Introduction

There is no doubt that English is a primary means of communication around the world, with the number of non-native English speakers exceeding that of native English speakers (Tran & Vu, 2023). Due to convenience and global mobility, English language use involves speakers from a variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds, especially given the wide acceptance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) or English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). In other words, the dichotomy between nativeness and non-nativeness should be more extensively analyzed. To improve the communication between students in intercultural learning settings, it is important that EFL learners develop intercultural communication (IC) and intercultural sensitivity (IS) as an ultimate goal of achieving communicative competence (Hymes, 1972). Crucially, EFL teaching and learning should expand its reach beyond EFL learners’ linguistic competence and accumulation of cultural facts. Additionally, EFL learning should develop learners’ sense of cultural understanding by assisting them in recognizing, understanding, and respect different cultures besides linguistic knowledge.

Open-door reforms have increased the number of Vietnamese people going overseas, in addition to foreign people coming to Vietnam (Pham, 2014). For a variety of purposes, English language proficiency has become important component to employability (Tran et al., 2023). Therefore, there is a growing need for Vietnamese higher education learners to have intercultural competence to navigate sociocultural contexts. Following a long-term commitment to developing English language education across the country, via the Project 2020, there has not been adequate research on how Vietnamese students perform IC (Vu, 2022; Vu & Dinh, 2021; Vu & Tran, 2023). This paper presents Vietnamese HE students’ IC progression through language learning. An IC case study was developed and implemented with the hope of learning about students’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagement in IC. A survey was developed following a review of the literature and interviews with students. The findings suggested that EFL students in Vietnam performed weakly in cognitive engagement, as opposed to relatively high in affective and behavioral engagement. Furthermore, it was noted that the sociocultural dimensions were responsible for differences in students’ self-rated IC levels, including gender, origin, medium of instruction, and year of college.

Following several previous publications (Chi & Vu, 2023; Mai, 2018; Vu, 2022), these papers offer meaningful insights by continuing to explore how the current understanding of student engagement in IC can be translated into teaching and learning practices. Said insights can also serve as a promising venue to enable policy makers, curriculum writers, and assessment developers to consider students’ cultural understanding and recognition of cultural differences. Such considerations may help assist EFL learners to efficiently develop their communicative competence and employability skills (Tran & Vu, 2023). The goals of this research are not limited to the demonstration of students’ language abilities, instead they include prompting EFL learners to reflect on whether they are competent to engage in real-life intercultural encounters.

Literature Review

Student engagement

Student engagement is an increasingly important topic in educational research, since it is a primary determinant of how well students perform in school. Kuh (2009) refers to student engagement in the context of higher education as students’ source of time and energy spent to translate activity experiences into their expected outcomes, as well as institutional encouragement for students to engage in those activities. Surrendering to the demands of modern economies, higher education institutions have paid more attention to initiating and developing policies and actions to develop academic and non-academic experiences for students to develop students’ knowledge and work-related skills so they can enter the workforce competitively.

Student engagement continues to attract research from behavioral, sociocultural, and psychological perspectives. Behavioral researchers discuss student engagement as a form of participation among the students who specifically aim to develop their learning outcomes (Krause & Coates, 2008). Sociocultural researchers believe contextual dimensions, such as cultural backgrounds, characteristics, motivations, and institutional policies and practices simultaneously influence engagement patterns in educational activities. Pham and Saltmarsh (2013) add that students’ behavior is unarguably driven by sociocultural values. Thus, without considering these factors, how students exercise their behavioral engagement cannot be well understood. Especially in unfamiliar contexts, students are expected to flexibly negotiate and adjust to their behavior appropriately. Psychological researchers share relatively similar views with the two other schools stated above. Hu and Kuh (2002) state that student engagement is associated with the quality of student efforts in educational activities. In the psychological perspective, there are three separate forms of engagement, including cognitive, affective, and behavioral. Fredricks et al. (2004) define cognitive engagement as a combined sense of self-regulation and learning sufficiency which enables students to strategize deep learning. Shuck and Wollard (2010) state that affective engagement relates to students’ feelings and beliefs while engaged in activities. For example, when engaged in activities, students’ optimism, pride, and resilience can grow because of their interests in the activities and their sense of belonging. Finally, behavioral engagement, beyond what Fredricks et al. (2004) indicate, involves the students who contribute to activities with effort, enthusiasm, and patience.

Intercultural competence in language learning

Culturally, many researchers (Baker, 2015; Deardorff, 2009; Gardiner & Kosmitzki, 2010; Nieto, 1999; Tesoriero, 2006; Vu, 2022) have contributed to the aspects of engagement when it comes to understanding IC. For example, Baker (2015) relies on a poststructuralist approach to define culture, arguing that culture is “a complex social system, as opposed to natural system, that emerges through individuals’ joint participation in the world, giving rise to sets of shared knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes and practices” (p. 71). Rather than over-reliance on cognitive understanding, which is solely about knowledge, culture should be regarded as a social discourse, practice, and ideology. Research indicates that learning a second/foreign language assumes learners’ use of the culture(s) in which that language is used (Crozet et al., 1999; Dörnyei, 2001; Marek, 2009). To effectively communicate a language with someone of differing cultural backgrounds, language users are expected to understand that person’s culture. According to Kramsch (1998) (cited in Özdemir 2017), “language expresses cultural realities” (p. 512). In other words, language and culture are interwoven (Kramsch, 1993; Liddicoat, 2015). More broadly, considering the globalized world, language learners are encouraged to expand their cultural boundaries, thus developing their ability to succeed in intercultural communication. To increase intercultural communication competence, students are advised to increase their intercultural sensitivity and intercultural competence while learning English, since communication in the real world is contextually influenced by culture (Zhou, 2011). Otherwise, students will become able to speak L2 well, but are not accustomed to cultural values, beliefs, and dimensions (Bennett et al., 2003). Fitzgerald (1999) explains that highly proficient users of English face a great deal of challenges and risks associated with misunderstanding and miscommunicating with Anglophone English speakers in t real-life encounters.

In educational research, many scholars believe intercultural sensitivity (IS) and intercultural competence (IC) are two separate dimensions, but these are usually seen as interchangeable. Hammer et al. (2003) argue that IS reflects individuals’ “ability to discriminate and experience relevant cultural differences” (p. 422). Similarly, Chen and Starosta (1998) refer to IS as their “active desire to motivate themselves to understand, appreciate and accept differences among cultures” (p. 231). Therefore, meaning that IS allows English EFL learners to recognize and respect cultural differences before fostering cultural identities. Bennett’s (1993) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) provides guidance to accurately reflect individuals’ reactions to cultural distinctions. The model presents a transition from an ethnocentric orientation, individuals who tend to deny or minimize existing cultural differences, to an ethno-relativistic orientation, in which cultural identities are well acknowledged. In particular, the first stage (between Denial and Defense) encourages individuals’ awareness of cultural diversity, while the second stage (between Defense and Minimization) reduces negative judgments. From the third stage (between Minimization and Acceptance) onward, individuals can respond to cultural differences more positively (the third stage:), develop desire towards the fourth stage (between Acceptance and Adaptation), and finally in the fifth stage (between Adaptation and Integration) enhance their sense of empathy and respect regarding cultural differences. Research has suggested that improved IS exercise greatly improves intercultural communication at multiple levels (Sullivan, 2003; Vescio et al, 2003; Weiner, 2006). Individuals can critically challenge their negative judgments by considering various external factors. Speakers are likely to negotiate, collaborate, and create relationships during interpersonal communication, rather than engaging in undesired conflict or retaliation. Most significantly, individuals seem to confidently facilitate positive attitudes when interacting and bridging intergroup communication, thus avoiding potential conflict.

As indicated above, IC emerges as a crucial component for speakers to navigate intercultural encounters (Byram, 1997). However, Alred et al. (2003) suggest that intercultural exchanges do not automatically result in speakers being intercultural because IC does not develop in a linear process. Alternatively, it is justified that being interculturalrequires speakers’ “awareness of experiencing otherness and the ability to analyze the experience and act upon the insights into self and other which the analysis brings” (Byram & Fleming 2003, p. 4). More specifically, it is simply understood that to have good language skills, being intercultural also asks speakers to have affective strength for negotiation skills (Jæger, 2001). Despite the vast literature on IC, its definition has not been agreed upon. According to Hymes (1972), IC is one of four drivers of communicative competence, which facilitates language learners’ knowledge of grammar and rules of use in cultural contexts. Bennett (1998a; 1998b) adds that IC encompasses the skills needed to facilitate effective intercultural exchanges. Fantini (cited in Lázár, 2015) defines IC as intercultural speakers’ abilities to show “respect, empathy, flexibility, patience, interest, curiosity, openness, motivation, a sense of humor, tolerance for ambiguity and a willing to suspend judgment” (p. 209). In support of Fantini (2000), Hammer et al. (2003) further argue that IS is a resulting condition of IC, in which speakers “think and act” in an appropriate way. After admitting that their prior approach severely limited IC to cognitive engagement as “an individual and trait concept” (p. 44), Spitzberg and Changnon (2009) view IC as “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who […] represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7). Spitzberg and Changnon (2009) exclusively investigate IC with regards to individuals’ achievement of communicative goals, communicative abilities, and personalized ways of communicating, without considering other necessary aspects inform IC development. Besides formulating IC into cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagement, Byram (1997) formulates an often-cited framework of intercultural (communicative) competence consisting of five related forms of IC. They include intercultural attitudes (interests, willingness, and readiness), intercultural knowledge (of self and the interlocutors), intercultural skills (of interpreting and relating; of discovery and interacting), and critical cultural awareness. This IC framework aims to explain the profound development individuals’ abilities to effectively communicate with others of diverse cultural backgrounds.

Vietnamese student engagement to develop IC

Tran et al. (2019) suggests that IC is very important to the employability of Vietnamese higher education graduates and can be developed through critical incident tasks which are communicative events that interlocutors find confusing or problematic but can be used educationally to develop IC by enabling learners to understand events from different cultural perspectives. Following exposure to CCT, learners appear able to understand communicative events in which there were various points of miscommunication. Furthermore, they show greater awareness of Eastern and Western communication. These positive outcomes seem to be accompanied by the IC representations that Byram and Fleming (2003) list.

Similarly, Truong and Tran (2014) explore the ways feature films in the language being learned can be used to facilitate intercultural competence growth among Vietnamese students. Data shows that feature films can be a source of sociocultural knowledge by helping learners understand the close relationship between language and culture. For example, watching an American featured film allows learners to explore American culture, as well as how English is used in cultural context of the film. The study suggests that learners can not only recognize and identity cultural differences, but also successfully engage themselves in intercultural exchanges to re-define their Vietnamese identities. The use of feature films as learning materials can allow learners to address cultural stereotypes by helping them to live in otherness. This shows that films can be considered as authentic materials useful in English language learning. In a similar work, Vu and Tran (2022) also found the strong impacts on the use of authentic materials on the development of IC among Vietnamese EFL learners.

Regarding the use of digital learning sources in Vietnamese higher education, Tran and Duong (2018) examined the effects of information and communications technology (ICLT) on Vietnamese learners’ intercultural competence. Findings suggest that ICLT can be effective to promptly facilitate learners’ intercultural and linguistic competence at the same time. Tirnaz and Narafshan (2020) replicate the ICLT findings in another Asian country by questioning whether intercultural TV advertisements can have a positive impact on Iranian learners’ IS. The mixed-method study indicates that TV advertisements can open a flexible classroom climate, evident by experimental groups performing better than controlled groups in recognition, acceptance, and respect towards cultural differences.

The Present Study

Research questions

As presented above, this mixed-method study will elaborate upon insights into Vietnamese students’ intercultural communication engagement. It is important to understand this issue since greater understanding will heighten the effectiveness of developing IC for Vietnamese higher education students. This paper examines the following questions:

Question 1: To what extent do Vietnamese college students engage in developing IC?

Question 2: How differently do Vietnamese college students engage in developing IC, depending on their demographic backgrounds?

Approach

This study used a mixed-method approach to investigate the issue by examining the changes in level, trend, and variability, according to students’ backgrounds (Creswell, 2012), including quantitative data from questionnaires and qualitative data from interviews.

Participants

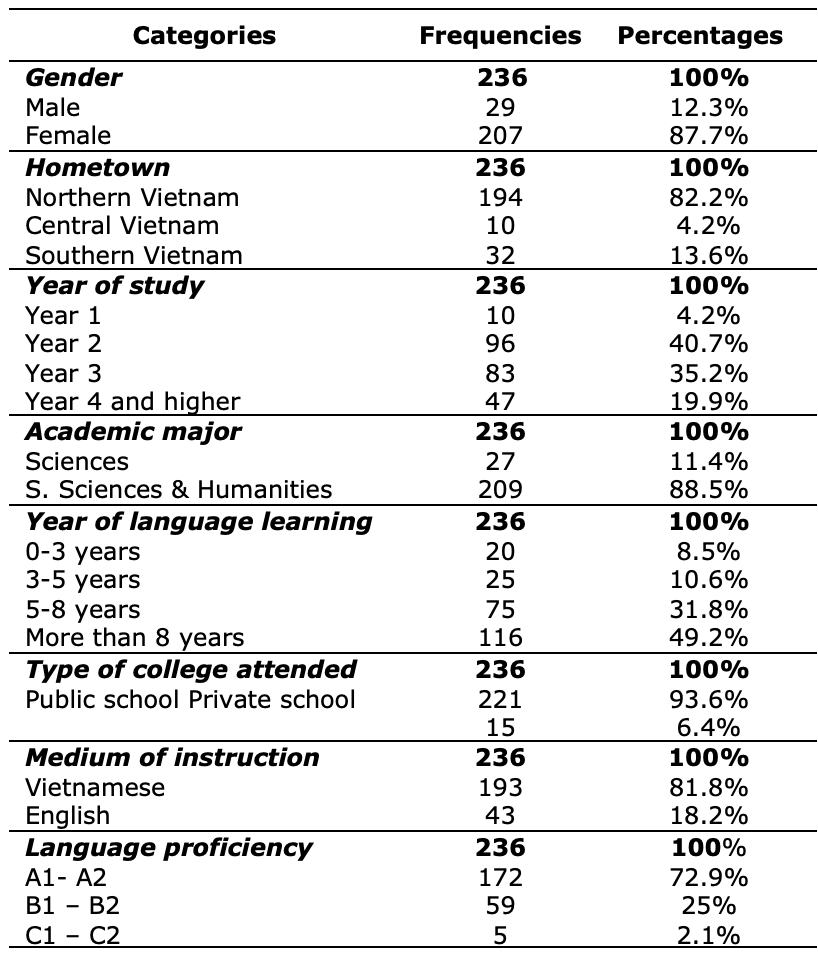

Two hundred and thirty six college students from various universities in Vietnam, ranging in age from 18 to 23, and hailing from different regions of the country, participated in the study. They were in different academic years at the time of the research, pursuing various majors (such as Sciences or Social Sciences and Humanities), and had varying levels of proficiency in the English language. Additionally, they were enrolled in programs where instruction was either in Vietnamese or English and attended either private or public institutions. Information can be available in Table 1.

Table 1: Students’ backgrounds

Data collection and analysis

Quantitative data (N=236) was gathered via digital questionnaire, which was developed based on the literature review, and initial interviews with college students in relation to their IC engagement. Despite not being the primary research participants, four volunteer female lecturers of English in the research sites were also interviewed to discover their college students’ engagement in IC. The interviewed teachers were chosen randomly from the research’s professional network. Four of them were between 35-45 years of age, having from eight years or more of experience, teaching both General English and Academic English for the English-major and non-English major students in public universities. The 45-to-60-minute interviews were primarily based on their knowledge and understanding about IC and what instructional techniques were employed to help their students engage to develop IC within classrooms and beyond.

Quantitative data was collected over three weeks, from July 12th to August 10th, 2020, using the snowball sampling technique (Browne, 2005). Students that the researcher knew and then other students at the same institution or from other institutions were invited. The participating students were mostly based in Hanoi City. In the questionnaire, participants were well informed of the research purpose and rights to withdraw their response at any time. The participants were required to submit consent forms as part of the survey; thus, their completion of the questionnaire means they agreed to voluntarily partook in the research project. All interviews were carried out in large cities in Vietnam. The data used to respond to the research question included: (1) participating students’ demographic information, and (2) 20 items which students were asked to self-rate their IC levels on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 denoting “very weakly” and 5 denoting “very effectively”.

A total of two hundred and sixty-one participants responded to the distributed survey, but 236 surveys remained for data analysis after removing incomplete surveys, refused invitations, and outliers. The data was processed via the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Demographic information is presented in Table 1. Data was analyzed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), followed by descriptive analysis with Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD). To explore differences between cultural backgrounds in participants’ self-rated IC, including their cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagement, inferential analysis was performed with Mann-Whitney U Test and Kruskal-Wallis H Test, because the statistically normal distribution was not fully reached.

Then, those who completed the survey were invited to attend the structured interview in thirty minutes. They were informed of the purpose and agenda of the interview via email and accompanied by the interview questions. They could reject their attendance, by simply responding to the invitation email. As a result, ten students volunteered to join, including ten male and ten female students. In the following, we will note their pseudonyms by using “M1, M2, …, F1, F2…”, in which M stands for Male and F for Female with 1 to 5 for the number of each student participant.

Findings

What are the engagement levels of Vietnamese HE students in intercultural communication?

Based on PCA findings, the internal consistency was very high (r=0.959) and the total-item correlation rates ranged between 0.27 and 0.67, meaning items were uni-dimensional (Osborne & Costello 2009). Additionally, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test outcome was 0.948 (Chi-square: 4020.07; df=190; p<.05), higher than the minimum acceptable KMO of 0.06 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Thus, this KMO value shows the effectiveness of extracting the variables into separate principal components. However, since items 10, 14, 16, 18 had two or three loadings that were not 0.2 apart, it was decided to remove them from analysis and re-conduct the PCA tests. According to the new analysis, the internal consistency appeared to be very high (r=0.946) and correlation rates ranged between 0.27 and 0.67, meaning items were uni-dimensional (Osborne & Costello, 2009). Furthermore, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test outcome was at 0.936 (Chi-square: 3049.110; df=120; p<.05), higher than the minimum acceptable KMO of 0.06 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Thus, it also proved that this KMO value proposed is effective enough to extract the variables into principal components.

When the PCA was completed, the data showed that three principal forms of student engagement were extracted based on the Eigenvalue greater than 1.0 with varimax option. Together, it explained a total of 73.99% of the variance, with loading for each item from 0.01 to 0.89 (Appendix 1). The resultant scale with three components regarding engagement to develop IC is as follows: Cognitive engagement (5 items; r=0.884, variance explained: 11.06%), Affective engagement (4 items, r=0.927, variance explained: 7.2%), and Behavioral engagement (6 items, r=0.931, variance explained: 55.69%).

Descriptive statistics were considered, and the means and standard deviations were calculated regarding students’ (1) levels of cognitive engagement, (2) levels of affective engagement, and (3) levels of behavioral engagement. Seeing as a five-point Likert scale was used to collect data, the framework that follows was applied to measure the IC levels, ranging: Very weak (1.0-1.8), Weak (1.8-2.6), Good (2.6-3.4), Excellent (3.4-4.2), and Very Excellent (4.2-5.0). The results showed that out of three principal components of student IC engagement, affective engagement was ranked the highest (M=3.04; SD=3.76), followed by behavioral engagement (M=2.59; SD=1.02), and then cognitive engagement (M=1.84; SD=0.98).

To support those statistical findings, some qualitative data from student interviews that were found closely aligned with the students’ reflections were included. First, it was interesting to find that students were happy about their growing affective engagement when increasingly exposed to various learning activities that encouraged them to think more about their own cultural values in addition to learning about the those of others. For example, F1 said that “my English teacher innovated her teaching curriculum and inspired us to collaborate while her efforts to include our ideas, such as our preferences regarding academic contents”. Similarly, another reported that “despite our response to the previously designed syllabus, I had a lot of space to work with my teacher who listened actively to us and we were excited about our shared voices. We understood each other”. In this sense, it is meaningful to recognize that voice is deemed important when it comes to developing affective engagement among EFL learners in Vietnam (Chi & Vu, 2023), which appears as a very new practice in the traditional EFL classes.

Contrary to popular belief, the interviewed students admitted that they were fully provided with sufficient of knowledge in relation to the culture they would be needing in the future, for example general knowledge about the structure of future companies where they would work or I environment where they were expected of to perform. However, their cognitive engagement was substantially limited. One male student (M3) asked:

How can we engage with developing our knowledge in a sensible and successful way while we are forced to consume a large amount of boring information of which we are unable to understand the importance and of which we cannot imagine how it relates to my future work?

The F4 student also added that “I recognize that my affective engagement was shown to improve because I was impressed by my instructor’s use of innovative pedagogies in teaching. I now consider that the instructors considered our perspectives and we collaborated to make decisions on what we learn and how to learn well”. It was also noticed that most students were considered as passive learners within their past 12 years in high school and until the time of the interview, so it should spend sufficient time familiarizing themselves with how well to engage in cultural development. Firstly, they need to establish and develop cognitive engagement through cultural knowledge of themselves and others. Then, they need to have positive intercultural affective engagement, meaning that they need to have positive attitudes about cultural knowledge which can then make them feel positive in findings ways to comprehend and appreciate cultural differences in learning and working contexts. However, if there is a gap between their cognitive and affective engagement, this may challenge their capabilities to adapt themselves in intercultural settings of academic or professional environments. However, my findings showed that the students’ cognitive engagement seemed to largely decide their behavioral engagement in intercultural communication.

Simultaneously, it is important to understand how the students develop their intercultural behavioral engagement. From my findings, the students seemed to have low levels of behavioral engagement. Some students (such as F1) shared that:

while I am interested in learning cultural differences, I struggled to use my cultural understanding to communicate with others in some life events.

Another student (M5) stated that:

to define how to engage myself behaviorally in intercultural settings is my obstacle. I wish that someone could inform me of how to transfer my affective into behavioral engagement.

To what extent do Vietnamese students’ engagement levels in intercultural communication differ according to their backgrounds?

Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to check two groups of students according to gender, course medium of instruction, and academic major. Of the three investigated forms of student engagement, data findings showed that there were no statistically significant differences between science students and social science students. Moreover, the difference between students currently studying at public universities and private universities was at an insignificant level of p>0.05. However, significant differences were not found in two groups of students coming from academic backgrounds (e.g., majors) and language used as medium of instruction.

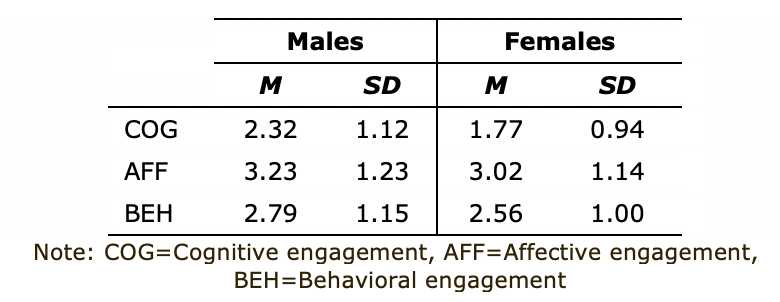

Note: COG=Cognitive engagement, AFF=Affective engagement, BEH=Behavioral engagement

Table 2: Engagement levels according to gender

Data findings by gender (Table 2) showed significant differences between self-rated levels of student engagement in IC. It was observed that male students (M=2.32; SD=1.12) performed better than female students (M=1.77; SD=0.94) in cognitive engagement (U=2151, z=-2.475, p=0.01). However, there were no statistically significant differences between students in affective and behavioral engagement (p>0.05).

Referring to these statistical findings, it was qualitatively revealed that students were likely to perform intercultural engagement influenced by their familial and communal cultures, with one male student (M5) saying that:

[he] tend[s] to imitate his intuition of making decisions more strongly than [his] female colleagues due to his privileges to have his voices counted towards a family decision.

He also said:

[he] seemed to become dominant in his teamwork, when his strength of knowledge made him able to convince others to follow [his] suggestions rather than discuss what was inappropriate and arguable with his teammates.

Similarly, another female student (F5) felt pessimistic about finding a job since she “felt inferior because Vietnamesemale students were very aggressive”.

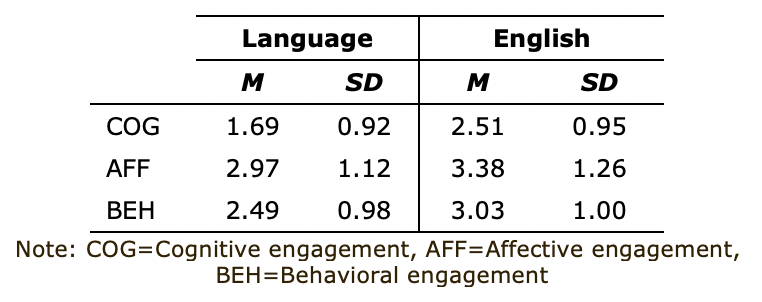

Note: COG=Cognitive engagement, AFF=Affective engagement, BEH=Behavioral engagement

Table 3: Engagement levels according to medium of instruction

There were statistically significant differences in all forms of student engagement (Table 3) between the two groups of students whose classes were taught in Vietnamese or in English. In terms of cognitive engagement, there was a statistically significant difference, with English (M=2.51; SD=0.95) being greater than Vietnamese (M=1.69; SD=0.92) at U=6109.5, z=4.852, p=0.000. Similarly, a statistically significant difference was seen in affective engagement between Vietnamese (M=2.97; SD=1.12) and English (M=3.38; SD=1.26) at U=5072.0, z=2.286 (p=0.022), as well as affective engagement between Vietnamese (M=2.49; SD=0.98) and English (M=3.03; SD=1.06) at U=5462.5, z=3.249, p=0.001.

Qualitatively, it was recognized that, to develop IC, seven out of ten interviewed students found empowered to speak up and engage affectively with learning experiences which involved contents about cultures from both the groups of native English speakers and non-native English speakers. For example, a student (F3) reflected that:

it was inspiring that my very little idea was thoughtfully integrated as a topic for our class to develop. The topic was about whether a female can be a leader in the country.

Out of those seven students, only four of them were concerned about their intercultural cognitive engagement. The other students tended to spend more time during their degree program exploring and understanding how their major-related knowledge contents is in the real work scenarios. They expected that the major-related knowledge to be learned in the program should be culturally sensitive and professionally relevant.

More importantly, it is also relevant to recognize their behavioral engagement as their production of personal and work-related identities. It is obvious that neglecting their abilities of behavioral engagement is a danger to their professional achievement, including lowering competitive advantage and failing to sustain employability. This is confirmed by three students (one male: M3 and two females: F1 & F5), who expressed their desires to feel prepared before seeking employment in their final year of study. Students seemed very anxious about the lack of behavioral engagement in developing IC.

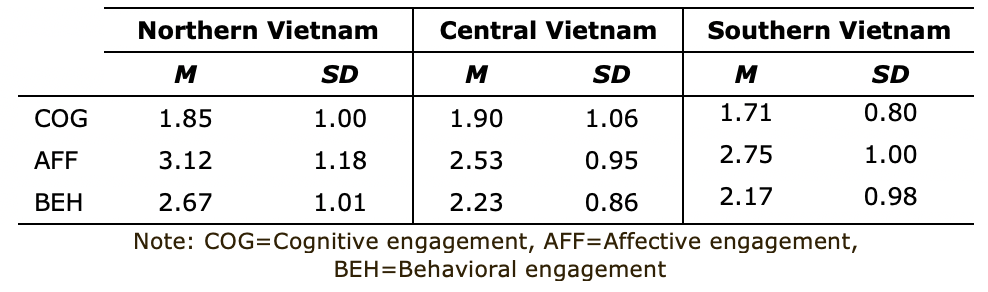

Note: COG=Cognitive engagement, AFF=Affective engagement, BEH=Behavioral engagement

Table 4: Engagement levels according to hometown

Kruskal-Wallis tests were run to explore whether the self-rated IC levels differed depending on students’ hometowns, current academic year, and language proficiency. At a p<0.05 level, data findings revealed that there were statistically significant differences in behavioral engagement between students coming from Northern, Central, and Southern Vietnam (χ2(2)=8.141, p=0.017) (Table 4). Subsequently, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s (1964) procedure. A Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was made with statistical significance was accepted at the p<0.017 level. This post hoc analysis revealed statistical differences in the self-rated IC levels of behavioral engagement between Northern Vietnamese students (M=2.67) and Southern Vietnamese students (M=2.17) (p=0.009), but not in any other group combinations. The qualitative findings were quite sensitive when it comes to the students’ differing responses in accordance with social groups and distinguishable cultures. While the qualitative findings were seemingly consistent with the cognitive and affective engagement as observed in quantitative findings, there was little information on behavioral engagement. However, one student (F2) asked:

how can I collaborate successfully with my colleagues who come from different cultural backgrounds and who follow very distinctively ways to relate to others’ ideas?

This question has opened the possible need to discover many fresher insights into research on IC in the Vietnamese context in conditions when English is used as a foreign language in fostering Vietnamese college-level students’ intercultural engagement.

Note: COG=Cognitive engagement, AFF=Affective engagement, BEH=Behavioral engagement

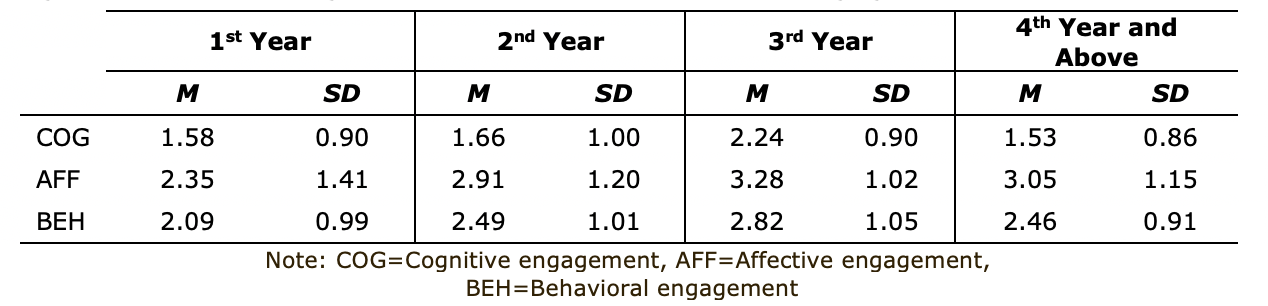

Table 5: Engagement levels according to year of study

At a p<0.05, data findings revealed that there were statistically significant differences in forms of cognitive engagement (χ2(3)=22.814, p=0.000) and behavioral engagement (χ2(3)=8.305, p=0.04) among four groups of students who were currently in different years of college (Table 5).

In cognitive engagement, pairwise comparisons were subsequently performed using Dunn’s (1964) procedure. A Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was made and statistical significance was accepted at the p<0.0083 level. This post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the self-rated IC levels between the 2nd-year students (M=1.66) and 3rd-year students (M=2.24), but not in any other group combinations. To explain this difference, a student (M4) explained:

transition from the second to third year was remarkable, moving from the general to major-specific subjects. I tended to think more about how to drive my academic learning so that it can be positively meaningful as I am required by the major-related courses.

Regarding behavioral engagement, post hoc analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between any group combinations despite its statistical significance in general. However, qualitative findings were unavailable to unfold this aspect, thus serving as a limitation. Opposed to this result, in terms of affective engagement, qualitative findings were sufficient in a way that the eight students were found increasingly motivated and inspired to develop their sense of interculturality for the sake of their future career and meaning of life. They used adjectives to this experience: important, urgent, practical, applicable, useful, helpful, positive, impactful.

At p<0.05, data findings revealed that there were statistically significant differences in all three forms, cognitive engagement (χ2(2)=48.791, p=0.000), affective engagement (χ2(2)=15.952, p=0.000), and behavioral engagement (χ2(2)=24.793, p=0.000) among three groups of students with different levels of language proficiency. Pairwise comparisons were subsequently performed using Dunn’s (1964) procedure. A Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was made with statistical significance accepted at the p<0.017 level (Table 5). Besides the quantitative findings as discussed as follows, there were consistently unclear and less patterned qualitative findings that impacts our understanding of how students of different language levels performed their engagement in IC. Therefore, these have offered valuable room to be investigated in future research.

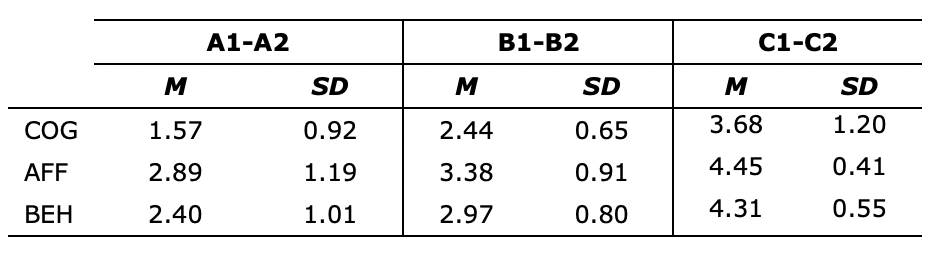

Table 6: Engagement levels according to language proficiency

In the first dimension of cognitive engagement, post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the self-rated IC levels between the beginning-level students (M=1.57) and advanced-level students (M=3.68) at p<0.01, between the intermediate-level students (M=2.44) and advanced-level students (M=3.68) at p=0.001, but not in any other group combinations.

About the second dimension of affective engagement, post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the self-rated IC levels between the beginning-level students (M=2.89) and advanced-level students (M=3.38) at p=0.019, between the intermediate-level students (M=3.38) and advanced-level students (M=4.45) at p=0.005, but not in any other group combinations.

In the last dimension of behavioral engagement, post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the self-rated IC levels between the beginning-level students (M=2.40) and advanced-level students (M=4.31) at p=0.001, between the intermediate-level students (M=2.91) and advanced-level students (M=4.31) at p=0.001, and between the beginning-level students (M=2.40) and advanced-level students (M=4.31) at p=0.039.

Discussion and Conclusion

As a result of the global intercultural age and flexible mobility, this article has examined the current levels of student engagement in IC in EFL language education in the wake of the Open-door reforms in Vietnam? This study examines self-rated scores of students’ levels of IC engagement in the context of Vietnamese higher education. Like some previous works, the findings show that developing IC can be classified into intercultural cognitive engagement, affective engagement, and behavioral engagement (Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009; Vu, 2022; Vu & Dinh, 2021). From the findings, they showed that the participating students responded very slowly to developing their cognitive engagement, but more efficiently with affective and behavioral engagement. Certain dimensions of social context (student gender, hometown, instruction medium, year of college, and language proficiency) were found to be responsible for these differences (Vu, 2022; Vu & Dinh, 2021). This section will discuss the findings in relation to how these sociocultural attributes impacted levels of student engagement in IC.

Theoretically, this study examined three forms of student engagement in IC, as supported by many researchers in the field (i.e., Byram, 1997; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009; Vuksanovic 2018). It was quantitatively observed that students’ cognitive engagement levels in IC were relatively low (M<2.6), which shows a stark contrast to the expectation that EFL learners perform better through factual accumulation (Tran & Duong, 2018). On the contrary, EFL students were found to be very positive in expressing their attitudes towards intercultural exchanges and interactions, which is evident that the observed levels were larger than M=2.6. It was surprising that this group of students was actively engaged in behavioral engagement to develop IC since they appeared to be able to behave react well to their exposure to otherness(Bennett; 1997; Byram, 2007; Byram & Fleming, 2003). According to Byram and Fleming (2003), these optimistically positive observations suggest that EFL learners try to become intercultural, rather than simply engaging in intercultural encounters which develop their IC.

Gaps were identified between combinations in relation to student engagement. Research might be able to explain why cognitive and affective engagement do not translate into behavioral engagement. However, in the present study, IC manifested itself in a way that students became more engaged behaviorally than cognitively, which is similarly found in some other studies (Vu, 2021). This could be attributed to the fact that these Vietnamese students were more likely to look for alternative learning approaches to develop their levels of IS as part of their long-term commitment to develop IC. Some forms of learning could be used as authentic learning environments, as reported by some scholars (Tirnaz & Narafshan, 2020; Truong & Tran, 2014; Vu & Tran, 2022). In those studies, it was seen that EFL learners could grow their sense of IC and use various learning sources, which offered them a better understanding of real-life interactions (Truong & Tran, 2014; Vu & Tran, 2022) and helped them recognize communicative events that asked them to identify and distinguish between problematic and non-problematic communication (Tran et al., 2019; Vu & Dinh, 2021). This suggests that there should not be an abundance of cultural facts to overwhelm EFL students in classrooms. It is because they may be faced with real-life intercultural encounters and find solutions to overcome challenges (Tran & Vu, 2022). In terms of interactions between affective and behavioral engagement, Deardorff (2009) revealed interesting findings about students’ willingness to keep themselves open to and respect cultural differences. As reported, EFL learners seemed to show their positive affective engagement in interculturality, including interest, willingness, and readiness to identify cultural differences, as required for intercultural attitudes (Byram, 1997). Affective engagement was positively ranked between M=2.75 and M=3.23, EFL students impressively perceived that culture is dynamically changing over time, instead of consistently unchanged regardless of relation to native or non-native English speakers (Bennett, 1997; Byram, 1997). Students have high levels of intercultural behavioral engagement, so they ultimately had great levels of affection (Byram, 1997; Jaeger, 2001). In this sense, it may have resulted in opportunities to study, work, or travel overseas thanks to their IC skills (Tran et al., 2023; Chi & Vu, 2023).

Based on the findings above, there are some implications in support of EFL teaching and learning. EFL students are now exposed to intercultural encounters more than in the past, as they are integrated into various traditional academic forms (such as lectures) and innovative non-academic learning (such as learning while watching foreign-language videos or listening to foreign music, e-learning, and social and extra-curriculum activities). Consequently, following the literature that combines with this study’s findings about the IC development in higher education learners, IC serves a promising aspect for EFL learners in Vietnam to have for addressing their intercultural knowledge, attitude, and skill gaps. And this must be noted by institutions and employers’ perspectives. Therefore, higher education institutions need to work continuously on providing students with diverse opportunities to improve and develop IC as part of the communicative competence in general (National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project, 2006) to improve their work-related skills (Tran et al., 2023; Tran & Vu, 2023).

Some differences in self-rated IC levels could be found between student identities. The study indicated that male students outperformed female students in cognitive engagement. In this sense, according to the Confucian culture in Vietnam, a disparity between gender roles is prevailing as women usually have to compromise their study and work for their house duties (Nguyen et al. 2016). Some other studies (Vu, 2022; Vu & Dinh, 2021) supports the need of investigating whether that male and female undergraduate students may react very differently to openness to experience, class attendance, and academic progress. Woodfield et al. suggest that EFL male students are far better equipped with a sense of openness after they are exposed to intercultural encounters. On the other hand, female students seem better than males at sustaining their motivation and openness to learn. The difference could be explained by the fact that male students, because of newly engaging themselves in intercultural encounters, are very active to progress cognitive engagement at a faster speed than female students (Vu & Dinh, 2021). Secondly, this study’s findings revealed that students largely exposed to English as a medium of instruction perform in a better way compared to those with of Vietnamese as a medium of instruction, which is consistent with the work by Vu (2022). In EFL classes, it is necessary to encourage English to be used predominantly, even though some research argues for the inclusion of native languages. The encouraged use of English in EFL classes could potentially help EFL learners further their acquisition of language rules and cultural facts in an endeavor to deeply understand sets of cultural attitudes and behaviors (Moeller & Nugent, 2014; Sinicrope, et al. 2012). It is not to say when English as a medium of instruction (EMI) is largely included, that the culture fails to be learned and acknowledged by students. Rather, it is true to say the predominant use of foreign language in EFL classes can both improve their language abilities and IC (Vu, 2022). Thirdly, consistent with the enormous impacts of EMI, this study’s statistic findings suggested that the EFL students can engage to better develop IC if they possess higher levels of language proficiency, which reveals similar findings in other works (Vu, 2022). Although Mighani et al. (2020) do not find a between EFL students’ language proficiency and IC level. This could be because learners with lower levels of proficiency cannot manage to understand a range of sophisticated linguistic features in language use, with limited vocabulary and grammar so they tend to avoid accessing high-level cultural materials in English (Vu & Dinh, 2021). Fourthly, according to the data, the freshman students did not have a good level of IC compared to more advanced students, especially given their lack of cultural exposure to new learning environments, leading to low IS and IC (Brooker et al., 2017).

This study suggests that sociocultural factors have influenced Vietnamese learners to a certain extent. Student engagement in developing IC is heavily influenced by gender, hometown origin, year of college, language proficiency, and medium of instruction (Vu, 2022). Based on quantitative findings, it is seen that cognitive engagement was very low compared to other forms of engagement, thus universities should pay more attention to addressing this gap. It is very crucial that EFL teachers dedicate more time to teaching culture using more culturally responsive strategies so that students can develop IC in a sustainable manner. Moreover, EFL teachers need to diversify instructional approaches and materials to relate to students’ cultural backgrounds (Chi & Vu, 2022), so that the students can understand that what they learn is relevant, meaningful, and purposeful. For example, they can develop authentic materials and establish experiential learning in support of their EFL learners’ growing sense of IS with adaptability, empathy, and mutual respect (Byram, 1997; Vu & Tran, 2023). Learning input can be aligned with in-class and out-of-class experiences. Moreover, students have an equal role in informing their EFL teachers about their personal inspirations, motivations, and goals, so that teachers and learners can together collaborate to co-design the instructional objectives and plans so that the desired goals can be fully achieved. As IC is a sub-dimension of communicative competence (Hymes, 1972; Tran & Vu, 2023) that belongs to employability skills (Tran et al., 2023), it is imperative that students closely examine their career plans and design how to translate those plans into realistic actionable steps, thus allowing EFL learners can increase their competitiveness in the labor market.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the professionals who helped improve the questionnaire and all student participants who agreed to complete the surveys and the interviews.

Reference

Alred, C., Byram, M., & Fleming, M. (2003). Intercultural experience and education. Multilingual Matters.

Baker, W. (2015). Culture and identity through English as a lingua franca: Rethinking concepts and goals in intercultural communication. De Gruyter Mouton.

Bennett, M. (1997). How not to be a fluent fool: Understanding the cultural dimension of language. In A. E. Fantini & J. C. Richards (Eds.), New ways in teaching culture, new ways in TESOL series II: Innovation classroom technique (pp. 16-21). TESOL.

Bennett, J. M., Bennett, M. J., & Allen, W. (2003). Developing intercultural competence in the language classroom. In D. L. Lange, & R. M. Paige (Eds.), Culture as the core: Perspectives on culture in second language learning (pp. 237-270). Information Age Publishing.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (2nd ed., pp. 21–71). Intercultural Press.

Bennett, M. J. (Ed.). (1998a). Basic concepts of intercultural communication: A reader. Intercultural.

Bennett, M. J. (1998b). Intercultural communication: A current perspective. In M. J. Bennett (Ed.), Basic concepts of intercultural communication: A reader (pp. 1– 34). Intercultural Press.

Brooker, A., Brooker, S., & Lawrence, J. (2017). First year students’ perceptions of their difficulties. Student Success, 8(1), 49-62. http://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v8l1.352

Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47–60. http://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

Chen, G.-M., & Starosta, W. J. (1998). A review of the concept of intercultural awareness. Human Communication, 2, 27-54.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2009). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Chi, D. N., & Vu, N. T. (2022). The transformation of position and teaching practices of Vietnamese EFL teachers through participation in postgraduate TESOL programs overseas. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 19(2), 718-725. http://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2022.19.2.25.718

Chi, D. N., & Vu, N. T. (2023). The development of cultural capital through English education and its contribution to graduate employability. In L. H. N. Tran, L. T. Tran, & M. T. Ngo (Eds.), English language education for graduate employability in Vietnam (pp. 141-164). Springer.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Crozet, C., Liddicoat, A., & Lo Bianco, J. (1999). Intercultural competence: From language policy to language education. In J. Lo Bianco, A. Liddicoat, & C. Crozet (Eds.), Striving for the third place: Intercultural competence through language education (pp. 1–20). Language Australia.

Deardorff, D. (2009). Synthesizing conceptualizations of intercultural competence: A summary and emerging themes. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 264–270). Sage.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in L2 motivation research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 43–59.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000034

Dunn, O. J. (1964). Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics, 6(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00401706.1964.10490181

Fantini, A. E. (2005). Assessing intercultural competence: A research project of the federation EIL. SIT Occasional Papers Seri.

Fitzgerald, H. (1999). Adult ESL: What culture do we teach? In J. Lo Bianco, A. Liddicoat, & C. Crozet (Eds.), Striving for the third place: Intercultural competence through language education (pp. 127–142). Language Australia.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Gardiner, H.W., & Kosmitzki, C. (2010). Lives across cultures. (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

Ha, N.T.T.., Ha, N.T.., & Huong, T. M. (2016). Closing the gender gap in the field of economics in Vietnam. Business and Economics Journal, 7(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4172/2151-6219.1000220

Hammer, M. R., Bennett, M. J., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory.International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 421-443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(03)00032-4

Hismanoglu, M. (2011). An investigation of ELT students’ intercultural communicative competence in relation to linguistic proficiency, overseas experience and formal instruction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 805-817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.09.001

Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: The influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020114231387

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269-293). Penguin Books.

Pham, T. N. (2014). Foreign language policies. In L. T. Tran, S. Marginson, H. Do, T. Le, N. Nguyen, T. Vu, T. Pham, & H. Nguyen (Eds.), Higher education in Vietnam: Flexibility, mobility and practicality in the global knowledge economy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 819–860). Sage.

Jæger, K. (2001). The intercultural speaker and present-day requirements regarding linguistic and cultural competence. Sprogforum, 19, 52-56.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford University Press.

Krause, K.-L., & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first-year university. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930701698892

Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. Journal of College Student Development, 50(6), 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0099

Lázár, I. (2015). EFL learners' intercultural competence development in an international web collaboration project. The Language Learning Journal, 43(2), 208-221. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.869941

Liddicoat, A. J. (2015). Multilingualism research in Anglophone contexts as a discursive construction of multilingual practice. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 11(1), 9-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1086361

Mai, H. T. N. (2018). Fostering learners’ intercultural communicative competence through EIL teaching: A quantitative study. Journal of English as an International Language, 13(2.2), 133-164. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1247022

Marek, K. (2009). Learning to teach online: Creating a culture of support for faculty. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 50(4), 275–292. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40732589

Mighani, M. G., Yazdanimoghadddam, M., & Mohseni, A. (2020). Interculturalizating English language teaching: An attempt to build up intercultural communicative competence in English majors through an intercultural course. Journal of Modern Research in English Language Studies, 7(2), 77-100. https://www.magiran.com/paper/2111249?lang=en

Moeller, A. K., & Nugent, K. (2014). Building intercultural competence in the language classroom. In S. Dhonau (Ed.), Unlock the gateway to communication. Central states Conference Report (pp. 1-18). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1160&context=teachlearnfacpub

National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project (NSFLEP). (2006). National standards for foreign language learning: Preparing for the 21st century. Allen Press.

Nieto, C. P. (2008). Cultural competence and its influence on the teaching and learning of international students [Master’s thesis], Bowling Green State University. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=bgsu1209753315

Özdemir, E. (2017). Promoting EFL learners’ intercultural communication effectiveness: A focus on Facebook. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(6), 510-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1325907

Pham, L., & Saltmarsh, D. (2013). International students’ identities in a globalized world: Narratives from Vietnam. Journal of Research in International Education, 12(2), 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240913481171

Shuck, B., & Wollard, K. (2010). Employee engagement and HRD: A seminal review of the foundations. Human Resource Development Review, 9(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309353560

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.). The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2-52). Sage.

Sinicrope, C., Norris, J., & Watanabe, Y. (2012). Understanding and assessing intercultural competence: A summary of theory, research, and practice. Second Language Studies, 26(1), 1-58. https://www.hawaii.edu/sls/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Norris.pdf

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2-52). Thousand Sage.

Sullivan, A. (2003). The British case. In G. Ballarino, W. Bien, P. Bischoff, S.-Y. Cheung, & J. O. Jonsson (Eds.). Innovation, flexibility, training and education: Link with the family situation. EU Commission.

Tesoriero, F. (2006). Personal growth towards intercultural competence through an international field education program. Australian Social Work, 59(2), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070600651853

Tirnaz, S., & Narafshan, M. H. (2018). Promoting intercultural sensitivity and classroom climate in EFL classrooms: The use of intercultural TV advertisements. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.10.001

Tran, T. Q., & Duong, T. M. (2018). The effectiveness of the intercultural language communicative teaching model for EFL learners. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0048-0

Tran, T. T. Q., Admiraal, W., & Saab, N. (2019). Effects of critical incident tasks on the intercultural competence of English non-majors. Intercultural Education, 30(6), 618-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2019.1664728

Tran, L. H. N., Tran, L. T., & Ngo, M. T. (2024). English language education for graduate employability in Vietnam. Springer Nature.

Tran, L. H. N., & Vu, N. T. (2023). The emergence of English language education in non-English speaking Asian countries. In L. H. N. Tran, L. T. Tran, & M. T. Ngo (Eds.), English language education for graduate employability in Vietnam (pp. 25-48). Springer.

Truong, L. B., & Tran, L. T. (2014). Students’ intercultural development through language learning in Vietnamese tertiary education: A case study on the use of film as an innovative approach. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(2), 207-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2013.849717

Vescio, T. K., Sechrist, G. B., & Paolucci, M. P. (2003). Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: The mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.163

Viberg, O., Hatakka, M., Balter, O., & Mavroudi, A. (2018). The current landscape of learning analytics in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior 89, 98-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.027

Vu, N. T. (2022). How differently do Vietnamese learners of English perceive their intercultural sensitivity capabilities? Intercultural Education, 33(6), 639-646. http://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2022.2154953

Vu, N. T., & Dinh, H. (2021). College-level students’ development of intercultural communicative competence: A quantitative study in Vietnam. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 51(2), 208-227. http://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2021.1893207

Vu, N. T., & Tran, T. T. L. (2023). “Why do TED talks matter?” A pedagogical intervention to develop students’ intercultural communicative competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 52(3), 314-333. http://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2022.2162950

Vuksanovic, J. (2018). ESL learners’ intercultural competence, L2 attitudes and WEB 2.0 use in American culture. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 46. https://immi.se/oldwebsite/nr46/vuksanovic.html

Weiner, G. (2006). Uniquely similar or similarly unique? Education and development of teachers in Europe. Teaching Education, 13(2), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047621022000023262

Woodfield, R., Jessop, D., & McMillan, L. (2007). Gender differences in undergraduate attendance rates. Studies in Higher Education,31(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340127

Zhou, Y. (2011). A study of Chinese university EFL teachers and their intercultural competence teaching [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Windsor.