Introduction

Like most countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Thailand considers English language proficiency as an important contributory factor in human resource development and, consequently, national economic development (Ministry of Education, 2008). This philosophy has been prevalent in several discussions of language education policy in the country since the 1990s, and it has been growing over the ensuing years (Nakhonthap, 2003). Since the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015, English has become the working language in Thailand (Baker & Jarunthawatchai, 2017). However, Thailand’s poor standards in English when compared to its ASEAN neighbours are a source of continuing concern and are thought to hamper the country’s ability to compete in the regional and global economy (Ashworth, 2020; Kaur et al., 2016). Acknowledging the important role of English in facilitating international trade in goods and services as well as providing access to scientific knowledge, the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Thailand has sought to improve English language teaching (ELT) at all levels through a wide range of efforts, initiatives, national policies, and education reforms (Darasawang, 2007; Perez-Amurao, 2019). Improving the teaching of English is seen as a priority to raise the country out of the ‘middle-income trap’ and enable it “to move up the value-added ladder to a more knowledge-based economy” (Sondergaard, 2015, p.8). Through many national English language policies and programs (International Schools, Bilingual Program, International Program in Higher Education, Road Map for Education Reforms, Establishment of Support Organizations, Distance Learning and Self-Access Learning Center), the Basic Education Core Curriculum (BEC) 2008 (Ministry-of-Education, 2008) shows MOE’s great effort and willingness to improve ELT. As stated in BEC, English is a mandatory subject for the entire basic education core curriculum from Prathomsuksa 1 (P1) to Matayomsuksa 6 (M6), equivalent to Grade 1 to Grade 12. With the focus on learning English as a foreign language (EFL), and for communication, BEC emphasizes the development of learners’ communicative competence in all four language skills, which enables them to exchange and present data, and information, express their feelings, opinions, concepts and views on various matters. Besides, BEC also specifies the achievement of various communicative functions in speaking, and writing expected by the end of P3, P6, M3 and M6 (Grades 3, 6, 9 and 12, respectively). Teaching methodologies, with a preference for Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) and with an emphasis on the cultures of native speakers and Thai, are also recommended in BEC (2008).

Nevertheless, irrespective of the continuous and extreme efforts by BEC, Thai students’ levels of English proficiency tend to be far from satisfactory. As shown in the summary report of the Ordinary National Education Test (O-NET), their English language proficiency was low (National Institute of Educational Testing-Service, 2018a, 2018b). Furthermore, according to the Education First English Proficiency Index, in 2019 Thailand was ranked 74 out of 100 with a “very low” proficiency score (Ashworth, 2020). Also, the report from the TOEFL iBT score-summary in 2017 by Educational Testing Service showed that the mean score of Thai test-takers was lower than many of the test takers whose first languages (L1) are other than Thai (Educational Testing Service, 2017). Several reasons were blamed for the failure to improve scores on these tests. These include teachers’ continued reliance on outmoded grammar-translation, rote-memorization, and teacher-centered methods of teaching instead of the CLT approach prescribed in the core curriculum and emphasis on the receptive skills of listening and speaking (Darasawang, 2007; Wongsothorn et al., 2002). Besides the fact that the Thai language is used as the main language of instruction for every subject, including English, another significant cause for Thai’s low English test scores was the assessment system (Darasawang & Todd, 2012; Kaur et al., 2016). Indeed, almost every English class, including the English-speaking class in Thailand, used multiple-choice tests. The national tests to measure the English proficiency levels of Thai students were also multiple-choice, testing only grammar and reading. These indicate the deviation from the set goal of implementing a CLT approach to develop students’ communicative competence as prescribed in BEC 2008 (Ministry of Education, 2008). Furthermore, it is also known that there is a wide gap in the academic achievement levels of students in urban and rural communities in Thailand (Lathapipat, 2018; Mala, 2016). This could be due to the decentralization policy, which allows schools to create their curricula and teaching materials (National Education Act, 2010 ). While some schools actively responded to this policy by developing specialized English programs for improving students’ language skills, the majority of schools, especially those in rural areas, seem to face difficulties because of not having resources and qualified teachers to design effective courses and materials. This results in “a hotchpotch of poorly designed curricula with no relation to any other policies” in ELT in the country (Darasawang & Todd, 2012, p. 213).

With these thorny issues in ELT in Thailand, the present study explores how English language skills are taught at basic educational levels. However, within the scope of this paper, only the curriculum, teaching and learning of writing at upper-secondary schools (U-SS) (M4, M5 and M6, equivalent to Grade 10, 11 and 12, respectively) in the Northeastern part of Thailand are reported. The writing skill was first selected for investigation because it is one of the most difficult skills for students to develop, especially multilingual ones (Hyland, 2004). Moreover, as commonly documented in the literature of ELT in Thailand, the writing ability of Thai students is of particular concern. It is because the traditional teaching approaches which emphasize the accuracy of grammatical structures and vocabulary are commonly employed in English classes (Chamcharatsri, 2010; Nguyen, 2018, 2019; Puengpipattrakul, 2013; Srichanyachon, 2011). In addition, most EFL writing programs in the country focus on objective-type questions with the tasks of correcting errors, completing and reordering words and sentences in their formative tests (Darasawang & Todd, 2012; Wongsothorn et al., 2002). Therefore, students have very few actual opportunities to express their ideas and knowledge in writing in English. More recently, Nguyen (2018) found that Thai university students had difficulties in organizing their ideas in English. In fact, in their essay composition, Thai language was employed in their planning stage while Google Translate or Thai-English dictionaries were used to write up their essays. Furthermore, some students even mentioned being stuck when they wrote in English if teachers asked them to focus simultaneously on the ideas and organization of the writing. These practical problems have been thus reported to challenge the government’s plans stated in BEC in improving each communicative language skill of Thai students. With the decentralization policy and these documented problems on Thai students’ writing, this study aims to find out 1) what the English-writing curriculum at Thai U-SS in the Northeastern part of Thailand is like and 2) how English-writing is taught and learnt at Thai U-SS in the region. The findings of this study are hoped to provide a general picture of the teaching and learning of this skill and yield some empirical insights for improving its teaching and learning practices at U-SS levels in Thailand.

Methods

Research instruments

The research instruments employed in this study included two sets of questionnaires, classroom observations, actual test-paper reviews, and semi-structured interviews. With two parts of both open-ended and 5-point Likert-scale items, the two questionnaires were mainly used to obtain the information from teachers and new U-SS students for the stated research objectives. Section 1 included open-ended questions which planned to gain a general view of the English curriculum at U-SS while 5-point Likert-scale items in section 2 focused on how English writing was taught and learnt. In particular, 13 open-ended questions in section 1 of the teachers’ questionnaire aimed to get the information about teachers’ age, gender, degrees, the grades (M4/M5/M6) they taught, English courses at their schools, English textbooks used for each grade, the numbers of hours per week allocated for English subjects for each grade and a description of their regular English tests with a focus on the writing sections. Besides thirteen 5-point Likert-scale items (Table 1) to describe how teachers taught English writing, Section 2 included one open-ended question for teachers to add their ways of teaching the skill of writing if those were not listed in the survey. In the student questionnaire, the first section also gathered general information about them and a description of the regular English tests with a focus on the writing parts. The second section (Table 1) was designed for them to show their agreement or disagreement on how they were taught English-writing at their U-SS. This part was followed by an open-ended question for them to describe other different ways they learnt English-writing but were not listed in the survey. These two questionnaires were written in both English and Thai to ensure the participants’ understanding and provide proper answers to each question. In the open-ended questions section, participants were also allowed to write their responses in Thai. To clarify the findings from the questionnaires, classroom observations, actual test paper reviews and semi-structured interviews with teachers, students, and PS were also conducted. To obtain students’ and teachers’ permission and consent for the researchers to observe their classes, review their test papers, and interview, the two researchers contacted them personally via their contacts provided in the returned questionnaires. Ten teachers (T1-T10) from ten different schools allowed for classroom observations and interviews, and each provided two actual test-paper reviews (20 test papers in total). Furthermore, 29 students (S1-S29) of twelve schools and two PS (PS1-2) agreed to have the interviews. The interviews were carried out in the Thai language for the participants to express themselves thoroughly.

Participants and data collection

The two questionnaires had the intentions to reach the purposes, the subject matter of the research, and the researchers’ contacts, and highlighted the voluntary participation of the participants. Before sending the questionnaires to the teacher and student participants, formal connections were established with five PS who took care of foreign language education of U-SS of different provinces in the Northeastern part of Thailand (considered as rural communities in Thailand). The research purposes and the procedures to be undertaken to complete the surveys were explained to them in detail. These five PS helped to deliver these two questionnaires to U-SS English teachers who then sent the questionnaire to new graduates of U-SS of ten provinces in the region. The consent form was included at the beginning of the questionnaires, where the participants read and signed before they answered the surveyed questions. Furthermore, the student participants were U-SS graduates who were older than 18 years old, this study did not involve their parental consent in the process. There was a total of 189 teachers and 256 students from 74 schools who returned their questionnaires, but only 114 teachers and 170 students completed all items in the questionnaires. This study, therefore, employed only the completed responses from 114 teachers and 170 students to address the two research objectives.

Data analysis

The open-ended responses (Section 1) in each questionnaire were first translated, triangulated, and finally tabulated by calculating the total numbers of similar answers to the same question to have a general view of the English curriculum at U-SS in the region. To explore how English writing was taught and learnt, the SPSS software (version 21) was employed to determine the means scores of each Likert-scale surveyed item. The ways to teach and learn EFL writing described in the open-ended questions (in Section 2 of the questionnaires) were first read and classified into themes, and the theme classification was then employed to provide more information to the findings from the surveys. Then, the statistics (means) and descriptions from both teachers and students were interpreted to have a general view of EFL writing classrooms at U-SS in the region.

The relevant information from classroom observations, test-paper reviews, and semi-structured interviews with the participants was translated into English and included in the previously mentioned discussion to provide an insightful understanding of the findings.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the findings on the English curriculum at U-SS in the Northeastern part of Thailand in terms of the English courses, textbooks, weekly teaching hours, and writing tests. How EFL writing was taught and learnt will follow in the next section. The information from the interviews, test-paper reviews, and classroom observations isadded in the text where clarification is needed to shed more light on the findings

English Courses

As can be seen in Figure 1, Basic English is the main course taught at all levels (M4, M5, and M6) in 64, 61 and 62 (out of 74) U-SS in the region, respectively. English Conversation, the second most frequently taught course, was reported by teachers in 20, 15 and 17 schools for all three levels. Integrated Reading and Writing came third as it was taught in eleven, nine, and eight schools for M4, M5 and M6, respectively. Few schools taught other subjects, including English for Occupations and Tourism, Critical Reading, and English Translation for M5, and M6 students. This tends to indicate that most schools taught basic English while, as compared with Reading and Writing, English Conversationwas taught in more schools.

Figure 1: English courses at Thai U-SS

In the interviews with two Provincial Supervisors (PS1-2), it was discovered that schools had the freedom to develop their English courses to suit their contextual characteristics, as guided by Ministry-of-Education (2008), However, the courses needed to meet the basic requirements in terms of learning hours, learning objectives and learning outcomes prescribed in the core curriculum. Also, they also mentioned that though the course names and the numbers of courses were different among schools depending on their conditions, all schools had to have at least one basic-English course as a compulsory subject as indicated in BEC (2008). The basic-English course could be incorporated in either English Conversation, Reading and Writing, or any English courses. This information was further certified by the teachers (T1, T4, and T7) in the interviews when they said that they taught students basic English in their English Conversationcourse. Most interviewed teachers confirmed that the names of the courses were chosen by their schools’ academic committee.

Textbooks

Different from the limited English courses, 23 different textbooks were selected to use for three levels at 74 U-SS in the region (Figure 2). Among them, New World was most selected to teach students at all levels (in almost half of the schools), followed by Eyes Open and My World. Other textbooks were used by a couple of schools for their specific courses (e.g., Fifty-Fifty for English Conversation and Reading Adventure with Writing for Reading and Writing). The two PS also mentioned in the interview that these books were published by Cambridge, Oxford, McGraw Hill, and Longman and selected from a list of textbooks recommended by the Ministry of Education (2008). These books reach the MOE’s objectives to develop learners’ communicative competence in all four language skills, as prescribed in BEC (Ministry of Education, 2008). However, to have a reasonable price for Thai students, Thai publishers bought the copyright of the books and reprinted them in Thailand with only the preface translated into Thai, and the main contents of the books were in English.

Figure 2: English textbooks used at Thai U-SS

Another interesting finding is that a considerable number of schools (18, 17, and 16) employed teacher-designed materials for M4, M5, and M6, respectively. As revealed by some teachers (T3, T9, and T10) who reported using their materials to teach English, it was known that these materials were compiled from other textbooks or internet sources and delivered to students as worksheets and handouts to study in class. This finding agreed with the decentralization policy by Office-of-the-National-Education-Commission (2010), which authorizes schools to develop and use their teaching materials.

Weekly Teaching Hours

In general, most schools had two to four hours for students of all levels to learn English while a small number of schools had five or six hours (See Figure 3). As reported by teachers (T3, T6, and T10), the number of hours higher than two indicated that their schools had more than one English course. In other words, besides two hours of basic English as required by MOE (Ministry of Education, 2008), the schools had extra courses such as Reading and Writing, English for Occupations and Tourism and English Translation for their students to improve their English. However, it was surprising to know that about 12% of schools (11, 9, and 8) did not have English classes for M4, M5 and M6, respectively. As revealed by the teachers, it was because their schools focused on occupational and technological courses (T1, T4, and T7), and sometimes the schools did not have English teachers (T5 and T9). The two PS further clarified this unexpected finding by stating that, as compared to the curricula for primary and lower secondary-schools, the BEC requirements for the U-SS curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2008) are more flexible. In particular, U-SS are granted full authority to design their curriculum depending on their contexts, readiness and focus. They are also allowed not to have English subjects or replace English with other foreign languages (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese) if their schools do not have English teachers. Whenever their curriculum is approved by the school committee, it is implemented right away without any validation by external organizations.

Figure 3: The number of hours English is taught at Thai U-SS

Emphasis on Teaching EFL Writing at Each Grade

In answering the question in the teacher questionnaire about in which grade (M4, M5, and M6) teachers focused more on teaching EFL writing, 88 out of 114 (77.2%) reported that they taught this language skill equally to students of each grade. A small number of teachers (16, 6, and 5) said their emphasis on teaching the writing skill was separately placed on M6, M5, and M4, respectively. However, the students’ responses to the question of which grade they studied EFL writing in were diverse. As seen in Figure 4, more than half of 170 students reported that they practiced the writing skill a little at all grades and around a third of them said they practiced this skill a lot in each grade as can be seen in Figure 4. 15.9% of students even reported they did not practice this skill in M4 whereas 7.6% and 8.8% mentioned no EFL writing was taught at their M5 and M6, respectively. In contrast, in the interviews with T2, T3, T5, T6, and T8, several reasons were given for their need to teach the writing skill to students of all levels. These included improving their English writing skills, preparing them for the O-NET, higher studies, and future careers. Moreover, some even stated that skill of writing should be taught at all levels as it was indicated in their school curriculum. Interestingly, while the importance of writing skills was also accounted for its being taught at all levels by these interviewed teachers, a couple of them (T1 and T7) mentioned the necessity of teaching writing was to consolidate students’ grammar and vocabulary.

Figure 4: Students’ report on the grades they learnt EFL writing the most

Writing Sections in Teachers’ Regular Tests

In responding to the question of whether the schools’ regular tests had a writing section, 108 teachers, accounting for 95% of the total, said “Yes”. Figure 5 describes the different weights given to the writing section by those teachers. 38 of them mentioned that the writing part accounted for 20% and 30% of the test score while 10% of weighted score for this section was reported by fourteen teachers. Responses varied between 5 and 50% in this section.

Figure 5: Percentages of scores for the writing section in teachers’ regular tests

These teachers also specified the types of writing in the tests they applied, as can be seen in Figure 6. Sentence completion and Filling the blanks were the two most common writing tasks, reported by 94 and 89 teachers (accounting for 82.5% and 78.1% of 108 teachers), respectively. Error identification and Error correction were listed by almost half of these teachers (49.1% and 45.6%, respectively), while 56.1% of teachers mentioned Writing a certain text type (e.g., paragraph, email, postcard), 34 out of 108 teachers (29.8%) indicated Writing an essay as a task type in the writing section of their regular tests at school. Rearranging words to make a complete sentence was also reported by two teachers (1.8%). The writing tasks in teachers’ regular tests described by the students, however, showed that the tests tended to focus more on objective-types of Filling the blanks, Error correction, Sentence completion, Error identification and Rearranging words to make a complete sentence with 98.2%, 81.6%, 72.4%, 50.6%, and 31.8%, respectively. The writing skill tests using Writing a certain text type and Writing an essay were reported by the smallest percentages of students (28.8% and 16.5%). In contrast, these components were described by more than half and almost a third of 108 teachers, respectively.

Figure 6: Types of writing in teachers’ regular tests reported by teachers and students

In reviewing 20 actual midterm and final tests administered by ten schools (two each), a similar finding to the report by Wongsothorn et al. (2002) was discovered. Objective-type questions of sentence completion, reordering sentences, reordering words, and error correction were present in most test papers while four tests had the task of writing a specific text type. As explained by the teachers whose tests included writing skills (T3 and T10), these two tests were used for students taking specialized English programs while the other tests were for general English classes. This could suggest that the writing skills of most U-SS students in the region were tested through objective-type questions.

How EFL writing was taught and learnt

To characterize how EFL writing was taught and learnt, the information obtained from teachers and students in the 5-point-Likert scale questionnaires, classroom observations and interviews was interpreted and is shown in this section. In general, the mean scores of most items were higher than 3.0 (Table 1), indicating the agreement from teachers and students to most surveyed items. However, it should be noted that despite their means score lower than 3.0, the three last items in the student survey (SS) turned out to confirm that EFL writing was taught in class (Items 6 and 7), and school tests had writing sections (Item 8). Similarly, with the mean scores of 3.02 and 2.92, items 11 and 12 in the teacher survey (TS) asserted that not all teachers skipped the writing lessons in the textbooks. This finding was supported by items 4 and 5 in SS and item 9 in TS when the students and teachers showed their agreement to these items with relatively high means scores (3.56, 3.43, and 3.30, respectively). For Item 13 in TS whose score was the lowest (2.67), teachers admitted in the interviews that though they gave students writing samples for most writing tasks in the textbooks (Item 4, TS), they did not ask them to learn by heart as they knew such writing tasks would not be included in either schools’ tests or national tests (O-NET).

Table 1: How EFL writing was reported to be taught and learnt in class

Furthermore, with the highest scores of 4.11 and 4.10 (Table 1), the first two items in SS tended to reveal that EFL writing was generally used for practicing grammar, reading, listening, and vocabulary exercises in class. This way of learning writing was validated by the second-highest means (3.89) of teachers’ agreement to “I focus on training my students with sentence transformation and grammar exercises” in TS. Moreover, although both teachers and students agreed that teachers always checked students’ writing (Item1, TS and Item3, SS), the interviews with students (S1, S12, S16, S20, and S28) showed that checking was done on their written answers to the tasks from grammar, reading, and listening lessons. Moreover, the high score of 3.72 for Items 5 and 6 in TS indicated that these teachers employed genre-based and process-based approaches, respectively, in teaching EFL writing. However, the information from all ten classroom observations of teachers’ teaching a writing lesson disclosed their ignorance of genre and process-based pedagogies. Though ten teachers were informed about the observation of their writing classes by the PS who took care of foreign language education in the province, four teachers taught “writing for learning” (Harmer, 2007, p. 31) because the writing was used to support their grammar teaching. This could indicate the influence of the grammar-translation instruction deeply entrenched in ELT in Thailand (Chamcharatsri, 2010; Hallinger & Lee, 2011). Employing the writing lessons from the textbooks on how to write a paragraph about a dream house or a favorite restaurant, a birthday-invitation email, a thank-you email, a web-blog and a postcard, the other six teachers demonstrated their teaching of “writing for writing” (Harmer, 2007, p. 34). Nevertheless, instead of helping students recognize the rhetorical structures and linguistic features used to accomplish the communicative purposes of the target genres or the several steps of brainstorming, drafting, editing, and revising in the process approach, these teachers made their writing lessons an extended grammar lesson. Because the key language structures for these target genres were summarized in the textbooks, students were asked to use them to write texts like the samples in the books alone or with their friends. While the interactive characteristics of CLT reported relatively high means scores of 3.44 and 3.25 (Items 8 and 10, TS, respectively) were presented in their actual classrooms, these teachers did not help students know the various conventions of different genres.

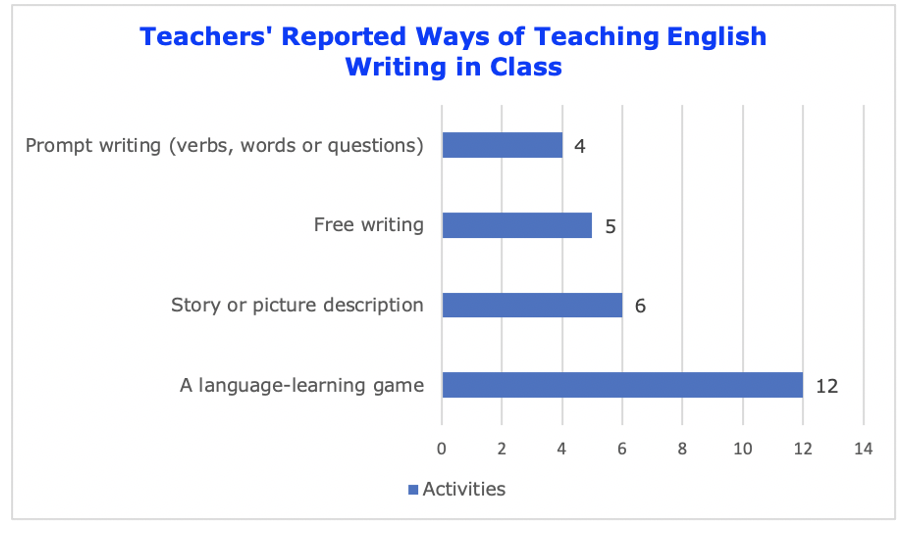

The final interesting finding from the surveys was from Item 7 (TS) “I use writing activities as fun activities in class”with a means score of 3.59. Although only 27 teachers shared their different ways or techniques of teaching EFL writing from those listed in the survey, 12 of them reported using writing as a language-learning game (Figure 7). Six of them employed stories or pictures for students to describe in writing while free writing and writing from prompts were also reported to be applied by five and four teachers, respectively. These details tend to reflect the enjoyment in EFL writing classrooms at Thai U-SS. Classroom observations also found teachers’ efforts in making their writing classes fun by not only organizing competitive activities for groups or pairs of students to participate in but also singing songs and watching short videos as warm-up activities; however, it seemed that they were not related to the teaching topics and learning objectives. Though, it is common for classrooms in Thailand to have fun and comfort (Baker, 2008;Nguyen, 2019), these activities were not suitable for an effective EFL writing class. Furthermore, though teachers believed that they “use relevant teaching activities to teach each specific writing topic/task in the textbooks” (Item 3, TS), with a mean score (3.76), what was observed in their classroom did not justify this situation. This finding is likely to suggest that these teachers would not have enough subject and pedagogical knowledge for teaching EFL writing.

Figure 7: Teachers’ reported ways to teach EFL writing in class

Regarding students’ self-report on how they were taught EFL writing, 32 students added four activities (Studying from online websites, YouTube, or social media, Taking a tutoring course after school, Reading a lot of different texts and Practicing writing very often) (Figure 8). However, these activities were not about how they learnt the writing skill in class but their extra-curricular activities. The interviews with them (S4, S7, S13, S19, S26, and S29) showed that they were not fully aware of learning the writing skill, and in-class they wrote in English what their teachers asked them to do. Besides, they also added that those who practiced and took tutoring courses for English writing were likely to have plans for overseas studies after graduation.

Figure 8: Students’ reported ways of learning EFL writing

Conclusion

Acknowledging the commonly reported problems about Thai students’ writing abilities and the decentralization policy in ELT in Thailand, this study explores the English curriculum and teaching and learning of EFL writing at U-SS in the Northeastern part of Thailand. The findings from two sets of questionnaires, classroom observations, reviews of test papers, and interviews with students, teachers, and PS showed diverse English curriculum designs, and the focus on teaching and learning simplistic and non-transferable knowledge in EFL writing classrooms at U-SS in the region. No systematic curriculum for English language education at U-SS, the mere teaching of grammar despite their objectives of teaching a specific writing genre, non-subject related learning activities and the prevalent presence of the objective-type questions for the writing sessions in the tests could be the main sources of Thai students’ chronic writing problems. As stated by Darasawang and Todd (2012), the foreign language education policy affects the teaching and learning process and the content to be taught. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Education (2008) has made great efforts to develop Thai students’ communicative competence this objective has not been reached mainly due to the power given to schools and teachers to make their own decisions for the English curricula at their schools (Darasawang & Todd, 2012). Besides the curricula, the findings from this study also indicated that it would be difficult to improve Thai students’ EFL writing abilities because of a lack of qualified teachers trained to teach EFL writing. Therefore, the suggestion by Baker and Jarunthawatchai (2017) on training teachers to bridge the gap between English education policy and ELT practice in Thailand should be implemented for the teachers in this project. These teachers need to have proper training in employing the CLT approach, which is required by Ministry of Education (2008) and designing relevant learning activities for the defined learning objectives. In English classrooms in Thailand, fun and enjoyment are necessary parts of teachers’ lessons. However, teachers tended to focus on these two elements without considering their appropriateness to the objectives of the target lessons.

Though this study was conducted in the Northeastern part of Thailand, its findings could provide policymakers, school administrators and U-SS teachers in the region, and other educational settings in Thailand some empirical information for their plans to improve the English curricula and the teaching and learning of EFL writing at U-SS levels. As reported in previous studies on EFL teaching and learning in Thailand (Baker, 2008; Hallinger & Lee, 2011), large classes, test-teaching orientation, teacher centeredness, and rote learning are still popular, and how to teach EFL writing properly is not yet documented. Therefore, future research on this topic in other teaching contexts in Thailand as well as in other countries with similar EFL teaching and learning practices is needed to improve the writing ability of EFL students.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our special thanks to Mr. Ifzal Syed for his considerable assistance, insightful comments and in-depth discussion on the findings which made it easy for us to complete this article

References

Ashworth, C. (2020, November 27). Thailand’s English level drops for the third year – English proficiency index. The Thaiger.https://thethaiger.com/news/national/thailands-english-level-drops-for-the-third-year-english-proficiency-index

Baker, W. (2008). A critical examination of ELT in Thailand: The role of cultural awareness. RELC Journal, 39(1), 131-146.https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688208091144

Baker, W., & Jarunthawatchai, W. (2017). English language policy in Thailand. European Journal of Language Policy, 9(1), 27-44. https://10.3828/ejlp.2017.3

Chamcharatsri, P. B. (2010). On teaching writing in Thailand. Writing on the Edge, 21(1), 18-26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43157412

Darasawang, P. (2007). English language teaching and education in Thailand: A decade of change. In D. Prescott (Ed.), English in Southeast Asia: Varieties, literacies and literatures (pp. 187-204). Cambridge Scholars.

Darasawang, P., & Todd, R. W. (2012). The effect of policy on English language teaching at secondary schools in Thailand. In E.-L. Low & A. Hashim (Eds.), English in Southeast Asia: Features, policy and language in use (pp. 207-220). John Benjamins.

Educational Testing Service. (2017). Test and score data summary for TOEFL iBT tests. Retrieved on 20 May 2021 from https://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/94227_unlweb.pdf

Hallinger, P., & Lee, M. (2011). A decade of education reform in Thailand: Broken promise or impossible dream? Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(2), 139-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2011.572868

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach writing (6th ed.). Pearson.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. University of Michigan Press.

Kaur, A., Young, D., & Kirkpatrick, R. (2016). English education policy in Thailand: Why the poor results? In R. Kirkpatrick (Ed.), English language education policy in Asia (pp. 345-361). Springer.

Lathapipat, D. (2018). Inequalities in educational attainment. In G. W. Fry (Ed.), Education in Thailand: An old elephant in search of a new mahout (pp. 345-372). Springer.

Mala, D. (2016). O-Net scores rise, students still failing. Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/905620/o-net-scores-rise-students-still

Ministry of Education. (2008). The basic education core curriculum B.E. 2551 (A.D. 2008). Ministry of Education. https://neqmap.bangkok.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Basic-Education-Core-Curriculum.pdf

Nakhonthap, A. (2003). Annual report of Thai education in 2003. Phappim Publishing.

National Institute of Educational Testing Service. (2018a). Summary of Ordinary National Education Test (ONET) for Matayomsuksa 3 in the academic year 2017. Retrieved on 20 May 2021 from http://www.newonetresult.niets.or.th/AnnouncementWeb/PDF/SummaryONETM3_2560.pdf

National Institute of Educational Testing Service. (2018b). Summary of Ordinary National Education Test (ONET) for Matayomsuksa 6 in the academic year 2017. http://www.newonetresult.niets.or.th/AnnouncementWeb/PDF/SummaryONETM6_2560.pdf

National Education Act (2010). B. E. 2542 of 1999, Revised B. E. 2545 of 2002, Revised B. E. 2553 of 2010. Krisdika [Unofficial translation]. http://web.krisdika.go.th/data/outsitedata/outsite21/file/NATIONAL_EDUCATION_ACTB.E._2542.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3Ysz_PlDAg_BENMvwxvm3M0rMRh20P8AM88TaVN5JAu30jP3FxQ9NMHWY

Nguyen, T. T. L. (2018). Reflections on modified genre-based instructions to teach essay writing to Thai university students. Asian EFL Journal, 20(9.1), 148-174.

Nguyen, T. T. L. (2019). Reflective teaching in an EFL writing instruction course for Thai pre-service teachers. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(2), 561-575. https://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.2.8.561

Perez-Amurao, A. L. (2019). Revisiting Thailand's English language education landscape: A closer look at Thailand's foreign teaching personnel demographics. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 1, 23-42. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3642420

Puengpipattrakul, W. (2013). Assessment of Thai EFF undergraduates' writing competence through integrated feedback. Journal of Institutional Research in South East Asia, 11(1), 5-27.

Sondergaard, L. M. (2015). Thailand – Wanted: A quality education for all. World Bank Group. Retrieved on 6 December, 2022 from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/941121468113685895/Thailand-Wanted-a-quality-education-for-all

Srichanyachon, N. (2011). A comparative study of three revision methods in EFL writing. Journal of College Teaching and Learning, 8(9), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v8i9.5639

Wongsothorn, A., Hiranburana, K., & Chinnawongs, S. (2002). English language teaching in Thailand today. Asia-Pacific Journal of Education, 22(2), 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/0218879020220210