main findings were noted. First, the correct identification of an idiom meaning tended to coincide with the recognition of its source domain. This was interpreted as evidence that idiomatic language is at least to some extent etymologically transparent to second language learners. Second, the learners’ scores on the post-test did not indicate significant differences in the recall rates for the idioms that were etymologically transparent to the learners, and those whose origin was opaque to them. The results were taken as evidence of a positive mnemonic effect of etymological feedback. Clarification of the idiom origins was believed to have triggered the dual-coding of the target phrases regardless of whether learners were successful or not at identifying their source domains.

Vasiljevic (2014) compared idiom retention and recall rates when the instructional treatment consisted of verbal definitions only, and when input was enriched by etymological notes. The results showed that etymological feedback facilitated long-term comprehension and production of L2 idioms. In 2015, Vasiljevic conducted a follow-up study which examined the effects of perceptual imagery (pictorial support) and mental imagery (etymological feedback) on the retention of the meaning and form of L2 idioms. The results showed that etymological notes promoted the retention of idiom meaning, whilst pictures facilitated the recall of their linguistic form.

However, not all experimental data support the use of etymology in L2 idiom teaching. In the aforementioned study by Szczepaniak and Lew (2011), etymology-based instruction was found to be less effective than pictorial support. As a result, Szczepaniak and Lew argue against the use of etymological notes in idiom teaching due to concerns that information about idiom origin might distract learners’ attention from the current idiom usage. However, the authors also acknowledge that the results of the study may have been influenced by the experimental design.

In short, despite some discrepancies in findings, the currently available experimental evidence provides persuasive support for a positive effect of etymology-based instruction on the comprehension and production of idiomatic language in L2.

The levels-of-processing theory

The levels-of processing-theory, initially proposed by Craik and Lockhart in 1972, stipulates that the amount of information that is retained in long-term memory depends on the amount of cognitive effort invested at the information processing stage. Richer, more elaborate coding results in stronger memory traces and better information recall. Cognitive task demands may be one reason behind the differences in findings between the studies conducted by Boers and his colleagues (Boers 2001; Boers et al., 2004) and Szczepaniak and Lew’s (2011) study. While in Boers’ experiments the learners were expected to make hypotheses about the idiom origin, in Szczepaniak and Lew’s study they were asked to read etymological notes extracted from L2 idiom dictionaries. The reading of etymological entries does not require as much cognitive effort as etymological elaboration and, as a result, the memory traces may not have been deep enough to result in long-term information retention.

Supporting evidence for a positive mnemonic effect of deep information processing in idiom learning comes also from a study conducted by Vasiljevic (2012). The study compared the acquisition of L2 idioms when pictorial support consisted of illustrations provided by the instructor, and when the pictures were drawn by the learners themselves. Both the receptive and the productive test scores were found to be higher when the students generated their own images. One possible explanation for the results is the cognitive demands that the illustration task posed on the learners. In order to illustrate the target idioms, the learners had to direct their attention to the lexical make-up of the phrases. This is believed to have strengthened referential connections between verbal and visual representations, leading to deeper coding of the input and its better retention. Encouraging students to engage in the elaborative mental processing of figurative language should help them remember idiomatic phrases better.

Affective dimension of input encoding

In addition to cognitive variables, learners’ feelings towards a task and their motivation for completing it play an important role in the effectiveness of input encoding. Boers et al. (2004) critically reflect on the experimental design of one of their early studies concerned with the effects of etymological elaboration. The learners were asked to select the source domains of the target idioms from five options. Only when they selected the correct domain did they get feedback on the origins of the expressions. This meant that some learners had to click three or four times before they received any information about the expressions. This made the task last too long and frustrating for some learners and, as the authors pointed out, some students may have resorted to random clicking just to ‘get done with it’. McPherron and Randolph (2014) also highlight the important role that emotions play in learning. They argue that a positive classroom environment and students’ interest in the materials stimulate activity in the frontal lobes and the release of endorphins in the brain, which increases students’ attention to the input and optimizes learning. Therefore, the teacher must be careful to design the tasks that will not only promote cognitive processing of the input, but also enhance the emotional involvement of the learners.

Summary

In summary, there is substantial experimental evidence that idiom encoding can be facilitated through cognitive linguistic approaches, such as the identification of conceptual metaphors and source domains, presentation of pictorial support, and the analysis of etymological semantics. These findings offer both teachers and learners new options that go beyond the outdated method of rote memorization. However, when selecting or designing a learning task, teachers should not only consider its cognitive dimension, but also its potential affective impact on the learners.

Memory storage

After the initial input encoding, the learning outcomes will also depend on how the information is stored in memory. Knowledge in the human brain is believed to be stored in a network of hierarchically-related concepts. Each concept has a number of attributes, which are present to a different degree in individual instances of the phenomenon they denote. To access knowledge, the human memory system takes advantage of language predictability, semantic restrictions imposed by the context, and general knowledge of the world (cf. Baddeley, 1999). General world knowledge is believed to be stored in the form of schema concepts or scripts, which can be defined as “integrated packages of information that can be brought to bear on the interpretation or understanding of a given event” (Baddeley, 1999, p.154). Without corresponding conceptual schemata, the interpretation of an event becomes difficult or even impossible (Bransford & Johnson, 1972).

As discussed earlier, language knowledge is contextually acquired, and language use is believed to reflect the speaker’s conceptualization of the world. While some concepts are universal, others are historical or culture-specific. This means that in addition to linguistic knowledge, learners’ comprehension may be impeded by the lack of relevant conceptual schemata. Indeed, experimental studies of cross-cultural idiom comprehension (e.g., Boers & Demecheleer, 2001; Boers, Demecheleer, & Eyckmans, 2004; Engel, 1996, qtd. in Glucksberg, 2001, p.87) showed that learners’ have more difficulty with the interpretation of idioms that reflect metaphoric themes that are absent from their culture. Therefore, cognitive approaches to idiom teaching, such as etymological elaboration and the identification of conceptual metaphors, are expected to benefit the learner not only at the phrase-encoding stage, but also when it comes to the storage of the expressions in the mental lexicon, as they are also likely to facilitate the building of relevant cultural and historical schemata that go beyond individual expressions.

Linking of idioms to their conceptual metaphors or common source domains can help learners organise idiomatic language. Organisation is known to promote remembering (Baddeley, 1999; Bower, Clark, Lesgold, & Winzenz, 1969; De Groot, 1966), and therefore, helping learners to bring some structure into the language they learn increases the probability that phrases will be committed to memory and remain retrievable to the learners in the future.

Finally, as postulated by the dual-coding theory, visual and verbal memory codes can also facilitate information retention. Images (both perceptual and mental) can help learners to unify individual lexical components within idiomatic phrases into coherent conceptual representations, and the existence of two different levels of mental representation increases the strength of memory traces and offers alternative channels for their retrieval.

Retrieval

Stored information will be of little value to the learner if it cannot be retrieved. Retrieval is a process in which information stored in the brain is brought back to a conscious level in a response to some cue. As Baddeley (1999) points out, the amount of information that is stored in the brain is much larger than the amount of information that can be retrieved at any given time.

The ease of information retrieval depends on a number of factors that include the depth of processing, the time that has lapsed since input encoding, information difficulty, distribution of learning sessions, possible interference of subsequent input, and the frequency with which information is retrieved.

As discussed earlier, the depth of input coding affects the subsequent storage and the retrievability of information. Information that is encoded semantically, with rich and elaborate representations, is likely to be more accessible than information that is processed in a simple, superficial manner (Baddeley, 1999).

In his classic study of memory trace formation and loss, Ebbinghaus (1885) found that information loss tends to be logarithmic rather than linear – forgetting occurs quickly at first and then slows down gradually. This proved to be true for many types of learned materials. With regard to language learning, Bahrick and Phelps (1987) found that forgetting tends to be fastest in the first two years after the learning period and then levels off with little change over the next thirty years.

Another factor that contributes to the durability of memory traces is the distribution of learning. Spaced learning (i.e., learning that is distributed across a period of time) has been found to be more effective than massed practice. In other words, learning little and often is more beneficial than a couple of marathon lessons (cf. Baddeley, 1999).

The durability of memory traces has also been found to depend on the subsequent input. When new information is similar to information that is already stored in the memory, interference between memory traces is likely to occur, with some memory traces eventually being lost (Baddeley & Hitch, 1977). Interference can be both proactive and retroactive. That is old memories may interfere with the formation of new memory traces, or new memory traces may lead to the decay of older memories. An implication for language teaching is that words or phrases that could potentially cause interference should not be taught together. In a study conducted by Vasiljevic (2014), a synchronous presentation of idioms ‘bring someone to heel’ and ‘jump through the hoops’ resulted in one student coining the phrase ‘bring to the hoops.’ Whilst hoop and heel have different meanings, and at first sight may not seem to be similar, a closer observation reveals a number of formal similarities. Both items are four-letter words beginning with ‘h’, and both words have a duplicated vowel in the middle. The target phrases were also of the same length, both beginning with a verb. Considering all these similarities, above it is easy to see how the mix-up of lexical items has occurred. Teachers must pay close attention to item selection in order to reduce the potential interference effect.

Finally, the frequency with which information is selected for retrieval can also promote learning. Tulving (1967) demonstrated that multiple attempts to recall information contribute to learning. This means that tasks which require learners to retrieve the idioms that they studied earlier can help them to consolidate their knowledge. Therefore, it is crucial that teachers keep record of the phrases that learners have worked with, and offer multiple opportunities for their review.

Summary

Successful learning of idioms, like other types of learning, requires that information is noticed, encoded, stored and made available for retrieval. Teachers can facilitate memory processes by: 1) drawing learners’ attention to idiomatic expression in the input so they do not get unnoticed; 2) applying cognitive-based approaches that are likely to result in deeper coding and more durable memory traces, which should help learners to commit figurative expressions to their long-term memory; 3) offering learners extensive opportunities for idiom re-noticing and retrieval that can help them to consolidate their knowledge (cf. Lindstromberg & Boers, 2008; McPherron & Randolph, 2014).

Idiom Teaching Resources and Activities

Published materials

Currently available EFL literature includes several titles devoted to idiom teaching only. Some good self-study reference books include English Idioms in Use (intermediate and advanced) by O’Dell and McCarthy (2002; 2010). Each book consists of 60 two-page units. The first page provides information about the idiom meaning, register and usage, while the second page has exercises which allow learners to practice the target phrases. Idioms are topically organized, and the books contain the answer keys and an index, which shows in which units the idioms can be found.

Another good self-study text is The Idiom Book–1010 American English Idioms in 101 Two-page Lessons by Niergarth and Niergarth (2007). The book is written for high-intermediate and advanced students, and as the title suggests contains 101 lessons, with ten idioms covered in each lesson. Each unit is divided into four sections. Section A introduces the target idioms through informal conversations, which are also available on the CDs that accompany the book. Section B are gap-fill style exercises in the form of written messages (e-mails, journal entries, notes and memos), which focus learners’ attention on the structural properties of the idiomatic expressions. Sections C and D are designed to help learners to consolidate their knowledge of the target phrases. Section C consists of matching exercises in which students are asked to connect the target phrases with their definitions, while Section D offers paraphrase-style exercises in which the students are asked to restate a set of ten sentences using the target idioms. The answers to Sections C and D are available on the Pro Lingua website. The publisher grants the permission to teachers to copy individual lessons for classroom use.

One good resource for both self-study and classroom use is The Big Picture by King (1999). The book draws heavily on research in cognitive linguistics. The target idioms are grouped around their underlying conceptual metaphors, and accompanied by examples of usage and illustrations that depict the literal meanings of the phrases. Each chapter begins with a brief introduction of the conceptual metaphor, and the learners are invited to think how this metaphor is realized in their first language. There are a variety of spoken and written exercises that offer learners opportunities to practice comprehension and the active use of idiomatic expressions. I have found the Conversation Questions section to be particularly good for classwork. The questions contain the target idioms from the chapter, and give learners an opportunity to use idioms in a personal and realistic way.

Two texts that I believe can be particularly valuable to English teachers are Teaching Chunks of Language by Lindstomberg and Boers (2008) and Cat Got Your Tongue? by McPherron and Randolph (2014). Teaching Chunks of Language aims to bring the theoretical assumptions of the lexical approach and cognitive linguistics into the language classroom. These assumptions are explained briefly in the introductory chapter of the book. As suggested by the title, the book is concerned with the teaching of lexical chunks, and therefore the exercises are not limited to idioms only. However, a large portion of the text is devoted to the teaching of idiomatic language. Exercises are organized in three chapters. Activities in the first chapter are designed to help learners notice multi-word units in the text. The chapter that follows offers exercises that should help learners remember the phrases. The final chapter includes review activities developed to facilitate consolidation of the acquired knowledge. All materials in the book can be photocopied for classroom use, and additional worksheets for language chunk learning can be downloaded from the publisher’s website.

Cat Got Your Tongue?offers both theoretical arguments and practical guidelines for teaching idioms to second language learners. The book is divided into two parts. Part One reviews research in cognitive linguistics and brain and memory studies. Part Two examines beliefs about idiom teaching from both teachers’ and learners’ perspectives, and offers practical ideas for idiom teaching shared by teachers from around the world. The final chapter of the book gives reviews and ratings for print and online idiom teaching and learning resources.

Online resources

With the ever-growing number of EFL online resources, it has become easier for the teachers to share materials and teaching ideas, and easier for learners to engage in independent learning that matches their needs and interests. With regard to English idiom, there are a number of websites that list idiom definitions and example sentences. I have found the following sites particularly useful as they also offer some interactive practice activities and quizzes:

1. The Idiom Connection: www.idiomconnection.com

The site includes a large number of useful idioms grouped both alphabetically and lexically. For example, it is possible to search for idioms beginning with ‘a’ or for idioms where one of the key words is an animal, a body part, a clothing item, etc. Each idiom entry includes a definition and an example sentence, and at the end of each set of idioms there is multiple-choice style quiz with the answer key that allows learners to check their knowledge of the phrases.

2. English Club: www.englishclub.com/ref/idioms

The layout of this website is similar to The Idiom Connection. Idioms are grouped both alphabetically and by keyword. Definitions are short and clear, and some entries include information about the register and the dialect if the idiom is region specific. Each group of idioms is followed by a multiple-choice style quiz with an answer key. There are also eight sets of mixed quizzes that allow learners to test their knowledge of figurative expressions from the different categories.

3. The Idiom Jungle: http://www.autoenglish.org/jungle.html

This website offers a vast array of idioms grouped in three main categories: Essential Idioms, Fun Idioms and Sayings, and Varieties of English. Within each category, idioms are grouped either functionally (e.g., advice, exclamations, predictions) or topically (e.g., people, animals, food). For each idiom entry, there are brief notes on its meaning, and a phrase that expresses similar meaning or sentiment as the target expression. Learners can then proceed to the exercises, some of which are interactive and others which can be printed out.

4. Eye on Idioms: http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/interactives/idioms

Although this website offers activities for only seven idioms, it has great visuals and a simple layout that can serve as a model for teaching other expressions. Instruction for each idiom is divided in three stages. First, learners are presented with an image that is a literal representation of the target idiom, and then asked to make up complete a sentence by selecting the correct idiom from the list using the image as a hint. Second, they are asked to define the figurative meaning of the idiom. Finally, learners are invited to make their own example sentences. The tasks can be completed online and then printed for teachers to check.

The above-listed books and websites can be very useful resources for idiom learning, and teachers should make learners aware of them and encourage their use. However, the resources above are best suited for learners’ independent study outside of class. I will argue that for idiom instruction, just like for any other aspect of teaching, class time should be primarily used for tasks and activities that students cannot perform on their own. While there is nothing wrong with teachers using some of the aforementioned resources as supplementary materials during regular classes, having learners work on gap-fill exercises from the books that have answers keys at the back, or having the whole class work in a computer room, with individual students silently clicking on idiom definitions is obviously not the best use of class time.

The next section will focus on teaching activities that are best suited for classroom use, that is, activities that require peer interaction and teacher support. Some of these activities I learned from other teachers, some are adaptations of the activities from the published resources, and some are original activities that I have developed and found to work well with my students.

Classroom idiom teaching activities

Idioms in conversation questions

One effective way to help learners commit idiomatic phrases to memory is to insert idioms in discussion questions. For example, the aforementioned idiom textbook The Big Picture includes examples such as:

My girlfriend (boyfriend) thinks we should get married. Do you think I should duck the issue or confront it?

My friend says that having a baby is rough for the parent, but after the kid hits three it’s clear sailing. Do you agree?

Idioms can be grouped thematically or be on a variety of topics. Each approach has its advantages. Thematic grouping allows students to explore specific issues and learn to communicate about them in a precise and effective manner. It is particularly useful at the idiom encoding stage as many idioms that are used to talk about specific topics are also likely to share underlying metaphors. On the other hand, mixing idioms from different source domains is a good way of reviewing the phrases that learners have studied previously. It helps learners to consolidate their knowledge, and it also allows them to learn more about each other in a natural way.

Guessing idiom meaning from context

Guessing vocabulary from context is considered to be one of the most effective vocabulary learning strategies (Nation, 1990). It trains learners to pay attention to contextual clues, and the high-level of cognitive effort and learners’ involvement that the task entails increases the likelihood that the words will be remembered. Like in the case of individual words, inferring idiom meaning from context requires both rich contextual support and strategy practice. One good source of contextualized idiom input is the English Daily website (http://www.englishdaily626.com/idioms.php). The website contains a large number of idiomatic phrases embedded in a suggestive context. The target idioms are presented in short narratives and dialogues, in which the idioms are first used in context and then clarified. For example, for the idiom on the line, the following narrative is given:

Lately Tom's been more conscientious about the accuracy and quality of his work with the company. He was warned that his job was on the line because of his lack of concern for his duties. When Tom was alerted that he was in danger of losing his job, he began to take his obligations with the company more seriously.

In the original text, the idiom and its definition are coded in different colours, making it possible for learners to study the phrases by themselves. However, as there are no quizzes or other activities, the website might be more suitable for classwork. McPherron and Randolph (2014) suggest an activity in which the teacher presents the first part of the text to the students and asks them to try to infer the idiom meaning. After that the teacher shows the second part of the narrative or dialogue, so that learners can confirm the idiom meaning and correct their responses if necessary. The texts can also be used to introduce the target idioms that can then be furthered explored through other activities.

Teach your idiom (‘Eye on Idioms’ activities)

The above-described ‘Eye on Idioms’ exercise format can be easily adapted into student-generated idiom learning activities. Ten target idioms are divided into two sets of five. Students work in groups of four or five members. Each group gets one set of idioms with some information as to their meaning and usage. Based on the notes, the students are asked to make ‘Eye on Idioms’ style worksheet: an illustration, an example sentence with suggestive context in which the target idiom is gapped, and a list of response options that includes the target idiom and five distractors. They are then instructed to teach these idioms to the other group, which has to select the correct response, guess the figurative meaning of the idiom, and make an example sentence that illustrates its usage. Students generally enjoy this activity and most learning takes place during the teaching preparation stage. The teacher monitors and facilitates as needed. For higher-level students, the task can be made more challenging by presenting idioms in context, and asking the learners to infer phrase meanings before they assume the role of the teacher.

Comparing idioms in L1 and L2

Experimental research shows that, in order to decode the meanings of L2 idioms, learners consider both the literal meanings of phrase components and their similarities to figurative expressions in their native language (Abel, 2003; Bortfield, 2003; Irujo, 1986b; Pimenova, 2011). Therefore, a comparison of L1 and L2 idioms is a useful way of raising learners’ awareness about the cross-linguistic variation of figurative expressions.

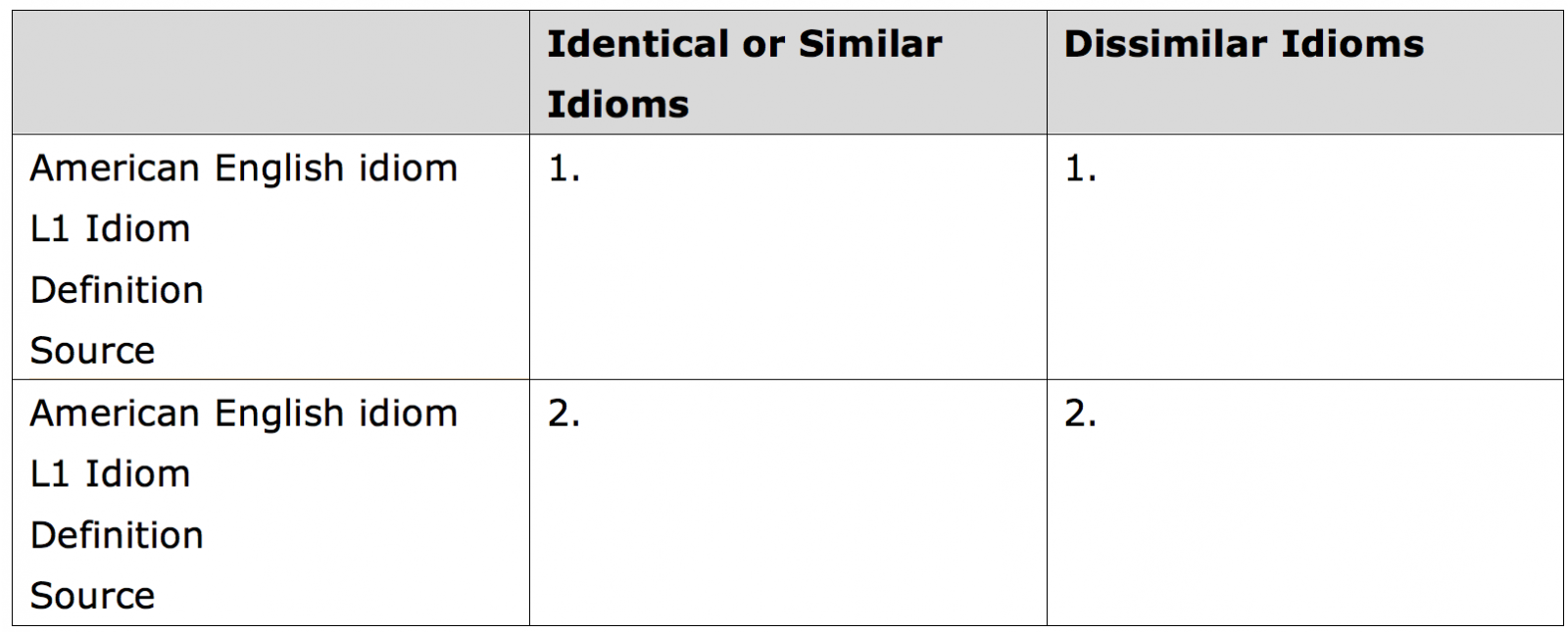

Pimenova (2014) suggests an activity where learners are asked to find two or three idioms that have the same meaning and the same structure in their native language and in American English, and two or three expressions that have the same meanings but different lexical components, or vice versa. The suggested student worksheet is simple and easy to make:

Chart 1. Student worksheet (Pimenova (2014), qtd. in McPherron & Randolph, 2014, p.162)

The students then write stories using these idioms and share them in class. This type of activity draws learners’ attention to similarities and differences between the figurative expressions in L1 and L2, and alerts them to the risks of negative inter-lingual transfer.

Usage judgment task

As discussed earlier, learners tend to process idiomatic phrases literally, and they often miss contextual clues that suggest their figurative interpretation (cf. Cieslicka, 2006). One activity that can draw learners’ attention to idiomatic meanings is the usage judgment task. Students are presented with a set of sentences in which some idioms are used figuratively and others in which phrases preserve their literal meanings. For example:

a) Poor blood circulation often gets you cold feet.

b) He said he was going to try bungee jumping, but he got cold feet when he saw how tall the tower was.

Students are asked to judge whether idioms are used literally or figuratively, and explain the contextual clues that helped them to make their decisions.

Card-game activities

I have found card game activities to be particularly effective in helping learners to notice the similarities and differences in the lexical constituents of L1 and L2 idioms. After students have learned the meanings of L2 idioms, they are invited to play a memory card game during which they have to match the corresponding phrases in L1 and L2. The game requires observation and concentration, which are known to be conducive to learning. The fact that instruction takes the form of a game also has a positive affective value, which, as discussed earlier, benefits learning. Furthermore, multiple encounters with the target phrases during the activity, and the several cycles in which the students tend to play the game, facilitate the encoding of the target phrases and, depending on the task design, can also promote their recall. Several variations can be introduced to this game.

Version 1: Matching L1 idioms in their verbal forms with L2 idioms in their verbal forms.

Card sample 1a Card sample 1b

Note: Haber gato encerradoin Spanish literally means there is (an) enclosed cat here. The expression is used in the same sense as to smell a rat, or to have something fishy going on.

The version above is the easiest version of the task, which has been found to be effective at the idiom encoding stage. At the review stage, the task can be made more challenging by omitting one of the key words or deleting letters within the phrase components. For example:

Card sample 1c Card sample 1d

This is an effective way of focusing learners’ attention on the structural properties of the idiomatic phrases. The repeated phrase recall in the course of the game should facilitate their retention.

Version 2: Matching L1 idioms in their verbal forms with the illustrations of L2 idioms.

Card sample 2a Card sample 2b[1]

This type of task strengthens the links between the meanings of L2 idioms and their lexical composition.

Version 3: Matching L1 idiom illustrations with L2 idioms in their verbal form.

Card sample 3a[2] Card sample 3b

This version of the game facilitates the encoding of the figurative meanings of L2 idioms.

Version 4: Matching L1 idiom illustrations and L2 idiom illustrations.

Card sample 4a3 Card sample 4b2

This is a harder version of the task where the learners have to recall the figurative meanings from their literal images and then do the cross-linguistic matching of the phrases. For better learning effect, students should be asked to verbalize the idioms when they turn over the cards.

As mentioned earlier, memory card games can be an extremely effective means of helping learners memorize the meaning and the form of L2 idioms. They facilitate the dual coding of the input, promote multiple encounters with the target phrases and have a positive affective value, which all result in better learning outcomes. One downside of these activities is the time that it takes to prepare the cards. For a bigger class, it may be necessary to have several sets of cards for each group of idioms. However, this problem can be partially resolved by sharing the work between the teachers, and having students make some idiom cards, a task they generally enjoy and that also has a positive effect on their learning. Once the cards are made, they can be re-used for many years, so the effort will pay off.

Dramatizing idioms

Another useful activity for reviewing the idioms that have been previously taught is by asking students to act out idiomatic expressions. The class is divided into an even number of small groups of four to five students, and the groups are then matched into opposing teams. Each group is then given a set of five idioms that they had learned before. The groups then take turns trying to convey the target idioms by using gestures and body language, and the opposing team has to guess which idiom is being acted out. Naturally, it is important that the teacher selects idioms that can be enacted easily.

‘In the frame’ (Identifying idiom source domains)

This activity, originally described by Boers and Lindstromberg (2006), draws learners’ attention to the source domains of an idiomatic expression. As discussed earlier, understanding idiom etymology enables learners to recognize the semantic motivation behind the lexical choices in figurative language, and helps them to create rich and vivid mental images. These facilitate idiom retention and recall. Boers & Lindstromberg (2006) suggest the following procedure:

1. The teacher selects the target idioms from three source domains (e.g., ‘games & sports’, ‘transport & travelling’, ‘war & aggression’). The number of phrases will vary depending on the class size, lesson length and learners’ level.

2. For each idiom the teacher prepares two cards. On the first card, the target idiom is presented in a suggestive context. For idiom ‘jump the gun’, the authors give the following example: Although we had agreed not to tell anyone about my pregnancy until we were absolutely certain about it, my husband JUMPED THE GUN and told his parents straightaway. The second card provides additional information about the idiom origin and its current figurative meaning. For the example, JUMP THE GUN, the origin is: An athlete contending in a running contest who jumps the gun sets off before the starting pistol has been fired and the figurative meaning is: If someone jumps the gun, the do something before the appropriate time.

In class, the teacher draws a diagram like the one below.

Figure 1. Idiom source domain worksheet (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2006)

Students read the information on the first card and then place the card in the domain that they believe is the source of the idiom. The overlapping parts of the diagram give students an option to relate idioms to more than one source domain. The students then justify their choices to their peers. After that, the teacher randomly hands out the second idiom card to a pair of students. They need to confirm or adjust the idiom position in the diagram, and then ask their classmates to try to figure out the figurative idiom meanings.

The activity can then be expanded by asking students to select idioms on which they have not worked before, and think of the possible context in which they could be used. Volunteers share their work in front of the class. Finally, when all the cards have been removed from the board, the teacher can orally quiz the students on their recollection of the target phrases and their meanings. An extensive list of possible target idioms

grouped by their source domains can be found at: http://www.hltmag.co.uk/jan06/mart05.htm

Chronological ordering/story making

One activity that always seems to engage learners is that of sorting idioms in a chronological order, or placing them in a story. The version that I found to work particularly well concerns idioms related to romantic relationships. Lindstromberg and Boers (2008) suggest dictating the following phrases to the students and asking them to put them in a plausible chronological order.

As a follow-up exercise, students can be asked to work in pairs or small groups, and make up a story adding details about places and characters. Students then share their stories with the rest of the class.

Conclusion

Considering the pervasiveness of idioms in everyday communication, and the difficulties that they present for the learners, it is clear that the marginal treatment that idiomatic language has received in the EFL context is unjustified and damaging to the learners. Idiomatic language can be taught and should be taught, and it is our duty as teachers to look for the means by which the learning burden of our students can be minimized and their learning experience optimized. Experimental research in cognitive linguistics and psychology has highlighted the ways in which idiom instruction can be made more effective, meaningful and enjoyable to the learner. It is hoped that the instructional techniques introduced in this paper and the review of the theories behind them will encourage teachers to devote more attention to idiomatic language, help them to make more informed methodological choices, and inspire them to further explore the ways in which idioms can be made more accessible and more memorable to language learners.

References

Abel, B. (2003). English idioms in the first and second language lexicon: A dual representation approach. Second Language Research, 19, 329-358.

Baddeley, A. D. (1999). Essentials of Human Memory. Hove: Psychology Press.

Baddeley, A.D., & Hitch, G. J. (1977). Recency re-examined. In S. Dornic (Ed.), Attention and Performance (pp. 647-667). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Bahrick, H.P. & Phelps, E. (1987). Retention of Spanish vocabulary over eight years. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 13 (3), 344-349.

Beréndi, M., Csábi S., & Köveces, Z. (2008). Using conceptual metaphors and metonymies in vocabulary teaching. In F. Boers, & S. Lindstromberg (Eds.), Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching Vocabulary and Phraseology (pp.65-99). The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.

Boers, F. (2000). Metaphor awareness and vocabulary retention. Applied Linguistics, 21 (4), 553-571.

Boers, F. (2001). Remembering figurative idioms by hypothesizing about their origins. Prospect, 16 (3), 35-43.

Boers, F. & Demecheleer, M. (2001). Measuring the impact of cross-cultural differences on learners’

comprehension of imageable idioms. ELT Journal, 55 (3), 255-262.

Boers, F., Demecheleer, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2004). Etymological elaboration as a strategy for learning idioms. In P. Bogaards & B. Laufer (Eds.), Vocabulary in a Second Language (pp. 53-78). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Boers, F., Eyckmans, J., & Stengers, H. (2007). Presenting figurative language with a touch of etymology: More than mere mnemonics? Language Teaching Research, 11 (1), 43-62.

Boers, F. & Lindstromberg, S. (2006). Means of mass memorisation of multi-word expressions, Part II: The power of images. Retrieved from Humanising Language Teaching, Year 8, Issue 1. URL: http://www.hltmag.co.uk/jan06/mart05.htm on October 24, 2015.

Boers, F., Lindstromberg, S., Littlemore, J., Stengers, H., & Eyckmans, J. (2008). Variables in the

mnemonic effectiveness of pictorial elucidation. In F. Boers & S. Lindstromberg (Eds.), Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching Vocabulary and Phraseology (pp.189-216). Berlin /New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Boers, F., Piquer-Piriz, A.M., Stengers, H., & Eyckmans, J. (2009). Does pictorial elucidation foster recollection of idioms? Language Teaching Research, 13 (4), 367-382.

Bortfield, H. (2003). Comprehending idioms cross-linguistically. Experimental Psychology, 50 (3), 217-230.

Bower, G.H., Clark, M.C., Lesgold, A.M., & Winzenz, D. (1969). Hierarchical retrieval schemes in recall of categorized words lists. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8, (3) 323-343.

Bransford, J.D. & Johnson, M.K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11 (6), 717-726.

Brenner, G. (2003). Webster's New World American Idioms Handbook. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Cermak, L. & Craik, F. (1979). Levels of Processing in Human Memory. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cieslicka, A. (2006). Literal salience in on-line processing of idiomatic expressions by second language learners. Second Language Research, 22 (2), 115-144.

Clark, J.M. & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3, (3), 233-262.

Cowie, A. P. & Mackin, R. (1975). Oxford Dictionary of Current Idiomatic English, Vol. I: Verbs with Prepositions and Particles. London: Oxford University Press.

Craik, F.I.M. & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, (6) 671-684.

Craik, F.I.M. & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104 (3), 268-294.

Csábi, S. (2004). A cognitive linguistic view of polysemy in English and its implications for teaching. In M. Achard & S. Niemer (Eds.), Cognitive Linguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Foreign Language Teaching (pp. 233-256). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

De Groot, A. D. (1966). Perception and memory versus thought: Some old ideas and recent findings. In B. Kleinmuntz (Ed.), Problem Solving, Research, Method and Theory (pp. 19-50). New York: Wiley.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. New York: Dover.

Engel, M. (1996). Loose cannons, the horse’s mouth and the bottom line: idioms and culture change. Paper presented at the XXVI International Congress of Psychology, Montreal, Canada.

Ericsson, K. & Simon, H. (1980). Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review, 87 (3) 215-251.

Feldman, J. & Narayanan, S. (2004). Embodied meaning in a neural theory of language. Brain and Language, 89 (2), 385–392.

Gibbs, R. W. (1993). Process and products in making sense of tropes. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (pp.252-276). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibbs, R. W., Bogdanovich, J.M., Sykes, J. R., & Dale, J. B. (1997). Metaphor in idiom comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 37, 141-154.

Gibbs, R.W., Nayak, N.P., & Cutting, C. (1989). How to kick the bucket and not decompose: Analyzability and idiom processing. Journal of Memory and Language, 28 (5), 576-593.

Glucksberg, S. (1993). Idiom meaning and allusional context. In C. Cacciari & P. Tabossi (Eds.), Idioms (pp. 3-26). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Glucksberg, S. (2001). Understanding Figurative Language. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grant, L. & Bauer, L. (2004). Criteria for re-defining idioms: Are we barking up the wrong tree? Applied Linguistics, 25 (1), 38-61.

Irujo, S. (1986a). A piece of cake: Learning and teaching idioms. ELT Journal, 40 (3), 236-242.

Irujo, S. (1986b). Don’t put your leg in your mouth: Transfer in the acquisition of idioms in a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 20 (2), 287-304.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1993). Foreword. In C. Cacciari & P. Tabossi (Eds.) Idioms. Processing, Structure and Interpretation (pp. vii-x). Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum.

Keysar, B. & Bly, B.M. (1995). Intuitions of the transparency of idioms: Can one keep a secret by spilling the beans? Journal of Memory and Language, 34, 89-109.

King, K. (1999). The Big Picture: Idioms as Metaphors. Boston: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lindstromberg, S. & Boers, F. (2008). Teaching Chunks of Language. Austria: Helbling Languages.

McCarthy, M. & O’Dell, F. (2002). English Idioms in Use (Intermediate). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McPherron, P. & Randolph, P. T. (2014). Cat Got Your Tongue? Recent Research and Classroom Practices for Teaching Idioms to English Learners Around the World. Maryland: TESOL Press.

Moon, R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English, A Corpus-based Approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nation, I.S.P. (1990). Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. New York: Newbury House.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Niergarth, H. & Niergarth, E. (2007). The Idiom Book: 1010 Idioms in 101 Two-page Lessons. Brattleboro, VT: ProLingua Associates.

Nippold, M. A. & Rudzinski, M. (1993). Familiarity and transparency in idiom explanation: a developmental study of children and adolescents. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36 (4), 728-737.

Nippold, M. A. & Taylor, C. L. (1995). Idiom understanding in youth: Further examination of familiarity and transparency. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38 (2) 426-433.

O’Dell, F. & McCarthy, M. (2010). English Idioms in Use (Advanced). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and Verbal Processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Paivio, A. (1990. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pimenova, N. (2011). Idiom Comprehension Strategies Used by English and Russian Language Learners in Think-aloud Study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University,

Pimenova, N. (2014). Comparing idioms in L1 and L2. In P. McPherron & P. Randolph, Cat Got your Tongue? Recent Research and Classroom Practices for Teaching Idioms to English Learners Around the World (pp. 160-162). Maryland: TESOL Press.

Schmidt, R. W. (1990). The role of consciousness in the second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11 (2), 129-158.

Schmidt, R. W. (1993). Consciousness, Learning and Interlanguage Pragmatics. Paper presented at the Meeting of the World Congress of Applied Linguistics sponsored by the International Association of Applied Linguistics (9th, Thessaloniki, Greece, April 15-21, 1990. Retrieved from URL: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED326055.pdf on October 24, 2015.

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1993). Input enhancement in instructed SLA: Theoretical bases. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15 (2),165–179.

Szczepaniak, R., & Lew, R. (2011). The role of imagery in dictionaries of idioms. Applied Linguistics, 32 (3), 323-347.

Thomas, N. J. T. (2014). Mental imagery, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (Ed.) Retrieved from URL: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/mental-imagery on October 24, 2015.

Tulving, E. (1967). The effects of presentation and recall of material in free-recall learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6 (2), 175-184.

Vasiljevic, Z. (2011). Using conceptual metaphors and L1 definitions in teaching idioms to non-native speakers. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 8 (3), 151-176.

Vasiljevic, Z. (2012). Teaching Idioms through Pictorial Elucidation. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 9 (3), 75-105.

Vasiljevic, Z. (2013). Dual coding theory and the teaching of idiomatic language. Bunkyo University, Bulletin of The Faculty of Language and Literature, 27 (1), 1-34.

Vasiljevic, Z. (2014). Effects of verbal definitions and etymological notes on comprehension and recall of L2 idioms. JELTAL, 2 (2), 92-109.

Vasiljevic, Z. (2015). Imagery and idiom teaching (Effects of the learner-generated illustrations and etymology). International Journal of Arts and Science, 8 (1), 25-42. Retrieved from URL: http://www.universitypublications.net/ijas/0801/html/E5X68.xml on October 24, 2015.

Wasow, T., Sag, I., & Nunberg, G. (1983). Idioms: An interim report. In S. Hattori & K. Inoue (Eds.), Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress of Linguistics (pp. 102-105). Tokyo: CIPL.