Introduction

The ultimate goal of any research is knowledge dissemination and sharing its findings with the academia. Communicating ideas should be accomplished, in the words of Shah et al. (2009), quite “accurately and effectively” (p. 511). Mastering such skills especially for novice researchers is deemed necessary if they are to reach the international communities and get published in top-tiered international journals. By the same token, advancement of knowledge is facilitated with attempts on the part of the researchers to familiarize themselves with the generic conventions, a goal aimed by genre analysis (GA) studies. Indeed, with the objective of surveying the method section of applied linguistics mixed methods research (MMR) articles, Hashemi and Gohari Moghaddam (2016) conclude, “becoming conscious of such intricacies in the generic structure of MMR articles can be very useful for researchers and authors. By developing their discursive competence, authors can communicate more effectively in their communities of practice” (p.11).

Notably, graduate students in applied linguistics are under a lot of pressure as they are required to publish as a partial requirement to complete their studies. To be granted permission to defend their dissertations, Iranian PhD students are required to publish a paper extracted from their dissertation in the Science Citation Indexed (SCI) Journals, and MA students receive an added bonus mark if they publish a research article (RA) before graduation. In this sense, the RAs are the benchmark of academic writing for these students to the extent that Hyland and Jing (2017) consider “published research articles as the most important genre of academic writing” (p. 41).

To publish a manuscript, the researcher needs to be familiar with the subject matter as well as the writing conventions practiced in the field. For non-native students, the challenge of getting published becomes even more serious to the point that Van Djik (1994, cited in Flowerdew, 2001) proposes “the triple disadvantage of having to read, do research and write in another language” (p. 78). Mastery and adoption of the literacy practices, as Zhang and Cheung (2017) state, are needed for early researchers to be permitted into the communities of practice in the field.

For Miller (1984), genres “serve as keys to understanding how to participate in the actions of a community” (p. 165). Additionally, in Martin’s (1993) words genre is “a category that describes the relation of the social purpose of the text to language structure” (p. 2). As Bhatia et al. (2008) have said, genre studies may go beyond the linguistic level and “offer explanation for specific uses of language in conventionalized and institutionalized settings” (p 10). In fact, moves refer to the communicative purpose of a text segment, with the specific rhetorical choices realized as steps. Therefore, a text is formed through a series of moves and steps that could be obligatory or optional and could appear in a variety of stages or sequences.

Acquisition of genre knowledge by students translates into learning the rules of the game. Otherwise, they may be identified as outsiders and incompetent writers (Flowerdew, 2001). Following the conventions guarantees clarity and provides a smoother organization of the paper on the part of the writer and reading, understanding, and evaluation of the research on the part of the reader. How learners acquire these rules and conventions, as practiced by community users to produce academic genres, has been a hot line of research for some time. Importantly, Hyland (2004) enumerates the strengths of a “genre-based writing instruction,” as being “explicit, systematic, needs-based, supportive, empowering, critical, and consciousness raising” (pp. 10-11). By identifying the common structure of RAs in most academic fields and creating a relationship between the text features and their underlying objectives built up systematically through a series moves, genre analysis GA studies play a contributing pedagogical role. A thorough description of the macrostructure of rhetorical stages and their linguistic features helps to clarify the complex nature of academic literacy for non-native scholars who wish to contribute to the world of knowledge (Sheldon, 2013).

Staples and Reppen (2016) open their article with reference to research calling for more intervention studies being conducted “within the context of writing classes” (p. 17). Along the same line, discussing intertextuality, Flowerdew (2013) calls for future research projects in awareness raising among learners. Being conducted in the context of classroom and aiming to trigger learner consciousness, this study addresses both gaps. Still more, what is missing is research on how the Introduction-Method-Results-Discussion (IMRD) structure may be used to alert students’ attention to apply it in their writing. A detailed account of the steps taken in the classroom could help novice teachers to practically implement Genre-Based Instruction (GBI). Besides, a GBI benefitting from students’ reflective voice messages is missing from the literature. In an attempt to apply a GBI in a classroom context by highlighting the features of RA sections written in multiple drafts, and to explore student reflections on GBI, this study adopted Swales’ (1990) IMRD framework. Not only do the findings of this study assist to bring about progress for students’ academic writing skills by heightening their awareness, but the results also aid them to incorporate these features into their writing and to gradually and ultimately change into more genre-conscious academic readers.

Genre Teaching/ Learning

In her much-quoted article, Hyon (1996) lists three approaches to genre teaching:

- Systemic Functional Linguistics, which is interested in the rhetorical organizations.

- The New Rhetoric Approach, which enjoys a more social orientation and focuses on the functional and contextual aspects of genre.

- The ESP perspective, which is interested in genre as a means for teaching discipline-specific writing in academic settings.

As the leading figures in ESP approach, Swales (1990) and Bhatia (1993) define their main objective as helping non-English major and non-native students to write academic RAs. Characterizing and introducing the communicative moves of articles in a given discipline, they propose, will aid the students follow the patterns and fulfill their objectives.

Forming the theoretical background for the present study, ESP research views genre as a class of communicative events in a discourse community in order to fulï¬l a speciï¬c purpose. Writing the abstract of a paper, for instance, the author has to observe the necessary moves to communicate as precisely as concisely with the reader as possible. For Tardy (2016), “Exclusion of genres from the classroom is not really an option, as they are the primary means through which humans communicate in writing” (p. 129). Though the instruction of genres is criticized on the grounds that this freezing prescriptivism kills creativity, genre teachability is touted as it raises awareness and triggers sensitivity to conventions among students (Bhatia,1993; Tardy, 2016; Yang, 2012). Analyzing the RAs for use of informality across disciplines and over different time spans, Hyland and Jing (2017) discovered that surprisingly even the published scholars show a preference for following the generic rhetorical patterns. Accordingly, attempts to trigger learner awareness on the organization of the RAs with particular emphasis on moves and steps deserve the due attention.

Previous Studies

The researcher found three articles of utmost relevance to the current study. The earliest is an 18-week genre-based approach (GBA) to teach EFL learners and detect their views on the instruction in the context of Taiwan. Yang (2012) maintained that the study meant “to build genre knowledge” (p. 58) and reported raising learner’s confidence. However, merely the leaner’s attitude is delineated and the given instruction is left untouched. The present study, similarly, opts for learner’s view on the GBI but pays particular attention to the specific class events.

In the second study, following a genre-based instruction, Wang (2017) attempted to prepare eight MA students to write their prospective theses within a 17-week intervention. The data sources were interviews, process logs, and written texts for the course. Overall, two features were identified “self-direction” and “self-positioning”. In the former learners “make their own decisions in response to and despite explicit instruction and teacher’s feedback,” and in the latter performing the tasks, the learners show “a significant deviation from the expectations of the course instructor and the task design” (p. 56). Wang (2017) took more interest in student’s response to the instruction with more focus on learner characteristics. This study, on the other hand, probed the produced text features.

The third study belongs to Kelly-Laubscher et al. (2017) which was conducted with biology students undergoing an intervention of “the pedagogical genre of the laboratory report” (p. 1) in South Africa. With respect to the extent of writing improvement, a statistically significant difference was reported in the introduction, method, results, discussion, general, and references between the first and second drafts. Moreover, successful understanding of the genre is apparent. According to Swales (2004), the reported study takes a more process-based approach and delves into the “highly complex dynamic,” features of “the whole process of moving from notes and other forms of data to first draft to final draft” (p. 218).

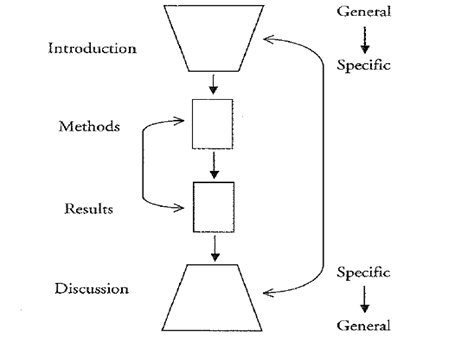

GA studies paved the way for teaching academic writing. Swales’ (1990) ground-breaking IMRD structure, thus, offered the scholarly world a prototypical structure to work with. In this framework, the RA comprises four sections of Introduction, Method, Results, and Discussion (Swales & Feak, 2012). In the Introduction, the author aims at introducing the topic, attracting the readers’ attention, identifying the gap by reviewing the literature, among other purposes. The Method section elaborates on the participants, instruments, and the procedure of the study. In the following section, as the name suggests, the findings are reported; and finally, the results are interpreted and conclusions are put forward in the Discussion section. A close relationship, as Swales and Feak (2012) suggest, exists between the introduction and conclusion of the RA; in much the same way, the method and results sections are closely interrelated. The literature is replete with research validating the IMRD model across various disciplines and different RA sections (Introduction: Swales & Najjar, 1987; Method: Peacock, 2011; Results: Brett, 1994; and Discussion: Holmes, 1997).

As stated by Lave and Wenger’s (1991) situated learning, education should not be viewed as simply a transmission of abstract and decontextualized knowledge from one individual to another but within a social context where knowledge is co-constructed. Taking little interest in the cognitive processes involved, the followers of this theory ask what kind of social engagement provides the proper context for learning to take place, that is, learning identical to the context in which it is applied. Situated learning provides authentic contexts and activities. In a comprehensive list, Herrington and Oliver (2000) offer a set of tips to help teachers actualize situated learning environment. In doing so, teachers refer to some features characterizing this setting: defining tasks and subtasks, creating chances for collaboration and sharing, designing group and individuals tasks so that the topic is tackled from various angles, and having the teacher available for “coaching and scaffolding” (p. 27). Notably, apart from fostering deep learning, situated learning encourages student engagement. Therefore, in the current study the relationship between the teacher and the learner is viewed in this light.

As newcomers to the EFL community, novice researchers are recommended to complete a training period to familiarize themselves with the necessary skills and knowledge and to reach the ideal point where to view themselves as part of a community of professionals. With this aim in mind, and drawing upon the features of situated learning theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991), the researcher planned a GBI in the Advanced Writing Course for MA students in TEFL. The following research questions are addressed.

- What are the features of research article sections written by students prior to and after receiving a genre-based instruction?

- What are these students’ views on genre-based instruction?

Method

Participants

The data were collected over a time span of four months in the spring semester of 2018 in an advanced writing course, taught by the researcher, designed to increase twelve Iranian male and female MA TEFL students’ rhetorical awareness of writing RAs for an English-speaking target audience. Being in their first semester, the students had no systematic prior instruction in academic writing in English and could be categorized as novice writers.

Procedure

During class time, 90 minutes for 14 sessions, attempts were made to direct the student’s attention to the organization of RAs, with particular emphasis on the moves and steps, relying on Swales and Feak’s (2012) tasks. A large share of class time was devoted to detailed discussions and elaborations of the rhetorical features of the scholarly articles and the moves and steps employed. It was assumed that this approach would help to form students’ repertoire so that they could observe these moves and steps in their own written products. Similar to Cheng (2008), who analyzed genre exemplars in preparation for writing, the researcher worked with samples. As a result of repeated exposures to select samples, the students’ generic repertoire of the features of the RA sections, realized as moves and steps, would expand.

Moreover, following Flower and Hayes (1981), the tasks were designed to encourage critical reflection and mindfulness. A “visible pedagogy”, as Hyland (1998) notes, seeks to offer writers an explicit understanding of how target texts are structured and why they are written the way they are. To heighten awareness of the functions of the generic features, as led by Swales and Lindemann (2002), the students were directed to answer the following questions while they were doing the tasks:

- What was the author trying to do with these sentences?

- What are the words, phrases, or sentences that the author used to achieve this purpose in the samples?

- Why do you think the author chose to structure the RA in this way?

In-Class Events

Intervention

To introduce the students to the genre of the RA, they were guided through the IMRD format. The intervention, tailored to scaffold the learners and to gradually lead them to act more independently, consisted of three parts: lecture series, in-class, and out-of-class group and individual genre tasks. In the course of the lecture periods, the students were scaffolded, and I was continuously available to respond to questions and facilitate discussion. As they were doing in-class tasks, I joined their group discussions to elaborate on the confusing points. They were required to highlight the moves used in each section. For example, in one of the groups working on the task of moves in the abstract, they could not reach an agreement on “the background move”. Therefore, I clarified the issue to help them resolve the problem. During the intervention, I had in mind Flower and Hayes’s (1981) notion that in completing tasks, the learners should move beyond mere naming and identifying, and need to end with appraisal and meaning creation. Explicit moves identification, understanding the relationship between different sections, and evaluation, the researcher thought, would boost students’ generic competence. To avoid an overly prescriptive approach, the students were repeatedly reminded that these features were more of options than set of rules.

Lectures

Primarily, building upon the 3-part essay structure, the researcher embarked on the similarities between the introductory, body, and concluding paragraphs of the essay and the different sections of the RA, relying on Swales and Feak’s (2012) schematic representation given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overall Shape of a Research Paper (From Swales & Feak, 2012. p. 285 )

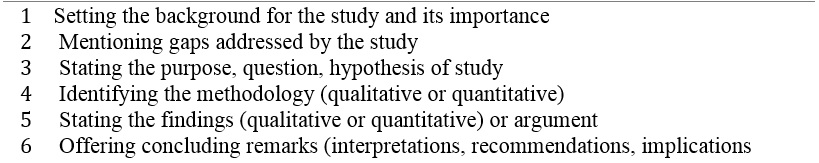

Session two started with the analysis of move-step structure in the abstract. Drawing upon Tessuto’s (2015) neatly organized list, as shown in Table 1, the moves in the abstract were introduced.

Table 1: Distribution of Moves in the Abstract (Tessuto, 2015. p. 19), Permission Granted by Elsevier

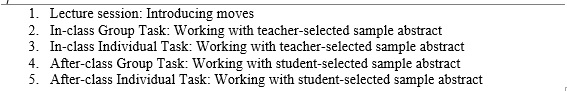

Group and Individual Tasks

The students were next given the opportunity to work with a partner(s) and to practically apply what they had learnt in the lecture session. The hard copy of a sample abstract was distributed to the students and they were asked to identify the moves while the slide on “the abstract moves” was being played on the screen. As for the selection of the materials, care was taken to include articles that were sufï¬ciently concise to ï¬t within the available class time. For each task, the procedure was to begin with the teacher lecture, followed by in-class group and individual tasks. The following session, class time was devoted to student presentations of the RA sections of their own choice from the recommended list of journals delivered in groups and individually. For their group work, the students were designated to different groups, based on their own preferences.

Having introduced and discussed the moves in the abstract, the students were then assigned to work in groups on a sample abstract in order to explore, identify and, evaluate the moves. In the early stages of the course, an attempt was made to choose the samples from journals with wider scope of readership and consequently containing less technical and complicated topics. The following abstract by Lenkaitis and English (2017) published in MEXTESOL Journal, was selected as a sample.

Utilizing Walker and Baets’ (2009) Instructional Design Framework, this study qualitatively investigated the utilization of technology as a means to introduce cultural context in small group learning activities to support second language learning (L2) in the classroom. Five intermediate-level learners of L2 Spanish (n = 5) worked in groups via Zoom, a video conferencing tool, to complete activities based on their understanding of a telenovela (soap opera), La Reina del Sur, in the Spanish language. By analyzing pre- and post-surveys of all participants’ opinions regarding technology, culture, and group work as well as the coding of two groups’ Zoom transcripts with NVivo 10 software, this study investigated whether exposure to the L2 culture, via technology, influenced L2 learners. Also, this study examined online small group work activity (Pica 1991, 1994; Long, 1996; Gass, 1997) and in what ways media and technology impacted L2 participants’ interaction in this medium. Although participants identified the areas of difficulty with understanding the telenovela in the post-survey, participants also commented that they improved in language skills and culture from participation in the telenovela activity. Results from the coding of Zoom sessions revealed that students benefitted from small-group work and exposure to the target language’s culture through the integration of technology. Although results revealed that learner engagement can decrease when a leader in the group emerges, they also revealed that minimal contributions are meaningful (p. 1).

As a result of working with this sample, the students discovered how moves and steps are realized in a given abstract. This was evident from their analysis of the other sample abstract done immediately after that; less effort was put into the task. Additionally, the participants’ questions and comments suggested that they were successful in working with the moves. Some of their questions follow:

Is the sequence of moves always observed?

Is it possible not to have a particular move or step?

Is there necessarily a one-to-one correspondence between the moves/steps and sentences? I mean could two or three sentences function as ONE move or step?

The discussions among students also denoted that they reached to an agreement within a shorter interval. As for the Introduction section of the RA, following my introductory comments, the students were provided with the introduction of a RA. First, they had to identify the moves in the model introduction in teams. Another sample introduction was distributed to the students to characterize the moves and steps based on the model slide on the screen. Finally, they were assigned to do out-of-class tasks. Similar to what they did in the abstract phase, the students were required to select a RA and focus on the Introduction section, highlighting the moves and steps both in groups and individually. It should be noted that an almost identical sequencing of tasks was practiced in addressing the other sections of the RAs, i.e., Method, Results, and Discussion. Tessuto’s (2015) Table which neatly summarizes the moves and steps on all RA sections, was shared with the students throughout the course (Appendix B).

Table 2 displays the procedure followed in class regarding the abstract moves.

Table 2: Sequence of Tasks for Abstract Moves

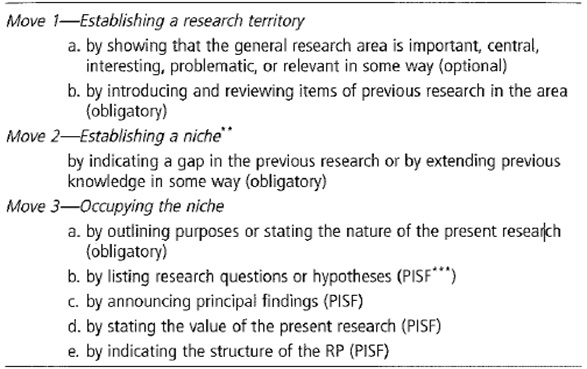

The CARS model, which deals with the Introduction section of the RAs, was presented in a new session. The teacher/researcher elaborated on the moves listed in Figure 2 to clarify the model. To embark on the discussion of the first move of “establishing a research territory”, the researcher found the General-Specific pattern observed in the Introduction section of Figure 1 of great help. The students realized that some steps were obligatory while others were optional. Even more significantly, the students could tell some steps were, to borrow from Swales and Feak (2012), “PISF=probable in some fields, but rare in others” (p. 331). In the same way, the procedure summarized in Table 2 was followed in this phase. Working with a Sample Introduction section (See Appendix A[1]), the instructor presented the moves and steps in this section of the RA.

Figure 2. Moves in Research Paper Introduction. (From Swales & Feak, 2012)

Out-of-Class Tasks

Group and Individual Tasks

Following Cheng (2008), the learners were encouraged to choose five articles of their choice published within the previous five years in the recommended journals and present them to the class in groups, to critically evaluate the author’s intention in the employed moves and the organizational patterns. They were instructed to seek my advice when selecting the RAs. The most frequently cited journals in applied linguistics studies formed the logic for journals selection (For details see Hashemi & Babaii, 2013). The recommended journals were ELT Journal, English for Academic Purposes (EAP), English for Speciï¬c Purposes (ESP), Journal of Asia TEFL, MEXTESOL Journal (MJ), The Modern Language Journal (MLJ), RELC, System, TESOL Journal (TJ), and TESOL Quarterly (TQ). Students were also recommended to make their first choices from the ELT, MJ, and RELC, the rationale being the optimum length, the more practical scope and thus more graspable nature of the articles that all put together made excellent examples for the purpose of the current study. The teacher/researcher provided feedback on students’ out-of-class tasks and presented the commonly repeated flaws, trying to include all problematic points.

Having prepared the out-of-class tasks and worked with different samples, the students ascertained that not all moves introduced in the abstract were always presented. They were excited to find out that published authors follow the conventions in preparing the abstract, a point congruently raised by Hyland and Jing (2017). Besides, they figured out that abstracts might include citations. More importantly, they found out that the theoretical articles followed a different pattern. It should be added, though, that it was not easy to explain to the students why some authors decided not to include certain moves in the abstract. A similar procedure was pursued for the instruction of the Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion sections.

Mini-Projects

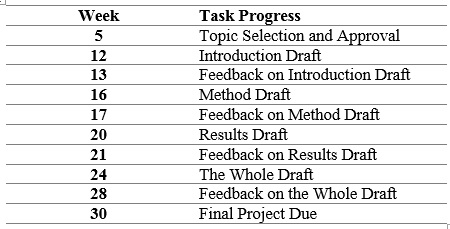

Up to this stage, the students had produced little, if any, material. In the next phase, they were required to attempt their own mini-projects, to be submitted as part of the course requirements. The difficulties of running research coupled with the challenges of academically reporting it was too much of a burden for these junior researchers. Mini-projects came as the best solution at this stage of research. As a result, the project required them to conduct a study of a limited scope and report it following the generic structure of the RA. Having chosen the topics for their projects under my guidance, they were to progressively submit their multiple drafts on Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion sections by the due date. Once they received my feedback, the students revised the sections and this led to the step-by-step formation of their mini-projects due 4 months after the final exam. It should be noted that these students had another course with me in the following semester. We met every week and the interaction with the students continued. Table 3 shows the specifics of the project submission.

Table 3: The Mini-Project Timeline

The steps the researcher took to heighten student awareness of the generic features of the RAs have been explained.

Voice Messages

Johns (2011) believes that teachers “need to encourage … critical reflection that augments student ‘mindfulness’ or metacognition … leading, if possible, to high transfer of their thinking and learning to new, or evolving, genres, writing processes, and writing contexts” (p. 63). Moreover, in order to generate as wide and informative a range of responses as possible, the researcher planned to ask for reflective voice messages. The students recorded their voices using their cellphones and shared them with me via WhatsApp. This was set as part of out-of-class assignments to be prepared within five hours of each session. Voice messaging was used from session three on, for a total of twelve times. They had to send minimum ten posts of one minute each. The students were provided with the following prompts:

- “Think back to everything you did in your writing classes this week. Write some notes about what you experienced, thought about, and felt while in class” (Han & Hiver, 2018, p. 48).

- Verbalize what you experienced, thought about, and felt while in class or doing the out-of-class tasks.

- Share with me the problems, difficulties, or challenges you came across doing the assignment.

- Discuss any features of the instruction. Did you find it useful, interesting, or boring?

First, a research assistant transcribed the voice messages. All the 167 entries (2119 seconds) were then imported to the NVivo 12 software. “Word-by-word” or “micro-analysis” approach (Strauss & Corbin, cited in Moghaddam, 2006) was not adopted as it takes a long time to code the data and there was also the risk of becoming lost in the data (Moghaddam, 2006). Instead, the researcher decided to work with the key points and uncover themes. Starting with open coding, where the data are grouped and classified; the researcher read and reread the transcripts iteratively to discover recurring themes. Axial coding, which is an attempt to establish a connection among the “core categories” followed. Selective coding, referring to discovering a relationship among the codes, was finally run.

Results

This section reports the findings and the prevailing features and problems identified.

Attempting to answer the first research question, the features of students’ projects submitted in various drafts and the traced changes are described. The RAs the students selected for their out-of-class tasks were mainly of empirical and quantitative nature that are representative of the articles typically submitted by the students.

Introduction:

Too broad: Writing the introduction section, the students started too broadly. This made the movement to “purpose statement” to “occupy the niche” very abrupt. Reviewing the problematic parts in non-native contributions to international journals (Flowerdew, 2001), the journal editors refer to a similar flaw,” they begin 600 years ago or something. . . . Well, we’re only interested in the last 5 years or so” (p. 137). The first sentence of the “Introduction” of one of the students on a paper entitled: “Plagiarism and Technology for TEFL Students,” reads:

Plagiarism is not a new concept. Appreciating originality and abhorring plagiarism is in vogue in Europe since the 18th century.

For a paper of 2500 words, this is a very broad start! The writer needs much more space to smoothly get to “purpose statement.” The researcher resorted to the inverted triangle image to clarify the smooth general to specific movement in the introduction. When it came to the final draft of their mini-projects, narrowing down is more appropriately done. Upon receiving the feedback, the same student begins with a narrower, more relevant sentence.

Nowadays because of easy access to the electronic files, the students are easily tempted to plagiarize.

Secondary source overuse: A dominant flaw was secondary source overuse. Preparing the Literature Review, the students found it much easier to make reference to a given source without directly accessing that. Sometimes, a student made repeated references to ONE secondary source in their projects. In such cases, the student was strongly urged to access the original source if it was of utmost relevance to the study. In two consecutive paragraphs, a student referred to four secondary sources.

Graddol (as cited in Clyne & Sharifian, 2008, p. 2); Van der Wende as cited in Taylor, 2004, p. 4); Beauchamp (as cited in Su, 2012, p. 153), Wiggins and McTighe (as cited in Richards, 2013, p. 6).

In such cases, the student was recommended to access the original sources and minimize using secondary sources. Having been briefed on the significance of working with primary sources, the students were more committed to using original primary sources.

Integral/Non-integral citation imbalance: With regard to in-text citation, the imbalance between integral and non-integral citation was conspicuous. In the following paragraph, the student resorts to integral citations one after the other.

As Molinari and Mameli (2010), Walsh (2002) and Cullen (1998) confirmed, quality of the teacher talk is far more important than the quantity. … Gharbavi and Iravani (2014) have confirmed that teacher’ choice of words and way of treating students will affect their involvement. … Nystrand, Wu, Gamoran, Zeiser, and Long (2003) like Molinari and Mameli (2010) illustrated the importance of dialogic discourse in the classroom.

Once the student is informed of the importance of variety in the text and notified to make reading the RA a more enjoyable task to the reader, the student makes some changes in the second draft:

Research suggest that quality of the teacher talk is far more important than the quantity (Cullen, 1998; Molinari & Mameli, 2010; Walsh, 2002).… Gharbavi and Iravani (2014) have confirmed that teacher’ choice of words and way of treating students will affect their involvement. … Nystrand, Wu, Gamoran, Zeiser, and Long (2003) illustrate the importance of dialogic discourse in the classroom; similar findings are also reported (Molinari & Mameli, 2010).

Direct Quotation Overuse: Using direct quotations one after the other characterized some of the earlier drafts. Apart from making the text boring, including too many quotations came at the cost of losing their authorial voice, a feature Flowerdew (2001) observed in non-native published RAs. When receiving comments on this flaw, the students mentioned that there is little they can have of their own, “Who are we, to make a claim?” one student noted. A large portion of the in-text citations in the coming drafts were in the form of summaries and paraphrases, rather than mere quotations.

Lack of variety: Lack of variety in the text featured some drafts. In the following 179-word sample, the phrase “according to” is repeated 4 times.

Almost everyone thinks of plagiarism as copying another's work or using someone else's authentic ideas. But terms like "copying" and "using" can relegate the importance of the offense. According to the Merriam-Webster (2014) to "plagiarize" means to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one's own, to use (another's production) without crediting the source, to commit literary theft, and to present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source. According to above definitions, one can consider plagiarism an act of fraud since it involves stealing someone else's work. On the contrary, some regular folk believe that it is impossible to steal words since they are totally unfamiliar with the concept of plagiarism. According to Hyland (2001) thanks to new technologies, students have direct access to interminable sources of information, which allows them to integrate them and fabricate an article without any citations. In order to clarify the concept of plagiarism, let us see which actions fall under the category of plagiarism. According to Yamada (2003), the following are considered plagiarism:

The same Student’s revision of the text resulted in the following:

According to the Merriam-Webster (2014) to "plagiarize" means to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one's own, to use (another's production) without crediting the source, to commit literary theft, and to present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source. Based upon this definition, one can consider plagiarism an act of fraud since it involves stealing someone else's work. On the contrary, some regular folk believe that it is impossible to steal words since they are totally unfamiliar with the concept of plagiarism. Hyland (2001) mentions thank to new technologies, students have direct access to interminable sources of information which allows them to integrate them and fabricate an article without any citations. In order to clarify the concept of plagiarism, let us see which actions fall under the category of plagiarism. Yamada (2003) believes the following are considered plagiarism:

Over-referencing: Over referencing to a particular source was detected in some students’ samples. Peacock (2011) was cited three times in a short paragraph.

The 10 previously discussed research articles were “randomly” opted out of the 5 mentioned well-esteemed journals in applied linguistics area (Li & Ge, 2009; Peacock, 2011) by assigning each article a “number” and conducting the “randomization” (Peacock, 2011). As discussed earlier, all 5 journals, which had been previously upheld by an applied linguist, Peacock (2011), Weber and Campbell (2003), Jung (2004) and Egbert (2007), possessed high impact factors (JCR, 2017) which certified their respect and academic position in applied linguistics discipline.

Being advised to revise the text with respect to over referencing, the student decided to remove the two parenthetical citations altogether and leave the integral citation intact.

Method:

Vague and incomplete: The method sections were mainly vague and incomplete:

Three Iranian experienced teachers are the participants. I chose non-participant observation. The design of my study is qualitative.

It was explained that the reader needs the details in this section in order to appraise the validity and reliability of the instruments. Therefore, any missing information could lead the reader to misinterpret the findings! As such, a well-prepared method allows for a full appreciation and a complete replication of the study. Relevant details on methodology could be discerned in the final drafts.

Three Iranian experienced non-native teachers at elementary level took part in the study. Beginning levels teacher are more responsible for encouraging the learners to engage than higher levels. When the students pass to advanced classes, they will feel more responsible for their own learning and participation. Non-participant observation is made. It is important to investigate teacher and students interaction. Because conversation analysis is used to understand the discourses that teachers use the design is qualitative.

Unclear table headings: The tables carried unclear titles and were not mentioned in the body of the paper; there were few figures, if any. When reporting the results, they just included the table with no elaboration on the content.

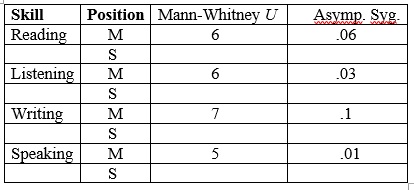

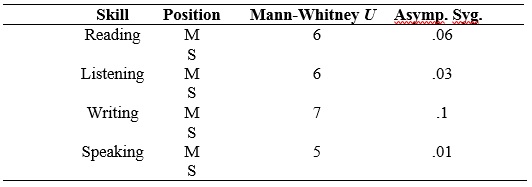

Table 6: Results of the Mann Whitney Test

This student was asked to revise the table for a self-contained title, and APA format. Adding notes to the table to clarify the acronyms was also advised. In later drafts, one could observe informative and readily comprehensible headings for tables prefaced with texts and enriched with proper figures, when appropriate. The revised version of the very table comes below.

M: Managers, S: Staff

Revised Table 6: Results of the Mann Whitney Test for Differences between Managers' and Staff's Perceptions of Target Profession-Oriented English Needs

Highlighting the main findings was noticeable in the results sections of the following drafts. One could trace instances of explanatory text merged with mere description in the discussion section, suggesting that the moves in the discussion were properly assimilated and absorbed. Comparable outcomes are reported in Kelly-Laubscher et al. (2017) where “By the final hand-in there was a shift towards more explanatory text” (p. 9).

Results

Results and discussion distinction: A problem traced in the Results and Discussion sections was that the students could not figure out the distinctions between the two. They supposed both were mere reports of the findings. The discussion of a student project follows.

As Table 1 illustrates, in the monolinguals’ compositions, elaborative (25.35%) and contrastive (25%) markers formed the largest percentage of usage, followed by reason (19.10%), and inferential (17.67%) markers. Conclusive (12.5%) and exemplification (00.35%) markers had the least occurrences, respectively.

To help students write discussions that were not mere reports of results, the researcher built upon Table 5, Distributions of moves and steps across empirical law RA sections (Tessuto, 2015) and the “Data Commentary” (Swales & Feak, 2012). I reintroduced the moves and steps in the Discussion section, giving particular significance to the “reinforcing the results” move and the “interpreting/evaluating relevant (un)expected findings, and comparing findings with previous literature” steps. Moreover, the various and many tasks in “Data Commentary,” the term Swales and Feak (2012) use to refer to discussion, provided the students with extensive practice.

The revised draft of the discussion section follows:

The results chiefly highlight the impact of other factors than linguistic backgrounds on the participants’ DM type production. The similar pattern of the incidence of the first four DM types can be, as stated by Werlich (1982), traced back to different text types (in this study, the three persuasive, compare-and-contrast and cause-and-effect paragraphs) and even the nature of the task (Wei, 2011).

Strong claims: It is worth adding that a recurrent observed issue was making strong claims without offering a support all through their projects. Furthermore, the RA sections submitted were typically characterized with frequent use of terms carrying the inappropriate “force of the statement.”

The findings showed an urgent need for a total reconsideration of miscellaneous aspects of EAP courses in Business in light of future occupation of students.

Delineating the features of academic text, Hyland’s (1998) notions of hedges and boosters were introduced. Trends of more scholarly language use with the help of supporting claims from the literature and using the proper and milder assertions and more hedges could be discerned in the subsequent drafts. The revisited version of previously cited extract is given below.

Policy makers and materials developers are recommended to have a relook at the current EAP courses with an eye on the future occupation of the students.

Discussion:

Conclusion/Summary distinction: Yet another point deserving attention was the conclusion section. For some students, the conclusion was a mere summary of the findings. The two other moves of “Evaluating the study” and “Deductions from research” were missing from the projects. The conclusion of a project on the title “Elicitation and Recast Feedback Types on Learning Conditionals” is a synopsis of the outcome of the study.

The present study examined the effects of types of elicitation and recasts, and it can be stated that FFI helped the students select accurate forms of conditionals in the grammaticality judgment tests. The results indicated that the experimental group outperformed the control group who was deprived of that instruction in all conditional types.

In the revised version, the presence of the previously missing moves is noticeable.

The present study examined the differential effects of elicitation and recasts in FFI. The results indicated that the experimental group who were provided with FFI performed better than the control group, deprived of that instruction. This higher performance confirms findings of previous studies (Lyster, 2004). The results revealed that FFI was sufficient for students to improve their performance and CF was not an important factor. This result is in contrast with results of studies of Ammar and Spada (2006). In the present study, no attempt was made to control and equalize the frequency of different CF types provided to the groups.

Having characterized the drafts, in the next section the researcher aims at elaborating on students’ views with regard to GBI in the next section.

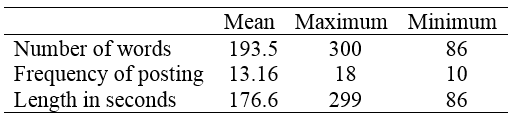

Voice Messages Analysis

The messages varied in terms of length and frequency, as shown in Table 4, with a maximum of 300 and a minimum of 86 words. Some posted longer voice messages (299 seconds) and more frequently (18 entries); while others kept it to a minimum (86 seconds and a mere minimum of 10 entries). This suggests that the task was more appealing to some; while it was not that attractive for others.

Table 4: Number of Words, Frequency, and Length of Postings

The following common themes emerging from the messages revealed to the researcher many interesting points, some surprising and some predictable.

Unclear assignments: For some students, the assigned out-of-class tasks of working with an article in the recommended journals and underscoring the moves were vague. They were not clear as to what they were exactly required to do and asked for some samples to guide them on how to do the task. I kept making them believe in their own works; yet, I referred them to the original samples we worked with in class. That said, the students very much appreciated working with the model extracts (Abstracts, Introduction, Method, Results, and Discussion).

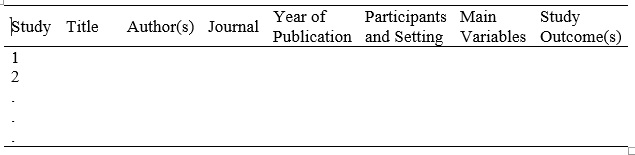

Literature review: Preparing the Literature Review section of their mini-projects, the major problem mentioned was how to choose and sort the selected sources. “I am stuck in the great bulks [sic] of my readings! Please help me out,” a student articulated her worries. Offering solutions, I explained how preparing a table, with precise summary of the studies could help. As shown in Table 5, the students were recommended to recapitulate their readings of each single source in a table, specifying the article title, the author(s), the target journal, etc. Such a table would assist students to fix an outline prior to writing the literature review section. Based on a similar table, the students could simply sort the studies and even devise a theme to establish a link among different pieces of researches included in their report.

Table 5: Template for Summarizing Sources in Tables

Collaborative work: A great tendency was observed on the part of the participants to work with peers. This way, they could witness the challenges of other peers in doing the tasks, and this made them feel better. Discovering via team work that other members, similarly, have difficulty doing the tasks makes the student feel less embarrassed. The opportunity offered by teamwork is accordingly encouraging. “I notice that my friends too have problems, like I do,” a student specifically pointed out.

Discussion

Building upon Swales’ (1990) IMRD framework and Situated Learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), the present study was conducted with the objective of reporting on a GBI methodology in an advanced writing course, describing students’ projects in light of moves analysis, and unveiling their views on the employed intervention. All in all, as echoed in students’ multiple drafts and their voice messages, there was an awareness of the acquired literacy practices. This is consistent with the observation made by Yang (2012) that “the majority of the learners perceived GBWI (Genre Based Writing Instruction) as beneficial to their writing” (p. 64). Additionally, the outcomes of Wang’s (2017) study conducted with Chinese learners who were “self-positioning,” followers of the instructed conventions, is comparatively in line with the current research findings. His participants, however, partly favored their own personal preferences, “self-direction,” despite the GB pedagogy they received. The mismatch, as Wang himself (2017) suggests, may tie with the complicated interactions between the pedagogy of genres and the learner’s variables. Kelly-Laubscher et al. (2017), too, reported “significant progress in terms of genre acquisition and development of genre awareness” (p. 1). With this study, too, the guidelines presented in the lecture sessions and later reinforced with group and individual works, and the multiple feedbacks on the drafts of the sections cumulatively formed students’ generic competence and raised their awareness. The comparison of the multiple drafts of the various sections of the RAs clearly supports the researcher’s claim, all this also evinced in students’ communicating their viewpoints with me.

Now, the article is very different to me. I read to discover the moves. I know where to look for what. This is amazing!!

Alternatively, another student writes:

In my other courses, moves really help me read. It takes shorter [sic] to read the article. I know which part is more important.

The greatest improvement, as discerned in their drafts and voice messages, was seen in the way students read the articles in light of the intervention, expecting what is to come in each section. The point that they read the RAs with the moves in mind was indicative of the fact that their “awareness” was promoted. Doing the in-class tasks, the students engaged in detailed discussions on the moves and steps for each RA section, all bringing about more expertise in analyzing the articles. Not surprisingly, parallel results are observed in lab reports produced by the African learners in the study by Kelly-Laubscher et al. (2017). In the present study, the consciousness-raising method of presentation actually created chances for collaborative learning and peer discussions. The new method of reading and appraising the articles, as students commented, augmented their understanding, as evidenced in the multiple drafts. This firmly pertains to Hirvela’s (2004) remark that helping learners become “writerly readers” promotes their consciousness to structure their writings. In the path of discovering meaning, the learners paid particular attention to previously going unnoticed fundamentals in RAs, figures and tables to name as instances.

Conclusion

This study had the goal of raising learner awareness of the structure of RA sections and enabled them to critically read and identify the moves, as well as to have the model in mind as they ultimately embarked on their own projects. Additionally, the researcher wished to examine learners’ perceptions. Through consciousness raising, the researcher helped students to notice the genre structure, the IMRD model, the way the RAs are structured, and the conventions practiced by scholars. Getting the big picture, the junior researchers could see how the moves were realized in the text and do their best to follow that pattern. All this was designed to help students become members of the discourse community (Hyland & Jing, 2017; Miller, 1984). It is hoped that such studies mitigate the difficulties that students face when writing a RA in a language which is not their own; in this sense, it can, according to Sheldon (2013), contribute to the "democratisation of knowledge across global academia" (p. 260). This conclusion is preliminary, though. In its small-scale investigation, the current study suffers from several limitations, such as the small sample size of twelve students. A more rigorous methodology could be adopted. The lack of a control group against which to compare the intervention group’s performance can be mentioned as another limitation. Given that the students were at the pre-research stage, they had no immediate need for the instruction and no solid research to write up. It is, therefore, not surprising that some students reported dissatisfaction. “I do not quite understand why we must follow rules. I like to write my own way,” complained a student. Wang (2017) reports similar learner behavior, what he calls “self-direction.” The research presented represents only one perspective, that of students, whilst other agents are teachers, one of the principal stakeholders, including whose perspectives on GBI in future research will probably lead to conclusions that are more rigorous.

I wish to end the article with a student quotation that suggests the significance of this study.

After reading parts of Swale's Genre Analysis, I just realized it lies at the very heart of almost every piece of writing, and before embarking on writing a research article in any discipline, one must familiarize themselves with the complexities of the RA genre. I just wanted to share my excitement with you.

Acknowledgement:

I'd like to thank the editor and the two anonymous reviewers' valuable feedback on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

References

Bhatia, V. K. (1993). Analyzing genre: Language use in professional settings. Longman.

Bhatia, V. K., Flowerdew, J., & Jones, R. J. (2008). Approaches to discourse analysis. In V. K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew & R. H. Jones (Eds.), Advances in discourse studies (pp. 1-17). Routledge.

Brett, P. (1994). A genre analysis of the results section of sociology articles. English for Special Purposes, 13(1), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(94)90024-8

Cheng, A. (2008). Analyzing genre exemplars in preparation for writing: The case of an L2 graduate student in the ESP genre-based instructional framework of academic literacy. Applied Linguistics, 29(1), 50-71. http://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm021

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. https://www.jstor.org/stable/356600

Flowerdew, J. (2001). Attitudes of journal editors to nonnative speaker contributions. TESOL Quarterly, 35(1), 121-150. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587862

Flowerdew, J. (2013). Discourse in English language education. Routledge.

Han, J., & Hiver, P. (2018). Genre-based L2 writing instruction and writing-speciï¬c psychological factors: The dynamics of change. Journal of Second Language Writing, 40, 44-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.03.001

Hashemi, M. R., & Babaii, E. (2013). Mixed methods research: Toward new research designs in applied linguistics. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 828-852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12049.x

Hashemi, M. R., & Gohari Moghaddam, I. (2016). A mixed methods genre analysis of the discussion section of MMR articles in Applied linguistics. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(2), 1-19. 242-260. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1558689816674626

Herrington, J. & Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3). 23-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02319856

Hirvela, A. (2004). Connecting reading and writing in second language writing instruction. The University of Michigan Press.

Holmes, R. 1997. Genre analysis, and the social sciences: An investigation of the structure of research article discussion sections in three disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 16(4) 321-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00038-5

Hyland, K. (1998). Boosting, hedging and the negotiation of academic knowledge. TEXT, 18(3), 349-382. http://hdl.handle.net/10722/130127

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K., & Jing, F. (2017). Is academic writing becoming more informal? English for Speciï¬c Purposes, 45, 40-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2016.09.001

Hyon, S. (1996). Genre in three traditions: Implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly, 30(4), 693–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587930

Johns, A. M. (2011). The future of genre in L2 writing: Fundamental, but contested, instructional decisions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2010.12.003

Kelly-Laubscher, R., Muna, N., & Van der Merwe, M. (2017). Using the research article as a model for teaching laboratory report writing provides opportunities for development of genre awareness and adoption of new literacy practices. English for Specific Purposes, 48, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2017.05.002

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lenkaitis, C. A. & English, B. (2017). Technology and telenovelas: Incorporating culture and group work in the L2 classroom. MEXTESOL Journal, 41(3), 1-20. www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=2514

Martin, J. R. (1993). A contextual theory of language. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), The powers of literacy: A genre approach to teaching writing (pp. 116–136). University of Pittsburgh Press.

Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638409383686

Moghaddam, A. (2006). Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues in Educational Research, 16(1), 52-66. http://www.iier.org.au/iier16/moghaddam.html

Peacock, M. (2011). The structure of the methods section in research articles across eight disciplines. Asian ESP Journal, 7(2), 99-124. http://asian-esp-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/AESP-Volume7-Issue2-April-2011.pdf

Shah, J., Shah, A. & Pietrobon, R. (2009). Scientific writing of novice researchers: What difficulties and encouragements do they encounter? Academic Medicine, 84(4), 511-516. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a8c3c

Sheldon, E. (2013). The research article: A rhetorical and functional comparison of texts created by native and non-native English writers and native Spanish writers. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. University of New South Wales. https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/252601168

Staples, S.& Reppen, R. (2016). Understanding ï¬rst-year L2 writing: A lexico-grammatical analysis across L1s, genres, and language ratings. Journal of Second Language Writing, 32, 17-35. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1060374316300066

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (2012). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills (3rd ed.) University of Michigan Press.

Swales, J. M., & Lindemann, S. (2002). Teaching the literature review to international graduate students. In A. M. Johns (Ed.), Genre in the classroom: Multiple perspectives (pp.105-120). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Swales, J., & Najjar, H. (1987). The writing of research article introductions. Journal of Written Communication, 4(2), 175-191. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0741088387004002004

Tardy, C. M. (2016). Beyond convention: Genre innovation in academic writing. The University of Michigan Press.

Tessuto, G. (2015). Generic structure and rhetorical moves in English-language empirical law research articles: Sites of interdisciplinary and interdiscursive cross-over. English for Speciï¬c Purposes 37, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2014.06.002

Wang, W. (2017). Learner characteristics in an EAP thesis-writing class: Looking into students’ responses to genre-based instruction and pedagogical tasks. English for Specific Purposes, 47, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2017.04.002

Yang, W. (2012). A study of students’ perceptions and attitudes towards genre-based ESP writing instruction. Asian ESP Journal, 8(3), 49-73. http://asian-esp-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/AESP-Volume-8-Issue-3-October-2012.pdf

Zhang, W., & Cheung, Y. L. (2017). Understanding ENGAGEMENT resources in constructing voice in research articles in the fields of computer networks and communications and second language writing. Asian ESP Journal, 13(2), 72-99. https://www.elejournals.com/1615/2017/asian-esp-journal/asian-esp-journal-volume-13-issue-2-december-2017

[1] The bibliographic information of all the samples appears in Appendix A.