Introduction

Teacher preparation programs have long integrated practical experiences. Most programs include student teaching practicums, but beyond and even within student teaching experiences, the nature of practical experiences ranges (Richards & Crookes, 1988). There is emerging use of coaching with pre-service teachers; however, this professional development model is more common in professional development of in-practice teachers. It is a particularly interesting model to be explored in teacher education as it stands apart from many other pre-practice experiences (e.g., coursework, fieldwork, practicum) because it is non-evaluative and, in some cases, asset-based in nature.

In the United States (U.S.), English learners are those students whose English language proficiency is still developing and who are protected by laws and policies that entitle them to instruction that makes content comprehensible and develops academic language. Often, English learners are learning grade-level content in English. Consequently, in U.S. schools, there has been an increased use of coaching to develop in-practice teachers’ abilities to work with English learners. To address the impact of limited opportunities for pre-service teachers to learn in classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic, “the New York State Education Department…suggested that school districts and local teacher support organizations provide additional support such as mentoring, coaching, and co-teaching to their first-year teachers” (Cho & Clark-Gareca, 2020, p. 4). In Massachusetts, a state in the northeast of the United States, the local TESOL International-affiliate, Massachusetts Association of Speakers of Other Languages (MATSOL), has formed a new group to provide a networking space for instructional coaches. Instructional coaching has the potential to be a powerful professional development model for both pre-service teachers and their coaches in the field of ELT which has a great diversity regarding learners and requires a continuous modification of its curriculum and ways of instruction. Yet there is little research on coaching for pre-service teachers in the field.

This exploratory study examines the case of one coaching partnership that existed in a teacher preparation program in the state of Massachusetts in the U.S. The partnership was between an ELT faculty member and a pre-service teacher pursuing a Massachusetts educator’s license to teach English as a Second Language (ESL) to English learners in preschool through middle school grades. The pre-service teacher was a graduate assistant for the Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Department, and in that role she was responsible for delivering a course to prepare adult school paraprofessionals to pass the Communication and Literacy Skills Massachusetts Test for Educator Licensure (MTEL), a test which is required for all teachers in Massachusetts and which is often an entry requirement for educator preparation programs in Massachusetts. Paraprofessionals are educators who are not required to hold a teaching license. The course that the pre-service ESL teacher in this study taught was specifically designed to prepare multilingual paraprofessionals to pass this test so that they could go on to become teachers, although the course was not restricted to multilingual participants. The specific goals of this case study were 1) to better understand how a coaching partnership could impact the teaching practice of a pre-service ESL teacher and 2) to learn about the process of forming a coaching partnership between an ELT faculty member new to the coaching model and a pre-service teacher in the field of ESL.

Literature Review

Research on coaching and peer-coaching points to a range of models and approaches. One such model is instructional coaching. According to Knight (2007), in this model the goal is to improve classroom instruction through a collaborative partnership between teachers and coaches, who share instructional expertise. Knight outlines seven principles for creating teacher-coach partnerships: equality, choice, voice, dialogue, reflection, praxis, and reciprocity. Analyzing observation data together focuses teacher-coach dialogue on student learning and a “bottom-up” approach to teacher growth. Although the coach shares ideas, he or she remains open to the teacher’s point of view and provides positive and constructive feedback that is direct, specific and non-attributive (Knight, 2007).

Scholarship on ELT teacher education and professional development points to the importance of key elements of instructional coaching, such as (1) “goal-focused interactions in actual teaching practices in which expert others [experienced educators] provide guidance and feedback” (Lengeling & Wilson, 2017, p. 3), (2) a focus on the teacher’s own classroom (Anderson, 2018; Brancard & Quinnwilliams, 2012), (3) reflection (Clemente, 2004; Wilcox, 2001) and (4) trust (Chamberlin, 2000). A few studies have mentioned coaching as a means of ensuring that teachers implement a focal technique (Bejarano, 1987), as a component of collaborative professional learning (Dove & Honigsfeld, 2010; Hansen-Thomas & Richins, 2015) and as a teaching practice of mentors and faculty in teacher education programs (Martel, 2021; Stoynoff, 1999). To our knowledge there have not been any studies that examined the impact of instructional coaching on ESL teacher learning or the formation of coaching partnerships in ESL teacher development, specifically.

Most research on coaching in the field of ELT has examined the use of coaching to help U.S. teachers who are not language specialists but have English learners in their classrooms to implement practices to support English learners, as opposed to the coaching of current or future ESL and English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers. Song (2016) and Brancard and Quinnwilliams (2012) found teachers’ beliefs about English learners and practice teaching English learners changed positively as a result of professional development that included guided or instructional coaching, respectively. However, coaching was not examined as an isolated element. Another body of research has explored a sociocultural, performance-based instructional coaching model developed by Teemant and colleagues and has found that this model is effective in fostering pedagogical transformation in elementary and secondary teachers who teach diverse learners (Teemant, 2014; Teemant et al., 2015; Teemant & Hausman, 2013; Teemant et al., 2014; Teemant, & Reveles, 2012; Teemant et al., 2011).

Russell (2015) explored the use of instructional coaching between an English learner facilitator and a novice high school biology teacher and found that the relationship was supportive to the novice teacher and also contributed to her professional development. The English learner facilitator was found to balance the novice teacher’s needs and concerns with her own sense of what the focus of coaching cycles should be. She observed and also participated actively in the classroom by providing suggestions during instruction. Outside of instructional time, the English learner facilitator used data as a way of helping the novice teacher draw her own conclusions about instruction. Russell (2015) concludes that

they negotiated a joint enterprise based on the EL [English learner] facilitator’s and novice teacher’s participation and symbiotic relationship to accomplish goals and, ultimately, the creation of a shared repertoire that enabled the novice teacher to draw on the resources that emerged from their work together. (p. 43)

Cooper (2008) also highlights the importance of joint data analysis and providing suggestions in a way that allows the coached individual to solve problems and make decisions in a reflection on her own personal experience coaching an administrator to work with English learners. Although content teachers and ESL and EFL teachers would likely differ in their readiness to teach English learners, the transformative potential of coaching found in these studies is a promising indicator that coaching would support the professional development of ESL teachers, particularly in pre-service.

When it comes to pre-service teacher education, the use of coaching appears to be relatively uncommon in all disciplines. Salter (2007) interviewed experienced teachers to explore the use of mentoring and coaching with pre-service teachers in order to understand the use of mentoring over coaching with pre-service teachers. Although she acknowledges there is some overlap in the features and methods of mentoring and coaching, her findings suggest that mentoring tends more often to use a directive approach and to assume that mentors will serve as experienced role models for pre-service teachers; coaching, however, is characterized by coachee-driven goal setting and non-evaluative feedback. In other words, coaching “focuses…on supporting the coachee to set their own agenda and find their own solutions” (Salter, 2007, p. 71).

The research that does exist on coaching and peer-coaching of pre-service teachers is promising but limited. Two important findings of Stahl et al.’s (2018) review of twenty-five studies on coaching and peer-coaching of pre-service teachers are that (1) most pre-service teachers found coaching supportive and valuable and (2) coaching helped pre-service teachers improve their practice. Strieker et al.’s (2014) analysis of forty-three instructional coaching cases during teaching practicums found that coaching may support both the pre-service teacher and the supervising practitioner. Literature on peer coaching indicates that many of the same key components in instructional coaching are also important when peer coaching is implemented amongst pre-service teachers: trust, collaboration, conferencing, data collection, feedback, and analysis and reflection (Britton & Anderson, 2010; Stahl et al., 2018). Vacilotto and Cummings (2007) also point out that “the effectiveness of the peer coach interaction depends on…how aware of their actions teachers can become, how clearly they can describe those actions, and how willing they are to discuss them” (p. 154).

Since research on instructional coaching in pre-service ELT programs is limited, we have included studies that have focused on the use of peer-coaching with pre-service teachers within the field. In a mixed-method study by Kuru Gonen (2016), which examined the participation of 12 pre-service teachers in a reflective reciprocal peer coaching program in a Turkish ELT context, it was found that pre-service teachers improved their reflective practice during the peer coaching program. Goker (2006) found an increase of self-efficacy and development of instructional skills that make content clear, such as communicating lesson objectives, repeating important information and information students do not understand, providing examples, asking questions, giving students opportunities to ask questions, and giving practice opportunities, in a group of 16 pre-service teachers who took part in a peer coaching program as part of a student teaching practicum in a B.A. in Teaching English as a Foreign Language teacher education program in Cyprus. In this study, the experimental (n = 16) and control group (n = 16) participants were randomly assigned to conditions and both experienced 12 teaching observations. The differences in the two groups were that (1) the student teachers in the control group only received feedback from authority figures (faculty), (2) feedback was sometimes not received directly following the observation, and (3) sometimes student teacher descriptions of lessons were used instead of direct observation of teaching. The experimental group student teachers, on the other hand, were observed twice by faculty and ten times by peers, and all post-conferences immediately followed direct observation of teaching. In addition to increased self-efficacy and the targeted teaching skills, the data also suggest that the experimental group pre-service teachers who participated in peer coaching felt “a sense of freedom to ask questions” (Goker, 2006, p. 251), received more consistent feedback and had more time to discuss strategies than control group pre-service teachers who received traditional supervision from faculty. Vacilotto and Cummings (2007) explored the implementation of peer coaching for professional development of pre-service ESL/EFL teachers in Brazil. They found that observations and discussions, in particular, helped the participants develop teaching skills. It was also noted that “collaboration helped student teachers feel confident enough to try out various methods and procedures that they had studied” (Vacilotto & Cummings, 2007, p. 156). An interesting finding was the lack of consensus among the participants as to what type of feedback (e.g., positive, negative) was most effective. The authors commented on the potential for coaching to reduce stress but they were also hesitant to draw conclusions about how coaching could meet professional development needs beyond the immediate context, noting that “[b]ecause of their status as graduate students, the participants of this study may have been more likely to readily experiment with peer coaching” (Vacilotto & Cummings, 2007, p. 159). This observation serves as a reminder that the effectiveness of coaching for professional growth is related to the nature of the relationship between the coach and coachee and the situational context and how it influences interpersonal dynamics.

In sum, the literature suggests that instructional coaching has the potential to be a powerful professional development model in ELT. In-service content teachers demonstrated professional development as a result of coaching with a focus on meeting the needs of diverse learners (Teemant et al., 2015; Teemant & Reveles, 2012; Teemant et al., 2011) and English learners specifically (Brancard & Quinnwilliams, 2012; Russell, 2016; Song, 2016). Yet, it remains to be explored how pre-service ESL and EFL teachers could benefit from instructional coaching. Studies of peer coaching of pre-service teachers in ELT suggest that a collaborative and trusting relationship, consistent feedback and ample time for dialogue are positive components of coaching that may be associated with the development of self-efficacy, professional growth and decrease of stress and anxiety. These findings are also promising, but it is critical to examine if and how coaching partnerships between pre-service teachers and faculty members may navigate power dynamics and have similar affective outcomes as those of peer coaching partnerships in previous studies. This study seeks to address these gaps in the literature by examining one case study of an instructional coaching partnership between an ELT faculty member and a pre-service ESL teacher.

Method

Research Design

This research project used an exploratory qualitative case study design to examine the impact of coaching on coach and coachee professional development and the process of a single coaching partnership case (Baxter & Jack, 2008) between an ELT faculty member (Melissa) and a pre-service ESL teacher (Dani), which existed during a specific 10-week course that was designed to prepare multilingual paraprofessionals working in an urban school district in Massachusetts to pass the Communication and Literacy Skills Massachusetts Test for Educator Licensure (MTEL). An exploratory case study was appropriate to gain insight into the development of the coaching partnership, as we did not expect the outcomes of this process to be a simple cause and effect relationship (Yin, 2003). We collected qualitative documents, including emails, journal entries and an audio-recorded conversation, during coaching and performed a document analysis after the coaching partnership concluded. This approach provided two important advantages: (1) we were able to examine the exact wording used by Melissa and Dani as their coaching partnership developed and as they reflected on the partnership and (2) we were able to gather the data without allocating significant time to data collection during the coaching partnership (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This was an important consideration, since Melissa and Dani were new to coaching and wanted to focus their attention on the coaching itself while it was taking place. We implemented data triangulation by collecting varied documents (Patton, 2002), which we describe in detail below.

Context

The curriculum for the 10-week Communication and Literacy Skills MTEL preparation course that Dani taught was developed by the ELT faculty member, (Melissa), in response to a need the school district identified in order to develop test preparation for multilingual paraprofessionals and had been taught by the graduate assistant, Dani, in a previous semester. The curriculum provided English grammar review and academic writing instruction, and course delivery integrated ESL teaching methods, such as wait time, modeling, visual support, a process approach to writing, and differentiation. During the second iteration of the course, Melissa and Dani entered into a coaching partnership, in which Dani taught the course, and Melissa coached Dani (see Figure 1). It is important to note that the decision to use a coaching model was not a result of perceived problems in Dani’s first delivery of the course, but rather came about due to Melissa’s and Dani’s interest in coaching as a professional development model. Prior to data collection, the study was submitted to and approved by Bridgewater State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). An IRB is a group that is responsible for reviewing and approving research projects to ensure that human subjects’ rights and welfare are protected, and most research institutions in the U.S. have institutional IRBs. During the coaching partnership, Melissa attended nine of the ten, one-and-a-half hour sessions of the course. She observed, collected data, modeled specific teaching strategies and offered some co-teaching support during the course sessions. In between sessions Melissa and Dani set goals, debriefed teaching sessions, and planned for upcoming sessions together.

Figure 1: Stages of the study (Note: GAship = Graduate Assistantship)

Participants

Coach

Melissa was a fourth-year faculty member and the practicum coordinator of the TESOL (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages) program at her university. Prior to teaching at the university level, she had spent over a decade teaching at the high school level with about ten years as an ESL teacher. She was a licensed teacher and had taken and passed the Communication and Literacy Skills MTEL test. She had some teaching experience with adult EFL courses on a part-time basis in Germany and as part of an adult education program at her former school district. She had served as supervising practitioner for two students and as program supervisor for over twenty students, but she had never coached nor been coached in her career.

Coached Pre-service Teacher

At the time of the study, Dani was a graduate student in the Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) in TESOL program for initial Massachusetts ESL licensure at her university, and her goal was to teach ESL in an elementary school in Massachusetts. She had recently taken and passed the Communication and Literacy Skills MTEL exam. She was the graduate assistant for the TESOL program for her first year in the program and was about mid-way through her coursework at the time the coaching partnership in this study was established. Dani had previously worked in schools as a paraprofessional, who was specifically assigned to students with learning disabilities. She had also worked in an after-school program and had taught an adult ESL class to parents. The coaching in this study was her first experience with instructional coaching.

Data Sources

Data for this analysis came from four document sources: email correspondence between Melissa and Dani, a transcript of an audio-recorded phone conversation, a reflection journal kept by Melissa over the course of the coaching partnership, and a follow-up survey completed by Dani after the conclusion of the coaching partnership (see Table 1). The email correspondence and phone conversation give insight into the coaching partnership in real time, and the reflection journal and follow-up survey provide insight on Melissa’s and Dani’s thoughts about and perceptions regarding the coaching partnership. The study was approved by the IRB prior to data collection.

Table 1: Data sources

Coaching Conversations: Email Correspondence

Although the data collection plan anticipated collection of a series of regular audio-recorded coaching conversations, in reality, scheduling challenges often led to spontaneous and incremental conversations over the course of the days between classes. Email served as one of the modes of communication about the coaching experience, and included many elements such as setting and revisiting goals, discussing the use and outcomes of certain teaching strategies, and planning for future classes. During times when schedules did not allow for face-to-face meetings or phone calls to debrief after class, these emails provided another way for Melissa and Dani to share their thoughts and respond in a robust way. Emails were copied into a Word document for analysis.

Coaching Conversation: Audio-recorded Phone Conversation

One 24-minute phone conversation was audio-recorded mid-way through the coaching partnership. Although we had hoped to collect more transcripts of oral conversations, we decided to include this data in our analysis because we both felt this conversation was a typical example of our experiences. Furthermore, since the emails also provided documentation of coaching conversation, albeit in a different modality, we viewed the audio-recorded phone call as an additional data source for understanding coaching interactions. The audio-recorded phone conversation was fully transcribed by Melissa. Fillers such as like and you know were not transcribed or were removed from the transcript.

Reflection Journal

Melissa made four entries in a reflection journal (Word document) over the course of the ten-week coaching partnership. No specific prompts were used for the reflection journal.

Follow-up Survey

Dani completed a survey with eight open-ended questions (see Appendix) six weeks after the conclusion of the course and the coaching partnership. A survey was used rather than a reflection journal in an effort to reduce the demand on Dani’s time during the coaching partnership, which occurred during the spring semester when she was also enrolled in graduate courses.

Data Analysis

Dani completed a preliminary read-through of the data, with the exception of the audio-recorded phone conversation, to gain a general sense of the data and she identified preliminary themes in the data. After Melissa transcribed the audio-recorded phone conversation, she used an inductive coding process, in which the codes come from the data itself as opposed to from a theoretical position (Xu & Zammit, 2020), on all data in Microsoft Word. Twenty codes emerged in the analysis, and these were grouped into the following four themes: interpersonal dynamics, coaching strategies, coaching outcomes, and challenges. The coded data was member-checked by Dani. Member-checking is a verification strategy to ensure internal validity in which "[t]he informant will serve as a check throughout the analysis process. An ongoing dialogue regarding [the researcher’s] interpretations of the informant’s reality and meanings will ensure the truth value of the data” (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 208).

Results

Interpersonal Relationships

As indicated in the literature, a strong relationship and trust are critical for the success of a coaching partnership. A range of characteristics seemed to contribute to a positive interpersonal dynamic between Melissa and Dani, and this in turn appeared to support the overall effectiveness of the coaching partnership.

From the outset in the data, Melissa’s concern about taking over is evident and emerged as one aspect of her professional growth. For example, Melissa asks Dani if Dani wants Melissa to attend the first class or wait until Dani has taught the students once or twice so that the students will recognize Dani as the lead teacher. Melissa noted in her journal entry (Week 1): “I also don’t want to take over when she is teaching or jump in in a way that would seem like I was trying to “repair” or “correct” something in her teaching” and later in a journal entry (Week 5) she thought critically about a specific moment when she questioned her own participation:

During the lesson at one point, I jumped in to ask a student about how she came to an answer about commas, and then I talked through the answer. This is something Dani also does with students and it is a good practice I want to reinforce. I think in that moment I should have probably allowed Dani to continue her instruction so that she could work on developing this in her own practice.

The coaching practice of data collection and analysis seemed to be a helpful alternative to personal reflection or evaluation for Melissa to support Dani in strengthening her practice. In contrast to Melissa’s concerns about taking over, the data did not reveal a concern on Dani’s part that Melissa might take over, and email exchanges demonstrate Dani’s autonomy and ownership through reflective conversation with Melissa. For example, after the first session of the course, Dani and Melissa exchanged emails containing the following three consecutive excerpts about which stage of the writing process should be the focus of the writing workshop time for the paraprofessionals in the upcoming session:

Dani: My main question was how we would use our workshop time this week. Will we go over the write around results/workshop as groups, or just give the feedback separately and use the workshop to jump into the next writing practice?

Melissa: What do you think is most useful, given your experience in the previous course? I do want to make sure that students have enough time to revise or write, but some time could be allocated to oral feedback if you think that would be helpful to the group.

Dani: I think having the workshop time to revise or write would be most useful for students. I think I'll mention the write around and give a very brief bit of oral feedback in addition to the more extensive written feedback, but I would like the majority of the workshop time to be spent on revising or writing.

We can see that Dani moves from a collaborative approach in her first email, where she uses the pronoun we, to arrive at her own decision in the later response, where she uses the pronoun I. At the same time, her confidence also seems to result in part from the opportunity to discuss ideas with Melissa and get feedback before making a final decision on a plan for the next lesson.

Dani demonstrated some typical nervousness about teaching in general, noting in the follow-up survey:

It can be very overwhelming to go into a class on your own, and while having someone simply offer advice or strategies can help, nothing quite compares to having that person there with you to actually see how you carry out those strategies and then give you direct feedback.

Melissa seemed in tune to that nervousness, when she wrote in a journal entry (Week 2) about how she shared with Dani that she also doesn’t always know how something will work and reflecting “I hope it also took off some of the pressure that a tweak or new approach would change the level of engagement.” Initially, the coaching partnership itself made Dani a little nervous. She reflected:

I felt comfortable having a coach in the classroom, more so as the class went on. At first, I was a bit uncomfortable and nervous, as if I was being observed or critiqued. As we got into more of a partnership and established the reciprocity of dialogue, however, I could see the coach as more of a person who is there to help me grow rather than to evaluate me, and this made me feel not only comfortable with having the coach in the classroom, but welcoming it. (Follow-up survey)

Yet, over time, some aspects of the coaching partnership may have actually reduced Dani’s nervousness. She noted that “co-planning and co-teaching were a nice way to take some of the pressure off of me as a teacher” and that discussions and feedback from Melissa built her confidence.

Dani and Melissa set clear goals at the outset and revisited them. Melissa also repeated back what she understood about Dani’s goals and what she expected to do in the upcoming sessions (e.g., model a teaching technique, gather data). For example, in email correspondence from Week 1, Melissa wrote:

I noted from our conversation on Monday that your two goals for coaching were:

-Increase student engagement

-Facilitate smooth transitions

Let me know if there was anything else that you thought of after.

In later email correspondence, Melissa discussed the original goals with Dani and whether the goals could be refined or had been met:

I wanted to just summarize our next steps and the refining of your goals to make sure we're on the same page.

The original goals were to (1) increase engagement and (2) focus on smooth transitions. We have both observed increased engagement over time and in particular when students are doing group work (and also during the writing workshop, as long as there is enough time for them to accomplish something meaningful - I think this is what you were saying about Student[1]?). In this upcoming session we are going to observe some of the students who have been less engaged during whole group instruction (e.g., Student, Student) and think about what results in more/less engagement for them.

… We haven't talked as much about transitions in the last few sessions but it came up today when we talked about differentiating. How are you feeling with this goal? Is there still refinement work to do or are the pieces you added earlier giving you the results you wanted to see? (Week 4, email correspondence)

These clear goals and expectations may have helped situate the focus of the partnership on student outcomes and also given Dani agency in what she received feedback on, thereby making the feedback more useful and anticipated as opposed to negative or intimidating.

Melissa and Dani communicated about how they were experiencing the coaching partnership. At one point toward the end of the course, when Dani’s schedule had changed and Melissa and Dani were having trouble finding times that were mutually convenient for conferences, Melissa wrote:

I can be available during the class tomorrow to think about pacing or any other area you'd like me to. I'm also still available afterward if that is still a good time to meet. Or, Dani, if having me along for these last two classes is really feeling like more work and time than you have right now, that is also fine and won't hurt my feelings. I realize coaching takes more time than just teaching. (week 8, email correspondence)

Dani’s response acknowledges the additional time required to participate in the coaching partnership, which suggests that she feels comfortable sharing this drawback with Melissa:

I would love to still have you come to these final two classes. While the planning and collaborating is more work, I have found it very helpful, especially the piece of having you present in class. Even if I prepare the materials alone and we can discuss the class after class during that period, that would be super helpful.

A team element was most evident in the email and phone coaching conversation data when Melissa asked Dani what she could do to help her prepare for class, she responded enthusiastically when a new strategy went well and took a problem-solving approach to challenges Dani brought up. It is also evident in Dani’s openness to a coaching partnership, requests for specific feedback and in her detailed contributions and reflections. The real-time conversations demonstrate how Dani and Melissa shared the responsibility for the work and outcomes of the class:

I wonder if maybe one thing that we want to think about is…because I think that we’ve seen some positive increase in engagement over four sessions, you know really thinking about it and looking at it. Maybe a focus for the next session is those people. And kind of looking specifically at their engagement. And seeing if there are specific things that either one of us could do. (Melissa, phone conversation)

Melissa made suggestions about what she and Dani could focus on, but also required Dani’s input before moving forward. Dani’s goals and requests for specific feedback framed the coaching conversations.

Rich Professional Development

The coaching partnership contributed to meaningful professional development for both Dani and Melissa; the coaching partnership was characterized by specific feedback, rich and detailed conversation about teaching, observation, data analysis, and trying out new teaching strategies.

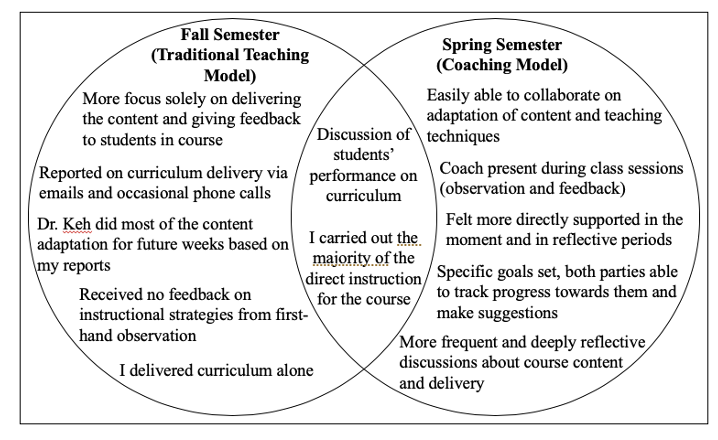

In her preliminary analysis of the data, Dani compared her first semester teaching the course without Melissa as a coach to her second semester teaching the course with Melissa coaching and noted more “in-the-moment” support and more active collaboration on the content being delivered when she was coached. Additionally, she felt more directly supported both while teaching and outside the classroom through discussions that were more frequent and deeply reflective about the course content and the course delivery (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dani’s comparison of teaching the MTEL preparation course without and with the coaching partnership

Melissa compared the coaching partnership to her experiences as a program supervisor for ESL student teaching practicums:

It is a shift for me to not always offer suggestions or tell someone what I think was strong or an area for improvement in teaching because that is what I’ve been used to doing in the CAP [student teaching assessment]. It feels like a luxury to think that I’ll be able to have conversations with Dani over 8-10 class sessions rather than just pop in twice to evaluate a lesson. (Reflection journal entry)

In week 9, Melissa continued to note differences in the nature of supervision during student teaching and coaching:

This is such a contrast to the CAP, where I only do two observations and I don’t really get a chance to dialogue with students at all about the PROCESS of planning, teaching, assessing, planning, etc. I don’t feel like I am able to impact their practice much at all (and maybe that is more of the supervising practitioner’s role), and the conversations seem much more focused on what I noticed than what the teacher’s goals were. (Reflection journal entry)

There is evidence in both Dani’s and Melissa’s reflections that coaching enriched Dani’s learning during this practical teaching experience through conversations that were associated with a higher level of collaboration and reflection than conversations in other ESL pre-service teaching experiences.

Although specific feedback is not unique to coaching, we noted in this case that specific feedback originated not from the coach, but out of the coaching partnership, as Dani was active in requesting specific feedback on her teaching. This is evident in an email from Dani in week 2:

With so many people having struggled at least a bit with detail selection for this summary, I was torn as to whether I should keep the exercise of selecting details for the cell phones, and reviewing them as a whole group after, then moving on to the new piece (finding the main and controlling idea, then going into the workshop) or if I should just add a slide addressing the details and structure for the cell phone piece, maybe showing my sample outline, and keep the exercise for use on the new piece at the end. What are your thoughts on this?

Dani conveys and involves Melissa in her thought process, communicating that she was “torn” and asking directly for Melissa’s thoughts. In a later email Dani also details her thoughts about helping students generate examples and expresses that she is “a bit stuck.”

In addition to components that may be evident in a range of mentoring experiences, we noted three unique coaching techniques that provided opportunities for professional learning in the coaching partnership. First, Melissa occasionally used modeling so Dani could see how a new technique could work with Dani’s particular students. Dani reflected on the value of this element to her growth and confidence:

I learn a lot by watching, so being able to see techniques modeled for me was a huge help. Whether I took notes physically or just carefully watched both the coach and students while instructional techniques were modeled, I felt that I could compare what I originally envisioned that strategy to look like with how the coach used it, and use both of these perspectives combined with how the students responded to the coach’s use of the technique to figure out how I would use that technique in the future. This feature of coaching definitely helped ease my anxiety in the classroom and let me see how a more experienced professional would actually do something, rather than just hearing “maybe try x technique.” (Follow-up survey)

One interesting outcome of the use of modeling was that Melissa occasionally provided a window into her own reflective practice during conversations with Dani, as the two discussed Melissa’s teaching. The use of this second technique is evident in the phone conversation from week 4. Melissa had modeled a technique to increase engagement when groups shared their answers and reflected on it when communicating with Dani:

I also realized that there was something that I would change if I did this again…was to really get a sense of how far people got because when I got to the last table [students were seated at large tables where six students could sit comfortably and work collaboratively] they hadn’t done the final question and so if I had been paying better attention I would have started…there was one table that had done all four and I would have started with a different table so that each table really did get to give their answer.

Melissa’s knowledge of the students emerged as a third technique in coaching conversations that enabled Dani to work through teaching questions with Melissa. Dani and Melissa discussed specific students and what they had learned about them, and Dani reflected that “[h]aving a coach there in person who can get to know the students alongside me can provide valuable insight into student learning” (Follow-up survey).

Professional Growth

In the email correspondence and in the particular phone conversation, “tinkering” is evident, in which Melissa and Dani spend a good amount of time bringing up ideas for small adjustments and discussing how they might work with the group of students. Melissa referred to the coaching partnership in her week 2 journal as a professional development format that is characterized by experimentation and adjustment in the classroom, and the email correspondence, such as the exchange above about the use of workshop time, also show how Melissa and Dani exchange ideas and collaboratively arrive at one to implement and reflect on. This outcome appears to be related to the coaching techniques of rich conversation, data analysis, and the coach’s knowledge of the students as well as the interpersonal components of listening and a team-building element.

Although Dani mentioned that the coaching partnership required more time in some ways (as seen above where Dani notes that planning and collaborating is more time-consuming), she also commented that the coaching partnership resulted in a reduction of number of tasks for her:

I felt like the first time I taught this class, when I taught without a coach, I had to both teach and observe at the same time to figure out what was getting students engaged. Having a coach who can watch both me and my students as I teach to see what elicits what responses from students was helpful, and took a lot of pressure off of me. (Follow-up survey)

The data also indicate that the coaching partnership provided preparation for future teaching for Dani and professional development for Melissa. Dani noted “I took away quite a few strategies from instructional coaching that I have already implemented in my classroom, or that I will implement in the future” (Follow-up survey) and that acquiring resources for teaching during the coaching partnership “made me feel better prepared and like I would be able to find more resources for myself in the future” (Follow-up survey). Melissa queried “Perhaps…there is some way to bring some of the coaching elements into the CAP observations by including a pre-observation conversation and asking the teacher candidate to choose some goals/focus for observation” (Week 5, Reflection journal entry).

Logistic Challenges

Although our data generally reveal an effective coaching partnership and positive outcomes of coaching for the development of pre-service ESL teachers, a few challenges were evident in our data. We noted a desire for regular sessions and scheduling challenges as two interrelated issues. The need for regular sessions was evident in Dani’s preference to have Melissa observe and debrief each teaching session:

The main issue I had was consistency of the debriefs towards the end of the class, but that was due to both myself and the coach having very busy schedules at the end of the semester. It did feel a bit odd to not have such a detailed debrief and discussion for a week or two at a time after having that consistency in the beginning of the semester. A more solidly scheduled meeting time, whether in person or over the phone, that was consistent from week to week from the beginning of the class to its end may have helped this. (Follow-up survey)

Scheduling challenges were apparent at times when Melissa and Dani could not find a mutually convenient time for the debrief and planning stages of the coaching cycle. While the intention was initially to have more blocked-out time for coaching conversations, these scheduling conflicts meant that often these debriefs would be either more organic conversations in a meeting or phone call or would take place through email correspondences instead.

It is worth noting that Melissa’s concern about taking over and Dani’s nervousness, which were mentioned above under interpersonal dynamics, could be challenges in other coaching partnerships, but they were not discussed as challenges in this case because they diminished over the course of the coaching partnership.

Discussion

The goals of this case study were to explore the impact of a coaching partnership on a pre-service ESL teacher’s teaching experience and to learn about the process of forming a coaching partnership in the field of ELT. Although it was not surprising that interpersonal dynamics between Dani and Melissa supported the development and the effectiveness of the coaching partnership, the data provide a valuable window on the nature of communications that contributed to that positive dynamic. The relationship developed over time and was supported by initial and iterative goal setting, openness to the coaching partnership and direct communication. These elements in turn facilitated collaboration and seemed to have mitigated power imbalances in- and outside of the classroom. Dani and Melissa took care to build a relationship and establish trust, which research indicates would facilitate the effectiveness of coaching as a professional development model (Chamberlin, 2000; Kuru Gonen, 2016; Russell, 2015; Stahl et al., 2018; Vacilotto & Cummings, 2007). Importantly, it was clear how the coached pre-service teacher was an active collaborator in building a “joint enterprise” (Russell, 2015, p. 43). This highlights the need to learn more about the power and agency pre-service teachers hold in an instructional coaching model and ways that coaching can be implemented to maximize power and agency.

The findings suggest that the focal coaching partnership allowed for rich use of elements to support pre-service teacher growth, including specific feedback, rich and detailed conversation about teaching, observation, data analysis, and trying out new strategies. Three elements emerged in the data that were less prevalent in previous research and which may also be unique to coaching compared to other types of pre-service learning experiences. These three elements were modeling, the coach’s familiarity with students and opportunities to experience the coach’s own reflective practice. The collaborative nature of specific feedback was also noteworthy in the data.

In this case study, modeling and the coach’s familiarity with students benefited the pre-service teacher. These coaching strategies were identified in the literature on instructional coaching for in-service teachers (Russell, 2016; Salter, 2007) but were not as prevalent in the pre-service teacher research contexts, possibly because that research primarily examined peer coaching as opposed to instructional coaching and tended to include fewer coaching cycles than were used in this study. Although Dani’s goals were not focused exclusively on the multilingual adults in the group, Melissa and Dani conversed about how to adjust pacing for engagement of one of the multilingual learners specifically. Consequently, we speculate that the coach’s familiarity with the coachee’s students has the potential to be an especially powerful tool to support differentiation in ESL teaching. The English learner population is incredibly diverse, and the ability to adjust instruction in response to individual student outcomes is critical for ESL teachers (Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2018; TESOL International Association, 2019; Wisconsin Center for Education Research, 2012). Future research should examine more closely how this element of coaching can support pre-service ESL teachers to develop the ability to differentiate instruction.

One surprising finding about coaching outcomes was that coaching allowed for the coach’s professional growth. Our results indicate that Melissa engaged in self-reflection and found valuable strategies for her own practice through her experience as a coach. In the research reviewed for this study, professional growth of the coach is touched upon in Cooper’s (2008) reflection when she refers to part of a meeting with the administrator she coached as “enlightening” and notes: “[i]t fascinated me to see how this administrator was making decisions” and in Martel’s (2021) reflection that “I would like to take the time to more deeply analyze my coaching practice, in the spirit of building my own capacity as a language teacher educator. I realized…just how complex a task coaching is.” Research focused more generally on collaborative practices in teaching has also indicated such practices may contribute to developing teacher leadership (Dove & Honigsfeld, 2010).

Our findings point to practical considerations for implementing an instructional coaching model in pre-service teaching programs in ELT. It was evident that the time-consuming nature of coaching alongside scheduling issues presented challenges during the coaching partnership. By comparison, it was interesting to see that coaching was viewed as easy to implement and necessitating little preparation in some studies (Britton & Anderson, 2010) and time-consuming in others (Stoynoff, 1999; Vacilotto & Cummings, 2007). These conflicting findings suggest the need to consider carefully the time required to implement a coaching experience during a pre-service program. Furthermore, as coaching partnerships are formed, they may be enhanced by preliminary discussion of time commitment and/or plan for pre-established meeting times in between instructional observations. However, care should be taken to retain some flexibility, as pre-service teachers also need to devote time and energy to lesson preparation and delivery. Setting aside time for coaching conversations would also be advantageous in future research and would address a limitation of our study, namely the inclusion of only one audio-recorded phone conversation.

Although this study examined only one coaching partnership and this narrow focus limits the generalizability of the results, the focal case provides rich description of how a coaching partnership can form and support pre-service teacher development in TESOL through the use of specific coaching strategies.

Acknowledgement

This work was made possible in part by a grant from the Bridgewater State University Center for Research and Scholarship.

References

Anderson, N.J. (2018). The five Ps of effective professional development for language teachers. MEXTESOL Journal, 42(2). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=3416

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

Bejarano, Y. (1987). A cooperative small-group methodology in the language classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 21(3), 483-504. http://doi.org/10.2307/3586499

Brancard, R., & Quinnwilliams, J. (2012). Learning labs: Collaborations for transformative teacher learning. TESOL Journal, 3(3), 320-349. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.22

Britton, L. R., & Anderson, K. A. (2010). Peer coaching and pre-service teachers: Examining an underutilized concept. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 306-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.008

Chamberlin, C. R. (2000). TESL degree candidates’ perceptions of trust in supervisors. TESOL Quarterly, 34(4), 653-673. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587780

Cho, S., & Clark-Gareca, B. (2020). Approximating and innovating field experiences of ESOL preservice teachers: The effects of COVID-19 and school closures. TESOL Journal, 11(3).. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.548

Clemente, M. A. (2004). Teacher awareness: An essential element of ELT education. MEXTESOL Journal, 27(3). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/public/files/118e55ae3ca98e518bb060b736b22108.pdf

Cooper, A. (2008). Instructional coaching for English language educators. Compleat Links, 5(4). https://www.tesol.org/read-and-publish/journals/other-serial-publications/compleat-links/compleat-links-volume-5-issue-4-(december-2008)/instructional-coaching-for-english-language-educators

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Dove, M., & Honigsfeld, A. (2010). ESL coteaching and collaboration: Opportunities to develop teacher leadership and enhance student learning. TESOL Journal, 1(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.5054/tj.2010.214879

Goker, S. D. (2006). Impact of peer coaching on self-efficacy and instructional skills in TEFL teacher education. System, 34(2), 239-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.12.002

Kuru Gonen, S. I. (2016). A study on reflective reciprocal peer coaching for pre-service teachers: Change in reflectivity. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(7). https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i7.1452

Hansen-Thomas, H., & Richins, L G.. (2015). ESL mentoring for secondary rural educators: Math and science teachers become second language specialists through collaboration. TESOL Journal, 6(4), 766-776 https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.221

Knight, J. (2007). Instructional coaching: A partnership approach to improving instruction. Corwin Press.

Lengeling, M. M., & Wilson, A. K. (2017). Weaving together teacher development and narrative inquiry: A conversation with Paula R. Golombek. MEXTESOL Journal, 41(4), 1-5. https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=2622

Martel, J. (2021). Implementing “enhanced rehearsals” in a practice-based TESOL methods course. TESOL Journal, 12(2).https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.540

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2018). Massachusetts model system for educator evaluation: Classroom teacher rubric.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Richards, J. C. & Crookes, G. (1988). The practicum in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 22(1), 9-27. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587059

Russell, F. A. (2015). Learning to teach English learners: Instructional coaching and developing novice high school teacher capacity. Teacher Education Quarterly, 42(1), 27-47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/teaceducquar.42.1.27

Salter, T. (2015). Equality of mentoring and coaching opportunity: Making both available to pre-service teachers. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 4(1), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-08-2014-0031

Song, K.H. (2016). Systematic professional development training and its impact on teachers’ attitudes toward ELLs: SIOP and guided coaching. TESOL Journal, 7(4), 767-799. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.240

Stahl, G., Sharplin, E., & Kehrwald, B. (2018). Real-time coaching and pre-service teacher education. Springer.

Stoynoff, S. (1999). The TESOL practicum: An integrated model in the U.S. TESOL Quarterly, 33(1), 145-151. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588200

Strieker, T. S., Shaheen, M., Hubbard, D., Digiovanni L., & Lim, W. (2014). Transforming clinical practice in teacher education through pre-service co-teaching and coaching. Educational Renaissance, 2(2), 39-62. https://doi.org/10.33499/edren.v2i2.71

Teemant, A. (2014). A mixed methods investigation of instructional coaching for teachers of diverse learners. Urban Education, 49(5), 574-604. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0042085913481362

Teemant, A., Cen, Y., & Wilson, A. (2015). Effects of ESL instructional coaching on secondary teacher use of sociocultural instructional practices. INTESOL Journal, 12(2), 1-29. https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/intesol/index

Teemant, A., & Hausman, C. S. (2013). The relationship of teacher use of critical sociocultural practices with student achievement. Critical Education, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.14288/ce.v4i4

Teemant, A., Leland, C., & Berghoff, B. (2014). Development and validation of a measure of Critical Stance for instructional coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 136-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.008

Teemant, A., & Reveles, C. (2012). Mainstream ESL instructional coaching: A repeated measures replication study. INTESOL Journal, 9(1), 17-34. https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/intesol/article/view/15536/15585

Teemant, A., Wink, J., Tyra, S. (2011). Effects of coaching on teacher use of sociocultural instructional practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 683-693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.006

TESOL International Association (TESOL). (2019). Standards for initial TESOL pre-K-12 teacher preparation programs. TESOL International.

Vacilotto, S., & Cummings, R. (2007). Peer coaching in TEFL/TESL programmes. ELT Journal, 61(2), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm008

Wilcox, G. (2001). Reflective teaching and teacher development. MEXTESOL Journal, 24(4). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/public/files/2749f3c954fe78580114a1ed9773159f.pdf

Wisconsin Center for Education Research (2012). WIDA focus on differentiation: Part I. University of Wisconsin.

Xu, W., & Zammit, K. (2020). Applying thematic analysis to education: A hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920918810

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

[1] Student names have been replaced with “Student” to preserve anonymity.