Introduction

For a long time, second language (L2) learning programs were aimed at improving linguistic competence as well as learning the structure of the language (Brown, 1994). Yet, in recent decades there has been a shift regarding the aim of English instruction. Language learning programs have distanced themselves from the mastery of structure, focusing instead on the ability to use language. With communicative competence in the 1970s, language teachers and educators have emphasized the communication aspect of teaching English. The goal of language learning is now set as "enabling people with different languages and cultural backgrounds to have authentic communication" (MacIntyre et al., 2002, p. 559).

In the view of MacIntyre (2007), the purpose of learning an L2 is to acquire linguistic competence, i.e., the ability to use the language in order to achieve communicative purposes. In the same vein, MacIntyre et al. (2002) describe language learning as a process whereby one can engage in authentic communication with people of disparate linguistic and cultural backgrounds. A look at the recent research (e.g., Ahmed Mahdi, 2014; Aliakbari et al., 2016; Bergil, 2016; Fahim & Dhamotharan, 2016; Öz et al., 2015; Rahbar et al., 2016; Valadi et al., 2015; Yousefi & Kasaian, 2014) reveals that students who have a high willingness to communicate (WTC) are more likely to benefit from the learning opportunities of a communicative approach and to remain more engaged in learning activities inside and beyond the classrooms than those with low WTC.

The widespread adoption of communicative approaches regarding L2 pedagogy indicates the importance attached to developing communicative competence in L2 learners (Green, 2000). In addition, “the theoretical perspectives and pedagogical developments in the current decade are in keeping primarily with the important role of using language for the purpose of communicating in L2 learning and teaching” (Gol et al., 2014; p. 136). Today it is believed that L2 learning is achieved due to the interactive meaningful communication in a pragmatic setting (Swain & Lapkin, 2002). Swain (2000) asserts that language use and language learning unfold simultaneously. Thus, the role of input- and output-based activities in language teaching and their associations with WTC cannot be overlooked.

All these attempts to shift the focus to meaning and communicative approaches to language teaching should affect the language input and output because the only way language can be taught is through input delivery and output practice (Toro et al., 2019). The theoretical developments in second language teaching require that input and output be meaningful and communicatively oriented. Since the 1980s, researchers including Krashen (1985) and Swain (1985) have dealt with the notions of meaning-focused output (MFO) and meaning-focused input (MFI). Krashen is known for his input hypothesis that states that L2 acquisition occurs thanks to sufficient exposure to comprehensible input. Swain proposed her output hypothesis, which is related to the active (productive) dimensions of language, asserting that to ignore speaking and writing as L2 language production forms would render the information passive. In the same vein, Nation and Newton (2009) maintained that an effective language program should include equivalent quantities of MFI (acquisition of language through comprehensible reading and listening input) and MFO (learning language through spoken and written output).

According to Krashen (1985), comprehensible input is the primary determinant of success in second language acquisition (SLA), while others argue that input is not enough because input processing differs from output processing in language acquisition (e.g., Liu, 2015; Reinders, 2012). Imagining that they affect SLA differently, the question is to what extent input and output affect WTC. Therefore, this study is an attempt to scrutinize the role of MFI and MFO activities on English as a foreign language (EFL) learners’ WTC and their perception of these activities.

Literature Review

The role of input and output in language learning

The linguistic input and its nature in L2 acquisition have always been controversial issues in the field of second language acquisition (Ghafouri & Masoomi, 2016). From a cognitive perspective, input accessibility is a prerequisite to developing language (Loewen & Inceoglu, 2016). Evidence shows that linguistic data supplied by input permits acquisition to occur (Gass, 1997). This emphasis on input is one of the theoretical improvements in SLA (Gass, 1997; Long, 1996). Based on the linguistic data obtained from L2 learners, input is a key variable in L2 development (Rahmani, 2016). Language learners do not use all the input that they encounter, so research has focused on the role of attention, which is a vital part of language learning (Leow, 2001; Schmidt, 1993; Smith, 1993; Tomlin & Villa, 1994). Schmidt (2001) stated that without a doubt, attention is essential in all parts of L2 learning.

However, Swain (as cited in Song & Suh, 2008) found that the failure of native-like accuracy and fluency in French immersion programs was not due to lack of input alone, as input is not sufficient for SLA. What is required is comprehensible output along with comprehensible input for automatization and accuracy of L2. From the time Schmidt (1990), in his Noticing Hypothesis, proposed that noticing is a necessary condition for the conversion process of input into intake, many researchers (e.g., Doughty, 2001; Gass, 1997; Skehan, 1998) have investigated the effects of noticing and have reported that noticing linguistic forms is necessary for the learning of phonology, vocabulary, and grammar. Schmidt (1990) maintained that input needs to be noticed by the learners so that it is learned by them.

Output can be produced through either speaking or writing, and it can push the learners to produce and attend to the linguistic features of the language (Benati, 2005). Meanwhile, negotiation of meaning and hypothesis testing may take place during the process of language production (Toth, 2006). Johnson and Johnson (2003) believe that output and interaction and paying attention to the features of both input and output are all indispensable, interrelated components of the process of language learning. Input provides the material for interaction, which can help perceived input convert into comprehended input; hence it integrates the input into the interlanguage system. Meanwhile, interaction occurs during the process of language production with an interlocutor.

Output itself is a kind of input, which provides chances for interaction. Interaction is considered an essential element in communicative language teaching. According to the interaction hypothesis (Long, 1996), the reason that interaction facilitates language learning is because the negotiation of meaning involved in an interaction connects input, noticing, and the learners’ mental capacity. In the interaction hypothesis, the study of interactions between native and non-native speakers suggests that negotiation of meaning, especially in a work context, facilitates language acquisition (Varonis & Gass, 1985). Not only does it require native speakers or more competent interlocutors to make interactional adjustments, but it also links input, learners’ internal capacities, e.g., selective attention, and output in productive ways (Long, 1996).

Zarei et al. (2016) examined the impact of form-focused and meaning-focused input-oriented and output-oriented instruction on vocabulary comprehension and recall, focusing on elementary Iranian EFL learners in a quasi-experimental study. The results revealed that meaning-focused tasks were more effective than form-focused tasks. Azari Noughabi (2017) investigated productive vocabulary learning via meaning-focused listening input, both quantitatively and qualitatively. The quantitative results showed the effectiveness of MFI and MFO instructions employed in the research on the experimental group; however, it qualitatively displayed that such type of instruction is unfeasible because of time limitations and the teachers’ insufficient vocabulary size. Rouhani et al., (2017) examined the impact of input versus collaborative output tasks on Iranian EFL learners’ grammatical accuracy and WTC. Their investigation evinced the positive effects of both tasks on grammatical accuracy; however, the impact of MFO was more than MFI.

Namaziandost et al. (2019) studied the effects of both output- and input-based activities on productive knowledge of vocabulary. The study showed that the two experimental groups outperformed their control counterpart on both post-test and delayed post-tests. Noroozi and Siyyari (2019) examined MFI and MFO modality in relation to its effectiveness on active and passive vocabulary learning and revealed a positive and significant effect on these two modes of vocabulary learning. Furthermore, MFI and MFO were not significantly different in terms of their effects on active and passive vocabulary learning. However, they did not investigate the participants’ perception towards MFO and MFI.

The above shows that input and output are both important in the process of second language learning; however, they should be meaning oriented. Within the theoretical framework of communicative language teaching, the goal of language learning is communication and meaning, and any language activity should assist the learners in moving closer to the given goal. The terms MFI and MFO have been adopted in the current study to help language learners focus on the communicative sides of input and output.

Willingness to communicate

The construct of WTC (Willingness to Communicate) was initially introduced by McCroskey in the communication-studies literature and first language (L1) use (McCroskey & Baer, 1985; McCroskey & Richmond, 1987). Whether or not a person is inclined to speak depends on several variables that pertain to the specific situation (Katsaris, 2019). According to Katsaris (2019), the factors may be the individual’s momentary feelings, perceptions about the interlocutor, and the interlocutor’s preferences, which show that willingness to speak may be affected by features of the situation. However, people have a general willingness to communicate orally (McCroskey, 1997). Such a personality trait was called WTC by McCroskey and Baer (1985). WTC was defined as “an individual’s predisposition to initiate communication with others” (McCroskey, 1997, p. 7). This definition of L1 WTC is constant among situations and people and resulted from such constructs as Unwillingness to Communicate (Burgoon, 1976), Predisposition toward Verbal Behaviour (Mortensen et al., 1977), and Shyness (McCroskey & Richmond, 1982).

According to MacIntyre and Doucette (2010), willingness to communicate can be interpreted as the willingness to use the L2 at a particular time in a dialogue with a specific person and the last psychological step in initiating L2 communication. To create a WTC context, the teacher needs to consider variables associated with the construct, including motivation (Kang, 2005), learner involvement (Walsh, 2002), and an anxiety-free learning environment(Aydin & Zengin, 2008). Learners’ WTC depends on how motivated learners are in foreign-language learning and how much they feel safe and relaxed in the language learning environment.

Motivation is considered a well-established and studied variable contributing to students’ learning and is regarded the beginning reasons of success or failure in any enterprise. Dörnyei (2009) held that a high significance is attached to this psychological construct which can lead to success and failure in the learning process. Motivation is a construct which has been discussed in human behavior and education in particular (Breslawski, 2011). It is, from the Piagetian perspective, an inner force which may lead to developing mental structures (Azizi, 2015). Researchers contend that motivation cannot be examined in isolation but should be studied in a broader dynamic system (e.g., Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2009; Dörnyei, 2009; Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). Dörnyei and associates developed a model named the L2 motivational self-system (Dörnyei, 2009; Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005).

The model maintains that learners decide on how to act according to their ideal self. They spend much more effort on this if they are professional L2 users. Multiple taxonomies of motivation have been suggested by established scholars in this field (e.g., Dörnyei, 2001; McDonough, 2007; Oxford & Shearin, 1994). In the view of Dörnyei (2001), most researchers claim that motivation by definition is concerned with the orientation and magnitude of human behavior as manifested in the following three items: the reasons behind people’s decision to do something, the duration of their willingness to sustain the activity, and how seriously they are going to follow it. Motivation in the words of Kang (2005) is a significant contributor to WTC in L2 learning situations.

Activities conducted in the course of the L2 classroom play a major role in enhancing students’ participation in communication. Bloom (1976) conducted a study to investigate the relationship between learners' engagement and their L2 achievements. The results showed a positive relationship between the two variables. Likewise, Walsh (2002) maintains that involving learners in classroom communication prepares them for real communication situations.

To be successful, L2 learners need a stress-free, low-anxiety classroom climate. Anxiety is another factor researched in the quest to determine what prevents some L2 students from performing acceptably while studying a L2 (Aydin & Zengin, 2008; Brown, 2007b). Anxiety, as Horwitz (1986) contends, is an individual-specific feeling of tension, fear, and agitation, originating in the nervous system.

The impact of anxiety on students’ WTC has been investigated by researchers such as Yashima (2002), who showed that anxiety can considerably influence students’ WTC (Mohammad Hosseinpur & Bagheri Nevisi, 2017; Manipuspika, 2018). Reviewing the variables influencing the degree of WTC leads us to the notion of shyness as described in MacIntyre et al.’s (1998) WTC model as a persistent factor influencing one’s WTC. Accordingly, Chu (2008) investigated shyness and EFL learning in Taiwan, with the results showing a positive correlation between shyness and EFL classroom anxiety. This resulted in a lower degree of WTC among EFL learners.

By reviewing the literature on the notion of anxiety in L2 classrooms and its relationship with WTC, it can be said that providing the students with a stress-free atmosphere in the classroom plays an important role in enhancing learners’ WTC. Bukhari et al. (2015) sought to examine Pakistani undergraduate students’ perceptions of WTC across four contexts and three types of interlocutors. Their WTC was found to be partially high when they were with friends rather than strangers, and they initiated communication in private rather than in public. In a mixed-methods study, Ghahari and Piruznejad (2016) examined the impact of recast and explicit feedback on grammar uptake and WTC among young language learners. Their study showed the positive effect of recast on grammar uptake in the quantitative phase, but WTC was higher for the implicit feedback condition in both the quantitative and qualitative phases. Al Amrani (2019) investigated Omani EFL learners’ perceptions toward their WTC in English. The results showed the learners’ low WTC in English and variations of this personality factor (shyness) depending on the interlocutor and the context. Sarani and Malmir (2019) studied the effect of language teaching using the Dogme method on L2 speaking and WTC among different proficiency levels of learners and revealed that the method had a high impact on advanced learners’ speaking and WTC. Marashi and Eghtedar (2021) scrutinized the impact of flipped classroom instruction of EFL learners’ motivation and WTC. The study revealed that the instruction had a positive effect on motivation and WTC.

Although the literature is replete with studies on MFI and MFO, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, none of the previous studies has explored the comparative effect of MFI and MFO instruction on EFL learners’ WTC, which is the focus of the current study. Since experimental designs in social sciences have their own pitfalls, the researchers also probed the perceptions of the participants towards the efficacy of MFI and MFO activities for developing their WTC. Therefore, the following research questions were addressed:

- Is there any significant difference between the effect of meaning-focused input and meaning-focused output on the WTC of Iranian EFL learners?

- What are the EFL learners' perceptions towards the efficacy of meaning-focused input and meaning-focused output activities for developing their WTC?

Methodology

Participants

The original pool of the current study was 97 intermediate female EFL learners. Having taken the Oxford Placement Test (OPT), 70 participants meeting the criterion of being intermediate formed the final pool of the study. The participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 34, their first language was Persian, and they were studying English at an English language institute in Tehran, Iran

Instrumentation

Oxford Placement Test

To make sure that participants were homogeneous in terms of their L2 proficiency, they took the OPT, which is a flexible test constructed by Oxford University Press and Cambridge ESOL. It was also a convenient method to assign the participants to a specific level of proficiency (Hill & Taylor, 2004). Its administration is easy, quick, and ideal to place students in an appropriate level. The test, which is a multiple-choice format, requires roughly 30 minutes to give, and it can be corrected with the overlay provided. Those participants who scored from 28 to 47 were deemed intermediate and were selected for the study sample. Hamidi et al., (in press) asserted that the test enjoys high reliability (α = .87) based on Cronbach’s alpha. Its construct validity is reported to be high as well (Motallebzadeh & Nematizadeh, 2011; Wistner et al., 2009).

Willingness to Communicate Questionnaire

A Willingness to Communicate in the Classroom Questionnaire, developed by MacIntyre et al. (2001), was adopted to measure the participants’ WTC (in L2). The questionnaire was originally developed to gauge the WTC of immersion students and consists of items targeting all four language skills (speaking: 8 items, listening: 5 items, writing: 8 items, and reading: 6 items). In this regard, it provided a comprehensive picture of both receptive and productive aspects of communication and was deemed appropriate for the purpose of the present study. The questionnaire consists of 27 Likert-type items ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). To make sure of the reliability of the questionnaire, it was piloted on 30 learners having similar characteristics to the participants. The reliability estimate using Cronbach’s alpha turned out to be .87, which shows an acceptable index.

Semi-structured interviews

As a means of collecting qualitative data, open-ended interview questions can be used to gain in-depth insight into participants' perceptions towards a specific topic (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Therefore, to seek out the learners’ perceptions towards the efficacy of MFI and MFO activities for developing their WTC, five participants in each group were selected randomly for an interview. The nature of the interview questions, the participants' availability, and the qualitative analysis of the collected data led the researchers to select five participants randomly in each group for an interview. They were explained the difference between MFO and MFI in Farsi, their mother-tongue. The participants were interviewed face-to-face and individually; the following five questions were asked about the efficacy of MFI and MFO activities in terms of their contribution to WTC:

- Do you think that meaning-focused input/output has made you more motivated to communicate through English?

- Do you think that meaning-focused input/output has made you more interested and willing to communicate through English?

- Do you prefer meaning-focused input/output or regular English instruction?

- Do you think that through meaning-focused input/output you are more engaged and involved in the language teaching exercises and activities?

- Did meaning-focused input/output make you less anxious for speaking English?

All the interviews were recorded using a cellphone. Analysis of the interviews was done on the transcription of the recorded interviews by focusing on how MFI and MFO made participants less anxious and willing to communicate and if they preferred such types of instruction.

Data collection procedure

Twenty participants whose characteristics bore resemblance to the target group were piloted on the OPT. Ninety-nine participants forming the original pool took the OPT to ensure homogeneity, based upon which 70 participants were chosen in terms of their intermediate level of proficiency. Those who obtained a score ranging from 28 to 47 were deemed intermediate, based on the rubric provided by OPT (1-17 Beginner, 18-27 Elementary, 28-36 Lower intermediate, 28-47 Intermediate, 37-47 Upper intermediate, 48-55 Advanced, 56-60 Very advanced). These participants were randomly divided into two equal groups of 35. Next, both groups were given the WTC questionnaire as the pretest.

The first experimental group of the study received MFO in line with Swain’s (1985) output hypothesis. Relying on Swain’s output hypothesis, the activities should lead to producing the language under instruction and if language learners do not produce enough output, the intake will soon turn into passive knowledge such that it will not be readily accessible. To this aim, the participants in this experimental group were exposed to a reading text for five to six minutes each session and were asked to present a summary in spoken form of the text based on the notes they could take during the reading. The reading passages were about nursing homes, at an intermediate level, and between 250 and 300 words. They were also asked to put aside the written text they had read so that they could present a summary on their own.

In experimental group II, the MFI group, the reading activities were carried out in a receptive input mode. To do so, the learners were asked to read the same texts, but they were required to answer some reading comprehension and true/false questions. The MFO/MFI treatment consisted of ten sessions and at the end, the learners in both groups were given the WTC questionnaire as the post-test. Five participants in each group were interviewed regarding their perceptions towards the efficacy of the MFI and MFO instruction.

Data analysis

The quantitative data collected from the WTC questionnaire was analyzed using ANCOVA to answer the first question of the study. To do so, first the assumptions of normality of data and homogeneity of variances were tested. To investigate the second question, the interview data was analyzed through inductive analysis. In this data-driven analysis, the researchers started from data and main themes were identified, categorized and coded. Coder reliability was also checked by the two authors, who analyzed the data and ensured the identification of the themes in the data.

Results

The effects of MFI and MFO on WTC

The statistical test of ANCOVA was used to compare the effects of MFI and MFO on participants’ WTC. Since ANCOVA requires that data be normally distributed, relationship between dependent and covariate variables be linear, regression slopes be homogeneous and variances be equal, first these assumptions were tested. After ensuring ANCOVA assumptions, the main output of ANCOVA was consulted to find the answer to the first research question.

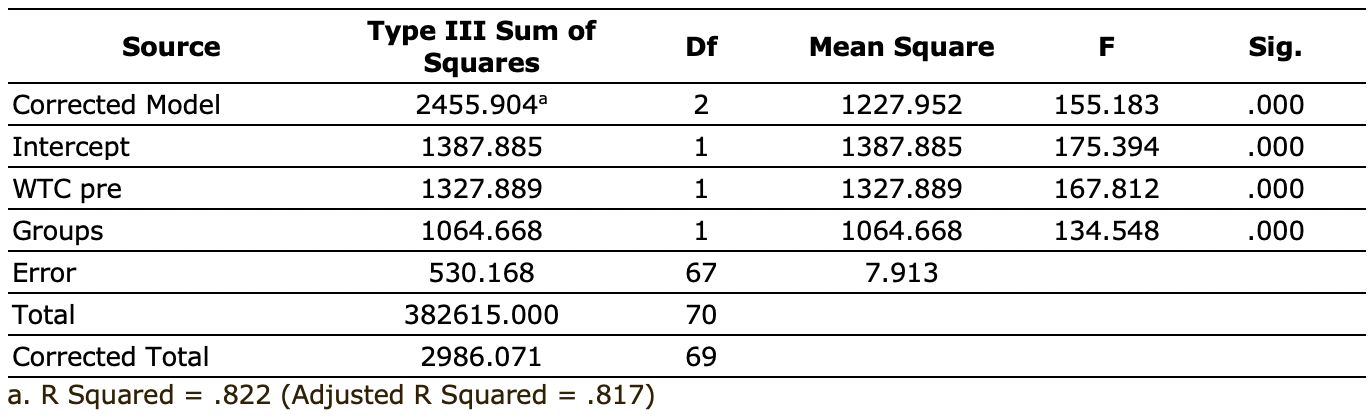

Table 1: The results of ANCOVA on WTC pretest and posttest

The result of ANCOVA showed there was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of WTC scores (F=134.54, P=0.00). This means that one of the methods (MFO vs. MFI) was more effective. To understand which method was more effective, the estimated marginal means were compared between the two methods.

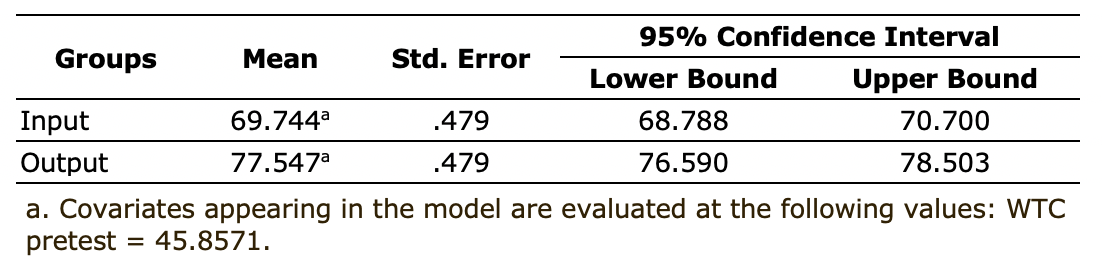

Table 2: Estimated marginal for each group

As seen in Table 2, the mean score of the MFO group was larger than the MFI group. Accordingly, the MFO had a significantly better effect on the WTC of the learners.

Perceptions towards MFI and MFO

The second research question was about students’ perceptions towards the efficacy of MFO and MFI in enhancing their WTC. The interview data were analyzed using inductive analysis (Creswell & Creswell, 2018), in which broad themes were identified and then generalizations were made based on the themes. Based on the analysis of the students’ answers to the interview questions, it was revealed that students found MFO more effective than MFI in developing their WTC. This efficacy was reflected in WTC, motivation, preference, and the anxiety-free effect of MFO. For instance, respondents reported that meaning-focused output affected their oral competence and made them more confident, but the same did not hold true for MFI as evidenced by their interview responses.

MFO made me put my self-confidence into my learning procedure while my learning is through speaking. (Excerpt 1, Student 1)

When I read the text, I got familiar with the topic and could speak confidently because I found information through reading the text. (Excerpt 2, Student 1)

To me, MFI was simply reading a text and marking the statements as true/false. Therefore, it did not play a role in my speaking so that I might get confident. (Excerpt 3, Student 2)

As I was not allowed to speak in MFI, it did not flourish my confidence to express myself through speaking. (Excerpt 4, Student 3)

Additionally, they mentioned that MFO made them more motivated; between MFI instruction and MFO one, interviewees preferred MFO (90 %). The students’ perception was in line with results of the quantitative part of the study, which showed there was a significant difference between MFO and MFI.

After reading the text in MFO, I was planning to organize the content in my mind to summarize and this way interested me. (Excerpt 5, Student 7)

As my peers in MFO were sometimes commenting on my ideas to neatly express the content made me interested to speak because they helped me both in grammatical mistakes and content organization. (Excerpt 6, Student 8)

The teaching practice in MFI did not motivate me because no communication occurred in this teaching activity. (Excerpt 7, Student 9)

MFI was not motivating for me because it looked like the regular instruction we have already been taught. (Excerpt 8, Student 9)

Basically, the interview questions targeted students’ opinions about the motivational aspect of MFO and MFI, their effectiveness, and students’ preferences for one of the two methods. They also addressed the engagement factor and anxiety factor of the two methods.

Excerpt 9, Student 5

MFO engaged me both in reading the text to take notes and giving summary orally. Besides, I was anxious during giving summary because making mistakes would occur.

Excerpt 10, Student 1

In MFO, I used to take notes while reading the texts and it made me engaged because I needed to pay attention to the meaning of the texts and writing on a piece of paper. I was anxious while speaking because I feared to make mistakes.

What really immersed me was MFO allowing me to give lecture which could strengthen my speaking skill but the only thing made me worry was making mistakes throughout talking; however, it can be a good practice for further steps. I mean giving lecture in larger contexts. (Excerpt 11, Student 2)

MFO motivated me to talk using the vocabularies in the texts and it alleviated my anxiety to some extent because the efforts of searching for words in my mind was reduced; however, it engaged me well because I needed to fully understand the passage. (Excerpt 12, Student 3)

We used to read a text in MFI and mark a statement as true or false. It engaged me while reading plus I got anxious because my chance of response was 50-50; that is, the answer would be either right or wrong. (Excerpt 13, Student 1)

MFI engaged me when reading the texts because it made me attend to the meaning to answer the questions. The anxiety was at the level of answering the question in which I had no other chance but right or wrong. (Excerpt 14, Student 1)

Reading the texts between the line really involved me to heed to the details because I needed to choose an option which was either true or false and this worried me much. (Excerpt 15, Student 3)

The only positive point of MFI was that it reduced my anxiety to some extent but not to a large extent because it was easy to answer the questions following the texts through scanning; however, this practice was energy consuming. (Excerpt 16, Student 5)

With regard to the motivational aspect of MFO and MFI, the identified themes revealed that 80% believed that the MFO enhanced their motivation to communicate in English language compared to 30% believing in MFI. This percentage was found through counting the themes in the data. Students in the output group felt more interested and eager to learn English and be able to communicate through English. Students were also more positive about the effectiveness of the MFO than the MFI. Eighty-five percent of the learners were positive about the MFO while 25% were positive about the MFI. Regarding students’ preferences, students in the MFO group highly preferred MFO (90%) compared to students in the input group (23%) preferring MFI. The MFO group mentioned that they would like to continue with MFO instead of receiving conventional language instruction (90 %).

One of the factors that was indicating students’ interest in MFO instruction was that of engagement. Students (70% in output and 31% in the input group) felt that they were more engaged with language learning activities. In other words, the output group felt less boredom and tiredness while in the classroom. Finally, 82% of the students in the MFO group expressed that they were more comfortable with the instruction in comparison to the MFI group students in comparison to the MFI group,27% of whom felt comfort with the instruction.

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the possible differences between the effect of meaning-focused output (MFO) and meaning-focused input (MFI) on Iranian EFL learners' willingness to communicate (WTC). Moreover, the study aimed at exploring the EFL learners' perceptions towards the efficacy of MFO and MFI activities for developing their WTC. The results of statistical analysis indicated that the MFO group outperformed the MFI group in terms of WTC scores. The content analysis of the interviews revealed that students receiving MFO were more positive toward this strand in enhancing WTC than those receiving MFI. Such positive perceptions were reflected in motivational, effectiveness, preference, engagement, and anxiety-reduction aspects of MFO.

The current study has congruity with the previous studies into WTC (Roohani et al., 2017). Based on the findings of the current study, MFO was more effective in terms of its contribution to WTC. The results are justified on the grounds that since Output Hypothesis is concerned with language production (Swain, 1996), in this study only output-based activities were found to enhance the WTC of the learners. Since learners in the MFO group were involved with language production and WTC is also concerned with productive language, the WTC of the learners improved as a result of receiving output-based activities. This study parallels Zarei et al., (2016) who found that MFO was more effective for vocabulary recall than MFI. However, the results of the present study indicated some inconsistencies with this study because their research found that the efficacy of MFI was more for vocabulary comprehension. Nor do the findings of this study support those obtained by Azari Noughabi (2017) that revealed learners’ productive vocabulary size was affected by MFI.

Swain (1996) affirmed that learners should be provided with an opportunity to produce language if they are to acquire and use the language effectively with low anxiety. Swain further noted that output can assist learners in noticing gaps and weaknesses in their linguistic knowledge, which would cause better language production and thus help learners use the language more smoothly. The rationale behind the superiority of MFO over MFI might be its nature. MFO deepens the understanding of learners while reading since it engages the cognitive processes both to understand the text and to produce output.

Another significance of the findings of this study is that when it comes to meaning-focused instruction, MFO is more effective for WTC than MFI. That is because learners' output provides learners with a more implicit understanding of the target language. One reason MFO helped in promoting WTC might be participants’ level of proficiency. It lends support to the statement made by McIntyre et al. (1998) that language learners’ proficiency level affects their WTC. McIntyre et. al. (1998) corroborate the effectiveness of attitude and confidence on WTC. Cetinkaya (2005) states that the cause of WTC is the low level of anxiety. Therefore, language learners’ level of proficiency along with affective states should not be neglected.

The study showed the MFO outperformed the MFI on WTC because MFO made the participants active agents and it made them willing to communicate, pushing them to speak more. The level of confidence in MFO group was high, as the participants themselves expressed in the interviews, but they were anxious during the tutorial sessions. The data demonstrated that anxiety was negatively correlated with WTC (e.g., Peng & Woodrow, 2010).

It should also be noted that in the current study, MFO was carried out through summarizing certain passages by the language learners, which might be a challenge in large classrooms. However, the summarizing activity can be practiced in small groups. In this way, summarizing can be done collaboratively by the students and presented to the entire class. Various students can be called by the teacher to summarize parts of a story so that more students have the chance to practice summarizing in a big classroom. Additionally, teachers in the ESL or EFL context can make use of various oral communication activities other than summarizing. However, it is recommended that such oral communication activities be meaning-focused. The goal of such activities needs to be conveying meaning in a message rather than simply practicing grammar and sentence structure.

Conclusion

The results of the study led to the conclusion that MFO may better contribute to the WTC of foreign language learners. Since WTC is associated with the productive modes of communication, MFO may more readily aid the learners in becoming willing to communicate in L2. The findings suggest that input does not provide the adequate condition for proper second-language acquisition.

The current study had some limitations which can be taken into consideration by other future researchers. Due to availability, all participants of the current study were female learners. The same study can be conducted targeting male learners as a sample. Moreover, the participants of this study were intermediate learners within the age range of 19 to 35. Other researchers may be inclined to conduct studies with learners at other proficiency levels and other age ranges. The findings of the present study have implications for language teachers and teacher educators as well as materials developers concerning the important role of output in enhancing WTC. Studies (e.g., De la Fuente, 2006; Izumi, 2002; Song & Suh, 2008) have suggested that the significance of the output role equals that of input in language acquisition. These claims are congruent with Swain’s output hypothesis (Swain, 1985), which gives rise to L2 acquisition. The research on output (e.g., Dekeyser & Sokalski, 1996; De la Fuente, 2006; Izumi, 2002; Song & Suh, 2008) and formal and informal observations of a Canadian immersion program (Swain, 1985) have shown that understanding spoken English is not sufficient for the development of learners’ productive skills and language acquisition and, thus, language teachers are encouraged to employ output activities if they intend to improve learners’ WTC. Moreover, teacher educators can also provide teacher trainees with more awareness concerning the contribution of the output hypothesis to WTC. Materials developers may also incorporate more output-based activities in their work.

The findings of the current study have further implications for teachers and material developers. Teachers should not provide their learners with i+2 input, which is beyond their current level of competence, lest the learners become discouraged due to a lack of comprehension (Brown, 2007a). In this case, they will receive input, but not what Gass (1997) called "apperception." In addition, learners’ WTC will decrease. Material developers can supply English teachers with suggestions and strategies in instructors’ textbook guides for better utilization of MFO and MFI in order to facilitate EFL learners’ output and WTC. In addition to delivering MFI and increasing their L2 production, teachers should be cognizant of EFL learners’ cultural barometers in order to give them input on topics which are appropriate in their own culture. Finally, teacher-education programs can hold workshops aimed at how to increase EFL learners’ WTC via MFO and MFI.

References

Ahmed Mahdi, D. (2014). Willingness to communicate in English: A case study of EFL students at King Khalid University. English Language Teaching, 7(7), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n7p17

Aliakbari, M., Kamangar, M., & Khany, R. (2016). Willingness to communicate in English among Iranian EFL students. English Language Teaching, 9(5), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n5p33

Al Amrani, S. N. A. (2019). Communication and affective variables influencing Omani EFL learners’ willingness to communicate. Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 51-77. https://dx.doi.org/10.22055/rals.2019.14179

Aydın, S., & Zengin, B. (2008). Yabancı dil öğreniminde kaygı: Bir literatür özeti [Anxiety in foreign language learning: A literature review]. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 4(1), 81-94. https://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/58

Azari Noughabi, M. (2017). The effect of meaning-focused listening input on Iranian intermediate EFL learners productive vocabulary size. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(15), 141-149. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1143810.pdf

Azizi, D. B. (2015). The effect of direct oral corrective feedback on speaking accuracy and motivation to speak of Iranian EFL learners [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Khazar Institute of Higher Education.

Benati, A. (2005). The effect of processing instruction, traditional instruction and meaning-output instruction on the acquisition of the English past simple tense. Language Teaching Research, 9, 67-93. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168805lr154oa

Bergil, A. S. (2016). The Iinfluence of willingness to communicate on overall speaking skills among EFL learners. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 232, 177 – 187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.043

Bloom, B. S. (1976). Human characteristics and school learning. McGraw-Hill.

Breslawski, T. (2011). Factors influencing business student motivation in low stakes assessment

exams. American Journal of Educational Studies, 4(1), 61.

Brown, H. D. (1994). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Prentice Hall.

Brown, H. D. (2007a). Principles of language learning and teaching. Pearson.

Brown, H. D. (2007b). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (3rd ed.) Prentice Hall Regents.

Bukhari, S. F., Cheng, X., & Khan, S. A. (2015). Willingness to communicate in English as a second language: A case study of Pakistani undergraduates. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(29), 39-44. https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/26670/27475

Burgoon, J. K. (1976). The unwillingness‐to‐communicate scale: Development and validation. Communications Monographs, 43(1), 60-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757609375916

Cetinkaya, Y. B. (2005). Turkish collage students’ willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Ohio State University. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=osu1133287531&disposition

Chu, H. R. (2008). Shyness and EFL learning in Taiwan: A study of shy and non-shy college students’ use of strategies, foreign language anxiety, motivation, and willingness to communicate [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Texas, Austin. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3864

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The internal structure of language learning motivation and its relationship with language choice and learning effort. The Modern Language Journal, 89(1). 19–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3588549

DeKeyser, R. M., & Sokalski, K. J. (1996). The differential role of comprehension and production practice. Language Learning, 46(4), 613−642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1996.tb01354.x

De la Fuente, M. J. (2006). Classroom L2 vocabulary acquisition: Investigating the role of pedagogical tasks and form-focused instruction. Language Teaching Research, 10(3), 263−295. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168806lr196oa

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second language motivation research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 43-59. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190501000034

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self-system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self, (pp. 1-8). Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identity and L2 self. Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Doughty, C. (2001). Cognitive underpinnings of focus on form. In P. Robinson (Ed.). Cognition and second language instruction. Oxford University Press.

Fahim, A., & Dhamotharan, M. (2016). Willingness to communicate in English among trainee teachers in a Malaysian private university. Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2), 105-112. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2016.105.112

Gass, S. M. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ghafouri, A., & Masoomi, M. (2016). The effect of visual and auditory input enhancement on vocabulary acquisition of Iranian EFL university students. International Journal of English Linguistics, 6(7), 81-86. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v6n7p81

Ghahari, S., & Piruzinejad, M. (2016). Recast and xplicit feedback to young language learners: Impacts on grammar uptake and willingness to communicate. Issues in Language Teaching, 5(2), 187-209. https://dx.doi.org/10.22054/ilt.2017.8058

Gol, M., Zand-Moghadam, A., & Karrabi, M. (2014). The construct of willingness to communicate and its relationship with EFL learners’ perceived verbal and nonverbal teacher immediacy. Issues in Language Teaching, 3(1), 135-160. http://ilt.atu.ac.ir/article_1373.html

Green, S. (2000). New perspectives on teaching and learning modern languages. Multilingual Matters.

Hamidi, H., Azizi, D. B., & Kazemian, M. (in press). The effect of direct oral corrective feedback on motivation to speak and speaking accuracy of Iranian EFL learners. Education and Self Development.

Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. (2004). Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement: Pragmatics and issues. Current directions in psychological science, 13(4), 161-164. http://cdp.sagepub.com/content/13/4/161

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.2307/327317

Izumi, S. (2002). Output, input enhancement, and the noticing hypothesis: An experimental study on ESL relativization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 541–577. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263102004023

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. P. (2003). Joining together: Group theory and group skills. Allyn and Bacon.

Kang, S.-J. (2005). Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System, 33(2), 277-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.10.004

Katsaris, T. (2019). The willingness to communicate (WTC): Origins, significance, and propositions for the L2/FL classroom. Journal of Applied Languages and Linguistics, 3(2), 31-42. https://als-edu.wixsite.com/jall/abstract-katsaris-3-2

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Longman.

Leow, R. P. (2001). Do learners notice enhanced forms while interacting with the L2? An online and offline study of the role of written input enhancement in L2 reading. Hispania, 84(3), 496-509. https://doi.org/10.2307/3657810

Loewen, S., & Inceoglu, S. (2016). The effectiveness of visual input enhancement on the noticing and L2 development of the Spanish past tense. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 89-110. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2016.6.1.5

Liu, D. (2015). A critical review of Krashen’s input hypothesis: Three major arguments. Journal of Education and Human Development, 4(4), 139-146.

Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie, & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–468). Academic Press.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 564-576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00623.x

MacIntyre, P. D., Baker, S. C., Clement, R., & Conrod, S. (2001). Willingness to communicate, social support, and language-learning orientations of immersion students. Studies on Second Language Acquisition, 23(3), 369-388. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263101003035

MacIntyre, P. D., Baker, S. C., Clément, R., & Donovan, L. A. (2002). Sex and age effects on willingness to communicate, anxiety, perceived competence, and L2 motivation among junior high school French immersion students. Language Learning, 52(3), 537-564. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00194

MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545-562. https://doi.org/10.2307/330224

MacIntyre, P. D., & Doucette, J. (2010). Willingness to communicate and action control. System, 38(2), 161-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.12.013

Manipuspika, Y. S. (2018). Correlation between anxiety and willingness to communicate in the Indonesian EFL context. Arab World English Journal, 9(2), 200-217. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol9no2.14

Marashi, H., & Eghtedar, D. (2021). Applying the flipped classroom model to foster motivation and willingness to communicate. Iranian Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(2), 70-89. https://dorl.net/dor/20.1001.1.24763187.2021.10.2.6.2

McCroskey, J. C. (1997). Willingness to communicate, communication apprehension, and self-perceived communication competence: Conceptualizations and perspectives. In J. A. Daly (Ed.). Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension, (pp. 191-216). Hampton.

McCroskey, J. C., & Baer, J. E. (1985). Willingness to communicate and its measurement. [Conference presentation]. Western Speech Association Convention, Tucson, AZ.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1982). Communication apprehension and shyness: Conceptual and operational distinctions. Communication Studies, 33(3), 458-468. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510978209388452

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1987). Willingness to communicate and interpersonal communication. In J. C. McCroskey & J. A. Daly (Eds.), Personality and interpersonal communication (pp.129-159). Sage.

McDonough, S. (2007). Motivation in ELT. ELT Journal, 61(4), 369-379. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm056

Mohammad Hosseinpur, R., & Bagheri Nevisi, R. (2017). Willingness to communicate, learner subjectivity, anxiety, and EFL learners’ pragmatic competence. Applied Research on English Language, 6(3), 219-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.22108/are.2017.78045.0

Motallebzadeh, K., & Nematizadeh, S. (2011). Does gender play a role in the assessment of oral proficiency?. English Language Teaching, 4(4), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n4p165

Mortensen, C. D., Arntson, P. H., & Lustig, M. (1977). The measurement of verbal predispositions: Scale development and application. Human Communication Research, 3(2), 146-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00513.x

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL listening and speaking. Routledge.

Namaziandost, E., Dhkordi, E. S., & Shafiee, S. (2019). Comparing the effectiveness of input-based and output-based activities on productive knowledge of vocabulary among pre-intermediate EFL learners. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 4(2), 2-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-019-0065-7

Noroozi, M., & Siyyari, M. (2019). Meaning-focused output and meaning-focused input: The case of passive and active vocabulary learning. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 6(1), 21-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1651443

Peng, J.-E., & Woodrow, L. (2010). Willingness to communicate in English: A model in the Chinese EFL classroom context. Language Learning, 60(4), 834-876. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x

Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. The Modern Language Journal, 78(1), 12-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02011.x

Öz, H., Demirezen, M., & Pourfeiz, J. (2015). Willingness to communicate of EFL learners in Turkish context. Learning and Individual Differences, 37(3), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.12.009

Rahbar, B., Suzani, M., & Sajadi, Z. (2016). The relationship between emotional intelligence and willingness to communicate among Iranian intermediate EFL learners. Journal of language teaching: Theory and practice, 2(3), 10-17.

Rahmani, A. (2016). Input enhancement through using author’s biography: The impact on Iranian EFL learners’ reading comprehension ability across gender. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 7(2), 370-376. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0702.17

Reinders, H. (2012). Towards a definition of intake in second language acquisition. Applied Research on English Language, 1(2), 15-36.https://dx.doi.org/10.22108/are.2012.15452

Roohani, A., Forootanfar, F., & Hashemian, M. (2017). Effect of input vs. collaborative output tasks on Iranian intermediate EFL learners’ grammatical accuracy and willingness to communicate. Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics, 8(2), 71-92. https://doi.org/10.22055/RALS.2017.13092

Sarani, A., & Malmir, A. (2019) The effect of Dogme language teaching (Dogme ELT) on L2 speaking and willingness to communicate (WTC). Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 11(24). 261-288. https://elt.tabrizu.ac.ir/article_9637.html

Schmidt, R. W. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129-158. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/11.2.129

Schmidt, R. (1993). Awareness and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 206 –226. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190500002476

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3–32). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, M. S. (1993). Input enhancement in instructed SLA: Theoretical bases. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15(2), 165-179. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44487616?seq=1

Song, M.-J., & Suh, B.-R. (2008). The effects of output task types on noticing and learning of the English past counterfactual conditional. System, 36(2), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.09.006

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehension output in its development. In S. M. Gass & C. G. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235-252). Newbury House.

Swain, M. (1996). Integrating language and content in immersion classrooms: Research prospective. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 52(4), 529-548. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.52.4.529

Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97-114). Oxford University Press.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2002). Talking it through: Two French immersion learners’ response to reformulation. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(3-4), 285-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-0355(03)00006-5

Tomlin, R. S., & Villa, V.. (1994). Attention in cognitive science and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 16(2), 183-203. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263100012870

Toro, V., Camacho-Minuche, G., Pinza-Tapia, E., & Paredes, F. (2019). The use of communicative language teaching approach to improve students’ oral skills. English Language Teaching, 12(1), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n1p110

Toth, P. D. (2006). Processing instruction and a role for output in second language acquisition. Language Learning, 56(2), 319-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-8333.2006.00349.x

Valadi, A., Rezaee, A., & Kogani, P. (2015). The relationship between language learners’ willingness to communicate and their oral language proficiency with regard to gender differences. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 4(5), 147-153. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.5p.147

Varonis, E. M., & Gass, S. (1985). Non-native/non-native conversation: A model for negotiation of meaning. Applied Linguistics, 6(1), 71-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/6.1.71

Walsh, S. (2002). Construction or obstruction: teacher talk and learner involvement in the EFL classroom. Language Teaching Research, 6(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168802lr095oa

Wistner, B., Sakai, H., & Abe, M. (2009). An analysis of the Oxford placement test and the Michigan English placement test as L2 proficiency tests. Bulletin of the Faculty of Letters, Hosei University, 58, 33-44

Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. The Modern Language Journal, 86(1), 54-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00136

Yousefi, M., & Kasaian, S. A. (2014). Relationship between willingness to communicate and Iranian EFL learner’s speaking fluency and accuracy. Journal of Advances in English Language Teaching; 2(6), 61-72.

Zarei, A. A., & Moftakhari Rezaie, G. (2016). The effect of task type and task orientation on L2 vocabulary learning. Issues in Language Teaching, 5(2), 255-278. https://doi.org/10.22054/Ilt.2017.8061