Introduction

Language testing is an integrated and necessary part of language programs. In Mexico, the potential market for language tests is significant. A study done by the British Council (2015) demonstrated that around 20% of Mexicans study English. However, only a handful of Mexican universities are beginning to create their own English proficiency tests. Most depend on tests created overseas by companies such as Educational Testing Service (ETS) from the US, Cambridge, Pearson, and Trinity from the UK. Several countries where English is not spoken as an official language have developed and use their own English-language testing programs in order to align test contents and scores more closely with their own framework of English education and to meet the specific needs and linguistic profiles of their English language learners. For example, Argentina has the Certificados en Lenguas Extranjeras (CLE)[1],. Mexico has Exámenes de Certificación de Lengua Inglesa (EXAVER)[2]. Taiwan has its own English proficiency exam, called The General English Proficiency Test (GEPT)[3], and South Korea has the Test of English Proficiency (TEPS)[4], Japan also has EIKEN (Jitsuyo Eigo Gino Kentei - Test in Practical English Proficiency)[5]. It is important to note that language assessment serves as the touchstone for curriculum development, instructional practice, learner advancement and achievement, and program evaluation and improvement (Norris, 2006). Fulcher & Davidson (2007) argue that tests play a fundamental role in gaining access to limited resources and opportunities. Thus, by becoming competent in language testing and creating quality systems for language assessment, local universities will be able to make tests based on their local needs and resources and make informed and important instructional decisions about them (Bachman & Palmer,1996; Carr, 2011).

To address this need for a deeper understanding of language assessment, the university has launched the Language Test Research and Development Unit (LTRD), which is responsible for designing, developing, and conducting research on various language test materials. We believe that this research is important to the EFL community because local universities and scholars would benefit from a model they can follow to create valid and reliable tests. Moreover, since this was funded by investors in Mexico to take advantage of the growing needs of assessment, it provides an example of how research and development in EFL can be beneficial to both academics and investors through the obtainment of knowledge needed to participate in emerging trends in the market.

Test Development Process

As can be seen in Figure 1 below, when the LRTD designs and develops a language test, we start by creating a design statement which includes description of the test takers and other stakeholders, intended beneficial consequences, descriptions of the decisions to be made, and the construct to be assessed (Bachman & Palmer, 2010). Once the design statement has been developed, test specifications need to be created to provide the plans for a test such as how the test items are written, how the test layout is structured, and how test takers’ responses are scored (Fulcher & Davidson, 2007). Based on a design statement and test specifications, passages are either collected or created, and items and prompts are constructed by test developers who are trained in language testing. In the next step, pilot testing needs to be conducted before it becomes operational. Once a test has been piloted, item statistics should be calculated to identify problematic items and such items need to be either revised or removed from the test. It is important to note that the whole test development process is an iterative one in which all the tasks are undertaken in a cyclical fashion. Thus, the design statement and test specifications should be continually evolving documents, and a well-built test is constantly adapted and changed to better suit the needs of stakeholders.

.jpg)

.jpg)

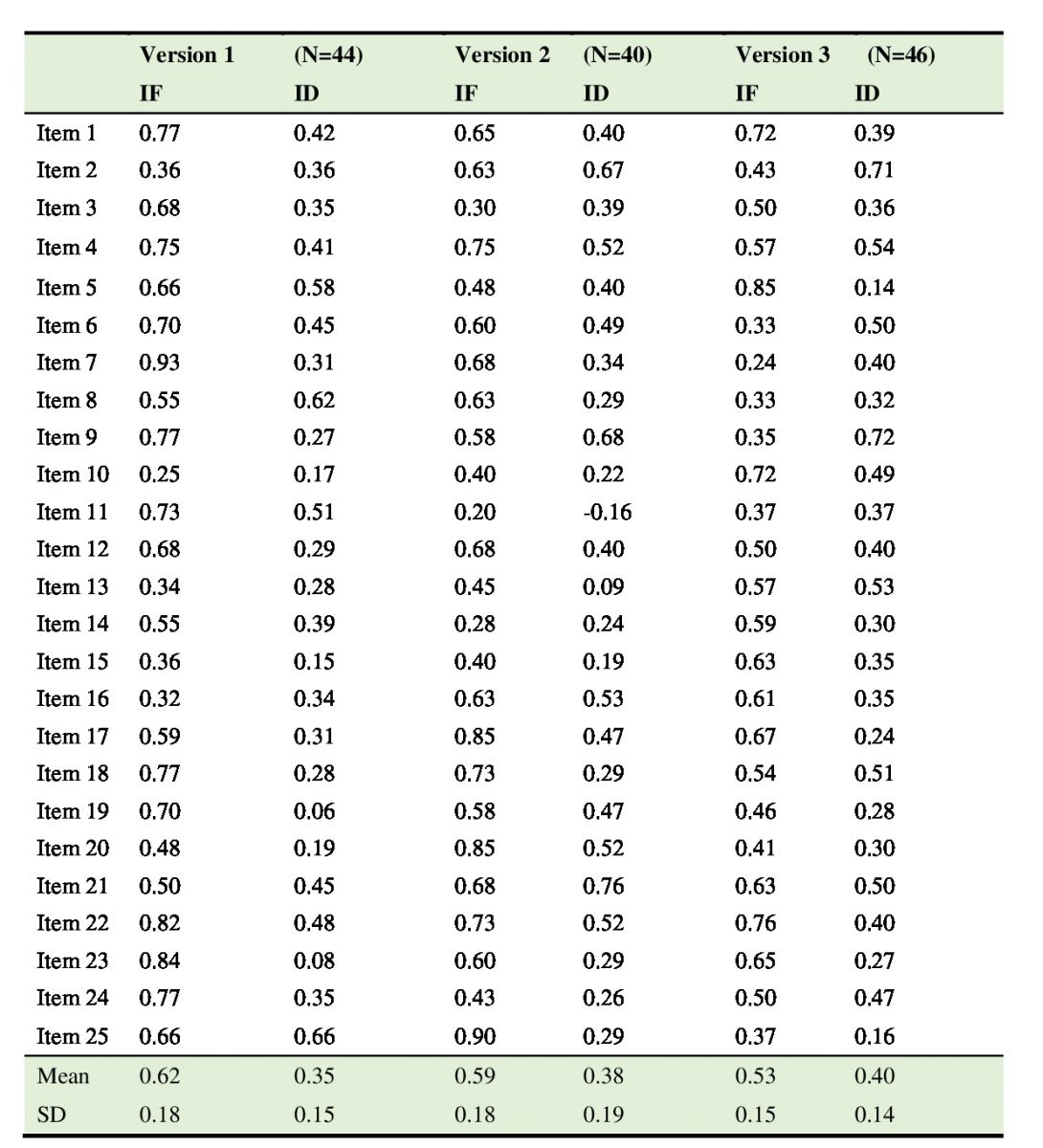

Table 1: Item Facility (IF) and Item Discrimination (ID) values of the Reading section

Table 2: Item facility (IF) and Item discrimination (ID) values of the Listening section

Item facility is a statistic used to estimate the percentage of test takers who correctly answered a given item. Since this is the percentage term, it ranges from 0 to 1. Sometimes, it is also called item difficulty. The acceptable values for item facility fall in a range between .3 and .7 in a norm-referenced testing context. Item discrimination is a statistic that indicates how well a given item separates test takers with high and low ability determined by their total test scores. It ranges from -1 to +1, and the higher item discrimination values are, the more discriminative a given item is. It can be estimated by calculating the point-biserial correlations between each item score and the total test scores. As a rule-of-thumb items with discrimination values below .19 should be revised or removed (Ebel & Frisbie, 1986). As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 above, the means of each IF and ID and most of each individual item are all within acceptable ranges.

Test format, pilot test results, and evidence of test usefulness are presented below.

Test Specifications

The EPT is designed for Mexican secondary school or college students who need to prove their level of English proficiency to satisfy one of their graduation requirements in college or a language course completion requisite, or to demonstrate their English proficiency for employment. The EPT was designed to mirror authentic language where language learners need be able to use both their receptive and productive skills for communicative situations they might undertake. To that end, the EPT assesses the four language skills including reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Test takers will receive the score report containing both percentage and standardized scores along with a graphic display of their performance in each language skill. Based on the total test scores, one of the following English proficiency certificates will be awarded to them: Pass with Distinction (CENNI level 10), Pass with Merit (CENNI level 9), Pass (CENNI level 8), and Borderline (CENNI level 7). Except for “Borderline” score, the first three certificates “Pass with Distinction”, “Pass with Merit”, and “Pass” indicate that test takers’ English proficiency is at the B1 level, but with relatively different degrees of English proficiency. This grading scheme mirrors similar ones, such as the Trinity Integrated Skills in English (ISE) 2 test, and the Cambridge Preliminary English Test (PET).

In the following section, more detailed information about each of the four languageskills being tested is provided.

EPT Reading

The reading section measures test takers’ ability to understand a range of factual and descriptive texts and passages. Particularly, they are assessed on how well they can understand the main idea, major points, important facts and details, vocabulary in context, and pronoun usage of a paragraph or text. They are also assessed on whether they can make inferences about what is implied in a passage and can synthesize information from longer, distinct texts or different parts of a text. The total time for the reading section is 40 minutes. There are 25 questions, and each of them is worth one point. The reading section accounts for 25% of the whole exam grade.

The EPT Reading section includes two tasks: a long reading and multi-text reading. In the first task, test takers read a factual, descriptive passage consisting of about 400 words and four to five paragraphs. The reading passage is followed by ten true-false questions on title matching for each paragraph and true statement selection, and by five multiple-choice questions with four choices and a single answer for assessing test takers’ basic comprehension of the text. In the second task, test takers read three short texts on the same topic about travel, money, health, fitness, foreign language learning, festivals, transportation, and music. There are five true/false/not given questions for selecting true statements to check test takers’ ability to understand key details from each text. The remaining five questions are part of a summary completion task which asks test takers to fill in the blank in the sentences, summarizing each text with a word or phrases taken from the text (Proulex, n.d.).

EPT Writing

The Writing section measures test takers’ ability to write in English in an educational context. Writing in a clear, well-organized manner is an essential academic skill required in all educational contexts. Given that academic writing usually involves source texts to which writers need to respond (Shin & Ewert, 2015), the EPT Writing section includes two writing tasks tapping into two different types of writing: integrated writing and independent writing.

For assessing test takers’ integrated writing skill, we implemented the reading-to-write section, where test takers respond to a prompt based on their readings of the four texts they have read from the previous multi-text Reading section. In this task, test takers are asked to identify and combine information from three reading passages that are relevant to the prompt in their own words and to present and support their opinions relating to points made in each reading passage. Their responses to the reading-to-write task are scored on the quality of their writing (integration, task achievement, organization, and language use) on a scale of zero to four.

The second independent writing task is extended writing with no support of source texts. Test takers are asked to produce a narrative, descriptive response to a prompt on familiar topics to them. Their essays are rated on the overall quality of their writing (task achievement, organization, and language use) on a scale of zero to four.

The total time for the Writing section is 50 minutes to complete the two writing tasks. Test takers are expected to write about 125-150 words for each task (Proulex, n. d.)

EPT Listening

The Listening section measures test takers’ ability to understand spoken English in communication contexts. The Listening section consists of three different parts. It takes 20 minutes to complete the whole section. In the first part, test takers listen to a short monologue or dialogue containing basic narrative or descriptive information, and answer the eight multiple-choice questions with three options regarding important details of the listening passages. In the second part of the Listening section, test takers listen to a longer text where a topic is discussed in depth and respond to 10 multiple-choice questions by identifying key points and details from the text. In the last part of the Listening section, test takers listen to the three-way conversation related to the topics they have heard in the second part of the Listening section, and then they respond to seven true-false questions about the content of the conversation that they have listened to ( Proulex, n. d.

EPT Speaking

The Speaking section measures test takers’ ability to speak English effectively as outlined by the CEFR for the B1 level. This section has three different parts as discussed below. The first part contains a face-to-face interview between test takers and an interviewer about personal information and familiar topics. In part 2, test takers speak on a prepared topic independently for one to two minutes. Before taking the test, test takers must select from the list of suggested topics, including favorite movies, hobbies, future plans, holidays, pets, music, and famous places, and foods. Once a test taker has finished their mini-talk, interviewers ask one or two follow-up questions on the same topic. In part 3, test takers receive a topic card which is designed to prompt discussion in pairs or a group of three. Their performance on the Speaking section is rated by two raters on a scale of zero to five by each of the following four features: Fluency, Language use, Interaction, and Pronunciation. Test takers’ final grade on the Speaking section is the average score of the two raters. Depending on the number of test takers in each pair or group participating in a speaking section, the total time for the Speaking section range from 9 to 15 minutes.(Proulex, n. d.)

Test Usefulness

According to Bachman and Palmer (1996), the qualities of language tests can be determined by the overall usefulness of the test in terms of several different but interrelated qualities including reliability, construct validity, authenticity, impact, and practicality. In this section of the report, we present evidence of these qualities that contribute to the overall usefulness of the EPT test.

Reliability

Reliability is defined as the consistency of scoring, and is estimated statistically by calculating a reliability coefficient ranging from 0 to 1 (Carr, 2011). A reliable test will show a lack of fluctuation of scores across different characteristics of the testing conditions. In a multiple-choice test, Cronbach’s alpha is used to assess the consistency of scores across items within a test. It measures the internal consistency reliability, which is the average inter-item correlation. (Brown, 2005). As a rule-of-thumb, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient below .70 is usually not considered acceptable in many testing situations. Meanwhile, it is important to note that reliability coefficients can only indicate how reliable the whole test is in percentage terms, but it does not tell us much about how accurate each individual score is (Carr, 2011). The standard error of measurement (SEM) provides us with the band of possible fluctuations of each individual score representing the test takers’ actual level of ability. In other words, SEM can be used to check how close the observed score is to the true score. For example, if a test taker obtains a score of 70 out of 100 and the SEM is given as 5 points, using one SEM would give a true score range of 70 plus or minus 5; that is, between 65 and 75 points 68% of the time if she were to take the test repeatedly. Thus, simply put, the smaller the SEM, the more accurate the test.

As stated above, Proulex Testing Language Testing and Development Unit has designed and developed three different versions of the Proulex EPT B1, and piloted each version. Table 3 below shows reliability estimates and SEM for each version of the reading and listening sections. This demonstrates that all reliability coefficients are within an acceptable range and the SEMs are quite small, ensuring that our Proulex EPT B1 test can be used as an accurate indicator of English proficiency of young Mexican English language learners.

Table 3: Reliability estimates and SEM for three versions of reading and listening sections

Note that reliability of performance tests, such as writing and speaking tests, is as important as item-based tests (e.g., true/false and multiple-choice tests). Regarding the Writing and Speaking sections, we have piloted those tests against our Proulex students to make sure that our rubrics can be reliably applied and inter-rater reliability, which is the degree of agreement in scoring between raters, can be satisfactorily achieved. Rater training guidelines for writing assessment, which can be applied to rating speaking performance, has been developed and attached to this report. The inter-rater reliability in Table 4 below shows that all reliability coefficients are within an acceptable range.

.jpg)

Table 4: Inter-rater reliability estimates

Construct validity

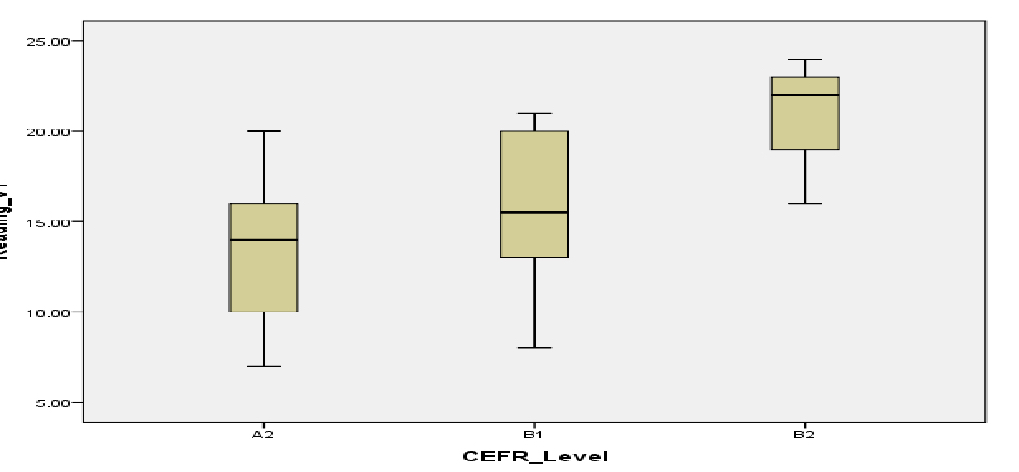

Reliability is an essential quality of test usefulness, but it alone is not a sufficient condition for usefulness. We need to demonstrate the degree to which our test scores represent the different levels of language abilities we intend to measure. Construct validity refers to the appropriateness or meaningfulness of the interpretations we make on the basis of test scores (Bachman & Palmer, 1996). Construct validity evidence is based on differential-group studies showing that the test scores differentiate between groups who are assumed to have a different degree of command of the constructs to be measured (Brown, 2005). In the pilot-testing, we identified each test taker with different degrees of English proficiency based on their course levels and teachers’ evaluations. The following six figures below show box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on each version of the reading and listening sections. The box plot is used to graphically display the distribution of test scores through their quartiles including minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. It is quite useful to compare the score distributions across different groups of test takers who took the same test. Using SPSS 20 (2011), one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was also conducted to see if there were statistically significant differences in average test scores across three groups. The differences between means were large enough to be statistically significant, and provided support for our validity argument that test scores were associated with the group comparisons, representing potentially different levels of English proficiency related to CEFR.

Figure 2: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 1 Reading Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 1 reading test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 1 Reading Test, F (2, 37) =17.14, p<.000.

Figure 3: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 2 Reading Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 2 reading test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 2 Reading Test, F (2, 25) =26.54, p<.000.

Figure 4: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 3 Reading Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 3 reading test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 3 Reading Test, F (2, 20) =13.45, p<.000.

Figure 5: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 1 Listening Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 1 listening test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 1 Listening Test, F (2, 41) = 40.47, p<.000.

Figure 6: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 2 Listening Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 2 listening test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 2 Listening Test, F (2, 37) = 49.25, p<.000.

Figure 7: Box plots for groups representing each expected CEFR levels on Version 3 Listening Test Scores

We compared the mean of version 3 listening test scores of three different groups who are assumed to represent three CEFR levels, A2, B1, and B2, and a statistically significant difference was found among the three expected levels of CEFR on Version 3 Listening Test, F (2, 43) = 63.08, p<.000.

Authenticity

Authenticity is another important aspect of test usefulness. It refers to degree to which test tasks resemble target language use tasks (Carr, 2011). Authentic language tests can allow us to make a generalization of test scores beyond the language test itself. Our EPT B1 can be said to achieve authenticity to some degree in that this test reflects real life language tasks students are expected to encounter. For example, reading passages used in the Reading section are based on authentic sources and deal with familiar, interesting topics for test takers such as travel, money, health and fitness, music, foreign language learning, etc. More importantly, we implemented an integrated reading-to-write section to more closely capture actual language use in the educational contexts where students often analyze and synthesize information found in the source texts into their own writings. In the Speaking section, we included a variety of tasks and conversation modes: monologue and dialogue including both the face-to-face interview and pair or group work formats. It is also important to note that all topics, text types, and question types are selected to match the CEFR B1 level descriptors.

Impact

Impact, or washback, refers to the influence of testing on language teaching and learning practices. We are not able to collect evidence of positive impact of our test because it has not been implemented and used yet. However, we expect beneficial influence of our test on the English instructional practices in Mexico because we incorporated integrated performance tasks which are more relevant to language uses and demands in real-life tasks (Messik, 1996).

Practicality

Practicality is another important test quality of test usefulness that refers to the degree that the resources that will be required to develop an operational test do not exceed the available resources (Bachman & Palmer, 1996, p. 36). In the case of the EPT, practicality has increased as knowledge in language assessment and project management has. Members of the LTRD have received continuous training in assessment which has led to less dependence on expensive foreign consultants. Moreover, quality management theory is used to reduce waste, increase efficiency and resolve problems (White, 1998). Thus, exam development is becoming more practical as the LTRD obtains more knowledge in assessment.

Conclusion

This paper has provided a detailed summary of the development and validation of the EPT. It has documented both the development and validation process, including the implementation of usefulness and how it links reliability, validity, authenticity, impact, and practicality. The results suggest that this test is useful and operational.

However, it is important to mention the limitations to this study for educators who intend to pursue the development and validation of tests. The sample size was rather small, and more research is needed to come up with conclusive findings in usefulness. Moreover, the fact that the reliability is below .8 in the listening test in all versions, and the medians between A2 students and B1 students measured by ANOVA in Reading V1 are similar, represent an opportunity to improve the reliability and validity. This can be done by either applying the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula and increasing the length of the test based on the result (Carr, 2011. p. 305) or by reviewing and editing the items we currently have in the listening test.

Of course, we can only reach a certain amount of certainty and not an absolute truth. For as Rorty (1999) points out “The trouble with aiming at truth is that you would not know when you have reached it, even if you had in fact reached it. But you can aim at ever more justification, the assuagement of ever more doubt” (p. 82). Hence, this study attempts to provide the evidence needed to give assurance to our claim of usefulness. Mill (1859) illustrates this when he argued, “There is no such thing as absolute certainty, but there is assurance for the purposes of human life” (p.24). Although we are not able to validate with complete certainty, we have provided a sound argument which is backed by evidence and will stand up to criticism (Toulmin, 2003, p. 8). The development of this test should help in obtaining knowledge that would allow a Mexican university to have more control of their evaluation and be able to better interpret its test results. This in turn could lead to the identification of problems in language programs and solutions, offered locally.

References

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. (2010). Language assessment in practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Brown, J. D. (2005). Testing in language programs: A comprehensive guide to English language assessment. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

The British Council (2015). English in Mexico 2015. Retrieved from https://britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/latin-america-research/English%20in%20Mexico.pdf

Carr, N. T. (2011). Designing and analyzing language tests. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ebel, R. L., & Frisbie, D. A. (1986). Essentials of educational measurement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Fulcher, G., & Davidson, F. (2007). Language testing and assessment: An advanced resource book New York, NY: Routledge.

Messik, S. (1996), Validity and washback in language testing. ETS Research Report Series, 1, i-18. Princeton, NJ: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.1996.tb01695.x

Mill, J. S. (1859), On Liberty. In J. Gray (Ed.) John Stuart Mill’s on liberty and other essays. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Norris, J. M. (2006). The why (and how) of student learning outcomes assessment in college FL education. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4). 576-583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00466_2.x

Proulex (), EPT b1 manual, Retrieved from http://www.ept.proulex.com/doc/ST_sample.pdf

Rorty, R. (1999), Philosophy and social hope. London, UK: Penguin.

Shin, S.-Y., & Ewert, D. (2015). What accounts for integrated reading-to-write task scores? Language Testing, 32(2), 259-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214560257

SPSS Inc (2011). PASW statistics for Windows: Version 20. Chicago,, IL: SPSS Inc.

Toulmin, S. (2003), The Uses of argument (2nd ed.) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

White, R. (1998), “What is quality in English language teacher education?”, ELT Journal, 52(2). 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/52.2.133