Introduction

Research into Mexican undergraduate students’ writing has provided significant insights about their difficulties when writing a thesis, both in their native language and in English as an international language. Hidalgo (2010), for example, found that the problems that political science students encountered when writing a thesis in Spanish were due to a lack of previous instruction in academic writing, guidance from their professors, and socialization into the practices of academic literacy. Tapia (2010) found that students of a program in modern languages who were in the process of writing a thesis in English were aware of their lack of academic writing experience and benefitted from the use of constructivist methodologies to acquire new writing skills. Busseniers, Giles, Mercado and Luna (2010) examined the thesis proposals written by students of an undergraduate program in English language and concluded that students needed to participate in activities that developed their rhetorical awareness of disciplinary text types to be prepared to participate in the academic discussions of the field.

Other studies have found that very few of the Mexican students of English language teaching who completed a thesis, published their work (Encinas, Keranen & Salazar, 2010). Results reflect the scarce attention given to academic literacy skills in Mexican higher education (Busenniers, et al., 2010; Roux, 2006; 2008; Vidal & Perales-Escudero, 2010), and in part explain the scant publication in the fields of foreign language teaching and learning (Ramírez-Romero, 2007; 2010) and foreign language writing (Encinas, Keranen & Salazar, 2010). As a number of researchers have pointed out, more case studies of individual novice scholars need to be conducted to learn about their literacy skills and develop an agenda to teach them effectively (Busseniers, et al., 2010; Flowerdew, 2000).

The aim of this study was to explore the ways in which writing different academic genres and publishing helped an undergraduate student of applied linguistics learn about her disciplinary community and facilitated her initiation into that community. Research in academic literacy emphasizes the importance of discourse communities in shaping the genre knowledge of young scholars (Belcher, 1994; Swales, 1990). The following sections discuss the theoretical underpinnings of academic literacy and discourse communities.

The study of academic literacy

This study is based on a view of literacy as a set of social practices1 (Barton & Hamilton, 2000; Lea & Street, 1998, 1999, 2006; Street, 1995, 1996). Literacy practices are general cultural ways in which people use, talk about, and make sense of written language. Literacy practices are developed as scholars establish relationships with one another and share their ideologies and social identities (Barton & Hamilton, 2000). Academic literacy, viewed as a social practice, is not something that once acquired can be effortlessly applied to any context that requires mastery of the written word. Every time students write a paper, they have to construct knowledge about the object under study, the literature of the field, the anticipated audience, and their authorial-self (Bazerman, 1988).

From the academic literacies perspective, students’ difficulties when confronted with the writing tasks required in the university are not due to some sort of cognitive deficiency. Research has found that students’ difficulties come from the differences between academic literacies and other literacies students are familiar with (Barton, 2000); the dynamic, complex, and varied nature of reading and writing activities that students have to engage in as part of their studies (Lea, 1999); the gaps between student and faculty understandings of particular writing activities (Lea & Street, 1998); and the lack of opportunities students have to discuss their writing and the conventions they are expected to write within (Lillis, 1999).

Research in academic literacy has a specific ideological stance towards writing which can be described as transformative rather than normative. Normative approaches view the student population as homogenous, the disciplines as stable, and the teacher-student relationship as unidirectional. The interest of the teacher-researcher is in identifying academic conventions, exploring how students might be taught to become proficient in using them, and developing materials for that purpose (Swales & Feak, 2004). Although a transformative approach is interested in such questions, it is also concerned with locating the conventions in relation to contested traditions of knowledge making, eliciting the perspectives of student writers on the ways in which the conventions affect their knowledge making, and exploring alternative ways of meaning making in academia (Lillis & Scott, 2007). In this study I had a normative interest when inducing the participant into appropriate conventions and practices. I also explicitly discussed with her issues of power and authority to emphasize the contested nature of conventions. I will return to this point when presenting the results of the study.

The notion of discourse community

The notion of discourse community is widely used in the study of academic literacy to refer to a group of practitioners of a disciplinary specialty who share language, beliefs, and practices (Kuhn, 1970). Members of a discourse community function as “applied linguists” or “foreign language educators”, for example, because they share similar education and professional initiation; read the same literature; share goals and professional judgments; and communicate with each other successfully. Swales (1990) describes discourse communities as groups that have the same goals and use communication to achieve those goals. Central to his analysis is the notion of genre, the organizational patterns of written communication that pertain to specific discourse communities and help define those communities. Individuals who want to enter the discourse community of a discipline must learn the genres and conventions commonly used by its members (Bizzel, 1982) to participate in the conversations of the discipline, that is, the issues and problems current in the academic field at any one time (Bazerman, 1980).

The knowledge individuals require to write the genres accepted by their discourse communities is usually acquired as legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Legitimate because anyone can become a member of the discourse community; peripheral because participants are not central but on the margins of the specific activity; participation indicates that learners are acquiring the knowledge through their involvement with it. This kind of learning, however, is not a one-time process; it continues throughout the life of a scholar. Even experienced scholars need to go through the process of learning every time they write for publication. Scholars engage in legitimate peripheral participation by negotiating their position as members of a disciplinary community; their position is ratified when their article is accepted for publication. The conversations of the discipline (Bazerman, 1985) are ongoing and to maintain membership in a discourse community scholars need to engage in continual legitimate peripheral participation.

Young scholars also learn by legitimate peripheral participation when interacting with academic supervisors, working as members of research teams, submitting papers for publication, or communicating with journal editors and reviewers. Professors can use classroom time to provide students with opportunities to reflect upon and facilitate their legitimate peripheral participation, instead of using instruction for the transmission of knowledge.

The purpose of the study reported here was to examine the legitimate peripheral participation of a student of applied linguistics. Specifically, the study analyzed the participant’s process of writing a thesis and publishing. The study is part of a broader research project conducted to develop understanding of the perceptions, problems and strategies of Mexican undergraduate students of applied linguistics writing in English for academic purposes.

The Study

Purpose and context

The purpose of the study was to examine the academic literacy practices of an applied linguistics student. The aim was to learn about what she did with texts and what the writing activities meant to her as she made efforts to complete a thesis and publish to enter a disciplinary community. The context of the study was a research project seminar which was part of an applied linguistics undergraduate program. The program was offered by the school of education, humanities and social sciences at a Mexican public university that serves around forty-five thousand students, state-wide, in the northeastern corner of the country.

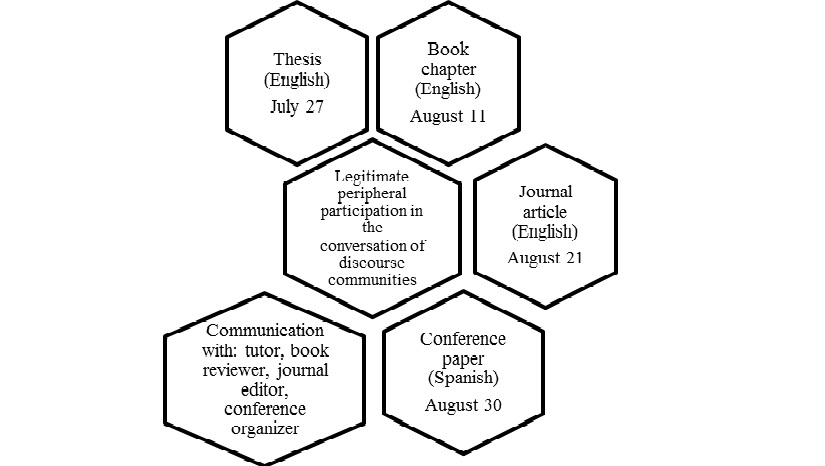

The study was conducted during an eight-month period in 2012. A young scholar referred to here as Ada (a pseudonym) was in the final year of studies and she was one of the very few students in her cohort who decided to write a thesis. She was also interested in publishing her work. She asked the author of this paper to supervise the development of the thesis. In the search for new ways of guiding students in the academic writing and publishing process, I took the opportunity to document the experience. Ada agreed to participate as subject for the case study. Her writing activities consisted of writing a thesis, writing a short book chapter on how to write a journal article, writing a journal article from the thesis for a Colombian journal, and writing a conference presentation from the thesis for a university student research conference. Only the conference presentation had to be written in Spanish. Figure 1. shows the participant’s writing activities.

Figure 1. Participant’s writing activities

Method

This investigation used case study methodology. To examine the participant’s academic literacy practices from a number of different perspectives and achieve an element of triangulation, I used several sources of data. One source involved the various drafts and final versions of the academic genres written by the participant. Other data sources were in-depth interviews (in Spanish) and email communication between the teacher-researcher and Ada; field notes and participant verification of the final report; correspondence between Ada and a book reviewer and a journal editor; and my continuous discussion about the case study with a research assistant.

Participants

Ada was a 23 year old student, born in a sugar cane producing town in the northeast of Mexico. She started the first four years of her elementary education in her hometown. When she was in fourth grade, she moved to the United States with her parents and siblings. Her father was given a job in the construction industry in North Carolina, where Ada continued her education through freshmen high school. During her years in the Unites States, she was member of a national career and technical student organization. She also enjoyed participating in academic development activities and she was given a distinction award for an essay on the importance of organic agriculture. After five years, her parents moved back to her home town and Ada entered a public industrial technology high school. During the last year of high school, she completed part of her social service2 by tutoring students who needed assistance in algebra. After finishing high school in 2008, she moved to the state capital city to dedicate full-time to undergraduate studies in applied linguistics.

During the first part of her last year of college, Ada fulfilled social service hours at a university research center. Her activities consisted in updating the library catalogue and helping out with translations for different purposes. On the second part of her last year of college, she started writing her thesis on the communication strategies used by two beginner level English teachers at the university language center.

It was clear from Ada’s account of her educational experiences in the United States that she felt benefited by the opportunity to learn how to read and write in English at an early age. She also expressed that she felt more comfortable learning in the undergraduate program where most of the courses were in English, than in high school, where all classes were taught in Spanish. During an interview she expressed:

In high school I constantly felt frustrated because of my difficulties to write in Spanish. When my first assignment was given back to me, all marked in red, I felt I was not going to make it through high school. Things changed, but I never felt comfortable writing in Spanish. A friend told me about this program with classes given in English. I thought, this is what I want, this is my place. (Interview 1, page 9)

The undergraduate program that Ada studied gave opportunities to students to write their thesis in English or Spanish. Ada did not hesitate in choosing English.

As teacher-researcher I was also a participant of this study. I have been an English language teacher for more than thirty years and in the last two years I have taught three courses: academic writing in English, teaching and evaluating writing, and research project seminar. It is my belief that one of my roles as university teacher is to demystify and democratize knowledge making. I view knowledge as something that is constructed rather than discovered. We construct our understanding from experience and from being told what the world is. As educators we can socially construct knowledge through collaboration with our students. Although we are not wholly peers with them, we can still be peers in the crucial sense of also being engaged in learning. Significant learning requires change and inner adjustment. We can increase the chances of our students being willing to undergo the necessary anxiety involved in change if they see we are also willing to undergo it. Collaborative research with our students redistributes power and authority so that it is not only “in our hands”.

Data collection

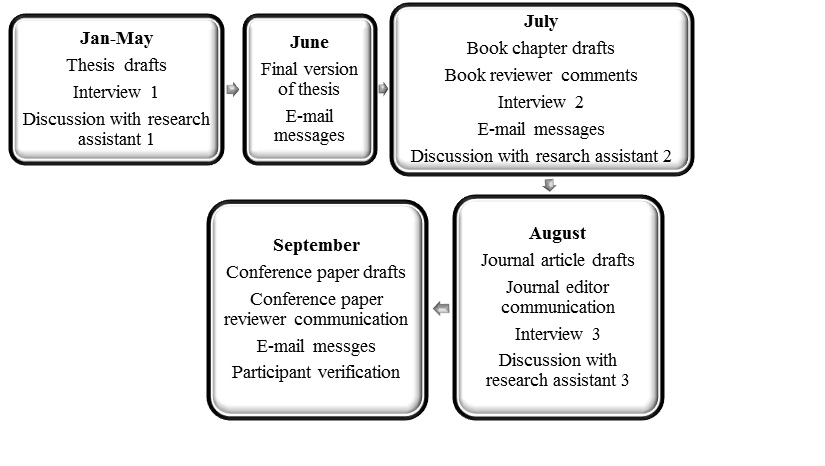

Data for the study were collected in an eight-month period that began with a research project seminar in the last semester of the applied linguistics program. From January to May, two drafts of the introduction, literature review and methodology chapters of the thesis were collected. From then on, data were collected every month. In June, book chapter drafts were collected and an interview was held. In July the book reviewer comments were collected and discussion with a research assistant was audio-recorded and analyzed. In August, two drafts of a journal article and the email message of the journal editor were collected. In September, two drafts of a conference-paper gathered, as well as the email message of the conference paper reviewer. In the same month, an interview was held with the participant to verify global results. Figure 2. depicts the stages in the data collection process.

Figure 2. Data collection process

Drafts were received by electronic mail. Interviews with the participant were held in a classroom, in the school library and in the researchers’ office. Discussions with the research assistant took place in the researcher’s office and in a coffeehouse.

Data Analysis

There is no formula for transforming data into findings (Stake1995). Analysis, however, is affected by the purpose of the study (Patton, 2002). This study aimed at learning the ways in which Ada acquired knowledge of the genres used in applied linguistics through her legitimate peripheral participation in discourse communities. To analyze the data, drafts, field notes and interview transcripts were affixed codes on segments of text that indicated how the participant solved different kinds of difficulties to complete her written papers. Notes and remarks were written on the margins, next to the codes. Then, the segments were sorted and sifted to identify themes, and to gradually elaborate a small set of generalizations (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Findings

Data collected seems to indicate that Ada went through a process of knowledge construction that included three major types of actions: negotiating with texts, constructing a writer identity, and acquiring genre knowledge. These actions were performed as she attempted to participate in the conversations of discourse communities. Each action involved different types of abilities that are described and illustrated with data in the following sections. Figure 3. represents a summary of the findings.

Negotiating with texts

Ada was a student in the research project seminar that aimed at guiding students in writing a thesis. The course was associated with two previous courses on quantitative research methods and qualitative research methods. The progress achieved by students in the seminar was mixed. All of them worked on different types of assignments that led to the completion of a thesis. However, they did not seem to be committed to doing their best because although the school in question promoted thesis writing as a desired mode of graduation and included three compulsory courses in the program to develop it, a variety of graduation options were also offered. Students could choose non-thesis options such as: high general point average, general knowledge exam, exit exam, graduation course, or even taking three master’s degree courses; all of them with an extra cost. This school policy results in most of the students submitting work-in-progress papers in the research project seminar, and selecting a different graduation option after the course is graded. Interview comments indicate that Ada was initially not planning to complete her thesis:

At the beginning I was just submitting papers on due dates to ensure a grade. I did not feel confident of my writing skills and um, having good grades um, made it easier for me to graduate by the option of high average. I did not want to go through the trouble of writing a thesis. I felt as if writing a thesis was something special, something different, something hard to do, that very few people could do. I did not see myself there. I never imagined myself writing a thesis. (Interview 3, page 2)

Ada was investigating about the communication strategies used by English language teachers in the classroom. By the end of the course in May, she had submitted the focus and significance of her study, some drafts of the literature review, and the methodology she wanted to use. She also had a set of audio-recordings of beginner English language classroom teacher-student interactions and interviews with two teachers. She still needed to analyze information, write results and conclusions, and go back to make all parts fit together into a thesis. We agreed to work during the two months of summer break so that she could start the paperwork for a thesis defense at the beginning of the following semester.

Ada worked diligently for two months. Communication through electronic mail with drafts and feedback were frequent. When I interviewed her she mentioned her writing had changed, and I prompted her to explain. She referred to the level of detail she noticed in her own writing. The following were her comments:

When I read my work I find it very different from the way I wrote last semester. My writing was mindless. Now I try to describe in detail, as in the articles I read, as in s-o-m-e of the articles, I should say. Some writers leave out important information. One has to be very careful synthesizing things in a way in which the essence of the research is not lost. When I read some of the articles, I had my doubts. I realized some had information missing. Some did not explain where the instrument came from, or where they got the taxonomy from, or who the participants were. And I thought, why does he use corpus? Why did he not observe directly to get more information? And then, when I was writing the methodology I did not want to leave my readers without all necessary information. What if they want to do something similar? I don’t want them to go into the trouble I went through (Interview 3, page 7).

Comparing old and recent drafts of her thesis confirmed that her writing had changed. Ada had learned from negotiating with texts that detail is necessary in academic writing. The following are two versions of the same segment of text:

|

From my perspective I found the topic of this research very interesting, and it is an aspect of the field that probably helps answer many questions when we encounter communication strategies. To be gender it, is in fact a factor that will definitely influence in communication. However, I do find this study somehow vague with lots of factors that are missing. Personally, when I read an article, especially from a topic that I would like to research on I would like to know everything about the process of the study.

|

Results indicated that the gender of the interlocutors definitely influenced the type of communication in which they got involved. However, the study seemed vague, with many pieces of information missing. First of all, the information about the participants was incomplete. The ages of the participants, the time spent studying English and their proficiency level were not described. Secondly, the article does not give a thorough description of the procedures of data analysis for those who want to replicate the study. In terms of the results, the communication strategies most and least used by the participants was also missing. Finally, the research questions were not clearly answered. |

Table 1: Two versions of Ada’s drafts

I also asked Ada what she thought made her writing change. Ada mentioned reading, a graphic organizer, a general overview article, and examples of academic language use that were provided during the course. The graphic organizer is a tool that I find useful for my own research and I have shared with my students in the research project seminar. It is a chart that has columns to fill-in with information from research articles (v. gr.: focus of the study, methods, and results). The tool is useful to synthesize the contents in research papers. A general overview article, on the other hand, combines summarized content from many specialized articles into one broadly scoped article. This type of articles is useful because it provides readers with easy access to a wide range of studies on a research topic. Finally, the academic language examples Ada referred to were feedback comments that consist in reformulating short segments of the student’s text in the margin, to show how an idea can be expressed in a more formal style. Although this type of feedback is not always well accepted by all students, Ada considered it useful. In the following excerpt of the interview she explains what made her writing change:

What changed my writing? I guess having to read a lot, and looking for details in the studies, filling the chart you gave us to draw forth the details of the studies. That helped me a lot. As I read more studies to fill in the chart I became more focused. Before I used the chart I got distracted with so much information. At the beginning I didn’t see many things in the texts, everything seemed important. Then I became more careful, I looked carefully at what I was going to use from each study. Who designed this? Or where did this come from? When I read the article you sent me about all the taxonomies, many of them, and I had to know about the one I was using, where it was coming from, who else had used it. That article with all the taxonomies was so good. Another thing that helped me is when you wrote on my paper my words in your words, remember? I thought, oh, it’s the same thing, but it looks better, you see, ideas can be said with different words, without changing the meaning. So, the same information can be expressed in a different way, in a more formal style. That is the most difficult thing to achieve, changing the style, writing more formally, I write more formally than before, I think. (Interview 1, Page 11)

During the seminar other resources were provided to students, such as the school handbook on how to write a thesis; theses written by other students; Web-sites on thesis writing; and different types of feedback (v. gr.: command, open question, close question, advice). None of those were mentioned by Ada.

Constructing a writer identity

While Ada was writing her thesis, she seemed to be more focused on dealing with language and texts, the ones she was reading and the ones she was writing. In the writing activities that followed, writing a book chapter and a journal article, she seemed to focus more on deciding how she wanted to represent herself on her writing. It was until she started writing to publish, that she became more concerned about whom she was writing to, what she wanted to tell them about her study and how she wanted to be perceived by her readers.

A few days after Ada sent her final thesis draft, I told her about the possibility of sending a manuscript to a journal for publication. She appeared excited. We agreed on searching the Internet for journals in which her article on the communication strategies used by English teachers in Mexico would fit. At that time, two colleagues and I were editing a book on research in English language teaching. The book was intended for teachers and student-teachers interested in understanding research and undertaking their own investigations. The book had three sections: the first one introduced the readers into the realm of research in English language teaching; the second provided examples of studies carried out in Mexican contexts; and the third section gave guidance on writing theses, conference papers and journal articles. I thought that before writing the journal article, Ada could benefit from writing the chapter on how to write a journal article. This would introduce her to the world of publishing and provide her with genre knowledge. She accepted the challenge and in two weeks she prepared a five page paper that summarized the content and structure of journal articles. It took another two weeks to review the paper. The whole process of writing the book chapter took place in July; the book would appear in November.

Meanwhile, Ada started to work on the journal article from her thesis. Writing the journal article became the peak of her learning curve; there was a change in the way she viewed herself. This could be interpreted from the following comments:

Writing a thesis was an achievement for me, something that I know is not easy to do. I had to collect data and then listen to the recordings a million times. I felt so tired, I spent hours and hours, maybe twelve hours or more. I had to listen and listen to make sure I had transcribed everything properly. After the transcription, things became easier. But a thesis is a requirement. Who is going to read it? I’m not that sure. They [the theses] are all in the library. The tutor and the examiners, that’s it. They will know that I worked hard. I´m happy because I´m one of the few in the program who has written one. That flatters me. But the article is different. Someone is going to read what you wrote; someone is interested in what you say. Many in other countries are going to see it and someone might even want to use it. Maybe someone with experience will read it. And it’s as if those people consider me as one of them. I have to put myself as someone that is more than just a student. I have to understand that it is not impossible to do research. And that’s why I need to be more careful. (Interview 3, Page 11)

Writing to publish gave Ada a different view of writing. She learned that a thesis is generally read by few people and that its purpose is to show that the writer knows everything about a topic. She also experienced the uncertainty of not knowing the readers and the anxiety of having to present findings that are relevant for them. More importantly, she understood that she had to present herself as knowledgeable.

Acquiring genre knowledge

Few students and teachers are aware of how much academic production can result from writing a thesis. As Ada observed, “If I hadn´t written the thesis, I wouldn’t have all that I have”. From the thesis she drew a journal article and a conference paper. Experimenting with those genres prepared her for diverse social interactions in the applied linguistics field. Genres are the means through which scholars communicate with each other. They disseminate the discipline’s methodologies and information in ways that conform to the norms, values and ideology that novice scholars need to learn. Understanding the genres of written communication is crucial for institutional recognition and the advancement of the profession. Academic productivity is also the criterion by which educational programs are evaluated. Thus, genre knowledge should be at the center of applied linguistics and English language teaching programs.

Ada wanted to include ‘everything’ in her first attempt to write the article from her thesis, as the result of the need to demonstrate her ‘scholarliness’. She later realized that her aim could be counterproductive to getting the manuscript published. She had to change the focus of the thesis to the findings and recommendations for a wider readership of teachers and students. She also had to move away from the theoretical and methodological depth required by the thesis supervisor and the examiners. Furthermore the paper had to meet the needs of the journal readers within a tight word count. Ada talked about her difficulties when writing the journal article. The following are her comments:

I had to follow the journal requirements in number of words, margins, and this was complicated. I felt anxious because I couldn’t synthetize the contents for the article. I knew, in theory, what every section had to include. I learned I have to avoid being unfocused, I have to go to the point. I can’t be repetitive either. It was complicated to reduce the contents to the word limit. It requires more work than simply summarizing a section of the thesis. I omitted a lot of what I had written in the lit review. I had to check several times what to include and what not to include. The number of words and the stress of submitting it on the due date, that was complicated. I was still making changes at the last minute.

Although she had written a book chapter on how to write a journal article, she noticed that it was helpful, but not enough. The book chapter forced her to read quite a number of sources on how to write a research article. However, when she actually wrote the research article she realized that the process is easier said than done.

To write the book chapter, I read so much on how to write an article, all sorts of information. I was not all that satisfied when I finished it, but it was just telling others how to do it, and I thought I was prepared to write one. It was not as easy as I thought, no, no, no, no, it was not the same. When you read about how to write it [an article] it seems very simple, but then when you try to do it, to make it understandable, to make it sound convincing, in the required number of words, you want to pull your hair off. For example, I had to include the objectives of the study, the procedures and the results and I had to do it without changing the meaning of the whole project, but I also had to follow the author guidelines. Until you do it you understand.

Ada made several revisions of the article before sending it to the journal. Her efforts were compensated when she received the following electronic message:

Dear Author,

As co-editor of Journal X, I'd like to take this opportunity to congratulate you on the selection of your article for our next issue of the journal. It must be very satisfying to know that all the time and effort spent on your work will pay off with its publication.

I’ve enclosed the peer review for your article. The next step in the process as we move toward publication is for the contributors to go over the content suggestions made by his or her peer reviewers, and decide whether or not to make the suggested changes. If you, as a contributor, agree to the suggested changes, we have a deadline of Friday, August 21, 2012 of this year for you to resubmit your work with the new changes included.

The decision to make the changes is, of course, entirely up to the contributor. However, for the article to be published in Journal X, these changes will have to be made. If you decide you do not wish to make these changes, we ask that you inform us no later than August 17,2012 so that we have a clear picture of which articles we will be working with for our next issue.

In your case, your peer reviewers have given your article their approval, and it looks excellent, so you do not need to make any content changes.

Again, congratulations on the acceptance of your work. Our editor is available for any questions you may have regarding the editing and polishing of your article. Please do not hesitate to contact us.

Sincerely,

XX

The electronic message was evidence that Ada was beginning to participate in the conversations of the field. Her knowledge of the genre was understandably incipient; she knew what other authors were saying, the points they are making. She was also adding some detail to the ideas accepted by more experienced or central members of the community. This is probably the way most notable writers in the field began their now generative participation. The vicarious participation of Ada was reflected on the peer review checklist that accompanied the letter. The review was the following:

Table 2: Peer review checklist

The final part Ada´s academic literacy experience was writing a conference paper. By the end of August I received by electronic mail a call for participation in a student research conference, organized by the research department of the university. I forwarded the mail to my final year students and Ada responded promptly. She was ready to put the article into a five page conference paper. We both thought the process would be much easier. A new challenge became manifest: the paper had to be written in Spanish. Ada completed the work on time, however, baffled. The following were her comments in relation to writing the conference paper in Spanish:

It was just tedious having to write in Spanish. For me it is easier to write in English, I never had good spelling, I don´t know the rules. It’s not that I can’t do it, but I don’t like it. I did most of my beginning school years in the United Sates and I had a hard time in high school, when I was back in México. I didn´t know much of history, literature, language. I was lost most of the time, I didn’t like it. Writing again in Spanish reminded me of all that. Next time I will write one for the Mextesol conference, in English!

Ada’s knowledge of the conference paper genre, however, seemed most valuable. She followed the guidelines strictly from the beginning. She wrote a minimal introduction, limiting the scope of the paper, using only literature that was crucial to the research topic, and emphasizing the research methodology and findings. Ada included only the charts and tables needed by the reader to understand the topic of the paper. She also reduced the reference list including only those sources that were most relevant to the article and the audience. Ada gained familiarity with the widely accepted characteristics of the content, structure and style of a conference paper.

Conclusions

This case study explored the literacy practices of a young scholar at the end of her undergraduate degree studies and the beginning of her academic career. She was invited by her tutor to publish from her thesis and it became the most rewarding experience for both, despite institutional policies that diverted the attention of professors and students from academic literacy practices, and promoted market-like behaviors.

Writing for publication requires different skills to those learned in writing a thesis, most notably the ability to identify and meet the requirements of the readership of a particular academic journal. A thesis is written for an audience of two or three professors, while a published paper is read by many practitioners and researchers. Ada managed to write a variety of manuscripts in a relatively short period of time. Her academic writing was relevant to specific readerships and her style met expectations.

Writing to publish from a completed thesis is neither easy nor a skill most newly graduated students possess. It takes determination to learn new skills. However, publication can maximize the outcome of all the energy spent in a thesis, and lead to the development of new research skills and personal satisfaction. One aspect that seemed particularly motivating for Ada was being the first author and her tutor the subsequent author.

Ada seemed to be in a privileged position compared to her peers in the applied linguistics program because of her greater exposure to English at elementary and middle school in the United States. Her English, however, could be perceived as nonstandard by editors and reviewers of journals of the “center” countries. Her Spanish may also be considered non-native by Mexican journal reviewers. Fortunately, a whole range of journals in a variety of peripheral countries are now available which accept manuscripts written in English as an international language.

Then notions of discourse community and legitimate peripheral participation proved to be relevant in the study of academic literacy because they emphasize the negotiable and participatory nature of learning. These notions, however, are not incompatible with formal instruction. On the contrary, a challenge in apprenticing young scholars to the applied linguistics and English language teaching communities of practice involves enabling them to utilize and reproduce the discipline’s communication artifacts so that they can participate in the conversations of the discipline.

Notes

[1] The term practice, in social practice,is not used in the sense of learning something by repetition. The notion of practice refers to the cultural ways of using reading and writing, and the ways in which people talk about and make sense of the written language (Barton & Hamilton, 2000).

[2] Social service is a mandatory, practical,supervised, non-paid work experience in Mexican middle school and higher education.

References

Barton, D. (2000). Researching literacy practices. Learning from activities with teachers and students. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (167-179). NY: Routledge.

Barton, D. & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (7-15). NY: Routledge.

Bazerman, C. (1980). A relationship between reading and writing: The conversational model. College English, 41, 656 661.

Bazerman, C. (1985). Physicists reading physics: Schema-laden purposes and purpose-laden schema. Written Communication, 2, 3–23.

Bazerman, C. (1988). Shaping written knowledge: The genre and activity of the experimental article in science. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Belcher, D. (1994). The apprenticeship approach to advanced academic literacy: Graduate students and their mentors. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 23–34.

Bizzell, P. (1982b). College composition: Initiation into the academic discourse community. [Review of Four worlds of writing and Writing in the arts and sciences]. Curriculum Inquiry, 12, 191–207.

Busseniers, P., Giles D., Núñez, P. & Rodríguez , V. (2010). The research proposal at the BA in English of a major public university in east Mexico: A genre and register analysis of student writing. In M. D. Perales-Escudero (Ed.), Literacy in Mexican higher education: Texts and contexts (pp. 36-73). México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Encinas, F. & Keranen, N. (2010). Curriculum design and ELT university sector writing: Responding to global factors interpreted by local players. In M. D. Perales-Escudero (Ed.), Literacy in Mexican higher education: Texts and contexts (pp. 9-35). México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Encinas, F., Keranen, N. & Salazar, G. (2010). An Overview of writing research in Mexico: What is investigated and how (pp. 8-24). En S. Santos (Ed.), EFL writing in Mexican Universities. Mexico: Universidad de Nayarit.

Flowerdew, J. (2000). Discourse community, legitimate peripheral participation, and the nonnative-English-speaking scholar. TESOL Quarterly, 34(1), 127-148.

Hidalgo, H. (2010). Higher education in Mexico and its writing practices: the role of literacy. En S. Santos, (Ed.), EFL writing in Mexican universities: Research and experience (181-208). México: Universidad de Nayarit.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lea, M. R. (1999). Academic literacies and learning in higher education. Constructing knowledge through texts and experience. In C. Jones, J. Turner, & B. Street (Eds.), Students writing in the university (103-124). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lea, M. R. & Street, B. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157-172.

Lea, M. R. & Street, B. (1999) Writing as academic literacies: Understanding textual practices in higher education. In C. N. Candlin & K. Hyland (Eds.), Writing: Texts, processes and practices (pp. 62-81). London: Longman.

Lea, M. R. & Street, B. (2006). The “academic literacies” model: Theory and applications. Theory into Practice, 45(4), 368-377.

Lillis, T. (1999). Whose “common sense”? Essayist literacy and the institutional practice of mystery. In C. Jones, J. Turner, & B. Street (Eds.), Students writing in the university (127-147). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lillis, T. & Scott, M. (2007). Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 5-32.

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ramírez-Romero, J. L. (2010). Las investigaciones sobre la enseñanza de las lenguas extranjeras en México: Una segunda mirada. México: Cengage, UNISON, UAEM, UAEH.

Ramírez-Romero, J. L. (2007). Las investigaciones sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en México. México: Plaza y Valdes, UAT, BUAP.

Roux, R. (2006). Los usos de la escritura en los estudios universitarios: Géneros discursivos y principales dificultades. Paper presented at the III International Conference on Teaching in Higher Education. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, México.

Roux, R. (2008). Prácticas de alfabetización académica: Lo que los estudiantes dicen de la lectura y la escritura en la universidad. En: E. Narváez Cardona y S. Cadena Castillo,Los desafíos de la lectura y la escritura en la educación superior: Caminos posibles, Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, Cali, Colombia. ISBN: 978-958-8122-69-4.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Street, B.V. (1995). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Street, B. (1996) Academic literacies. In D. Baker, C. Fox, & J. Clay (Eds.), Challenging ways of knowing: Literacies, numeracies and sciences (pp. 101-134). Brighton, United Kingdom: Falmer Press.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (1994). Academic writing for graduate students. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Tapia, R. (2010). Thesis writing and professional development beliefs. En S. Santos (Ed.),EFL writing in Mexican Universities, (209-238). México: Universidad de Nayarit.

Vidal, C. & Perales-Escudero, M. D. (2010). Writing tasks in a pre-service English teaching program: Professors’ beliefs (pp. 154-190). In Perales-Escudero, M. D. (Ed.), Literacy in Mexican Higher Education. Texts and contexts. México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.