Introduction

As stated in the Turkish primary and secondary education curricula (Ministry of National Education, 2018a, 2018b), language education curricula were designed in congruence with the descriptors and principles of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001). The CEFR “provides a common basis for the elaboration of language syllabuses, curriculum guidelines, examinations, textbooks, etc. across Europe” (p.1). Accordingly, any language curriculum adopting the CEFR must aim for language proficiency and communicative competence in the target language. The teaching materials should also be developed in accordance with this objective. To state this differently, the learning outcomes of the language curricula should also include the cultivation of phonologically competent learners because language proficiency encapsulates linguistic competence, which also involves phonological competence (Council of Europe, 2001). It can therefore be assumed that language learners are expected to possess intelligible and clear pronunciation as mandated by a CEFR-adopting language curriculum. Additionally, the textbooks as the teaching materials must also include an appropriate and adequate number of pronunciation activities in keeping with the principles and descriptors of CEFR.

However, it can be observed that pronunciation is excluded from the primary education curriculum and included only marginally in the second education curriculum in Turkey (Ministry of National Education, 2018a, 2018b). Given the significance of pronunciation for effective communication (Pennington & Rogerson-Revell, 2019) and textbooks for language education (Richards, 2015), this study examined the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks published by the Turkish national education ministry with regard to their treatment of pronunciation. To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, no previous studies attempted to explore this issue. Therefore, the study aimed to bridge this literature gap and contribute to English language education in general and pronunciation instruction in Turkey and other contexts where EFL textbooks are utilized.

Rationale for the study

The ultimate goal in language learning is considered to be communicative and proficient in the target language (Harsch, 2017), and pronunciation comprises a significant part of the communication process since mispronunciation leads to misunderstanding or communication breakdowns (Pennington & Rogerson-Revell, 2019). Notwithstanding its importance, pronunciation is ignored in language teaching settings (Baker, 2014; Darcy, 2018) and underrepresented in textbooks (Nikolić, 2018). A wide array of reasons was cited for the absence of pronunciation in language education contexts such as teachers’ lack of knowledge (Baker, 2014), time constraints (Gilbert, 2008), or various beliefs of teachers (Couper, 2017; Zarzycki, 2020). By analyzing the textbooks in the Turkish educational setting, it is intended to reveal whether one reason for ignoring pronunciation is due to textbook treatment or not. In other words, if there is enough representation of pronunciation in the textbooks, it might be thought that the negligence of pronunciation in Turkish primary and secondary education might not be because of textbook coverage but other reasons. According to the EF EPI 2020 report, Turkey ranks 69th with a score of 465, which places it among the countries with low proficiency (B1 in CEFR). Given the disinterest in pronunciation in Turkish primary and secondary education (Batdı & Elaldı, 2016; İnceçay, 2012; İyitoğlu & Alcı, 2015), this study is worth being conducted so that it hopefully eliminates one of the reasons for ignoring pronunciation within the education context.

Aim and scope of the study

This study aimed to analyze the English textbooks taught in Turkish primary and secondary education with regard to their inclusion of pronunciation features. It intended to outline the representation of pronunciation in the textbooks published by the Turkish Ministry of National Education. The scope is limited to the treatment of pronunciation in the ministerial English textbooks utilized in Turkish primary and secondary schools.

Pronunciation instruction in the research context

Despite its unique geopolitical location connecting Asia and Europe, along with the policy innovations and curricular shifts to improve of language education (Kırkgöz, 2007), Turkey has to go some to cultivate proficient language speakers in a broad sense and language speakers with good pronunciation in a narrow sense. When the Turkish primary education curriculum is examined, it is seen that listening and speaking are the primary focus from second to eighth grades, with the addition of reading and writing as the secondary focus in the seventh and eighth grades (Ministry of National Education, 2018a) and no specific reference to pronunciation even in the suggested tasks and activities. Previous research supports this observation, suggesting a subsidiary role for pronunciation (İnceçay, 2012; İyitoglu & Alcı, 2015). The curriculum for secondary education, on the other hand, includes limited pronunciation practice from ninth to twelfth grades (Ministry of National Education, 2018b). Just by looking at the contents of the two curricula, it might be argued that Turkish EFL learners are introduced to pronunciation in the ninth grade for the first time. Early scholarly work in secondary education confirms this, implying the inadequacy of attention attached to pronunciation (Batdı & Elaldı, 2016; Ustacı & Ok, 2014). Given the inadequate incorporation of pronunciation in the related curricula, a different scenario might not be assumed within language classrooms where the actual teaching occurs. Similarly, it can be hypothesized that EFL textbooks instructed in Turkish primary and secondary schools might fail to include a sufficient amount of pronunciation practice.

Research Questions

The following research questions were formulated in congruence with the research objectives:

RQ (1): Which pronunciation feature is more common in the analyzed textbooks: Segmentals or suprasegmentals?

RQ (2): What segmental and suprasegmental features are included in the textbooks?

RQ (3): According to Celce-Murcia et al.’s (2010) communicative framework of teaching pronunciation, what kind of pronunciation activities are present in the textbooks?

Textbooks in Language Education

Part of the language education curriculum uses supplementary material (Brown, 1995). It can therefore be argued that these materials play a crucial role in language education. Textbooks are among the first to come to mind as far as teaching materials are concerned (Henderson et al., 2012). The design of textbooks that are in line with the curriculum hence bears significance. The activities included in the textbooks should be congruent with the learning outcomes. Ideal materials, according to Tomlinson (2012), should be “informative, instructional, experiential, eliciting, and exploratory” (p.143). Considering that textbooks inform both learners and teachers about the language structures, they should guide learners to practice the language, supply them with the experience of authentic language, encourage them to use the language and help them make discoveries in the language (Tomlinson, 2012), it can be argued that EFL textbooks meet these criteria to varying extents.

Textbooks have always been considered to have an essential place in language education (Richards, 2015). They can be regarded as reference books for many teachers, especially the novice (Richards, 2001) because they provide a structure and program (Molværsmyr, 2017). It would otherwise be demanding and challenging for teachers to prepare a language program on their own. Another advantage provided by textbooks is that they provide standardized instruction (Richards, 2001). Given that language classrooms might contain learners of different proficiency levels and linguistic backgrounds, this aspect of textbooks seems utilitarian. Since teaching also encompasses assessment, it can be argued that textbooks also assist with the standardization of assessment.

Additionally, textbooks are prepared by a team of experts; therefore, it might be stated that they include quality materials (Choi & Tsang, 2020) since these materials are exposed to certain trial and testing. Furthermore, recent textbooks include not only hardcover books, but also other components such as digital learning materials, which might be said to contribute to the variety of learning (Matkin, 2009). Last but not least, textbooks help teachers save time considering the several aspects of a language lesson (Ulla, 2019).

Nevertheless, textbooks have certain limitations. The major criticism addressed towards textbooks is their inclusion of inauthentic language (Richards, 2001). The critics argue that the actual language differs from the one taught in textbooks. However, this should be considered within the context of instructed language, and this downside can be remediated by employing other teaching materials because textbooks are not the sole teaching materials. Another criticism made for textbooks is that they are likely to “deskill teachers’ professional knowledge” (Chien & Young, 2007, p.156) since they limit teachers’ ability to contribute to the teaching process. It must however be noted here that teachers might determine the extent to which textbooks are utilized, and certain modifications might always be made in teaching practices. The last disadvantage of textbooks is that they might not consider learners’ needs (Richards, 2001). Given that textbooks are published for international markets (Richards, 2015), this concern might be alleviated by designing textbooks that address learners’ needs locally.

Despite certain concerns over textbooks, it is safe to say that they continue to “…survive and prosper primarily because they are the most convenient means of providing the structure that the teaching-learning system - particularly the system in change - requires” (Hutchinson & Torres, 1994, p.317).

Method

Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative content analysis (QCA) design to address the research questions. Content analysis “is a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, 2004, p.18). It is a scientific instrument providing researchers with new insights and an increased understanding of phenomena (Krippendorff, 2004). QCA, as the name suggests, is a type of content analysis whereby various texts such as aural, visual, and textual are exposed to systematic categorization and quantification process to make inferences (Coe & Scacco, 2017). It includes text segmentation (unitizing), selection of suitable units for analysis (sampling), consistent coding by different researchers (reliability), and adequate representation of the determined phenomenon by way of a coding scheme (validity) (Coe & Scacco, 2017).

Instruments

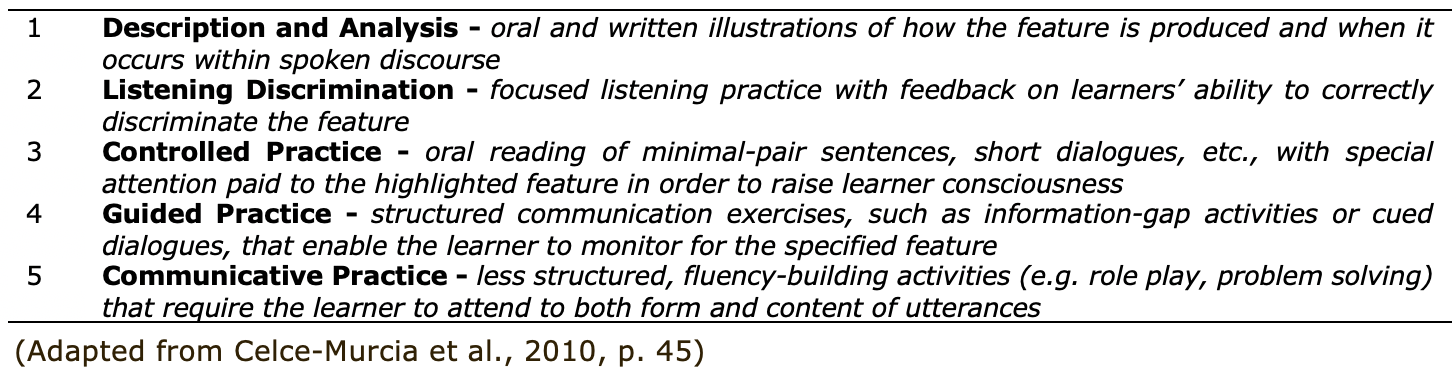

Data required for this research were collected from the analysis of eleven English textbooks written by Turkish authors and published by the Turkish Ministry of National Education. These textbooks have been used for five years starting from the 2018 - 2019 academic year, with the decision of the Ministry of National Education Board of Education and Discipline, dated 28 May, 2018, and numbered 78. Eleven textbooks correspond to second-twelfth grades. Further information can be found in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Information on the analyzed textbooks

Data Collection and Analysis

The eleven EFL textbooks for second through twelfth grades in the Turkish education setting were analyzed quantitatively in terms of content. More specifically, the pronunciation activities in the textbooks were identified and quantified. For the first research question, the collected and documented pronunciation activities were grouped as segmentals and suprasegmentals. For the second research question, which requires an in-depth analysis, specific segmental and suprasegmental features available in the textbooks were reported. For the third and final research question, the documented pronunciation activities were grouped according to the communicative framework for teaching pronunciation (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). To do this, the instructions in the pronunciation activities were closely examined in regard to the framework components.

To illustrate, a typical instruction for the Description and Analysis (D&A) component was “Notice the pronunciation of…”, whereby learners are asked to draw their attention to the target structure. For the Listening Discrimination (LD) component, the sample instruction was “Listen and tick the correct sounds you hear”, wherein learners are asked to differentiate between the target sounds. A model instruction for Controlled Practice (ConP) component was “Read …. and then try reading it faster” which asks learners to practice the target feature. The typical instruction for Guided Practice (GP) was “Make requests using … Practice … through them” that asked learners to practice using the provided model. The instruction for Communicative Practice (CP) was “Work in pairs and make conversations with your friends as in the example. Be careful about intonation issues in asking and answering questions” which asked learners to practice using the target structure in their speech. The gathered data were transferred to Microsoft Excel 2013 and put to descriptive analysis.

Findings and Discussion

RQ (1): Which pronunciation feature is more common in the analyzed textbooks: Segmentals or suprasegmentals?

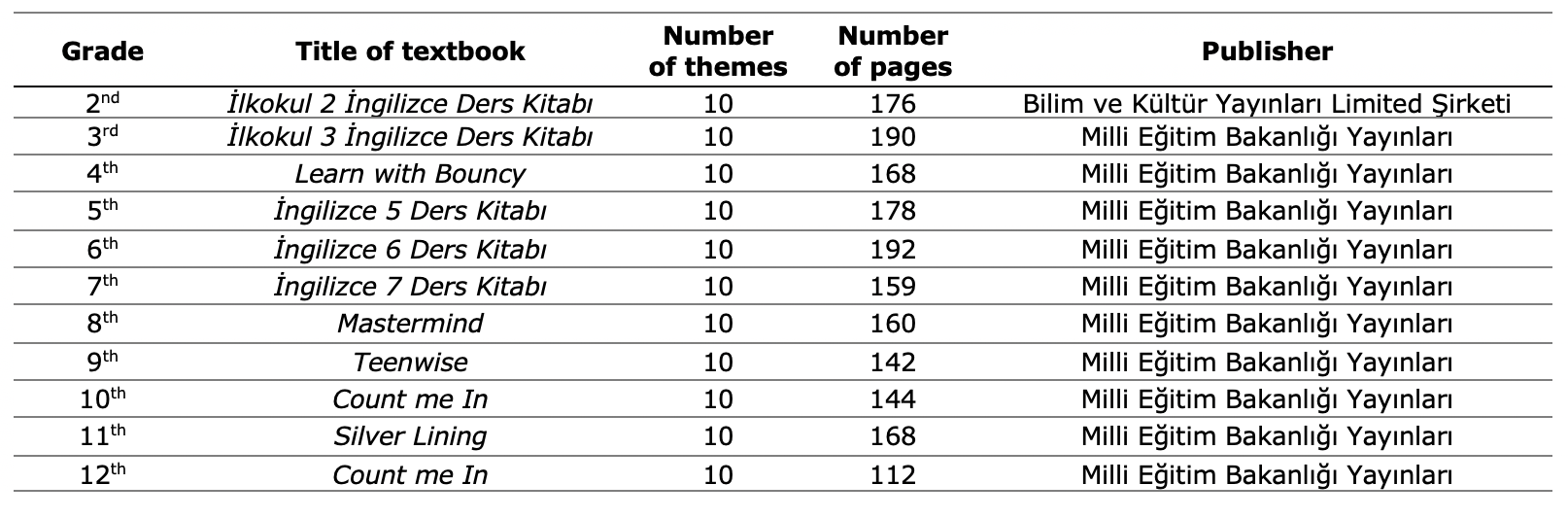

Following a QCA, a total of 90 pronunciation activities were found in the eleven textbooks examined. Suprasegmental activities (f=60) were more common in the textbooks in comparison to segmentals (f=30). Tergujeff (2015) found similar results, indicating that suprasegmentals (i.e., word stress) were more prevalent in the six textbooks examined in his Finnish context. In the current analysis no activities in either pronunciation feature were encountered in the second, third, fourth, sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. It was observed that the pronunciation activities emerged from the ninth grade onward. Except for the one suprasegmental activity present in the fifth grade, the distribution of activities by pronunciation feature and grade was as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Pronunciation features across the grades

It can also be seen in Figure 1 that, as mentioned before, the pronunciation activities concentrated between the ninth and twelfth grades, implying that pronunciation was disregarded in primary education, a logical situation if the primary education curriculum, as previously discussed, also excludes pronunciation or pays no specific attention to this skill. The finding that pronunciation was ignored in primary education textbooks might also have implications. To start with, primary education is the level where young learners receive their first educational experience, and young learners have certain advantages when learning pronunciation due to the plasticity of their brains (Snow & Hoefnagel-Höhle, 1977). It can be easier to train their ears to recognize correct pronunciation (Edelenbos & Kubanek, 2009). It might also be asserted that young learners have a lower language ego, which makes them less sensitive about making mistakes in the target language (Berzonsky, 1990). They, therefore, perceive and try out new sounds easily (Eskenazi, 1999). Considering these potential benefits, it might be argued that textbooks as the primary teaching resource (Richards, 2015) should include at least awareness-raising activities about pronunciation in line with the learners’ age and needs.

The fact that suprasegmentals outnumber segmentals in the EFL textbooks is consistent with previous research. Henderson and Jarosz (2014) examined the textbooks taught in French and Polish secondary schools and found that more than 70% of the activities in the textbooks in both countries were about prosodic features. However, the study conducted by Derwing et al. (2012) revealed differences both across and within the textbook series regarding the treatment of pronunciation. Regarding which pronunciation feature bears more significance, there is no consensus in the literature (Wang, 2020). Some scholars advocate the prioritization of segmentals (Saito, 2011), whereas others endorse suprasegmentals (Kang, 2010) with their significance for intelligibility and effective communication. Therefore, it can be maintained that textbooks, regardless of the pronunciation feature, should present adequate pronunciation activities in keeping with learners’ needs and local contexts.

RQ (2): What segmental and suprasegmental features are included in the textbooks?

Further analysis revealed that a total of thirty segmental features were available in the ninth (f=14), tenth (f=10), and eleventh (f=6) grades, with no segmental activities in the twelfth grade. The distribution of segmental features by grade can be seen in Table 2 below.

Table 2: The distribution of segmental features across grades

The segmental features were centered in the textbooks from ninth to eleventh grades. As Table 2 illustrates, certain features such as /t/ - /θ/, /w/-/v/ sounds, and the pronunciation of –ed ending are repeated among the grades. When the related literature is examined, it is seen that the segmentals present in textbooks were problematic for Turkish EFL learners: /ı/, /i:/, /θ/, /ŋ/, /w/, /v/, /ð/, plural –s, and regular past tense ending (Bardakçı, 2015; Demirezen, 2005; Hişmanoğlu & Hişmanoğlu, 2011; Kılıçkaya, 2011; Mahzoun & Han, 2019). In this sense, it is plausible to say that the choice of segmentals was correct. However, it should be reiterated that segmentals are only available in the textbooks for ninth to eleventh graders given their difficulty (Mahzoun & Han, 2019) and significance of the aspect of intelligibility (Saito, 2011). In addition to the problematic sounds, certain problematic words were also included in the tenth-grade textbook. When carefully examined, it can be seen that these words also include the problematic sounds (e.g., tongue /ŋ/ and examine /ɪ/). In particular, the preference for these might be due to their widespread mispronunciation among Turkish EFL learners.

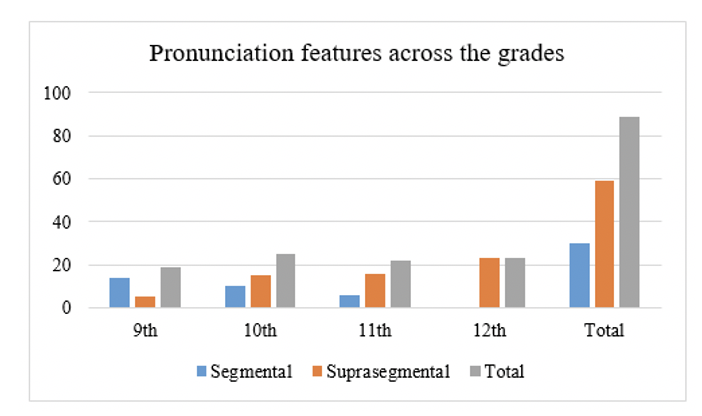

As for the suprasegmental features, it was found that intonation (f=25), connected speech (f=23), and word/sentence stress (f=12) were the predominant suprasegmental features in the secondary school textbooks. The distribution of these features by grades can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: The distribution of suprasegmentals across the textbook grades

A close analysis demonstrated that the intonation activity found in the fifth grade asked learners to pay attention to the intonation of the sentences about the places the speakers in the recording wanted to go. In the tenth grade, the intonation exercises were about Wh- and Yes/No questions, statement questions, short answers, questions tags and direct address (f=2), rising/falling intonation in sentences (f=2), rising/falling intonation in advice structures (f=3), rising/falling intonation in Wh- questions, statements, Yes/No answers, Yes/No questions, and statement questions (f=3), and intonation in comparatives/superlatives (f=2), while the connected speech activities were about the contraction of would (f=3). The distribution of the activities in the eleventh grade by topic was as follows: rising/falling intonation in statements (f=2), and rising/falling intonation in questions (f=2) in intonation, and contraction of auxiliaries in positive/negative sentences (f=4), contraction of had/would (f=2), contraction in past modals (f=1), weak forms of was/were (f=2), and elision/assimilation (f=3) in connected speech. In the textbook for twelfth grades, the pronunciation activities were distributed by intonation in lists, choices, conditional sentences, at the end of statements, invitations, requesting information (f=2), intonation in choices, lists, and conditional sentences (f=2), intonation in questions, statements, listing things, feelings, and contrasting things (f=2); word stress (f=6), sentence stress (f=6); contraction of will/will not (f=2) and yod coalescence (f=3).

It is plausible to assert that the number of pronunciation activities does not suffice given that only 60 suprasegmental activities were available in five textbooks and no activities in either pronunciation feature were present in primary school textbooks (except one activity in the fifth grade). However, it must be noted that textbooks from ninth to twelfth grades included pronunciation activities in each unit/theme. As for the suprasegmental features available in the textbooks, it can be said that the problematic features were chosen for Turkish EFL learners. This claim can be based on the fact that Turkish is not a tonic language (Şenel, 2006), therefore Turkish EFL learners might have problems with suprasegmental features such as stress and intonation. In the literature, these pronunciation features were shown to cause problems for Turkish teachers of English (Demirezen, 2008, 2009, 2012, 2015). Since language teachers in Turkey receive the same primary and secondary education as other learners, it is safe to say that the pronunciation problems of Turkish EFL learners persist. To this end, more pronunciation activities including both features should be integrated into EFL textbooks instructed in the Turkish primary and secondary education contexts.

RQ (3): According to Celce-Murcia et al.’s (2010) communicative framework of teaching pronunciation, what kind of pronunciation activities are present in the textbooks?

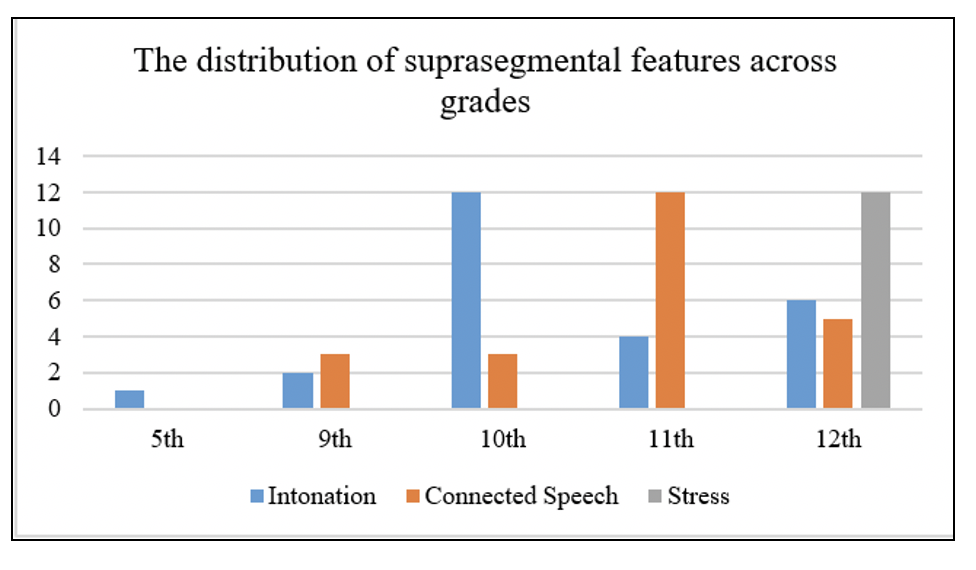

To answer the third research question, the communicative framework for teaching English pronunciation (Table 3) proposed by Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) was utilized.

Table 3: A communicative framework for teaching English pronunciation

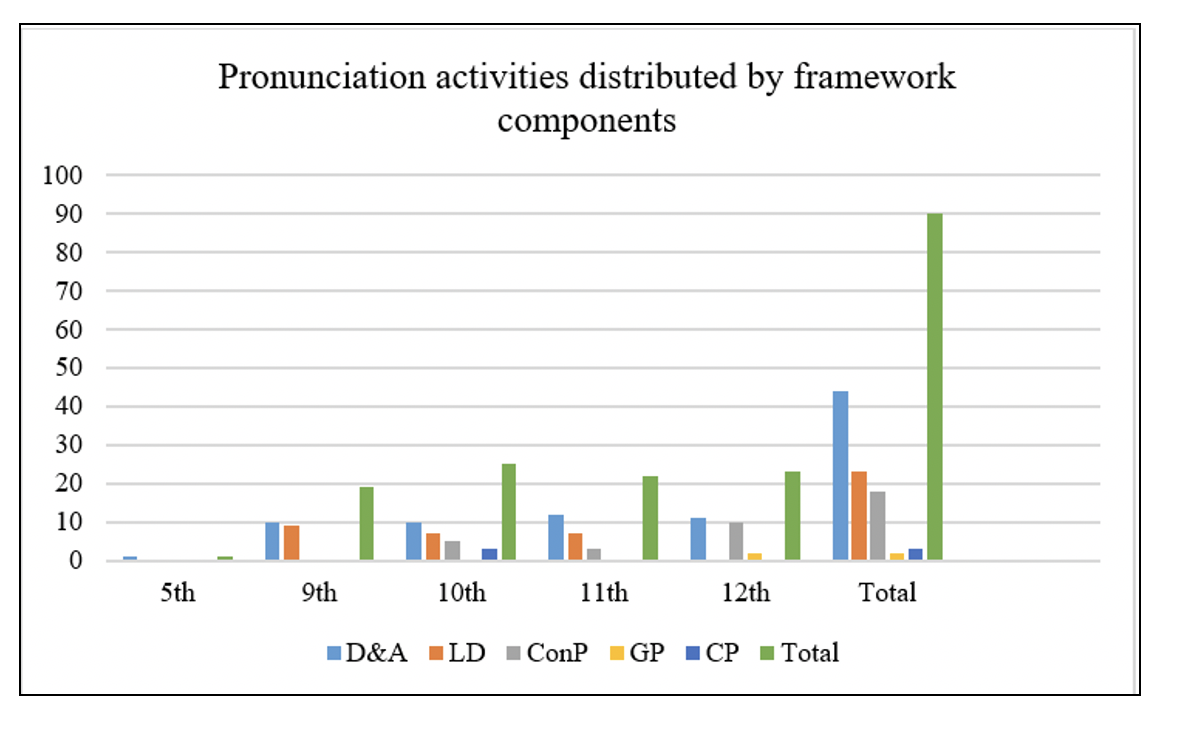

This research-based framework moves from controlled to autonomous activities in five phases. The first phase includes pronunciation activities aiming to describe and analyze the target features through charts and diagrams or explain the rules. The second phase contains activities about focused listening whereby learners are asked to identify or choose between the correct target structure. The third phase involves “repetition practice and oral reading – especially of minimal pair words or sentences or short dialogues” (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010, p. 47). Guided practice is “cued dialogues, simple information-gap exercises, and sequencing tasks such as strip stories” (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010, p.47). The last phase incorporates “storytelling, role play, interviews, debate, values clarification, and problem-solving” (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010, p.47). The distribution of these activities according to the framework was illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: The distribution of pronunciation activities by framework components and grades

The prevailing category in pronunciation activities was D&A (48.89%), followed consecutively by LD (25.56%) and ConP (20%). The GP consisted of 2.22%, while CP comprised 3.33% of the activities. To interpret differently, the majority of the pronunciation activities asked learners to notice the target features (D&A), entailed focused listening wherein learners were asked to determine or differentiate between the target features (LD), and tended to train them to consciously monitor their output (ConP). Given the quantities in Figure 3, it might be argued that the textbooks fall behind the objective of providing learners with the materials to achieve communicative competence. Therefore, the pronunciation activities in the textbooks were not communicative therefore leaving learners unable to attain thorough oral proficiency, considering the significance of pronunciation in communication (Pennington & Rogerson-Revell, 2019). With such pronunciation exercises available only in secondary school textbooks, it is safe to say that learners might only develop an awareness of the target pronunciation features, but fail to attain phonological competence. The study conducted by Ustacı and Ok (2014) supports this, arguing that the language education system in Turkish high schools was overly focused on grammar, reading, and vocabulary with limited exposure to written and spoken communication, which might lead to poor vocabulary and pronunciation.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the eleven EFL textbooks instructed in Turkish primary and secondary schools. The analysis findings revealed that suprasegmental pronunciation activities (66.67%) outnumbered segmental ones (33.33%). It was also discovered that the segmentals included problematic sounds and words for Turkish learners, while the suprasegmentals centered around intonation, connected speech, and word/sentence stress. It was further observed that most of the pronunciation activities pertained to the D&A, LD, and ConP categories of Celce-Murcia et al.’s (2010) framework, implying that they were not communicative. This finding contradicts the curricula, which aim at language proficiency and communicative competence (Ministry of National Education, 2018a, 2018b). One of the significant findings was that pronunciation is excluded in primary school textbooks, except for the only one suprasegmental activity in the fifth-grade textbook. The other activities were distributed proportionately among ninth-twelfth grades.

The findings revealed two implications. First, the EFL textbooks taught in primary and secondary schools in Turkey should be revised to provide more communicative pronunciation activities. Second, language teachers should take on more responsibility and develop learner-specific and extra pronunciation materials to satisfy learners’ needs. This might be expected of language teachers in that they need to be equipped with content and pedagogical content knowledge (Brinton, 2014; Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). In the related literature, pronunciation is ignored for several reasons, such as teachers’ lack of confidence and knowledge (Baker, 2014) and its underrepresentation in textbooks (Nikolić, 2018). In this sense, this study confirmed that pronunciation is underrepresented in primary and secondary school textbooks in Turkey. Future studies might deal with the knowledge base of language teachers concerning pronunciation instruction.

References

Baker, A. (2014). Exploring teachers’ knowledge of second language pronunciation techniques: Teacher cognitions, observed classroom practices, and student perceptions. TESOL Quarterly, 48(1), 136-163. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.99

Bardakçı, M. (2015). Turkish EFL pre-service teachers' pronunciation problems. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(16), 2370-2378. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2396

Batdı, V., & Elaldı, Ş. (2016). Analysis of high school English curriculum materials through Rasch measurement model and Maxqda. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(4), 1325-1347. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.4.0290

Berzonsky, M. D. (1990). Self-construction over the life-span: A process perspective on identity formation. In G. J. Neimeyer & R. A. Neimeyer (Eds.), Advances in personal construct psychology: A research annual, Vol.1. (pp. 155-186). JAI Press.

Brinton, D. (2014). Epilogue to the myths: Best practices for teachers. In L. Grant (Ed.), Pronunciation myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching (pp. 235-242). University of Michigan Press.

Brown, J. D. (1995). Elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development.. Heinle and Heinle.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., Goodwin, J. M., & Griner, B. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide (2nded.). Cambridge University Press.

Chien, C. Y., & Young, K. (2007). The centrality of textbooks in teachers' work: perceptions and use of textbooks in a Hong Kong primary school. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 16(2), 155-163.

Choi, H. M. F., & Tsang, E. Y. M. (2020). Using custom textbooks as distance learning materials: A pilot study in the OUHK. In K. C. Li, E. Y. M. Tsang, & B. T. M. Wong W.(Eds.), Innovating education in technology-supported environments (pp. 163-173). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6591-5_12

Coe, K., & Scacco, J. M. (2017). Content analysis, quantitative. In J. Matthes (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods, (pp.1-11). Wiley.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Couper, G. (2017). Teacher cognition of pronunciation teaching: Teachers' concerns and issues. TESOL Quarterly, 51(4), 820-843. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.354

Darcy, I. (2018). Powerful and effective pronunciation instruction: How can we achieve it?. CATESOL Journal, 30(1), 13-45. http://www.catesoljournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CJ30.1_darcy.pdf

Demirezen, M. (2005). Rehabilitating a fossilized pronunciation error: The /v/ and /w/ contrast by using the audio-articulation method in teacher training in Turkey. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi, 1(2), 183-192. Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jlls/issue/9922/122818

Demirezen, M. (2008). Faulty intonation of nonnative language teachers requiring further education. In Ö. Demirel & A.M. Sünbül (Eds.), Further education in the Balkan countries (pp.1285-1294). Balkan Society for Pedagogy and Education.

Demirezen, M. (2009). An analysis of the problem-causing elements of intonation for Turkish teachers of English. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 2776-2781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.492

Demirezen, M. (2012). Demonstration of problems of lexical stress on the pronunciation Turkish English teachers and teacher trainees by computer. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3011-3016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.606

Demirezen, M. (2015). The perception of primary stress in initially extended simple sentences: A demonstration by computer in foreign language teacher training. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 1115-1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.136

Derwing, T. M., Diepenbroek, L. G., & Foote, J. A. (2012). How well do general-skills ESL textbooks address pronunciation?. TESL Canada Journal, 30(1), 22-44. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v30i1.1124

Edelenbos, P. & Kubanek, A. (2009). Early foreign language learning: Published research, good practice and main principles. In M. Nikolov (Ed.), The age factor and early language learning (pp. 39–58). Mouton de Gruyter.

Eskenazi, M. (1999). Using a computer in foreign language pronunciation training: What advantages?. CALICO Journal, 16(3), 447-469. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24147852

Gilbert, J. B. (2008). Teaching pronunciation using the prosody pyramid. Cambridge University.

Harsch, C. (2017). Proficiency. ELT Journal, 71(2), 250-253. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw067

Henderson, A., Frost, D., Tergujeff, E., Kautzsch, A., Murphy, D., Kirkova-Naskova, A., Waniek Klimczak, E., Levey, D., Cunningham, U. & Curnick, L. (2012). The English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey: Selected results. Research in Language, 10(1), 5–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478%2Fv10015-011-0047-4

Henderson, A., & Jarosz, A. (2014). Desperately seeking a communicative approach: English pronunciation in a sample of French and Polish secondary school textbooks. Research in Language, 12(3), 261-278. https://doi.org/10.2478/rela-2014-0015

Hişmanoğlu, M., & Hişmanoğlu, S. (2011). Internet-based pronunciation teaching: An innovative route toward rehabilitating Turkish EFL learners’ articulation problems. European Journal of Educational Studies, 3(1), 23-36.

Hutchinson, T., & Torres, E. (1994). The textbook as agent of change. ELT Journal, 48(4), 315–328. Retrieved 23.8.2021, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.476.1187&rep=rep1&type=pdf

İnceçay, G. (2012). Turkey’s foreign language policy at primary level: Challenges in practice. ELT Research Journal, 1(1), 53-62.

İyitoğlu, O., & Alcı, B. (2015). A qualitative research on 2nd grade teachers’ opinions about 2nd grade English language teaching curriculum. Elementary Education Online, 14(2), 682-696. https://dx.doi.org/10.17051/io.2015.73998

Kang, O. (2010). Relative salience of suprasegmental features on judgments of L2 comprehensibility and accentedness. System, 38(2), 301-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2010.01.005

Kılıçkaya, F. (2011). Improving pronunciation via accent reduction and text-to-speech software. In M. Levy., F. Blin, C. B. Siskin, O. Takeuchi (Eds.), WorldCALL: International perspectives on computer-assisted language learning, (pp. 85-96). Routledge.

King, C. J. H. (2010). An analysis of misconceptions in science textbooks: Earth science in England and Wales. International Journal of Science Education, 32(5), 565-601. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902721681

Kırkgöz, Y. (2007). English language teaching in Turkey: Policy changes and their implementations. RELC Journal, 38(2), 216-228. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033688207079696

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

Li, X. (2021). Textbook digitization: A case study of English textbooks in China. English Language Teaching, 14(4), 34-42. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v14n4p34

Mahzoun, Z., & Han, T. (2019). The effects of consonant phonemes’ position across the word on pronunciation errors: An empirical study of Turkish EFL learners. The Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 19(2), 48-57. http://www.readingmatrix.com/files/21-632icisq.pdf

Matkin, G. M. (2009). Open learning: What do open textbooks tell us about the revolution in education? University of California. https://cshe.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/publications/2009_open_learning_what_do_open_textbooks_tell_us_about_the_revolution_in_education_.pdf

Ministry of National Education (2018a). İngilizce dersi öğretim programı (ilkokul ve ortaokul 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ve 8. sınıflar) [English language curriculum for primary and secondary education (grades 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8].https://mufredat.meb.gov.tr/ProgramDetay.aspx?PID=327

Ministry of National Education (2018b). İngilizce dersi öğretim programı (9, 10, 11 ve 12. sınıflar) [English language curriculum (grades 9, 10, 11, and 12)]. https://mufredat.meb.gov.tr/ProgramDetay.aspx?PID=342

Molværsmyr, T. (2017). Teachers textbook use in English. Newly qualified teachers’ use of textbooks in planning and execution of English lessons [Unpublished master's thesis]. The Arctic University of Norway. https://hdl.handle.net/10037/11554

Nikolić, D. (2018). Empirical analysis of intonation activities in EFL student’s books. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 7(3), 181-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.3p.181

Pennington, M. C., & Rogerson-Revell, P. (2019). English pronunciation teaching and research. Palgrave Macmillan.

Richards, J. C. (2001). The role of textbooks in a language program. Professor Jack C. Richards: The official website of educator Jack C. Richards. https://www.professorjackrichards.com/wp-content/uploads/role-of-textbooks.pdf

Richards, J. C. (2015). Key issues in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Saito, K. (2011). Identifying problematic segmental features to acquire comprehensible pronunciation in EFL settings: The case of Japanese learners of English. RELC Journal 42(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033688211420275

Şenel, M. (2006). Suggestions for beautifying the pronunciation of EFL learners in Turkey. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 2(1), 111-125. https://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/27/29

Snow, C. E., & Hoefnagel-Höhle, M. (1977). Age differences in the pronunciation of foreign sounds. Language and Speech, 20(4), 357-365. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002383097702000407

Tergujeff, E. (2015). Good servants but poor masters: On the important role of textbooks in teaching English pronunciation. In E. Waniek-Klimczak & M. Pawlak (Eds.), Teaching and researching the pronunciation of English: Studies in honour of Włodzimierz Sobkowiak (pp. 107-117). Springer.

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143-179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

Ulla, M. B. (2019). Western-published ELT textbooks: Teacher perceptions and use in Thai classrooms. Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(3), 970-977. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.3.13.970

Ustacı, H., & Ok, S. (2014). Preferences of ELT learners in the correction of oral vocabulary and pronunciation errors. Higher Education Studies, 4(2), 29-41. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v4n2p29

Wang, X. (2020). Segmental versus suprasegmental: Which one is more important to teach?. RELC Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033688220925926

Zarzycki, Ł. (2020). Omani ESL learners’ perception of their pronunciation needs. Beyond Philology, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.26881/bp.2020.1.04