Introduction

Throughout the years, several governments in Latin America have joined the initiative of providing free textbooks to public primary and secondary schools students. Ministries of Education of countries such as Mexico (Anzures, 2011), Colombia (Graffe & Orrego, 2013), Ecuador (Ministerio de Educación, n.d.a), Chile (Ministerio de Educación, 2010), Argentina (Finnegan, & Serulnikov, 2016), and Uruguay (Canale, 2015) have set policies for either the development of or purchase of school textbooks to be distributed in government-run institutions. In most Latin American countries, it is the Ministry of Education (hereafter ME), through textbook selection commissions or administrative units, who choose and purchase textbooks for teaching English (Ministerio de Educación, 2010; Porto, 2016; Tavares, 2014; Uribe Schroeder, 2005), not offering English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers the possibility to contribute to the evaluation and choice of these teaching materials. In other words, a small group of individuals select all ELT textbooks. What if the choices they make do not match students’ needs and provide little support for their learning process?

Based on the authors’ teaching experience in the Ecuadorian context, the decision-makers tend to be unaware of what happens in the classroom, unfamiliar with this profession (Patarroyo, 2016), or have never been teachers in state institutions. To avoid erroneous decision-making, education authorities should work jointly with the teachers who actually use the textbook series (Banegas, 2018; Chambers, 1997). As suggested by Martínez (2009), decision-makers and EFL teachers together should conduct a thoughtful evaluation of the textbooks at their disposal to determine whether they will meet their needs of teachers and students, helping them to achieve their countries’ language benchmarks.

Textbooks play a crucial role in language teaching (Hashemi & Borhani, 2015). They may become great allies of EFL teachers. Yet, if not selected carefully, they can prove not to be an appropriate support for the achievement of curricular goals (Graves, 2000). Arguments such as these have drawn concern among researchers interested in the field of EFL textbook evaluation worldwide. In Latin America, for example, there are several studies about the EFL textbooks used in each country, which makes evident how much attention has been given to this topic.

The Mexican literature, for instance, sheds light into methods for evaluating EFL textbooks (Camps, 1998) as one of the factors that motivate and demotivate EFL teachers at different educational levels (Johnson, 2001). In Chile, Farías and Cabezas (2015) investigated the ideologies in the textbooks provided by the ME in that country and analyzed their implications. Argentine research in this area mostly focuses on inquiring about cultural issues. Accordingly, Moirano (2012) studied how global culture was present in three EFL textbooks used in two language institutes and a secondary school, and the attitudes of the teachers who were using those textbooks towards culture. These are just a few examples of the multiple studies carried out about this topic in other countries. As you will read in the following sections, however, the situation in Ecuador is a little different.

EFL in Ecuador

EFL was incorporated in the Ecuadorian curriculum of public secondary schools in 1993 as a result of an agreement signed between the Government of Ecuador and the British Council in 1992 to create the Foreign Language Administration of Ecuador (Soto, 2015). This understanding led to the implementation of the Curriculum Reform and Development for the Learning of English - also known as CRADLE project (The British Council, n.d.). Yet, the aforementioned agreement did not include the incorporation of EFL in the curriculum of public primary schools (Soto et al, 2017, p. 236). After almost two decades of being irregularly present under different denominations (2000-2013) and totally absent again (2014-2015), EFL was officially introduced as a subject of its own in the curricular framework for primary schools in Sierra Region in 2016 and those in the Coastal Region in 2017 (Soto et al., 2017).

From 2000 to 2013, EFL was delivered in some public primary schools, but it was not compulsory. As a result, not all students enrolled in this level during those years had the opportunity to learn English. If they did, the learning conditions may not have been suitable. Soto et al. (2017) confirmed that during that time “there was not [an official] curriculum for this level, no [approved] books, no teachers with appropriate qualifications, no guidelines, nothing” (p. 243). For that reason, the government of Ecuador decided to withdraw EFL courses from primary schools from 2014 to 2015. Since 2016, there has been an official curriculum and free textbooks for this level (Ministerio de Educación, n.d.). However, due to the shortage of professionals to supply the teaching demand for this course in elementary schools (Cronquist & Fiszbein, 2017), problems persist.

This means that not all students enrolled in Ecuadorian state primary schools are taking this subject, or at least, not as these students should be. This issue was anticipated in Agreement MINEDUC-ME-2016-00020-A. Here, it was stated that EFL would be progressively incorporated in the curriculum of primary schools (Ministerio de Educación, 2016) “until all primary schools ha[d] the staff with qualifications to teach English” at this level (Soto et al., 2017, p. 242). These circumstances also support the relevancy in giving an account of the materials used as the main aid to teach EFL in Ecuador to learners who may have had little or no contact with this language during their initial years of schooling.

EFL textbooks in Ecuador

From 1993 to 2018, three textbook series were officially used to teach English in all government-funded secondary schools: Our World Through English (OWTE), Postcards, and Viewpoints. The OWTE series was the first. It was produced by the CRADLE project team. Three editions (1993, 1999, & 2005) were developed since the onset of the project. Then the English Teaching Strengthening Project (Advance) replaced the CRADLE project in 2011 (Toranzos, 2018). Advance came into operation in 2012 (Soto, 2015) incorporating the “update of the national curricula of this subject [as well as] the delivery of textbooks aligned to these curricula” [our translation - our italics] (Ministerio de Educación, n.d.c, par. 1).

The OWTE Series was printed by the Ecuadorian publisher EDIMPRES and sold in bookshops all over Ecuador. The cost of the last edition was $5.50 USD (five dollars and fifty cents). Unlike the textbooks used for teaching EFL during the operationalization of the CRADLE Project, the two textbook series used within Advance were distributed to Ecuadorian students enrolled in primary and secondary state schools at no charge (Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural, 2011; Ministerio de Educación, n.d.). Unlike the CRADLE textbooks, these two textbook series were not locally produced (i.e., they were an international series). In 2016, this series was changed again.

One of the reasons for these changes, according to the Ecuadorian Education Law is that “the textbooks must be updated every three years” [our translation - our italics] (Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural, 2011, p. 41). This interrupts the continuity in using those textbook series as well as preventing students and teachers from being acquainted with the materials and attaining better results in their teaching-learning process. In addition, the textbooks procured for certain academic periods may be methodologically sound and they might be changed to other textbooks that are less appropriate. As mentioned at the beginning of the introduction of this work, the selection of textbook series is generally done without consulting learners and classroom teachers. Textbooks are usually imposed on with no prior needs analysis. These circumstances are one more decisive consideration reinforcing the need to delve into the textbooks used for teaching EFL in public secondary schools in Ecuador.

The three textbook series introduced above have been imposed upon EFL teachers as the focal material for the teaching of English. The extent to which the OWTE Series (as a teaching material itself) met the needs of the Ecuadorian context and supported students´ learning process appropriately was not studied during the two decades it was being used, leaving a gap in the history of EFL materials in Ecuador. The same applies to Postcards. Unfortunately, most Ecuadorian teachers are bound to be unfamiliar with the degree to which the textbook selection criteria that decision makers have applied considers…a) students’ and teachers’ needs; b) contextual realities; the extent to which selected textbooks aid to meet curricular goals; and, c) whether the structure of these materials supports students´ learning process.

Research on EFL Textbooks in Ecuador

Unlike Mexico, Chile, and Argentina, there is little literature concerning EFL textbooks in Ecuador. However, some studies are worthwhile to discuss at this point. For instance, Scoggin’s (2009) MA thesis reported the evaluation of three textbooks of the OWTE Series, which was the first textbook series used in Ecuador for teaching EFL in public secondary schools. Scoggin revealed the extent to which the “pedagogical principles used as a framework for developing the [OWTE textbooks were] reflected in the instructional design including the quality and interrelation among the objectives, activities, and assessment tools” (p. 6). The works developed by González, et al. (2015) and Acosta and Cajas (2018) are also important contributions to the Ecuadorian literature in this area. Even though they did not investigate the textbooks domain as such, the results of their studies indicated that textbooks are the most frequently used teaching materials in EFL classes at both secondary and university levels.

The scarcity of literature concerning EFL textbooks in Ecuador and the outcomes stated in González et al. (2015), and Acosta and Cajas (2018) show the urgent necessity to study this topic in this context. Research on EFL textbooks that were or are currently in use in Ecuador would not only inform educators, decision-makers, textbook developers, and other stakeholders about this theme, it could also give a more accurate view of this country’s reality in regards to the use of textbooks. Additionally, research on EFL materials would help these agents to make informed decisions when selecting or developing a textbook series for foreign language learning in Ecuador.

Besides Scoggin´s (2009) study on the OWTE Series, nothing else has directly been reported on EFL textbooks used in Ecuador. Therefore, this paper intends to analyze the three textbooks that were used in the Ecuadorian public secondary schools to teach English to students enrolled in eighth grade. The overriding aim is to provide a descriptive overview on how the structure and design of the textbook units can support the students´ learning process.

This work contributes to literature by providing a deep and comprehensive analysis that exposes the positive points in the process of choosing textbooks for EFL teaching, as well as the aspects that can be improved. In addition, the authors of this work aim at motivating decision-makers to consider the perspectives of the different actors such as EFL teachers and curriculum designers, especially teachers’ views since they are the ones who are day by day in the classrooms, know the reality of their classes, and the needs of the students in regard to the EFL course. This type of analysis can help achieve more informed decisions regarding the use of English textbooks not only in Ecuador but also in other countries with EFL programs.

Methodology

This work provides a descriptive analysis of three textbooks that were used in the Ecuadorian public secondary schools to teach English to students enrolled in the first year of secondary school (eighth grade). The focus of the analysis is on the time devoted for each unit and how the units’ design supported students´ learning of English.

EFL Textbooks under Study

In line with the purpose of this investigation, the textbooks under evaluation were three textbooks the Ecuadorian public secondary schools adopted to teach English to eighth graders from 1993 up to midyear 2019. Each of these textbooks is described below.

OWTE Series Textbook

As specified in Ponce et al. (2009), this textbook series was written by Ecuadorian textbook developers. They considered teachers and learners´ reality in the classroom as well as academic, cultural, and socio-economic aspects. Therefore, OWTE tried to make the learning of English more meaningful for learners by (a) offering content related to different school subjects, (b) including Ecuador-based content and tasks, and (c) giving learners the opportunity to learn from content related to the outer world. For OWTE authors, exchanging messages is pivotal to communication. Therefore, they placed great emphasis on activities that can help learners develop this ability. Finally, considering the way we use our language skills in real life, the organization of the activities in OWTE went from receptive to productive.

Postcards Series Textbook

Postcards is intended for teen learners; therefore, this textbook series offers learners a variety of level-appropriate and personalized communicative activities to make their learning process more meaningful and successful. “Extensive communicative practice, cross-cultural exploration, group and individual projects, song activities, games, and competitions” (Abbs et al., 2012, p. vi) are part of the portfolio of activities presented to Postcards users. To attract the attention of learners, Postcards uses carefully selected visual resources such as photos and illustrations. Cooperative learning and learner autonomy are important in Postcards. The series fosters extensive pair and group work and peer feedback.

Viewpoints Series Textbook

According to Núñez (2016), Viewpoints is a textbook series aimed at secondary school students. “English A1.1 is based on an eclectic but informed series of ideas and constructs in language teaching and learning. [The textbook] derives its theoretical foundations from task-based instruction, cooperative learning, cross-curricular studies and the cross-cultural approach to language teaching and learning” (Núñez, 2016, p. 7) as well as the Multiple Intelligences theory. The units of all textbooks in the Viewpoints series follow the goals and standards of international organizations. They are developed around content from different subject matters and topics to show learners that by learning English they do not only learn a language, but they also get a tool for learning content from other fields. Students’ knowledge in Spanish is important in this series; it is seen as a positive tool for building learners’ knowledge in English and easing their language learning process.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were obtained from examining the student's textbooks and the teacher's guides of the three series under analysis. The structure of the textbooks was analyzed considering two points: the number of units and their divisions and the structural elements that compose the units of each textbook. For the analysis of the structural elements that compose the units of each textbook, we considered the elements suggested by Lepionka (2003). Lepionka’s (2003) proposed that textbooks should contain three elements: openers, integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands, and closers. Openers help the learners to acquaint themselves with the contents and aims of a unit. Integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands are elements that facilitate the learning process by illustrating the content within the units, highlighting important points, providing tips, and engaging learners with the content of each unit. Finally, closers enable the reinforcement and extension of students´ learning. Unit content tends to be treated as a set of isolated items. Closers offer students the possibility of bringing all the knowledge gained throughout a unit together and making sense of it in a more meaningful and practical way.

A checklist (see Table 2) was developed to evaluate the structure of the units of the textbooks considering the elements suggested by Lepionka (2003). The three textbooks were evaluated by the two researchers of this study to avoid missing important details. Each of them evaluated the textbooks individually. Then they compared the results of their evaluation. When they disagreed on an item, they reevaluated the section under discussion and came to an agreement.

Findings and Analysis

Structure of the textbooks

Table 1: Number of units and their divisions

The data reported in Table 1 shows that out of the three textbooks, OWTE is composed of the largest number of units. Castro Juárez (2013) evaluated two of the textbooks used for teaching English in basic education in Mexico. The results of her investigation indicated that the amount of content and number of activities that composed one of the textbooks she evaluated were inappropriate with respect to the time to be completed and the characteristics of its users. In relation to the number of units and the time envisioned to cover them, Graves (2000) pointed out that unrealistic timetable completion is one of the disadvantages of using textbooks. Considering Castro Juárez´s (2013) findings and in line with Graves´ assertion, and based on our experience as teachers, we believe that the number of units of OWTE and the expected delivery time of their content were impractical. Ecuadorian classes have always been large (30 to 40 students per class) and during the time that OWTE was enforced in Ecuadorian public schools, students were characterized by having little or no previous English learning experience. One week and a half of five forty-five minutes class periods per unit might not be enough time for teaching the content of a unit without sacrificing meaningful practice of the target language.

Unlike OWTE, Postcards and Viewpoints are both composed of six units each. In the case of Postcards, Table 1 shows that every unit is not divided into lessons, but 15 to 19 tasks. Viewpoints units, on the other hand, are divided into four lessons each. Hashemi and Borhani (2015) suggested that textbooks should be appropriate for the context and individuals who are using them. From our perspective, in a context like Ecuador (with large classes and students having little background knowledge of English), delivering six textbook units in a school year is more manageable, even for teachers to be able to meet curricular plans successfully. Furthermore, it is pivotal to giving students the possibility of using the content of a unit in different ways. As Nation (1990), Schmitt (2000) and Ur (2009) mention, the more the learner utilizes what he or she is learning, the better learning outcomes he/she gets. If too much content is to be covered in a short period, there might be fewer opportunities for students to rehearse even small pieces of it.

Table 2: Structural elements of the textbook units

Table 2: Structural elements of the textbook units

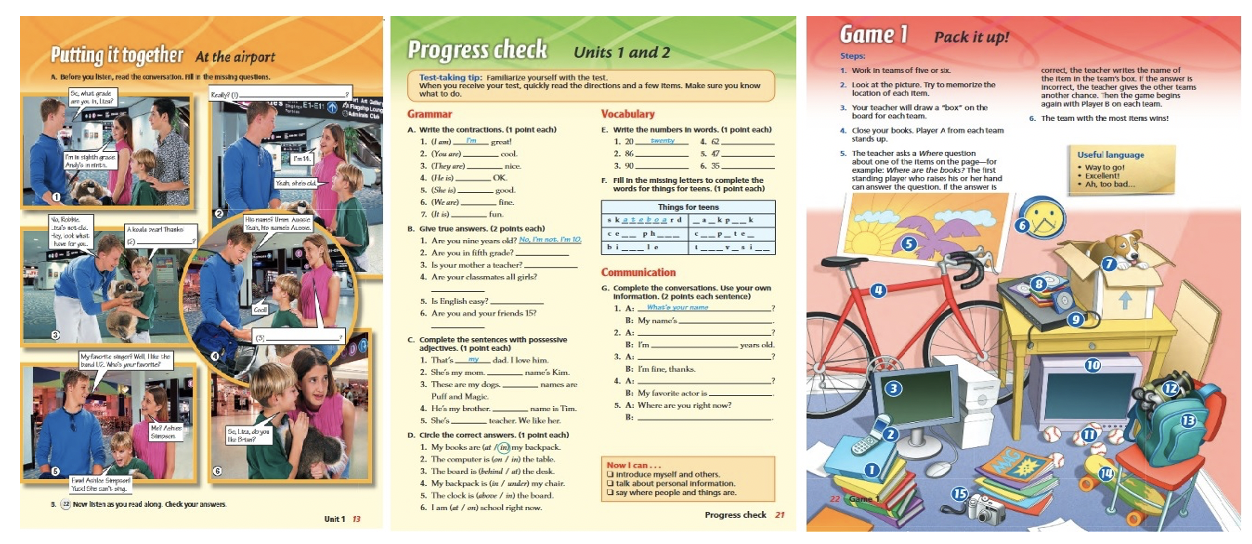

The examination of the units to identify the elements that are part of their design, as displayed in Table 2, revealed that OWTE units did not include any openers. Nogueira (2015) argued that the materials used for language learning “should be presented in a way that creates conditions for learning to be achieved” (p. 15). The absence of openers in OWTEunits prevented learners from becoming familiar with what would be studied throughout them, and therefore, missing an opportunity to help them activate their prior knowledge (Alvermann et al., 1985) and promote better learning (Nogueira, 2015). Postcards, on the other hand, incorporates the learning goals that will guide each unit at the beginning of their first lesson (see Figure 1). Nogueira (2015) stated that goals “provide specific ideas of what students are expected to learn” (p. 12). The goals included in Postcards units encompass communication aims as well as the grammar and vocabulary to be studied. A picture representing a situation is also part of the openers available in the textbook of this series.

Figure 1: Learning goals chart as an example of an opener in Postcards

Figure 1: Learning goals chart as an example of an opener in Postcards

Viewpoints stands out by devoting a whole page for openers (see Figure 2). In this page, learners have access to a thorough overview of the aims of each unit and content to be studied. They also get, in advance, a brief introduction to a project they are expected to develop in each unit. Other elements included in this page are photos and a discussion item aimed at engaging the learners into a conversation about the content of those images. These items are useful to activate and evaluate students’ previous knowledge (Alvermann et al., 1985; Castro Juárez, 2013) as well as to introduce the content of the units. As can be seen from this information, Viewpoints provides a more comprehensive illustration of Lepionka´s (2003) proposal regarding opening elements of a textbook.

Figure 2: Openers page of Viewpoints, which contains a combination of visual aids and a glimpse of the structure of the unit

As for the integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands concerns, OWTE facilitated students’ learning of the content of its units by incorporating pedagogical illustrations and promoting learners’ participation in games, singing, and hands-on activities such as handicrafts and cooking (see Figure 3). OWTE also included tips for learners that addressed classroom language, useful expressions, pronunciation points as well as suggestions about where to go for grammar practice (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 3: Songs and pronunciation points as examples of integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands of OWTE

Figure 4: Game activity as an example of integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strandsof OWTE

Postcards facilitates learning by incorporating three integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands. These elements comprise grammar tables available for learners in every unit as well as pedagogical illustrations that accompany the activities of the units (see Figure 5). They also include a section with recommendations for students, named learning to learn – tips to familiarize themselves with English and ways to enhance their learning habits, among others (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: A grammar table as an example of the integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands of Postcards

Figure 6: Learn to learn tips as an example of the integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands of Postcards

Similar to Postcards, Viewpoints also incorporates grammar tables, pedagogical illustrations, and tips (see Figure 7). The tips in Viewpoints involve listening, speaking, reading, writing, and vocabulary strategies (see Figure 8). Learners are presented with recommendations such as Focus on specific information to get the right answers (listening strategy). This textbook also integrates pronunciation points, key vocabulary, and useful expressions throughout the units (see Figure 7 and Figure 8). In addition to these features, Viewpoints adds a project element in each unit (see Figure 8). Each project is divided into stages that work as wrapping up activities for every lesson. They require students to connect the content studied in each lesson in a meaningful way as they work towards a final unit product.

Therefore, if we accept Nogueira’s (2015) advice, “a range of activities should be presented [in textbooks] to ensure meaning-focused input and output, and language-focused learning” (p. 15), the three textbooks under evaluation offer varied integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands to facilitate learning. This indicates that with reference to these elements, OWTE, Postcards and Viewpoints have been arranged with features that pave the way for effective language learning. However, some motivating pedagogical devices such as games and songs are missing in Postcards and Viewpoints units. The textbooks that Castro Juárez (2013) evaluated lacked this feature as well.

Figure 7: Grammar tables, pedagogical illustrations and tips as examples of integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands of Viewpoints

Figure 8: Listening tip and vocabulary key expressions as an example of integrated pedagogical devices and interior feature strands of Viewpoints

Finally, we consider closers. OWTE units did not incorporate any of these activities, causing a lack of what Lepionka (2003) advocated as potential activities to integrate and put all the knowledge gained throughout a unit into practice in a comprehensive and meaningful way. Conversely, Postcards offers students the possibility of extending their knowledge by performing a variety of activities (see Figure 9), such as small listening and speaking exercises in units one, three and five. By the end of Units 2, 4, and 6, students are presented with progress checks to self-evaluate their learning. Similarly, at the end of Units 2 and 5, students are expected to work in games and writing projects. This textbook also supports the reinforcement of students´ learning by offering reading extension activities at the end of Units 3 and 6. Song-based and culture-related activities are also included at the end of the six units.

Figure 9: Speaking activities, progress checks and games as examples of closers of Postcards

Figure 9: Speaking activities, progress checks and games as examples of closers of Postcards

Similar to Postcards, Viewpoints offers a variety of closers for the reinforcement and extension of students´ learning as well (see Figure 10). All the units end with a glossary, quiz, and self-assessment activity. Learners must also put together all the pieces of work resulting from the project activities they developed throughout the lessons of the units. With this data, students are expected to complete a substantial final product and present it to their class (project sharing). Likewise, in every unit students are presented with either comics (Units 1, 3, & 5) or games (Units 2, 4, & 6).

Figure 10: Speaking activities, comics, quizzes, and glossaries as examples of closers of Viewpoints

Figure 10: Speaking activities, comics, quizzes, and glossaries as examples of closers of Viewpoints

Low (1989) viewed the creation of a final product through the integration of content strands as a way of synthetizing the content covered in a unit, and Lepionka (2003) considered the availability of closers in a textbook as an opportunity not only to synthetize the content of a unit but also to make sense of it in a more meaningful way. Based on the results obtained, we can suggest that the closers included in Postcards and Viewpoints may prompt learners to integrate a unit’s content strands in a meaningful and comprehensive way, provoking the reinforcement and extension of the students’ language learning.

Conclusion

OWTE, Postcards, and Viewpoints have individual features that reflect the vision of their authors regarding theories and pedagogical design principles for EFL teaching. They also reveal how much authors expect users to learn from their textbooks. However, not all the contents of these textbooks suited the needs of their users in relation to their linguistic background. OWTE was developed with an ambitious perspective. According to the authors of this series, the textbooks were composed of “a suite of six culturally and methodologically appropriate textbooks to be used in all state schools in Ecuador” (The British Council, n.d., par. 6). Unfortunately, the amount of content that students were expected to be familiar with within a school year seems to be a challenge for individuals who had never taken EFL classes prior to this series. Providing a more manageable amount of content such as the one present in Postcards and Viewpoints enables users (both students and teachers) to cover all the topics proposed in the book in an academic year, at an appropriate pace and achieve better learning outcomes.

Regarding the structural elements of the units and their contribution to students´ learning, the components of the units of Postcards and Viewpoints offer more opportunities for students to practice the language in meaningful ways. However, from a pedagogical perspective, the features found in Viewpoints give more opportunities for students to engage in their learning process and reinforce that learning. In addition, the variety of elements incorporated in this textbook and the way it has been structured indicates its alignment with present day curricular tendencies in teaching (such as CLIL), which suggests that its design is promising for better language learning.

The textbook selection requirements surely respond to the curriculum for EFL and objectives of the ME regarding this course. However, the authors of this work consider that the selection of EFL textbooks should be more comprehensive and contemplate other criteria such as those discussed throughout the current analysis, especially in the findings and analysis section. In this sense, the authors expect that this report can help to inform decision-makers and textbook developers regarding a set of criteria to be considered when making decisions about textbook selection or creation for countries where English is taught as a foreign language. Similarly, they hope that the results of this study shed light into Ecuador´s actual state in this field and serve as a reference for similar countries. Combining the information reported here with the views from decision-makers, textbook designers, teachers and students would enhance this work. Aligned to this reality, researchers interested in investigating this topic have an ample spectrum to contribute to building its literature in future research studies.

References

Abbs, B., Barker, C., Freebairn, I., & Wilson, J. (2012). Postcards 1: Teacher’s Edition. Pearson.

Acosta, H., & Cajas, D. (2018). Analysis of teaching resources used in EFL classes in selected Ecuadorian universities. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 100-109. doi: https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v8i1.11469

Alvermann, D. E.., Smith, L. C., & Readence, J. E. (1985). Prior knowledge activation and the comprehension of compatible and incompatible text. Reading Research Quarterly, 20(4), 420-436. https://doi.org/10.2307/747852

Anzures, T. (2011). El libro de texto gratuito en la actualidad: Logros y retos de un programa cincuentenario [Free textbooks today: Achievements and challenges of a fiftieth anniversary program]. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 16(49), 363-388. http://www.comie.org.mx/revista/v2018/rmie/index.php/nrmie/article/view/376/376

Banegas, D. L. (2018). Evaluating language and content in coursebooks. In M. Azarnoosh, M. Zeraatpishe, A. Faravani, & H. R. Kargozari (Eds.), Issues in coursebook evaluation (pp. 21-29). Brill.

Canale, G. (2015). Mapping conceptual change: The ideological struggle for the meaning of EFL in Uruguayan education. L2 Journal, 7(3), 15-39. https://doi.org/10.5070/L27323707

Castro Juárez, E. (2013). A pedagogical evaluation of textbooks used in Mexico’s National English Program in Basic Education. MEXTESOL Journal, 37(3). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/public/files/5b48c52dfecc4031c0c05a2116b1b019.pdf

Chambers, F. (1997). Seeking consensus in coursebook evaluation. ELT Journal, 51(1), 29-35. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.1.29

Cronquist, K., & Fiszbein, A. (2017). English language learning in Latin America. The Dialogue-Leadership for the Americas.

Farías, M., & Cabezas, D. (2015). Identity imposition in EFL textbooks for adult secondary education in Chile. In I. van de Craats, J. J. H. Kurvers, & R. W. N. M. van Hout (Eds.), Adult literacy, second language, and cognition (pp. 69-88). Radboud University.

Finnegan, F., & Serulnikov, A. (2016). Las políticas públicas de provisión de libros a escuelas y estudiantes: Tendencias y debates en el contexto regional [Public policies for the provision of books to school and students: Trends and debates in the regional context].DiNIEE. http://www.bnm.me.gov.ar/giga1/documentos/EL005557.pdf

González, P., Ochoa, C., Cabrera, P., Castillo, L., Quinonez, A., Solano, L., Espinosa, F., Ulehlova, E., & Arias, M. (2015). EFL Teaching in the Amazon Region of Ecuador: A focus on activities and resources for teaching listening and speaking skills. English Language Teaching, 8(8), 94-103. https://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt/article/download/51406/27569

Graffe, G. J., & Orrego, G. (2013). El texto escolar colombiano y las políticas educativas durante el siglo XX [The Colombian school textbook and educational policies during the 20th century]. Itinerario Educativo, 27(62), 91-113. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6280198.pdf

Graves, K. (2000). Designing language courses: A guide for teachers.. Newbury House

Hashemi, S. Z., & Borhani, A. (2015). Textbook evaluation: An investigation into “American English File” series. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL), 3(5), 47-55. https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v3-i5/6.pdf

Johnson, C. (2001). Factors influencing motivation and de-motivation in Mexican EFL teachers. MEXTESOL Journal, 51-68.http://www.mextesol.net/journal/public/files/fb462fd4080e9fafc0bd89155917cb4d.pdf

Lepionka, M. E. (2003). Writing and developing your college textbook. Atlantic Path.

Ley Orgánica de Educación Intercultural. (2011). Registro Oficial Suplemento 417 [Supplemental Official Register], 31 de marzo de 2011. http://gobiernoabierto.quito.gob.ec/Archivos/Transparencia/2021/04abril/A2/ANEXOS/PROCU_LOEI.pdf

Low, G. (1989). Appropriate design: The internal organization of course units. In R. K. Johnson (Ed.), The second language curriculum(pp. 136-154). Cambridge University Press.

Martínez, N. (2009). Por qué los estudiantes de las escuelas públicas no aprenden inglés [Why public school students do not learn English]. Diálogos, 4, 39-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10972/2032

Ministerio de Educación (n.d.). Textos escolares: Programa de administración escolar-Textos escolares gratuitos. Retrieved from https://educacion.gob.ec/textos-escolares

Ministerio de Educación (2010). Políticas de textos escolares [School textbook policies]. Unidad de Currículum y Evaluación - Ministerio de Educación (Chile).

Ministerio de Educación. (2016). Acuerdo Ministerial No. MINEDUC-ME-2016-00020-A [Ministerial agreement No. MINEDUC-ME-2016-00020-A]. Ecuatorian Government Printing Office.

Moirano, M. C. (2012). Teaching the students and not the book: Addressing the problem of culture teaching in EFL in Argentina. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 6, 71-96. https://latinjournal.org/index.php/gist/article/view/414/359

Nation, I. S. P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. Newbury House.

Núñez, A. (2016). English A1.1, Teacher’s Guide: OCTAVO GRADO - EGB. Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador, Norma.

Patarroyo Fonsesa, M. (2016). Textbooks decontextualization within bilingual education in Colombia. Enletawa Journal, 9(1), 87-104. https://doi.org/10.19053/2011835X.7541

Ponce, R., Rivera, M., Rosero., I., & Miller, K. (2009). OWTE-Our world through English: Teacher’s book 1 (3rd ed.). Edimpres.

Porto, M. (2016). English language education in primary schooling in Argentina. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(80). http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2450

Rodrigues, E. N. (2015). Curriculum design and language learning: An analysis of English textbooks in Brazil [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Andrews University. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1

Salbego, N., Heberle, V. M., & Balen, M. G. S. da S. (2015). A visual analysis of English textbooks: Multimodal scaffolded learning. Calidoscópio,13(1), 5-13. http://revistas.unisinos.br/index.php/calidoscopio/article/view/cld.2015.131.01

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Scoggin, J. (2009). Design principal analysis for the English textbook series Our world through English. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Universidad Casa Grande. http://dspace.casagrande.edu.ec:8080/bitstream/ucasagrande/402/1/Tesis308SCOd.pdf

Soto, S. T. (2015). An analysis of curriculum development. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(6), 1129-1139. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0506.02

Soto, S. T., Intriago, E., Vargas Caicedo, E., Cajamarca Illescas, M., Cárdenas, S., Fabre Merchan, P., Bravo, I., Morales, M. A., Villafuerte, J. S. (2017). English language teaching in Ecuador: An analysis of its evolution within the national curriculum of public primary schools. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, Special Issue for IETC 2017, 235-244.

Tavares, P. O. (2014). Pragmatics in EFL teaching: How speech acts are addressed in a Brazilian textbook series. BELT Journal, 5(1), 30-39. https://doi.org/10.15448/2178-3640.2014.1.18071

The British Council (n.d.). The CRADLE Project, Ecuador. English Agenda. Retrieved November 29th, 2018, from http://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/consultancy/our-track-record/cradle-project-ecuador

Toranzos, M. (22 de enero de 2018). La educación bilingüe, una utopía llena de traspiés: Cuatro iniciativas para mejorar la enseñanza del inglés se han instaurado desde 2011. El nivel de docentes ha subido 24% [Bilingual education, a utopia full of mishaps: Four initiatives to improve the teaching of English have been established since 2011. The level of teachers has risen 24%]. Diario Expreso. https://www.pressreader.com/ecuador/diario-expreso/20180122/281715500036382

Ur, P. (2009). A course in language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge University Press.

Uribe Schroeder, R. (2005). Programas, compras oficiales y dotación de textos escolares en América Latina [Programs, official purchases and provision of school textbooks in Latin America]. Cerlalc. https://cerlalc.org/publicaciones/programas-compras-oficiales-y-dotacion-de-textos-escolares-en-america-latina