Introduction

An introduction of English to primary school students in non-English speaking countries in Asia has made policymakers include it in the national curriculum. This issue has emerged because more children are learning English at their early levels of education today. Some studies reported that English has been taught in primary schools as a compulsory subject in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam as well as three other countries, China, Japan, and Korea (Ching & Lin, 2019; Kirkpatrick & Liddicoat, 2020) using the first language (L1) for language of instruction. Only Singapore, Brunei, and the Philippines adopted English as a medium of instruction from grade one to teach mathematics and science (Kirkpatrick, 2012). Different from other aforementioned countries, the Indonesian government stipulates English as a locally tailored subject (Sulistiyo et al., 2020; Zein, 2017) with flexibility to include it into the school’s curriculum without the government endorsed guidance.

Furthermore, the new educational paradigm in English Language Teaching (ELT) known as English as an International Language (EIL) has given the opportunity to use English as a language of interaction to the speakers of the expanding circle countries in Kachru’s (1985) terms, such as Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia (Bautista & Gonzales, 2006; McKay, 2018). It affirms the feasibility of using the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach to be implemented in the expanding circle countries, including Indonesia. Since its introduction to the national curriculum of Indonesia in the 1950s as a compulsory subject for secondary levels, English has gained students' interest. Furthermore, English lesson has also been popular as a local elective content subject recommended by the curriculum for primary school students aged 7-12 years old since the 1990s. Many schools have started to offer English lessons earlier, as of grade one, although it was advised that the curriculum be implemented in grades four to six (Wahyuni, 2016; Zein, 2017). Therefore, the current 2013 curriculum of Indonesia has highlighted a breakthrough of English as the non-compulsory subject in primary schools for providing a wider arena for its teaching. CLIL is feasible to be implemented in the teaching of English to young learners (TEYL) as an innovative approach because it benefits the learners with higher-order thinking skills and problem-solving ability (Ellison, 2019; Setyaningrum & Purwati, 2020). For a language-oriented objective, soft-CLIL is language-driven as the teacher uses the techniques employed in other subjects like mathematics and science and themes for language teaching. Meanwhile, if the teaching objective is content oriented and English is used as the medium of instruction to teach subjects, hard-CLIL is applied. To date, CLIL refers to teaching one or more subjects through the second language (L2) and may also refer to content-based subjects in language programmes. English is used across the curriculum and as a language of instruction for teaching subjects like mathematics and science in some primary schools in Indonesia (Rohmah, 2019).

Literature Review

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) for young learners

CLIL is not a new pedagogical method in the sense of second language education as well as foreign language teaching and learning. In the mid-1990s, the concept of CLIL was first officially used in Europe (Dobson, 2020). The word CLIL is commonly used in European nations, although it has been adopted far beyond Europe, such as in Asia and South America. A number of theories underpin the implementation of CLIL to young learners (YLs). Based on the pedagogy perspective, CLIL relies on the constructivist and socio-cultural notions as the learning process facilitates YLs to have more meaningful input and output in L2 or target language (Graham et al., 2018). In response to these, CLIL is believed to result in the greater and more flexible opportunities of both content and language learning. Mehisto et al. (2008) claimed that CLIL offers YLs more realistic and natural opportunities to learn and use an additional language to support them to learn the language unintentionally while understanding the content.

For long-term learning objectives, CLIL differs from Content-Based Instruction (CBI) and ESP (English for Specific Purposes) on one hand, and English as Medium of Instructions (EMI) on the other, in that CLIL aims to integrate content and language learning. The dual focus of the CLIL approach emphasizes the equal accomplishment of both language and content learning (Coyle et al., 2010; Mehisto et al., 2008; Meyer, 2011). CLIL provides the learners with broader opportunities to get accustomed to foreign languages as the 'vehicular language' (VL) skills (Divljan, 2012) as well as the relevant material knowledge and skills required for a globalized world since it allows the teachers to get engaged with as many authentic materials as possible. Adequate acceptance of teacher support is deemed crucial to ensure that the students have made gains in proficiency from the input they have received (Meyer, 2011). CLIL also provides an opportunity for students to be engaged in the content. In addition, CLIL is seen as an ideal learning approach with significant potential and effectiveness as it brings some basic tenets of a specific method of task-based learning and communicative language teaching by accommodating the state of authenticity and meaningfulness in communication (Mukminatien et al., 2020).

Further, CLIL provides an opportunity for students to be engaged in the content. Implementing the CLIL approach could result in a significant improvement in the students’ content comprehension. Ouazizi (2016) proved that CLIL increases second graders' mathematical knowledge by using a mathematical test compared to traditional learning. Meanwhile, another content subject (science) was also examined by Huang (2020). Thirty students in one of Taiwanese primary schools were involved in this study. The students joined a science course once a week for three hours. Using several techniques including graphic organizers, self-assessment and students’ test (pre-test and post-test), the research was aimed to examine the effects of students’ science learning in CLIL program. The findings showed that the CLIL approach implemented was successful to enrich the students’ vocabulary size as well as the students’ science knowledge. The more the students learn new science themes, the more knowledge they gain in English. Meanwhile, other studies in higher education also justify that CLIL facilitates students to improve their content learning such as in the Accounting department (Nugroho, 2020), Maritime department (Simbolon, 2020), and Economics (Huzairin et al., 2018). Those studies demonstrate that the CLIL approach not only increases the students’ vocabulary, but also boosts their content knowledge by stimulating their interest in learning other subjects in English.

Teaching young learners is different from teaching adult learners. To conduct efficient learning experiences, teachers should understand the students’ characteristics. Some learners still have limited abilities in reading and writing, even in their first language; they have limited knowledge of the world, but they show excitement and curiosity to learn about the world around them; they love fantasy, imagination, and movement, and they have a short period of focus and attention, so they can easily get bored unless they are interested in the activity (Copland et al., 2014; Nunan, 2018).

When deciding what model of CLIL appropriated to apply with YLs, it is necessary to consider at which level of development they are. However, concerning CLIL specifically, Mehisto (2012) suggested five separate fields that teachers and practitioners should consider: (1) appropriate level of academic achievement of the content subject using CLIL language; (2) appropriate level of functional proficiency in all of the skills, listening, speaking, reading, and writing; (3) appropriate level of first-language competence based on YLs' age; (4) cultural awareness associated with the language used in CLIL and the students' first language; and (5) supporting learning activities for the cognitive and social skills to prepare students in the upcoming era. As a result, teachers need to be aware of what teaching techniques should be used at each level of the production of YLs to ensure optimum success in the teaching and learning process.

Core features of content and CLIL

To implement CLIL approach effectively, Mehisto et al. (2008) proposed six core features including multiple foci, authenticity, active learning, safe learning environment, scaffolding, and cooperation. Firstly, multiple foci define how learning is promoted through cross-curricular themes and projects, with content instruction supporting language use and language instruction. Secondly, authenticity refers to the use of authentic materials, cases, and contents during instructional sessions which means that the teachers would regularly adopt specific facets with respect to the students' lives and interests. Thirdly, active learning indicates that the students have to perform more dominantly than the teachers. In other words, the students should be given greater opportunities to get involved in classroom activities, whilst the teachers partake as facilitators. Fourthly, the safe-learning environment is meant to define diverse strategies used to evoke the students' confidence in the real implementation of language and content usages. Further, scaffolding is termed as various strategies the teachers apply to help the students advance their skill level in the event of creativity and critical thinking establishment. Thus, the students are supposed to get challenged to move forward to the next level of their learning processes. Lastly, co-operation is defined as the attempt of the CLIL teachers to collaborate with other teachers (either a subject teacher or another language teacher), the local community, and other related stakeholders to design their CLIL lessons.

CLIL implemented in an Indonesian EFL context

As CLIL is rapidly becoming an innovative new trend in the field of language teaching, many researchers reported the implementation of CLIL in Europe, the United States, Asian countries, and Latin America (Gallardo-del-Puerto et al., 2020; Lopriore, 2018; Suwannoppharat & Chinokul, 2015). To be specific, in Indonesia, a growing body of research regarding CLIL in various EFL settings have emerged. CLIL has been implemented in all education levels, ranging from primary to higher education. As an example, in Indonesia tertiary education level, some research explores CLIL related to the teaching materials (Sarip et al., 2018), classroom activities (Puspitasari, 2016), the lecturers’ perspective (Arham & Akrab, 2018), and the effectiveness of CLIL to improve the students' English competence (Manafe, 2018). The previous studies provide significant insights into CLIL, yet it was mostly adopted at the higher education level.

Meanwhile, at the secondary education level, several types of research were reported concerning the development of an assessment tool using CLIL approach (Khomsah & Subjantoro, 2019), teaching materials for vocational schools (Setyomurdian & Subyanto, 2018), and teaching materials for math and science fields including biology, chemistry, and physics (Suhandoko, 2019). Further, Izzah et al. (2018) proved that CLIL approach in Islamic junior high school could improve the students’ knowledge of the language and the content (the stories in Al Qur’an). However, only a few research studies were concerned with primary education. One of them was a study conducted by Andriani et al. (2018) which depicted the CLIL implementation in math and science lessons and found five strategies used for promoting autonomous learning in classes. Furthermore, through an exploratory study, CLIL in Indonesia primary school is projected to be a preferable teaching approach for TEYL with the condition that the teachers’ competence is consistently upgraded through a professional development program (Setyaningrum, & Purwati, 2020).

Considering all the aforementioned research, CLIL implementation in Indonesia is mainly explored in higher and secondary education levels. Although the previous studies provoke the feasibility of CLIL in primary schools, the detailed implementation of CLIL is still underexplored, especially in Indonesian primary school context. Hence, to fill the gap, the current research was conducted to analyze the implementation of CLIL approach based on Mehisto et al.’s (2008) core features of CLIL at primary schools in Indonesia. It also aims at exploring and describing the CLIL practices by Indonesian teachers of English to young learners (EYL) in their teaching based on CLIL core features suggested by Mehisto et al. This theoretical basis was chosen as it promises to ensure the quality of learning processes and teaching materials in CLIL classes (Guzmán, 2017; Mehisto, 2012). CLIL is expected to create enriched learning environments in which students can learn both content and language simultaneously. This can be achieved by implementing the six core features of CLIL which are multiple foci, safe and enriching environment, authenticity, active learning scaffolding, and cooperation (Mehisto et al., 2008). To implement effective TEYL activities, a rich CLIL learning environment needs to be further situated in the context of Indonesian EFL classes, especially in primary schools. Finally, this research is not only to present the prevalence of these six features in classroom practices, but also to reflect the teachers’ understanding of core features of CLIL to validate their CLIL practices in their classes.

Method

This section presents the design, participants and context of the study, data collection, and data analysis procedures.

Design

This research was an exploratory study of the implementation of CLIL approach in selected primary schools in East Java, Indonesia. The findings were analyzed based on the framework of CLIL core features by Mehisto (2008). Yin (2018) verified that an exploratory case study is appropriate when the researcher needs a comprehensive and in-depth description of a specific phenomenon. As the aim of the research is to explore CLIL practices in a certain primary school context, this exploratory case study involves a series of efforts to specific practices to be covered by later studies. In this regard, this research focused on CLIL core features practiced by the EYL teachers in teaching three lower grade levels and their understanding of CLIL core features concept reflected from their teaching.

Participants and context

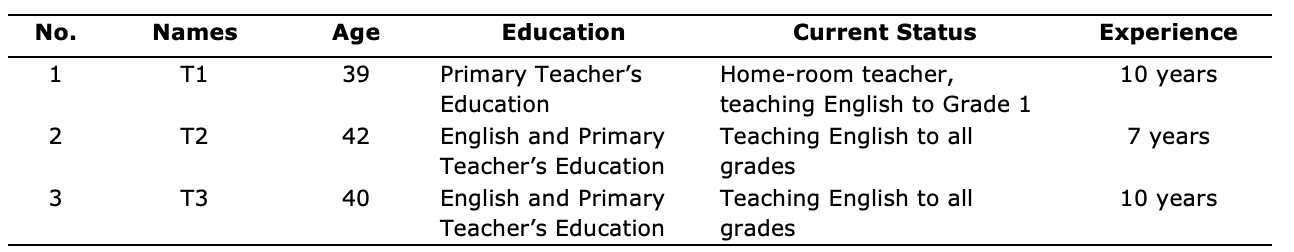

The participants were three teachers at the primary schools practicing CLIL approach in teaching EYL. They gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Fortunately, two participants had been in touch with the researchers because of their attendance in several EYL workshops in which the researchers served as the teacher educators. The third teacher agreed to participate due to her experience in creative EYL teaching – she was also a supervisor of the youth volunteers of a non-government organization teaching English at her school. The three participants met the criteria to be the research participants which were 1) having sufficient experience in teaching English in primary school; 2) having joined several professional development programs in teaching English for Young Learners; and 3) having implemented CLIL approach in their classes. The following is the participants’ background information (see Table 1):

Table 1: Participants’ background information

The researchers asked for permission from the National Unity and Politics Agency (Kesbangpol) of the municipality before conducting the research. Regarding research ethics, the participants were required to read, complete, and sign a consent form indicating that they willingly volunteered their time during the series of research data collection, and also reserved a right to withdraw their participation in any phase of the research.

Data collection and analysis

To explore the CLIL Core Features in primary schools in Indonesian setting, direct observation and in-depth interviews were conducted. The observations were conducted three times during the first semester for each class. The observation was conducted in a combined 90-minute class or 90 minutes each. It took 90 minutes of English lessons of grade 1, grade 2, and grade 3 for each meeting. The teaching and learning process from three selected primary schools' EYL classes were audio-visually recorded and transcribed. The observational field notes were analyzed to gain the emerging themes related to the CLIL core features as suggested by Mehisto et al. (2008). Furthermore, after conducting classroom observations, interviews with the three EYL teachers were conducted. Semi-structured interview was more preferable with eight prepared questions consisting of two themes including (1) the teachers’ prior knowledge about CLIL approach; and (2) CLIL implementation in primary school level. The interview data were analyzed manually. Using deductive coding, two researchers of this study worked together to transcribe and acted as the coders of the interview result. There were eight codes under two themes as it followed the interview questions. To ensure its reliability, the researchers confirmed the result with the research participants. Finally, to justify the findings and to have the teachers’ reflections toward the implementation of CLIL Core Features from the classroom observations and interviews, a questionnaire was distributed. The closed-ended questionnaire consisted of 27 items with six criteria which were adapted from Guzmán (2017) and Mehisto et al. (2008). The emerging themes reached through the analysis were used to consider the conclusions of this research.

Trustworthiness

In qualitative research, trustworthiness is used to assess the quality and usefulness of qualitative studies. It consists of criteria for methodologically competent and ethically sensitive practice. There are some tools to enhance trustworthiness, such as triangulation, member checking, or auditing (Birt et al., 2016; Creswell, 2012; Rallis & Rossman, 2009). Hence, to verify the data, participation validation was employed by returning the observation and interview transcripts to the three participants of this research.

Results and Discussion

Contextual EYL teaching for fun and meaningful learning

As one of the EYL innovations, CLIL was suggested as the approach that can be used in TEYLs contextually (García, 2015; Setyaningrum & Purwati, 2020). CLIL approach can be implemented in EYL context by integrating some themes in a class. The themes cover both content and language learning (Shin & Crandall, 2014). As a result, one of the most crucial CLIL core features presented in a CLIL class is multiple foci. In Indonesia’s recent curriculum, thematic learning referred to integrated learning using themes to link multiple subjects to provide meaningful learning experiences for students (Wardani et al., 2020). This was approved by the result of classroom observation. In T3’s class, the teacher’s initiative in introducing some English words regarding mathematics to get the students accustomed to pronouncing the numbers from 1 to 20 should be planned. Her reflective session to end the instruction by asking the students what they had learned that day and ensuring the relevance of the materials delivered, by counting the number together and singing a song made from the subject under discussion, were multiple foci evidence.

Based on the observations and lesson plan analysis, all teachers (T1, T2, and T3) indicated that their classes and lesson plans include multiple foci because clear connections between various topics and learning are contextualized by the use of the thematic subjects. In the third grade, as an example, the thematic syllabus consists of eight main themes, namely Living Organisms, Loving Plants and Animals, Things around us, Weather, Energy and Their Changes, Technology Development, and Praja Muda Karana (Scouts). These themes allowed the teachers to integrate them into several lessons such as science, math, and English. The themes were connected to the students’ daily lives as well as their immediate environments to increase their learning interest and achievement.

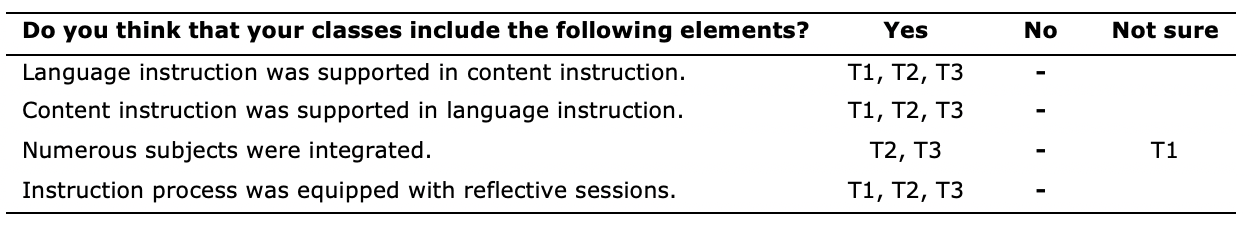

Based on the teachers’ reflection concerning the multiple foci, Table 2 indicates that all teachers basically have sufficient understanding about this core feature. In other words, the teacher claimed that they have integrated both language and content in their classes. The detailed result can be seen in the following table:

Table 2: The teachers’ reflections in relation to multiple foci

In Table 2, T1 was not sure that she could integrate numbers of the subjects into her teaching because of her anxiety about the multiple foci concept. Furthermore, based on the interview result, she explained that she found it as a challenge that there were not enough resources that she received to support her dream of fun English teaching.

What the teachers believed about implementing this core feature was related to their prior knowledge on the existing curriculum and the previous implementation of Indonesian bilingual education (Jayanti & Sujarwo, 2019; Mukminin et al., 2018), in connection to the thematic regular lessons for primary school students (Yulianti, 2015). The result of the interview shows the following data that evidenced the situations:

Yes, it’s right. Based on "Kurikulum 2013," English is not mandated to be taught at primary school but as an extracurricular activity, that teacher should design their materials on their own. In classroom practice, we try to match it based on the theme that the content subject discussed. (T1, researcher translation)

Yes, we previously introduced bilingual education by teaching the students math and Science using English. By the 2013 curriculum implementation, we dismiss the program and occasionally we still use English in certain subjects like math. (T3, researcher translation)

Well, before we design our materials, we have a syllabus that we have decided on previously. After having the theme, then, we design our materials based on the content subject that we are going to teach that is possible to integrate it using English. For example, numbers, we integrate with math. The topic "Our Body", we integrate it with science and many others. (T2, researcher translation)

Enriching the students’ language skills via English language exposure

Repetition is commonly practiced in young learners’ classes. Greetings and farewells were always in English. The English language exposure was exhibited by the teaching in grade 1. During the classroom observation, T1 led the morning prayers in three languages, Arabic, English, and Bahasa Indonesia, while English was used as a classroom language. Yet, she shifted her language into Bahasa Indonesia when the students did not understand her instruction. From the interview, the teacher’s explanation is as follows:

As English is a foreign language for students, they do not have enough exposure to use it. They have a limited number of vocabularies to use in the lesson. To get them familiar with English, I greet them in English, write down the date and day on the blackboard before I start my lesson. So, they unconsciously think about it even though I don't explain the days in English. (T1, researcher translation)

With respect to teaching materials, T1 had fairly integrated the language use and content during the instruction. For example, she attempted to overview prior materials (using English to count from 1 to 20) on the board and had the students pronounce all the numbers loudly. Afterward, the mathematical operation was started. The last merit in regard to authentic materials utility showed that the teacher had fundamentally been trying to supply and deliver some authentic materials, like using real pictures in learning the theme Things around Us before she distributed the worksheets to the students. Further, to build the students’ confidence in using the target language during the class, the teacher initiated some common classroom’s language that students usually need to use to communicate in class. This was supported by the following quote from an interview:

I tried to make my students get used to speaking English in certain circumstances. For example: "May I go to the toilet, please?", "May I ask something?", "May I wash my hands?", "I have finished", and others. My students have understood how to use those expressions. So, they speak in English unconsciously. (T1, researcher translation)

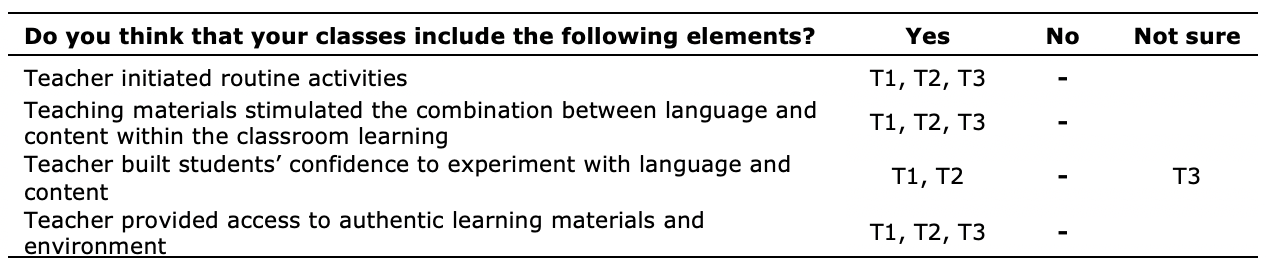

Although the practices showcased in grade one could not be observed in grade two and three, the teachers had ample knowledge about a safe and enriching environment as presented in Table 3:

Table 3: The teachers’ reflections in relation to a safe and enriching environment

Table 3 depicts all teachers’ confirmation about the core feature of a safe and enriching environment in their classes. T1’s responses were related to what she had practiced in the classrooms while T2 was confident about her understanding of the topic. T3 responded similarly with a little doubt about her ability to successfully facilitate learning for their students.

Authentic material development

As English is an extra-curricular subject, the teachers had their arena in developing the materials based on the students’ needs and relate them with the students’ real-life experiences. The teachers should consider media for the learning process such as colorful cards, pictures, and joyful songs which were inserted as a part of instruction to provoke the students' enthusiasm and reduce the tediousness during the process of instruction. Moreover, from the lesson plan analyses, the tasks presented in the worksheets were taken from various sources following the topics, such as textbooks and the internet, especially to meet the need of the contextualization of the materials.

Other classroom observation presented the use of authentic materials. In T1’s class, when the students were learning about body parts, for example, they were asked about healthy lifestyle, healthy food, or daily nutrient intake. However, it was found that T3 rarely practiced activities for solving mathematical real-life problems. As a matter of a fact, Mariño (2014) suggested that real-life problem solving is important to be integrated into math and science classes because it is a very useful subject for real life.

Additionally, T2 accommodated students' interest by initiating the Total Physical Response (TPR) method during the class when the students' language is passive and still emerging. Uztosun (2018) suggested TPR as one of the EYL teacher’s core professional competencies. It is a method that facilitates the students to practice a new language. They can get the experience in using and making meaning of the new language from action rhymes or songs. Hence, this kind of a method can be non-threatening allowing them to be more active and participatory in the learning process. The following rhyme was practiced to learn numbers and family members in grade two classrooms. The rhyme was translated from its version in Bahasa Indonesia.

One and one, I love my mother.

Two and two, I love my father.

Three and three, I love brothers, sisters.

One, two, three, I love my family.

During the interview, T2 declared that authenticity refers to authentic teaching materials. To develop authentic learning materials in the CLIL classroom, the teacher should design the materials based on students' interests, needs, and likes. Coelho (2017) indicated that teaching materials and activities are designed to meet CLIL requirements as they help draw on established prior knowledge, abilities, interests, and experience of the students. Regarding authenticity, based on the lesson plan analyses, T1 and T3 presented authentic teaching recourses for the class that are contextualized and real to support the students’ initial knowledge about the tourism industry as the local potential of the school setting. Further, the teachers’ evaluation regarding authenticity is shown in the following table (Table 4).

Table 4: The teachers’ reflections in relation to authenticity

Table 4 showed various responses to each aspect of authenticity. All of the teachers discerned that they had already facilitated their students with the flexibility of using the languages. It was because they adopted various teaching materials to provide authentic learning for their students. Nonetheless, T2 was not sure about accommodating her students’ learning although she had used the songs containing knowledge about numbers and family members. T2 and T3 were anxious about the authenticity of their lessons if they were connected to the students’ environments. Therefore, it implies that the teachers still need their professional development which contributed to their confidence in including authentic materials for their teaching.

Languages for meaning-making

In the active learning sphere, the teacher was the facilitator who had to provide the students with more opportunities to speak. It was an evidence that the students spoke in three languages, i.e., English, Bahasa Indonesia, and Bahasa Jawa(Javanese Language). For clarification, the students often asked the teacher to use the language that they were confident to use. Based on the classroom observation (for T2 and T3 classes), before presenting the group or pair works, the students’ cooperative works were communicated using Bahasa Indonesia or Javanese language. Furthermore, in presenting their pair or group projects, the teacher stimulated the students to speak in English. As a result, communication among the presenter, the teacher, and the other students was carried out in English with some translation if needed. In addition, the students were perceived to be active in asking and deliberating the project with their members. This was also stated by the teacher (T3) in following interview result:

Ehm ... Uh! Depends on the materials we are talking about. I focus to use English with all students in class. I give them chance to use the language that they prefer to use during group discussions. (T3, researcher translation)

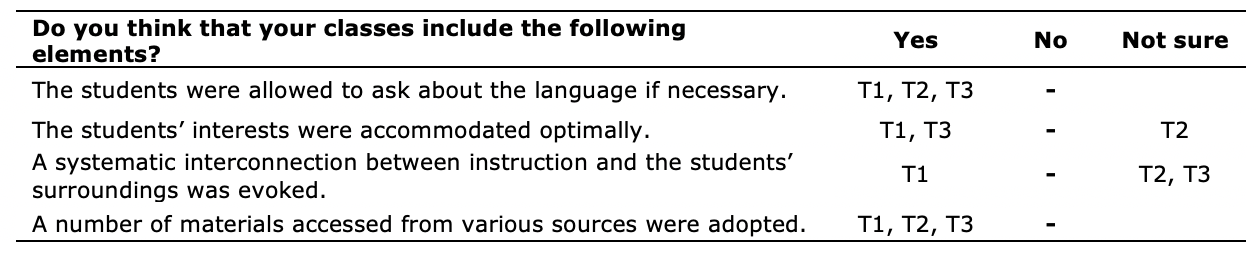

T3 provided flexibility to use the language to make the students active in the learning process. It was also reflected from her answer on the questionnaire although she was not sure about her ability in making progressive evaluations and involving the students in the negotiation process upon the language and content meaning. The following table (Table 5) provides detailed information regarding the teachers’ evaluation about active learning:

Table 5: The teachers’ reflections in relation to active learning

Based on Table 5, all teachers (T1, T2 and T3) considered student-centered learning essential to facilitate an active learning environment in their classes and they believed that they had practiced them. This is to promote students' autonomous learning as suggested by Van Kampen et al. (2018) and Pinner (2013), a feature believed to highly contribute to the success of language learning (Inayati et al., 2021). However, all of them doubted that the students had already got actively involved in the negotiation process upon the language and content meaning. This was because the students still had a lack of vocabulary to use in negotiation using English. They tended to use Bahasa Indonesia or local language in meaning-making. Mehisto (2012) justified that in a CLIL context, learning material will include some of the vocabulary required to do peer-cooperative work, such as terms and sentence sets needed to handle group work, promote critical thinking, and evaluate and examine group work outcomes.

Teachers’ roles for scaffolding

In the scaffolding phase, it was shown that the teacher tried to elicit the students’ prior knowledge related to the teaching materials. Hence, when the teacher explained the materials or topics in English, the students could understand them easily. To exemplify, during the classroom observation, a song entitled One and One, I Love my Mother was set to be performed. The teacher (T3) had made a slight modification in the song, particularly on its rhyme and lyrics as the students were familiar with its version in Bahasa Indonesia. As a result, the students got an easier way of understanding the vocabulary used. Further, she made the students recall their understanding of prior materials before coming at the others. These findings are supported by Gabillon and Ailincai (2013) who affirmed that one of the goals set in the scaffolding sphere is to repackage and simplify information or knowledge in a user-friendly manner and encourage students to take another step forward, not just to the student’s current ability.

Further, in terms of a response to various learning styles, the teacher (T1) stated that the students who required intensive assistance would be seated close to the teacher. They are also put into a group due to the teacher’s finding that some of the students were still in significant need of writing guidance. This is proven by the following interview transcriptions:

Ehm... it depends on the materials we discuss. When I use English, I rarely do it in group work because some of my students still need my help in their basic writing and reading skill. They still have less responsibility in their learning process. (T2, researcher translation)

You can see in my class that I divide my students into two big groups to ease me in a literacy program. Those who need more assistance in reading and writing are placed in the front rows so that I can drop by frequently. I can consistently observe and check their progress. Meanwhile, the students who have better literacy sit behind them. For the first grader, I concentrate on their vocabulary and tend to have individual assignments because of their less responsibility in group work. (T1, researcher translation)

Generally, the teachers (T1, T2 and T3) had a similar idea for scaffolding. They did not do much on group work because of the young learners’ responsibility issue. For T1 and T2, literacy becomes the focus.

As observed in the third-grade classroom, T3 wrote down “numbers” on the whiteboard along with how to write it in English such as one, two, three onwards and twenty, thirty and so forth (It was expected that the students knew the conventional verbal sequence up to at least 20 and were able to use the principles of counting which they have learned for counting up to 100). T3 explained Counting Numbers in detail about how to count the number in ones and tens, and operate all the numbers in math operational addition. She explained the process of how to make twenty-eight in mathematics in Bahasa Indonesia and English, such as It is 20 and 8, to make 28. “dua puluh ditambah delapan, jadi dua puluh delapan”. Moreover, she wrote on the blackboard and then checked the students’ understanding by pointing at some students and asked them to solve the mathematical operations. Overall, all of the teachers agreed that they tried to scaffold their students’ understanding by calling the students’ prior knowledge and using more simple and understandable explanation. They also made some attempts to foster the students’ critical thinking. Further information regarding scaffolding can be seen in the following table (Table 6).

Table 6. The teachers’ responses in relation to scaffolding

According to Table 6, the teachers considered scaffolding in their classes in different ways such as utilizing the students’ prior knowledge, repackaging the content or materials in a more understandable way, and fostering the students’ critical thinking. There were two crucial aspects that the teachers confirmed their doubt in implementing it which were providing more challenging tasks (T1, T2, and T3) and facilitating varied learning styles (T2 and T3). In fact, simplifying the instructions can proceed the students’ comprehension to the next level.

Collaborative learning, collaborations among teachers and stakeholders

Cooperation can be in the form of collaborative learning in class, collaboration among teachers to plan the CLIL lesson, and the involvement of parents and society for a real-world learning experience. Based on the observation, in a class of third graders, T3 often asked students to work in a group. In one of the examples, the teacher asked students to do pair work to create their mathematical problems and calculate them. Meanwhile, T1 rarely divided the first graders into groups because they still enjoyed working individually, yet still had some individual difficulties in learning, particularly in literacy. The following interview result is T1’s explanation about the situation:

…Grouping students in my class is a bit hard since some of my students still need some guidance on how to read and write. Also, they still have less responsibility in their learning process… (T1, researcher translation)

Further, the collaboration among language teachers and subject teachers was considered as a mere administrative task because the regular meeting of KKG- Kelompok Kerja Guru (teacher forum) in the municipality is scheduled once a month. It is only for administrating the textbook and school examinations. The following is the explanation based on the interview with T2:

Each school has its own textbook… That is why we find difficulties to decide the theme or the materials every semester. I join in teacher forum (KKG) to unify my teaching materials. In the forum, the teachers discuss and decide which themes or materials that the students will learn in a year. (T2, researcher translation)

Unfortunately, the data did not provide any explanations regarding the cooperation between the school and the parents. Meanwhile, one of the schools had collaborated with stakeholders for having international exposure from one of the international organizations. This is explained by the teacher (T2) as follows:

From the AIESEC[1] voluntary program of teaching my students at school, I can introduce a new culture attaches to the English language. The international volunteers prefer to have "hi-five", rather than shaking hands as the students usually do to their teachers. I have to talk to those volunteers that they should introduce the cross-cultural understanding in a simple way to my students. They explain about their culture practice some of them with the students. All are happy with this cooperation. (T2, researcher translation)

Related to cooperation, the teachers strongly agreed that they needed a Teacher Professional Development program regarding EYL and CLIL approach. They believed that it would improve their teaching performance as a homeroom teacher who is responsible for teaching both content and language subjects. This was supported by the following interview result with T1:

... Training or workshop about EYL and CLIL would be beneficial for me to better my teaching in general and to improve our teaching of English. (T1, researcher translation)

From the teachers’ explanation, it is clear that cooperation was critical for their teaching. Collaboration among teachers of English and content subject teachers as well as the contributions of the stakeholders were considered meaningful for the CLIL approach for TEYLs. All teachers confirmed that they facilitated their students to work cooperatively although T1 had never cooperated with the other subject teachers while T2 and T3 were not sure about it. Because of the existing situation, T1 and T3 believe that they planned the lesson without cooperation with the content subject teacher and T2 doubted the cooperation. T1 asserted that she invited the parents to come to class for career day, and taught the students about the jobs that they did. This program was scheduled once a semester. T2 did not have any experience in inviting the outside community to come but AIESEC proposed its voluntary activities to the school. Similar to T2, T3 did not have any experience inviting outside community to class either but some EYL experts proposed their community service to the schools. Table 7 below helps explain the cooperation as reflected by the teachers:

Table 7: The teachers’ reflections in relation to cooperation

Table 7 clarifies that the current situation had not permitted them to cooperate with the other content subject teachers but they believed that they had managed the learning process involving all students in the activities based on the level. As Anderson et al. (2018) also found, teachers generally agree to cooperate with the school, parents, and other related stakeholders to have a more fruitful CLIL lesson.

After observing the teaching and learning activities in the selected classroom, it was found that most of the CLIL core features have been implemented. Yet, it is still necessary to examine the EYL teachers’ understanding of the concept of CLIL Core Features reflected from their teaching since it is one of the influential factors in teachers’ decision making in the classroom. Further, the gap between their understanding and the real teaching activities can be identified from some possible improvements for more effective teaching activities.

Conclusion

There are two practical implications of the findings which are (1) the prevalence of six core features of CLIL and (2) the teachers’ reflections about their teaching linked to those features. In the YLs’ CLIL classrooms, the integration of content learning and language learning aims at equipping the learners with experience of using English for learning specific knowledge. It is urgent for teachers to design lessons which attract learners’ participations without any language anxiety, with the cooperation of other teachers and stakeholders. To manifest this, teachers should have an understanding of CLIL pedagogical knowledge to scaffold learners’ English language awareness for perceiving the subject and carrying out the tasks.

The most remarkable CLIL core features implemented in the class were multiple foci, active learning, and scaffolding. As it was remarked earlier, the students were found active in the learning process, such as in delivering the questions to confirm specific information, asking the meaning of specific words, and getting into a discussion for individual and pair-work tasks using three different languages (Bahasa Indonesia, Bahasa Jawa, and English). In terms of cooperation, teachers of various backgrounds should work together during preparation, so their lesson planning should be considered as a collaborative process, not an individual one. Based on the fact that lower graders in primary school have less vocabulary building and English inputs, implementing soft-CLIL as suggested by Bentley (2010) will be feasible to be practiced with the current setting. Furthermore, by exploring the six core features of CLIL practiced by the aforementioned teachers, there should be an acceptable form of CLIL approach administration in Indonesia, particularly at the primary school level. This current research supports the previous findings from Mahmud (2020), Rohmah (2019), and Setyaningrum & Purwati, 2020) regarding the feasibility of adapting the CLIL approach for Indonesian primary schools due to the availability of materials from the thematic integrated book. Hence, the teachers’ iterations on dual-focused concept for teaching English to young learners and their understanding about the core features that have been delineated by the questionnaire analysis should be sustained by pedagogical exposure.

For further research, identical studies might be conducted in other levels of education such as secondary and tertiary education since the exploration of the CLIL approach in Indonesian context remains limited. More particularly, to reach more reliable evidence, action research or experimental research can be conducted in primary school to prove the effectiveness of CLIL for students’ content knowledge and language skills since this aspect is considered as the limitation of this study. Finally, CLIL intensive workshops can also be proposed as one of the topics of Teacher Professional Development programs in Indonesia.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank to the Head of National Unity and Politics Agency (Kesbangpol) of the municipality in East Java, Indonesia for officially giving permission to conduct this research. Also, the participation of three selected primary teachers is highly appreciated.

References

Anderson, C. E., McDougald, J. S., & Medina, L. C. (2018). CLIL for young learners. In C. N. Giannikas, L. McLaughlin, G. Fanning, & N. D. Muller (Eds.), Children learning English: From research to practice (pp. 137–152). Garnet Education.

Andriani, P. F., Padmadewi, N. N., & Budasi, I. G. (2018). Promoting autonomous learning in English through the implementation of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in science and maths subjects. SHS Web of Conferences, 42. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184200074

Arham, M., & Akrab, A. H. (2018). Delving into content lecturers’ teaching capability in content language integrated learning (CLIL) at an Indonesian university. Asian ESP Journal, 14(7), 68–89.

Bautista, M. L. S., & Gonzales, A. B. (2006). Southeast Asian Englishes. In B. B. Kachru, Y. Kachru, & C. L. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of world Englishes (pp. 130-144). Blackwell.

Bentley, K. (2010). The TKT course: CLIL module. Cambridge University Press.

Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

Ching, F., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2019). Context of learning in TEYL. In S. Garton, & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of teaching English to young learners (pp. 95-109). Routledge.

Coelho, M. (2017). Scaffolding strategies in CLIL classes – Supporting learners towards autonomy. In M. C. Arau Ribeiro, A. Gonçalves, & M. Moreira da Silva (Eds.), Languages and the market: A ReCLes.pt selection of international perspectives and approaches (pp. 106–114). ReCLes.pt--Associação de centros de línguas do ensino superior em Portugal.

Copland, F., Garton, S., & Burns, A. (2014). Challenges in teaching English to young learners: Global perspectives and local realities.TESOL Quarterly, 48(4), 738-762. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.148

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Divljan, S. (2012). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in teaching English to young learners. The Ministry of Education and Science of Serbia.

Dobson, A. (2020). Context is everything: Reflections on CLIL in the UK. The Language Learning Journal, 48(5), 508-518.https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1804104

Gallardo-del-Puerto, F., Basterrechea, M., & Martinez-Adrian, M. (2020). Target language proficiency and reported use of compensatory strategies by young CLIL learners. International Journal Applied Linguistics, 30(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12252

García Esteban, S. (2015). Soft CLIL in infant education bilingual contexts in Spain. International Journal of Language and Applied Linguistics, 1, 30–36.

Ellison, M. (2019). CLIL in the primary school context. In S. Garton, & F. Copland (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of teaching English to young learners (pp. 247-268). Routledge.

Graham, K. M., Choi, Y., Davoodi, A., Razmeh, S., & Dixon, L. Q. (2018). Language and content outcomes of CLIL and EMI: A systematic review. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.2

Correa-Guzmán, J. M. C. (2017). Integration of CLIL fundamentals and principles in the initial cycle at San Bonifacio de las Lanzas School[Unpublished masters thesis]. Universidad Internacional de La Rioja. https://reunir.unir.net/handle/123456789/5112

Huang, Y.-C. (2020). The effects of elementary students’ science learning in CLIL. English Language Teaching, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n2p1

Huzairin, Sudirman, & Hasan, B. (2018). Developing English learning model project based content and language integrated learning (CLIL) for English at university level in Indonesia. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(11), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.511.5525

Inayati, N., Rachmadhani, R. A., & Utami, B. N. (2021). Student’s strategies in online autonomous English language learning. Journal of English Educators Society, 6(1), 59-67. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v6i1.1035

Izzah, I., Rafli, Z., & Ridwan, S. (2018). The model of Bahasa Indonesia teaching materials taken from stories in Quran taught with Content and Language Integrated Learning approach. Language Circle: Journal of Language and Literature, 12(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.15294/lc.v12i2.14172

Jayanti, D., & Sujarwo, A. (2019). Bilingual education in Indonesia: Between idealism and the reality. Script Journal: Journal of Linguistic and English Teaching, 4(1), 12-24. https://doi.org/10.24903/sj.v4i1.271

Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.). English in the World: Teaching and learning the language and literatures. Pergamon Press.

Khomsah, A. N., & Subjantoro, S. (2019). Developing evaluative descriptive text with Rebecca M. Valette’s taxonomy and CLIL approach. Seloka: Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa Dan Sastra Indonesia, 8(2), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.15294/seloka.v8i2.34401

Kirkpatrick, A. (2012). English as an international language in Asia: Implications for language education. In A. Kirkpatrick, & R. Sussex (Eds.), English as an international language in Asia: Implications for language education (pp. 29-44). Springer.

Kirkpatrick, A., & Liddicoat, A. J. (2020). English and language policies in East and Southeast Asia. In K. Bolton, W. Botha, & A. Kirkpatrick (Eds.), The handbook of Asian Englishes. (pp. 81-105). Wiley.

Lopriore, L. (2018). Reframing teaching knowledge in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): A European perspective. Language Teaching Research, 24(1), 94-104 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818777518

Mahmud, Y. S. (2020). Conceptualizing bilingual education programs through CLIL and genre-based approach: An Indonesian context. VELES Voices of English Language Education Society, 4(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.29408/veles.v4i1.2005

Manafe, N. R. (2018). Making progress in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) lessons: An Indonesian tertiary context. SHS Web of Conferences, 42. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184200111

Mariño, C. M. (2014). Towards implementing CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) at CBS (Tunja, Colombia). Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(2), 151-160. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.2.a02

McKay, S. L. (2018). English as an international language: What it is and what it means for pedagogy. RELC Journal, 49(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217738817

Mehisto, P. (2012). Criteria for producing CLIL learning material. Encuentro, 21, 15–33.

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, M. J. (2008). Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning in bilingual and multilingual education. Pearson.

Meyer, O. (2011). Introducing the CLIL-pyramid: Key strategies and principles for CLIL planning and teaching. In M. Einsenmann, & T. Summer, Basic Issue in EFL Teaching (pp. 295-313). Universitätsverlag.

Mukminatien, N., Yaniafari, R. P., Kurniawan, T., & Wiradimadja, A. (2020). CLIL audio materials: A speaking model for Library Science Department Students. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 15(7), 29-41. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i07.13223

Mukminin, A., Haryanto, E., Sutarno, S., Rahma Sari, S., Marzulina, L., Hadiyanto, & Habibi, A. (2018). Bilingual education policy and Indonesian students’ learning strategies. Elementary Education Online, 17(3), 1204–1223. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2018.466330

Nugroho, A. (2020). Content and language integrated learning practice in English for accounting course. Indonesian Journal of English Teaching, 9(2), 172–181. https://doi.org/10.15642/ijet2.2020.9.2.172-181

Nunan, D. (2018). Teaching speaking to young learners. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0715

Ouazizi, K. (2016). The effects of CLIL education on the subject matter (mathematics) and the target language (English). Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 9(1), 110–137. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2016.9.1.5

Pinner, R. (2013). Authenticity of purpose: CLIL as a way to bring meaning and motivation into EFL contexts. Asian EFL Journal Research Articles, 15 (4), 49-69. https://www.elejournals.com/963/2014/asian-efl-journal/the-asian-efl-journal-quarterly-volume-15-issue-4-december-2013

Puspitasari, E. (2016). Classroom activities in content and language integrated learning. Journal of Foreign Languange Teaching and Learning, 1(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18196/ftl.129

Rallis, S. F., & Rossman, G. B. (2009). Ethics and trustworthiness. In J. Heigham & R. A. Croker (Eds.), Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction (pp. 263–287). Palgrave Macmillan.

Rohmah, I. I. T. (2019). The feasibility and effectiveness of integrating content knowledge and English competences for assessing English proficiency in CLIL. ETERNAL (English Teaching Journal), 10(1). https://doi.org/10.26877/eternal.v10i1.3909

Sarip, M., Rafli, Z., & Rahmat, A. (2018). Arabic speaking material design using Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL).International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies, 5(1), 272–286.https://www.ijhcs.com/index.php/ijhcs/article/view/3253/3027

Setyaningrum, R. W., & Purwati, O. (2020). Projecting the implementation feasibility of CLIL approach for TEYL at primary schools in Indonesia. Journal of English Educators Society, 5(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v5i1.352

Setyomurdian, A. N., & Subyanto, S. (2018). The development of learning material of reading complex procedure text with CLIL approach for vocational high school students. Seloka: Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa Dan Sastra Indonesia, 7(2), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.15294/seloka.v7i2.25411

Shin, J. K., & Crandall, J. A. (2014). Teaching young learners English: From theory to practice. Heinle Cengage Learning.

Simbolon, N. E. (2020). CLIL practice in a maritime English course: EFL students’ perception. EduLite: Journal of English Education, Literature and Culture, 5(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.30659/e.5.2.263-276

Suhandoko, S. (2019). CLIL-oriented and task-based EFL materials development. ELT Worldwide, 6(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.26858/eltww.v6i2.10662

Sulistiyo, U., Haryanto, E., Widodo, H. P., & Elyas, T. (2020). The portrait of primary school English in Indonesia: Policy recommendations. Education 3-13, 48(8), 945–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1680721

Suwannoppharat, K., & Chinokul, S. (2015). Applying CLIL to English language teaching in Thailand: Issues and challenges. Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 8(2), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.5294/3163

Uztosun, M. S. (2018). Professional competences to teach English at primary schools in Turkey: A Delphi study. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(4), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1472569

van Kampen, E., Admiraal, W., & Berry, A. (2018). Content and language integrated learning in the Netherlands: Teachers’ self-reported pedagogical practices. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(2), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1154004

Wahyuni, S. (2016). Curriculum development in Indonesian context the historical perspectives and the implementation. Universum, 10(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.30762/universum.v10i1.225

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.

Yulianti, K. (2015). The new curriculum implementation in Indonesia: A study in two primary schools. International Journal about Parents in Education, 9(1), 157–168. http://web.archive.org/web/20200714235220/http://www.ernape.net/ejournal/index.php/IJPE/article/view/317/255

Zein, M. S. (2017). Elementary English education in Indonesia: Policy developments, current practices, and future prospects. English Today, 33(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078416000407

[1] AIESEC (Association Internationale des Étudiants en Sciences Économiques et Commerciales) is a global platform for youth worldwide run by students and recent graduates of institutions of higher education. Most of the non-profit activities cover global issues, leadership, education and management. In education, some of members are travelling around the world to teach in several regions in developing countries like Indonesia.