Introduction

English teaching in public secondary schools in Mexico started in 1926 when it was established as mandatory in the educational system (Acuerdo número 20/12/16, 2016). Throughout the years, there have been educational reforms that have stated the approach to be followed in English teaching in secondary school. Examples of those reforms are those of 1993, 2006, and 2009 (published in 2011). The English program derived from this latter was Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (PNIEB) (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011a), its corresponding English version was National English Program in Basic Education (NEPBE).

In 2016, there was a modification to the national program (Plan de estudios 2011) to be compatible with a society that has become more educated, plural, democratic, and inclusive (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2016). This resulted in the 2016 Educational Model (Modelo Educativo 2016), whose new study plan was the Key Learning for Integral Education (Aprendizajes Clave para la Educación Integral). The English program presented in this new document had some modifications with respect to NEPBE; two of them were the redefinition of the general and specific purposes so that it could be aligned to international standards, and the inclusion of didactic orientations offering strategies to achieve the goals (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2017). However, some core elements remained, such as the social practice of the language, the action pedagogic approach, the environments, the language product methodology, and the contents related to language skills and activities established as achievements in the NEPBE.

In order to deal with the transition, at the moment of this study, secondary English teachers adopted the new model gradually. Usually, the NEBPE continued to be used in third grade and sometimes in second grade, and the 2016 Model was implemented in first grade and sometimes in second grade since it was not established that the three grades should work with it.

Considering the context of English teaching, it is paramount to investigate the practices teachers used to cope with simultaneous English programs. However, little research has been carried out on how English is taught in secondary schools in Mexico (Ramírez-Romero, 2009), including the public sector. The problem related to the deficiencies that students have in English as a subject in public schools is not recent, as Davies (2007) explains in his article, in which he concludes by stating that the English programs in Mexico have had poor results in the past 50 years.

It is, hence, the purpose of this paper to present how writing is taught in five public secondary schools in a city in Sonora, a northwestern state in Mexico.

Theoretical Framework

What does writing mean in today’s global context?

The way people write nowadays has changed. People write in online chats, texting, and social media. It could even be affirmed that today’s society writes more than ever before. This has implications for teachers as to what kind of writing they should teach their students that adhere to their actual and current needs and interests.

Regarding the type of writing to be taught to students, Ur (2012) presents two broad categories that she calls styles: formal and informal writing. The author explains that formal writing includes texts that follow standard rules and forms that are usually edited and addressed to an audience whose immediate response is not expected. Examples of such texts are newspaper articles, webpages, books, etc. Informal writing, on the other hand, included texts that are addressed to a specific audience or individual from whom rapid response might be expected; also, these texts tend to ignore standard rules and forms. Instant messaging and notes are examples of this writing style.

On their part, Brown and Abeywickrama (2018) present three writing genres, namely, academic writing (essays, short-answer test responses, theses, etc.), job-related writing (messages, emails, letters, manuals, etc.), and personal writing (messages, notes, invitations, diaries, etc.). The authors do not define these categories; however, the examples they give for academic and job-related writing seem to fit into what Ur (2012) defines as formal writing, while personal writing can be categorized as informal writing. Similarly, McDonough et al. (2013) present six types of writing: personal writing (diaries, journals, shopping lists, etc.), public writing (form filling, complaint letters, etc.), creative writing (poems, novels, songs, etc.), social writing (letters, notes, invitations, emails, etc.), study writing (making and taking notes, summaries, reviews, essays, etc.), and institutional writing (agendas, minutes, reports, instructions, etc.). From the examples provided by the authors, public and institutional writing may fall into formal writing, while personal writing can be considered informal. As for the rest of the types of writing, some overlapping is visualized. For example, creative writing can be either formal or informal; this will depend on the writer’s intention and audience. Similarly, study writing can be formal if it is a task for submission, but it can be informal if it takes the form of a student’s personal notes. Finally, social writing can be either formal or informal depending on the intended audience.

Considering this, teachers should then analyze their students’ writing needs and interests before choosing any writing style or genre, so that writing serves as a genuine means for communicating with a real purpose. In fact, Scrivener (2011) recommends carrying out a needs analysis to design writing tasks that are relevant to students. The following sections offer background information on what English teachers should know when teaching writing.

What does writing in English as a second/foreign language mean?

As stated by Brown (2002), having a simple view of writing leads to considering it as spoken language put into written words. However, this skill is complex since the same author affirms that “Written products are often the result of thinking, drafting and revising procedures that require specialized skills, skills that not every speaker develops naturally” (p. 335). In fact, Raimes (1983) emphasizes that one of the differences between speaking and writing is that the latter requires systematic teaching. Similarly, Harmer (2007) presents the writing process as a time-consuming activity that is not developed in a simple way. Finally, Hayik (2018) describes the process of teaching writing in an English as a Second or Foreign Language (ESL/EFL) context as challenging.

In the ESL/EFL classroom, the fact that students are taught how to speak does not mean that they will be able to write, for writing is not just putting discourse down on paper (Raimes, 1983); therefore, writing needs to be taught. In addition, nowadays there are new ways of communicating in written form which do not necessarily require long, complex compositions or even letters. Regardless of this, writing remains an important skill to be developed in our students, especially if they are to perform in academic and professional contexts.

In agreement with the complexity around the writing skill, NEPBE and 2016 Model state that communicating successfully in oral or in written form is a complex process that entails using the language (knowledge, abilities, and attitudes) with different purposes in different social contexts (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b; 2017). Besides, NEPBE uses the definition of writing by Pérez and Zayas (2007), who state that “writing is not copying or having good handwriting; writing is creating a text” (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b, p. 101). Similarly, Nation (2009) presents a meaning-driven principle which, in summary, emphasizes meaning considering the genre. In other words and following the author, students should write to communicate meaning in accordance with the type of text they write; moreover, he adds complexity to this recommending that learners “bring experience and knowledge to their writing” (p. 93), and he also recommends that learners be prepared for this activity through the choice of topic or previous work on the topic.

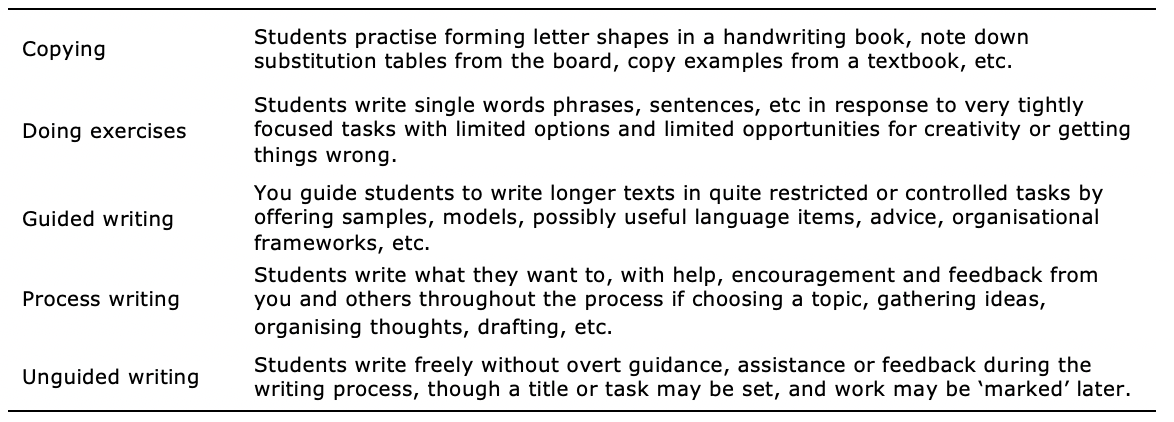

English teachers may ask what a writing activity is considering the complexity offered by Brown (2002), Harmer (2007) and Hayik (2018). In real contexts, there may be occasions when writing cannot be addressed the way these authors recommend and thus leave the teacher thinking they did not teach writing at all. Scrivener (2011) presents a continuum of the writing work in the classroom considering restriction, help and control offered to the student (Table 1), which may contribute to answering teachers’ doubts regarding what type of writing activity they assign.

Table 1: Scrivener’s continuum for writing work in the classroom (Scrivener, 2011, p. 235)

Writing is a complex activity in which cognitive and attitudinal abilities are involved with the purpose of creating a text to communicate in written form. In real contexts, like Mexico, it might not be possible to sustain the teaching of writing with strict theoretical foundations due to certain factors that may constrain this. For example, in public schools English is taught in three sessions a week, each lasting between 45 and 55 minutes. Also, the content of the English program is vast and some teachers have difficulties covering it all during each unit. Scrivener’s (2011) continuum may thus be of help for teachers to place their writing activities under a category that allows them to know how much restriction or control they offer to their students. The teacher may thus grade the writing work by starting off with controlled activities that lead to more unguided ones, achieving this way the communicative purpose of writing.

Writing skills

An important aspect to consider when teaching writing is the writing skills that are to be developed by the students. In this regard, Brown and Abeywickrama (2018) point out what they call micro-skills for writing, such as producing graphemes and appropriate orthographic and word order patterns, using grammatical systems and appropriate cohesive devices, expressing the same meaning in different grammatical forms, etc. Also, the authors mention macroskills such as using rhetorical forms and conventions of written discourse, accomplishing communicative functions of texts according to form and purpose, and using writing strategies, considering culture, among others. Regarding writing strategies, some of them are related to drafting, revising and editing written texts.

Some of those micro- and macroskills coincide with some of NEPBE’s specific competencies to be developed by students in Cycle 4 (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b) and are related to producing texts. Such specific competencies are: 1) use grammar, spelling, and punctuation conventions; 2) produce short, conventional texts that respond to personal, creative, social, and academic purposes; 3) recognize and respect differences between their own culture and the cultures of English-speaking countries; 4) use appropriate registers in a variety of communicative situations; and 5) edit their own or their classmates’ writings (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b, p. 103).

Other authors go further and call for developing effective writing skills in students. In this regard, Graham et al. (2016, p. 1) state that effective writing: “Achieves the writer’s goals […], Is appropriate for the intended audience and context […], Presents ideas in a way that clearly communicates the writer’s intended meaning and content […], Elicits the intended response from the reader…”.

Synthesizing what has been discussed about writing skills so far, students must develop skills that enable them to produce written texts according to writing conventions and purposes for writing, considering cultural differences and the appropriate genre. This reaffirms the view of writing as a complex process and not merely as putting spoken discourse down on paper.

Assessing writing

According to Nation (2009), some issues may arise when assessing writing; three of them are: 1) the purpose, 2) the student’s performance, and 3) marking. Regarding the first issue, the author states that the assessment of writing may be led by four different goals: 1) to motivate, 2) to improve the quality of writing, 3) to diagnose problems, and 4) to measure proficiency. When motivating is the goal, positive feedback can increase the amount of writing and the positive attitudes to it. When the goal is to improve the quality of writing, three of the things that need to be considered are the mode of feedback (oral, written, or both), the focus (product or process), and the form (comments, scale, checklist). Therefore, it is necessary to set specific learning objectives for writing tasks so that assessment is appropriate and helpful.

As to the second issue, which corresponds to the student’s performance, Brown and Abeywickrama (2018) present four categories that might guide teachers in this respect. First of all, when the assessment is primarily focused on form, the student’s written performance is imitative, with emphasis on the mechanics of writing through basic tasks such as the production of letters, words, punctuation and short sentences. When the assessment is concerned with the student’s ability to write sentences in which meaning and context are considered for determining correctness and appropriateness, the performance is intensive; important is to say that the tasks set are also more focused on form and are controlled, where the student writes sentences considering context, idioms, correct grammar, collocations, etc. As a third category, Brown and Abeywickrama present responsive performance, in which students are required to connect words into paragraphs, and to write two or three logically connected paragraphs; here, the student experiments with more freedom for expressing ideas. The fourth and last category is extensive performance, where the student is able to manage the processes and writing strategies to write essays, term papers, reports, theses, etc. Rather than focusing on form, purpose and organization of the ideas are considered.

Finally, the third issue in assessing writing relates to checking or marking. Giving too many marks may lead to discouraging students to write, while a lack of marking could prevent students from improving. Teachers must thus choose the appropriate strategies when marking their students’ written work. Scrivener (2011) offers some suggestions to mark students’ writing such as using green or blue pen, writing the correct answers in a margin, discussing the marks with students and agreeing on a grade, among others. Also, the author recommends using correction codes for the students to correct their mistakes themselves, arguing that this has benefits for them.

As well as teaching writing, assessing this skill is complex. Teachers must reflect on the purpose of the assessment, the students’ performance and their own response to the students’ written work. This latter is especially important since there is a fine line between discouraging students and motivating them to write.

Methodology

Type of study and research design

This study was descriptive since the aim was to discover aspects of interest to the researchers with the objective of interpreting them (Gento, 2004). The research methodology followed was the mixed methods approach, in which both qualitative and quantitative data were collected. Qualitative studies design is emergent, which means that the original research plan may change once the field work and the data collection begin (Creswell, 2009); moreover, Best & Kahn (2006) state that the main characteristic of this type of research is flexibility. This was precisely needed since the events in the context where this study was carried out could not be controlled by the researcher. On the other hand, quantitative research allows the researcher to measure, observe or document quantitative data to determine trends (Creswell, 2012; Hernández et al., 2014). In our study, the frequency with which the writing skill was worked on in the English class was to be determined.

As a result, it was considered that a mixed methods approach was appropriate because the combination of quantitative and qualitative data contributes to a better understanding of a research problem than any of such methods on their own (Creswell, 2012; Hernández at al., 2014; Leavy, 2017). Moreover, mixed methods allow the researcher to put emphasis on one type of data (Creswell, 2012). For this reason, an embedded design was chosen, since in this type of design one type of data is used to support the other type of data (Creswell, 2012; Leavy, 2017). In our study, qualitative data was necessary for the emergence of themes that helped present the information gathered, while quantitative data was necessary to determine the frequency of work on each language skill, including writing. Therefore, the emphasis was on qualitative data.

The method used for the present study was a multiple-case study, also known as collective case study, in which more than one case is studied. When using this method, the assumption is that it allows better comprehension and theorizing (Creswell, 2012). Also, Miles and Huberman (1994) said that carrying out a multiple case study lessens the probabilities of the events in only one case being entirely idiosyncratic. In this present study, there were six cases, this is, six teachers. The sample size was not relevant for the quantitative section of the study since the purpose was to determine the frequency of work on language skills from the lesson plans and from the observations.

Qualitative research design

Qualitative data collection techniques

The qualitative techniques for gathering information were non-participatory observation, qualitative document analysis, and an interview guide approach. As Creswell (2012) stated, through non-participatory observation, the researcher does not get involved with the participants and can register first-hand field notes from an advantageous place. In this study, the researcher sat in the back of the classrooms to be able to observe from a broad perspective.

As to document analysis, this is an unobtrusive research practice that can be used with a qualitative approach for investigating texts systematically (Leavy, 2017). This technique allows the researcher to observe and analyze existing documents useful for the study, as stated by Gento (2004). In the present study, the existing documents that were analyzed were the teachers’ lesson plans. This technique was necessary to classify the different activities in the teachers’ lesson plans according to the language skill being worked on.

As to the interview guide approach, Johnson and Christensen (2019) suggested that this type of interview allows the researcher to modify the order and the wording of the questions to be asked. However, as they state, because an interview protocol exists, the researcher is able to cover the same general topics and questions with all of the interviewees. This was helpful in this study because the researcher could rephrase the questions if necessary, or could reorder them, as recommended by Cohen et al. (2007), if one of the topics was mentioned by the teachers before being asked about it.

Qualitative data collection instruments

The data collected through the non-participatory observation technique were recorded in a field journal in the form of field notes. Such notes did not follow predetermined categories or themes. According to Best and Kahn (2006), field notes can take different forms, but they must be sufficient to recreate the observations and must contain direct quotations whenever possible. Besides this, the field notes taken must be those considered interesting to the researcher, as Gento (2004) states. These aspects were considered in the present study; the notes taken during fieldwork contained text as well as direct quotations. The information gathered was enough to analyze the work on the different language skills, including writing, and they were taken according to the interest of the researcher to achieve the purpose of this study.

Concerning the qualitative document analysis, there was no specific instrument used for this since the coding was carried out in the teachers’ lesson plans in Word documents. It was possible to have access to the lesson plans of five of the six teachers; the lesson plans included 10-12 weeks of class.

For the interview guide approach technique, an interview guide (interview protocol) was implemented, as suggested by Johnson and Christensen (2019). For this study, the interview protocol contained eight questions about 1) how lesson planning was carried out in the English class, 2) which language skills were considered in the lesson plans and worked on during class, 3) what type of activities were designed for the language skills worked on in the lesson plans and during class, 4) how the language skills were worked (either following a language integrated approach or working each skill in isolation), and 5) how the language skills were assessed and how many of them were assessed at a time.

Since the participant teachers’ level of English was not relevant for this study, and to avoid any misinterpretation either by the researcher or the participants, the questions in the interview protocol were in Spanish, the participants’ native language. The language of the interview in the mother language of the participants allows the researcher to collect quality data and to allow interviewees to be “comprehensive” (Elhami & Khoshnevisan, 2022, p. 3). The interviews were recorded. According to Cohen et al. (2007), doing this is unobtrusive but might limit the respondent. To avoid this issue in this study, the researcher asked the participants for authorization to record the interviews and explained to them that their data would be carefully treated to maintain anonymity.

Qualitative data analysis

The interviews were transcribed to conduct open and axial coding that allowed for the emergence of categories that could be arranged into themes. The themes resulting from this were: 1) writing activities, 2) resources, 3) assessment, and 4) frequency of work on writing. To validate the categories, both researchers carried out a comparison of categories. Afterwards, the interviews were translated into English to present the findings.

To confirm findings, triangulation and member checking were used (Cohen et al., 2007). Triangulation means corroborating the evidence in descriptions and themes from different sources (Cohen et al., 2007; Creswell, 2012; Hernández et al., 2014). Member checking, on the other hand, consists in requiring one or more participants to verify the accuracy of the report (Cohen et al., 2007; Creswell, 2012). In this study, triangulation was done by corroborating information from interviews, observations and documents, and member-checking was conducted by asking two participant teachers to verify the information in the findings.

Quantitative research design

Quantitative data collection techniques

The quantitative techniques for gathering information were quantitative (structured) observation and quantitative document analysis. As stated by Johnson and Christensen (2019), “Quantitative observation usually results in quantitative data, such as counts or frequencies and percentages” (p. 197). This type of observation was chosen because it was necessary to determine the frequency of work on the language skills during class, including writing skills. Quantitative document analysis is used to study any type of communication objectively and systematically (Leavy, 2017) by quantifying messages or content in categories and subcategories (Hernández et. al, 2014). In the present study, this technique allowed us to determine the frequency of work on the writing skill in the teachers’ lesson plans. For this, it was necessary to analyze the activities in the lesson plans and categorize them according to the language skill worked on.

Quantitative data collection instruments

Johnson and Christensen (2019) state that the use of checklists is usual when quantitative observation is carried out, as this was the case in the present study. These same authors say that data collection instruments in this type of observation are more specific. The checklist used in this study contained eight columns. The first column was to specify the number of session observed; then, there were four columns, one for each language skill and one more for the number of different skills worked on in each session that was observed. The last column was for general observations.

Similarly, a checklist was used for the quantitative document analysis in which the lesson plans were analyzed. The checklist contained nine columns. The first column was to specify the week number, and the second column was to specify the session within that week (maximum three sessions, as English classes in the context of this study take place three times a week according to the program). After that, there were four columns, one for each skill, followed by one column to specify how many different skills were worked on per session. The last column was for general observations.

Quantitative data analysis

The information collected through the checklists, both from quantitative observation and from quantitative document analysis, was quantified and graphed using Microsoft Excel. As to quantitative observation, the skills worked on during class observation were marked with number one (1) in the checklist under the corresponding language skill column. It is important to state that the number of activities to work on each skill per session was not determined. Therefore, the quantitative observation allowed us to determine the total number of sessions in which each language skill was worked on during the classes observed.

Regarding quantitative document analysis, the skills worked on in each session of each lesson plan were marked with number one (1). Similar to the quantitative observation, the number of activities to work on each skill per session was not determined. Therefore, the quantitative document analysis allowed us to determine the total amount of sessions in which each language skill was worked on in the lesson plans.

Sampling and participants

A purposeful sampling technique was implemented. Best and Kahn (2006) state that this type of nonprobability sampling “allows the researcher to select those participants who will provide the richest information, those who are the most interesting, and those who manifest the characteristics of most interest to the researcher” (p. 19). Considering this, six English teachers from five different public secondary schools were chosen. Hernández et al. (2014) stated that the minimal number of participants for a multiple-case study is six. Cresswell (2013) states that both quantitative and qualitative approaches can be used in explanatory, exploratory and descriptive case studies.

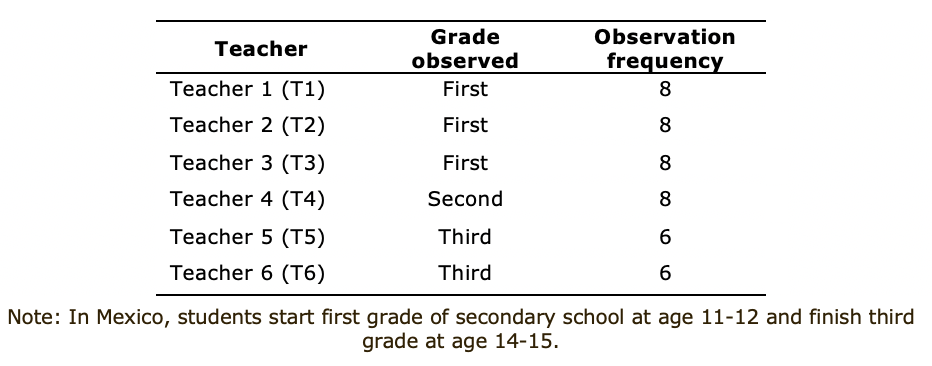

In this study, the researcher selected public secondary school English teachers. The participant teachers’ experience was from 2 to 12 years working in public secondary schools; as for their education, two of them had a master’s degree and the rest had a bachelor’s degree. Table 2 presents the grades in which each teacher was observed as well as the frequency; the researcher had no control over the grades to be observed for it was each teacher’s decision.

Table 2: Participant teachers: Grades and observation frequency

As can be observed in Table 2, T5 and T6 were observed six times while the rest were observed eight times; this was due to events that could not be prevented nor controlled by the researcher. As the English program states, teachers give three lessons a week, and the length of each lesson was from 45 to 55 minutes, depending on the schedule of each secondary school and on some other situations such as holidays.

In order to carry out the research, an oral informed consent process was followed with each of the participant teachers. The main reason to do so was the existence of a professional relationship with the six teachers prior to the study, since two of them had been trained by one of the researchers, and the other four had been colleagues in teacher training, either directly (in the same teacher training school) or indirectly (by receiving student teachers for professional practices in secondary schools). Each of the teachers received oral information about the objectives of the study as well as the methodology to be followed. Special emphasis was made on the following: 1) their teaching practice was not to be revealed, and 2) anonymity would be maintained. The six teachers gave their consent and accepted to be participants in the study.

Findings

In this section, findings related to the writing skill are presented into four themes: writing activities, resources, assessment, and frequency of work on writing. The extracts taken from the lesson plans, field journal and interviews are verbatim. Real names are not used.

Writing activities

Thirteen different activities were identified after analyzing the information. To present them, Scrivener’s (2011) continuum for writing work is used to show a broad panorama of how guided or unguided the activities may be. The activities fell into the first three categories: copying, doing exercises, and guided writing.

Copying

Three activities under this category were identified. The first activity was copying lists of vocabulary and grammatical items (prepositions, connectors, verbs, etc.), which was found in T1 and T2’s lesson plans, as this extract shows: “Make a list of prepositions and connectors. Draw what you like, love, hate, and don´t like. Students copy all information…”. Copying vocabulary was also observed in T2’s class.

The second activity was copying misspelled words correctly, which was observed during T4’s class, as this journal extract shows: “Dictation started […]. Teacher asked students to exchange notebooks for checking […]. Students had to write ten times the words they wrote wrong”. Even though this extract does not include the word “copy”, the students had to copy the correct words from their reader book.

The third activity was copying information, which included grammatical information or the meaning of specific words; this was observed in T2 and T4’s lessons. The following is a journal extract from the observation to T2: “The teacher projected a PowerPoint presentation about silent films and asked the students to copy the title in their notebooks”.

Doing exercises

In this second category seven activities were identified in which students were required to write words, phrases or sentences according to very specific instructions. The first activity was labeling images, which was found in T1 and T2’s lesson plans, as shown in the following extract: “Teacher explains activity on page 49. Students will label the pictures with words from the box”. Word and sentence dictation was the second activity identified; the following is an extract from T6’s lesson plans: “Dictation of several sentences of the same top 100”. This type of activity was also observed T4’s lessons, as well as it was mentioned by her in the interview.

The third activity was creating a word search or crossword puzzle; this activity was observed in T1’s lessons as well as in her lesson plans and those of T2 and T4; an example of this is shown in the following journal extract: “Then, the teacher gave instructions in English to make a word search with those words”. The fourth activity identified was answering questions or worksheets, which was observed in T2, T4, T5 and T6’s lessons. The following was observed in T2’s class: “Then, [the teacher] projected the questions that the students had copied. The students had to answer in their notebooks”. Besides this, activities of this type were found in T1, T2, T4, T5 and T6’s lesson plans; moreover, in the interview T6 stated that she considered answering worksheets as writing work.

Writing answers on the board was the fifth activity and it was observed in T4 and T5’s lessons; the following journal extract gives evidence of this in T4’s class: “Then, the teacher had some students go to the board to write the genres”. Also, this was found in T4’s lesson plans.

The sixth activity was writing/rewriting sentences. The following sentence writing activity was observed in T3’s class: “The students had to write a sentence saying the birthday of one classmate for each month”. This type of activity was also observed in T1, T2, T4, T5 and T6’s lesson plans, as this extract taken from T1 and T2’s lesson plans demonstrates: “Explain the students the verb to be, applying likes and dislikes. Example: I like an apple, She likes apples. Students will write sentences”. Also, this type of activity was mentioned by T3, T4 and T5 in the interviews when being asked about the type of writing activities that they carried out in class. The following extract is taken from the interview to T3: “… depending on the topic, [the activities] are usually sentences or I have them write in their notebook, […] which is basically what we do”. Rewriting sentences, on the other hand, was found in T4 and T6’s lesson plans.

The seventh activity in this category was completing texts, charts or conversations, which was found in T1, T2, T4 and T6’s lesson plans. The following extract is taken from T4’s lesson plans: “Teacher will explain the activity showing an incomplete conversation (page 11) about a teacher and a student. Students will write the conversation in their notebooks to complete in pairs the missing information”. This type of activity was also observed in T3 and T5’s lessons; the following journal extract is from T3’s lesson observation: “The teacher gave instructions […] to complete a chart. The topic was about community service”. In this activity, the students had to complete the chart with place, situation, solution, date and final solution to carry out a community service.

Guided writing

This third category of the continuum involves writing longer pieces of text; three activities were identified here. The first activity was writing opinions, which was found in T4’s lesson plans, as shown in the following extract: “Teacher will play a video about bullying. Students will watch it and write in their notebooks about the video and what they think about bullying”. The second activity was writing conversations or dialogues; this was identified in T1, T2, T4 and T6’s lesson plans. The following extract is taken from T1 and T2’s lesson plans: “Explain to students like and don’t like. Asking personal information about things. Practice writing a conversation asking a partner for likes and dislikes to present it to the class”. This type of activity was mentioned by T1 in the interview, as this extract shows: “… an activity I just did and they loved was writing and recording a conversation […]. They wrote it and recorded themselves, and we played it in the audio player so that everybody could listen…”.

The third activity was writing texts, which included products such as monologues, paragraphs, and triptychs. Activities of this type were identified in T1, T2 and T4’s lesson plans, as this extract from T1 and T2’s lesson plans shows: “Students copy all information and write a paragraph about likes and dislikes to read in front of the class”. Besides, this activity was mentioned by T4 and T5 in the interviews; the following extract is taken from T4’s interview:

They [the students] were coming to the front to read from cardboards, which were monologues; they first had to do a concept map of a situation that happened to them [with] wh- questions […] and they developed the story with that…

These findings suggest that the teachers focus mainly on activities that promote imitative performance on the part of the student, considering Brown and Abeywickrama’s (2018) four categories presented in this work. Students are required to write, for the most part, words or phrases through copying and doing exercises. As it can be observed, most of the activities were identified in the lesson plans; few of them were mentioned in the interviews or observed during class. Clearly, these findings reveal that most of the writing activities implemented do not aim to develop effective writing skills in students as Graham et al. (2016) suggest, where the students produce texts according to the intended audience and context, and where they clearly expose their intended meaning.

Resources

The term resource in this section refers to any object which was found to be used by students to produce written texts according to Scrivener’s (2011) continuum presented in this work’s writing activities section. Seven resources were identified. The first resource was the notebook, which was identified in T1, T2, T4, T5 and T6’s lesson plans, mainly in the materials or resources section. In the writing activities section of this paper (copying, doing exercises, and guided writing), an extract from T4’s lesson plan is presented where this resource is mentioned, specifically in the section Doing exercises in the activity completing texts, charts or conversations. Also, T1 and T3 mentioned it in the interviews, as can be observed in T3’s interview extract in this paper’s writing activities section, specifically in Doing exercises, in the activity writing/rewriting sentences. Finally, a notebook used for writing was observed in five out of six cases.

The second resource identified for writing work was the coursebook, which was observed in T1, T2 and T4’s lesson plans, as this extract from T4’s lesson plans shows: “T[eacher] will show three images or posters to the students. (Page 9, Yes, We Can! student book.) Students will talk about the message and answer the activity below”. T3, T5 and T6 said that they did not work with the coursebook; T3 considered it too advanced for his students, while T5 and T6 said they had not received enough books. Writing in the book was observed in T4’s lessons, as this journal extract shows: “The teacher gave instructions in English to do the exercise in the book”.

Worksheets (sometimes referred to as handouts by teachers) was the third resource identified; its use was observed in T5 and T6’s lessons, as shown in this journal extract from T5’s class: “The teacher explained the activity. The students had to read from the handout: ‘We are going to answer here’ […] The students talked in Spanish while answering the worksheet”. Also, this resource was observed in T6’s lesson plans under the term copies, and it was mentioned by her in the interview.

White sheets of paper was the fourth resource identified for writing activities. This resource was found in T1, T2 and T4’s lesson plans. The following extract is taken from T4’s lesson plans: “Students in a white sheet of paper are going to write an autobiographical anecdote”.

The fifth resource was the flipchart, sometimes referred to as bond paper by some teachers. It was found in T1, T2 and T4’s lesson plans, mainly in the materials or resources section corresponding to writing activities, such as this extract from T4’s lesson plans shows: “Students will make a Public service announcement about bullying, using colors, pictures, phrases, etc. Present to the class”; the corresponding materials list was as follows: board, book, notebook, bond paper, colors, and markers.

The sixth resource identified was the cardboard, as T4 explains in the following interview extract: “… as you saw that they went to the front to read their anecdotes, that they presented their cardboards” [... como viste que pasaron a leer sus anécdotas, que pasaron a presentar su cartulina]. The use of the cardboard for writing activities was observed in this same teacher’s class.

Finally, the board was the seventh resource identified, whose use was limited to sharing answers to exercises in the book or notebook. As explained in this paper’s activities section, this was observed in T4 and T5’s lessons. Also, it was identified in T4’s lesson plans, as shown in the following extract: “Students will write some sentences, and questions. Step to the front some students and write on board sentences to check statements”.

All the resources identified are paper-based. Even though this might be considered obsolete by some because technology is not on the table, Harmer (2007) recommends paper-based resources for working collaboratively to present main ideas in class. Also, Scrivener (2012) states that paper-based resources can be attractive for students because they are hands-on material, which contrasts with today’s continuous exposure to screens. However, it is also necessary to teach students how to write in real-world situations where digital technology is required so that the writing tasks become contextualized and meaningful to students.

Assessment

The lesson plans did not contain explicit information about assessment on writing, nor was an assessment on writing observed during class. However, three assessment practices for this language skill were identified in the interviews: written exams, vocabulary dictation and class projects. The first writing assessment practice was the written exam, as mentioned by T4 in the interview:

The exam would be only reading and writing, there are no exams for speaking and listening […]. When I apply exams, it is to evaluate the domain of knowledge on the topics covered and it is basically to read the question and answer the exercise.

From the excerpt, it can be inferred that T4 refers to reading questions and answering as reading and writing respectively. Thus, this type of writing falls into the category of doing exercises according to Scrivener’s continuum. This seems to be particularly focused on microskills of writing such as producing graphemes and appropriate orthographic and word order patterns, which were presented in the theoretical framework of this work.

The second assessment practice for writing was vocabulary dictation. This assessment practice was also mentioned by T4. The following extract gives evidence of this:

… first, I pronounce [the word] and they repeat, and afterwards, when we finish [pronouncing] the ten of them, I point at them and [the students] repeat on their own and I tell them, “We’re going to have dictation” […], then dictation is only listening and writing.

One more time, the teacher’s concept of writing seems to be related to producing graphemes and appropriate orthography in this case. Although Nation (2009) recommends dictation as a task to improve learners’ writing skills, the author presents this technique in such a way that it involves composing a text rather than isolated words. Similarly, Brown and Abeywickrama (2018) present dictation as an integrative testing technique where the student listens to a short text and writes what he or she hears.

Class projects was the third assessment practice identified. This assessment practice was mentioned by T3, T5 and T6 in the interviews. In the following extract, T3’s testimony is shown:

… in each unit or in each trimester different project products are required, […] projects focus on [students’]reproducing what they learned in class […] the focus would be to check structure […] how it was written and […]if it is good, neat, […] with aesthetic characteristics.

As it can be seen, T3 mentions one of the aspects that Secretaría de Educación Pública (2011b) considers is not writing: neatness. Harmer (2012) draws attention to writing neatly, especially for students whose first language script differs from English. In the context where this study was carried out this is not the case; thus, neatness may be left aside to give place to aspects that reflect the writing skill more accurately. On the other hand, the teacher mentions structure as one of the aspects to be assessed, which gives light on the possible consideration of genre when writing a text.

In general, these findings reveal that Nation’s (2009) goals for assessment (to motivate, to improve writing, to diagnose problems, and to measure proficiency) seem to be left aside when assessing students writing. Moreover, when improving the quality of writing is the goal, this author states that feedback, focus and form must be considered. In this case, these findings suggest that this latter might be considered up to some point but not the other two. A study by González (2021) reports that writing assessment training impacts positively on teachers’ assessment practices; if this is not the case for the participants in this study, that could be the reason why the teachers seem to address little, if any, attention to meeting the goals of assessment mentioned before.

The teachers in this study had around 35 students per group, and they had from four to ten groups each. T3, for example, had nearly 400 students in total. This makes assessment a challenging task. In fact, González (2017) claims that assessing writing in the classroom is difficult and requires knowledge of both the nature of the assessment and the tools that are available for carrying out this activity.

Frequency of work on writing

The last theme that emerged from the analysis was about how frequently writing was worked by teachers in comparison to other language skills. First, the teachers stated that writing was one of the skills more frequently worked on in their lesson plans, as this extract from T3’s interview shows:

…what I normally work more often in my classes, I think it would be writing and speaking […] I think [that] because they are the skills easier [sic] and the ones that are more frequently used daily, right? On a daily basis, it could be seen that way, then, I think that it is [with those skills] with which [the students] could be more in contact, right?

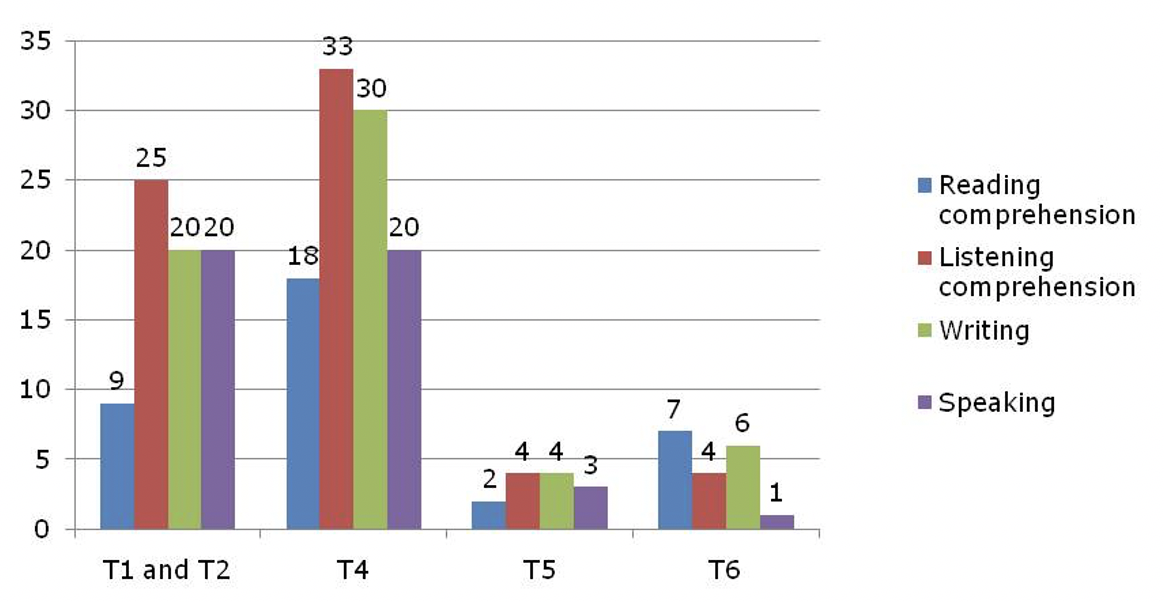

Besides T3’s testimony, T1, T4, T5 and T6 also stated in the interviews that they considered that work on the writing skill appeared more frequently in their lesson plans along with one or two other skills. These findings corroborate that to some degree, considering what was found in the lesson plans (Figure 1). The number of sessions in which writing activities appeared in the lesson plans was slightly lower than other skills in T1, T2, T4 and T6’s lesson plans.

Figure 1. Frequency of work on writing found in the lesson plans following Scrivener’s (2011) continuum and contrasting with other language skills

In order to obtain the frequency of work in each language skill, each of the teachers’ lesson plans was analyzed to count the number of sessions in which the language skills appeared; the number of activities for each skill was not determined. T1 and T2’ lesson plans contained 30 sessions; T4, 42 sessions; T5, 12 sessions (her lesson plan was organized weekly and not by sessions; it contained 12 weeks); and T6, 30 sessions.

It is also important to consider the following: 1) T1 did not provide any lesson plans and thus it was not possible to determine the veracity of his testimony; 2) T5’s lesson plan was broadly general and it was not possible to identify the language skill worked in all of the activities; and 3) T6’s lesson plans were also considerably general. Regardless of the fact that some of T6’s activities showed work on certain skills, most of them remained ambiguous as to who would do what, as the following extract from T6’s lesson plans shows: “Write ‘Top 100 words in books’”. In this activity it is not specified who would write the words.

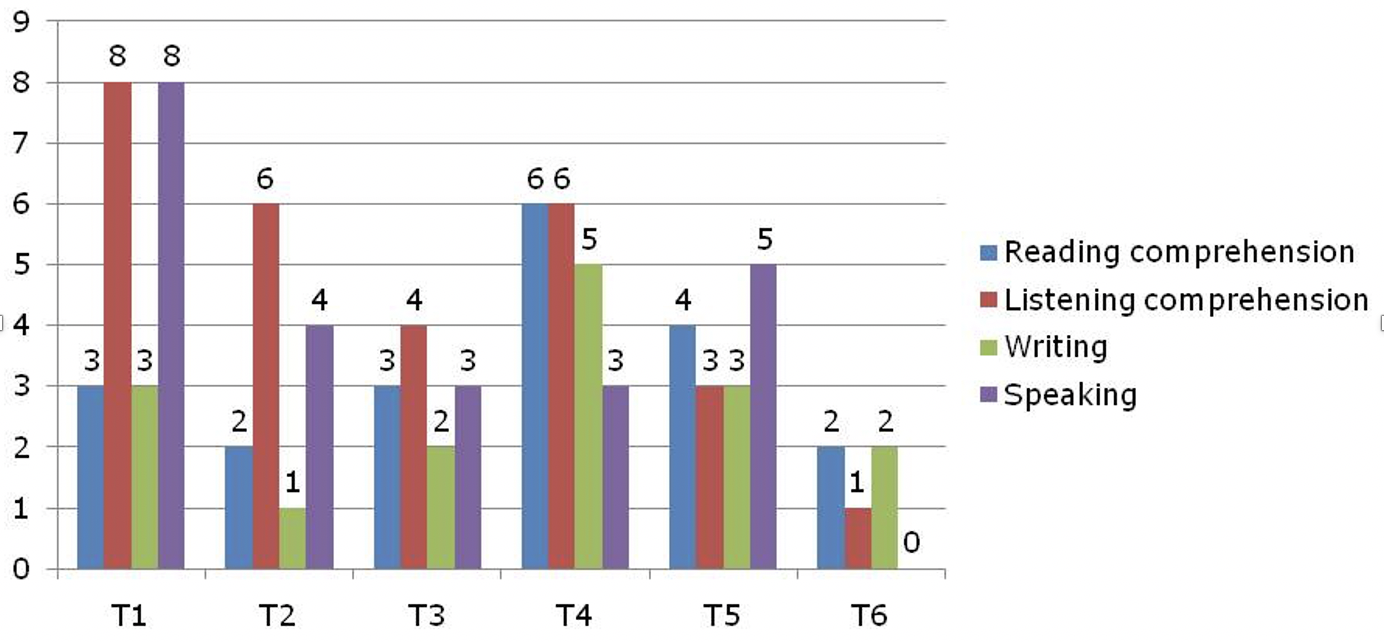

In relation to the language skills worked on in class, teachers said that they considered that writing was one of the language skills on which they worked the most; only T2 did not state this in the interview. Figure 2 presents the number of sessions that work on the writing skill was observed during class, and it reveals slight discrepancies between these findings and the teachers’ testimonies, except in T6’s case.

Figure 2. Frequency of work on writing observed in class following Scrivener’s (2011) continuum and contrasting with other language skills

As can be observed, these findings show a contradiction in relation to the frequency of work on the writing skill in class considered by the teachers and the actual work observed in class. This might be related to what the teachers consider as writing; however, another reason might be that teachers in general are not usually systematic as to the frequency of work in each language skill. One important aspect to point out here is that writing is one of the language skills that are mentioned in the lesson plans most frequently. However, most of the activities involve writing words, phrases or sentences and, therefore, do not aim at developing effective writing skills.

Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this study was achieved since we determined how writing is taught in five public secondary schools in a city in northwestern Mexico. Through the analysis of data, four themes emerged: writing activities, resources, assessment, and frequency of work on writing.

First, the findings of this research suggest that a good number of writing activities (7 out of 13) implemented by teachers can be categorized as doing exercises according to Scrivener’s (2011) continuum. Moreover, evidence suggests that formal writing prevails through doing exercises in which students were required to write one word, phrases, or sentences under controlled conditions. Even though the English programs in use at the moment of this study called for writing with a purpose (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b; 2017) and demand more guided writing, process writing ,and unguided writing, findings reveal that this was not completely addressed through lesson planning, class execution, and assessment. On the other hand, findings suggest that when guided writing was addressed, writing conversations, and writing texts such as paragraphs and monologues were most common.

As to resources for writing activities, evidence reveals that these were mainly paper-based, except for the use of the board for students’ sharing written answers to exercises. It was found that students were required to put written text down on white sheets of paper, cardboards, and flipcharts, and to answer exercises in the book or in worksheets. Evidence suggests that such answers tend to be one word, short phrases or sentences with limited creativity.

Regarding assessment on writing, it was found that this is not explicitly stated in the lesson plans revised. However, three assessment practices were identified through the teachers’ testimonies: written exams, vocabulary dictation, and class projects. Evidence suggests that the first two assessment practices tended to be form-driven rather than meaning-driven, which means that assessment tended to address aspects such as spelling, punctuation, and grammar instead of meaning and purpose for writing. Regarding class projects, results appear to demonstrate that other elements besides form were considered for assessment such as neatness and aesthetic qualities. In general, findings suggest that the main goal of work on writing was to measure proficiency rather than increase students’ motivation, amount of writing or positive attitudes towards this skill. Moreover, the writing tasks for students seem to enhance imitative and intensive (focused on form) performance.

Even though findings reveal that writing is one of the skills that appeared more frequently in the lesson plans and that it is worked on more often in class, evidence suggests that it is limited to doing exercises and little work is done for students to write larger pieces of text. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that at least one of the microskills mentioned in NEPBE (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2011b) is addressed: the use of grammar, spelling, and punctuation conventions. However, cultural references, purpose, and genre appear to be left aside.

Similar findings have been reported by Padilla González and Espinoza Calderón (2015). They carried out a multiple-case study in which four public secondary school English teachers participated in Aguascalientes, a state in north-central Mexico, and they found that the English lessons were mainly focused on the writing skill, with activities such as text reproduction. Similarly, but in high school, Castillo Loeza et al. (2019) report a study carried out in Yucatan, a state in southeastern Mexico, in which they found that translation and writing repetitions were activities applied in the English class. Such activities could be considered as doing exercises or guided writing according to Scrivener’s (2011) continuum.

Other studies give evidence of deficiencies in the writing skill of Mexican students from elementary to higher education (Backhoff Escudero, et al, 2006; Backhoff Escudero et al., 2013; Guevara Benítez et al., 2008; Rojas-Drummond et al., 2008). According to them, these deficiencies are due to traditional teaching in writing that focuses on reproducing texts and copying words and sentences rather than producing texts with a communicative purpose. Even though these studies were about Spanish as a mother tongue, they are related to the problem of writing in English as a foreign language, since Crespo and De Pinto (2016) claim that teaching and learning writing in the mother tongue has repercussions on the second language.

It is recommended that English teachers analyze their teaching and learning context in search for the design and implementation of better activities that help achieve the English program’s objectives. Even though having students write down on paper might be useful and appropriate, digital writing is also required in today society. Therefore, students need to learn to write texts with varied extensions according to style and purpose. If time is a constraint, Harmer’s (2007) recommendation of exposing students to different daily life writing styles might be useful. In other words, students could write simulations of instant messaging, emails, form filling for subscription to an online service, etc.

Another important aspect to consider is the number of students that the participant teachers had. As it was mentioned before, there were around 35 students per group, and teachers had from four to ten groups each. Therefore, assessing writing may become a titanic task considering that each teacher may have around 300 students. A solution for this could be collaborative writing, which is writing carried out in groups. Harmer (2015) claims that collaborative writing can motivate students; besides, the author states that this type of writing may include also research, discussion, and peer evaluation. Similarly, Nation (2009) recommends shared tasks, which is writing done in pairs or in groups of three or four students; the author says that this type of task is helpful for students who struggle to write individually. Moreover, he affirms that three advantages of shared tasks are that 1) they require little preparation by the teacher, 2) they reduce the teacher’s supervision, and 3) they reduce marking load.

Finally, this study had two main limitations. First, due to a lack of resources and time limitations, each participant teacher could only be observed a maximum of eight times. This is relevant since more important data could have arisen if observations had continued until saturation. Second, considering the design, findings might not be extrapolated to reflect the reality in such a wide context as the teaching of writing in English in Mexico. However, we consider that one contribution is that these findings might serve as a basis for designing quantitative studies that lead to generalizations on how writing is taught in public secondary schools.

References

Acuerdo número 20/12/16 (2016). Acuerdo número 20/12/16 por el que se emiten las Reglas de Operación del Programa Nacional de Inglés para el ejercicio fiscal 2017 [Agreement number 20/12/16 through which the operation rules of the National English Plan are issued for the fiscal exercise 2017]. Diario Oficial de la Federación. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5467931&fecha=28/12/2016

Backhoff Escudero, E., Peon Zapata, M., Andrade Muñoz, E., & Rivera López, S. (2006). El aprendizaje de la expresión escrita en la educación básica en Mexico: Sexto de primaria y tercero de secundaria [Writing skills learning in basic education in Mexico: Sixth grade in primary school and third year in middle school]. INEE. https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/P1D213.pdf

Backhoff Escudero, E., Velasco Ariza, V., & Peón Zapata, M. (2013). Evaluación de la competencia de expresión escrita argumentativa de estudiantes universitarios [Evaluation of university students’ argumentative writing skill competence]. Revista de la educación superior, 42(167), 9-39. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/resu/v42n167/v42n167a1.pdf

Best, J. W., & Kahn, J. V. (2006). Research in education (10th ed.). Pearson.

Brown, H. D. (2002). English language teaching in the “Post-Method” era: Toward better diagnosis, treatment, and assessment. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 9-18). Cambridge University Press.

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2018). Language assessment. Principles and classroom practices (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Castillo Loeza, A. C., Pinto Sosa, J. E., & Alcocer Vázquez, E. (2019). Perceptions of English language teachers from public high schools in Yucatán, Mexico. Lenguas en Contexto, 10, 33-42. http://www.facultaddelenguas.com/lencontexto/?idrevista=26#26.33

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education (6th ed.). Routledge.

Crespo, A., & De Pinto, E. (2016). El desarrollo de la escritura en inglés en la educación secundaria: una misión posible [Development of the writing skill in English in secondary education: a possible mission]. Revista Multidisciplinaria Dialógica, 13(2), 28-53. https://www.revistas-historico.upel.edu.ve/index.php/dialogica/article/view/4938/2557

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research. Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design. Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Davies, P. (2007). La enseñanza del inglés en las escuelas primarias y secundarias públicas de Mexico [English teaching in elementary and secondary schools in Mexico]. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(2), 13-21. https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=976

Elhami, A., & Khoshnevisan, B. (2022). Conducting an interview in qualitative research: The modus operandi. MEXTESOL Journal, 46(1), 1-7. https://mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=45957

Gento, S. (2004). Guía práctica para la investigación en educación [A practical guide to research in education]. Sanz y Torres.

González, E. F. (2017). The challenge of EFL writing assessment in Mexican higher education. In P. Grounds & C. Moore (Eds.), Higher education language teaching and research in Mexico (pp. 73-100). British Council Mexico.

González, E. F. (2021). The impact of assessment training on EFL writing classroom assessment: voices of Mexican university teachers. Profile Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 23(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n1.85019

Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L. D., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C. B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE). http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED569984.pdf

Guevara Benítez, Y., López Hernández, A., García Vargas, G., Delgado S., U., & Hermosillo García, A. (2008). Nivel de escritura en alumnos de primer grado, de estrato sociocultural bajo [Socioculturallly low first graders’ writing skills level]. Perfiles educativos, 30(121), 41-62. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2008.121.61037

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). Longman.

Harmer, J. (2012). Essential teacher knowledge: Core concepts in English language teaching. Pearson.

Harmer, J. (2015). The practice of English language teaching (5th ed.). Pearson.

Hayik, R. (2018). Promoting descriptive writing trough culturally relevant literature. In A. Burns & J. Siegel (Eds.), International perspectives on teaching the four skills in ELT: Listening, speaking, reading, writing (pp. 193-203). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2019). Educational research. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (7th ed.). Sage.

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design. Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. The Guilford Press.

McDonough, J., Shaw, C., & Masuhara, H. (2013). Materials and methods in ELT. A teacher’s guide (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Sage

Nation, I. S. P. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL reading and writing. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203891643

Padilla González, L. E., & Espinoza Calderón, L. (2015). La práctica docente del profesor de inglés en secundaria. Un estudio de casos en escuelas públicas [The secondary English teacher’s practice. A case study in public schools]. Sinéctica, 44. https://sinectica.iteso.mx/index.php/SINECTICA/article/view/164/157

Ramírez-Romero, J. L. (2009). Estado del conocimiento de las investigaciones sobre enseñanza y aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en México. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 51(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie5111928

Raimes, A. (1983). Techniques in teaching writing. Oxford University Press.

Rojas-Drummond, S., Guzmán Tinajero, C. K., Jiménez Franco, V., Zúñiga García, M., Hernández Carrillo, G. B., & Albarrán Díaz, C. D. (2008). La expresión escrita en alumnos de primaria [Elementary school students’ writing skills]. INEE. https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/P1D403-1.pdf

Scrivener, J. (2012). Classroom management techniques. Cambridge University Press.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2011a). Programa nacional de inglés en educación básica. Segunda lengua: Inglés. Fundamentos curriculares: Preescolar, Primaria, secundaria. Fase de expansión [National English program in basic education. Second language: English. Curricular foundations: Preschool, primary, middle school. Expansion phase]. SEP. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/16031/Programa_Ingles_Primaria_fundamentos.pdf

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2011b). Programa nacional de inglés en educación básica. Segunda lengua: Inglés. Programas de estudio 2011. Ciclo 4 [National English program in basic education. Second language: English. Study programs 2011. Cycle 4]. SEP.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2016). El modelo educativo 2016. El planteamiento pedagógico de la Reforma Educativa [Educational model 2016. The pedagogic approach of the educational reform]. SEP.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2017). Aprendizajes clave para la educación integral. Lengua extranjera. Inglés. Educación básica [Key learnings for an integral education. Foreign language. English. Basic education]. SEP.

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning teaching. The essential guide to English language teaching (3rd ed.). Macmillan.

Ur, P. (2012). A cours