Introduction

The pandemic brought a drastic change in education around the world. Face-to-face classes shifted rapidly and unexpectedly to distance learning using e-learning methodologies (Affouneh et al., 2020). Without the outbreak of the pandemic, our schools and universities would not have begun using distance learning as pervasively, and Ecuador was no exception. On March 12, 2020, The Ecuadorian Secretary of Higher Education Science, Technology, and Research (edusuperorec, 2020) and the Ecuadorian Universities, Polytechnic Schools, and Higher Institutes agreed to stop all academic activities nationwide. Classes in all educational levels immediately began taking place in a virtual environment. This situation caused several issues with various online teaching platforms, revealing a lack of resources and prior experience in using such platforms, as well as poor Internet connectivity (Lepp et al., 2021), just to mention a few of the problems teachers and students faced during that period.

The pandemic forced schools and universities to close their doors and start teaching with various virtual platforms. This new way of teaching and learning became a challenge not only for teachers, but also for students and their families. However, Oraif and Elyas (2021) found that remote learning can create an active class environment that fosters student cooperation, enhances a dynamic and interactive class environment, and engages and motivates students in the learning process depending on the influence of different factors such as the internet connection, major, students’ participation, schedule, and even gender. Thus, the pandemic showed teachers and students the effectiveness and potential of this new way of teaching and learning (Adnan & Anwar, 2020). However, studying at home created challenges as students were distracted by different situations not encountered at school. In this regard, it is important to inquire about students’ perceptions of their level of motivation and engagement during virtual classes and its correlation with factors that facilitate or hinder them, topics addressed in this paper.

Review of the Literature

Education in the COVID-19 era

Over three years after the beginning of the pandemic, the current online learning environment has spurred teachers and students to discover new technologies and implement new ways of obtaining and using information in class (Alshehri et al., 2020), which might be a giant step in education. Online learning uses Information Technology (IT) to suit a wide range of educational styles. This innovation helps students and teachers to interact in positive ways (Alshehri et al.).

This kind of education has advantages and disadvantages. Mahyoob (2020) pointed out that schools have capitalized on “the accessibility of online education globally, saving time, money, and effort…. The teachers are reviewing and preparing well for recording, which certainly improves teaching strategies and methods” (pp. 352-353). He also mentioned the accessibility students have to teachers’ lectures anytime they want, which can help them review material to better understand their study subjects. He also noted some disadvantages. For example, in some cases, students do not have the necessary tools to connect to virtual classes, or they may even have internet connection problems, among other issues.

Prensky (2020) pointed out that nowadays students are very skilled in the use of technology. This allows them to participate actively in their virtual classes. In this sense, he suggested that EFL teachers should integrate technology effectively in their classes as a way to motivate students. This is not easy as in some situations teachers are not very skilled in the implementation of technology in their classes (Trust & Whalen, 2020); however, with the necessary instruction, this weakness could become a strength.

Online learning

In today’s world, internet access has made it possible for most people to have a better quality of life; in this way, it increases a country’s prosperity (Olivares Carmona et al., 2018). Consequently, not only learning, communication, and culture can be supported by its use, but also people can be better prepared to face the new challenges that this ‘new’ world brings (Vera Noriega et al., 2014). Education around the world is one of the many fields that has been influenced by the appearance of this digital culture, urging an essential need for this area to be modernized (Freire, 2009). Regarding this change, the transformation process from traditional education to digital education has been considered for a long time. However, this process needs to emphasize equal possibilities for everyone (Beltrán Llavador et al., 2020), as in some places, students are not able to keep up with this challenge due to lack of access to the internet, or not enough devices for the household, which makes it impossible to meet their academic commitments. This situation makes online learning face structural problems in some areas (Carla Silva et al., 2020).

Research has been conducted on how high school students in Ecuador had access to distance learning tools, as well as their engagement in this kind of education during the pandemic (Asanov et al., 2020). According to these authors, both teachers and students demonstrated flexibility. Even though some of them did not have access to the internet at home, they managed to give and attend their online classes. The Ministry of Education in the country implemented some useful alternatives for those students who do not have the necessary tools to connect to their classes. One of these was educational content broadcast by television or radio, as the majority of students have access to them.

It is important to mention that besides a lack of sufficient technological tools, teachers around the world at first lacked preparation for virtual teaching and were not trained in using tools to design quality material (Trust & Whalen, 2020). These problems can limit students’ involvement in in-class activities and negatively affect learning processes. Besides, Gururaja (2021) found that teachers did not have previous knowledge about working in an online environment and did not feel very comfortable using their Information Communication Technology (ICT) skills.

Engagement and motivation

It is known that the pandemic experience changed English education, as nowadays online English courses offer some advantages, such as more flexibility, accessibility, and the opportunity to reach a wider group of students. Nevertheless, it is necessary to take into account that students’ level of engagement and motivation in these environments might be crucial for effective learning.

Engagement and motivation play a fundamental role in learning, and of course, online learning is not an exception. On the one hand, motivation, especially intrinsic motivation, is a key element of academic engagement and performance (De la Barba et al., 2016). On the other hand, engagement is related to students’ active participation and attention to the learning task (Fredricks et al., 2004). Both elements (motivation and engagement) could be necessary for success in online English classes.

Despite the many advantages that online education offers, there can also be significant challenges that could affect students’ engagement and motivation. Among the most mentioned ones, screen fatigue, which leads to eyestrain, difficulty in concentrating on important tasks, and other physical problems, are some of the things that need to be considered (Silva et al., 2020). Online education can also lead students to feel overwhelmed, and of course, it could decrease their interest in studying (Saidi & Al-Mahrooqi, 2012). In this sense, students may be overloaded by technology, which affects their level of motivation and engagement (Meşe & Sevilen, 2021).

Additionally, students’ self-discipline is a significant factor in online education (Carla Silva et al., 2020). As mentioned by Ahmed et al. (2019), it is imperative, as teachers, to promote in the students a sense of being independent learners in order to increase their level of motivation and engagement. In this regard, it is necessary to implement strategies that enhance EFL online students’ motivation and engagement.

Students engagement and motivation in learning

Student success in academia shows an important connection with their engagement (Muzammil et al., 2020). The interest in researching student engagement is not new. It has been demonstrated that students’ accomplishment is closely associated with their relative engagement (Meşe & Sevilen, 2021). However, motivation, what drives individuals to accomplish excellent or nearly excellent levels of performance (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012), and engagement, “the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience” (Astin, 1984), in online learning environments are a recent topic of attention (Kyewski & Kramer, 2018; Özhan & Kocadere, 2019), especially now that education relies much more on technology, due to the pandemic (Oraif & Elyas, 2021).

Motivation and engagement in online learning settings are considered complex issues. Hartnett et al. (2011) reported that EFL students do not participate actively in online classes. De Barba et al. (2016) mentioned that when learning, students’ participation can be linked to intrinsic motivation, which is also connected to engagement. In this way, intrinsic motivation is important in online class environments, as not only the number of activities, but also the content presented in the virtual class can influence students’ attention. Likewise, Chen and Jang (2010) recommended paying special attention to lowering students’ feelings of nervousness and insecurity. Furthermore, Asanov et al. (2020) found that students who are not engaged in in-class activities are usually the ones who come from a poorer background. However, there is no evidence of school attendance in regular face-to-face classes with which to compare.

Learners’ engagement and motivation in English learning

Different factors influence and determine EFL students’ engagement and motivation. Findings indicate that a variety of features can contribute to students’ success or failure in learning English including gender, schedule, and discipline area. This suggests that such factors need to be taken into consideration to succeed.

In this sense, it is important to mention some previous studies that reported the influence of the mentioned factors. The first one is gender. As described by Bećirović (2017), Mori and Gobel (2006), and Saidi and Al-Mahrooqi (2012), gender plays an important role in this regard. This is because men and women do not have the same level of engagement in EFL learning. The same authors found that female EFL students showed higher motivation to learn the target language, which of course influenced their level of engagement and achievement. Saidi and Al-Mahrooqi (2012) reported that feelings and emotions have a very important impact on EFL learning. They also mentioned that female EFL learners are better than male students when trying to understand a written or oral piece of language, as they usually contain lots of emotions and feelings. This, of course, affects male learning strategies. as they have to work harder on the language to be able to understand it.

At this point, it is necessary to mention the role motivation plays in students’ engagement as it is influenced by cognition, consciousness, and emotions. This could affect how learners structure and perform any learning activity (Eccles & Wang, 2012). In this regard, Dörnyei (1998) asserts “…that motivation is indeed a multifaceted rather than a uniform factor” (p. 131). He developed a language learning motivation framework that includes three stages: “(1) the Language Level, (2) the Learner Level, and (3) the Learning Situation Level” (p. 125). The first is a general stage where students’ engagement is affected by the student’s reason(s) for learning the language; it is an integrative and instrumental stage. The second stage is influenced by learners’ characteristics in relation to their perceptions and expectations such as competence, achievement, and efficacy in using the language. The third stage is influenced by the course, the teacher, and the group components.

Regarding the influence of motivation and engagement on different aspects of students’ academic life, Fredricks, et al. (2004) identified three different dimensions of engagement (emotional, behavioral, and cognitive). The authors stated that these three play a fundamental role in students’ academic engagement which could positively influence learning and performance. However, they highlighted the necessity of agreeing on the definition of those dimensions. In the same vein, Kahn (2014) proposed a framework for academic engagement in higher education, again based on three dimensions, similar to Fredricks et al. (2004). Kahn described the importance of cognitive and emotional engagement, but instead of behavioral engagement, the author proposed social engagement as an important component for academic engagement. In order to have better results in academic performance, there might be an interrelation among these three types of engagement which were called cognitive, emotional, and social. López-Aguilar et al. (2021) also mentioned the importance of encouraging academic engagement to benefit students’ academic performance.

In the specific field of virtual education, Redmond et al. (2018) mentioned the students’ need for permanent interaction, collaboration, and feedback in online classes to promote their active participation and academic success. Similarly, Santana Villegas and Santana (2021) studied virtual environments and escape-rooms in higher education. These authors concluded that through interactive and participatory classes it is possible to promote long-term learning and students’ academic engagement, crucial elements in academic success.

For the above mentioned, it was essential to study the perceptions that EFL students enrolling in different levels at the University of Cuenca - Ecuador had about their virtual learning process to shed light on how this suddenly-and widely-imposed methodology, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, was implemented, and to help future researchers, educators, and policy makers improve this education modality. As such, the present study attempts to answer the following research question:

To what extent can factors such as gender, schedule, and discipline area predict students’ level of motivation and engagement in EFL online classes?

Method

The study took place in the Language Department with the students of the Foreign Language Proficiency Academic Program (PASLE in Spanish) at the University of Cuenca. A correlational study was carried out to analyze the possible associations of different conditions and variables (Mertens, 2015). A quantitative design was used to evaluate these associations statistically and find these relations in an objective way (Creswell, 2014).

This investigation intended to study the degree in which gender, schedule, and discipline area influence EFL students motivation and engagement in their online classes

Procedures

Permission of the Language Department and its Committee at the University of Cuenca was sought. After obtaining the needed permissions, EFL students were invited to be part of this research. All the teachers from the Language Department sent an online survey to their students and motivated them to participate. These students completed the survey where the objective, potential benefits, confidentiality, and privacy rights, as well as implications of the study, were explained. After reading this information online, students knew they could answer the survey if they wanted to do so. To preserve confidentiality and anonymity, each student was given a unique code (Mackey & Gass, 2005).

Participants

Students from different fields of study at the University take classes at the PASLE program aiming to reach the B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages required to obtain the certified title at the University (Council of Higher Education, 2019). These students intend to reach the required level with three EFL levels (A1, A2, and B1) after taking a placement test. However, the students who want to reach a B2 level can take one more semester which is also offered by the PASLE program.

Due to the pandemic, the University and its Language Department implemented online classes beginning in March 2020 (edusuperorec, 2020). In this regard, it is important to mention that the Language Department continued devoting its teachers’ efforts to develop their students’ four skills of the language (listening, reading, speaking, and writing) (Language Department, personal communication, March 2020).

Seven hundred and three EFL students of different levels (A1, A2, B1, and B2) with ages (from 18 to 33 and more), different fields of study (Social Science, Biological Science, and Engineering), and different schedules (morning, afternoon, and evening) at the University agreed to participate and answered the online survey about the level of motivation and engagement they have in their online classes. A convenient sampling procedure was used. EFL teachers at the language department shared the survey with their students; however, students were free to complete the survey or not.

Instrument

The questionnaire used in this investigation measured students’ perceptions of their level of motivation and engagement in their online EFL classes by assigning different items to each of them within the same instrument (See Appendix). It was adapted and translated into a Spanish version of the survey conducted by Oraif and Elyas (2021). This instrument measured both engagement and motivation separately. To validate this translated version of the questionnaire, it was then checked by three EFL University teachers who suggested some changes to clarify the instrument. After adapting and validating the instrument and reviewing the literature, it was observed that for this research-specific context and based on Dörnyei’s (1998) framework, four dimensions were used to classify the questionnaire: (1) Language Level, (2) Learner Level, (3) Learning Situation Level, and (4) Performance Level (this last dimension was added to the three previous ones mentioned by Dörnyei).

The translated, adapted, and validated scale proved highly reliable, as reported with Cronbach's Alpha coefficient (α=0.918) for the 22 question items of the questionnaire. By performing a correlational analysis (KMO =0.922 and Bartlett's Sphericity p=0.000) using the unweighted least squares method (Lovia Boateng, 2020) with Varimax rotation, it was possible to explain at least 50% of the variance by a natural grouping of four dimensions: (1) Language level engagement; (2) Learner Level; (3) Learning Situation Level; and (4) Performance Level. After obtaining the University of Cuenca Language Department’s permission, the survey was ready to be sent using Google Forms. A link to the survey was sent by mail to the PASLE teachers who asked their students to participate in this study.

IBM SPSS 25 software was used to analyze data (Field, 2018). Descriptive statistics to calculate central tendency measures (means), variability measures (Standard deviations), and minimum and maximum values for each dimension measure were used. The distribution of each dimension of the level of EFL students’ engagement was explored.

Data Analysis and Results

The results were analyzed with the SPSS 25 program and are presented using descriptors in frequencies and percentages for the student profile, as well as the five-point scale in averages and standard deviations (SD) for the results of the four dimensions. In order to measure the central tendency with the value provided by the median, these results are compared using nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis H and Mann-Whitney U statistical tests to compare dimensions such as discipline area, schedules, and gender. These statistical tests were used to ensure the homogeneity of the variance.

Table 1 shows the results of the profile of the students who participated in the study. The participants studied at one of the four levels offered by the Language Department, the most frequent being level A2, which corresponds to 54.8%. The age of the students was mainly between 18 and 22 years old (84.6%). Of the surveyed students, 81.6% were originally from the city of Cuenca, the others came from neighboring cantons and provinces. Most participants were students in the fields of Social Sciences (52.8%), followed by Biological Sciences (35.2%) and Engineering (12%). The schedules in which they took English classes were mainly in the afternoon (45.2%) and evening (32.5%). 97% of students used activities and links available on the University's platform, but only 73.8% relied only on the activities available on this medium. This means that 23.2% looked for more sources of extra practice. Most students were satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the synchronous classes.

Table 1: Participants’ profiles

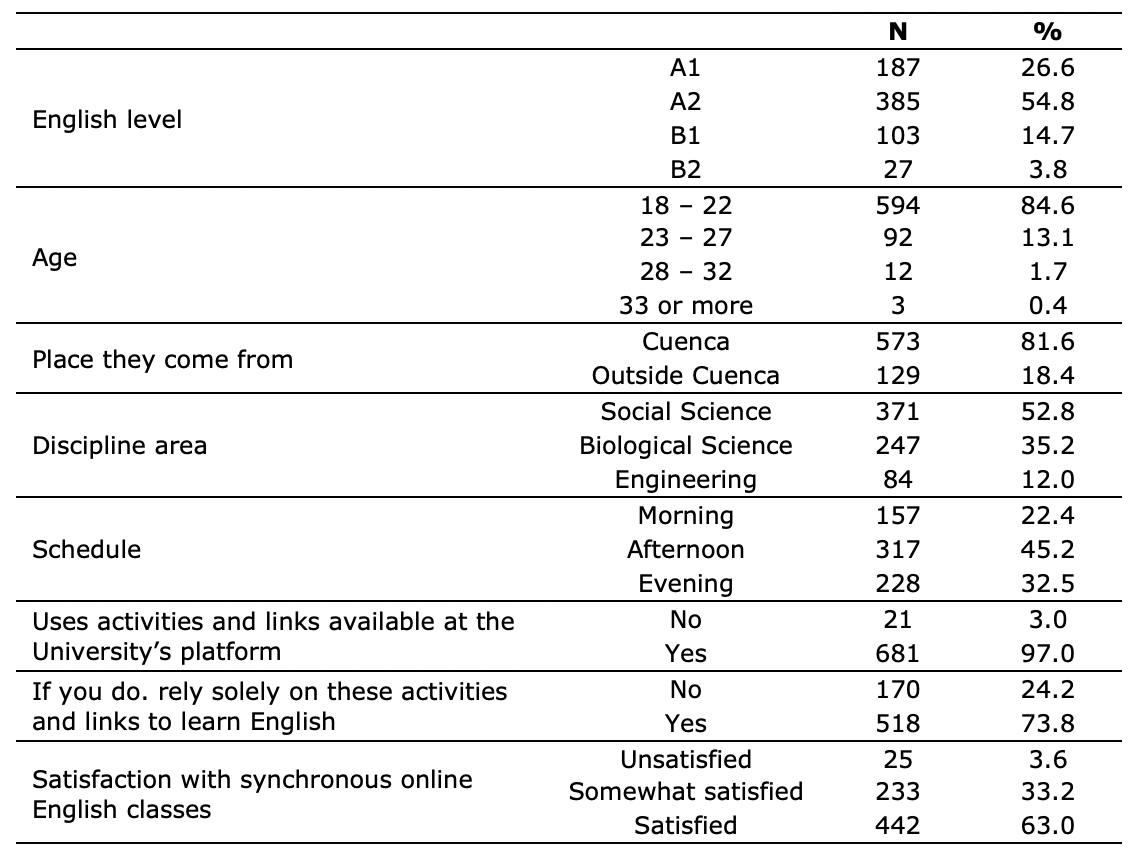

The results of the four dimensions are shown in Figure 1. The dimension with the highest number of students corresponds to the Learner Level (Mean 4.35; SD 0.53), which differs significantly from the others. At an intermediate level are Language Level (mean 3.82; SD 0.66) and Performance Level (Mean 3.88; SD 0.64). Below all the dimensions indicated, Learning Situation Level (Mean 3.63; SD 0.70) is found, which is significantly lower than Language Level and Performance.

Note: CI stands for the coefficient interval at 95%

Figure 1: Averages of the four studied dimensions (Language level engagement, Learner level, Learning situation level, and performance level)

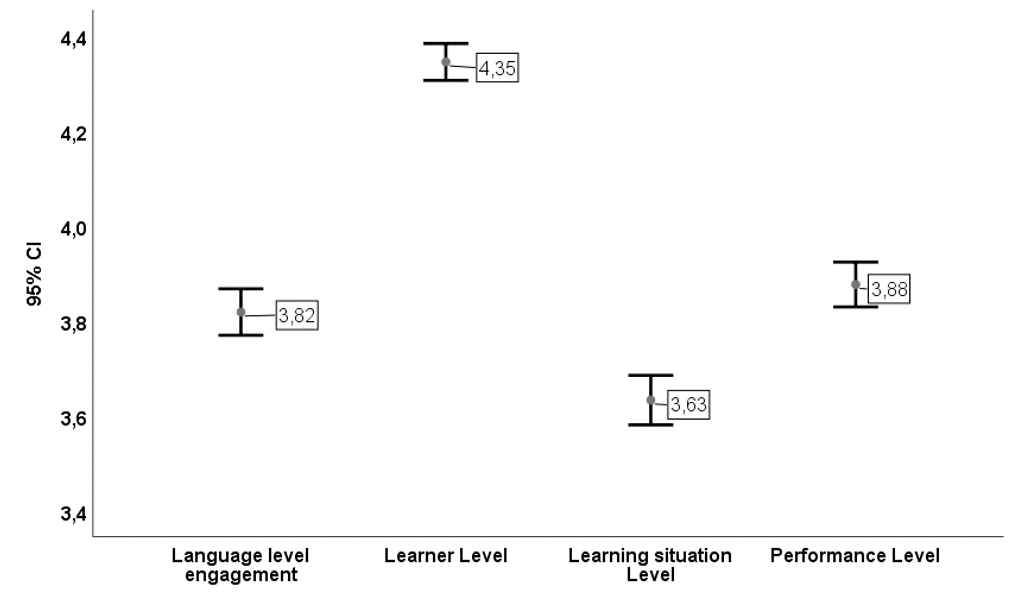

Figure 2 reports the results according to the areas of knowledge and only significant differences were found within the Learner Level variable (Kruskal-Wallis H (2gl) = 6.83; p=0.033). When comparing areas of knowledge, a significant difference was found only at the Learner Level, which shows that students in Social Sciences have a significantly higher average than those in Engineering (Z=-2.388; p=.017), the mean of Social Sciences is 4.39 (SD 0.50) and that of Engineering is 4.29 (SD 0.44).

Figure 2: Averages of the four dimensions according to the discipline area

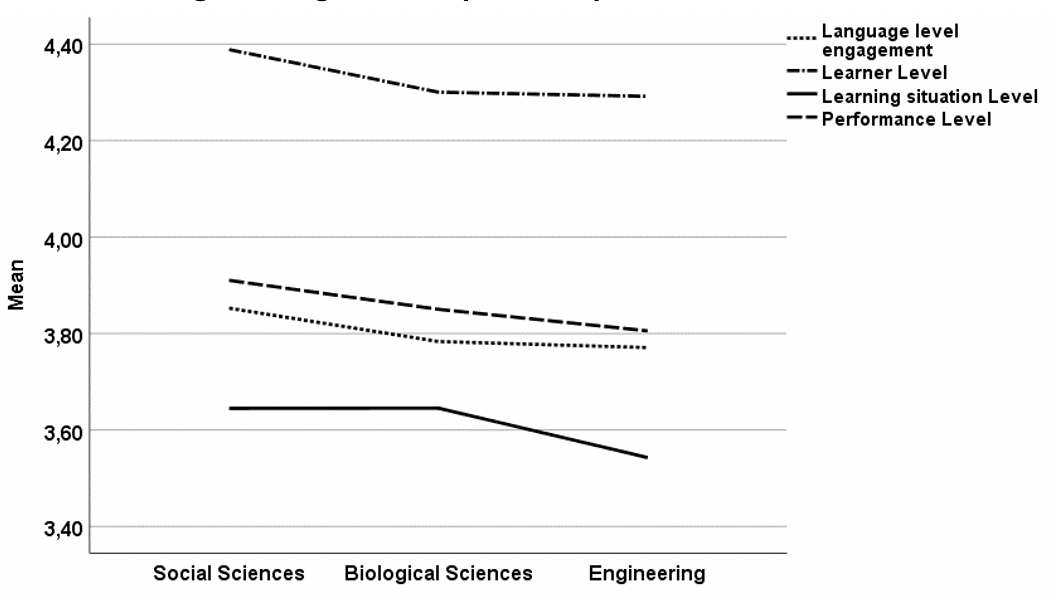

Figure 3 shows the correlations between class schedules and the three modalities (morning, afternoon, and evening). In this regard, differences were found in the variables Language Level (Kruskal-Wallis H (2gl) =8.87; p=0.012) and Learning Situation Level (Kruskal-Wallis H (2gl) = 9.42; p=0.009). The difference between schedules for Language Level was between the afternoon, which obtained a mean of 3.88 (SD 0.64), and the evening, which obtained 3.71 (SD 0.69), a difference that is considered statistically significant (Z=-2.99; p=0.003). Furthermore, the variable Learning Situation Level revealed differences between the morning which obtained an average of 3.75 (SD 0.72), and the night which average is 3.55 (SD 0.67), a statistically significant difference (Z=-3.15; p=0.002).

Figure 3: Line diagram of the averages of the four dimensions according to the EFL students’ schedules.

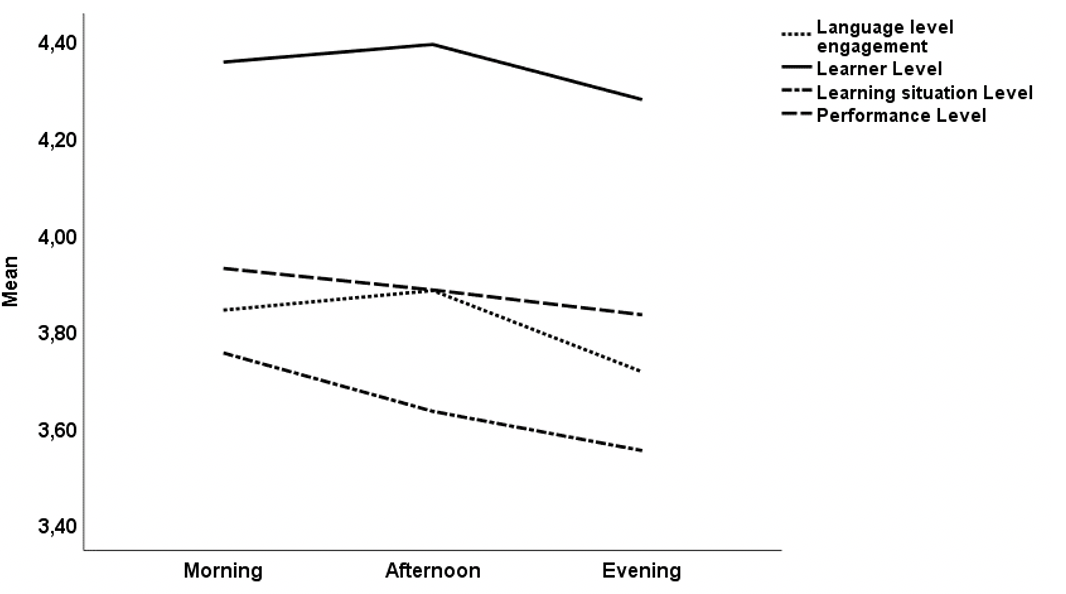

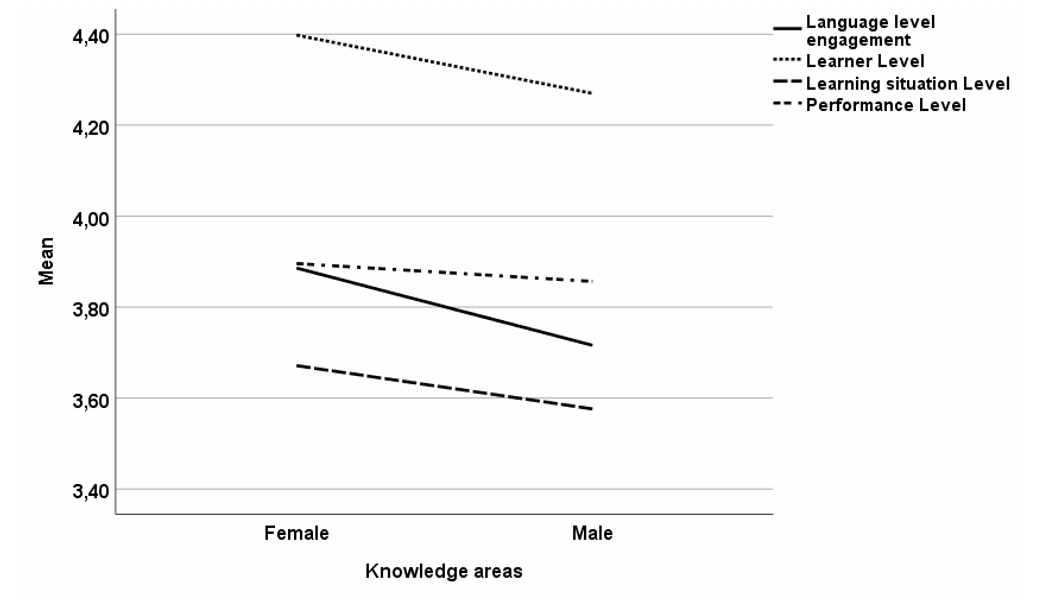

Figure 4 shows the results of comparing the students’ gender. Language Level and Learner Level show statistically significant differences between males and females. Females obtained an average of 3.89 (SD 0.64) and males 3.72 (SD 0.69), a difference that is considered statistically significant (Z=-2.95; p=0.003) in Language Level. Women also exhibited a higher average of 4.40 (SD 0.49) than men 4.27 (SD 0.54), a statistically significant difference (Z=-3.51; p=0.000) in the Learner Level dimension.

Figure 4: Averages of the four dimensions according to gender

Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore the influence that some factors have on EFL students’ level of motivation and engagement in their online classes. The results show that the factors that affect students’ motivation and engagement in online classes are, from the most to the least important, discipline area, gender, and schedule. In addition, there is a significant difference in the learner level dimension between the two groups, students who are studying Social Science and the ones studying Engineering. It seems that students who are not in the hard sciences have a preference for online learning. This situation could happen because, in online EFL classes, students are usually engaged in analyzing things, discussing different situations, and debating about a variety of topics which are learning strategies generally used in the social science fields.

Gender can also influence the level of EFL students’ motivation and engagement. This study found that in the Language Level and Learner Level dimensions, females are more engaged in online classes than men. Bećirović (2017) explained that women feel more motivated and enthusiastic when learning a language, which could explain why they more frequently sustain this feeling in online classes. It seems to be a reality that female students from Cuenca, Ecuador also face in their EFL online classes. The current results could also be compared with those of Saidi and Al-Mahrooqi (2012), who maintained that women could overcome anxiety and tension in an educational environment more easily than men, which could be the reason women have a significantly higher level of motivation and engagement. Moreover, Oraif and Elyas (2021) also found that EFL female learners showed a positive attitude towards online learning; hence, it can be an indicator of course motivation and engagement. In this regard, it looks like female students can adapt themselves smoothly to different learning environments which influences their level of academic engagement and motivation.

The University of Cuenca offers EFL classes during morning, afternoon, and evening schedules, and each student can situate their EFL classes in a given schedule according to the student’s needs and availability. In this study, two situations were found. In the Language Level dimension, afternoon students were more engaged and motivated than evening students. In the Learning Situation Level dimension, morning students proved to be more motivated and engaged than evening students. In both dimensions, evening students exhibited less motivation and engagement in the EFL online classes. This finding resembles Andreoli and Martino’s (2012) findings that showed that morning students performed better than evening students. Perhaps due to the morning students’ perception of better academic performance, they also feel more motivated and engaged in classes than the evening students. Conversely, they also mentioned that later bedtimes can be linked to lower academic performance, which suggests an effect of night shift studying. Regarding schedule, participants in this study mentioned they feel pleased as in online classes it is easier for them to find and choose the schedule that better encompasses the different needs and obligations they have. It is well known that after a restoring night, students might be more productive and energetic which could increase their levels of engagement and motivation in EFL online classes. Based on the results and discussions, the study puts forward the following recommendations.

Recommendations

EFL virtual classroom environments are places where students feel satisfied and can learn and use the target language. This is not only because they are required to use the target language using links and virtual material uploaded to the regular institutional platform, but also because they search out other virtual sources which can foster language competence. EFL teachers should take advantage of the situation, using it as an opportunity to improve their students’ academic achievement and to motivate them to develop not only their language competence but also their critical thinking to promote other meaningful learning experiences.

Female EFL/ESL students display keener interest and are more motivated and engaged in the learning process, and they seem to be able to manage academic stress and anxiety more effectively. Future research is indicated to explore whether there is a different level of motivation and engagement in the same population between virtual and face-to-face classes.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the educational system globally, opening several possibilities for implementing helpful new methods and approaches to teaching and learning. This study’s results indicate it is necessary to consider that attending to the learner level is necessarily essential for EFL virtual education. This is because students’ own reasons and intentions for learning the language play a fundamental role in their level of motivation and engagement. Besides needing to meet the university’s requirements to achieve a certain level of target language proficiency in order to graduate, students’ other personal reasons to take these classes might affect their level of motivation and engagement in EFL classes. A fundamental aspect to consider is the fact that the learning situation level needs to be attended to since being at home or in any other place which was not designed for educational purposes might influence students’ level of concentration and attention span. In this sense, teachers play a fundamental role in helping their students increase their motivation and engagement in the language learning process. Also, the EFL/ESL class should provide a variety of dynamic tasks and assignments using available technological resources and websites, while also employing a variety of methodologies and approaches to take advantage of such opportunities in language learning. Taking this situation into account might have important implications in EFL/ESL teaching and learning as students and teachers can take more advantages of the teaching and learning process.

EFL teachers need to pay more attention to their students who take their classes at night, as they appear to be the least motivated and engaged students. Many factors need to be considered as after a long studying or working day; learners may want to rest and relax, which is why EFL instructors need to provide many meaningful and interactive activities, plus a variety of opportunities for learners to use the target language in class. This can get them motivated and engaged in the process, which can decrease students’ anxiety and fatigue and increase their concentration and enjoyment while studying during the night shift. Fostering students’ interaction should also increase students’ motivational and engagement level in EFL virtual night classes.

References

Adnan, M., & Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students' perspectives. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 2(1). 45-51. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPSP.%202020261309

Affouneh, S., Salha, S.N., & Khlaif, Z. (2020). Designing quality E-Learning environments for emergency remote teaching in Coronavirus crisis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences, 11(2). 1–3. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijvlms.2020.86120.1033

Alshehri, Y. A., Mordhah, N., Alsibiani, S., Alsobhi, S., & Alnazzawi, N. (2020). How the regular teaching converted to fully online teaching in Saudi Arabia during the Coronavirus COVID-19. Creative Education, 11(7). 985-996.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2020.117071

Andreoli, C. P. P. & Martino, M. M. F. (2012). Academic performance of night-shift students and its relationship with the sleep-wake cycle. Sleep Science, 5(2). 45-48. https://sleepscience.org.br/export-pdf/55/v5n2a03.pdf

Asanov, I., Flores, F., McKenzie, D., Mensmann, M., & Schulte, M. (2021). Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Development, 138. 2-25.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105225

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25(4), 297–308. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-18630-001

Bećirović, S. (2017). The relationship between gender, motivation, and achievement in learning English as a foreign language. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 6(2). 210-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2017.2.210

Beltrán Llavador, J., Venegas, M., Villar-Aguilés, A., Andrés-Cabello, S., Jareño-Ruiz, D. & de Gracia-Soriano, P. (2020). Educar en época de confinamiento: La tarea de renovar un mundo común [Educating in the Age of Enclosure: The Task of Renewing a Common World]. Revista de Sociología de la Educación, 13(2). 92-104.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7203/RASE.13.2.17187

Boateng, S. L. (2020). Structural equation modeling made easy for business and social science research using SPSS and AMOS. Amazon Digital Services.

Council of Higher Education (CES). Regulation of Academic Regime Resolution, 111 Official Register 473 art. 80 of April 23, 2019

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach (4th ed.). Sage

De Barba, P. G., Kennedy, G. E., & Ainley, M. D. (2016). The role of students' motivation and participation in predicting performance in a MOOC. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(3). 218-231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12130

Dörnyei, D. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31(3). 117-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

Eccles, J., & Wang, M.-T. (2012). Part 1 commentary: So what is student engagement anyway? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 133–145). Springer

edusuperorec [@EduSuperiorEc]. (2020, March 12). Sobre las actividades académicas en las Instituciones de Educación superior a nivel nacional ante la #Emergencia Sanitaria declarada en el país [About the academic activities in Higher Education Institutes at a national level due to the #Sanitary Emergency declared in the country]#. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/EduSuperiorEc/status/1238141139326316545/photo/1

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Freire, J. (2009). Cultura digital i pràctiques creatives en educació [Digital culture and creative practices in education]. RUSC Universities and Knowledge Society Journal, 6(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v6i1.23

Gururaja, C. S. (2021). Teachers’ attitude towards online teaching [Conference presentation]. National Virtual Conference “New Education Policy: A Quality Enhancer for Inculcation of Human Values in Higher Education Institutions,” Chennai, India. 8-10 June.

Hartnett, M. (2016). The importance of motivation in online learning. In M. Harnett (Ed.) Motivation in online education (pp. 5-32). Springer.

Kahn, P. E. (2014). Theorising student engagement in higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 40(6), 1005-1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3121

Kyewski, E., & Krämer, N. C. (2018). To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Computers & Education, 118. 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.006

Lepp, L., Aaviku, T., Leijen, Ä., Pedaste, M., & Saks, K. (2021). Teaching during COVID-19: The decisions made in teaching. Education Sciences, 11(2). 11-47. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020047

López-Aguilar, D., Álvarez-Pérez, P. R., & Garcés-Delgado, Y. (2021). El engagement académico y su incidencia en el rendimiento del alumnado de grado de la universidad de La Laguna [Academic engagement and its impact on the performance of undergraduate students at the University of La Laguna]. RELIEVE, 27(1). http://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v27i1.21169

Mahyoob, M. (2020). Challenges of e-Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

experienced by EFL learners. Arab World English Journal, 11(4). 351-362.

https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no4.23

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mertens, D.M. (2015). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (4th ed.). Sage.

Meşe, E., & Sevilen, Ç. (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: A qualitative case study. Journal of Educational Technology & Online Learning, 4(1). 11-22. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jetol/issue/60134/817680

Mori, S., & Gobel, P. (2006). Motivation and gender in the Japanese EFL classroom. System, 34(2). 194-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.11.002

Muzammil, M., Sutawijaya, A., Harsasi, M. (2020). Investigating student satisfaction in online learning: The role of student interaction and engagement in distance learning university. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(Special Issue), 88-96. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.770928

Olivares Carmona, K. M., Angulo Armenta, J., Prieto Méndez, M. E. & Torres Gastelú, C. A. (2018). EDUCATIC: Implementación de una estrategia tecnoeducativa para la formación de la competencia digital universitaria [EDUCATIC: Implementation of a techno-educational strategy for university digital competence training]. Píxel-Bit, 53. 27-40. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.02

Oraif, I., & Elyas, T. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on learning: Investigating EFL learners’ engagement in online courses in Saudi Arabia. Education Sciences, 11(3). 1-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030099

Özhan, Ş. Ç., & Kocadere S. A. (2019) The effects of flow, emotional engagement, and motivation on success in a gamified online learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633118823159

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5). https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/10748120110424816/full/html

Redmond, P., Abawi, L.A., Brown, A., Henderson, R., & Heffernan, A. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education.Online learning, 22(1), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1175

Saidi, A. A., & Al-Mahrooqi, R. (2012). The influence of gender on Omani college students’ English language learning strategies, comprehension, and motivation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 1(4). 230-244. https://doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.4p.230

Santana Villegas, J. C.., & Santana, F. J. (2021). Entornos virtuales de aprendizaje colaborativo y "escape rooms" en la Educación Superior [Collaborative virtual learning environments and "escape rooms" in higher education]. In O. Buzón-García & M. del C. Romero García (Eds.) Metodologías activas con TIC en la educación del siglo XXI (pp. 426-444). Dykinson.

Silva, T. C., Ramos, E. & Montanari, R. (2020). Dificultades de la educación remota en

las escuelas rurales del norte de Minas Gerais durante la pandemia de Covid-19 [Difficulties of remote education in rural schools in northern Minas Gerais during the Covid-19 pandemic]. Research, Society and Development, 9(8). 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i8.6053

Tohidi, H., & Jabbari, M. M. (2012). The effects of motivation in education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31. 820 – 824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.148

Trust, T., & Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2). 189–199. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/215995

Vera Noriega, J. A., Torres Moran, L. E., & Martínez García, E. E. (2014). Evaluación de competencias básicas en TIC en docentes de educación superior [Assessment of basic ICT competencies in higher education teachers]. Píxel-Bit, 44. 143-155. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2014.i44.10