Introduction

Over the past decades, research on teacher development and learning has produced important evidence concerning psychological, cognitive, and social characteristics of teachers and their professional engagement, placing growing emphasis on the socio-ecological aspects of teaching with a particular focus on the concept of teacher identity (see Pennington & Richards, 2016). Given the substantial theoretical and empirical expansions in teacher identity studies, it is no surprise that this area of research has attracted considerable attention during the past two decades (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009; Clarke, 2008; Johnson, 2003; Kayi-Aydar, 2019; Leigh, 2019; ; Macías Villegas et al., 2020; Miller, 2009; Mora et al., 2016; Nguyen, 2016; Rodrigues & Mogarro, 2019; Simon-Maeda, 2004; Tsui, 2007; Varghese et al., 2005).

The importance associated with the concept of teacher identity (De Costa & Norton, 2017; Kayi-Aydar, 2015; Varghese et al., 2016) has motivated researchers— mostly in mainstream education—to devise measures to probe and quantify the construct. As recorded in the teacher education literature, several inventories have been developed, validated, or adapted to elicit quantitative data on teacher professional identity (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Beijaard et al., 2000; Canrinus et al., 2012; Cheung, 2008; Hasegawa & Kudomi, 2006; Starr et al., 2006). Despite the fact that a number of teacher professional identity questionnaires are now available in different educational fields, one can hardly find a standardized EFL-specific teacher professional identity inventory; thus, the need for a specific questionnaire on EFL teacher professional identity can be justified.

Definitional varieties exist in the related literature with respect to conceptualizing EFL teacher professional identity (Rodrigues & Mogarro, 2019). As Beijaard et al. (2004,) assert, the teachers’ professional identity include both “core” and “peripheral” components (p. 122). According to Beijaard et al. (2004), a teacher’s professional identity consists of “sub-identities” that

… more or less harmonize. The notion of sub-identities relates to teachers’ different contexts and relationships. Some of these sub-identities may be broadly linked and can be seen as the core of teachers’ professional identity, while others may be more peripheral. (p. 122)

According to Sinha and Hanuscin (2017), the core and peripheral components of teacher identity are likely to be mediated by a self–other relationship, meaning that identity is formed on the basis of social roles identifying a person’s position in a group and role identities as the individual’s self-image. Although identity can be influenced by temporal and spatial dimensions of a person’s individual and social experiences, teachers may well be able to capture the common core features of their social and role identities at a particular point in time, helping researchers delineate language teachers’ professional identity by making use of appropriate scales.

Adopting this view for the purpose of the present study, we assumed that professional identity of language teachers was a coherent and complex whole (see Henry, 2016) that is made up of core components and flexible peripheral characteristics. The core components are the ones that shape the essential, distinguishing, and common features of EFL teacher professional identity. The changing characteristics are the ecological, context-sensitive, individual-dependent features that fluidize identity in a way that it is induced through the teacher’s self-reflection, interpretation, and adoption of multiple roles over time. As Henry (2016) argues, teacher identity as a complex dynamic system does not undergo random transformations; rather, it can be patterned on the basis of its “stable dynamical” behavior at different points in time, revealing “predictable consistency” through shifts that occur between the major identity components or “fixed-point attractors in an iterative process” (p. 301). In a developmental process of identity formation, it would be helpful to objectively examine cross-sections of this complex system for the purpose of patterning and recording how the core components and main attractors influence identity formation and transformation.

The present study utilized a sequential mixed methods approach to explore the components of EFL teachers’ professional identity for the purpose of developing and standardizing a questionnaire. According to Hashemi and Babaii (2013), sequential exploratory designs are utilized for “evaluating and/or developing measurement instruments like questionnaires, tests, rating scales, inventories …and/or validating measurement instruments” (p. 840). As Creswell and Plano Clark (2011) elaborate on the term, the exploratory design begins with the collection and analysis of qualitative data. The quantitative data – informed by the analysis of the qualitative data - are also collected and analyzed to test or generalize the initial findings.

In this manuscript, the procedures followed for qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis have been addressed. As will be explained thoroughly, in the qualitative phase of the study, data were gleaned from 24 informants. Findings of the qualitative analysis provided the input required for the quantitative phase of this sequential exploratory study. Hence, the first version of the inventory was developed through exploratory factor analysis and validated through structural equation modeling. The manuscript elaborates on the qualitative and quantitative findings of the study. The results are then situated in the related literature. The manuscript ends by discussing the implications of the study.

Teacher Identity

As a transdisciplinary concept (De Costa & Norton, 2017), identity has attracted the attention of philosophers, scholars, and researchers from various disciplines for a long time. Besides its philosophical underpinnings, the concept of identity has been influenced by various approaches and schools in the social and human sciences.

Considering the individual and socio-cultural perspectives, identity is “the style of one’s individuality which coincides with the sameness and continuity of one’s meaning for others in the immediate community” (Erikson, 1968, p. 50). In a non-essentialist sense, the social constructivist view places a particular focus on social interactions and mediation in identity development. The Vygotskian sociocultural approach to identity treats identity development as “a process of transformation of individual functioning as various forms of social practice become internalized by individuals” (Wertsch, 1991, as cited in Penuel & Wertsch, 1995, p. 84). Calling to mind the Latin origin of the term, identity is “what makes you similar to yourself and different from others” (Deschamps & Devos, 1998, p. 3). Drawing upon this type of sameness and difference, Doise (1998) holds that identity can be understood as a social manifestation, an organizing principle of individual positioning in a field of symbolic relationships between an individual and the groups he or she interacts with.

Within the EFL context, despite the range and diversity of studies on teacher identity, the concept remains fuzzy. In fact, most of the studies in this area have attempted to explore characteristics that correspond to teacher identity rather than present a comprehensive definition of it (Han, 2017). This postulation has its origin in the idea of identity being a “relational phenomenon” not “a fixed attribute of a person” (Beijaard et al., 2004, p. 108). According to Beijaard et al. (2004), teacher professional identity develops interpretively and intersubjectively within a dynamic, continuous process of exploring the self and the other regarding the personal, professional, and social dimensions of one’s being. Along similar lines, Barkhuizen (2016) argues that identities are derived from cognitive, sociohistorical, and ideological origins. As Barkhuizen (2016) states, “language teacher identities are multiple, and they change, short-term and over time—discursively in social interaction with teacher educators, learners, other teachers, administrators, and the broader community, and in material interaction with spaces, places, and objects in classrooms and institutions” (p. 659). This view has been similarly conceptualized through a “relational being” aspect of identity defining the self in relation to others (Morgan, 2017). Morgan (2017) holds that identity is a multifaceted phenomenon that alters within a complex system of “relational dynamics” depending upon “context, role, experience, and perspective of each individual in the relationship”( p. 43) From a socio-psychological perspective, the teacher’s roles in different contexts and his or her “cognition,” “emotion,” and “action” form the teacher’s identity as a whole that may comprise his or her gender identity, learner identity, teacher identity, etc. (Han, 2017).

Teacher Professional Identity

Defined by Dent and Whitehead (2002), the professional is “someone trusted and respected, an individual given class status, autonomy, social elevation, in return for safeguarding our wellbeing and applying their professional judgment on the basis of a benign moral or cultural code” (p. 1). The professional develops a self-image within an institutionalized culture in relation to others (i.e., colleagues, customers, family members, members of the society, etc.) based on which his or her identity can be developed and negotiated. Drawing on Schein (1978), Ibarra (1999) defines professional identity as the “constellation of attributes, beliefs, values, motives, and experiences in terms of which people define themselves in a professional role” (pp. 764–765).The development of teacher professional identity, thus, involves an enduring, formative, transformative, and dynamic process of making sense of and interpreting or reinterpreting an individual’s own values and experiences through reflexive and expressive negotiation of the teacher’s subjectivity which is prone to change as a result of personal, affective, social, and cognitive factors (Flores & Day, 2006; Ibarra, 1999; Miller, 2009; O’Connor, 2008; Tsui, 2007).

Research in the EFL context has explored EFL teacher professional identity in terms of its conceptualization, development, and negotiation. However, due to the complicated, dynamic, and fluid nature of the concept of identity, most of the studies conducted in this area of research address formation and negotiation of teacher professional identity. The following is a selective review of such studies.

For example, Bukor (2015) explored the impact of personal and professional experiences on the development of language teacher identity of three language teachers. The results indicated that teacher professional identity is deeply rooted in the individual’s personal biography. Similarly, utilizing a retrospective life-history research methodology, Mora et al. (2016) probed “the interrelationship between language teachers’ professional identities and their degree of investment in academic and professional activities” (p. 182). The findings of the study indicated that locally educated teachers built a strong identity due to a number of reasons, including stable family context and smooth transitions in their lives. In another study, Nguyen (2016) explored the way English teachers have aimed at developing practice and identity in the local context of Vietnam. Analysis of the interview data showed that upon entering their teaching career, Vietnamese teachers found self-learning and learning from their colleagues insufficient for professional development and their professional development expanded to pedagogical practices and discourses in other communities as well as engagement in multiple communities.

In a Sudanese case study of EFL pre-service teachers, Elsheikh (2016) focused on the construction of teacher professional identity and its relationship with the teaching practice and sociopolitical context. Qualitative analysis of observation notes and interview transcripts revealed that the participants’ discursive constructions and experiences of teaching influenced how they considered themselves as future teachers and professionals. In a four-year qualitative study, WerbiÅ„ska (2016) investigated language teacher professional identity by means of analyzing discontinuities (interruptions) such as encounters with difference, unfamiliarity, or disagreement. The findings demonstrated that teacher professional identity played a key role in teacher education programs, as it provided the grounds for teacher candidates’ meaning and decision making, and it tended to increase their awareness and development of more complex perceptions of language teaching practice. In order to conceptualize EFL teacher professional identity, Han (2017) utilized interviews, descriptive questionnaires, word and visual metaphors, and classroom observations. Several identities revealed as a result of the study include national identity, English teacher identity, teacher identity, learner identity, gender identity, and public servant identity. Adopting a critical viewpoint, Miller et al. (2017) argued for fostering the language teachers’ “reflective” and “action-oriented” identity practices in light of their roles as ethical agents. Drawing on narrative inquiry and positioning theory, Leigh (2019) explored the professional identities of eight EFL teachers in China. Analysis of the interview data revealed that teachers tend to draw on similar positions to describe themselves and others. During the process of identity construction and negotiation, these identity constructions provide insights into teachers’ interpretations of who they are in a foreign place, as well as into elements of Chinese context influencing the teachers’ narrated experience.

Recent research into negotiation of language teacher professional identity suggests that, being embedded in the stories of teachers (Barkhuizen, 2017), identities are multiple, dynamic, and transitory (Barkhuizen, 2016). In this sense, negotiating differences is an important aspect of institutionalized identity realization in a socio-professional context (Tsui, 2007). As the above mentioned empirical and conceptual evidence show, most of the studies on teacher identity address the issue qualitatively—further adding to the complexity and fluidity of the concept. Thus, the motive behind the present study was to complement the qualitative strand with a quantitative module to provide a broader picture of the concept of language teacher professional identity. The present study addressed the following research question: What are the core components of EFL teacher professional identity?

Method

As noted earlier, to develop and validate an EFL teacher identity scale, we utilized a sequential exploratory mixed methods approach as an appropriate method for developing quantitative instruments (Hashemi & Babaii, 2013). The study was conducted in two consecutive phases. First, in the early questionnaire development stage, qualitative data were collected and analyzed. This phase informed the second phase in which the quantitative strand was implemented for the purpose of validating the instrument.

The Qualitative Phase

Sampling and Participants.

A sequential multilevel sampling strategy was used for the purpose of the study. As for the qualitative phase, a purposive sample of twenty-four informants participated in the study. The sample included seven experts (Ph.D. holders in applied linguistics), six teacher educators, six experienced teachers, and five advanced level EFL students. The experts were university instructors who specialized in teacher education. The teacher educators were selected on the basis of their professional experience in teacher education and training, classroom observation, and teacher supervision. The teachers who participated in the study had more than ten years of teaching experience. Finally, the students who took part in the qualitative phase of the study were all advanced level students who had participated in language courses for at least three years.

Qualitative Data Collection.

Interviews were utilized to gather data in the qualitative phase. Based on extensive literature reviews, two lists of questions were prepared. The first list consisted of 18 questions and aimed at exploring EFL teacher professional identity from the point of view of experts, teacher educators, and teachers by eliciting the interviewees’ opinion on various aspects of the issue. These aspects were extracted from the literature and included professional EFL teachers in relation to themselves as individuals (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Cheung, 2008; Hasegawa & Kudomi, 2006) and as teachers (Beijaard et al., 2000; Cheung, 2008); in relation to their students (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Beijaard et al., 2000; Cheung, 2008; Hasegawa & Kudomi, 2006); in relation to their colleagues (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Cheung, 2008; Starr et al., 2006); in relation to their students’ parents (Cheung, 2008); in relation to their workplace conditions (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Cheung, 2008); with regards to the community of practice (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Starr et al., 2006); in relation to the material they are teaching (Tomlinson, 2001), and in relation to the wider society in which they live (Sutherland et al., 2010). Also, three of the interview questions addressed the likely relationship between teacher professional identity, experience, and expertise. The second list included six questions and was developed to elicit the EFL students’ opinions about their English teachers’ professional features with regards to themselves, their colleagues, their students, their students’ parents, the supervisors and managers, the community of practice, the material they are teaching, and the wider society in which teachers live.

To ensure credibility of the questions, two experienced and active researchers in the field of language teacher education examined the lists with regards to the content and wording of the questions. The results gained from the expert judgment phase guided us through the process of modifying and revising the interview questions and, consequently, led to the inclusion of three further questions on conceptualizations of identity, teacher identity, and teacher professional identity.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants. Of the 24 interviews that were conducted, 17 were undertaken face-to-face and the remaining were administered via email or internet chats. Each interview took about 50 minutes. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewees were fully briefed on the purpose and conduct of the interview. In doing so, the key terms used in the questions were defined to them. Upon their preference, all the interviews were conducted in English. To prevent any kind of data loss, we used three devices to record each interview (i.e., a sound recorder, a smart phone, and a tablet—using a sound recording application). Each interviewee’s consent was obtained before audio recording the interview.

Qualitative Data Analysis.

All the interview transcripts were analyzed closely in terms of content through qualitative coding. More specifically, the interview audio files (total length: 866 minutes) were transcribed verbatim by one of the researchers. The interview transcripts together with the text of email interviews generated a corpus of 124,738 words. The text was color coded to identify each feature of teacher professional identity with regards to a specific stakeholder (i.e., teacher educator, teacher, student) using a separate color. This strategy facilitated the identification of the codes. Next, the themes were identified, categorized, and further examined to find “thematic connections within and among them” (Seidman, 2006, p. 119). As a result, a number of the themes were subsumed under the more general ones.

Appropriate measures were taken to ensure the credibility and dependability of this phase of the study. As Cohen et al. (2007) argue, one way to ensure validity of interviews is to check for face validity which was accomplished by judgment received from the two experts. Furthermore, utilizing “member checking” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 155), we asked three of the ELT experts, one of the teacher educators, two of the teachers, and one of the students to go through their interview transcripts and corroborate the themes that emerged from their interview transcripts. Triangulation of the data by sources (Cohen et al., 2007) was also employed to enhance the credibility of the study by applying a multilevel sampling strategy, thus collecting data from various groups. Moreover, theoretical credibility was taken into consideration as most of the themes emerged from the interview transcripts were reexamined in light of the relevant literature. Hence, upon facing an ambiguity in an utterance during the content analysis phase, we contacted the interviewee to ask for further clarification. To gain more exact results, the analysis was conducted again after an appropriate time interval (i.e., one month) elapsed. Finally, to ensure the inter-coder reliability, we asked a Ph.D. candidate of applied linguistics, working on her dissertation on teacher professionalism at the time of the present study, to code a portion of the data independently. The Cohen’s Kappa value was .71 which is relatively satisfactory.

The Quantitative Phase

Sampling and Participants.

Considering Nunnally’s (1978) recommendation regarding the participant–item ratio of 10–1, we distributed 915 questionnaires among EFL teachers. After several follow-ups, we received 750 questionnaires (i.e., a return rate of 81%). After three rounds of data cleaning, which included discarding the outliers detected through Mahalanobis distance, 605 questionnaires were considered as appropriately completed. The sample included both female and male teachers, 72.05% and 27.95%, respectively.

Quantitative data collection.

The analysis of the data in the qualitative phase led to the emergence of more than one hundred themes that would hypothetically characterize the probable features of EFL teacher professional identity, contributing to the development of the questionnaire items. In order to arrive at a clearer view of the construct, a tentative categorization of the items was developed that included components derived from analyzing the data gleaned from the qualitative phase.

The early version of the questionnaire was examined in a pilot study. In addition to collecting data from about 100 EFL teachers, we also sought expert judgment (from 3 active researchers in the field of applied linguistics) about the content of the inventory. Furthermore, a language teaching expert, a professional editor, and a news editor, all with near-native mastery of English, reviewed and revised the items in terms of the language used. Upon the initial analysis of the data, we made the required modifications. The modified version of the inventory consisted of 49 items. This version was used for statistical validation. To do so, it was distributed among EFL teachers in 44 language institutes in Tehran (context of the present study). Moreover, the online version of the same questionnaire, produced via Google documents, was shared with ELT-focused groups in academic websites such as LinkedIn and more general communities of teachers such as Yahoo groups, Google groups, and Telegram groups to be completed by Iranian EFL teachers.

Quantitative Data Analysis.

SPSS version 21 was used for principal component analysis (PCA) of the data. Prior to performing PCA, the suitability of the data for exploratory factor analysis was assessed and the assumptions were met. The rotation approach fitting the purpose of this study was Promax, categorized under oblique method of rotation. Next, to explore the validity of the construct, we used AMOS version 24 to analyze the data through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Results

The Qualitative Results

Content analysis of the transcribed interviews conducted with 24 informants led to the emergence of a number of core components constituting the construct, each with a number of themes underlying EFL teacher professional identity. The themes and components were considered to comprise a tentative construct and were retained considering their frequency or relevance to the field on the basis of expert judgment. What follows is a brief account of the general components, and the corresponding sample extracts are provided in Appendix 1.

- Having the ability to develop or select EFL materials

- Having error correction skills

- Having communication skills

- Being knowledgeable and up-to-date

- Having respectful behavior

- Being concerned about students’ ability and development

- Having management skills

- Having the ability to create a relaxed learning atmosphere

- Having the tendency to impart knowledge and experience

- Serving as an effective role model

The Quantitative Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis.

Prior to running the principal component analysis as an extraction method for exploratory factor analysis (Schmitt, 2011), the assumptions of PCA were met. Kaiser’s criterion was used to make a decision about the number of components to retain. Despite controversies concerning this criterion, Stevens (2009) argues that it can be more accurate than the scree plot if the Q/P ratio is < .3 where P is the number of variables and Q is the number of factors. As for the case of this study, this ratio is .2 which leads to prioritizing Kaiser’s criterion to the scree plot. Thus, the criterion for determining how many factors to extract was the eigenvalue greater than one (Stevens, 2009). Consequently, an initial analysis was run to obtain eigenvalues for each component in the data. Thirteen components had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of one and in combination explained 61.05% of the variance. Further examination of the data (i.e., the deletion of items having factor loadings less than .4) provided evidence to retain a total number of 42 items.

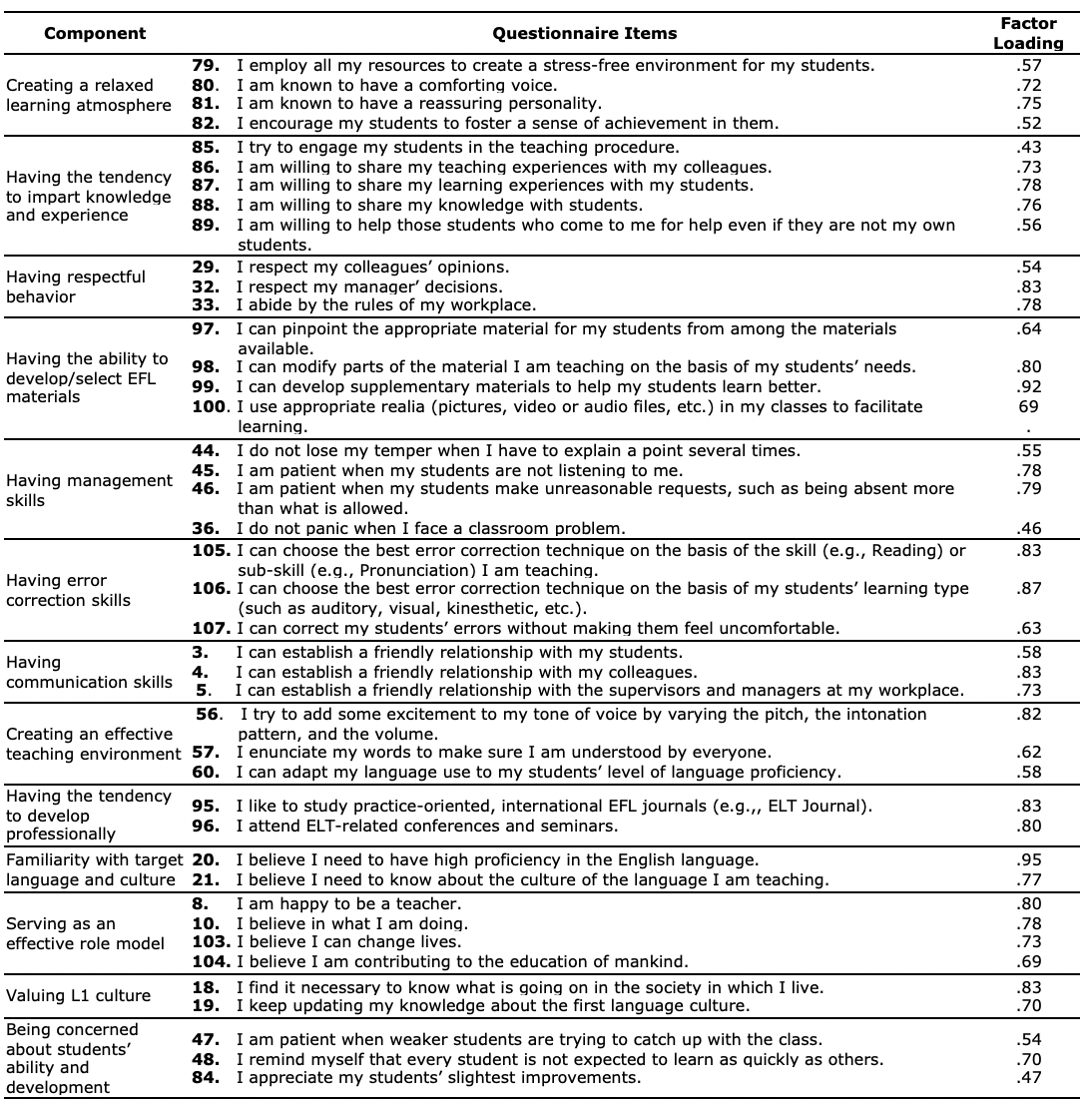

As stated earlier, the questionnaire items were written considering the 10 general themes and the underlying more specific themes that emerged from the interviews and finalized by expert judgment. Close scrutiny of the items and their corresponding factor loadings indicated a different clustering of the items though. Moreover, some themes were broken into sub-themes. Thus, some components were renamed in a post-hoc manner. We performed the factor renaming independently. The results were then compared to reach consensus regarding the choice of the most appropriate labels. Table 1 presents the renamed components, the corresponding items, and their factor loadings.

Table 1: The components, the corresponding items, and their factor loadings

Confirmatory factor analysis

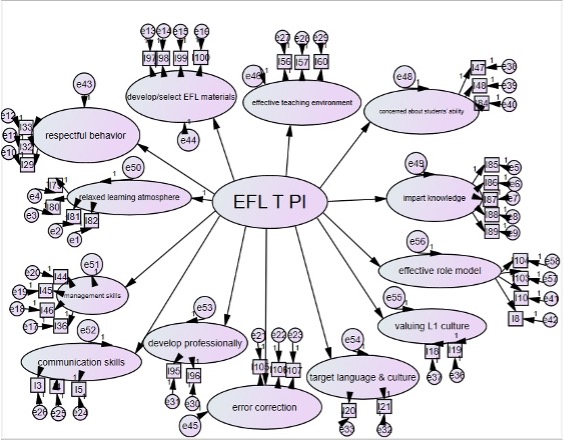

As Huck (2012) argues, in an SEM study, the measurement model is usually evaluated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA was, therefore, conducted on the 42 items (N = 605) to test the fit of the data to the model developed on the basis of the results of the exploratory factor analysis. Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the model proposed by the results of the exploratory factor analysis.

Figure 1. The model proposed by the results of the EFA with promax rotation and validated using CFA

The adequacy of the structure of the EFL teacher professional identity inventory was examined through conducting a confirmatory factor analysis for the sample described earlier. Various indices including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI) were calculated by means of AMOS version 24. According to Schumacker and Lomax (2010), the values of GFI, CFI, TLI, and NFI range from zero to one, where “zero indicates no fit” and “one indicates perfect fit”(p. 10). The value of the aforementioned indices in this study was .85, .83, .82, and .75 respectively, which indicates good fit. Moreover, according to Schumacker and Lomax (2010), the RMSEA range of .05 to .08 indicates a close fit. As for the case of the present study, the RMSEA was .05 which falls into the acceptable range. It thus can be claimed that the model fits the data.

Moreover, the factor loadings and correlations among factors were examined to establish convergent and discriminant validity. According to Huck (2012), convergent validity can be established when the factor loadings for a given latent variable are significantly high and discriminant validity is established when small factor loadings for other observed variables on that latent variable are noticed by the researcher. Close scrutiny of the correlation matrix indicated that convergent and divergent validities were also established in the study. For instance, whereas all the items loaded under component number twelve (i.e., valuing L1 culture) had considerable factor loadings, their factor loadings under the other components were too small or not conspicuous at all and therefore hidden from the matrix.

In order to establish the reliability of the questionnaire items, Cronbach’s coefficient of internal consistency was utilized. The Cronbach alpha coefficient calculated to check the internal consistency of this scale was .91 which is considered as an indication of appropriate internal consistency of the items (see Pallant, 2011).

Discussion

By utilizing a sequential mixed methods research approach, the present study attempted to develop and validate an EFL teacher professional identity questionnaire (see Appendix 2). Drawing on the relevant literature, the qualitative phase of the study utilized interviews in order to provide a detailed characterization of the construct and its components. The themes that emerged from the interviews were further investigated, and most of them corroborated in the quantitative phase so that the core features would be consolidated to form relevant categories through statistical analyses.

As attested in previous research (Beijaard et al., 2000; Cheung, 2008; Henry, 2016; Johnson, 2016; Trent, 2015; Yazan & Rudolph, 2018), the results of this study also point to the multi-dimensional and complex nature of teacher identity composed of individual, pedagogical, educational, and social dimensions. The items that correspond to the individual dimension address issues such as the teacher’s personality, patience, self-confidence, self-control, respectfulness, attitude toward language teaching, and voice. Regarding the pedagogical dimension, a number of the items check EFL teachers’ skill in correcting student errors, managing the classroom, adapting to the level of the students, developing and adapting EFL materials for classroom use, creating a stress-free atmosphere, engaging the students in the activities, and using realia. With respect to the educational dimension, the questionnaire includes items on the teachers’ tendency toward studying professional journals and attending ELT-related conferences, willingness to share his or her knowledge and experience with colleagues, and attitude toward professional development. Additionally, several items investigate the social and interactional aspects of EFL teacher professional identity (see Trent, 2015) by addressing the teachers’ attitude toward the social impact of language teaching and its value, his or her attention to social aspects of teaching, and his or her relationship with students and colleagues.

More specifically, a number of the components and themes found in the present study are in line with the general features of professional identity reported in the teacher education literature. For example, establishing effective communication was also reported in Abu-Alruz and Khasawneh (2013), Beijaard et al. (2000), Cheung (2008), and Starr et al. (2006). Additionally, familiarity with target language and culture was reported in Abu-Alruz and Khasawneh (2013), Starr et al. (2006), Beijaard et al. (2000), and Cheung (2008). The literature concerning teacher identity in general also provides support for themes such as being concerned about students’ ability and developmentand serving as a role model (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Cheung, 2008; Starr et al., 2006), and having the tendency to impart knowledge and experience (Abu-Alruz & Khasawneh, 2013; Starr et al., 2006).

However, there are a number of other professional features that remain exclusive to EFL teachers. The novel pedagogically oriented features that emerged in the present study include language error correction skills, the ability to develop or select EFL materials, and the ability to adapt one’s language to the level of the students. Considering the important role of culture with regard to EFL teacher identity, familiarity of the EFL teacher with the target language and culture and valuing L1 culture are important distinct features of an EFL teacher’s professional identity which become pertinent to recent developments regarding language teachers’ intercultural awareness (Brunsmeier, 2016). Finally, contributing to the teachers’ professional knowledge and language skills, command of the target language was also found to be a distinct feature of teacher professional identity.

Conclusion

The present study was an attempt to operationalize teacher professional identity in the EFL context. As mentioned earlier, the overall findings of the study point to major themes characterizing EFL teacher professional identity namely creating a relaxed learning atmosphere, having the tendency to impart knowledge and experience, having respectful behavior, having the ability to develop/select EFL materials, having management skills, having error correction skills, having communication skills, creating an effective teaching environment, having the tendency to develop professionally, familiarity with target language and culture, serving as an effective role model, valuing L1 culture, and being concerned about students’ ability and development. We consider this operationalization helpful since repeated use of this measure can contribute to revealing patterns in teacher identity development with respect to various independent variables (Avraamidou, 2014; Hanna et al., 2019).

Additionally, from a socio-cultural perspective, a closer look at teacher professional identity through a quantitative lens sheds light on several aspects of teacher professional agency at both individual and collective levels (Hökkä et al., 2017). The use of this quantitative instrument, alongside appropriate qualitative strategies in a mixed design, can yield insights into how language teacher professional identity can influence or be influenced by teacher strategies (Wolf & De Costa, 2017).

This study is significant in the sense that a standard scale for assessing EFL teachers’ professional identity can serve a crucial role in helping explore teachers’ professional identity and offer them insights as to adopting a more strategic approach to developing professionally in the field (Hanna et al., 2019). In addition, the study has implications for language teacher recruitment, education, supervision, and development. The questionnaire, if complemented by a qualitative component like an interview or a narrative (Barkhuizen, 2016, 2017), can be used by teacher trainers, supervisors, and mentors to have a clearer picture of the developmental process of novice or more experienced teachers’ professional identity—thus making it possible for them to tailor their training and feedback to the professional requirements of the teachers. Making use of an objective scale can help teachers fine-tune the interpretive subjective nature of their perceptions of teacher professional identity and achieve intersubjectivity with a balanced view, with respect to negotiating their professional identities.

The scale developed in the present study can help us capture a frame of teacher “identity performance” in a particular context assuming that identity involves “enacting and positioning of the self within specific contexts” (Pennington, 2015, p. 69). Although in a state of flux with regards to contexts and roles, teacher professional identity would have a set of core features that comprise the essence of it in relation to which peripheral elements of identity change and harmonize concomitant with individual, contextual, and socio-cultural factors (Beijaard et al., 2004). As the core and peripheral features combine in a particular EFL context, teacher professional identity becomes “a unique blend of individual teacher characteristics within the disciplinary knowledge, standards, and practices of the field” (Pennington, 2015, p. 78).

References

Abu-Alruz, J., & Khasawneh, S. (2013). Professional identity of faculty members at higher education institutions: A criterion for workplace success. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 18(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2013.847235

Avraamidou, L. (2014). Studying science teacher identity: Current insights and future research directions. Studies in Science Education, 50(2), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2014.937171

Barkhuizen, G. (2016). A short story approach to analyzing teacher (imagined) identities over time. TESOL Quarterly, 50(3), 655–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.311

Barkhuizen, G. (2017). Investigating language tutor social identities. Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12369

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

Beijaard, D., Verloop, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2000). Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a knowledge perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(7), 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00023-8

Brunsmeier, S. (2016). Primary teacher’s knowledge when initiating intercultural communicative competence. TESOL Quarterly, 51(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.327

Bukor, E. (2015). Exploring teacher identity from a holistic perspective: Reconstructing and reconnecting personal and professional selves. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.953818

Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2012). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: Exploring the relationship between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychological Education, 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0069-2

Cheung, H. Y. (2008). Measuring the professional identity of Hong Kong in-service teachers. Journal of In-service Education, 34(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580802003060

Clarke, M. (2008). Language teacher identities: Co-constructing discourse and community. Multilingual Matters.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. R. B. (2007). Research methods in education. Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE.

De Costa, P. I., & Norton, B. (2017). Introduction: Identity, transdisciplinarity, and the good language teacher. Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12368

Dent, M., & Whitehead, S. (2002). Introduction: Configuring the “new” professional. In M. Dent & S. Whitehead (Eds.), Managing professional identities: Knowledge, performativity and the “new” professional (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

Deschamps, J. C., & Devos, T. (1998). Regarding the relationship between social identity and personal identity. In S. Worchel, J. F. Morales, D. Paez, & J. C. Deschamps (Eds.), Social identity: International perspectives (pp. 1–12). SAGE.

Doise, W. (1998). Social representations in personal identity. In S. Worchel, F. Morales, D. Paez, & J. C. Deschamps (Eds.), Social identity: International perspectives (pp. 12–23). SAGE.

Elsheikh, A. (2016). Teacher education and the development of teacher identity. In J. Crandall, & M. Christison (Eds.), Teacher education and professional development in TESOL: Global perspectives (pp. 37–52). Routledge.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002

Han, I. (2017). Conceptualisation of English teachers’ professional identity and comprehension of its dynamics. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1206525

Hanna, F., Oostdam, R., Severiens, S. B., & Zijlstra, B. J. H. (2019). Domains of teacher identity: A review of quantitative measurement instruments. Educational Research Review, 27, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.01.003

Hasegawa, Y., & Kudomi, Y. (2006). Teachers’ professional identities and their occupational culture: Based on the findings of a comparative survey on teachers among five countries. Hototsubashi Journal of Social Studies, 38(1), 1–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43294496

Hashemi, M. R., & Babaii, E. (2013). Mixed methods research: Toward new research designs in applied linguistics. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 828–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12049.x

Henry, A. (2016). Conceptualizing teacher identity as a complex dynamic system: The inner dynamics of transformations during a practicum. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116655382

Hökkä, P., Vähäsantanen, K., & Mahlakaarto, S. (2017). Teacher educators’ collective professional agency and identity: Transforming marginality to strength. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.001

Huck, S. W. (2012). Reading statistics and research (6th ed.). Pearson.

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 764–791. https://doi.org/10.2307%2F2667055

Johnson, K. A. (2003). “Every experience is a moving force”: Identity and growth through mentoring. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(8), 787–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.06.003

Johnson, K. E. (2016). Language teacher education. In G. Hall (Ed.), Routledge handbook of English language teaching (pp. 121–134). Routledge.

Leigh, L. (2019). “Of course I have changed!”: A narrative inquiry of foreign teachers’ professional identities in Shenzhen, China. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102905

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). Multiple identities, negotiations, and agency across time and space: narrative inquiry of a foreign language teacher candidate. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 12(2), 137–160. https://10.1080/15427587.2015.1032076

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2019). Language teacher identity. Language Teaching, 52(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000223

Macías Villegas, D. M., Hernández Varona, W., & Gutiérrez Sánchez, A. G. (2020). Student teachers’ identity construction: A socially-constructed narrative in a second language teacher education program. Teaching and Teacher Education, 91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103055

Miller, E. R., Morgan, B., & Medina, A. L. (2017). Exploring language teacher identity work as ethical self-formation. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12371

Miller, J. (2009). Teacher identity. In A. E. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 172–81). Cambridge.

Mora, A., Trejo, P., & Roux, R. (2016). The complexities of being and becoming language teachers: Issues of identity and investment. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2015.1136318

Morgan, A. (2017). Cultivating critical reflection: Educators making sense and meaning of professional identity and relational dynamics in complex practice. Teaching Education, 28(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1219335

Nguyen, C. D. (2016). Creating spaces for constructing practice and identity: Innovations of teachers of English language to young learners in Vietnam. Research Papers in Education, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2015.1129644

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

O’Connor, K. E. (2008). “You choose to care”: Teachers, emotions and professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.008

Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. Allen & Unwin.

Pennington, M. C. (2015). Teacher identity in TESOL A Frames Perspective. In Y. L. Cheung, S. B. Said, & K. Park (Eds.), Advances and current trends in language teacher identity research (pp. 67–97). Routledge.

Pennington, M. C., & Richards, J. C. (2016). Teacher identity in language teaching: Integrating personal, contextual, and professional factors. RELC Journal, 47(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033688216631219

Penuel, W. R., & Wertsch, J. V. (1995). Vygotsky and identity formation: A sociocultural approach. Educational Psychologist, 30(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3002_5

Rodrigues, F., & Mogarro, M. J. (2019). Student teachers’ professional identity: A review of research contributions. Educational Research Review, 28, 100–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100286

Schein, E. H. (1978) Career Dynamics. Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Addison-Wesley.

Schmitt, T. A. (2011). Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0734282911406653

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press.

Simon-Maeda, A. (2004). The complex construction of professional identity: Female EFL educators in Japan speak out. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 404–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588347

Sinha, S., & Hanuscin, D. L. (2017). Development of teacher leadership identity: A multiple case study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.004

Starr, S., Haley, H-L., Mazor, K. M., Ferguson, W., Philbin, M., & Quirk, M. (2006). Initial testing of an instrument to measure teacher identity in physicians. Teaching and learning in Medicine: An international journal, 18(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1802_5

Stevens, J. P. (2009). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Routledge.

Sutherland, L., Howard, S., & Markauskaite, L. (2010). Professional identity creation: Examining the development of beginning preservice teachers’ understanding of their work as teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.006

Tomlinson, B. (2001). Materials development. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 66–71). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667206.010

Trent, J. (2015). Towards a multifaceted, multidimensional framework for understanding teacher identity. In Y. L. Cheung, S. B. Said, & P. Kwanghyun (Eds.), Advances and current trends in language teacher identity research (pp. 125–154). Routledge

Tsui, A. B. M. (2007). Complexities of identity formation: A narrative inquiry of an EFL teacher. TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 657–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00098.x

Varghese, M. M., Motha, S., Trent, J., Park, G., & Reeves, J.. (2016). Language teacher identity in multilingual settings. TESOL Quarterly, 49(1), 219–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.221

WerbiÅ„ska, D. (2016). Language teacher professional identity: Focus on discontinuities from the perspective of teacher affiliation, attachment and autonomy. In C. Gkonou, , D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 135–157). Springer.

Wolf, D., & De Costa, P. I. (2017). Expanding the language teacher identity landscape: An investigation of the emotions and strategies of a NNEST. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12370

Yazan, B., & Rudolph, N. (Eds.). (2018). Criticality, teacher identity and (in)equity in English language teaching: Issues and implications.Springer.