The Sorry Report

The Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (PNIEB, or NEPBE in English) was launched in 2009 by the Mexican Ministry of Education (SEP) and introduced English in the primary grades throughout the country. The ambitious program represented the largest expansion of English language instruction in the country’s history. It replaced the previous state programs carried out in 21 states, and by the Ministry’s own estimates will entail the hiring of about 98,000 new English teachers to fully implement the program in grades K-6 with 791,000 classes. With the integration of English in the secundaria (middle school grades 7-9) into the PNIEB in 2012, and the extension of compulsory education through high school, Mexico has become the first country in Latin America to include English throughout all thirteen years of the K-12 public school curriculum.

Now, five years after the program was launched, the group Mexicanos Primero has released a report called Sorry: El Aprendizaje del Inglés en México [Sorry: Learning English in Mexico] which heavily criticizes the PNIEB (O’Donoghue & Calderón Martín del Campo, 2015, with several other contributors, heretofore “the authors”) which presents the results of study of English in Mexico. As many language education policy scholars have pointed out, an important component of curriculum development is on-going program evaluation (Nation & Macalister, 2010), and this is certainly true of the PNIEB. Other recent studies have evaluated many aspects of the PNIEB (see for example the 2013 Special Issue of the MEXTESOL Journal including 12 studies of different aspects of the program, Sayer & Ramírez Romero, 2013); however the Sorry study is notable because of the widespread attention it received, including national press coverage in newspapers and on television. They state their findings dramatically: “La educación en México: Reprobado en inglés” [Education in Mexico: Failed in English].

So, what are we to make of the report? What does it tell us about the successes and failures of the first five years of the program? In what follows, I will respond to the Sorry report, and in particular its smoke-and-mirrors approach to critiquing the program. Then I will reflect on the current state of the national English program PNIEB.

The report itself is a masterpiece of graphic design. The arguments are beautifully laid out and the data and findings are clearly presented so as to be understood by the general public. But the project the report is based on is seriously flawed for three main reasons. First, it does not measure what it purports to measure: the results of the PNIEB program. Secondly, the project misleads the reader because it presents pseudo-research to back up its assertions. Instead of using empirical research to reach an objective finding, they have taken an a priori position and then fit their data to support it. Thirdly, they have grossly mischaracterized the nature of second language proficiency by using an assessment instrument that completely distorts the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR, Council of Europe, 2001) standards on which they claim the instrument is based.

If the Sorry report were merely a poor piece of research – bad design, lack of objectivity, and a flawed instrument – we could discount it, and in fact it might have some value as a tool to show students and novice educational researchers some of the difficulties and potential pitfalls of conducting research. However, the report is much more insidious, because it is a wolf in sheep’s clothing: it is political propaganda dressed up as educational research. For those of us who were surprised how much exposure and attention the report got – even two weeks before the full report itself was published in February 2015 – including national television interviews, the connection becomes clear when one realizes that the president of the Mexicanos Primero organization, Claudio X. González Guajardo, is an ex-board member of Televisa, and that the foundation is funded by Televisa. In essence, the report was paid for by Televisa in order to make the PNIEB look bad. Amongst its other politically-motivated projects, Mexicanos Primeros also produced the documentary De Panzazo, a strong critique of public schools and teachers (much in the same vein as the U.S. educational documentary Waiting for Superman). In the case of the Sorry report, they have used smoke and mirrors to mask their political intentions as if it were educational research.

The fundamental and obvious flaw in the design of the study is that they evaluated high school students in 2013. They state that they evaluated “4,727 egresados de Secundarias públicas que actualmente se encuentran cursando el nivel medio superior” [4,727 graduates of public middle/lower secondary schools who are currently studying high/secondary school] (p. 97). Since the students were in high school, between 16-18 years old when they were tested, none of the students could have possibly studied in the PNIEB, which started in 2009, much less have actually passed through all the levels starting from kindergarten up to sixth grade of primary school. Therefore, to evaluate teenagers and stretch the results to make claims about the PNIEB is cynical. In assessment, this is called problem of construct validity: the test did not actually measure what it purported to. Claims made based on an instrument or test which lacks construct validity are invalid.

I should be clear that I think critique is important, and anyone should be free to make any statement, good or bad, about an important educational policy and program such as the PNIEB. In fact, as citizens, we should be actively involved in debating all public policy, and most especially education policy that directly affects children. However, making a commentary (as I am doing so here) to express an opinion, and having the audience understand that you are expressing your opinion about the policy, is markedly different than using fake social science research to dress up a political agenda and try to score political points. The latter is, quite frankly, shameful. It is also unfortunate because despite its flaws the report has some important things to say about language education in Mexico.

My purpose in this commentary is to critique the shortcomings of the report, and highlight what I think are the contributions it makes to the discussion about how best to organize a national English program for Mexico’s public schools. I am approaching this topic from the perspective of someone who has done research on the PNIEB (as an independent researcher, and also a researcher for the national SEP and for several state administrations), and as someone who is heavily invested in the success of English language teaching in public schools.

The Difference between Empirical Research and Propaganda

There are many ways to do research, and for many purposes. Research can differ in terms of its methods, quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and even its epistemological orientation, or how the researcher understands the relationship between her work and the truth she is trying to find. But the key assumption in research is that there is an unknown out there that, through careful, systemic work of gathering and analyzing evidence, the researcher can understand and explain something about the world a little better (Creswell, 2013). This is just as true for the cancer researcher working with stem cells in a laboratory as it is for an anthropologist working in a remote village as it is for a teacher doing action research in her own classroom. So, in order to be able to look at the data collected honestly and without prejudicing the findings, the researcher must collect and analyze them as objectively as possible. Many researchers, especially in the qualitative tradition, would argue that true objectivity is impossible; therefore, it becomes all the more important to recognize and acknowledge our own biases in the research, and to strive to be more objective by reflecting on how those biases are influencing the research.

This is not to say that subjectivity has no role in research. Subjectivity comes from our own motivation for doing the research: we hope that the cancer researcher is passionate about her work to fight cancer, just as we hope that the teacher doing research in her classroom is motivated by her desire to improve the learning for her students. But subjectivity, while it motivates our work, should not influence the results of the study: the cancer researcher has to be honest about which treatments are most effective just as the teacher must analyze which method works best based on the findings, not on the researcher’s preconceived notions about what the researcher thought she would find.

When subjectivity accidentally skews the research, it becomes bad research. And when someone purposefully uses research to make a political point, it stops being research and becomes propaganda. This is what, I think, has happened with the Sorry report.

Selling Ideas

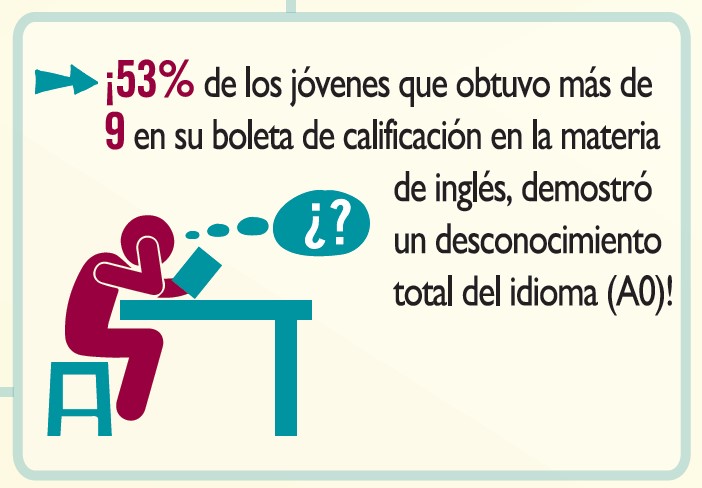

Several weeks before the full report was released, the results of the Sorry study were reported by the media. A synopsis of the report was available as a four-page summary, with the information presented in infographic form. Infographics are visually appealing, combining graphic arts and marketing techniques, and therefore become a powerful tool for presenting complex research data in a way that makes sense to a general audience. For example, the information presented on pages 76-77 of the report is an excellent summary of the current numbers of students and schools with English. However, infographics also have the power to become misinfographics: distorting information by using something that sounds scientific to convince the audience that “it must be true,” as in Figure 1:

Figure 1. An infographic from the Sorry report.

For example, research in psychology shows that we are more likely to believe a statement if it includes a statistic with a precise number (Strack & Mussweiler,1997). In Figure 1, the claim that “53% of students” becomes more scientific-sounding than “half the students” and hence more believable.

To illustrate, I designed an infographic I made in five minutes from the site https://venngage.com.

.jpg)

Figure 2. An invented “misinfographic”.

Looks good, right? Although I have no graphic design skills and, in fact, no real data, I can create a compelling statement. It is compelling, because it is plausible, and it becomes convincing because I am presenting it as if I had valid data to back up my claim (which I do not; to be clear Figure 2 is completely invented “misinfographic” created to make a point).

So, although the report does have some points of merit that I will discuss below, it seems to be intentionally misleading and the value of the project is reduced to politically-motivated sound bites presented through flashy infographics. The report therefore uses the PNIEB to make a thinly veiled attack on teachers and the public education system in general.

The Nature of Assessing Language Proficiency

In order to obtain results about Mexican students’ knowledge of English, Mexicanos Primeros created their own standardized instrument. Any test designer will admit that creating a new instrument, especially to evaluate something as complex as global language proficiency, is a difficult and time-consuming undertaking involving psychometrics (the field of study to measure something in someone’s brain, such as language competence), piloting and revising test items, and validating the test results. Since the goal was measure students against the Common European Framework of Reference language proficiency scale, they may have done well to use any of a number of tests that already exist and have been accurately scaled against the CEFR.

Nevertheless, the Sorry report explains that test they created is called the “Test of Use and Compression of English for Students who Completed Middle School” (Examen del Uso y Compresión del Idioma Inglés para Egresados de Secundaria, or EUCIS). Here “compression” presumably means “comprehension” unless this is some new language facility they have discovered that has been previously unknown to linguists. Also, we will leave aside the fact that they actually tested high school, not middle school students. Let’s look at how they describe the instrument and the examples they provided of the test questions.

The authors explain that “el propósito del EUCIS es identificar el nivel de dominio del inglés en situaciones comunicativas básicas con el uso de prácticas sociales del lenguaje en un contexto cotidiano y de supervivencia, lo cual está en línea con lo establecido en el programa de Educación Básica.”[The purpose of the EUCIS is to identify the level of English proficiency in basic communicative situations with the use of social practices of language in everyday contexts and for survival, which is aligned with the objectives established in the program of Basic Education.] (p. 96). They state that they tested five different abilities: listening comprehension, reading comprehension, vocabulary, grammar, and multimodal.

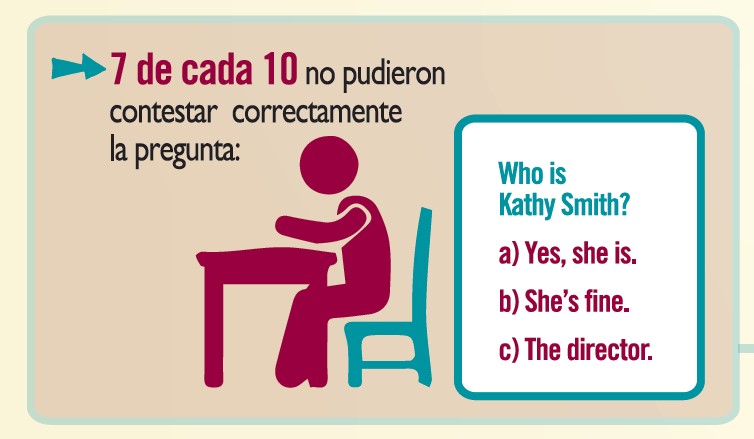

Figure 3 shows an example of a question from the test provided in the report, again in infographic form.

Figure 3. An example of a test item from the EUCIS.

It is unclear what linguistic ability is being tested, but it is presumably reading comprehension. We might say that for Figure 3 the best answer would be:(d) I have no idea who Kathy Smith because you haven’t given me any context to interpret what you are asking me. Despite their claim that the EUCIS tests communicatively in everyday social situations, from the examples provided it is difficult to see how there is any context within the test that constitute “social situations” that would be recognizable to students taking the test.

The following question is given as an example of a “multimodal” item at the B1 level (p. 92).

Where’s Rosa? I haven’t seen her lately.

a. She’s always late.

b. She’s visiting her family in Mexico.

c. She will be visited by her family

Apparently, the expected response is (b). However, it also seems that (c) and maybe to some extent (a) could be appropriate. For example, if the speaker was explaining “She will be visited by her family, and so she has had to go back to her village to help her mother prepare for the visit and that’s why you haven’t seen her this week.” Again, with the items stripped from the social context, almost any of the answers could potentially be plausible, not just the one that the test designer has arbitrarily chosen as the “correct” response. This type of problem undermines the authors’ claim that students’ failure on the test therefore demonstrates their lack of communicative abilities: “No pueden poner en práctica [su conocimiento del inglés] ni siquiera en una comunicación sencilla” [They cannot even put into practice their [knowledge of English] in simple communication] (p. 93-94). In actual communicative situations, of course, interlocutors will have a lot of information from the context with which to interpret the speaker’s meaning, as well as the chance for negotiation of meaning, and information gleaned from intonation and paralinguistic clues. Hence, in the sample items provided the authors are not measuring language in communication, they are measuring decontextualized test language. In the field of language assessment, this problem is called content validity, since the items do not accurately measure what they are trying to measure (i.e., communicative language use).

Another problem with the test design is the choice of “skills” that are being evaluated. Language proficiency tests usually test the four skills: reading, writing, listening and speaking, with other related sub-skills included with each. So pronunciation is a sub-skill of speaking, spelling is a sub-skill of writing, and knowledge of vocabulary and grammar are usually included across the board. In the EUCIS, there is no measurement of productive skills, speaking and writing, despite the fact that the authors claim to measure “use and comprehension” of the target language (p. 91). Additionally, grammar is tested separately, despite the fact that the curriculum has been oriented since 1994 towards a communicative approach, and places even less emphasis on explicit knowledge of grammatical structures in the sociocultural approach of the PNIEB. Therefore, test results may also partially be an artifact of a mismatch between the L2 elements the test designers designed to include (and exclude) and the skills emphasized in the pedagogical approach of the curriculum. Again, this is an issue of construct validity. Without evaluating productive skills, it is difficult to see how the test could really measure global proficiency according to the CEFR scale as the authors claim.

Finally, the test purports to measure the “multimodal skill” (p. 91). Multimodality usually refers to the combination of one modality with another: for example, a web page that combines written text with visuals. On the EUCIS instrument, it’s unclear what multimodal means. The above item about Rosa is given as an example of a multimodal question, but it does seem not to combine any other modality, and in fact seems to be another way of testing grammar (i.e., does the student recognize the meaning of the present perfect form “have not seen”?).

So, despite the stated purpose of evaluating students’ “use and comprehension” through “communicative situations” and “social practices,” instead the instrument seems to be oriented heavily towards decontextualized grammatical knowledge, and suffers from several types of validity problems which call into question the general conclusions the authors make about students’ language proficiency. Furthermore, the authors use the test results to argue that “las políticas y las prácticas que presentamos apuestan al aprendizaje de otro idioma como base de un desarrollo integral en el que la comunicación, el diálogo intercultural y el acceso a la información juegan un papel fundamental en el ejercicio del derecho a aprender.”[The policies and practices that we present envision the learning of another language as the basis of an integral development in which communication, intercultural dialogue, and the access to information play a fundamental role in the right to learn.] (p. 100). I agree wholeheartedly with this altruistic sentiment, but I cannot see where the EUCIS instrument has even a remote connection to telling us what students know about intercultural dialogue or accessing information. Later, they conclude: “Debemos de fomentar una forma de enseñanza que propicie el aprendizaje de otras lenguas como medio para llegar a una comprensión más completa de otras culturas así como de la nuestra, que no se limite a simples ejercicios lingüísticos, sino que propicie la reflexión sobre otros modos de vida, otras perspectivas y otras costumbres.” [We should promote a teaching method that approaches the learning of other languages as a means to better understand other cultures as well as our own, that is not limited to simple linguistic exercises, and that foments reflection about other ways of living, perspectives, and customs.] (p. 107). Again, this beautifully articulated statement is completely contradicted by the instrument itself, which focuses exclusively on evaluating isolated linguistic pieces.

The Value of the Sorry Report

Looking at the full report, the authors actually do have some valid points about access and problems with the program. In particular, the study raises important issues about the equity of access to quality English classes for children at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, as in Section 2.4 “El inglés y la oportunidad económica” by contributor Pablo Velázquez. Velázquez states that:

En una encuesta de percepción en México llevada a cabo en 2008, sólo 23% de los encuestados señaló hablar o entender el inglés (CIDAC, 2008). Sin embargo, este promedio esconde la disparidad entre la población con altos niveles de ingreso versus la población con un ingreso más bajo. Mientras 60% de la población con un ingreso mensual mayor a 10,000 pesos señaló hablar o entender inglés, sólo 11% de la población con ingresos menores de 1,600 pesos manifestó la misma condición. (p. 46)

[In one survey carried out in Mexico in 2008, only 23% of the respondents indicated that they could speak or understand English (CIDAC, 2008). However, this percentage obscures the disparity between people at higher and lower income levels. Although 60% of the population who earn more than MX$10,000 pesos per month claimed to speak or understand English, only 11% of those who earn less than MX$1,600 said the same.]

This is a finding worth highlighting, especially given the common argument that by introducing English in public schools at the primary level – historically only available to children in private schools – we can ameliorate socioeconomic differences. The authors are right to question whether the English program really can contribute to greater social equality (Sayer, 2015). The report also includes a brief but significant consideration of the indigenous education system and efforts to maintain Mexico’s indigenous language and cultures, and implicitly recognizes that the discourse of education policy about the national English program needs to engage with the larger social context in Mexico, and especially needs to consider how it affects the most marginalized and vulnerable children in the public schools (see pp. 78-80).

Clearly, the most important part of the document is David Calderón’s Chapter 3 on language policy (“La política educativa actual del inglés en México”). The author is evidently quite familiar with the inner workings of politics within the SEP, and includes some excellent insights about the political processes that motivated decisions about the implementation of the PNIEB. For example, he cites the Plan de Estudios from 1926 when English was first introduced in the national curriculum, and explains that English has been included continuously since 1941, for 74 years uninterrupted (p. 59). He traces its development, and includes mention of the earlier efforts to incorporate English into primary grades 5 and 6 through the Enciclomedia program. He also rightly acknowledges that although private schools have often used English and the “bilingual” label to market themselves, with few exception private education has not done a particularly good job of developing solid EFL programs. Calderon also recognizes that for many parents who cannot afford private schools but still want their children to learn English, they often resorted to paying for extracurricular or particular classes for their children. He considers then, within the political context in Mexico that affects education policy decisions, how the PNIEB program was developed and launched.

Finally, in Chapter 3 Calderón discusses the quality of English teachers and teaching. The “numeralia” section based on the School Census reports that as of 2014-15 there were 50,274 English teachers: 4,738 at pre-school, 13,399 in primary, 32,746 in secondary, and 47 in special education (p. 77). Thereport heavily criticizes the level of English of secundaria teachers, and Calderón recognizes that in order for the PNIEB to be successful the progression of English from the primary to secondary grades needs to be well articulated. However, he responds to a critique from Rodríguez (2014, cited on p. 73) that the PNIEB should have been initiated only after a sufficient number of teachers have been trained. He suggests, probably correctly, that given the political climate in Mexico if they had waited to begin the program until everything was in place and ready and all the teachers were prepared, the PNIEB would never have been started. As one administrator in Estado de México told me, given the enormous number of students and shortage of qualified teachers: “We don’t have enough English teachers to cover all our groups, and in thirty years we won’t have enough English teachers…” (personal communication, March 2015).

The crux of Calderón’s argument seems to be that the PNIEB is getting co-opted by political interests and so decision-making – particularly about the allocation of funding – is being made that does not reflect good education policy. That is, he insists that the PNIEB as an important educational policy for Mexico in the early 21st century, should be part of public policy (política pública) and not become political policy (política-política). He maintains that: “Lo que fue concebido como política nacional y currículum obligatorio para todo el país, pensado para favorecer igualdad de oportunidades y por ello con un perfil de egresado […] queda ahora al arbitrio de los funcionarios estatales” [The program which was conceived as a national policy and obligatory curriculum for the whole country, aimed at providing greater equality of opportunities for students going through the program […] is now at the whim of the state administrators] (p. 72). This is a well-reasoned argument, and Chapter 3 could well stand on its own merits as a language policy analysis without having to resort to basing his position on a flawed research study which undermines rather than supports his position.

The remainder of the report offers some suggestions. These are fine ideas (discounting factual errors such as the claim on p. 112 that English is the official language of the United States; it is not, and the U.S. has no official language, for reference see Wright, 2010), but most are rather too general to be very helpful, such as “Good Practice 6: Incorporate technology” (p. 106) or “Good Practice 7: Effective pedagogical strategies” (p. 107). Undoubtedly, PNIEB teachers can and will continue to receive training and to improve their teaching. What is lacking in the report are specific structural changes that need to be made to the program. In order to invest in the long-term quality of the teachers and the program, the administrative aspects of the program need to be organized in such a way to support teachers and allow them to develop professionally. While I agree with Calderón that the decision-making should not be politicized, the reality of it is that these administrative and structural changes must be made within the current political reality of public education in Mexico. Specifically, I would offer my own list of concrete suggestions for the PNIEB:

- Wage payments need to be reliable. Most of the PNIEB teachers work on “honorario” (non-tenured) contracts, and many have experienced problems being paid on time for the work they do. In several states, paychecks have been delayed for months, and create severe economic hardships and stress on the teachers. The fiscal organization of the program must be resolved so teachers who sign a contract and teach their classes have at minimum the security of knowing when and for how much their paycheck will be received.

- Equity of labor conditions. Although it is a federal program, the PNIEB is administered quite differently in each state, and as a result there are great disparities in wages, benefits, and job stability. The administrators should ensure that PNIEB teachers have a guarantee of basic and fair working conditions that is equitable across states.

- Creation of specialist degree programs. There are very few language teacher training programs which have a specialty in working with children in public schools. The Normal Schools still only offer a licenciatura (undergraduate degree) in English teaching at the secondary level, and most university programs focus on the private schools or working with adults. Programs to prepare pre-service teachers for the PNIEB, to meet the specific demands of working in public schools, need to be created.

- Qualified teachers should be given equal opportunities. In many states, qualified individuals with degrees from the autonomous universities have difficulty getting PNIEB positions because they are not graduates of the Normales. Even though they often have excellent English skills and a degree in English language teaching, many states specify that only people with certain degrees (and the name of the degree must match exactly what is on the official list) can receive a commission to teach in public schools. This creates a barrier which harms the quality of English teaching because it restricts opportunities for some of the most-skilled English teachers.

- Create innovative programs for people with strong English skills to bring them into the classroom. During the economic crisis in the United States, many migrant families returned Mexico with the children. Many of these young people were educated in the United States and are native English speakers. They represent a valuable linguistic resource for Mexico which should be leveraged to strengthen the PNIEB, and the authorities should create mechanism to recruit and train them.

- The SEP needs to communicate more clearly what is going on in the program. Unfortunately, since several years after its launch the national office has done a poor job communicating what is happening within the program. The most egregious example was during the spring of 2014, when the PNIEB was incorporated in to the Programa de Fortalecimiento de la Calidad de la Educación Básica (PFCEB), apparently because of budgetary considerations, but the reason was never well explained. Although the curriculum had not changed and the program was essentially the same except for a name change, the move generated significant confusion amongst the public and PNIEB teachers as to whether the program would continue or not. Given the SEP’s proclivity for launching and then abandoning programs during the next sexenio, it is not surprising that this lack of consistency has generated distrust amongst teachers. Given the current tools available on-line, there is no excuse for the office not to communicate to its teachers in a clear and timely manner about updates and changes in the program. As of August 2015, the program is apparently back to being known officially as PNIEB, but again, this has not been adequately communicated, and in many states it’s referred to by a local name, again undermining its identity as a national program.

When these problems can be adequately addressed, the program will be able to reach its full potential. More than making outlandish claims to grab attention and headlines – Inglés en México: Reprobado – the authors of the Sorry report should use their influence to contribute to building the educational structures that will allow the program to be successful.

In summary, the Sorry report was produced by a group of educational reformers and critics with political ties and connections to the media, notably Televisa, in order to critique the PNIEB program. The report is well packaged, but the research that they report is based on a flawed study. The main instrument seems to have serious validity issues, and the premise of the argument – making claims about the PNIEB program based on an evaluation of high school students who never studied in the PNIEB – is disingenuous. As educational researchers, we should strive to contribute work that illuminates rather than obfuscates issues of language teaching and learning. Nevertheless, the report has merits, especially in its public policy analysis. As educators committed to improving all Mexican children’s access to quality English language instruction, we should heed the authors’ call to have the PNIEB program guided by sound educational policy and planning and not political considerations. We should also contribute to the public debate about the PNIEB by adding our own voices to the discussion, as I hope this commentary article has done.

References

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among five approaches, 3rd Ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Davies, P. (2009). Strategic management of ELT in public educational systems: Trying to reduce failure, increase success. TESL-J, 13(3), 1-22.

Nation, I. S. P., & Macalister, J. (2010). Language Curriculum Design. New York: Routledge.

O’Donoghue, J. & Calderón Martín del Campo, D. (Eds.) (2015). Sorry: El aprendizaje del inglés en México. Mexico City: Mexicanos Primero.

Ramírez Romero, J. L. (Ed.). (2010). Las investigaciones sobre la enseñanza de las lenguas extranjeras en México: Una segunda mirada. Mexico: Cengage.

Ramírez Romero, J. L., Sayer, P., & Pamplón Irigoyen, E. N. (2014). English language teaching in public primary schools in Mexico: The practices and challenges of implementing a national language education program. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(8), 1020-1043.

Sayer, P. (2015). ‘More & earlier’: Neoliberalism and primary English education in Mexican public schools. L2 Journal 7(3), 40-56.

Sayer, P. & Ramírez Romero, J.L. (Eds.) (2013). MEXTESOL Journal – Special Issue for 2013: Research on the Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica. 37(3).

Strack, F., & Mussweiler, T. (1997). Explaining the enigmatic anchoring effect: Mechanisms of selective accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 437– 446.

Terborg, R., García Landa, L., & Moore, P. (2006). The language situation in Mexico. Current Issues in Language Planning, 7(4), 415-518.

Wright, W. (2010). Foundations for Teaching English Language Learners: Research, theory, policy, and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Casden.