Introduction

What teachers believe in seems to influence their teaching practices. In lesson planning and teaching, they make constant decisions that are shaped by their beliefs, such as how to pace the lesson, set up different activities, ask questions, explain a certain language point, etc. Different studies have thus shown the impact of their different beliefs in the classroom. For example, Thu (2009) argued that EFL teachers considered grammar a crucial element in mastering the English language and that it should be taught explicitly through a deductive or inductive approach. The author also claimed that teachers believed errors should be corrected even if the message is comprehensible. On the other hand, Azar’s (2013) findings indicated that teachers believed grammar is an essential component of language lessons. They used an explicit approach and a contextualized use of grammar targeting the four skills.

In the same vein, Toro et al. (2019) examined the Communicative Approach (CA) in Ecuador and found that half of the teachers stated they would use metalinguistic terms when giving feedback. They stated that teachers used both pair and group work in different activities, and most of these teachers expressed that they did not always use the target language in the classroom. Moreover, grammar teaching in EFL classrooms has always held and still holds a central position as researchers and methodologists have claimed that it is both necessary and essential to reaching foreign language competence in terms of accuracy and fluency (Hinkel & Fotos, 2002). Recent suggestions strongly advocate the use of grammar while using CA.

In Peru, regarding the approach teachers use in their classrooms, since 2016 the Ministry of Education has established CA as the main approach for teachers to use in their lessons. This approach is based on the principle that the main function of a language is to convey meaning, and its objective is the development of communicative competence (Richards, 2006). To date, this approach has been one of the most widely used in English as Foreign Language (EFL) contexts, such as schools and institutions, and the different aspects of this approach are often misunderstood or taken for granted. Research on the effectiveness of such an approach suggests that it enhances learners’ communicative ability and motivation for learning. For example, Ahmad and Rao (2013) reported that implementing CA boosted students’ communicative ability at secondary schools and increased their motivation for learning as long as suitable conditions were provided. Mehta (2015) also asserted that students enhanced their four skills after implementing CA at a school and improved their grammatical competence. In addition, students felt more conformable from the beginning and enjoyed the different classroom activities such as games and speaking tasks. Similarly, Ibrahim (2018) indicated that communicative language teaching (CLT) is far more effective than other traditional methods to attain language proficiency in the classroom and that the incorporation of the different CLT’s procedures and principles is effective in the language classroom. Chen (2015) investigated the effects of practicing CA in a mixed English conversation class revealed and found that learners felt more comfortable with the incorporation of CA in the classroom and that using their first language (L1) was beneficial in reducing their anxiety.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that different studies concerning the teachers’ use of CA have shown that teachers have misunderstood many of their aspects, such as the inclusion of grammar in the lessons, the use of mother language, metalanguage, and error correction (Alghanmi & Shukri, 2016; Hos & Kekec, 2014; Thu, 2009). Therefore, the different aspects of grammar teaching should be clarified within the EFL context, considering the educational context of teachers. Furthermore, research on teachers’ beliefs will give insight into the cognitive motives behind their pedagogical decisions.

Purpose of the study

Since studying teachers’ beliefs about grammar teaching is essential for improving teaching practices and implementing the CA successfully, this study aimed to identify the beliefs of teachers from Piura about grammar teaching within the CA. Although teachers’ beliefs have been examined in numerous previous studies (Alghanmi & Shukri, 2016; Azad; 2013; Borg, 2003; Ezzi, 2012; Onalan, 2018; Thu, 2009), to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, there have been no studies on this topic conducted in the Peruvian context.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of grammar teaching within CA in this paper is divided into six different categories: the definition of grammar, the Communicative Approach, the approach to present grammar, the use of the mother tongue, the use of grammar terminology and error correction. All these aspects are dealt with in the context of teaching EFL.

Definition and the importance of grammar

Despite the fact that there have been different definitions of grammar, most focus on its structural aspect without considering its context or use (Brown, 2007; Harmer, 1987, Ur, 1999). On the other hand, Larsen-Freeman (2014) defines it within three elements: form, meaning, and use. As a result, grammar not only focuses on the morphological or syntactical aspects, but also on what a grammatical structure means and its use in different contexts. Thus, a more holistic view of grammar is needed to have a positive teaching experience.

When it comes to the importance of grammar teaching, Ellis (2006), Hinkel and Fotos (2002), and Ur (1999) state that it is important to teach grammar in EFL contexts as it helps students to reach an appropriate level of accuracy in the language. Additionally, Long and Richards (1987) also emphasize that grammar helps students improve their language skills, such as reading, listening, speaking, and writing as well as their vocabulary. Therefore, grammar teaching seems to be essential in EFL classrooms as it gives students the tools to communicate effectively and reach a level of competence in English.

Grammar should also be taught in context; that is, through the simulation of different situations (Harmer, 2001; Mart, 2013; Nunan, 1998), as this allows students to understand the use of grammar and the function of the different grammatical structures in different situations (Spratt et al., 2011).

The Communicative Approach

According to Larsen-Freeman and Anderson (2013), CA is based on the premise that language is used for communication and aims to make communicative competence the main goal of language teaching. In other words, language teaching should emphasize the use of language in context. According to Canale & Swain (1980), communicative competence is the ultimate goal of CA and is divided into four areas. The first is grammatical competence which deals with the knowledge of language structures. The second is sociolinguistic competence which refers to the ability to appropriately express and understand messages in different contexts. The third is discourse competence which has to do with the ability to combine grammar and meaning to produce both spoken and written coherent texts. The last is strategic competence which involves using strategies, such as clarification requests and self-correction, to convey meaning and address difficulties between the different speakers.

This approach works in the classroom by applying principles rather than following a particular method. Therefore, in a communicative classroom, for example, learners learn language by using it to communicate through authentic and meaningful interaction with a focus on meaning and form. Furthermore, it also involves the integration of the four language skills and the process of discovering language.

Approaches for grammar teaching

Concerning the methodology of grammar teaching, there are four main approaches, deductive, inductive, explicit, and implicit. In the deductive approach, according to Thornbury (1999), grammar teaching starts by presenting rules and structures along with a practice stage. Conversely, in the inductive approach, examples of the language are presented, and students work out the rules and uses of the language. A stage of further practice also follows this. As defined by Scott (1990), the explicit approach to grammar teaching involves deliberately studying grammar rules to recognize the linguistic elements accurately. The implicit approach, by contrast, states that students should be exposed to language structures in context to acquire them naturally without being conscious of the rules. The deductive approach is related to a conscious process of learning in which explicit rules are presented and practised. For this reason, it is an efficient way to organise and present grammar rules which can enhance students’ confidence when doing certain activities. On the other hand, the inductive approach is related to a subconscious process of learning in which the teacher presents grammar with examples of sentences so that students can understand grammatical rules from the examples; in so doing, this approach tries to highlight grammatical rules implicitly (Ellis, 2006).

Thornbury (1999) considers that the choice of using a deductive or inductive approach depends on various factors such as students’ age, cognitive style, and language level. For example, with some young adult students, a deductive approach might be more suitable than with young learners; in other words, both approaches can be successfully applied in the classroom depending on the type of students. This requires that both approaches are important when teaching grammar and that neither is better than the other. Nevertheless, according to DeKeyser (2017), in EFL contexts, some language explicitness is essential to automatize grammar structures through systematic practice. In such a context, language learning is largely a conscious process that entails using grammar rules that must be explicitly stated followed by corrective feedback while encouraging correct usage.

The use of first language

In EFL lessons, students are not in constant contact with the language and bring their L1 into the classroom. In this context, teachers can use the students’ L1 to their advantage in order to facilitate the process of learning (Demir, 2012), and avoiding it can imply that learners’ previous experiences are not important in the classroom. However, teachers should consider different aspects when using it, such as the object of lesson, students’ ages, prior learning experience, and language level. In this regard, Cook (2001) proposes four guidelines to be considered for judging when to use L1. The first factor is efficiency. For example, L1 can be effective when checking comprehension or giving instructions. The second factor is learning. This means that L1 should facilitate the learning process. The third factor is naturalness. L1 can be used when possible, and its use meets students’ needs and thus creates an environment of rapport. The fourth factor refers to external relevance, which means knowing how L1 might help students succeed in their real-life needs, such as when presenting a product in L1 and English in their jobs. As for grammar explanations, Cook (2001) also asserts that L1 can be a shortcut to lessen the cognitive burden of dealing with complex grammatical structures.

Additionally, L1 can help students be aware of the differences between L1 and English grammar, and it can eliminate adverse inferences from L1. However, its use also could have a negative effect. For example, Atkinson (1987) identifies that when L1 is overused, students start to feel that they have not understood a language point until a translation is provided. They also might tend to use L1 when they can use English. Furthermore, they might fail to realize the importance of using English in the classroom.

The use of L1 in EFL classrooms is therefore justified. As Pan and Pan (2010) said, it should not have the same status as English, but research shows that it is an effective tool for foreign language learning and a useful resource in the classroom. It should also be kept in mind that the amount of L1 depends on the student’s language level and teaching purposes.

The use of metalanguage

The next aspect of grammar teaching is the use of grammar terminology or metalanguage which is defined as the use of grammar expressions such as subject, predicate, noun, verb, present simple, past simple, etc. in the communicative language classroom (Ellis, 2016). He asserts that, as in CA, the medium and object of instruction, the English language, overlaps. The use of metalanguage can be a tool to support language learning when students seek and receive explanations of language points. Therefore, there is a place for metalanguage in communicative language teaching.

Although authors often disagree on whether it should be used in grammar teaching, it is an important tool with different advantages for EFL students. For instance, according to Ellis (2016), it can facilitate the development of metalinguistic consciousness to develop accuracy and precision in English. In EFL classrooms, there should be a level of explicitness of language; students need to know some grammar terminology such as tense, transitive verb, past tense, etc. The use of metalanguage can assist students link new grammatical structures with knowledge of grammar that has already been acquired and, in that way, serve as a point of reference for integrating new knowledge.

Ellis (2016) suggests the following. Teachers need to adapt metalanguage when working with low-level learners more than with students with higher language competence. The type of activity is also important. For example, some classroom activities require using metalanguage, such as the Communicative Dictogloss. The next factor is students’ prior experience which refers to whether students are familiarized with some language terms in advance. Finally, students’ age should also be considered since metalanguage can be used with students who are cognitively ready to deal with different grammatical terms, as is the case of secondary students. Recently, Hu (2010) has shown a somewhat positive correlation between students’ use of metalanguage and their language competence, although more research is needed to confirm this premise.

Error correction

As regards error correction, teachers should be aware that it is important to promote the development of language competence (Amara, 2015). Nonetheless, this should not be overestimated (Ur, 1999) as it can negatively affect students’ confidence and language performance. As for the types of errors to be corrected, different authors (Burt, 1995; Ellis, 2009: Pawlak, 2013) suggest that not all errors should be corrected, only those which are the focus of the lesson and which teachers consider essential to foster language accuracy. In terms of the moment in which errors should be corrected in the classroom, Amara (2015), Harmer (2001), and Hughes (2002) consider that in speaking activities, teachers should delay the correction if the focus of the activity is on fluency. On the other hand, immediate correction is effective if the activity focuses on accuracy. As for who should correct the errors in speaking activities, there are three options, teacher correction, self-correction, and peer correction, each of which can be used in different moments of the classroom considering different aspects such as the target language and students’ level (Pawlak, 2013). Furthermore, multiple sources of feedback contribute to students’ learning and reflection (Carroll, 2006).

To conclude, this brief literature review reveals that grammar teaching in EFL contexts has certain particularities about different aspects, which can be effective for learning and teaching English. Therefore, it is important to investigate teachers’ beliefs regarding the aspects of grammar teaching and determine whether those beliefs correspond with what is stated in the literature.

Accordingly, this study seeks to identify teachers’ beliefs regarding the aspects of grammar teaching within the Communicative Approach through a questionnaire. Therefore, the design was guided by the question: What are the teachers’ beliefs regarding grammar teaching within CA?

Methodology

This study is a non-experimental quantitative one whose objective is to identify teachers’ beliefs about grammar through a quantitative analysis of frequencies and percentages.

Context and participants

The context of this study was English language teachers in Piura, Peru. In this country, the National Curriculum includes EFL classes from the third year of primary education to the fifth grade of secondary school. Students from 7-10 years old belong to the primary level education, and students from 12-16 years old belong to the secondary level. Students are expected to reach a B2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) at the end of their secondary level. CA is explicitly prescribed to be used in English language lessons to promote students’ language competence (Ministerio de Educación, 2016). Furthermore, secondary public schools in Piura are required to have two to four hours of English instruction per week.

All public secondary schools in Piura were invited to participate in the study. However, only fifteen schools agreed to be part of the research. From those schools, all teachers of English at the secondary level, thirty-five in total, completed a questionnaire. The researcher visited the schools twice; the first was to inform coordinators, directors, and teachers about the purpose of the study and to sign in a letter of consent, and the second was to have teachers complete the questionnaire. Teachers were not asked to give their names or any identifying information to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

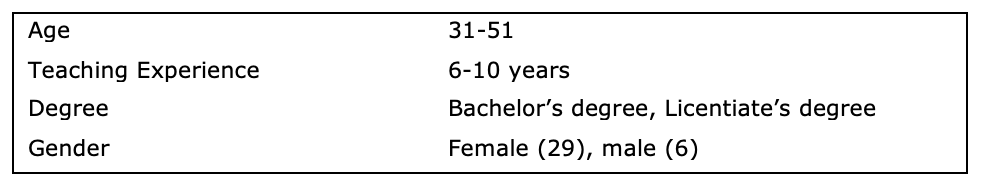

It is essential to mention that only secondary teachers were invited to participate in the study as the different aspects of grammar teaching are directed at students at a secondary level. Table 1 indicates the sociodemographic profile of the teachers.

Table 1: Sociodemographic profile of the participants

Instruments

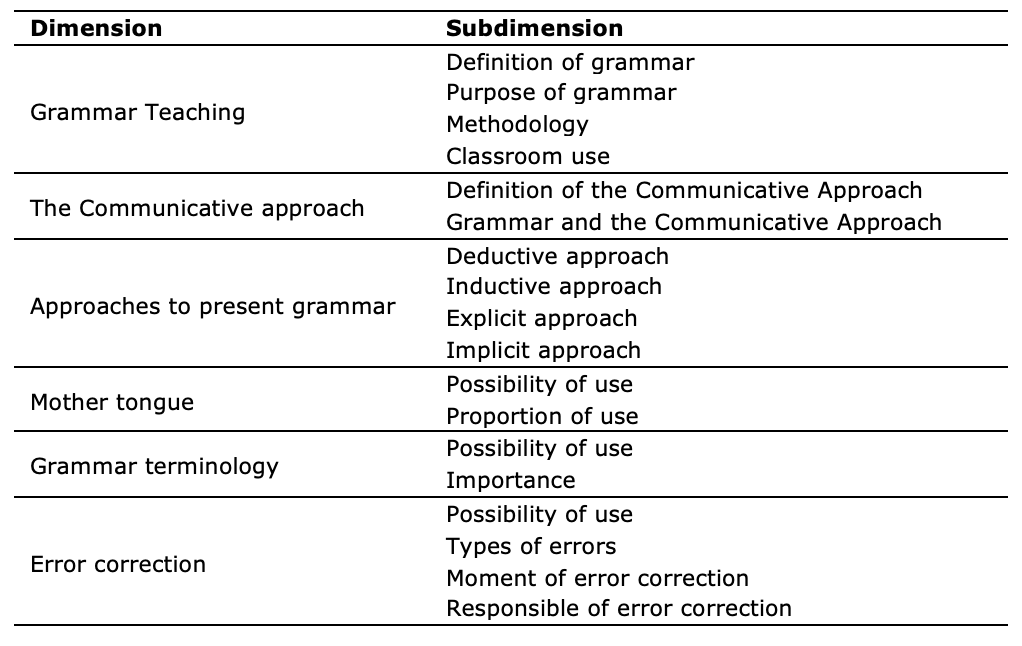

A self-made survey was created to fulfil the purpose of the study. The questionnaire consisted of twenty-seven close-ended questions, and used a four-point Likert scale to measure the frequency of reported beliefs. Three professors validated the survey at Universidad de Piura and they suggested different changes to adjust the instrument and evaluated its effectiveness. As for reliability, a pilot test was used. Thus, seven teachers from different schools from another district completed the questionnaire. Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated, resulting in 0.809 from the responses, demonstrating that the questionnaire had enough internal consistency. Data were analysed with IBM SPSS 23 Software, and basic descriptive statistics was used to calculate the frequency of the items. The questionnaire comprised six aspects and twenty-seven questions. Table 2 shows the different dimensions and subdimensions.

Table 2: Dimensions of the instrument

Results and discussion

The questionnaire data was organized into tables showing the descriptive statistics for each statement. In this study, the participants’ responses have been shown in percentages and frequencies.

About grammar teaching

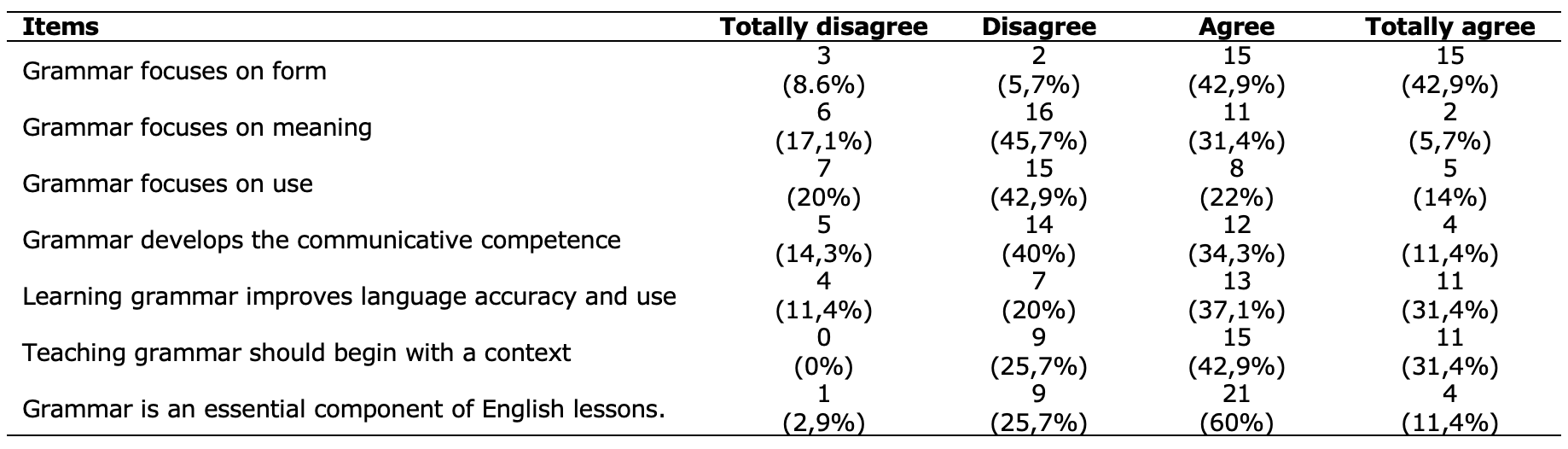

The results in Table 3 show that most teachers believed that grammar focuses on form and disagreed with the idea that grammar focuses on meaning and use. This shows a common misconception that grammar only focuses on the form of a structure and not on how it is used (Spada, 2007). These results coincide with those in the study of Alghanmi & Shukri (2016), in which it was revealed that most teachers also believe that grammar focuses on form.

Concerning the purpose of grammar, almost half of the teachers had dissenting views. This contrasts with Alghanmi & Shukri (2016), who found that 67% of teachers believed that grammar develops communicative competence. Moreover, in this study, teachers mostly believed that grammar improves language accuracy and use, that it should be taught within a context and that it is an essential aspect of their lessons. Similarly, Onalan (2018) revealed that more than half of the teachers reported believed that grammar improves accuracy and use. Regarding whether grammar is essential for the lessons, the results of the present study indicated that grammar was considered an important element in the lessons. This contrasts with Hoc & Kekec’s (2015) findings, in which half of the teachers disagreed with a similar statement.

Table 3: Results about grammar teaching

About the Communicative Approach

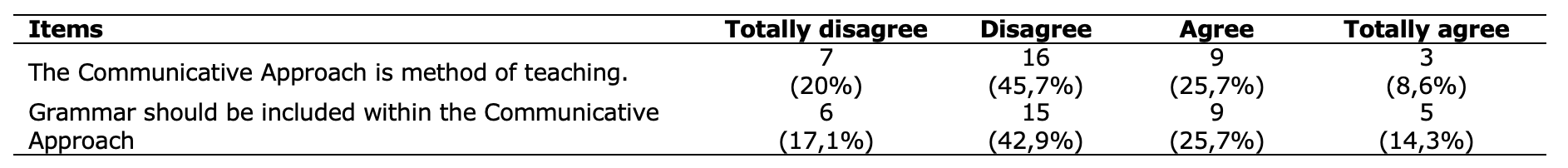

The results in Table 4 show that teachers generally believed that CA is not a teaching method and that the actual concept of CA is a set of principles underpinning teaching. As for the inclusion of grammar within CA, teachers had a misconception since they pointed out that it should not be included in such an approach. This result coincides with Onalan’s (2018) findings, which revealed that 73% of teachers disagreed with including grammar in CA. Teachers’ belief about the inclusion of grammar in CA might be explained by the fact that at a theoretical level, teachers believe that grammar is incompatible with CA.

Table 4: Results about the Communicative Approach

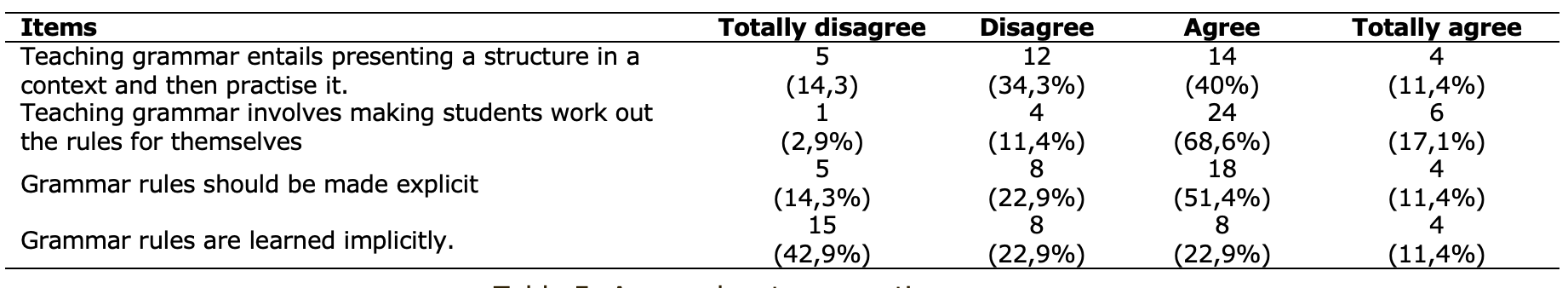

Approaches for grammar teaching

Regarding the approaches used to present grammar, Table 5 shows that most teachers preferred using the inductive approach when presenting grammar. Contrarily, the results of the study by Jusmaya & Afriana (2017) showed that teachers had a preference for a deductive approach. Teachers from this study might have opted for an inductive approach because it is in line with the guided-discovery way of learning, a concept teachers are familiar with because of the National Curriculum. Additionally, the teachers in this study also held the view that there should be an element of explicitness in grammar teaching, which is in line with the results found in Ezzi (2012), in which most teachers disagreed with the idea of learning grammar implicitly.

Table 5: Approaches to presenting grammar

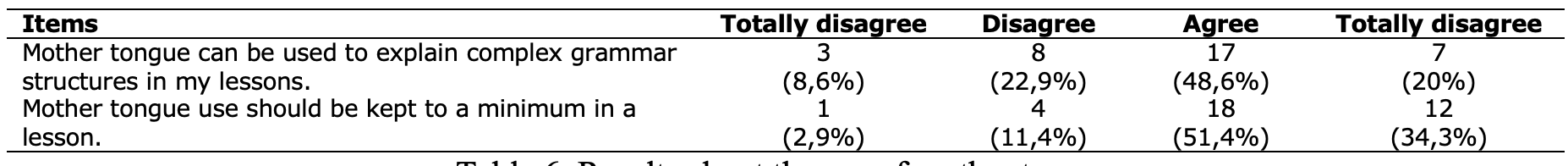

About the mother tongue

Table 6 shows that most teachers believed that the mother tongue is a tool to explain specific complex grammatical structures. However, it is difficult to determine which structures are more complex than others, which is something beyond the scope of the present study. This result coincides with Zacharias (2004) who found that most of the teachers reported using L1 to explain grammatical concepts. The teachers in this study also considered that mother tongue use should be kept to a minimum. This is also in line with Zacharias (2014), who stated that teachers expressed that L1 should not be used at all times. Due to the nature of the instrument, it was challenging to determine how teachers decide when to use their mother tongue.

Table 6: Results about the use of mother tongue

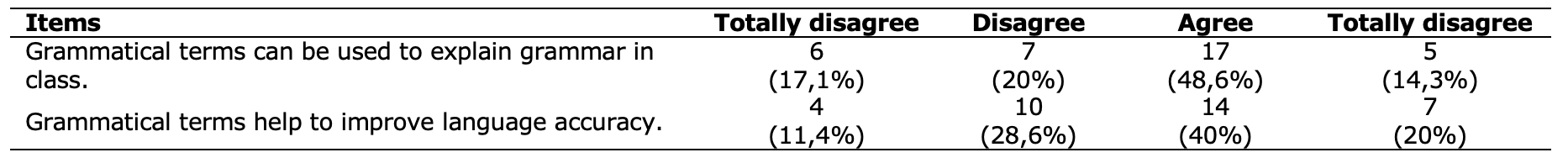

About grammar terminology

Concerning grammar terminology, Table 7 shows that teachers mostly believed that metalanguage is an element that can be used to explain grammar in class. Including this tool in CA is effective because it assists students in internalizing and better understanding of the structures (Hu, 2010). Furthermore, teachers also believed that such terms improve language accuracy. Contrarily, Shatat (2011) reported that almost 54% of teachers believed grammatical terms are unnecessary for language learning.

Table 7: Results about grammar terminology

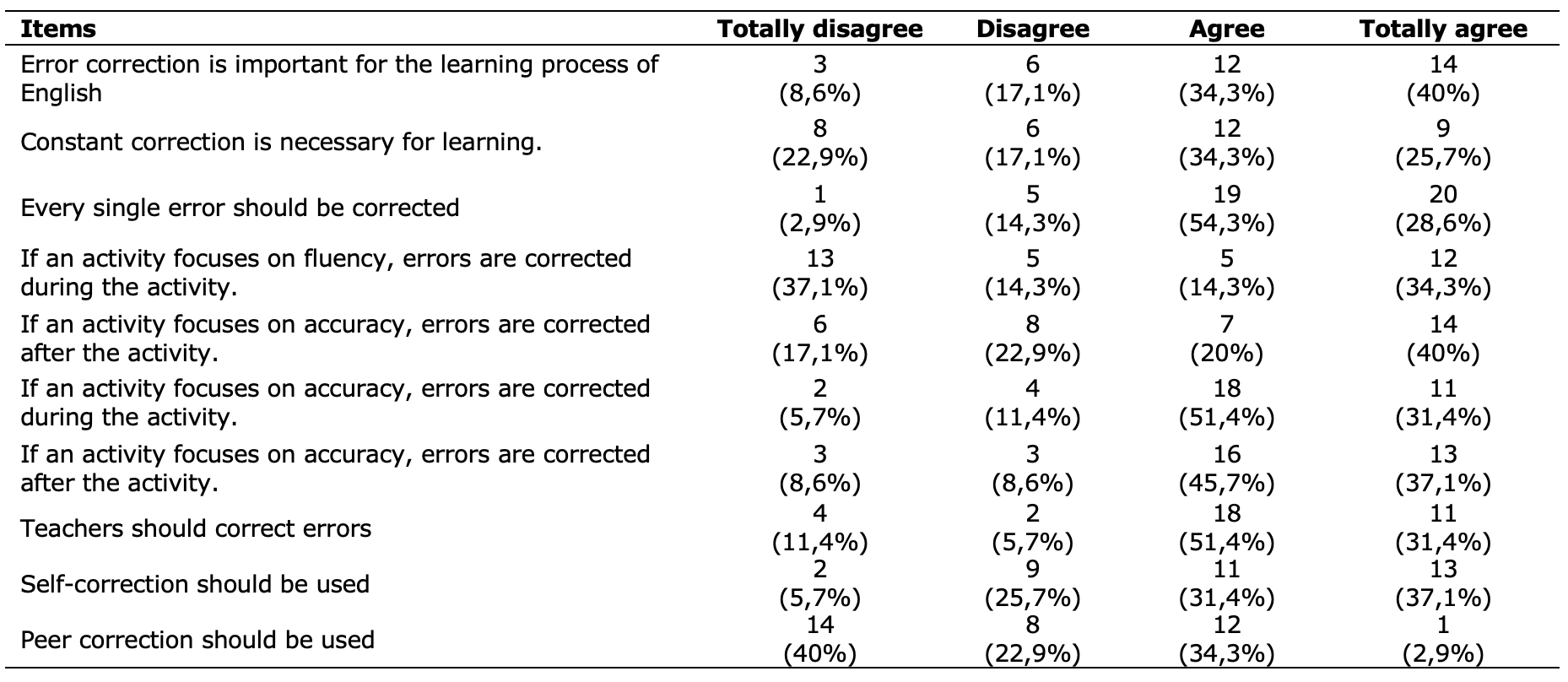

About error correction

In the present study, most teachers believed that error correction is an important aspect of the learning process, as shown in table 6. Similarly, Shatat (2011) also found that teachers agreed with a similar statement. Contrary to Baleghizadeh & Farshchi (2009), who reported that about 53% of teachers agreed with correcting only some errors, most of the teachers in this study agreed that constant correction is necessary. This means that teachers constantly correct errors in the classroom.

Regarding the types of errors, teachers mainly considered that every single error should be corrected. This is opposed to what Ellis (2009) and Burt (1975) state about the types of errors to be corrected; only a few focused errors should be corrected. Concerning error correction, it is noticeable that teachers did not distinguish between the activities and believed that error correction should be done at any moment in the lesson. This contradicts the study of Shatat (2011), in which teachers preferred immediate error correction.

Finally, regarding the person in charge of making corrections, teachers in the present study generally considered that they should oversee the error correction as well as the students themselves and tended to neglect the use of peer correction in the lessons. It should be noted that Amara (2015) points out that different agents should do error corrections to promote collaboration in the classroom. The results of this aspect contrast with those in Wang et al. (2018), in which teachers expressed their preference for self-generated and peer feedback.

It is necessary to mention that the exclusive use of one agent to correct errors, be it the teacher, peers, or the students themselves, can harm language learning; thus, there should be variety when it comes to who corrects learners’ errors.

Table 8: Results about error correction

Limitations

The present results can only be generalized to the context of teachers working in secondary public schools in Piura, Peru. It is important to mention that the results represented an attempt to explore the teachers’ beliefs. More instruments are needed to reach a wider range of conclusions, such as interviews or an open-ended questionnaire in which teachers can express their beliefs in a less controlled way. Such beliefs can be compared with their teaching practices in classroom observations to determine the correspondence between beliefs and practices. Additionally, some aspects of this study focused on speaking activities such as error correction. Research is needed to explore teachers’ beliefs on error correction in speaking activities. The present study can also be extended by comparing the beliefs of private and public school teachers.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicated that many teachers from Piura had a limited perspective of grammar, as they only focused on form. Nonetheless, they considered it essential to their lessons and believed it helps improve language accuracy and use. They also believed that it should be taught in context. Regarding grammar teaching and CA, teachers held a common misconception as they assumed that grammar should not be included within CA. Although this might seem contradictory, it can be inferred that teachers may consider CA and grammar as two different aspects of their praxis. Such a view could have a negative impact on learning and teaching because grammar lessons might merely focus on mechanical exercises or drills.

Regarding the approach which they used to present grammar, teachers preferred for the inductive approach in which students worked out the rules for themselves and believed that a level of explicitness is necessary when teaching grammar. As for the use of L1, teachers generally believe that it is an important element in the classroom but should not be overused. This view is in line with what is stated in the literature about L1 use. However, the amount of L1 teachers use in the classroom and how they use it are aspects beyond the scope of this study that can be explored in another study considering these results.

Interestingly, many teachers considered the use of metalanguage effective in teaching grammar. Such a view can have a positive effect on students’ learning as the use of metalanguage is recommended in EFL lessons. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to explore the number of grammatical concepts teachers use in their lessons and at what moment they use them.

Regarding error correction, this is an aspect to which teachers paid close attention as they considered constant correction necessary. This can harm students as constant correction can refrain students from using English in the classroom for fear of being corrected. However, teachers still held common misconceptions about the types of errors to be corrected and the moment in which an error should be corrected; that is, they indicated not to consider the type of activity when correcting errors. Moreover, they emphasized the role of the teacher when carrying out error correction. They tended to neglect the role of peer- and self-correction, which might result in the teacher overcontrolling error correction in the classroom.

The teachers’ different beliefs can give an insight into their teaching practices and the possible implications of implementing CA in Peru. Furthermore, the results of this study can also offer some guidelines for teacher trainers to address the common misconceptions teachers have, thereby debunking some misguided beliefs about grammar teaching and thus improving their teaching practices.

References

Ahmad, S., & Rao, C. (2013). Applying communicative approach in teaching English as a foreign language: a case study of Pakistan. Porta Linguarum, 20, 187-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.24882

Alghanmi, B., & Shukri, N. (2016). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs of grammar instruction and classroom practices in the Saudi context. English Language Teaching, 9(7),70-86. https:/doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n7p70

Amara, N. (2015). Errors correction in foreign language teaching. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 5(3), 58-68. https://www.tojned.net/journals/tojned/articles/v05i03/v05i03-07.pdf

Atkinson, D. (1987) ‘The mother tongue in the classroom: a neglected resource?’. ELT Journal 41(4), 241-247. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/41.4.241

Azad, M. A. K. (2013). Grammar teaching in EFL classrooms: Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. ASA University Review, 7(2). 111-126. http://www.asaub.edu.bd/data/asaubreview/v7n2sl10.pdf

Baleghizadeh, S., & Farshchi, S. (2009). An exploration of teachers' beliefs about the role of grammar in Iranian high schools and private language institutes. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 1(212), 17-38. https://elt.tabrizu.ac.ir/article_639_4fa2bee657d7c98935a1528e8d53f48a.pdf

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language teaching, 36(2), 81-109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444803001903

Brown, H. D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Pearson Education.

Burt, M. K. (1995). Error analysis in the adult EFL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 9(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586012

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/I.1.1

Carroll, C. (2006). Enhancing reflective learning through role-plays: The use of an effective sales presentation evaluation form in student role-plays. Marketing Education Review, 16(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2006.11488931

Chen, W.-W. (2015). A case study of action research on communicative language teaching. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics,18(6), 705-717. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720502.2015.1108075

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57 (3),402-423. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.3.402

DeKeyser, R. (2017). Knowledge and skill in ISLA. In S. Loewen & M. Sato (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 19-21). Routledge

Demir, H. (2012). The role of native language in the teaching of the FL grammar. Journal of Education, 1(2), pp. 21-28.https://jebs.ibsu.edu.ge/jms/index.php/je/article/view/59/67

Ellis, M. J. (2016). Metalanguage as a component of the communicative classroom. Accents Asia, 8(2), 143-153. http://www.issues.accentsasia.org/issues/8-2/wadden.pdf

Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 83-107. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264512

Ellis, R. (2009). Corrective feedback and teacher development. L2 Journal, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/L2.V1I1.9054

Ezzi, N. A. A. (2012). Yemeni teachers' beliefs of grammar teaching and classroom practices. English language teaching, 5(8), 170-184. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n8p170

Harmer, J. (1987). Teaching and learning grammar. Longman.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching. Longman.

Hinkel, E., & Fotos, S. (2002). From theory to practice: A teacher’s view. In E. Hinkel & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on grammar teaching in second language classrooms, (pp.1-12). Erlbaum

Hos, R., & Kekec, M. (2014). The mismatch between non-native English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers' grammar beliefs and classroom practices. Journal of Language Teaching & Research, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.1.80-87

Hu, G. (2010). A place for metalanguage in the L2 classroom. ELT journal, 65(2), 180-182. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq037

Hughes, R. (2002). Teaching and researching speaking. Longman.

Ibrahim, N. A. (2018). Investigating the significance of the communicative approach in teaching grammar and language learning activities—A case study of general English students at Red Sea University. Communication and Linguistics Studies, 4(3), 72-79.

Jusmaya, A., & Afriana. (2017). Teachers’ belief and classroom practices toward grammar instruction in the communicative language teaching. Applied Science and Technology, 1(1), 184-192. https://www.estech.org/index.php/IJSAT/article/view/33/pdf_1

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2014). Teaching grammar. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th ed.) (pp. 256-270). Heinle & Heinle.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Anderson, M. (2013). Techniques and principles in language teaching (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Long, M. H., & Richards, J. C. (Eds.). (1987). Methodology in TESOL: A book of readings. Newbury House.

Mehta, N. K. (2015). Communicative approach in learning English language: Effectiveness at middle school level (with special reference to government middle school of Ujjain city in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India). Limbaj şi context, 2, 113-118. https://doi.org/10.5281/zonodo.495104

Mart, Ç. T. (2013). Teaching grammar in context: why and how?. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(1), 124-129.https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.1.124-129

Ministerio de Educación Perú. (2016). Diseño curricular nacional [National Curriculum Design] Ministerio de Educación del Perú. http://www.minedu.gob.pe/curriculo/pdf/curriculo-nacional-de-la-educacion-basica.pdf

Nunan, D. (1998). Teaching grammar in context. ELT Journal 52(2), April 199. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/52.2.101

Onalan, O. (2018). Non-native English teachers’ beliefs on grammar instruction. English Language Teaching, 11(5), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n5p1

Pan, Y.-C, & Pan, Y-C. (2010). The use of L1 in the foreign language classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics, 12(2), 87-96. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.85

Pawlak, M. (2013). Error correction in the foreign language classroom: Reconsidering the issues. Springer.

Richards, J. C. (2006). Communicative language teaching today. Cambridge University Press.

Scott, V. M. (1990). Explicit and implicit grammar teaching strategies: New empirical data. The French Review, 63(5), 779-789. https://www.jstor.org/stable/395525

Shatat, Z. Y. M. (2011). Grammar teaching in Sharjah Preparatory (Cycle 2) Schools Teachers' beliefs and classroom practices [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] The British University in Dubai. https://bspace.buid.ac.ae/handle/1234/171

Spada, N. (2007). Communicative language teaching. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching, (pp. 271-288). Springer.

Spratt, M., Pulverness, A., & Williams, M. (2011). The TKT Course Modules 1, 2 and 3. Cambridge University Press.

Thornbury, S. (1999). How to teach grammar. Longman.

Thu, T. H. (2009). Teachers' perceptions about grammar teaching [ED507399]. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507399.pdf

Toro, V., Camacho-Minuche, G., Pinza-Tapia, E., & Paredes, F. (2019). The use of the Communicative Language Teaching Approach to improve students' oral skills. English Language Teaching, 12(1),110-118. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n1p110

Ur, P. (1999). A course in language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge University Press

Wang, B., Yu, S., & Teo, T. (2018). Experienced EFL teachers’ beliefs about feedback on student oral presentations. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0053-3

Zacharias, N. T. (2004). Teachers' beliefs about the use of the students' mother tongue: A survey of tertiary English teachers in Indonesia. English Australia Journal, 22(1), 44-52.