Introduction

People are different from each other due to their various perspectives of the world. In fact, how learners interact with the world and how they make decisions can not only affect their learning process (Marefat, 2006), but also justify their different learning styles (Ehrman & Oxford, 1995, Wilz, 2000). These differences are related to their non-identical personality types (Boroujeni et al., 2015) which can be defined as “an individual’s characteristic patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior, together with the psychological mechanisms, hidden or not, behind those patterns” (Funder, 2007, p. 5). Also, Mayer (2007) explained this term as “the organized, developing system within the individual that represents the collective action of that individual’s major psychological subsystems” (p.14). It can be stated that people’s personality types are consistent even over a specific time and they have the ability to affect all aspects of their lives on the one hand, and learning process on the other.

Writing can be considered to be one of the most difficult skills in language learning (Richards & Renandya, 2002), because it contains all the grammar and vocabulary points students have learned. In other words, “a learning experience is a highly individualized experience” (Bloom, 1976, as cited in Dwi Wulandri, 2010, p.273) in general, and writing is a type of individual expression in particular. More specifically, when learners try to develop writing competency, they tend to carry this out in individualized ways to achieve their purpose (Chastain, 1988) because each person has specific personality types which are different from others. Using productive skills, learners may experience a specific amount of anxiety (Zhang, 2001) which can be defined as “the worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (p. 27). Lowering their level of anxiety is considered to be a responsibility of the teacher because high anxiety can cause stress and inhibit learning (Sadeghi, 2014). This duty becomes even more necessary when students with advanced writing competence reach this level of anxiety when they engage in writing (Cheng, 2002).

As a result, learning is directly connected to affective states (Mansouri Nejad et al., 2012) which demonstrates that this emotional side of human behavior should not be eliminated from language learning. As Chastain (1988) stated, affection can play a key role in students’ interest or lack of interest in learning. Since the whole learning experiences depends on emotional reactions and personality types (Stern, 2010), investigating the relationship between different personality types and writing anxiety is worthy of more consideration.

Literature Review

Personality Types

Although different categorizations of personality types have been proposed, the Jungian personality traits by Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) has been preferred by many researchers (Matthews et al., 2009). MBTI, which measures personality along four dichotomies, namely, extroversion versus introversion, sensing versus intuition, thinking versus feeling, and judging versus perceiving. Extroversion vs. introversion differentiates people who either get their energy from the outer world of people or an inner world of ideas and experiences (Dörnyei, 2005), while sensing versus intuition refers to the way people perceive the world and gather information. More specifically, sensing concerns what is real as experienced through one or more of the five senses. Therefore, a sensing person tends to be interested in the observable physical world with its rich sensory details. In contrast, a person on the intuitive end of the continuum prefers to focus on the patterns and meanings in the data (Dörnyei, 2005). Based on Jensen & DiTiberio’s (1984) study, when it comes to writing, it has been said that sensing group can do their best if they are given explicit and specific instructions because general guidance blocks their comprehension. “Conversely, intuitives pay more careful attention to regulations if they know their original ideas do have an outlet for expression” (Jensen & DiTiberio, 1984. p.290).

Thinking versus feeling is defined as how people make decisions and arrive at conclusions. Although thinking types follow rational principles by trying to reduce the impact of any subjective factors, feeling types are guided by concern for others and for social values. Finally, judging versus perceiving is defined as how people prefer to deal with the outer world and act. Judging types like planning and order, whereas people on the perceiving end of the scale like flexibility and often resist the efforts of others to impose order on their lives (Dörnyei, 2005). Similarly, the judging types “tend to structure the outer world in a way that will lead them to get things done. They select projects that can be completed and formulate problems in a way that will enable them to be solved” (Jensen & DiTiberio, 1984, p. 294).

Many studies have reported the results of the relationship between personality types and other variables. Busch (1982) studied the relationship between English proficiency and extroversion-introversion among EFL students in Japan and rejected the hypothesis that extroverts were more proficient than introverts. Ehrman and Oxford (1995) used the MBTI and reported more advantages for introverts, intuitives, feelers and perceivers, while they concluded that introverts, intuitives, and thinkers were better at reading. On the other hand, Dewaele and Furnham (2000) investigated the relationship between speech production and personality type, finding extrovert bilinguals were more fluent compared to introverts in stressful circumstances. Also, extroverts performed better in terms of pronunciation accuracy in another study by Hassan (2001).

Examining the correlation between learners’ personality types and their writing ability and between raters’ personality type and their rating procedure, Marefat (2006) reported sensing-intuition as the only aspect which showed significant effect across writing. Also, a correlation was found between raters’ personalities and their rating procedure. The correlation between the dimensions of extroversion-introversion and argumentative writing resulted in extroverts outperforming introverts (Layeghi, 2011). Interestingly enough, Mansouri Nejad et al. (2012) concluded that no significant correlation exists between personality types and writing ability.

Writing Anxiety

Writing anxiety has been defined as “subjective complex of attitudinal, emotional, and behavioral interaction which reinforces each other” (Daly & Miller, 1975, p.79). Also, Cheng (2004) has explained this term “as a relatively stable anxiety disposition associated with L2 writing, which involves a variety of dysfunctional thoughts, increased physiological arousal, and maladaptive behaviors” (p. 319). In fact, when the level of anxiety is high, being demotivated and having negative views are the results. For instance, Daud et al. (2016) found that low apprehensive students tend to achieve higher scores in composition courses than high apprehensive students. On the other hand, when Hassan (2001) measured the relationship between writing anxiety and self-esteem, the results turned out to be significantly negative. Also, the self-esteem of high apprehensive learners was reported to be lower. Less apprehensive students were discovered to write three times more words than highly apprehensive students who also make more spelling errors (Book, 1976). Similarly, Daly (1978) reported a significant relationship between apprehension and quality evaluations. In other words, the text quality of high apprehensive writers was worse than that of less apprehensive writers.

In general developing high levels of writing competency requires substantial effort (Richards & Renandya, 2002). In this regard, producing coherent and high-quality writing is considered a challenging issue, even for native speakers (Nunan, 2003). As Chastain (1988) argued, writing is more amenable to individual practice. It means that learners go through personalized trajectories in developing their writing competency, and their socio-affective statuses will affect the way they develop such competency. As Richards and Renandya (2002) state, many university students majoring in English courses find this skill difficult. This may be because of some affective and cognitive factors such as students' writing anxiety and personality types.

Sadeghi (2014) states that writing anxiety may be caused by cognitive, linguistic or affective factors. Affective factors include anxiety, which can be the result of something inborn related to students’ personalities. So, according to him, writing anxiety for students of English as a foreign language (EFL) could mainly be a function of lack of or low self-confidence in their language abilities, which could influence writing achievement negatively. As Cheng (2002) notes, even highly-competent EFL learners may not find themselves to be proficient writers and may experience levels of writing anxiety. Accordingly, many EFL learners may feel uneasy when they are going to do their writing tasks; even those who are successful with other language skills. When they want to write and express their ideas in written form, they face linguistic complexities, inadequate writing practice, lack of topical knowledge, fear of tests, fear of teachers' evaluation, negative feedback from their teachers and peers, and low self-confidence in writing performance and as a result, they may fail.

Therefore, many studies have investigated the relationship between writing anxiety and psychological variables, namely self-efficacy, metacognitive awareness, and emotional intelligence (e.g., Balta, 2018; Ho, 2016; Huerta et al., 2017; Jawas, 2019; Liu & Ni, 2015). Also, personality types have been investigated separately with the main focus on extroversion versus introversion (Dewaele & Furnham, 2000; Hassan, 2001). However, no study has examined the impact all these four personality types including extroversion/introversion (Dewaele & Furnham, 2000), sensing/intuition (Jensen & DiTiberio, 1984), thinking/feeling (Matthews et al., 2009), and judging/perceiving (Mansouri Nejad et al. 2012) on writing anxiety in a single analysis. As language learners might bring different personality types to the classes, research in this area is important for a better understanding with respect to the possible impacts of such characteristics on performances of students in writing instruction. Accordingly, this study aims to examine the relationship between all dimensions of personality types known as extroversion versus introversion, sensing versus intuition, thinking versus feeling, and judging versus perceiving and writing anxiety. More specifically, it aims to study whether any personality type has the potential to predict writing anxiety of the learners or not. As a result, these five research questions have been proposed:

- Is there a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners' Extroversion versus Introversion type and writing anxiety?

- Is there a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners' Sensing versus Intuition type and writing anxiety?

- Is there a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners' Thinking versus Feeling type and writing anxiety?

- Is there a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners' Judging versus Perceiving type and writing anxiety?

- Which personality type can act as a predictor of Iranian EFL learners' writing anxiety?

Methodology

Participants and setting

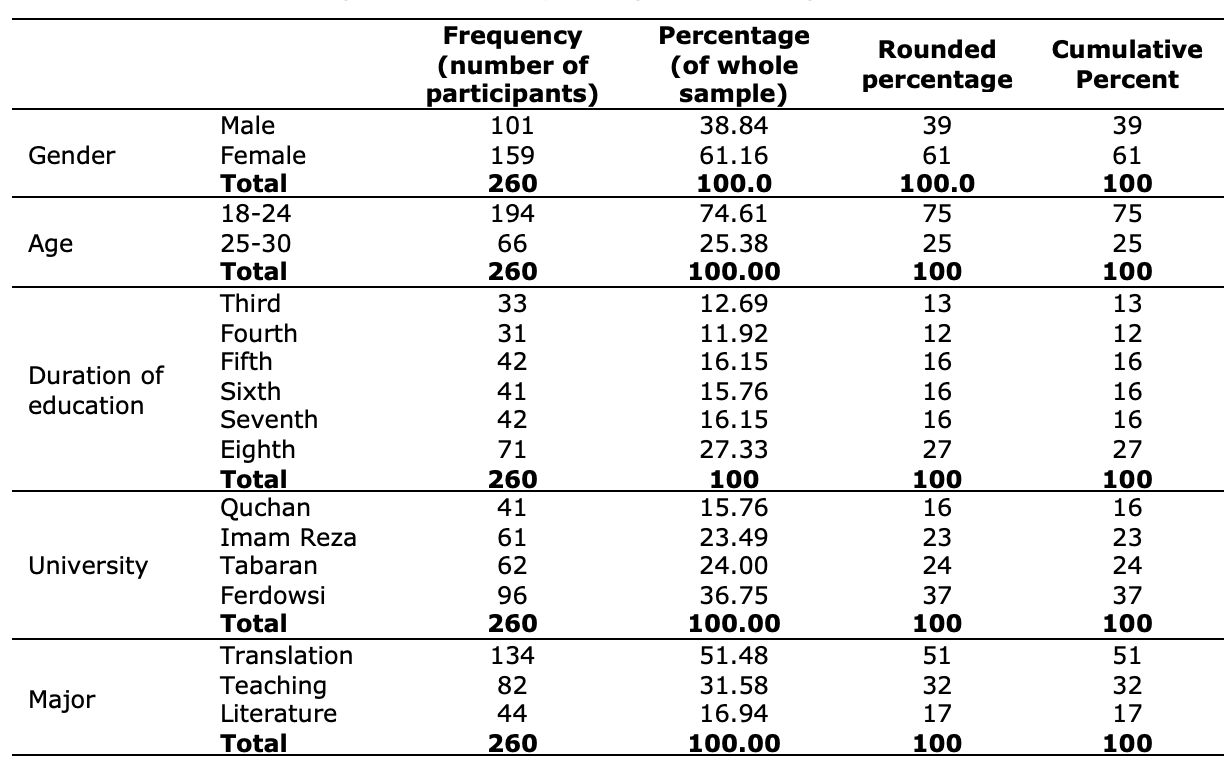

There are twenty-one university teaching fields related to the English language and with a capacity for 100 students in each university, the total population of this study was 2100. The required number of students to validate the sample size was 325 representing 95% of the confidence level and 0.05 degree of accuracy based on Morgan’ table (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970). However, the number of respondents who returned the questionnaires was 260 (101 males, 159 females). These students studied in several universities at the undergraduate level in the fields of English language teaching, translation, and literature (Table 1). Their age range was from 18-30 and they were selected by a non-probability sampling procedure (Dörnyei, 2007). It is worth mentioning that all the participants were native speakers of Farsi. In order to comply with ethical concerns, informed consent was obtained from the participants of the current study. Additionally, their anonymity was ensured in collecting data and reporting the findings.

Table 1: Demographic information of the participants

Instrumentation

In order to collect data from the participants of the study, two instruments developed in earlier studies were used.

Writing Apprehension Test (WAT)

Daly and Miller’s (1975) WAT was used to evaluate students’ apprehension in writing. Although this test has been designed for first language (i.e., mother tongue) writing students, Cornwell and McKay (2000) validated it for an English as a Second Language (ESL) context as well. It is a standard writing measure, which consists of twenty six items that feature thirteen items with positive polarity and thirteen with negative polarity. In fact, these items measure students’ reluctance to write, perceptions about writing tasks, and feelings as they write. The questionnaire was scored on a five-point Likert scale type with five choices ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree (Sarkhoush, 2013). The reliability of the WAT was calculated by split-half, Cronbach's Alpha, and test-retest methods. Daly and Miller (1975) reported the split-half reliability as 0.94 while the test-retest reliability over a week was reported to be 0.92.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

This questionnaire was selected because it has been regarded as the most valid and most widely taken personality style indicator (Kirby & Barger, 1998). In fact, although it was developed by Jung in the 1920s, its constructs were made explicit by Myers (1962). More specifically, this scale is regarded as Myer's interpretation of Jung's (1971) type theory. Kirby and Barger (1998) have referred to a wealth of studies providing “significant evidence for the reliability and validity of the MBTI in a variety of groups with different cultural characteristics” (p. 260). In the same vein, Murray (1990) examined the psychometric quality of the MBTI and cited its acceptable reliability and validity. As for the construct validity of this questionnaire, a number of researchers have confirmed the four factors predicted by the theory (Harvey et al., 1995). In fact, the results of confirmatory factor analysis of 94 MBTI items were performed, and its results supported the four-factor model. The MBTI, which consists of 70 self-report items, measures personality preferences along with four scales: Extroversion versus Introversion, Sensing versus Intuition, Thinking versus Feeling, and Judging versus Perceiving. This instrument has acceptable reliability and validity (Marefat, 2006).

Procedure

The participants were given two questionnaires, a writing apprehension test (WAT), and a questionnaire of personality scale (MBTI) which were translated into Farsi and were validated by two professors (both with doctorates in Teaching English as a Foreign Language). Also, in order to measure the reliability of WAT, the results of Cronbach’s Alpha turned out to be 0.85, while the reliability of MBTI was reported to be 0.81.

For collecting the required data, the researcher distributed the questionnaires to the previously described English language students in different institutes. Collecting data started in April, 2016 and lasted for about one month. It was determined that it would take about thirty minutes to fill out the questionnaire..

Data analysis

The data were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 24 for Microsoft Windows. To make sure that the research had prerequisites for parametric analysis, a test of normality was run. Since the purpose of this study was to investigate any significant relationship between the two variables of EFL learners’ personality types and their writing anxiety, four correlations were run to find both the direction and possible significance of the relationship between personality types and writing anxiety to determine which personality type can predict writing anxiety better. To this end, multiple regression analyses at a p-value of 0.05 were calculated. ANOVA was also conducted to evaluate the significance of the results and the beta coefficient was used to compare the strength of the effect of each individual independent variable to the dependent variable.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics

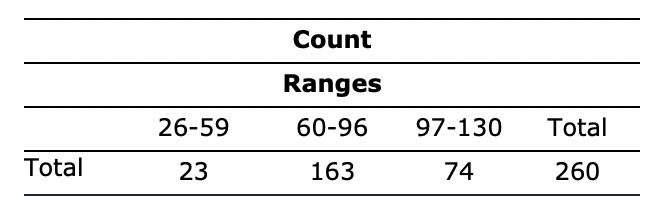

The results of descriptive analysis illustrate that twenty-three students had a low level of writing anxiety, 163 students had no anxiety about writing, and 74 students had high-level of writing anxiety (Table 2). Considering the range estimated by the questionnaire (60-96 = no anxiety, 97-130= low anxiety, 26-59= high anxiety), 81 respondents' scores in WAT questionnaire were 93 to 96 ranged from those with no anxiety, but they were very close to the score of high anxiety students. On the other hand, 32 respondents' scores were 60 to 63 whose range was in the second column, no anxiety, but they were very close to students with the low level of anxiety. Thus, because 113 respondents' scores wereclose to the low and high level of anxiety, it is possible that the number of respondents with no anxiety was more than other ranges.

Table 2: Cross tabulation for WAT

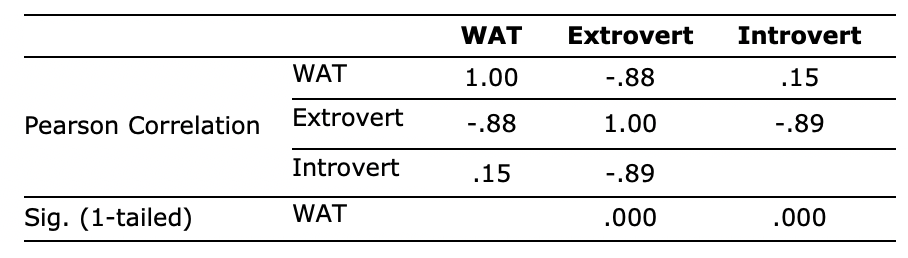

The first research question

The first question investigated the possible relationship between extroversion versus introversion and students' writing anxiety. Table 3 shows that the relationship between extroversion and writing anxiety is negative but significant (-.88). Based on these results, the more extroverted the learners are, the less they experience writing anxiety. On the other hand, the relationship between introversion and writing anxiety is positive and significant (.15). This means that the more introverted the learners are, the more writing anxiety they have. This finding is in line with Layeghi (2011) who found that extroverts had better writing performance than introverts. As anxiety impacts writing quality, it seems that this personality type is associated with experiencing lower levels of anxiety in writing that contributes to improved writing performance. Another explanation for these findings might be that extroverts are action-oriented and they tend to act more than reflect and seek to develop the breadth of their knowledge through communication (Matthews et al., 2009). They rely on trial and error to develop clear ideas about their world (Ehrman & Oxford, 1995). However, the findings of the current study are in contrast to Mansouri Nejad et al. (2012) who found no significant relationship between personality types and writing anxiety and performance. These differences might be resulted from a number of factors such as instruments employed and sample sizes investigated in the present study and that of Mansouri Nejad et al. Accordingly, there is a need for additional research in this area for obtaining a more transparent picture with respect to the impacts of personality traits and writing anxiety and performance.

Table 3: Correlation for personality type 1 (extroversion-introversion) and WAT

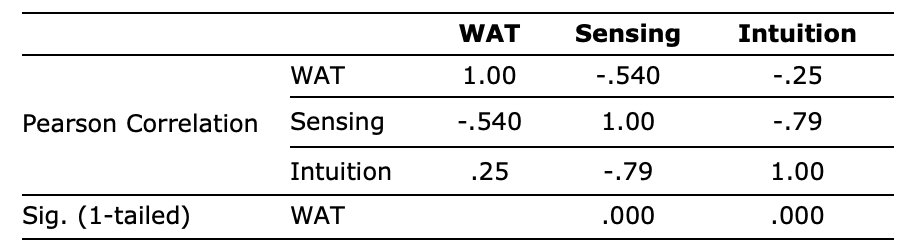

The second research question

The second question of the study examined the relationship between the learners’ sensing versus intuition type and their writing anxiety. Considering this question, the correlation table (Table 4) shows that there is a positive (.54) and significant (.000) relationship between the sensing factor and writing anxiety. On the other hand, the correlation between intuition and writing anxiety is negative (-.79) and significant (.000). This means that the more the learners rely on their intuition, the less they have writing anxiety. According to Jensen and DiTiberio (1984), intuitives, in general, have less difficulty with writing than sensing-type individuals. Because intuitive people go further to use all their capabilities, both sensing and intuitive functions, such as impression, abstract words and phrases. They grasp between-line meanings and produce ideas almost automatically and with little problems, connecting the ideas together more easily.

Table 4: Correlation for personality type 2 (sensing–intuition) and WAT

The third research question

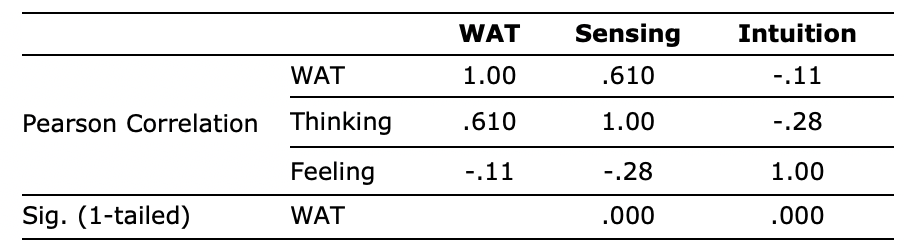

The third question investigated the relationship between the learners thinking versus feeling type and their writing anxiety. Table 5 shows a positive (.61) and significant (.000) relationship between thinking type and writing anxiety. However, there is a negative (-.28) and significant relationship between feeling and writing anxiety which means that when students think more, higher level of writing anxiety is the result. According to Jensen and DiTiberio (1984), thinking-type students usually engage their mind analytically and organize the ideas into neat structures; when presented with writing assignments that contain an unclear and non-logical standards they may perceive the writing as of low academic relevance.

Table 5: Correlation for personality type 3 (thinking–feeling) and WAT

The fourth research question

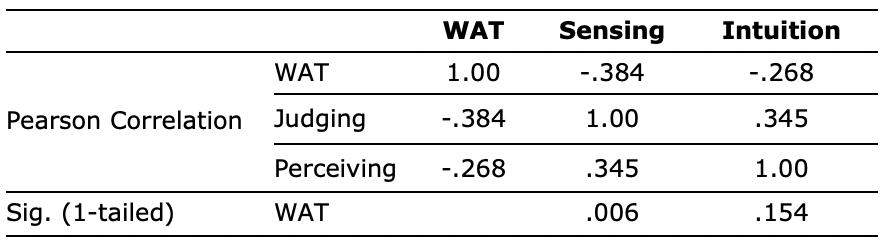

The fourth research question investigated the correlation between judging versus perceiving types of MTBI questionnaire and writing anxiety. Table 6 shows that the association between judging type and writing anxiety is negative (-.38) as well as its relationship with perceiving type (-.26), but the former type has a significant association (.006) while the latter one does not (.15). According to Jensen and DiTiberio, (1984) Judging type individuals attempt to structure their surroundings in a way that lead them to fulfil their purposes. Additionally, they go for projects that could be accomplished, pose problems that empower them, and focus on tasks inasmuch as they are completed. In this sense, judging types tend to limit their topics quickly and set goals that are manageable.

Table 6: Correlation for personality type 4 (judging–perceiving) and WAT

The fifth research question

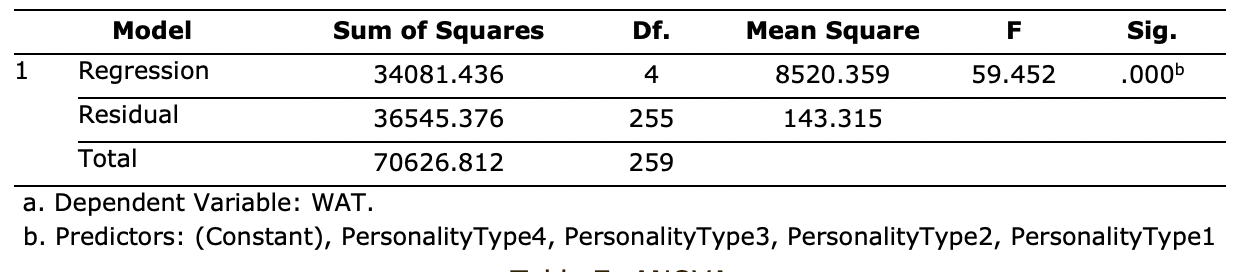

The fifth research question deals with the prediction of the factor which has the strongest relationship with writing anxiety and can best predict the success and failure of this variable according to one of the personality dichotomies mentioned in the MBTI questionnaire. To examine the significance of the results, it was necessary to look at Table 7 labeled Analysis of Variance (ANOVA.) This analysis is not only a basis for tests of significance, but also provides information regarding variability within a regression model. This table tested the hypothesis that multiple R in the sample equals zero. The model reached statistical significance (F = 10.82, Sig = .000). The order of Personality types 1-4 is as follows: 1. Extroversion versus introversion, 2. sensing versus intuition, 3. thinking versus feeling, and 4. judging versus perceiving.

Table 7: ANOVA

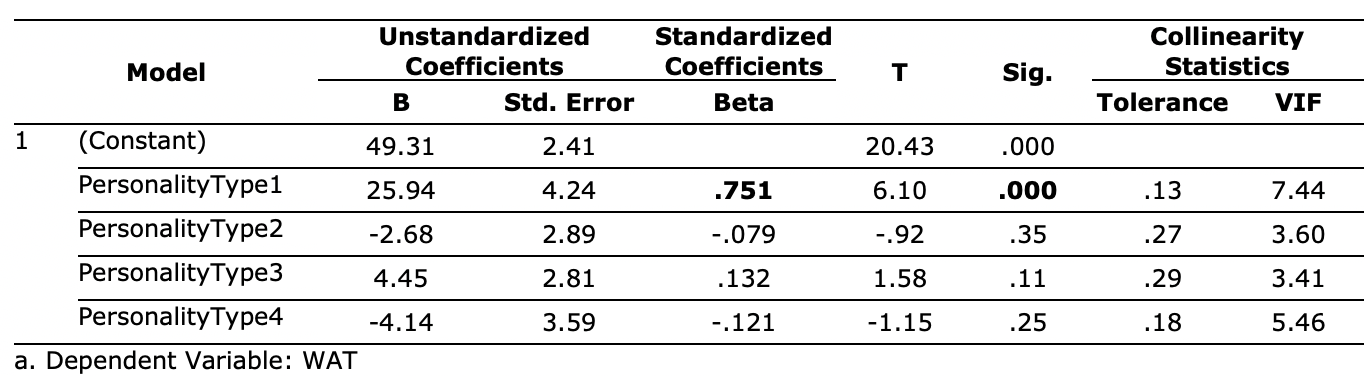

To know which of the variables included in the model contributed more to the prediction of the dependent variable, Beta was checked.

Table 8: Coefficients

As shown, the largest beta degree was .75, which was for personality type 1 (Extroversion versus Introversion) (Table 8). This means that this variable largely defined the dependent variable when the variance accounted for by all other variables was controlled. The Beta value for the other variables (i.e., other personality types) was not significant since the Sig values for the group were more than .05 so that they had little role in predicting the dependent variable. Therefore, personality type 1 was found to be the higher predictor of Iranian EFL students' writing anxiety.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the possible relationships between any of four different dichotomies of personality types which are extroversion versus introversion, sensing versus intuition, thinking versus feeling, and judging versus perceiving and writing anxiety. Data analyses showed that extroversion, intuition, feeling, and judging types had significant negative correlations with writing anxiety, which means that the more the students were oriented towards those personality types, the less their writing anxiety were. Furthermore, introversion, sensing, and thinking had significant positive relationships with writing anxiety. Among all personality types, it was only the perceiving type that did not have a significant relationship with writing anxiety.

Another major purpose of the present study was to find which of these pairs can best predict students' writing anxiety. Based on the results, the findings are that extroversion versus introversion had the highest standardized Beta coefficient (.75) and extroversion was reported to be the strongest factor, based on which it is possible to predict learners’ writing anxiety. Also, this variable had a negative correlation with writing anxiety (-.88).

The findings of the study have some implications for language teachers and foreign language writing instruction. First, language teachers need to have an enhanced understanding with respect to their students’ personality types and characteristics. Although such undertaking is not easily attainable, this awareness can provide better learning opportunities and tune up their classroom tasks as well as consequent assessments. Second, the findings of the current study suggest that extroversion is regarded as an important factor for learners to have lower writing anxiety. Thus, teachers can use this finding to justify their home- and class-work to ask for writing practices for those students with extrovert personality type. Relatedly, there is a need for designing (or adapting) language learning materials for facilitating writing competence development for other personality types. Third, based on personality types and the nature of writing that usually creates a lot of stress for the learners, specifically during the examination time, syllabus designers can have comprehensive knowledge and implement it in the syllabi to cover students with various types of personalities and prepare them with enough samples of writing in their materials to reduce the role of stress in their writing performance.

The present study had some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as it is the case with most online surveys, the return rate for the online questionnaires was less than required sample size. Although around 260 participants (around 80%) returned their responses, this issue should be accounted for in generalizing the findings. Second, with respect to sampling, the present study used convenience sampling procedure that might have resulted in biased responses. Additionally, using quantitative methods for investigating complex issues such as the impact of personality type on writings anxiety provides us with a partial picture of the complex reality, and consequently there is a need for using a more triangulated approach incorporating both quantitative and qualitative measures to understand the relationship. The current study also provides a number of suggestions for further research. First, the role of gender is not considered in this study; so it is possible to segregate the respondents according to their gender and analyze the data regarding this variable. Second, this study was conducted in an EFL context; so considering other contexts whose members have the chance to communicate in English outside the classroom environment more frequently and see how other productive skills like speaking can be treated with regard to anxiety are worth more consideration.

References

Balta, E. (2018). The relationships among writing skills, Writing anxiety and metacognitive awareness. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(3), 233-241. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n3p233

Book, V. (1976). Some effects of apprehension on writing performance [ED132595]. ERIC. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED132595.pdf

Boroujeni, A. A. J., Roohani, A., & Hasanimanesh, A. (2015). The impact of extroversion and introversion personality types on EFL learners' writing ability. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(1), 212-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0501.29

Busch, D. (1982). Introversion-extraversion and the EFL proficiency of Japanese students. Language Learning, 32(1), 109–132.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1982.tb00521.x

Chastain, K. (1988). Developing second-language skills: Theory and practice. Harcourt.

Cheng, Y.-S. (2004). A measure of second language writing anxiety: Scale development and preliminary validation. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(4), 313-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2004.07.001

Cheng, Y.-S. (2002). Factors associated with foreign language writing anxiety. Foreign Language Annals, 35(6), 647-656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2002.tb01903.x

Cornwell, S., & McKay, T. (2000). Establishing a valid, reliable measure of writing apprehension for Japanese students. JALT Journal, 22(1), 114-139. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ22.1-6

Daly, J. A. (1978). Writing apprehension and writing competency. The Journal of Educational Research, 72(1), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1978.10885110

Daly, J. A., & Miller, M. D. (1975). Apprehension of writing as a predictor of massage intensity. The Journal of Psychology, 89(2), 175-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915748

Daud, N. S. M., Daud, N. M., & Kassim, N. L. A. (2016). Second language writing anxiety: Cause or effect? Malaysian Journal of ELT Research, 1(1), 19.

Dewaele, J.-M., & Furnham, A. (2000). Personality and speech production: A pilot study of second language learners. Personality and Individual differences, 28(2), 355-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00106-3

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Routledge.

Dwi Wulandari, S.S., M.A. (2010). The correlation of personality and anxiety with the result of English learning. Proceeding of CLaSIC 2010. 2-4 Dec 2010, Singapore.

Ehrman, M. E., & Oxford, R. L. (1995). Cognition plus: Correlates of language learning success. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 67-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05417.x

Funder, D. C. (2007). Beyond just-so stories towards a psychology of situations: Evolutionary accounts of individual differences require independent assessment of personality and situational variables. European Journal of Personality, 21(5), 599-601.

Harvey, R. J., Murry, W. D., & Stamoulis, D. T. (1995). Unresolved issues in the dimensionality of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(4), 535-544. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164495055004002

Hassan, B. (2001). The relationship of writing apprehension and self-esteem to the writing quality and quantity of EFL university students. Mansoura Faculty of Education Journal, 39, 1-36.

Ho, M.-C. (2016). Exploring writing anxiety and self-efficacy among EFL graduate students in Taiwan. Higher Education Studies, 6(1), 24-39. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v6n1p24

Huerta, M., Goodson, P., Beigi, M., & Chlup, D. (2017). Graduate students as academic writers: Writing anxiety, self-efficacy, and emotional intelligence. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), 716-729. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1238881

Jawas, U. (2019). Writing anxiety among Indonesian EFL students: Factors and Strategies. International Journal of Instruction, 12(4), 733-746. https://www.e-iji.net/dosyalar/iji_2019_4_47.pdf

Jensen, G. H., & DiTiberio, J. K. (1984). Personality and individual writing processes. College Composition and Communication, 35(3), 285–300. https://www.jstor.org/stable/357457

Jung, C. G. (1971) Psychological Types. Princeton University Press

Kirby, B., & Barger, A. (1998). Personality: Theory and research. Consulting Psychology Press.

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607-610.

Layeghi, F. (2011). Form and content in the argumentative writing of extroverted and introverted Iranian EFL learners. Iranian EFL Journal, 7(3), 166–183.

Liu, M., & Ni, H. (2015). Chinese university EFL learners' foreign language writing anxiety: Pattern, effect and causes. English Language Teaching, 8(3), 46-58. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n3p46

Mansouri Nejad, A., Bijami, M., & Ahmadi, M. R. (2012). Do personality traits predict academic writing ability? An EFL case study. English Linguistics Research, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v1n2p145

Marefat, F. (2006). Student writing, personality type of the student and the rater: Any interrelationship? The Reading Matrix, 6(2), 116-124.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2009). Personality traits. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, J. D. (2007). Personality: A systems approach. Allyn & Bacon.

Murray, J. B. (1990). Review of research on the Myers-Briggs type indicator. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 70(3-suppl), 1187-1202.https://doi.org/10.2466%2Fpms.1990.70.3c.1187

Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Manual. Educational Testing Service.

Nunan, D. (2003). Second language teaching and learning. Heinle & Heinle.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge University Press.

Sadeghi, B. (2014). On the relationship between writing apprehension, personality traits, strategy use, and writing accuracy across proficiency levels [Unpublished masters thesis], Imam Khomeini International University.

Sarkhoush, H. (2013). Relationship among Iranian EFL learners’ self-efficacy in writing, attitude towards writing, writing apprehension and writing performance. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(5), 1126-1132. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.5.1126-1132

Stern, H. H. (2010). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Wilz, B. (2000). Relationship between personality type and grade point average of technical college students. [Unpublished masters thesis], University of Wisconsin-Stout. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/39781

Zhang, L. J. (2001). Exploring variability in language anxiety: Two groups of PRC students learning ESL in Singapore. RELC Journal, 32(1), 73-91. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003368820103200105