Introduction

English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) has become a medium of communication among people of dissimilar cultural and linguistic backgrounds and first languages (Boonsuk & Ambele, 2021). Students in second (ESL) and foreign language (EFL) contexts, therefore, are encouraged to learn and improve their English proficiency to communicate with other people from different countries (Seargeant, 2012). However, there has been an ongoing debate about why EFL learners cannot speak English fluently despite the long period of schooling (Liu & Jackson, 2008; Manurung & Izar, 2019; Noom-Ura, 2013; Panthito, 2018; Sha'ar & Boonsuk, 2021). The speaking process looks easy, but in reality, it is not; it requires sufficient vocaulary, practical knowledge of sentence structure, confidence, courage, and phonological awareness of how to pronounce the words correctly (Hao, 2017). Therefore, learners with low linguistic competence often hesitate to speak, lack confidence, take longer time to compose utterances, and avoid any interaction with others as they fear making mistakes.

Like other EFL contexts, Thai EFL learners study English at school and university levels for many years, but they still hesitate and prefer remaining silent due to some internal discouraging factors. In the Thai context, the university officials and lecturers are cooperatively working to improve Thai students’ English proficiency in order to meet the national and regional demands, as Thailand joined the Asean Economic Community (AEC) and agreed to use English as a medium of communication. However, students avoid initiating an English conversation or using the language inside or outside the class. This undermines the development of their language skills and confidence to speak English in the class or in real life situations. Moreover, motivation and demotivation are important issues which need to be taken into account, particularly in language education, as they play essential roles in the students’ learning process and educational achievement.

Speaking skill as a productive macro skill refers to the "ability to share information fluently and accurately including the ability to choose appropriate vocabulary and structures in all contexts" (Nanthaboot, 2014, p. 11). Fluency is the natural use or “the maximally effective operation of the language system far acquired by the students” (Brumfit, 1984, p. 56). Demotivation is one of the persistent factors which negatively affect the language learners’ attitudes, speaking performance, and learning outcomes (Çankaya, 2018; Hayikaleng et al., 2016; Imsa-ard, 2020; Liu & Jackson, 2008; Ly, 2021; Sha'ar & Boonsuk, 2021). It refers to the "factors that reduce or diminish the motivational basis of a behavioral intention or ongoing action" (Dörnyei, 2001, p. 34). However, the debate in the Thai context about whether demotivation of the Thai EFL learners to speak English is caused by internal or external factors has not yet been empirically addressed. The researchers were inspired to conduct this study as no empirical study to date had conclusively sorted it out.

As English has become a Lingua Franca, the Thai EFL learners are required to graduate with an adequate English proficiency of B1 in the Common European Reference of Languages (CEFR) with the ability to describe their dreams, ambitions, and give reasons for opinions and plans. However, the non-major Thai Students at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University graduate with little or no basic English skills. As the Thai EFL context is devoid of previous studies that have specifically explored the internal demotivating factors of students speaking skills, the first and foremost importance of the study is to find out these factors that discourage the students to use the language inside or outside the classroom. Investigating these demotivating factors is crucial as they will have a detrimental impact on the students’ learning outcomes. The results of the study will contribute to a profound understanding of the demotivating factors that some teachers may not realize through their traditional teaching approaches. Therefore, the students' voices and perspectives on what discourages them to use the language must be taken into account because they are the ones who are learning and expected to use English inside and outside the classroom. This study specifically attempts to answer the following research questions:

1. Why are the Thai EFL learners at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University unable to speak English fluently?

2. What are the internal factors that demotivate these learners from using English in class or in daily life situations?

Literature Review

The challenges of developing speaking skills among the Thai EFL learners

The Thai EFL context is not dissimilar to other EFL contexts in which unsatisfactory outcomes of English language learning are ascribed to factors like the teacher, the student, or the learning environment (Khamkhong, 2017). According to Noom-ura (2013), one of the reasons for the failure of English-language teaching and learning in the Thai EFL context is the unqualified and poorly-trained teachers. In her study, she found some other underlying factors such as large classrooms, impractical curricula and limited access to instructional technology. These findings were confirmed by Panthito (2018) who also found that students' inability to speak English was due to the teachers' overuse of their first language, which reduces the students' confidence and eliminates opportunities to practice and improve their pronunciation. Besides, Charles et al. (2016) similarly found that teachers' negative or overuse of corrective feedback negatively affected the development of the students’ speaking skills and reduces their willingness to engage or participate in classroom activities. The teacher-centered approach to instruction is another problem that discourages students from using the language (Yuh & Kaewurai, 2021).

The issue of the students’ inability to speak English could be attributed to the students themselves. They avoid speaking English in the classrooms due to their limited grammar knowledge or fear of making grammatical mistakes which usually bring about either classmates' laughter or teacher's corrective feedback (Deveney, 2005), who found that the Thai students preferred implicit feedback, which helps them enhance their self-confidence. However, Ambele and Boonsuk (2021) found that the Thai EFL learners have negative self-evaluation as they always think that their pronunciation is not like native speakers. They further found that pronunciation among Thai EFL learners was not only a sign of one's personal ability but also a symbol of one's social class" (p. 87). Therefore, many students prefer to remain silent rather than lose face (Sha'ar & Boonsuk, 2021).

Thai EFL learners' speaking skills are critically challenged by the learning environment, with issues like class size, short English classes, lack of language labs and a traditional classroom layout (Khamkhong, 2017, Sha’ar et al, 2022). According to Noom-ura (2013), large classes with mixed abilities affect the students' exposure to the language. It creates a gap that the teachers fail to bridge. To improve the Thai students’ English skills, Noom-ura further suggested that there must be remedial English courses and suitable teaching methods that help to bridge the learning gap as many students received insufficient English learning in high school.

Internal demotivating factors of the students speaking skills

Motivation is manifested through desire, efforts, and positive attitudes towards language learning. Prinzi (2007) posited that there is a strong relationship between motivation and second language learning. She argued that without motivation students lose valuable learning experience and limit their success. Unlike motivation, which has been explored by different theoretical and empirical studies in different contexts, demotivation and demotivating factors have received little attention from scholars. Speaking demotivation likewise has been completely or partly ignored by educators and therefore, there is a lack of clear definition and theoretical foundation for speaking demotivation. However, demotivation refers to the decrease of motivation in learning due to some internal or external demotives (Dörnyei, 2001). Demotives are discouraging factors that de-energize the students’ action and/or interests (Soureshjani & Riahipour, 2012). A demotivated learner is an individual who has lost interest in learning due to factors which consequently affect the learning process and educational achievements (Çankaya, 2018; Dörnyei, 2001).

Literature conclusively indicates that internal demotivating factors, including fear, lack of confidence, attitudes, and unpleasant past experience, discourage the learners to speak English in many EFL contexts (Basa et al., 2018; Ly, 2021). Manurung & Izar (2019) found that their Indonesian EFL learners were demotivated to speak English by internal factors including lack of vocabulary, fear of making mistakes, and hesitation. They also realized that the students' fear was a persistent demotivating factor that included different issues such as the fear of making mistakes, fear of teachers' unsupportive feedback, and fear of their peers' reaction and laughter. Liu and Jackson, (2008) found that the students' fear of making mistakes increased their anxiety and reduced their motivation to communicate with others. This fear was related to teachers' feedback. In a similar context, Abrar et al. (2018) found that the Indonesian students were demotivated to speak English due to the teachers' direct and corrective feedback, which negatively affected the conversational flow and increased the students' demotivation and anxiety. Therefore, Songsiri (2007) suggested that the teachers should overlook little mistakes to boost the students' willingness to engage in the class activities. Moreover, Akkakoson, (2016) found that classmates' reaction is one of the demotivating factors which sometimes may turn into frustration and apprehension. Students avoid speaking as it makes them funny in peers' views.

Classmates' reactions also undermine the students' confidence and demotivates them. In many EFL contexts, language students tend to avoid participating in class activities or initiating any conversation with others due to their lack of confidence (Songsiri, 2007). Somdee and Suppasetseree (2013) found that the EFL learners' loss of confidence could also be caused by the negative self-evaluation of language ability and the fear of losing face, particularly when studying with students from other majors. They suggested that teachers should incorporate teaching activities that would improve the students’ confidence and motivation. In addition, students' lack of confidence is also triggered by "lacking enough time or knowledge" (Grubbs et al., 2009, p. 287). In their study about the Thai students’ speaking confidence Waluyo and Rofiah, (2021) found that the students' confidence can be negatively affected by teachers' unsupportive and demotivating feedback. Moreover, Songsiri (2007,2014) found that EFL learners' lack of confidence is caused by getting insufficient encouragement from the teacher.

Upon examining the internal demotivating factors, previous studies in the Thai EFL context (Jindathai, 2015; Sahatsathatsana, 2017; Sha'ar & Boonsuk, 2021) agree that Thai EFL learners are discouraged to speak English by some general internal factors (e.g., anxiety, fear, lack of confidence, etc.) related to the students themselves and other external factors (teachers; feedback, lack of exposure, etc.) related to the environment in which they are studying. According to, Noom-uUra (2013) the Thai students spend 12 years studying English in primary and secondary schools and four or five years more at tertiary level, but the outcome is questionable. This is often attributed to the students' lack of motivation to use the language in large classrooms with students of mixed abilities. The students' demotivation is usually ascribed to the students’ anxiety, stress, negative self-evaluation, fear of teachers' unsupportive feedback, and lack of vocabulary (Akkakoson, 2016; Jindathai, 2015). Others ascribed the issues of the Thai students speaking skills to shyness, fear of making mistakes, negative attitudes (Khamkhong (2017), the fear of 'losing face, the overuse of the Thai language in English classes, the fear of making mistakes, and the lack of enough vocabulary ( Jindathai, 2015; Sha'ar & Boonsuk, 2021).

Attitudes towards English play an essential role in students' learning and motivation. If students have negative attitudes towards the language, they will not be motivated to speak and use the language. Leong & Ahmadi (2017) assert that "without positive attitudes towards speaking performance, the aim of speaking will not be obtainable for learners" (p. 38). Dincer & Yesilyurt (2013) attributed students' attitudes towards speaking English on the one hand to teachers' teaching methods, and on the other hand to students’ aspiration for a future career. Regarding this particular finding, Ahmad (2015) found out that students who want to study abroad, become teachers, or even waiters need English to express themselves and communicate with others. Moreover, some other students develop negative attitudes towards speaking English because it seems difficult and unnecessary for their lives (Hayikaleng et al., 2016).

Another internal demotivating factor is the student's past experience. The learner's journey of success or failure in language learning is always accompanied by different attitudes and emotions (Imsa-ard, 2020). Therefore, teachers should build a positive relationship with the students and prepare a comfortable atmosphere in the classroom to improve the students’ motivation, attitude, and alter their negative past experiences (Imsa-ard, 2020). Ahmed (2015), in the same way, emphasized language learners’ previous experience: “if they were successful, then they may be pre-disposed to success now. Failure then may mean that they expect failure now" (p. 6). Therefore, students' negative past experiences often discourage them from using the language either in educational or real-life settings. Negative past experiences were possibly caused by personal constructs such as anxiety, fear of risk-taking, and inhibition (Leong & Ahmadi, 2017). However, White (2019) ascribes students’ dispiriting past experience in the Thai context to the teachers and their teaching strategies. He explains that the problem is rooted in the past; teachers may lack adequate English skills and thus revert to overuse of students L1, while teaching basic vocabulary and grammar structure. As a result, many students are unable to communicate or even form a meaningful sentence. Besides, negative past experiences towards speaking English can be caused by the teachers' negative evaluation, (Gömleksiz, 2010). Leong & Ahmadi (2017) suggest that "if learners are always corrected, they will be demotivated and afraid of talking" (p. 37). To sum up, EFL learners often feel demotivated to speak English due to the lack of confidence, lack of vocabulary, hesitation, negative attitudes towards English, fear of making mistakes, and serious concern about teachers’ feedback and peers’ reaction.

Methods

Research design

The study employed a mixed-methods design, i.e., the combination of both qualitative and quantitative methods in a single study (Hesse-Biber, 2010), to find out why the Thai EFL learners at NSTRU cannot speak English and what are the internal factors that demotivate them from speaking English.

Participants

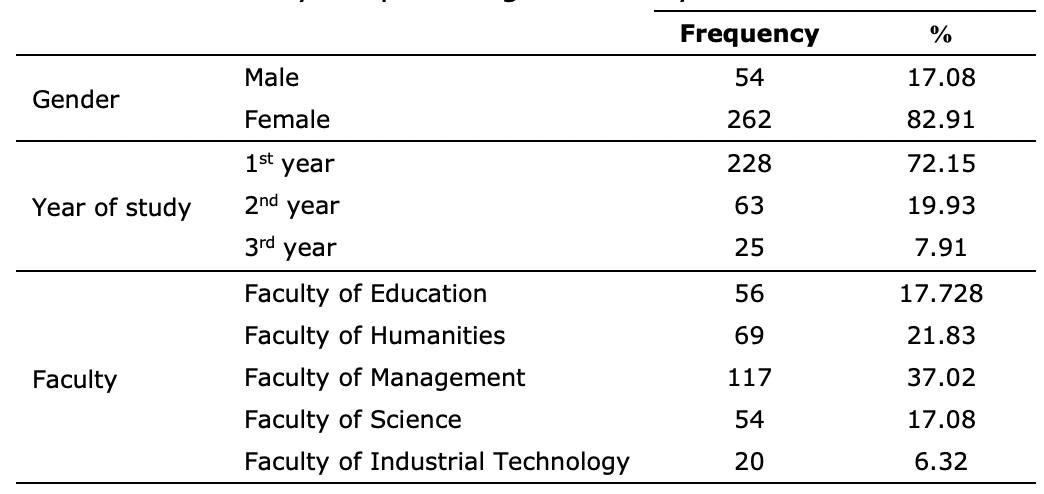

A total of 316 students from five faculties who studied General English courses (GE) were randomly selected to take part in the study. Simple random sampling helped to make statistical inferences about the population and ensured high internal validity. It reduced the impact of potential confounding variables (Indrayan & Holt, 2016). The sample size was determined by Krejcie and Morgan's (1970) formula. Table 1 gives some basic demographic information about the participants.

For a semi-structured interview, ten participants were conveniently selected, two representatives from each faculty to provide a full picture of the research context. These GE students were selected as a subject for the study as they usually have low English proficiency and graduate with limited ability to speak English fluently.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics

The researchers obtained informed consent and official oral permission from the five faculty deans to collect data from the students in different programs because this research is conducted based on the actual persistent problems known by the university members. Moreover, the deans cooperated with researchers by asking lecturers to share a link to the questionnaire (Appendix 1) with their students. In the survey (Appendix 1), the researchers explained to the students the purpose of the study, the nature of their optional participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. During the data collection, the students had the right to fill out the survey or stop to continue at any point. The researchers could not obtain individual informed consent from each student due to the large number of participants and the limited resources.

Instruments

A questionnaire and semi-structured interview were employed to collect the data. Data was collected through online platforms and tools due to social distancing measures and working from home policy.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire with a five-point Likert Scale was utilized to collect the data. Likert scale was used as it allowed several issues related to the students’ speaking skills to be addressed sequentially and in a relatively short time frame (Lynch et al., 2009). The questionnaire was divided into two parts (RQ1 and RQ2) with 4 steps. First, some questionnaire statements were adapted from Khamprated (2012); Pandito (2018), and some others were developed by means of conducting informal interviews and discussions in a regular activity called 'Let's Talk English with Foreign Teacher,' and some questions arose from the researchers’ past observations while teaching GE courses. Second, the questionnaire statements were translated into Thai to help the participants to understand the meaning of each item correctly. Third, the questionnaire was piloted with non-target participants, and Cronbach's alpha was utilized to examine the reliability and internal consistency of the items. The value for Cronbach’s Alpha for the survey was 0.966 which indicated a high internal consistency (See Appendix 2). Items below 0.70 were excluded from data analysis to improve the overall accuracy and trustworthiness of the findings (Rofiah et al., 2021). Cronbach's Alpha values usually range between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating higher internal consistency and reliability. A higher alpha value shows that the items are strongly related to each other and that the scale is more dependable for measuring the idea or the concept it intends to assess (Taber, 2018). Fourth, the questionnaire was formatted in Google form and the link was shared with the target participants.

Semi-structured interview

A semi-structured interview helped to elicit students’ responses about the factors that demotivate them from speaking English. It gave the participants a chance to disclose the most important factors that discouraged them from speaking English. It also enabled the researchers to obtain richer information (Padgett, 2011).

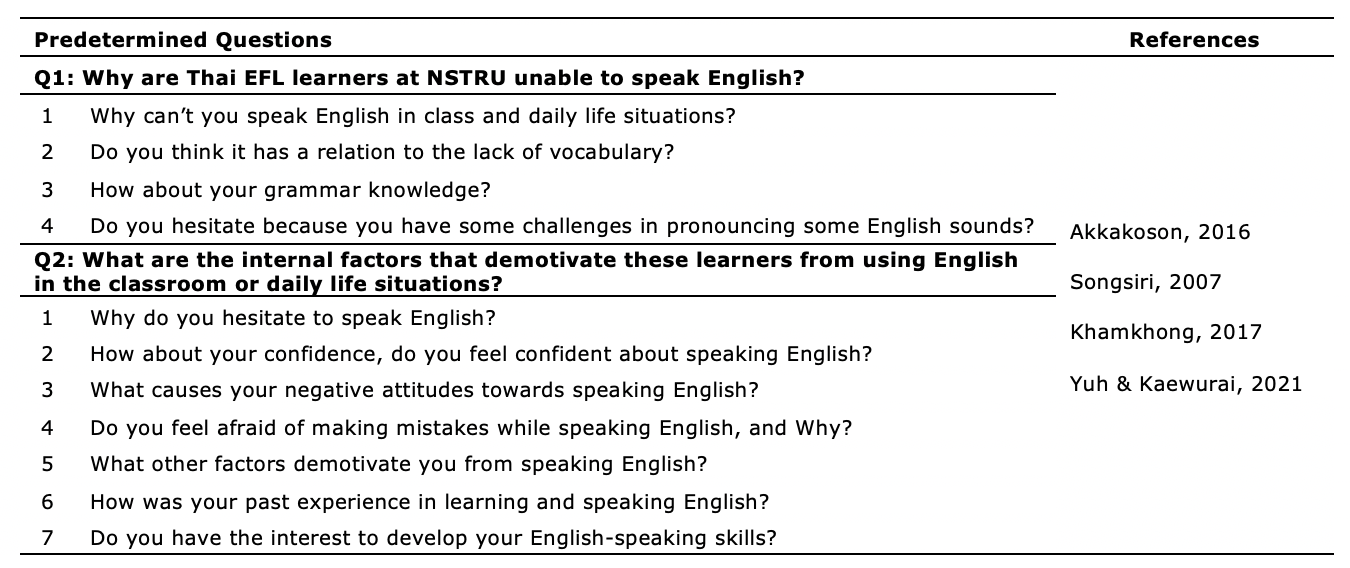

Table 2: Examples of semi structured-interview pre-determined questions

Data collection

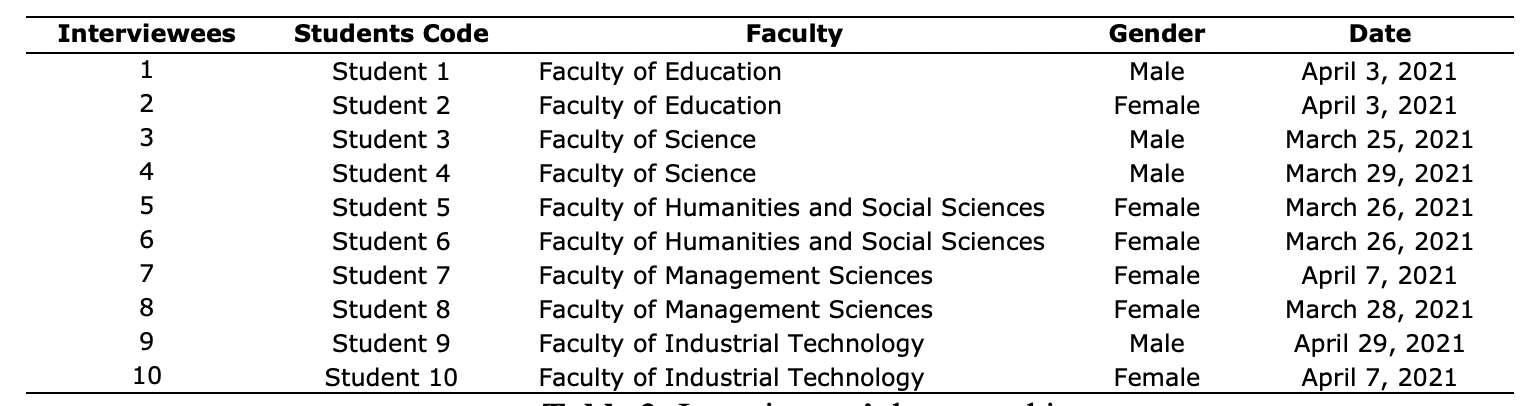

The quantitative data was collected from March 25 to April 7, 2021, (Table 3) at NSTRU, Thailand. The questionnaire was distributed to the participants using Google Forms. The researchers sent the link and/or the QR code through LINE[1] or Facebook and received 354 responses. After screening the data, 316 questionnaires were considered for further analysis, and 38 were removed because they were incomplete. Qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews with ten students; two representatives from each faculty. The researchers included a statement at the end of the questionnaire asking if the respondent would be willing to participate in an interview. More than 25 students showed their interest, but the researchers selected only ten as the number of volunteers did not represent each Faculty equally. The interviews were conducted via Google Meet due to the pandemic and the restrictions of social distancing. The interviews were scheduled for ten to fifteen minutes for each participant. The researchers made the appointment to have an online interview based on the participants' preferred time. Before commencing the interview, the researchers explained the purpose and procedure of the interview to the interviewees.

Table 3: Interviewees’ demographics

Data analysis

Quantitative data

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 22. The first step was computing and cleaning the collected data. Any duplicated or incomplete responses were deleted. Second, the reliability analysis was run to check the internal consistency for all items and sub-scales. Items below .70 were excluded from the data analysis. However, the results revealed that all sub-scales had high internal consistency and Cronbach alpha was at least 0.888 for all subscales. (See Table 4). Therefore, all the sub-scales and items were considered for the data analysis. Afterwards, descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used in order to answer the first and second research questions. The data had a normal distribution with the skewness and kurtosis between -2 and +2 for all items (see Appendix 3) (George & Mallery, 2010).

Qualitative data

The interview data were analyzed through qualitative content analysis, a “research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use (Krippendorff, 2004, p. 18). The data analysis procedure proposed by Hsieh & Shannon (2005) was followed: first, the interview records were transcribed by listening to and writing every word. Second, the transcripts were sent back to the interviewees to get approval and enhance the validity of the findings. Third, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reading the transcripts thoroughly again and again. Fourth, the researchers began highlighting the emerging themes while reading the transcripts. Fifth, the themes and codes were organized into categories. In this process, some sub-themes were merged, and other irrelevant codes were ignored. Sixth, the researchers picked up only some themes which contributed to answering the research questions. Finally, the qualitative findings were listed and matched with the qualitative findings.

Findings

Quantitative findings related to Research Question 1

First, this study aims to find out why the Thai EFL learners at NSTRU, cannot speak English. Speaking is a macro skill that consists of several sub-skills, i.e., vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and fluency. These sub-skills have interconnected relationships, and therefore, if a student has difficulty with any of these sub-skills, it will negatively affect their speaking ability. That is why the study began investigating these essential competencies before examining the demotivating internal factors.

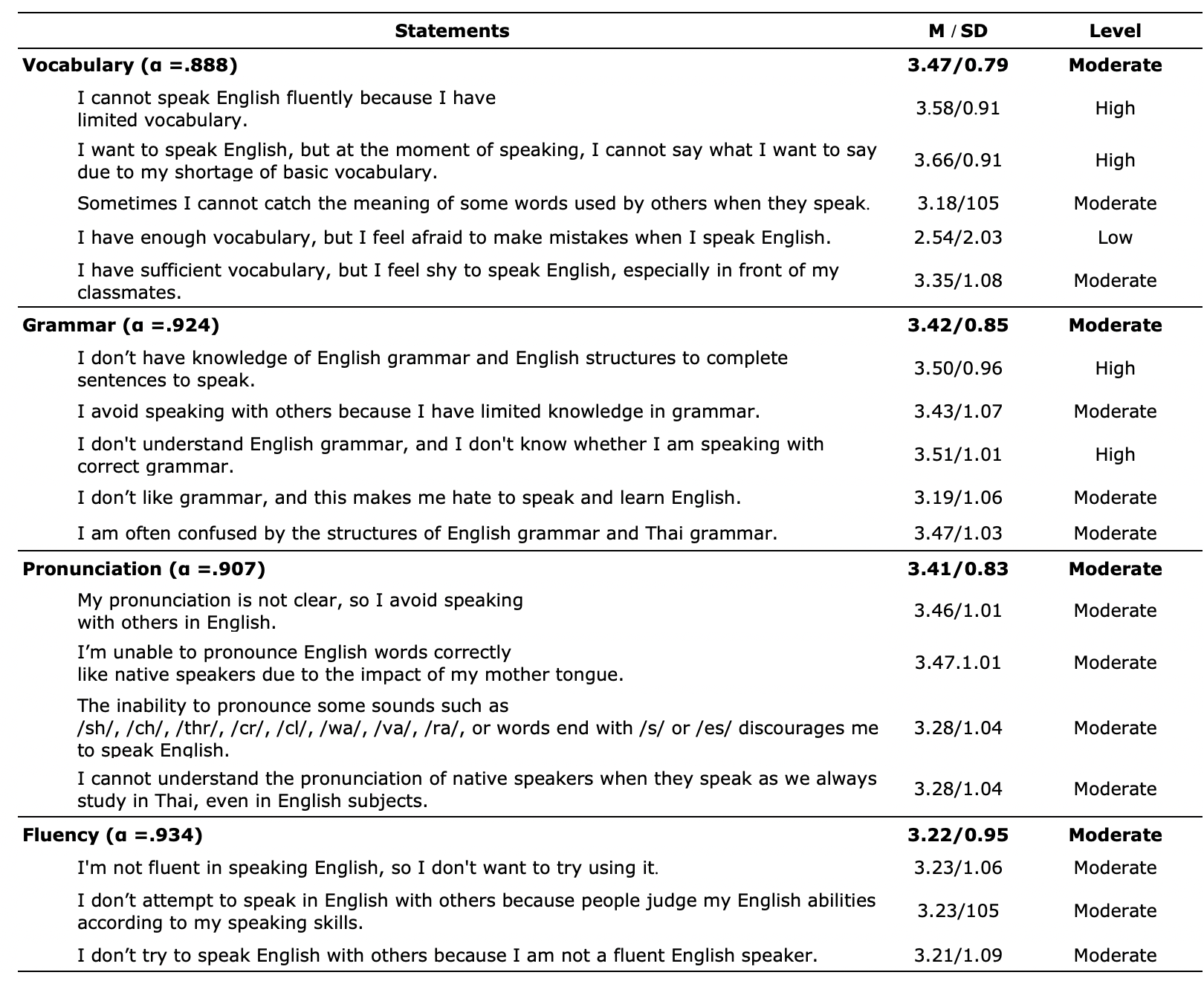

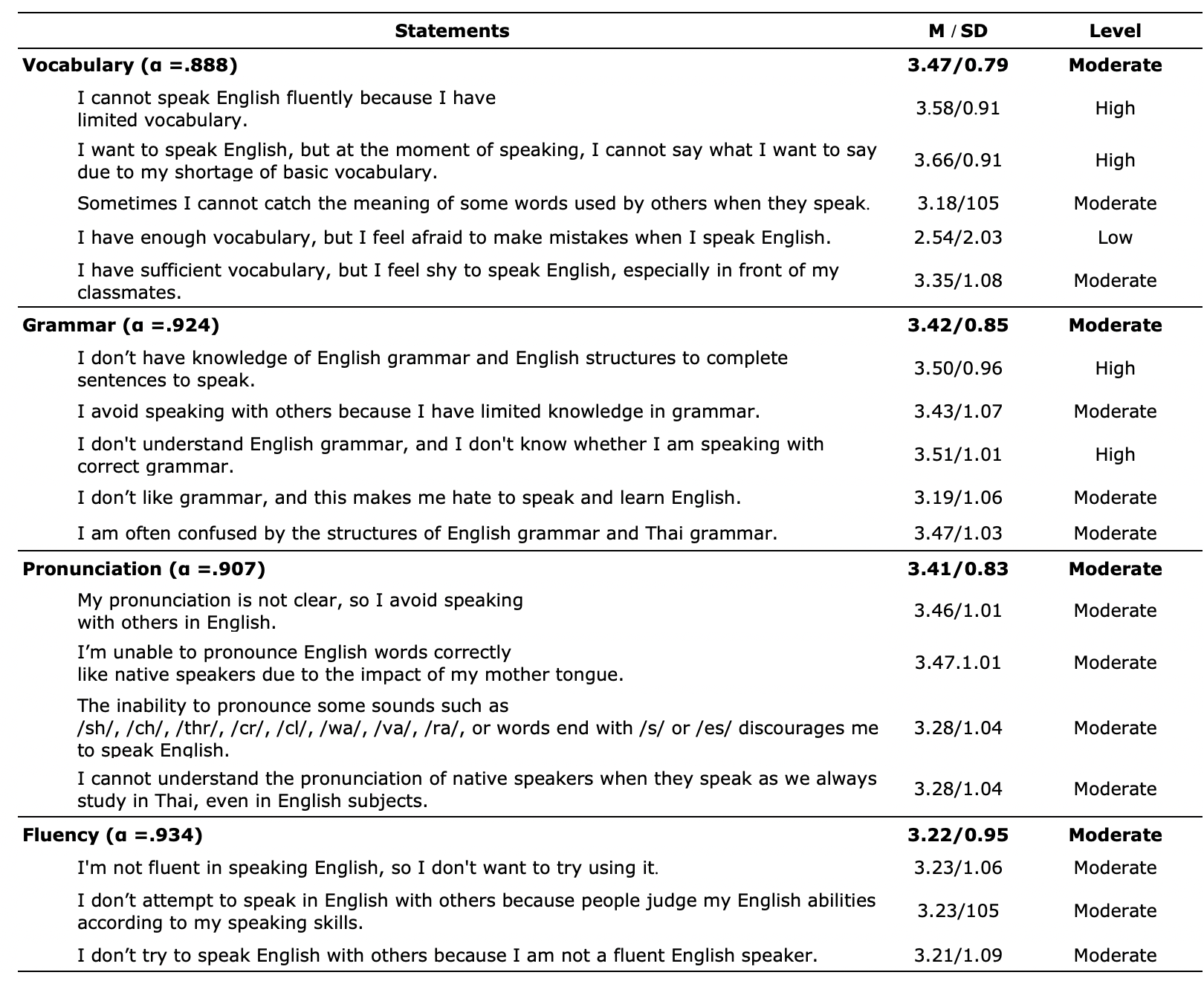

Table 4: Components of speaking skills

The data in Table 4 reveals that the students feel they cannot speak English because they do not have the basic vocabulary (x̄=3.66, SD=0.91) to initiate or engage in an English conversation. This urges them to remain silent inside and outside the class as they prefer not to experience communication breakdown. This deficiency in vocabulary (x̄=3.58, SD=0.91) made it difficult for them to catch the meaning of some words (x̄=3.18, SD=1. 05) when they were spoken by others including their teachers. This lack of vocabulary makes the students unable to speak English and, hence avoid speaking with others as they cannot express what do they want to say.

Grammar is another component of speaking skills that creates a basis for effective communication. It is essential because it helps to enhance speaking accuracy. However, the data in Table 4 reflects that the students feel they cannot speak English due to their lack of grammar knowledge (x̄=3. 50, SD=0. 96), which they can use to correctly construct accurate sentences while speaking. The students' uncertainty about the correct use of (x̄=3. 51, SD=1.01) urges them to avoid engaging with others in any English conversation (x̄=3. 43, SD=1. 07). They often get confused by the differences between English sentence structure and Thai grammar (x̄=3.47, SD=01.03) due to the dominance of their mother tongue and the limited use of English in the classroom. The lack of grammar knowledge and confusion appears to ignite students’ negative attitudes (x̄=3. 19, SD=1. 06) not only towards speaking English but also towards learning English as a whole.

Pronunciation is the third component that affects Thai EFL students’ speaking skills due to the interference of their mother tongue or the unavailability of some English sounds in their first language. The data in Table 4 indicate that the Thai EFL learners avoid speaking English due to their inherent belief in having unclear pronunciation (x̄=3. 46, SD=1. 01). The unavailability of some English sounds e.g., /sh/, /ch/, /thr/, /cr/, /cl/, /wa/, /va/, /ra/, or words ending with /s/ or /es/ in Thai language (x̄=3.28, SD=1.04) creates a challenge, and many respondents believe that their pronunciation is dissimilar to that of native speakers (x̄=3. 47, SD=1. 01). Finally, students believe that the overuse of their mother tongue even in their English classes (x̄=3. 46, SD=1. 00) undermines the chances for practicing and improving their pronunciation as the classroom is the only place that can give them chance to use the language. The overuse of their mother tongue may also increase the difficulty of understanding others due to the limited exposure.

Fluency is the fourth component of speaking skills, and it is inaccurately used to judge others’ overall English ability. The data in Table 4 indicate that the students avoid speaking English inside or outside the class because they believe their English proficiency will be judged according to their speaking ability (x̄=3.23, SD=01.05). This increases their diffidence and their hesitation to use the language. The fear of being judged for low English ability urges most of the students to stop (x̄=3.23, SD=01.05) even trying to speak English.

Qualitative findings related to Research Question 1

In their interviews, the Thai EFL learners attributed their inability to speak English to different reasons, such as their lack of vocabulary.

I don't know the vocabulary because I don't pay attention to it, I don't know how to speak each word. (Student 2)

This deficiency in vocabulary led most of the students to believe they were unable to speak and to avoid engaging in an English conversation with others. It also affected the students' ability to understand what other speakers, including their teachers, are saying.

I don't know vocabulary they said. I can't catch what they said. (Student 2)

Some words are simple, but when I listen from teachers or other speakers, I couldn't catch it. I feel it was so fast; I couldn't think, and words became incomprehensible. (Student 1)

A lack of English grammar knowledge also prevented students from speaking English. For example.

There is a little knowledge of English grammar. I cannot speak in a sentence and don't understand grammar. (Student 1)

Grammar has a lot of structure to remember, which makes it confusing. (Student 3)

There are many structures to remember. It's confusing. (Student 3)

English grammar is not the same as Thai; it is confusing and difficult. (Student 5)

Moreover, the qualitative data showed that the students were discouraged from speaking English because they could not pronounce some English sounds which are not available in the Thai language.

I can’t pronounce /sh/ or /ch/, I'll pronounce them similarly. (Student 1)

Some vocabulary tends to end with /s/. I'm afraid to pronounce it incorrectly. (Student 4)

It was also found that the students had a belief that they were not good in English and hence they did not endeavor to speak English.

I'm not fluent in English. So, I don't like speaking English at all. (Student 8)

I'm not good at English. So, I can't speak English fluently. (Student 6)

Quantitative findings related to Research Question 2

Second, the study aimed to examine the internal factors that demotivate the students’ use of the language in the classroom or daily life situations. The internal factors include fear, lack of confidence, attitudes towards English, and past experience.

Table 5: Internal demotivating factors

The data in Table 5 reveal that the students were demotivated to speak English due to their fear which was caused by fear about different issues including, the fear of making grammatical mistakes (x̄=3.49, SD=1.05), fear of teachers’ unsupportive feedback (x̄=3.41, SD=01.09), miscommunication due to the limited vocabulary (x̄=3.49, SD=1.05) and the fear of the reaction of their classmates (x̄=3.41, SD=01.08). Besides, the data indicated that the students were demotivated to speak English due to their lack of confidence which was caused by underestimating their English ability (x̄=3.35, SD=1.06). Their lack of confidence was brought about by the lack of teachers’ support and encouragement (x̄=3.37, SD=1.05).

Moreover, attitudes towards English language affect students’ motivation and skills, including speaking skills. The data in Table 5 reveal that students are demotivated to speak because of their negative attitudes towards English language, particularly speaking skills. Students indicated that they don't like speaking English (x̄=3.23, SD=01.11) because it is difficult, and they always get low scores. They had negative attitudes toward English because the subject is not interesting for study (x̄=3.00, SD=1.19), and they don't get any chance to use it with others as their L1 is dominating every aspect of their lives (x̄=3.73, SD=1.06). In addition, Thai EFL learners were demotivated to speak English due to their unpleasant past experiences with speaking the language either inside or outside the classroom. The data in Table 5 show that the students were discouraged to speak English because they had unpleasant experiences (x̄=3.10, SD=1.26) with English subjects and teachers' disengaging teaching approaches. It was found that they were demotivated because their past attempts to speak English with their classmates and foreigners (including some teachers) were not successful (x̄=3.31, SD=01.10).

Qualitative findings related to Research Question 2

The qualitative findings surprisingly indicated that the Thai EFL learners were demotivated to speak English because they feared the teachers’ unsupportive feedback. As one interviewee explained:

I'm afraid that when I pronounce it won’t be right. I used to pronounce some words wrong and that made the teacher scolded me. So, I don't like this subject at all. (Student 4)

Another classroom demotivating factor was the peers’ reaction for their speaking initiative. The students felt demotivated to speak English inside the class as they feared their classmates’ reaction and laughter.

I'm afraid my friends will laugh at me if I speak wrong English. (Student 1)

I'm afraid people who hear me when I speak English will judge me as uneducated. (Student 2)

I'm very worried because if we don't pronounce it clearly, it makes me feel embarrassed. (Student 10)

In addition, the qualitative findings suggested that the students were discouraged to use the language due to their lack of confidence. They underestimate their English ability and hence hesitate to speak among students from other majors.

I’m embarrassed when I study with other majors. I'm afraid that they will say that I have grown up and still can't speak. (Student 3)

Embarrassed by people we speak wrong; they tend to laugh at us. (Student 8)

Moreover, the qualitative findings showed that the students did not like speaking English because it was not related to their daily life.

The idea is that English is not used in everyday life and class; teachers rarely say it is okay or give any compliment. They always remain silent whether we speak good or not. I don't know whom to talk to. (Student 7)

When pronouncing it wrong, it makes me feel embarrassed. (Student 2)

The qualitative data unexpectedly revealed that the students have negative attitudes towards English as they did not like it and thought it was not useful for them in the future.

I don't pay much attention to English because I don't like it. (Student 8)

I feel that it is so difficult that I do not want to study. I do not even try to memorize English words or grammar rules. We don't use English to communicate with others, so think it is not needed for me. (Student 10)

The qualitative findings also showed that the Thai EFL learners were demotivated by their unsuccessful past experiences.

I have been studying English since high school, but still, I am still in the same level. I cannot say what I want to say. Many difficulties in vocabulary, grammar, accent, and others. I realize however I try, the result will be the same. Most of the teachers don’t understand the students’ good way to learn. (Student 9)

Discussion

The study investigated the perspective of Thai EFL learners at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University (NSTRU) as to why they cannot speak English. It also examined the internal factors that demotivate students from using the language either in class or in daily life situations. The findings revealed that the students believe they cannot speak English due to difficulties in all the components of the speaking skills. It was also found out that they were demotivated to speak English due to internal factors including: fear, lack of confidence, negative attitudes towards learning English, and past experience.

Research question 1: Why are the Thai EFL learners at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University unable to speak English fluently?

The findings indicate that the Thai EFL learners were unable to speak English due to their limited vocabulary, which consequently made it difficult for them to catch the meaning of words used by others, including their English teachers. This shortage of vocabulary makes them unable to express what they want to say clearly. In the same Thai EFL context, Akkakoson (2016) found out that the students’ lack of vocabulary demotivates them to speak the target language as it often leads to a breakdown in conversation. This finding will serve as a reminder for the teachers that the students in the EFL contexts need to enrich their vocabulary and use it through well-designed and purposeful activities due to the limited chances to use the language in their real-life situations. Second, it appears that the Thai EFL learners avoided speaking English due to their poor grammar knowledge. They avoided participating in class activities due to their confusion and uncertainty of usage while speaking. This confusion was caused by the limited exposure to the language (one subject per semester) and the dominance of the Thai language in the Thai EFL context (using English is limited to the classroom environment). The students got rare chances to use and improve their language skills and areas including grammar. This corroborates the findings in Deveney (2005) which revealed that the students preferred to remain silent instead of receiving overly correcting or unsupportive feedback from the teacher or being laughed at by their peers. This gives the teachers an insight on how to enhance the students’ grammar knowledge through planned outdoor activities like ‘Let’s Talk English with Teachers’ that increase the students’ exposure. Third, the Thai learners refrained from speaking English as they strongly believed that their pronunciation was unintelligible, i.e., dissimilar to that of a native speaker. Exploring this issue further, the unavailability of some English sounds in Thai language e.g., /sh/, /ch/, /thr/, /cr/, /cl/, /wa/, /va/, /ra/, or final position sounds like /s/ or /es/ made their pronunciation different but understandable. Therefore, the Thai EFL learners should not feel inferior in their pronunciation and accent as their English is one of the legitimate varieties of world Englishes known as Tinglish (Ambele & Boonsuk, 2021). The study findings will make the teachers aware of the students’ concern about their pronunciation and serve as a guide to improve the students’ ability to produce the sounds unavailable in their mother tongue through some techniques like imitation or listen and repeat. Fourth, it was found out that the Thai EFL learners preferred not to speak English as they thought they were not fluent enough and their level of English would be judged by their speaking ability. The Thai students specifically at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University normally used to be mixed with other students from different majors and therefore, prefer to remain silent instead of being laughed at or corrected by the teacher in front of other students. This finding is not in line with Panthito (2018) who attributed the students' inability to speak fluently to the overuse of L1 by Thai teachers, which thus reduced students' confidence and chance to practice the language. It also contradicts with Noom-ura (2013), who ascribed the students’ inability to speak English to other challenges, including the lack of exposure, shyness to speak English with classmates or others, and lack of motivation and sense of responsibility for their learning. To improve the students’ speaking skills, the teachers should encourage the students with supportive feedback and avoid corrective feedback which critically discourages their initiative.

Research question 2: What are the internal factors that demotivate these learners from using English in class or in daily life situations?

The students were discouraged to speak English due to their fear, which entangled different issues, including the fear of making mistakes. This finding is in line with Manurung and Izar (2019), who found that the students were reluctant to speak English due to their fear of grammatical or pronunciation mistakes. This kind of fear increases the students' anxiety and reduces their motivation to use the language as they do not want to be seen as imperfect by their peers (Liu & Jackson, 2008). The students in this study also feared teachers' feedback. Negative feedback had discouraged the students’ initiative and negatively affected the students’ and teachers’ relationship. This accords with Abrar et al. (2018), who noticed that the teachers' direct corrective feedback affects the communication flow and increases the students' demotivation and anxiety. Another cause of students' fear was their classmates' reactions. The students avoided speaking English inside the class due to their classmates' reaction, which sometimes leads to frustration and apprehension (Akkakoson, 2016). These findings could increase teachers’ awareness of students’ fears. This will help them to find pedagogical strategies (e.g., ignoring minor mistakes, using script first and peer work) that enhance the students’ courage to use the language.

Another demotivating factor was the students' lack of confidence. The findings showed that the students felt discouraged to speak English due to their low English proficiency. This lack of confidence can be attributed to their limited knowledge and exposure, especially in the Thai EFL context in which students prefer to listen rather than to speak (Grubbs et al., 2009). In our context, the students’ lack of confidence is heightened by the classroom environment in which students in GE classrooms are mixed with other students from different majors with no concern about their English level or the challenges that may affect their learning. This makes them shy to speak and prompts them to avoid participating in the classroom activities. This finding accords with Somdee and Suppasetseree (2013) who ascribed the students' loss of confidence to their fear of making mistakes and losing face in front of students from other groups. In addition, it was found that the students lost their motivation to speak English due to the teachers' insufficient encouragement. Students were demotivated and disengaged by teachers’ use of traditional teaching methods and approaches. To enhance the students’ confidence and participation in speaking activities, the teachers should employ cooperative teaching strategies such as communicative and students-center approaches to improve the students’ confidence and participation in speaking activities (Songsiri, 2007).

The findings also showed that the students were discouraged to speak English due to their negative attitudes towards English as a subject of study. This could be ascribed to the teachers' teaching method, which Li & Zhou (2017) found as a demotivating factor. Their findings demonstrated that the students were dissuaded by the teachers' unclear teaching and use of sarcastic language in class. Besides, the findings of this study revealed that the students were demotivated after getting low grades in English subjects. This affected their Grade Point Average (GPA) and led some students at the University to opt for Chinese or Japanese language instead. This finding is not in line with Hayikaleng et al. (2016), who related students' demotivation to their belief that English is not necessary for their lives. In addition, students in the present study were demotivated to learn and speak English due to the lack of opportunities to use the language outside of the classroom. This finding is supported by Noom-ura (2013), who found out that the Thai EFL learners wish to speak English fluently, but they have several challenges, including the lack of exposure. These findings could encourage the teachers to adapt modern teaching styles such as active learning and student-centered approach that effectively increase the students’ involvement and enhance their positive attitudes toward speaking English inside and outside the classroom.

The students in this study were demotivated to speak English in the classroom or in real-life situations due to their unsuccessful or unpleasant past experiences. The interviews exposed that the students had tried to speak English; however, their attempts were unsuccessful. The students did not try to speak English again, and it seems that the teacher was the cause of their demotivation particularly while not correctly supporting the students with feedback. This can be attributed to some discouraging past experiences or personal constructs such as anxiety, fear of risk-taking, and inhibition (Leong & Ahmadi, 2917). Gömleksiz (2010) contrarily ascribed past experiences to teachers' negative evaluation. This finding corroborates with White (2019), who similarly explained that the problem lies in the teachers who lack English teaching skills and, thus, resort to overuse of the Thai language and focus on grammar structures and vocabulary, which makes the students unable to speak or use the language. Nevertheless, both teachers and students have a complementary role in the learning process, and hence the discouraging past experiences might disproportionately be attributed to both of them. The study findings could serve as a guide for the teachers to reconsider their teaching approaches, styles of feedback, the students’ attitudes, and the classroom environment as these issues directly or indirectly influence the students’ learning process, motivation, and educational achievements.

Conclusion and Implications

This study aimed to 1) investigate why the Thai EFL learners at Nakhon Si Thammarat Rajabhat University (NSTRU) cannot speak English fluently and 2) examine the internal factors that negatively demotivate them from speaking English either in class or in daily life. A mixed-methods approach was used to collect and analyze the data.

To answer the first research question which attempted to find out and account for the learner’ inability to speak English fluently. The quantitative and qualitative results suggested that the learners could not speak English because they had difficulties in all four components of speaking skills: vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and fluency. The students stated that they were unable to speak English due to their limited vocabulary which made it difficult for them to express what they wanted to say clearly. Besides, they avoided speaking English due to their poor English grammar, unintelligible pronunciation, and the fear of being judged on their level of English based on their speaking ability or fluency. To answer the second research question which examined the internal factors that demotivate the learners from speaking English in class or in real-life situations, the findings revealed that this demotivation was due to four internal factors, fear, lack of confidence, negative attitudes towards speaking, and the hindrance of unpleasant past experiences.

The findings of this study can not only add new knowledge about the Thai EFL context but also provide some guidelines to reconsider the teaching process. They expose persistent factors that discourage the students from speaking English either in the classroom or in real life situations. Based on these findings, the teachers should reconsider their teaching approaches, strategies, feedback and reflect upon why the students cannot speak English and what factors they should take into account when the students hesitate to speak or avoid engaging in activities. It could also open the door for the teachers’ creativity to tackle such challenges as they may differ from one student to another.

The study has some limitations, first, it employed volunteers for the qualitative data through which there might be a selection bias. Second, while collecting the quantitative data female respondents were overrepresented. Third, we were unable to measure the demotivating internal factors in terms of grades in pre- and post-test because the students are allowed to continue joining the class even after five weeks from the starting date. Fifth, the study focused on why the students cannot speak and what the internal demotivating factors were from their perspective only. Therefore, a further study that would test some solutions for these demotivating factors from both students’ and teachers’ perspectives is recommended to better understand the implication of the findings of the present study.

References

Abrar, M., Mukminin, A., Habibi, A., Asyrafi, F., Makmur, M., & Marzulina, L. (2018). If our English isn't a language, what is it? Indonesian EFL student teachers' challenges speaking English. TQR: The Qualitative Report, 23(1), 129-145. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3013

Ahmed, S. (2015). Attitudes towards English language learning among EFL learners at UMSKAL. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(18), 6-16. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/23610/23984

Akkakoson, S. (2016). Speaking anxiety in English conversation classrooms among Thai students. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 13(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2016.13.1.4

Ambele, E. A., & Boonsuk, Y. (2021). Thai tertiary learners' attitudes towards their Thai English accent. PASAA: Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand, 61, 87-110. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1304983

Basa, I. M., Asrida, D., & Fadli, N. (2018). Contributing factors to the students’ speaking ability. Langkawi: Journal of The Association for Arabic and English, 3(2), 156-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.31332/lkw.v3i2.588

Boonsuk, Y., & Ambele, E. A. (2021). Towards integrating lingua franca in Thai EFL: Insights from Thai tertiary learners. International Journal of Instruction, 14(3), 17-38. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.1432a

Çankaya, P. (2018). Demotivation factors in foreign language learning. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Technology, 3(1), 1-17. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/208859

Charles, T., Tangkawanit, W., Ketnarongrattana, S., & Soontornwipast, K. (2016). Native English-speaking teachers’ use of corrective feedback in a Thai speaking oriented ESL context. Rangsit Journal of Educational Studies, 3(1), 48-57. https://rsujournals.rsu.ac.th/index.php/RJES/article/view/2256/1766

Deveney, B. (2005). An investigation into aspects of Thai culture and its impact on Thai students in an international school in Thailand. Journal of Research in International Education, 4(2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240905054388

Dincer, A., & Yesilyurt, S. (2013). Pre-service English teachers' beliefs on speaking skills based on motivational orientations. English Language Teaching, 6(7), 88-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n7p88

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second language motivation research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 43-59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000034

Gömleksiz, M. N. (2010). An evaluation of students’ attitudes toward English language learning in terms of several variables. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 913-918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.258

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Grubbs, S. J., Chaengploy, S., & Worawong, K. (2009). Rajabhat and traditional universities: Institutional differences in Thai students’ perceptions of English. Higher Education, 57(3), 283-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9144-2

Hao, D. T. T. (2017). Identify factors that negatively influence: Non-English major students’ speaking skills. Higher Education Research, 2(2), 35-43. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.her.20170202.12

Hayikaleng, N., Nair, S. M., & Krishnasamy, H. A. (2016). Thai students’ motivation on English reading comprehension. International Journal of Education and Research, 4(6), 477-486. http://ijern.com/journal/2016/June-2016/41.pdf

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. Guilford.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Imsa-ard, P. (2020). Motivation and attitudes towards English language learning in Thailand: A large-scale survey of secondary school students. REFLections, 27(2), 140-161. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/reflections/article/view/247153

Indrayan, A., & Holt, M. P. (2016). Concise encyclopedia of biostatistics for medical professionals. Chapman and Hall.

Jindathai, S. (2015). Factors affecting English speaking problems among engineering students at Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology. TNI Journal of Business Administration and Languages, 3(2), 26-30. https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/TNIJournalBA/article/view/164492

Khamkhong, Y. (2017). Developing English proficiency among Thai students: A case study of St. Theresa International College. Theresa International College. 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3086520

Khamprated, N. (2012). The problems with the English listening and speaking of students studying at a private vocational school in Bangkok, Thailand [Unpublished master's thesis]. Graduate School, Srinakharinwirot University. http://thesis.swu.ac.th/swuthesis/Tea_Eng_For_Lan(M.A.)/Nualsri_K.pdf

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607-610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

Leong, L. M., & Ahmadi, S. M. (2017). An analysis of factors influencing learners’ English speaking skills. International Journal of Research in English Education, 2, (1)34-41. http://ijreeonline.com/article-1-38-en.pdf

Li, C., & Zhou, T. (2017). A questionnaire-based study on Chinese University students' demotivation to learn English. English Language Teaching, 10(3), 128-135. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n3p128

Liu, M., & Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL learners' unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00687.x

Ly, K. C. (2021). Factors influencing English-majored freshmen’s speaking performance at Ho Chi Minh City University of food industry. Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, 3(6), 107-112. https://doi.org/10.32996/jeltal.2021.3.6.15

Lynch, L., Hancox, K., Happell, B., & Parker, J. (2009). Clinical supervision for nurses. Wiley.

Manurung, Y. H., & Izar, S. L. (2019,). Challenging factors affecting students’ speaking performance. In ICLLE 2019: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Language, Literature, and Education, ICLLE 2019, 22-23 August, Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia (p. 34). http://dx.doi.org/10.4108/eai.19-7-2019.2289545

Nanthaboot, P. (2014). Using communicative activities to develop English speaking ability of Matthayomsuksa three students, [unpublished Master dissertation]. Srinakharinwirot University. https://ir.swu.ac.th/jspui/handle/123456789/4083

Noom-ura, S. (2013). English-Teaching problems in Thailand and Thai teachers' professional development needs. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 139-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n11p139

Padgett, D. K. (2011). Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Sage.

Pandito, P. B. (2018). A Study of the problems of English speaking skill of the first year students at Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University [Unpublished master’s thesis], Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya University.

Panthito, B. (2018). A study of English speaking skills of first-year students in Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University. Journal of MCU Humanities Review, 4(2) 185 -195. https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/human/article/view/164535/143256

Prinzi, L. (2007). Motivation and second language learning: Implications for ASL. [Masters dissertation, Rochester Institute of Technology. RIT Scholars Works. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4992&context=theses

Rofiah, N. L., & Sha’ar, M. Y. M. A., & Waluyo, B. (2022). Digital divide and factors affecting English synchronous learning during Covid-19 in Thailand. International Journal of Instruction, 15(1), 633-652. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2022.15136a

Sahatsathatsana, S. (2017). Pronunciation problems of Thai students learning English phonetics: A case study at Kalasin University. Journal of Education, Mahasarakham University, 11(4).

Seargeant, P. (2012). Exploring world Englishes: Language in a global context. Routledge.

Sha’ar, M. Y. M. A., & Boonsuk, Y. (2021). What hinders English speaking in Thai EFL learners? Investigating factors that affect the development of their English speaking skills. MEXTESOL Journal, 45(3). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=23677

Sha’ar, M. Y. M. A., Buddharat, C., & Singhasuwan, P. (2022). Enhancing students’ English and digital literacies through online courses: Benefits and challenges. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 23(3), 153-178.https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tojde/issue/70682/1137256#article_cite

Somdee, M., & Suppasetseree, S. (2013). Developing English speaking skills of Thai undergraduate students by digital storytelling through websites. Proceeding of Foreign Language Learning and Teaching, 166-176. http://sutir.sut.ac.th:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/4169

Songsiri, M. (2007). An action research study of promoting students’ confidence in speaking English [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Victoria University. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/1492

Soureshjani, K. H., & Riahipour, P. (2012). Demotivating factors on English speaking skill: A study of EFL language learners and teachers’ attitudes. World Applied Sciences Journal, 17(3), 327-339. https://www.idosi.org/wasj/wasj17(3)12/10.pdf

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in science education, 48, 1273-1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Waluyo, B., & Rofiah, N. L. (2021). Developing students' English oral presentation skills: Do self-confidence, teacher feedback, and English proficiency matter? MEXTESOL Journal, 45(3). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=23771

White, A. R. (2019). A Case study: Exploring the use of the line application for learning English at a Thai public university. Rangsit Journal of Educational Studies, 6(1), 1-11. https://rsujournals.rsu.ac.th/index.php/RJES/article/view/2204/1718

Yuh, A. H., & Kaewurai, W. (2021). An investigation of Thai students’ English-speaking problems and needs and the implementation collaborative and communicative approaches to enhance students’ English-speaking skills. The Golden Teak: Humanity and Social Science Journal, 27(2), 91-107. https://so05.tcithaijo.org/index.php/tgt/article/view/252425

[1] LINE is a popular messaging and communication application. It was developed by the Japanese company LINE Corporation and was first released in 2011. LINE offers a wide range of features, including instant messaging, voice and video calls, stickers and emojis, social networking, and various other multimedia functions.