Introduction

The outbreak of Covid-19 caused countries to take widespread measures including the implementation of school closures worldwide (Aquino, 2020), which meant a large-scale education cuts for an unprecedented number of students. In order to ensure the continuity of formal education and to compensate for interruptions at primary, secondary, high school and higher education levels, some institutions put innovative projects into practice. Those innovations also included emergency remote teaching practices (Basilaia & Kvavadze, 2020), which posed a transformative challenge for all. Like all other course contents, foreign language teaching has experienced difficulties both on sides of teachers and learners while moving to online education. Teachers did not have much time to redesign lessons, adapt materials and find engaging methods to create a rewarding teaching and learning environment for efficient language learning (Egbert, 2020). Emergency remote teaching applications during the pandemic affected language learners negatively due to the lack of face-to-face interaction and the sudden change of setting (Sepulveda-Escobar & Morrison, 2020).

Interaction plays a significant role not only in learning in general (Ahmad et al., 2017), but also in online education (Wright et al., 2015). Therefore, online language teaching processes should be designed carefully so as to improve learner interaction and productivity. An online intercultural exchange (OIE) activity, which might also be labeled as virtual exchange or telecollaboration, can be defined as instructionally mediated collaborative tasks that create opportunities for social interaction between language learners from geographically and culturally different places (O'Dowd, 2007; O'Dowd & Lewis, 2016). Emergency remote teaching practices due to the global pandemic are part of a relatively a new research area. Remote foreign language teaching and learning in these circumstances now has an emerging literature which requires more research in order to improve the teaching-learning processes. OIE between institutions of different cultural / national origins may have potential to enhance foreign language learning during the emergency conditions such as pandemics as they provide opportunities for communication for real purposes at a distance. Even though OIE in foreign language learning has been studied from different perspectives such as changes of feedback types (Feng et al., 2021), improvement of language comprehension, fluency and lexicogrammar (Saito & Akiyama, 2017), linguistic accuracy (Tudini, 2012), learner autonomy (Schwienhorst, 2008), very few studies examined the perceptions of learners in intercultural exchange activities when both sides were non-native speakers using the target language, English, as lingua franca. More importantly, there is a need for studies on OIE as an alternative to remote language teaching practice initiated during emergency remote teaching. In their study, Porto et al. (2021) initiated an OIE project between Argentinian and US undergraduates, in which the participants explored the theme of the COVID-19 crisis using English as their lingua franca. The authors suggested that experiences regarding pedagogies of discomfort in language classrooms in higher education are recent and rare. The authors claim that experiences of emotional discomfort emerging from difficult or traumatic experiences, like the COVID-19 crisis, should be addressed pedagogically. The current project focused particularly on this need and was initiated during the pandemic. Likewise, the findings of this study could shed light on the relevant literature by reporting by means of OIE, the firsthand experiences of language learners who were being affected by the COVID-19 crisis. In this way, it will be possible to make inferences about the role of OIE in creating interaction, engagement and motivation during remote language learning processes. In addition, connectivity and learner engagement in online learning environments were commonly emphasized during the pandemic (World Bank Education, 2020). In this context, OIE can be a timely and on-the-spot application for foreign language learners worldwide who have to switch to online learning.

Interaction in distance education and in foreign language learning

Educators have considered interaction as one of the most critical components of the education context and process (Anderson, 2003; Moore, 1989). Moore (1989) identifies a model of interaction made up of three categories, including learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner interaction. According to Anderson (2003), these three types of interaction are significant for a meaningful learning experience. According to Anderson's Equivalency of Interaction theorem, "deep and meaningful formal learning is supported as long as one of the three forms of interaction (student–teacher; student-student; student-content) is at a high level. The other two may be offered at minimal levels, or even eliminated, without degrading the educational experience” (Anderson, 2003, p. 4). From this perspective, OIE activity can enhance learner-learner interaction by bringing language learners together using different online communication tools.

Interaction is essential in foreign language learning (Loewen & Sato, 2018). Language was born as a necessity of social interaction and communication. The general purpose of language learning is to be able to use the target language fluently (without hesitation), accurately and effectively (without offending the recipient) (Ellis, 2003). The most effective way to achieve this is to create situations where students can experience real language environments in their foreign language learning processes. According to this view, the learning process that students experience is essential in language education. In this process, learners should be exposed to the target language in an interactive context and should be faced with problems that they can solve using the target language (Ellis, 2003). Likewise, according to the Interaction Hypothesis in the field of foreign language acquisition, input, interaction, feedback, and output play important roles in the learning process (Krashen, 1985, Long, 1996; Pica, 1998; Swain, 1985). The Interaction Hypothesis draws attention to positive correlation between interactionally modified input and language acquisition (Loewen & Sato, 2018). The hypothesis includes the interaction of input and output with students' cognitive resources in the processes of language exposure and language production (Pica, 2013). Language learners need to produce through both written and spoken communication in the target language. According to Ellis (2000), it is easier to process language input with an internal language acquisition mechanism, when the language learner has a low level of anxiety and high motivation. Therefore, activities like OIE, which provide opportunities for peer interaction and boost motivation while lowering anxiety, may create an optimum foreign language learning atmosphere.

Similarly, in Social Interaction theory, Vygotsky (1978) claims that the basic function of the language is the communication that takes place in the interaction process. It is suggested that the language acquisition level of an individual who learns a foreign language will improve with guidance and encouragement from a skilled partner whose language level is more advanced than himself, which is defined as Zone of Proximal Development. Learners become aware of their linguistic problems and structures that they do not know or know wrong with the production they make in a foreign language, that is, the output. This awareness can be achieved through production (Swain, 1995) in meaningful exchange activities. Briefly, constructing meaning in foreign language learning is both a cognitive and a social process (Watson-Gegeo & Nielsen, 2003).

Intercultural communicative competence

With the spread of information and communication technologies around the world, the number of non-native English speakers has increased. English is no longer a language limited to native speakers, but now it is used by speakers from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds with different language usage styles and functions (Seidlhofer, 2013). Also, English has become the medium of communication and instruction (Dearden, 2018) in computer mediated learning, e-learning, mobile learning, and most open and distance learning contexts. As one of the global scale studies, Dearden's (2015) survey on English-medium instruction (EMI) has shown that English-medium courses and programs in higher education are rapidly becoming widespread.

In the field of foreign language education, the significance of linguistic and communicative competence and also intercultural competence have been emphasized. Functionalist approaches prioritize the use of language for communication purposes, and therefore emphasize the inclusion of multiple levels of language, including pragmatics (Bardovi-Harlig, 2007), and linguistic resources to construct meaning (Chapelle, 2009). On the other hand, other scholars highlight the significance of culture as an indispensable part of language (Byrnes, 2002; Kramsch, 1993). That is why pedagogies that foster the development of intercultural communicative competence (ICC) have gained importance. Language use is considered to be embedded in social activities in real life, which requires the development of translingual and transcultural competence (Byrnes, 2009). According to some authors, intercultural competence (ICC) is considered to be integrated into communicative competence (CC) (Balboni & Caon, 2014), and some others argue that CC could not exist without ICC (Lussier, 2009). That is, if the speaker uses the target language to communicate with native speakers in culturally homogenous context, that person needs CC. However, when the speaker uses the target language to communicate with foreigners who are non-native speakers, then the speaker needs both CC and ICC (Balboni & Caon, 2014). The latter focuses on establishing and maintaining social relationships rather than solely focusing on effective information exchange (Byram, 1997). While CC with its standardized native speaker norms considered target language-related cultural elements essential for effective communication, ICC focuses on international means of communication by accepting the lingua franca status of English (Alptekin, 2002). Language competence is now associated with both plurilingualism and interculturality, which expects language users to be able to expand their language skills from the target language's cultural context to diverse contexts of other speakers (Young & Sachdev, 2011). Alptekin (2002) argues that CC is strictly confined to the authenticity of native speaker language use and this approach ignores the interactions between non-native speakers of the target language.

Deardorff (2004) defines ICC as “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (p. 194). According to Byram (1997), effective communication in a foreign language is closely associated with other components such as skills, knowledge, and attitudes, all of which can be acquired or changed, and contribute to development of intercultural competence. Language users "understand how aspects of their own culture are perceived from the other’s cultural perspective and how this link between the two cultures is fundamental to interaction" (Chun, 2011, p. 393). ICC incorporates not only the understanding the culture of the target language, but also willingness to dispense with discredit and prejudice about the other cultures and reflect on one’s own culture.

Online intercultural exchange

Online communicative activities like OIE can be part of foreign language learning process (O’Dowd, 2007) as a mean of remote learning. These activities comprise structured tasks that aim at providing foreign language students with language skills and ICC. Language learners from different cultural/national backgrounds and distant geographical locations engage in working on a structured task (Guth & Helm, 2010). This way they have opportunities to put their knowledge of the target language into practice in a real-world context with real-life purposes without violating social distancing measures during emergency cases like pandemics. In OIE activities, numerous applications such as Skype, Facebook, Twitter, Google Hangouts, wikis, Facebook Live, Messenger or WhatsApp can be integrated in order to enhance intercultural communication (Guth & Marini-Maio, 2010; Jin & Erben, 2007; Lee & Markey, 2014).

The main aim of OIE is the development of linguistic and intercultural competencies. According to a study conducted by Vorobel and Kim (2012), OIE was found to be the second most frequent topic in studies focusing on remote foreign language teaching. OIE literature is growing with a number of studies (e.g., Flowers & Kelsen, 2016; O'Dowd, 2016; Wang et al., 2017). According to studies conducted in diverse cultural contexts, the common topics include contribution to foreign language learning, collaboration, interaction, 21st century skills, intercultural development and learner autonomy (Flowers et al., 2019; Luo & Gui, 2018; Wang et al., 2017). Among claimed benefits of such activities are sociolinguistic advances such as awareness of the social dimensions of language use like politeness and register, development of language skills such as spoken production, spoken interaction, written production, reading, listening, and codeswitching (Helm & Guth, 2010), development of ICC (Byram, 1997; Chun, 2011), language awareness and motivation (Michell, 2011), gaining fluency in speaking (Tian & Wang, 2010). These activities also give language learners chances to rehearse multiple literacy practices including media and academic literacy, critical thinking skills as well as collaborative skills (Belz, 2002; Helm & Guth, 2010; McCloskey, 2012; O’Dowd, 2003). A meta-synthesis of qualitative and quantitative findings of research on OIE revealed "a prevalence of positive telecollaborative experiences, as reported by the participants, resulting from a lively engagement with speakers of the target languages and people from diverse cultures" (Çiftçi & Savaş, 2018, p. 285). In order to shed light on the relevant literature on OIE and also on online foreign language teaching during emergency remote teaching, this study aimed to gather in-dept information about the learners’ opinions regarding their experience about how they engaged and performed a 6-week OIE activity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

The phenomenological research method, a qualitative research method, was used in this study because the subject to be discussed related to the experiences of the participants and phenomenology "makes sense of the experiences of individuals about a phenomenon" (Creswell, 1998, p. 51), "defining what and how the individual experiences" and "the essence of the individual's experiences" Patton (1990, p. 71). Phenomenological research aims to describe “core meanings in significant human experiences” (p. 71). It reveals “the interpretations of the experiences by the individuals” (Creswell, 1998, p. 51). Unlike experimental practices, phenomenology does not try to artificially reproduce the phenomenon under certain conditions. Cases are expected to occur spontaneously; no interference is made with the views, comments, perceptions and expressions of the participants during the interviews. The phenomenon is observed and reflected as it occurs and is experienced. Although we are in the same environments, our understanding of the phenomena around us differs from each other (Smith & Eatough, 2006). Although the phenomenon of teaching and learning is a phenomenon known by everyone, especially in the field of education, we all have a different approach and understanding. At this point, phenomenology tries to define the essence, its essential nature. In phenomenological research, there is no reason to defend or prove any theory. The phenomenological approach simply describes the phenomenon in as much detail as possible. This qualitative study aimed to explore firsthand experiences of EFL learners who participated in a five-week OIE activity. Since the aim of this study was concerned with gaining insight into the lived experiences of participants, phenomenological approach made it possible to get in-depth information regarding the experience of participants with their own words.

Participants

There were two stages in the study. In the first stage the OIE activity was conducted. In the second stage online interviews with voluntary participants were conducted. For the first stage, the researcher made an online invitation in two institutions one in China and the other in Turkey. The students who volunteered to participate were included in OIE activity upon receiving their confirmation through online consent forms. In total, 78 participants took part in the activity. 42 of the participants were studying Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics in China, and 36 of them were studying in Anadolu University in Turkey. For the second stage, the researcher made another invitation for the online interviews to those who took part in the OIE because in phenomenology research, data sources are the primary people who experience the phenomenon that the research focuses on and can reflect these experiences (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2005). Among those 78 participants, seven Chinese learners and six Turkish learners volunteered for the online interviews. Therefore the qualitative data was gathered from 13 participants in total.

An overview of the activity

The OIE activity lasted for six weeks. In the first phase of the activity two weeks were separated for getting used to the mobile application WeChat, pairing up, exchanging application IDs, getting to know each other and introducing OIE activity. The mobile application WeChat, was used in this study as it is widely used in China and it supports different communication modes like text messages, photos, video or text files, voice recordings, and videoconferencing. In the second phase of the activity the learners exchanged information about celebrations and festivals in their cultures for three weeks. During this exchange they were free to choose any mode of communication mentioned earlier. They were expected to define the celebration, describe how it takes take place and what cultural aspects are associated with the celebration. The end product of the activity was shooting a video. This took place in the final phase, and it lasted a week. The participants were expected to make a video in which they selected one of the celebrations in each other's culture and narrated it. While preparing their videos the participants asked questions to each other in order to get details about the celebrations. They were supposed to negotiate while making comparisons about celebrations in each other's cultures. They were expected to present their videos during an online videoconferencing session with the participation of other students in the study.

Data collection

In phenomenological research, when collecting data from individuals who have experienced the event firsthand, many methods such as observation, diary, art product, reflection report, all kinds of artistic content in which the experiences are reflected can be adopted, but the most commonly used method is in-depth interview or multiple interviews (Çekmez et al., 2012). During the interviews, a single question to reveal the subjective experiences of the individuals can be asked, or detailed information can be collected by asking more than one question according to the purpose of the research. The most common questions are as follows: 1. What did you experience? 2. What conditions and situations affected your experience? In this study, following the OIE activity, one-to-one online interviews were conducted with 13 participants on Zoom, a videoconferencing platform. The interviews included one leading open-ended question and additional follow up questions based on the responses of the participants. The main question asked to the participants was "How did you find the OIE activity?". The interviews lasted 25-30 minutes. The follow up questions such as "In what ways?", "Can you give examples?", "What made you think so?", "Can you be more specific?", "Can you give more details?" aimed to gather in-depth information on the participants’ perceptions about OIE activity in relation to development of EFL learning skills and ICC. Even though there were pre-planned questions, the interviews were conversational with questions flowing according to preceding answers when possible.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to serve the purpose of this study. Thematic analysis is considered to be compatible with qualitative descriptive approaches such as descriptive phenomenology (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). For some researchers, thematic analysis is considered as an inherent part of phenomenology (Holloway, 2005). Thematic analysis is described as “a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79). According to Sparkes (2005), thematic analysis is used in order to examine the narrations of real life stories analytically by breaking the texts into smaller units such as codes. In this study, after the interviews were transcribed, the content was analyzed inductively, which is a technique where the codes are derived directly from the text data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). As the first step, the statements that identify the phenomenon were highlighted. The statements were grouped to create codes that were independent from each other. After all codes were created, they were combined into more general themes that describe the phenomenon. Two independent researchers read and analyzed the same set of transcripts, and then compared their codes. Negotiations were carried out until all the codes agreed to make them credible.

Results

The themes revealed by the thematic analysis were grouped under three categories: (1) Perceptions regarding the OIE activity, (2) Contribution of OIE activity to EFL learning process, and (3) Contribution of OIE activity to development of ICC. This section reports these three categories respectively. The findings are presented according to this outline: The first category, which is perceptions regarding the OIE activity, is followed by the codes and themes table and finishes with the direct quotes of the participants. Likewise, the second and third categories are followed by the codes and themes table and finish with the direct quotes of the participants.

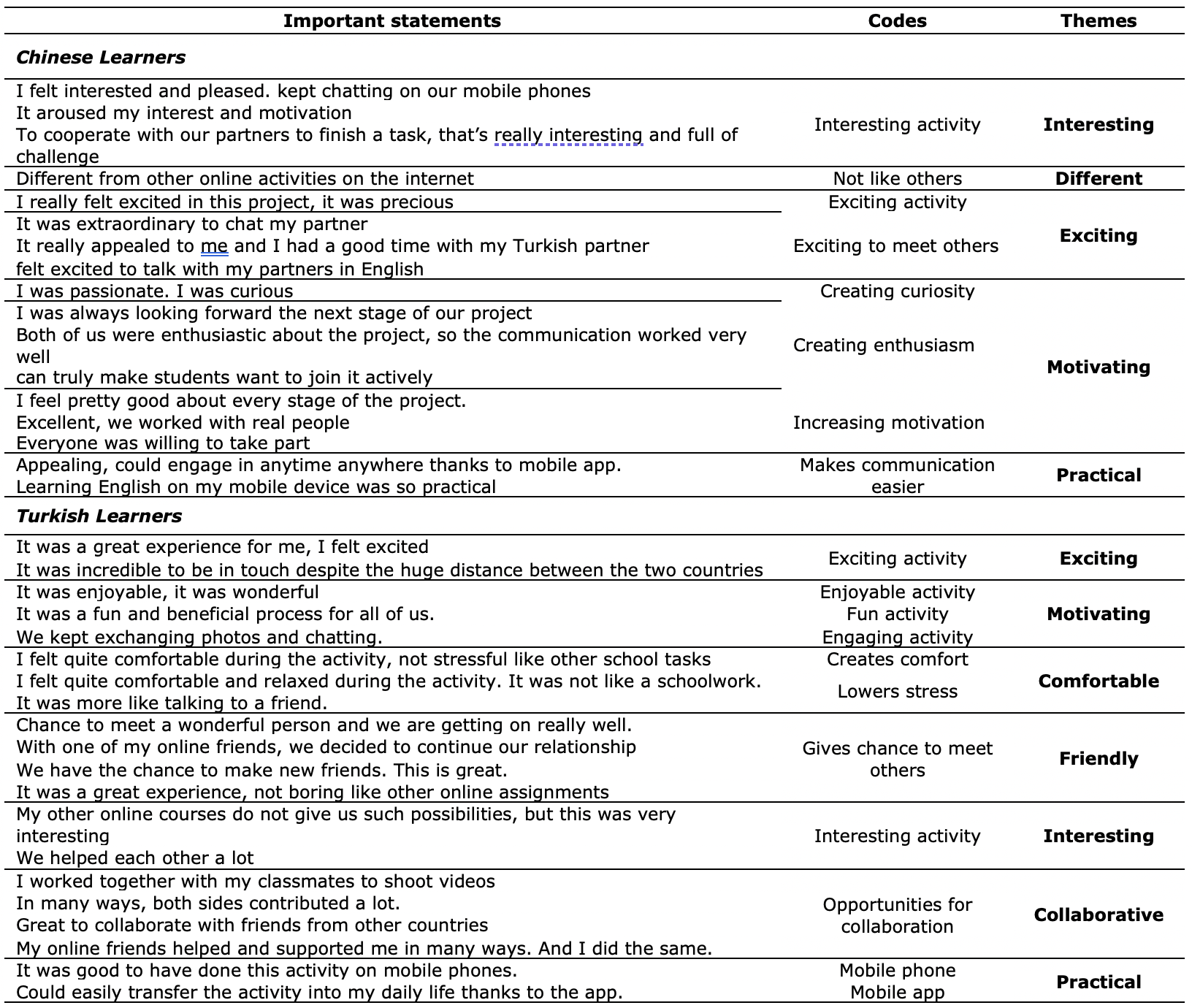

As for the first category, thematic analysis revealed that majority of the participants from both countries were satisfied with the OIE activity. Most of the participants found the activity interesting, exciting and appealing. Table 1 shows important statements, codes and themes emerged from the analysis of Chinese and Turkish learners’ responses respectively regarding their perceptions about the activity.

Table 1: Perceptions regarding the OIE activity

According to the findings on perceptions in both groups, learners described the activity as motivating, interesting and practical, and they believed that OIE created opportunities for language practice, building new friendships, and collaboration. Responses revealed that they valued the activity more than other courses as the activity was interesting and authentic, not like other boring online assignments. Some of their statements were as follows:

It really appealed to me and I had a good time with my Turkish partner. I felt comfortable to talk with my partners in English.

Both of us were enthusiastic about the project, so the communication worked very well.

I was passionate. I was curious. My other online courses do not give us such possibilities. This activity was a great experience.

I felt quite comfortable and relaxed during the activity. It was not like a schoolwork. It was more like talking to a friend.

Different from other online activities on the internet. To cooperate with our partners to finish a task, that’s really interesting and full of challenge.

Meeting a new friend, getting to know the person better, becoming sincere and close and having a journey into his/her life were incredibly different experiences for me.

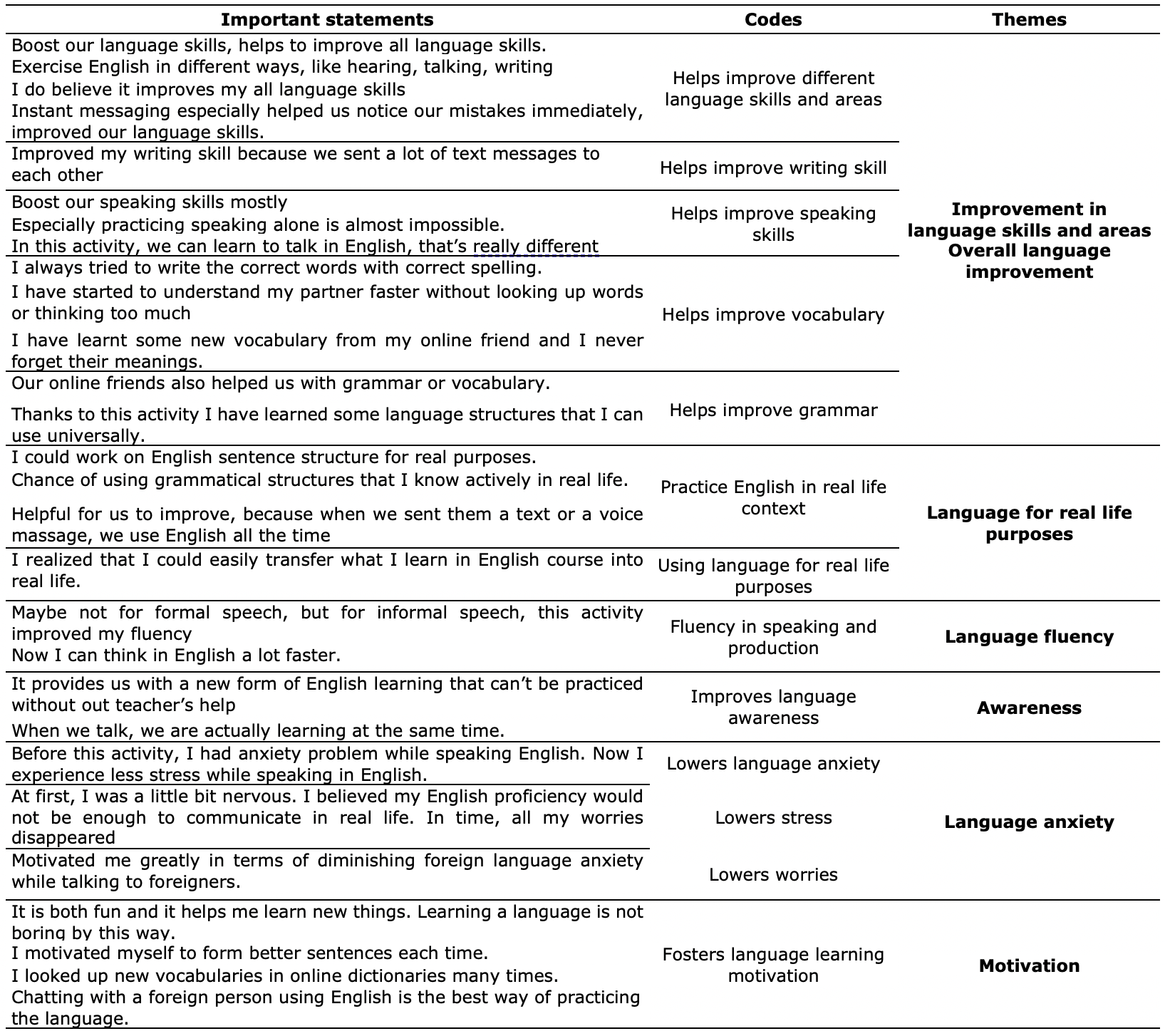

For the second category, which focuses on the contribution of OIE activity to EFL learning process, both Chinese learners and Turkish students believed that the activity greatly contributed to the language learning process by communicating with real people for real purposes. Different communication modes such as voicemail, text message, videos seemed to have enhanced development of different language learning. Table 2 shows important statements, codes and themes emerged from the analysis of Chinese and Turkish learners’ responses regarding EFL learning process.

Table 2: Contribution of OIE activity to EFL learning process

Participants highlighted that the activity contributed to the development of all foreign language skills as a whole. They emphasized that thanks to this activity, they became aware of their foreign language competence, their foreign language anxiety disappeared, and they were more motivated and fluent because they used the language in real life for real purposes. Some of their statements are as follows:

This activity extremely helped me improve my language skills and also my communication skills in a foreign language.

We have a chance to use our language skills actively like in real life.

I checked if my expression is correct before I text them, we corrected our mistakes together. I could improve my speaking skill, vocabulary, and grammar knowledge. I improved my writing fluency. I have started writing faster.

Before this activity, I had anxiety problem while speaking English. Now I experience less stress while speaking in English.

It motivated me greatly in terms of diminishing foreign language anxiety while talking to foreigners. I realized that I can express myself in a foreign language as I do in my mother tongue.

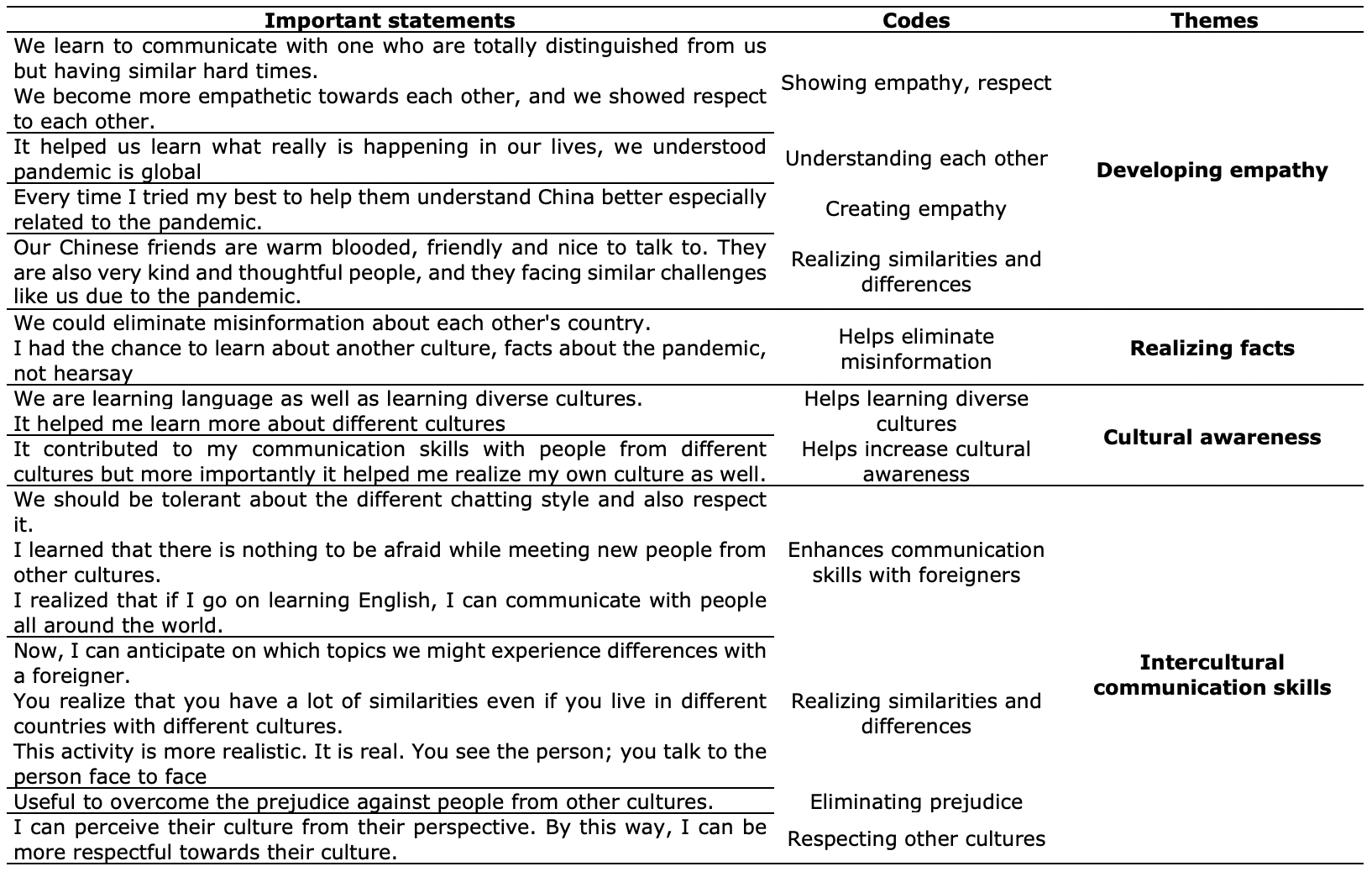

As for the final category, which focuses on contribution of OIE to development of ICC, the participants emphasized that the OIE activity made them realize that being in completely different cultures and being geographically distant does not hinder communication. They also stated that they learned to show empathy to each other in a difficult process such as the pandemic, and they were able to eliminate misinformation about each other's country caused by social media. Most importantly, they stated that although they looked very different, they actually had very similar daily lives, responsibilities, interests, and challenges. Table 3 shows important statements, codes and themes emerged from the analysis of Chinese and Turkish learners’ responses regarding development of ICC.

Table 3: Contribution of OIE Activity to Development of ICC

As the participants emphasized, getting to know people from different cultures helped them realize how much they had in common despite their differences. In addition, thanks to this activity, the participants realized that they need to show more tolerance, respect, and empathy while communicating with individuals from different cultures. Emphasizing that using English as a foreign language in intercultural communication had a very satisfactory result, the participants stated that a foreign language is an excellent tool for communicating with anyone from a different country. The participants stated that their anxiety about using foreign languages decreased thanks to this activity and their confidence in their foreign language competencies increased. Some of the statements of the participants are as follows:

I understood very well that one foreign language is perfectly enough to combine two different cultures.

I had the chance to learn about another culture, facts about the pandemic, not hearsay,

I realized that there was nothing to hesitate while communicating with people from other cultures. We are having similar hard times,

Cultural differences drew my attention a lot. There were a lot of differences and similarities in terms of eating habits, dressing and of course the changes in our lives due to the pandemic,

I realized that if I go on learning English, I can communicate with people all around the world.

I believe that, the next time I meet a foreign person from another country, I can express my opinions without having difficulty or stress.

At first, I was scared about sharing something and talking but in time it got easier. As university students in different countries, we shared a lot in common, especially during hard days of the pandemic,

Each time I noticed a cultural difference I became more empathetic towards different cultures and I learned to appreciate the differences.

Discussion

Overall, the aim of the study was to create an authentic language learning environment that supported development of foreign language learning skills through the implementation of an OIE activity and ICC during emergency remote teaching. The study was aligned with the sociocultural view of language learning that requires promotion of interaction and collaboration (Guth & Helm, 2011) in social context. The findings are discussed below in terms of participants' perceptions, contribution to foreign language learning process and ICC respectively.

Perceptions regarding OIE

In general, the findings revealed a general satisfaction among the participants regarding the OIE, which is a similar finding with relevant literature including similar responses such as fun, exciting, interesting, rewarding, beneficial (see Belz, 2006; Chen & Yang, 2014; Helm & Guth, 2010; Tian & Wang, 2010). Participants in both groups shared similar attitudes and perceptions towards the activity as they all found the activity exciting, interesting, and motivating. Turkish Participants also claimed that the activity was enjoyable; it helped them build friendships and encouraged them to collaborate.

Foreign language learning process

Regarding the linguistic benefits of the OIE, the responses indicated that the activity promoted their foreign language learning process in many ways. The responses showed that for both groups the activity triggered language awareness, learner autonomy, motivation, and willingness to practice the language in real life. Learner motivation, willingness to communicate, and learner autonomy are considered significant attitudinal components in the realm of language learning (Benson, 2007; Dörnyei, 1998; Gardner & Lambert, 1972; MacIntyre et al., 1998). According to some researchers, synchronous communication motivates participants and encourages participation and interaction. As a result, it enhances language acquisition (Jauregi & Bañados, 2008; Lee, 2006; Sotillo, 2000). In OIE activities, like the one adopted in this study, the participants collaborate to create an end product, which was shooting a video about a celebration in each other's culture, and this enhanced engagement and participation as tasks that require design, production, and sharing are embraced by the learners leading to increased participation (Satar & Akcan, 2018). Activities like OIE contribute to interaction and communication by engaging learners in exchanging information feedback with each other, which in return enhance better performance, reinforce communicative purpose and sociocultural competence (Pegrum, 2014).

In terms of OIE's contribution to language skills and areas, some participants pointed out that OIE activity helped them improve their grammar and vocabulary knowledge, partly thanks to feedback they got from each other as in Lee’s (2002) study. The participants in this study stated that they had to search for new words and look up the vocabulary in their partner's responses in order to maintain their conversations. Their responses revealed that they appreciated this process as it helped them improve their English vocabulary. Similarly, language learning gains are highlighted in OIE literature. Thanks to negotiations of meaning due to semantic misunderstandings in exchanges (O’Rourke, 2005) and searching for new vocabulary to maintain the conversations. OIE activities help learners enrich their inventory of vocabulary and also develop their writing and feedback giving skills (Guth & Marini-Maio, 2010). The participants in this study frequently emphasized the contribution of the activity to their speaking skills and stated that it helped them gain fluency through practice in authentic context. This finding is also supported in the relevant literature. The results in similar studies revealed the same perceptions as participants claimed that OIE helped them gain confidence in speaking, increased their comprehension of spoken language, appreciated getting feedback from their partners for pronunciation and found the activity rewarding for practicing speaking (see Polisca, 2011; Tian & Wang, 2010). Participants pointed out that they searched for new words to make sentences and they engaged in grammar self-check before conveying their messages.

As for the affective side, OIE seems to be appreciated by the participants of this study. As in findings of other studies in OIE research (Angelova & Zhao, 2016; Belz, 2006; Lee & Markey, 2014; Ware & O’Dowd, 2008), in this study, OIE seemed to contribute to higher motivation and helped lower foreign language anxiety. Both groups were aware of the fact that they were all EFL learners, not native spea

kers. Participants mentioned that they did not feel anxious about their language mistakes while interacting with their peers. Actually, the responses emphasized how comfortable the participants felt about being foreign language learners during language exchanges. Similarly, in the study of Bueno-Alastuey and Kleban (2016) Polish and Spanish participants used English as a lingua franca and stated positive opinions regarding activity’s contribution to their communicative competence. In Jenkins' (2009) study participants stated that using English as a lingua franca to practice with other non-natives was an added opportunity for them. As Alptekin (2002) states “with authenticity being dependent on the authority of the native speaker, the notion of learner autonomy suffers dramatically” (p. 61), using English as a lingua franca might decrease foreign language anxiety and help learners gain autonomy in less stressful learning atmosphere.

Intercultural communicative competence

Byram (1997) mentions attitude as a pre-requisite for ICC by defining it as “curiosity and openness, readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and beliefs about one’s own” (p. 50). In this study, both Chinese and Turkish students showed curiosity and willingness to learn about each other’s culture. They mentioned how interesting it was to learn more about the other culture and how they felt each time they learned similarities between the two cultures. The emerging themes for both groups were cultural awareness, development of intercultural communication skills, collaboration, friendship, and understanding cultural diversity and becoming empathetic towards others. These themes might indicate that OIE contributes to the development of ICC, as supported in a body of research in the literature (Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, 2016; O’Dowd, 2007). According to Harden (2000), ICC is not attainable through any kind of formal teaching, and the only way to develop it is to practice through first-hand experience in real life context. The participants of this study frequently stated that they had a chance to learn about the other culture, enhance their communication skills with foreigners, realize similarities and differences through practice in real life context, whereby gained experience and confidence in communication across cultures. The participants in both groups admitted that they became more aware of their similarities and differences, which helped them become more tolerant and understanding towards people in other cultures. They accepted that the activity helped them eliminate misinformation about each other's country especially related to pandemic. They emphasized that this activity was very beneficial for them to be more empathetic and tolerant by eliminating prejudices against each other. According to the responses of the participants, the activity seemed to raise awareness of how the global pandemic is creating similar challenges in people's lives. Some participants mentioned about the delays in responses due to other responsibilities such as other online assignments and work, as some learners who experienced financial loses or whose parents lost their jobs inTurkey had to start working part-time during the pandemic. According to the relevant literature, among the most common gains of OIE activities is the development of ICC (Bray & Iswanti, 2013), and among the most common challenges is delayed responses during asynchronous exchanges (Nicolaou & Sevilla-Pavón, 2016). The participants in this study had a chance to show empathy towards each other, which is a finding related to ICC. The unusual conditions of the global pandemic might be one of the reasons of delayed responses. Therefore, as this study took part during the global pandemic, this finding might be considered as a unique contribution to OIE literature. The participants also highlighted that the differences between the two cultures are disappearing as they are experiencing the same challenges and dramatic changes in their lives.

The findings of this study might contribute to emergency remote foreign language teaching literature. In general, responses revealed that the OIE activity in this study has potential to make language learning enjoyable, interesting, motivating, and meaningful with chances to practice the target language in real-life context for real purposes without time and place constraints. Therefore, such online exchanges can be regarded as effective alternatives for remote language learning practices. It can also be concluded that OIE activity has potentials to create cultural and intercultural awareness in more authentic process. Self-efficacy is supported by means of highly motivating engagements and peer collaboration. Foreign language skills, language learning strategies as well as spoken and written fluency have been developed through meaningful language exchanges. OIE also contributes to development of learner autonomy, which in return enhances life-long learning.

The global pandemic transferred educational practices into emergency remote teaching practices and alternative pedagogies which are both feasible and practical and should be implemented to make language learning processes more effective. Language learners should be able to take advantage of the engaging activities provided by their teachers who can use a task participation framework to support the design and presentation of tasks (Egbert, 2020). During the pandemic, foreign language learning faces external factors that affect the quality of life due to the necessity of social distance, loneliness, and low individual control. These factors are likely to increase negative perception of the online learning environment especially when there is lack of social interaction (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021). An OIE activity might be a practical solution to eliminate such factors as it combines sociocultural dimension of learning with interaction. It may help learners scaffold each other’s learning by providing cultural meanings. In this way, learners guide each other for discovery and meaning making through co-construction processes (Golonka et al., 2017). The findings of this research show that online learning creates environments for learners to get involved in social learning, collaboration, and active participation, and it offers digital learning spaces (Masterson, 2020). Especially mobile devices seem to best fit for the learner characteristics of the target age group used in this study.

References

Ahmad, C. N. C., Shaharim, S. A., & Abdullah, M. F. N. L. (2017). Teacher-student interactions, learning commitment, learning environment and their relationship with student learning comfort. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 14(1), 57-72. https://www.tused.org/index.php/tused/article/view/137/93

Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.1.57

Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 4(2), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v4i2.149

Angelova, M., & Zhao, Y. (2016). Using an online collaborative project between American and Chinese students to develop ESL teaching skills, cross-cultural awareness and language skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(1), 167-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.907320

Aquino, E. M. L., Silveira, I. H., Pescarini, J. M., Aquino, R., Souza-Filho, J. A. S, Rocha, A. d. S., Ferreira, A., Victor, A. Teixeira, C., Machado, D. B., Paixão, E., Alves, F. J. O., Pilecco, F., Menezes, G., Gabrielli, L., Leite, L., de Almeida, M. C. C., Ortelan, N., Fernandes, Q. H. R. F., & Ortiz R. J. F. (2020). Social distancing measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic: potential impacts and challenges in Brazil. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 25, 2423-2446. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.1.10502020

Balboni, P. E., & Caon, F. (2014). A performance-oriented model of intercultural communicative competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 35, 1-12. https://immi.se/oldwebsite/nr35/balboni.html

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2007). One functional approach to second language acquisition: The concept-oriented approach. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 57-76). Routledge.

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Belz, J. A. (2002). Social dimensions of telecollaborative foreign language study. Language Learning & Technology, 6(1), 60-81. http://dx.doi.org/10125/25143

Belz, J. A. (2006). At the intersection of telecollaboration, learner corpus analysis, and L2 pragmatics: Considerations for language program direction. In J. A. Belz & S. L. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education (pp. 207–246). Heinle & Heinle.

Benson, P. (2007) Autonomy in language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bray, E., & Iswanti, S. N. (2013). Japan–Indonesia intercultural exchange in a Facebook Group. The Language Teacher, 37(2), 29–34.https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTTLT36.2-5

Bueno-Alastuey, M. C., & Kleban, M. (2016). Matching linguistic and pedagogical objectives in a telecollaboration project: A case study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(1), 148-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.904360

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

Byrnes, H. (2002). The cultural turn in foreign language departments: Challenge and opportunity. Profession, 114-129.https://www.jstor.org/stable/25595736

Byrnes, H. (2009). Revisiting the role of culture in the foreign language curriculum. The Modern Language Journal, 94(2), 315-336.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01023.x

Chapelle, C. A. (2009). The relationship between second language acquisition theory and computer-assisted language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 93(1), 741-753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00970.x

Chen, J. J., & Yang, S. C. (2014). Fostering foreign language learning through technology-enhanced intercultural projects. Language Learning & Technology, 18(1), 57-75. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44354

Chun, D. M. (2011). Developing intercultural communicative competence through online exchanges. CALICO Journal, 28(2), 392.https://www.jstor.org/stable/calicojournal.28.2.392

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative research and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage.

Çekmez, E., Yıldız, C., & Bütüner, S. Ö. (2012). Phenomenographic research method. Necatibey Eğitim Fakültesi Elektronik Fen ve Matematik Eğitimi Dergisi, 6(2),77-102. http://www.nef.balikesir.edu.tr/~dergi/makaleler/yayinda/13/EFMED_FBE180.pdf

Çiftçi, E. Y., & Savaş, P. (2018). The role of telecollaboration in language and intercultural learning: A synthesis of studies published between 2010 and 2015. ReCALL, 30(3), 278-298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000313

Dearden, J. (2015). English as a medium of instruction —A growing global phenomenon. British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/e484_emi_ cover_option_3_final_web.pdf

Dearden, J. (2018). The changing roles of EMI academics and English language specialists. In Y. Kirkgöz & K. Dikilitas (Eds.), Key issues in English for specific purposes in higher education (pp. 323-338). Springer.

Deardorff, D. K. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. North Carolina State University.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language teaching, 31(3), 117-135.https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

Egbert, J. (2020). The new normal?: A pandemic of task engagement in language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 314-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12452

Ellis, R. (2000). Learning a second language through interaction. John Benjamins.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Feng, R., Shi, X., Hu, S., & Yu, Y. (2021). Feedback and uptake in videoconferences for online intercultural exchange. Journal of Virtual Exchange, 4, 28-46. https://doi.org/10.21827/jve.4.37159

Flowers, S. D. & Kelsen, B. A. (2016) Digital sojourn: Empowering learners through English as a lingua franca. In P. Clements, A. Krause, A., & H. Brown (Eds.), Focus on the learner. JALT.

Flowers, S., Kelsen, B., & Cvitkovic, B. (2019). Learner autonomy versus guided reflection: How different methodologies affect intercultural development in online intercultural exchange. ReCALL, 31(3), 221-237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344019000016

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Newbury House.

Golonka, E. M., Tare, M., & Bonilla, C. (2017). Peer interaction in text chat: Qualitative analysis of chat transcripts. Language Learning & Technology, 21(2), 157–178. https://dx.doi.org/10125/44616

Guth, S., & Helm, F. (2011). Developing multiliteracies in ELT through telecollaboration. ELT Journal, 66(1), 42-51.https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr027

Guth, S., & Marini-Maio, N. (2010). Close encounters of a new kind: The use of Skype and Wiki in telecollaboration. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0 (pp. 413–427). Peter Lang.

Harden, T. (2000) The limits of understanding. In T. Harden & A. Witte (Eds.), The notion of intercultural understanding in the context of German as a foreign language (pp. 103-123). Peter Lang

Helm F., & Guth, S. (2010). The multifarious goals of telecollaboration 2.0: Theoretical and practical implications. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0 (pp. 69–106). Peter Lang.

Holloway, I. (2005). Qualitative research in health care [e-book]. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jauregi, K., & Bañados, E. (2008). Virtual interaction through video-web communication: A step towards enriching and internationalizing learning programs. ReCALL, 20(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344008000529

Jenkins, J. (2009). Exploring attitudes toward English as a lingua franca in the East Asia context. In K. Murata & J. Jenkins (Eds.), Global Englishes in Asian contexts: Current and future debates (pp. 40-56). Springer.

Jin, L., & Erben, T. (2007). Intercultural learning via instant messenger interaction. CALICO Journal, 24(2), 291-311.https://www.jstor.org/stable/24147913

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Addison-Wesley Longman.

Lee, L. (2002). Enhancing learners' communication skills through synchronous electronic interaction and task-based instruction. Foreign Language Annals, 35(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2002.tb01829.x

Lee, L. (2006). A study of native and nonnative speakers' feedback and responses in Spanish-American networked collaborative interaction. In J. A. Belz, & S. L. Thorne (Eds.) Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education, (pp. 147–76). Heinle.

Lee, L., & Markey, A. (2014). A study of learners’ perceptions of online intercultural exchange through Web 2.0 technologies. ReCALL, 26(3), 281-297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344014000111

Loewen, S., & Sato, M. (2018). Interaction and instructed second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 51(3), 285-329.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000125

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), The new handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). Academic Press.

Luo, H. & Gui, M. (2018) Review of online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice. Language Learning & Technology, 22(1), 56–59. https://dx.doi.org/10125/44578

Lussier, D. (2009). Common reference framework for the teaching and assessment of ‘Intercultural Communicative Competence’. In Studies in Language Teaching, ALTE 2008 (pp. 234-244). Cambridge University Press.

MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x

Maican, M.-A., & Cocoradă, E. (2021). Online foreign language learning in higher education and its correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(2), 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020781

Masterson, M. (2020). An exploration of the potential role of digital technologies for promoting learning in foreign language classrooms: Lessons for a pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(14), 83-96.https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i14.13297

McCloskey, E. M. (2012). Global teachers: A conceptual model for building teachers’ intercultural competence online. Comunicar, 38, 41–49.

Michell, H. (2011). A critical analysis of the effects of a videoconferencing project on pupils’ learning about culture and language. Journal of Trainee Teacher Education Research, 2, 51-88. http://jotter.educ.cam.ac.uk/volume2/051-088-michellh/051088-michellh.pdf

Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–6.https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

Nicolaou, A., & Sevilla-Pavón, A. (2016). Exploring telecollaboration through the lens of university students: A Spanish-Cypriot telecollaborative exchange. In S. Jager, M. Kurek, & B. O’Rourke (Eds.), New directions in telecollaborative research and practice: selected papers from the second conference on telecollaboration in higher education (pp. 113–119). Research-publishing.net

O’Dowd, R. (2003). Understanding the ‘other side’: Intercultural learning in a Spanish-English email exchange. Language Learning and Technology, 7(2), 118–144. http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num2/odowd

O’Dowd, R. (Ed.) (2007) Online intercultural exchange: An introduction for foreign language teachers. Multilingual Matters.

O’Dowd, R. (2016) Emerging trends and new directions in telecollaborative learning. CALICO Journal, 33(3): 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v33i3.30747

O’Dowd, R., & Lewis, T. (2016). (Eds). Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice. Routledge

O’Dowd, R., & Ritter, M. (2006). Understanding and working with ’failed communication’ in telecollaborative exchanges. CALICO Journal, 23(3), 623-642. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24156364

O’Rourke, B. (2005). Form-focused interaction in online tandem learning. CALICO, 22(3), 433–466.https://www.jstor.org/stable/24147933

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage.

Pegrum, M. (2014). Mobile learning: Languages, literacies and cultures. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pica, T. (1998). Second language learning through interaction: Multiple perspectives. In V. Regan (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to second language acquisition in context (pp. 1-31). University of Dublin Press.

Pica, T. (2013). From input, output and comprehension to negotiation, evidence, and attention: An overview of theory and research on learner interaction and SLA. In M. del P. García Mayo, M. J. Gutierrez Mangado & M. Martínez-Adrian (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to second language acquisition. (pp. 49-69). John Benjamins.

Polisca, P. (2011). Language learning and the raising of cultural awareness through Internet telephony: A case study. The Language Learning Journal, 39(3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2010.538072

Porto, M., Golubeva, I., & Byram, M. (2021). Channelling discomfort through the arts: A Covid19 case study through an intercultural telecollaboration project. In M. Porto & S. A. Houghton (Eds.), Arts integration and community engagement for intercultural dialogue through language education. Special topic issue of language teaching research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211058245

Satar, H. M., & Akcan, S. (2018). Pre-service EFL teachers’ online participation, interaction, and social presence. Language Learning & Technology, 22(1), 157-183. https://dx.doi.org/10125/44586

Schwienhorst, K. (2008). CALL and autonomy: Settings and contexts variables in technology-enhanced language environments. Independence, 43, 13-15.

Sepulveda-Escobar, P., & Morrison, A. (2020). Online teaching placement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 587-607. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1820981

Seidlhofer, B. (2013). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford University Press.

Saito, K., & Akiyama, Y. (2017). Video-based interaction, negotiation for comprehensibility, and second language speech learning: A longitudinal study. Language Learning, 67(1), 43-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12184

Smith, J. A. & Eatough, V. (2006) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In G. M. Breakwell, S. Hammond, C. Fife-Schaw, & J. A. Smith (Eds.). Research methods in psychology (3rd ed.) (pp. 182-209). Sage.

Sotillo, S. M. (2000) Discourse functions and syntactic complexity in synchronous and asynchronous communication. Language Learning and Technology, 4(1), 82–119. http://dx.doi.org/10125/25088

Sparkes A. (2005). Narrative analysis: Exploring the whats and hows of personal stories. In I. Holloway (Ed.). Qualitative research in health care. Open University.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. M. Gass & C. G. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235–253). Newbury House.

Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principle and practice in applied linguistics: Studies in honour of H. G. Widdowson (pp.125-144). Oxford University Press.

Tian, J., & Wang, Y. (2010). Taking language learning outside the classroom: Learners' perspectives of eTandem learning via Skype. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 4(3), 181-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2010.513443

Tudini, V. (2012). Online second language acquisition. Continuum.

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Vorobel, O., & Kim, D. (2012). Language teaching at a distance: An overview of research. Calico Journal, 29(3), 548.https://www.jstor.org/stable/calicojournal.29.3.548

Ware, P. D., & O’Dowd, R. (2008). Peer feedback on language form in telecollaboration. Language Learning & Technology, 12(1), 43-63. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44130

Wang, R., Rechl, F., Bigontina, S., Fang, D., Günthner, W. A. & Fottner, J. (2017, July, 20-22) Enhancing intercultural competence of engineering students via GVT (global virtual teams)-based virtual exchanges: An international collaborative course in intralogistics education. [Conference Session]. International Conference e-Learning 2017. Lisbon, Portugal. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED579381.pdf

Watson-Gegeo, K. A., & Nielsen, S. (2003). Language socialization in SLA. In C. J. Doughty & S. Nielsen (Eds). The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 155-171). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756492.ch7

World Bank Education Global Practice (2020) Guidance note: remote learning & COVID-19. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/531681585957264427/GuidanceNote-on-Remote-Learning-and-COVID-19

Wright, R., Jones, G., & D’Alba, A. (2015). Online students’ attitudes towards rapport-building traits and practices. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 17(1), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIL.2015.066063

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Yıldırım, A., & Şimsek, H. (2005). Nitel araştırma teknikleri [Qualitative research techniques]. Seçkin

Young, T. J., & Sachdev, I. (2011). Intercultural communicative competence: Exploring English language teachers’ beliefs and practices.Language Awareness, 20(2), 81-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2010.540328