Introduction

COVID-19 or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) all parts of life, such as health, religion, economy, education, tourism, industry, and cultures (Carr, 2020; Guan et al., 2020; Hasan & Bao, 2020; Koenig, 2020) In education, the majority of colleges made a spontaneous change in their curricula, changing from conventional to digital modes. (Crawford et al., 2020). Numerous teachers and educational practitioners were unable to utilize technology to support their teaching because of their limited technological l knowledge (Sahu, 2020; Saputra, 2018; Saputra & Fatima 2018). Also, myriad universities carried out a campus closure policy to stop spreading the virus among teachers and students (Sahu, 2020). Given these facts, moving the concept of conventional to online language teaching and learning practices was demanding during the pandemic.

Like many countries affected by the pandemic, the Indonesian educational system suffered at all levels, from elementary to tertiary education. As an example, the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia (MONEC) decided to close educational facilities to mitigate the spread of the virus and proposed to conduct online teaching and learning practices (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2020). However, this sudden policy change caused new problems both for teachers and students, such as extending the gap between the wealthy and the poor students (Yarrow et al., 2020), saturating and stressful learning activities (Brazendale et al., 2 017), and unfamiliar and abrupt teaching practices. To illustrate, students engaging in teaching and learning practices during the pandemic tended to experience frustration, uncertainty, ineffective time management, demotivation, cheating and unhealthy work life (Ahmed et al. 2020). These occurred because of the implementation of unfamiliar new teaching practices in which the teachers themselves were just adjusting their teaching beliefs and methodology, and discovering their preferred instructional media. As a result, these situations could influence students' learning engagement.

Although there are assorted types of learning engagement commonly performed by students in the classrooms (e.g., cognitive, behavioural, and emotional engagement) (Abdullah et al., 2020; Fredricks et al., 2004; Hong et al., 2020; Wang & Degol, 2014; Yundayani et al., 2021), emotional engagement is claimed to have more substantial effects on the relationship between students and teachers (Sciarra & Seirup, 2008), particularly during pandemic-stricken learning activities (Chiu, 2021). Emotional engagement involves students' affective responses, relationships with academic-related objects (e.g., peers, teachers, and the school itself), and school-related belongingness (Fredricks et al., 2004; Sciarra & Seirup, 2008). This is valuable when it leads to positive emotions that motivate students to perform affirmative behaviours and repetitive actions (Fredrickson, 2001). Equally, Walker et al. (2006) and Hong et al. (2020) maintain that positive engagement affects students' cognitive engagement related to teaching and learning practices, such as identifying, belonging, and valuing. In this case, Students should be motivated to be actively involved in classroom activities and aware of their learning objectives. Guiding them to identify what and how to attain the intended learning objectives is a cornerstone that helps them engage cognitively. Another practice is raising their awareness that they belong to a particular academic environment (e.g., a class, a school, a faculty, a university) so that they understand their rights and responsibilities as students. Equally important, students are led to value their academic attainments by appreciating their competencies and performances during classroom practices (Osborne, 1997; Voelkl, 1996). Further, emotional engagement encourages students to engage in academic-related activities (Ladd et al., 2000). Given these facts, maintaining students’ emotional engagement during teaching and learning activities remains crucial, notably in an ERT situation.

Many investigative attempts (e.g., Ghanizadeh et al., 2020; Hiver et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2020; Ramshe et al., 2019) have focused on language learning engagement. To illustrate, Ramshe et al. (2019) examined the role of personal best goals in English as a foreign language (EFL) learners' behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement. They reported that students' personal best goals of English language learning generated their behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement. They concluded that motivating students to have positive and consistent personal best goals allows them to attain intended language learning outcomes effectively. Subsequently, Ghanizadeh et al. (2020) probed how humanistic teaching represented in teachers' error correction affects EFL learners' engagement, motivation, and language achievement. The findings revealed that cognitive, behavioural, and emotional engagements were influenced by humanistic teaching practices. In particular, emotional engagement occupied the most influence, and behavioural engagement rested in the least affected. Luan et al. (2020) explored the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement. They found that the humanistic model of instruction supports students to engage behaviourally. In addition, the mediational model of instruction also helped them enhance cognitive, emotional, and social engagements. They recommended that establishing effective instructional strategies and media enables teachers to invigorate the students' learning engagement amid the pandemic quarantine. Egbert (2020) considered that task engagement played a pivotal role in helping them to learn synchronously. Further, Egbert et al. (2019) reported that teachers can apply the language task engagement model to design engaging language tasks More recently, Hiver et al. (2021) conducted a systematic literature review on 20 years of language learning engagement research. They assumed that the studies on learning engagement indicated the employment of various methods and conceptual frameworks, upgraded explanations, and implementation of engagement in both quantitative and qualitative inquiries.

Despite this rapid increase of inquiries on language learning engagement, limited research has been conducted on the issue of emotional engagement during an ERT. In response to this gap, the present study aimed to investigate how teachers maintained the students’ emotional engagement during the ERT, especially in the Indonesian EFL context.

This study contributes practically to TESOL practitioners, students, and policymakers as benefited stakeholders. This study discusses how students' emotional engagement could be maintained while performing teaching and learning activities during an ERT to discover whether their learning engagement should be a focus of teachers while doing activities in the classroom.

Review of Related Literature

Emotional engagement in emergency teaching during COVID-19

The pandemic was challenging for everyone; however, teachers had the additional burden of supporting their learners remotely. Being isolated at home often worsened the fear of dealing with a global pandemic. In response to such a situation, motivating students through enjoyable learning activities enabled them to maintain their mental health (Anderson, 2020; Snelling & Fingal 2020). Teachers also felt isolated as they taught their classes without support from their colleagues (Abdullah et al., 2020; Murray, 2010).

Research that focuses on exploring the roles of emotional engagement has been extensively documented. For example, concerning school engagement, Yazzie-Mintz (2009) described emotional engagement as “students’ feelings of connection to (or disconnection from) their school—how students feel about where they are in school, the ways and workings of the school, and the people within their school (p. 4).” Since emotional engagement is viewed as a multidimensional and dynamic feature of language learning activities, the way to measure or describe the level of engagement remains biased (Fredricks et al., 2004; Fredricks et al., 2019; Skinner & Pitzer, 2012). Skinner et al. (2009) claimed that students’ emotional engagement could be categorized into two main types, positive emotional engagement (e.g., students’ interest, enjoyment, and enthusiasm) and emotional engagement (e.g., anxiety, frustration, and boredom). The present study attempted to characterize the students’ emotional engagement with this emotional engagement taxonomy.

Emotional engagement is also categorized into two types to represent how students learn, namely positive (eagerness, sympathy, happiness, etc.) and negative emotional engagement (nervousness, depression, apathy, etc.) (Skinner et al., 2009). Baralt et al. (2016) added purposefulness and autonomy as aspects of emotional engagement in how students interact with their classmates (Baralt et al., 2016; Yazzie-Mintz, 2009).

Emergency remote teaching

After the COVID-19 outbreak in December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified it as a global pandemic in March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). Numerous countries made efforts to limit the virus transmission by tightening health codes, recommending isolation, immunizing, and enforcing interactional confinement. Practically speaking, governments in various countries decided to close educational institutions and other non-essential working-oriented organizations. They replaced the classroom-based learning activities with virtual learning activities to avoid the spread of the virus (Trust & Whalen, 2020; Yundayani et al. 2021) However, this shift was not seen as just common online learning activities in which teachers, students, and policymakers were prepared to implement online teaching and learning practices. It framed teaching and learning practices as ERT.

Students’ emotional engagement during emergency remote teaching

Student emotional engagement amid ERT has been documented in a few studies (Aladsani, 2022; Tzafilkou et al. 2021). These studies have confirmed the trajectory of the present study by believing that ERT influenced students to engage in language learning activities. As an example, Tzafilkou et al. (2021) examined the interplay among students’ negative emotions, acceptance of (emergency) remote teaching, and self-perceived knowledge building. They showed that the students’ approval of online learning activities affected their positive and negative emotions.

Another study was conducted by Aladsani (2022) who explored t university instructors’ narratives about promoting student engagement during emergency remote teaching in Saudi Arabia. She asserted that teachers’ perceptions of the distance education transition, their teaching challenges, and the local culture and millennial generation students influenced the students' learning engagement emotionally. However, limited studies emphasized how the teachers maintained the students' emotional engagement during ERT. Therefore, this study aimed to address the gap.

This research sought to answer the following central question and sub-questions:

How did teachers maintain the students’ emotional engagement during the ERT?

- How did teachers overcome their students’ challenges during learning in the pandemic?

- What teaching strategies did the teachers apply to engage their students emotionally during the pandemic?

Method

Research design

This study employed a descriptive case study to describe how teachers maintained the students’ emotional engagement during the ERT. Merriam (1988) said that case studies refer to particularistic, descriptive, heuristic, and inductive research methods to collect and analyze various data. In other words, this research method enables researchers to gain a specific and contextualized description of certain circumstances (cases) (Yin, 2003). In addition, this method encourages researchers to understand a research issue from various perspectives. Moreover, it examines the investigated phenomenon and its context. (Baxter & Jack, 2008). The current study used such an investigative method because it indicated the appropriateness between the investigated phenomenon and its investigative purpose (Çakar & Aykol, 2021).

Setting and participants

The present study was conducted in the English Education Department of a state university in Tasikmalaya, West Java, Indonesia. This university was chosen due to the existence of an investigated phenomenon, the teachers' support of the students' emotional engagement during the ERT in two courses: Grammar in Multimodal Discourse (GMD) and Translating and Interpreting (TI) Also the Head of the English Education Department permitted this research.

The participants of this study were two teachers from the English Education Department. They were mentioned in pseudonyms, namely Kira (female) and FA (male). Their ages were approximately 31 and 32 years old. Both of the participants held an M.A. in English Language Education and their areas of expertise were English as a medium of instruction, English language education, linguistics, sociolinguistics, discourse studies, and English pronunciation. They had from three to ten years of experience. Linguistically, they actively communicated in Bahasa Sunda (L1), Bahasa Makassar (L1), Bahasa Indonesia (L2), and English (FL). Equally important, they were willing to participate in this study. They were informed of the current investigative purpose and asked to fill out and sign a consent form.

Data collection procedures and analysis

Semi-structured interviews were utilized to collect the data. This type of interview was used because it can help the researchers acquire a comprehensive view of the required data. Besides, interviews are flexible and researchers can adjust the unpredictable responses of the participants and develop them further (Heigham & Croker, 2009; Richards, 2009). The interview questions were based on several topics, namely knowledge of ERT, preparing and selecting teaching materials as instructional media, teaching methods, and techniques and evaluation (Hodges et al., 2020; Whittle et al., 2020). More specific descriptions of the interview questions adapted from Whittle et al. (2020) and Hodges et al. (2020) can be viewed in the Appendix. The interview results were recorded on a smartphone. The interviews were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia to decrease the participants' reluctance and apprehension (Papadopoulou & Vlachos, 2014). In addition, the interviews were qualitatively supported by open-ended questions to explore the ideas further (Johnson & Christensen, 2008). Once the data were collected, they were transcribed and translated into English for further qualitative data analysis.

Thematic Analysis (henceforth, TA) was selected to analyze the data. TA was regarded to be able to provide adaptable, miscellaneous, and flexible data analysis procedures (Braun & Clarke, 2006; King, 2004). Additionally, it offers more contextualized data suitable to the aim of the present study, probing how teachers maintain the students’ emotional engagement during an emergency remote teaching event.

Technically, TA-informed data analysis involves six stages. To begin with, familiarizing with the data (Stage 1) helps the researchers familiarize themselves with the collected data. Then, generating initial codes (Stage 2) allows the researchers to develop initial codes from the analyzed data to evaluate it by outlining each activity. Next, searching for themes (Stage 3) refers to the analytical stage in which the related data are classified and organized thematically. In addition, reviewing themes (Stage 4) describes the process of reviewing thematized data to decide on dependable and relevant data based on the research question(s). Likewise, defining and naming themes (Stage 5) represents the practices of identifying refined thematic data relevant to the scope of the research. Finally, producing the report (Stage 6) is the process of reporting the generated themes in the form of a written report (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Overall, Spiers and Riley (2018) conclude that TA offers possibilities to outline an operative and systematic understanding of the patterned data.

Findings and discussion

The main focus of this study was to answer the main research question: How do teachers maintain the students’ emotional engagement amid Emergency Remote Teaching? More specifically, it focuses on the following research questions, namely: What teaching strategies do the teachers apply to engage their students emotionally during ERT? How did teachers overcome their students’ challenges during learning in the ERT context? There were seven thematic findings discovered after analyzing the data: implementing proper teaching materials and instructional platforms during ERT, actualizing tolerance-based learning activities, performing self-adaptation to technology-enhanced language teaching, using contextualized teaching methods during emergency remote teaching, applying eclectic instructional media during emergency remote teaching, and utilizing constructive and humanizing online learning monitoring.

Implementing proper teaching materials and instructional platforms during emergency remote teaching

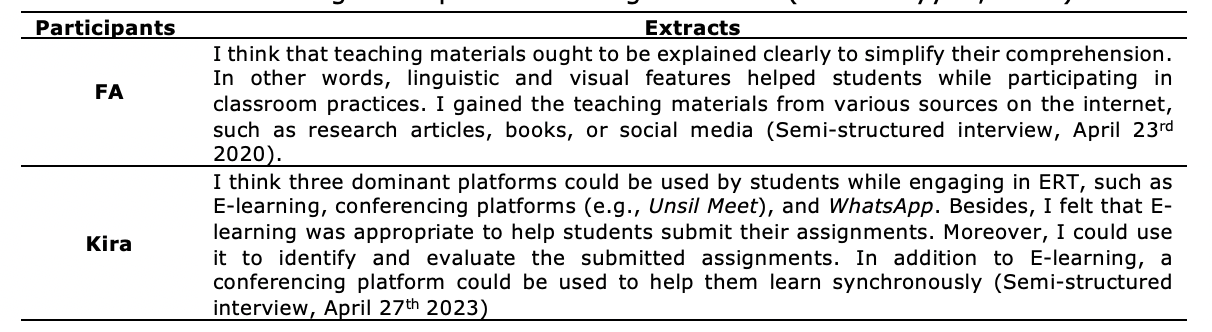

Applying proper teaching materials and instructional platforms during an Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) was a crucial aspect of performing ERT. This answers the first sub-research question (that is, what teaching strategies did the teachers apply to engage their students emotionally during ERT?) As an example, FA maintained that teaching materials should be expressed clearly to simplify their comprehension. In particular, he said that linguistic and visual features supported students while engaging in classroom activities. Generally, such teaching materials were obtained from the internet (e.g., research articles, books, or social media). Churchill (2017) argues that technology-based pedagogy (e.g., web-based pedagogy) enables both teachers and students to apply technological devices in their teaching and learning practices to optimize the efforts of reaching the expected learning outcomes (El-Sulukiyyah, 2021).

Table 1: Extracts about implementing proper teaching materials and instructional platforms during emergency remote teaching.

Kira mentioned three major platforms that could be utilized by students while participating in ERT, such as E-learning, conferencing platforms (e.g., Unsil Meet), and WhatsApp. Initially, he further explained that E-learning was employed to support students when submitting assignments. Besides, she claimed that teachers were also able to use it to identify and evaluate the submitted assignments. Another platform was a conferencing platform, a learning platform which allows students to learn synchronously in a virtual classroom. Through this platform, teachers can organize each meeting in real-time. Lastly, WhatsApp (e.g., WhatsApp group) is a social media-based learning community helping them to create a learning forum (Sakkir et al., 2021). This platform was aimed at supporting students to have a focus group discussion about a certain topic or phenomenon relevant to their teaching materials. LaBonte (2020) contends that teachers are expected to understand students' learning needs and help. Additionally, Khan (2016) adds that teachers should possess sufficient knowledge and ingrained practices in the e-learning framework, such as pedagogical, institutional, technological, management, interface design, ethics, resource support, and evaluation. Given these facts, teachers attempted to provide appropriate and effective teaching materials and instructional platforms facilitating students to learn and survive in ERT. The findings of this article are similar to those of the study conducted by Manca and Delfino (2021) who focused on how school clusters adapted to the students’ challenges during COVID-19 viewed from their reactions to the implemented school system and activities (e.g., participation, autonomy, motivation, and engagement). They inferred that the surveyed participants showed robust pre-existing digital competence, cooperative school community members, and a non-traumatic transition to online learning. Additionally, Gao (2020) studied Australian students' feelings about the problems and solutions during online learning of Chinese values of life. The similar notion of this study to the present research rests on the students' perceptions of ERT. The students argued that face-to-face and ERT activities were extremely dissimilar. To resolve this, Gao mentioned that applying proper teaching strategies and improved assessment requisites allowed students to engage in online classroom activities. Based on the similar concepts of this study to other previous ones, implementing a firm academic culture enabled both teachers and students to respond properly to a dynamic situation of ERT.

Actualizing tolerance-based learning activities

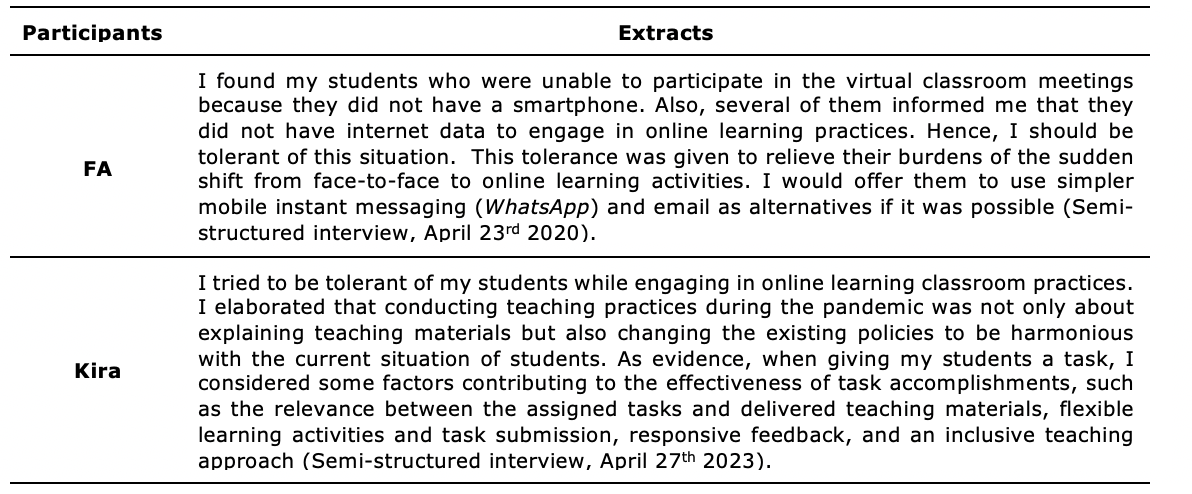

Tolerance-based learning activities are another activity used by teachers to maintain students' emotional engagement during ERT. This thematic finding responds to the first sub-research question (that is, what teaching strategies did the teachers apply to engage their students emotionally during ERT?). For instance, FA stated that he discovered some students who could not take part in the virtual classroom meetings since they did not have a smartphone. Some of them also reported that they did not have internet data to participate in online learning practices. In response to these problems, FA offered them a solution to help them engage in virtual classroom activities. He claimed that this tolerance was given to relieve their burdens of the sudden shift from face-to-face to online learning activities. More specifically, he contended that he may utilize simpler mobile instant messaging such as WhatsApp and email if it is possible to apply.

Table 2: Extracts about actualizing tolerance-based learning activities.

As evidenced in the excerpt above, Kira also indicated her tolerance with her students while engaging in online learning classroom activities. She explained that performing teaching activities during the pandemic was not only about delivering teaching materials but also about changing the existing policies to fit the current situation of students. To illustrate, when assigning tasks to students, she considered several factors that can affect the effectiveness of task accomplishments, such as the relevance between the assigned tasks and delivered teaching materials, flexible learning activities and task submission, responsive feedback, and an inclusive teaching approach. With this in mind, students are expected to have a more positive emotional engagement to facilitate them in attaining the intended learning outcomes. Wei (2014) maintained that recognizing factors influencing inter- and intra-students’ differences in language learning attitudes facilitates teachers to comprehend the social change process. Also, it enables us to understand them when reacting to such a social change viewed from a specific socio-psychological locale. Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) relate tolerance to empathy where it functions as 'the glue of the social world'. It means that teachers possessing good empathy can understand others' wishes, envisage their behaviour and identify their emotions (Dewaele & Wei, 2014; Yundayani et al. 2021). Additionally, language learning. Curelaru et al. (2022) argue that the learning practices of COVID-19 post-pandemic have changed students' learning attitudes and preferences to a more positive and less stressful classroom atmosphere since they have been allowed to engage in blended and face-to-face learning practices.

Performing self-adaptation to technology-enhanced language teaching

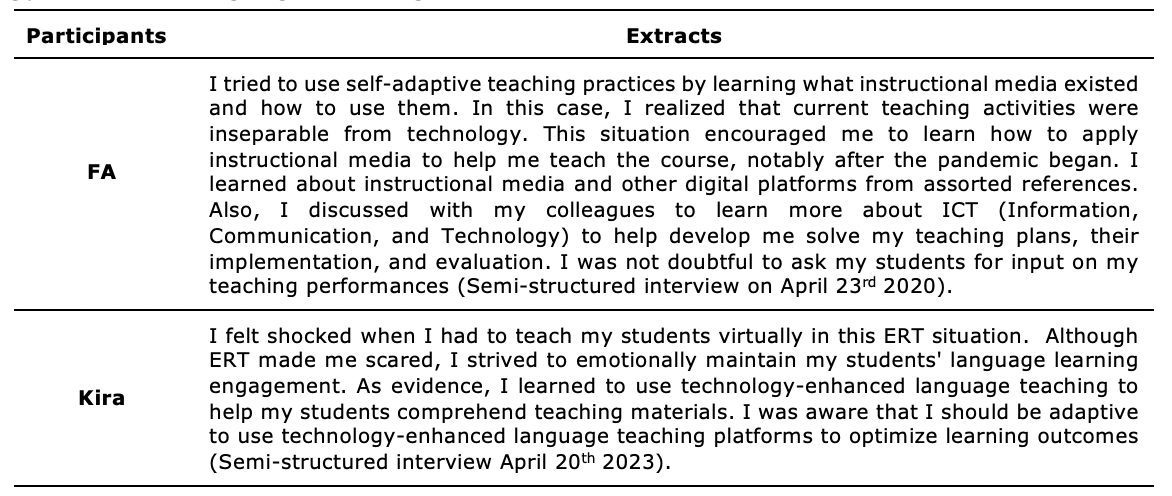

Self-adaptation is an appropriate and realistic attitude that could be undertaken by teachers during ERT. This finding addresses the second sub-research question (that is, how did teachers overcome their students’ challenges during learning in the ERT context?). Technology-based teaching challenges can be addressed gradually. For example, FA performed his self-adaptive teaching practices by learning what instructional media existed and how to utilize them. In other words, he was aware that current teaching practices could not be separated from technology. This situation motivated him to learn to apply such instructional media for teaching his course, especially after the pandemic began. He learned about instructional media and other digital platforms from miscellaneous literature. In addition, he also consulted a colleague who knows more about ICT (Information, Communication, and Technology) to help develop his entire plans, its implementation, and evaluation to make more use of technology. He was not reluctant to ask his students for input about his teaching to ensure that all went well. This attitude emerged because of his open-mindedness and open-heartedness to develop his limited technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK). Briefly stated FA was adaptive to technology-enhanced language teaching.

Table 3: Extracts about performing self-adaptation to technology-enhanced language teaching.

Likewise, Kira showed a similar attitude to ERT. As an illustration, although ERT scared her since it had to be conducted almost immediately, she strived to emotionally maintain her students’ language learning engagement. For example, she learned to apply technology-enhanced language teaching to help students understand teaching materials. She realized that she had to improvise to use such technology-enhanced language teaching platforms it had to be constantly adapted to the teachers and students to optimize learning and strengthen their ability related cultivating learning experiences (Granić, 2008). In addition, Verpoorten et al. (2009) hypothesized that successful personalization (adaptation) to e-learning technologies depends on three agents of education, namely the teacher, the students, and the machine.

The teachers' self-adaptive attitude enabled students to have improved learning motivation and positive language learning engagement. Besides, this self-adaptive attitude not only built a good rapport between teachers and students but also raised their awareness of the fact that successful teaching and learning processes do not only rely on teachers or students. Therefore, performing reciprocal and supportive teaching and learning practices allowed both teachers and students to reach their learning objectives.

Using contextualized teaching methods during emergency remote teaching

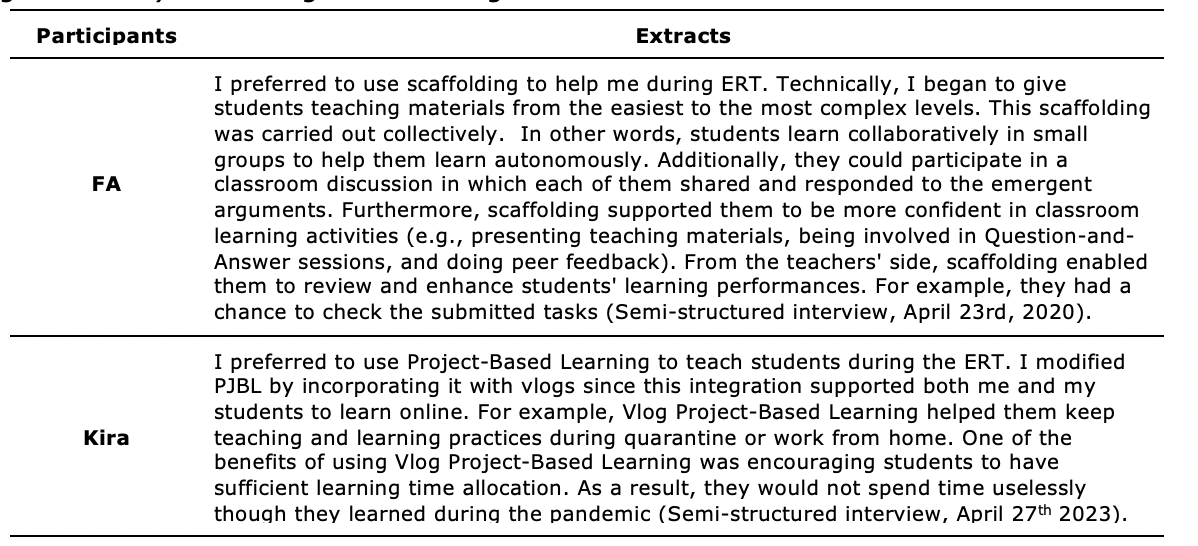

To maintain students’ emotional engagement during teaching and learning practices under ERT, teachers used contextualized teaching methods. This thematic finding focuses on the first sub-research question (that is, what teaching strategies did the teachers apply to engage their students emotionally during ERT?). To begin with, FA preferred to apply scaffolding to facilitate him during ERT. In practice, he started to provide students with teaching materials from the easiest to the most complex levels. This scaffolding was conducted collectively. It means that students learn collaboratively in small groups to enable them to learn autonomously. Besides, they could take part in a classroom discussion where each of them shared and responded to the emergent arguments. Moreover, scaffolding encouraged them to be more confident in classroom learning activities, such as presenting teaching materials, being involved in Question and Answer sessions, and doing peer feedback. From the teachers' side, scaffolding allowed them to review and improve students' learning performances. As an example, they had an opportunity to check assigned tasks. Wood et al. (1976) contended that scaffolding assists teachers in engaging students in the assigned tasks, reducing degrees of freedom, keeping goal orientation, evaluating critical task features, managing frustration and promoting problem-solving skills. Scaffolding can be implemented in various practices, such as bridging, contextualizing, schema building, re-presenting text, and developing metacognition (Walqui, 2006). Even though scaffolding offers valuable contributions to language teaching, it should be carried out properly. In this case, it should be conducted when students are ready to engage in the given tasks or directed learning activities. Additionally, it should be operationalized when their peers and teachers understand the targeted goals of learning (De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000; Walqui, 2006). By doing so, students would not regard those tasks as mere formalities.

To sum up, scaffolding not only offered a chance for students to adjust their learning strategies to fit an ERT situation but also empowered teachers to contextualize their teaching practices to the students' affective factors (e.g., emotions) influencing their learning success.

Table 4: Extracts about using contextualized teaching methods during emergency remote teaching

On the other hand, Kira preferred to utilize Project-Based Learning (hereafter, PJBL) to teach students during the ERT. In particular, she modified PJBL by integrating it with vlogs since this integration supported both her and her students to learn online. As an example, Vlog Project-Based Learning enables them to maintain teaching and learning practices during quarantine or work from home (WFH). One of the advantages of applying Vlog Project-Based Learning was allowing students to have sufficient learning time allocation. In other words, they would not spend time uselessly though they learned during the pandemic. The teacher herself had an opportunity to evaluate submitted Vlog Project-Based Learning tasks effectively due to adequate time allocation. Further, Vlog Project-Based Learning shaped students' learning autonomy because they collaborated with their peers virtually to accomplish the assigned project. Aligned with this, Andriani & Abdullah (2017) claimed that PJBL helps students enhance their cognition, work ethics, and interpersonal skills provoke their serious thinking processes, attain their linguistic competencies and performances, and maintain their identities as Non-Native speakers of English. Likewise, it allows students to engage in knowledge-gaining activities and skills training under the teachers' supervision (Kettanun, 2015). Further, it guides students to be autonomous learners (Jabu et al., 2021; Yagcioglu, 2015).

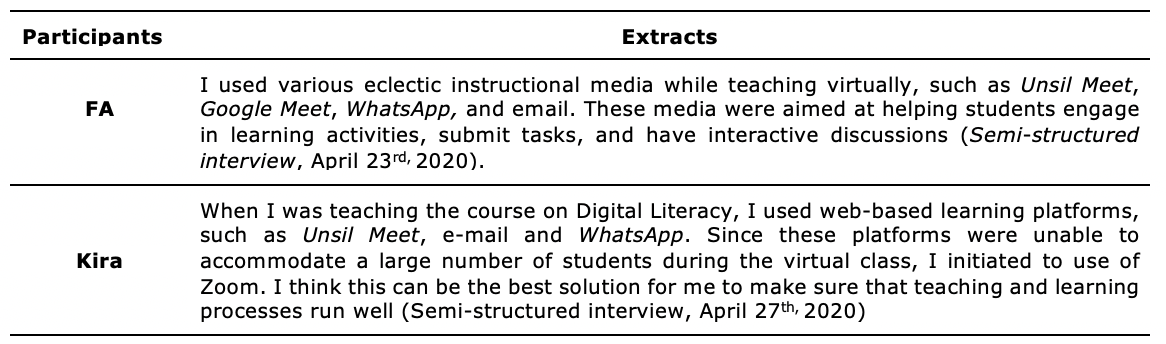

Applying eclectic instructional media during emergency remote teaching

Applying eclectic instructional media during an ERT remains inevitable. This thematic finding accentuates the second sub-research question (that is, how do teachers overcome their students’ challenges during learning in the ERT context?). In this case, FA utilized heterogeneous instructional media when teaching in his virtual classrooms, such as Unsil Meet, Google Meet, email, and WhatsApp. These instructional media were employed interchangeably depending on the classroom situations and students. As an example, he applied Unsil Meet and Google Meet when giving a lecture, conducting a discussion, or performing a classroom presentation. However, this utilization varied dynamically according to the quality of the internet connection. In addition, he also employed instructional media differently for each class, such as Unsil Meet for Class A and B and Google Meet for Class C. This distinct selection was based on the agreement between teachers and students. With this in mind, a democratic classroom atmosphere was established. Meanwhile, email was used for task submissions and was suggested for all classes. Additionally, he employed WhatsApp as a medium to communicate personally. This medium was also used as an alternative when other instructional media did not work properly.

Table 5: Extracts about applying eclectic instructional media during emergency remote teaching

In a similar vein, Kira made use of Unsil Meet, E-learning, and WhatsApp groups as the main instructional media during ERT. More specifically, she applied Unsil Meet when students were not too much in a virtual class. In the same way, saving internet data became a primary consideration of utilizing Unsil Meet as an instructional medium. She added that the use of Unsil Meet was more efficient than other digital platforms, notably Zoom. This effort represents her empathy for her students viewed from the financial aspect. As a result, students may feel appreciated since their aspirations and complaints were concretely responded to. Technically, she maintained that students did not need to send their video tasks because it tends to be excessive in terms of internet data use. Alternatively, she suggested her students upload their video tasks to their social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube, and share the links to the WhatsApp group. Next, she also made a regulation that the submitted tasks (video tasks) must not be more than 5 MB. Honebein and Sink (2012) assume that eclectic instructional design and media is an attempt to shape a learning experience from various learning theories and practices so that it fits the present situation and target situation of students (Andriani & Abdullah, 2017). Similarly, Farrington (2012) notes that eclectic instructional design is a model-independent process adjusted to the assorted instructional process model to meet the expected learning goals. Given these facts, students could have good motivation to emotionally engage in classroom activities, especially during ERT.

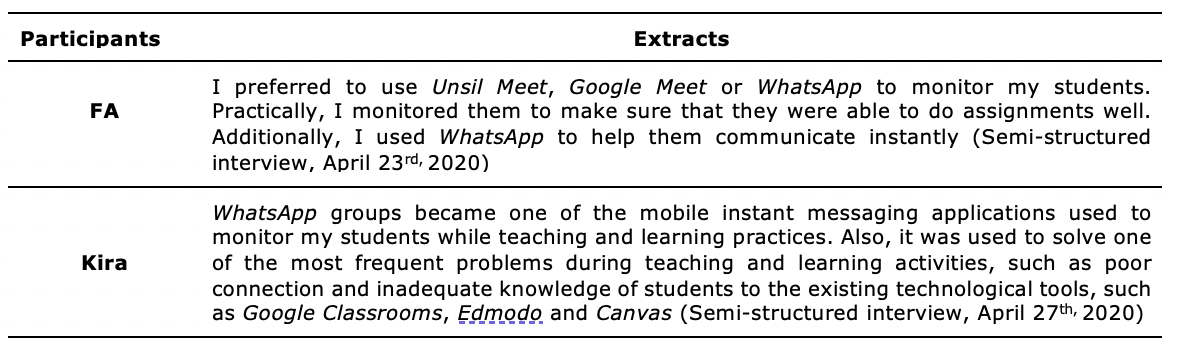

Utilizing constructive and humanizing online learning monitoring

Constructive online learning monitoring becomes another piece of empirical evidence in this study. This thematic finding lies in the second sub-research question (that is, how do teachers overcome their students’ challenges during learning in the ERT context?). To illustrate, FA stated that he exerted Unsil Meet, Google Meet, or WhatsApp as platforms to monitor his students in pre-activities, main activities, and post-activities of learning. These platforms were chosen based on the negotiation between teachers and students. Through these platforms, he could monitor the students' comprehension of conveyed teaching materials and proper learning activities and tasks. Al-Hattami (2019) explained that providing constructive feedback facilitates students to bridge the gap between the present and the expected learning performances. In other words, ideal teaching activities engage students' learning competencies and performances with the teachers' teaching approaches.

Table 6: Extracts about utilizing constructive and humanizing online learning monitoring

On the other hand, Kira preferred to use WhatsApp groups, Vlogs, E-learning, and cell phones as media to monitor her students' learning competencies and performances. For instance, she requested her students to utilize vlogs when they faced problems during learning practices. Vlogs and WhatsApp groups can be effective digital platforms allowing them to share what they experienced or encountered. If students still encountered obstacles while applying such platforms, she would have contacted her students by cellphone. This was carried out to resolve students' problems during online learning (e.g., out of internet data or poor internet connection). In particular, she would cooperate with class leaders to call absent students. In other words, a constructive and humanizing pedagogical approach implemented in online learning monitoring potentially enhances students' motivation to have better emotional learning engagement. Giroux (2010) asserted that pedagogy should showcase its meaningfulness and connection to social change by involving students in their world. Influential social change can be actualized by accommodating the learning needs of marginalized students.

In summary, utilizing constructive and humanizing online learning monitoring offers ongoing analysis and the ability to envisage pedagogical shifts in students' behaviour, network configuration, and pedagogical interventions constantly (Dawson, 2010). Teachers are expected to not only emphasize the effectiveness of how they deliver the teaching materials and reach the desired learning objectives but also how they respond to the student's learning activities constructively and humanely. When some students encounter difficulties in understanding the teaching materials and directions, teachers should view this as a natural process of learning. On the one hand, some students may be able to comprehend the delivered teaching materials and do the assigned tasks well. Additionally, they should familiarize themselves with digital platforms as a medium of instruction, particularly during online learning and monitoring.

Conclusion

This study examined how teachers maintained the students’ emotional engagement during Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT), especially in the Indonesian English as a foreign language (EFL) context. Six predominant thematic findings were used during ERT. They are (1) implementing proper teaching materials and instructional platforms, (2) actualizing tolerance-based learning activities, (3) performing self-adaptation to technology-enhanced language teaching, (4) employing contextualized teaching methods, (5) applying eclectic instructional media, and (6) utilizing constructive and humanizing online learning monitoring. These findings show that both teachers could maintain the students' emotional engagement during ERT. In particular, teachers were able to overcome their students’ challenges.

Practically speaking, the current study contributes to the teaching and learning practices in the higher education context. In particular, it provides practical information, notably for Teachers of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL), students, and policymakers to notice the importance of maintaining students' emotional engagement while performing teaching and learning activities during ERT. By doing so, effective and interactive classroom activities can be attained. Further, perceptual mismatches among teachers and students towards the essence of engaging in ERT could be avoided.

Although this study provides useful contributions to the importance of maintaining the cognitive engagement of students while learning online in the Indonesian context, it has some limitations. First, a rapid shift of teaching practices from the pandemic to the post-pandemic era has affected classroom activities. This situation indirectly influenced the contributions of the present study conducted during the pandemic. However, the notion of the significance of maintaining the students' cognitive engagement remains vital in post-pandemic learning activities. Therefore, future studies are expected to investigate the students' cognitive engagement in post-pandemic learning activities to explore how teachers adapt to the paradigmatic shift of teaching practices. Second, this study only utilized a single data collection technique to gather the data. Further studies can triangulate the data collection by using various techniques, such as observation, documentation and stimulated recall. Finally, the present study only emphasized the importance of cognitive engagement from the teachers’ perspectives and their teaching practices. Further studies are recommended to investigate it from the students’ perspectives.

References

Abdullah, F., Tandiana, S. T., & Saputra, Y. (2020). Learning multimodality through genre-based multimodal texts analysis: Listening to students’ voices. Vision: Journal for Language and Foreign Language Learning, 9(2), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.21580/vjv9i25406

Ahmed, A., Niaz, A., & Ikram Khan, A., (May 7th, 2020). Report on online teaching and learning amid COVID-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3646414

Aladsani, H. K. (2022). A narrative approach to university instructors' stories about promoting student Engagement during COVID-19 Emergency remote teaching in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1922958

Al-Hattami, A. A. (2019). The perception of students and faculty staff on the role of constructive feedback. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 885-894. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12157a

Anderson, L. (2020, 20 March). ‘Smiles are infectious’: What a school principal in China learned from going remote. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-03-20-smiles-areinfectious-what-a-school-principal-in-china-learned-fromgoing-remote

Andriani, A., & Abdullah, F. (2017). Invigorating the EFL students in acquiring new linguistic knowledge: Language learning through projects. In B. Bram, C. L. Anandari, M. Wulandari, M. E. Harendita, T. A. Pasaribu, Y. Veniranda, & Y. A. Iswandari (Eds.). Proceedings of the 4th International Language and Language Teaching Conference, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 3-4 November (pp.1-15). Sanata Dharma University Press. http://repositori.unsil.ac.id/7258/1/7.pdf

Baralt, M., Gurzynski-Weiss, L., & Kim, Y. (2016). Engagement with the language. In S. Sato & S. Ballinger (Eds.). Peer interaction and second language learning: Pedagogical potential and research agenda. (pp. 209-239). John Benjamins.

Baron-Cohen, S., & S. Wheelwright. (2004). The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 34(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jadd.0000022607.19833.00

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brazendale, K., Beets, M. W., Weaver, R. G., Pate, R. R., Turner-McGrievy, G. M., Kaczynski, A. T., Chandler, J. L., Bohnert, A., & von Hippel, P. T. (2017). Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: The structured days hypothesis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0555-2

Çakar, K., & Aykol, Ş. (2021). Case study as a research method in hospitality and tourism research: A systematic literature review (1974–2020). Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62(1), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965520971281

Carr, A. (2020). COVID-19, indigenous peoples, and tourism: A view from New Zealand. Tourism Geographies, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1768433

Chiu, T. K. F. (2021). Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(issue sup1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998

Churchill, D. (2017). Digital resources for learning. Springer.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Magni, P. A., & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Curelaru, M., Curelaru, V., & Cristea, M. (2022). Students’ perceptions of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative approach. Sustainability, 14(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138138

Dawson, S. (2010). ‘Seeing’ the learning community: An exploration of the development of a resource for monitoring online student networking. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(5), 736-752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00970.x

De Guerrero, M. C. G., & Villamil, O. S. (2000). Activating the ZPD: Mutual scaffolding in L2 peer revision. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 51-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00052

Dewaele, J.-M., & Wei, L. (2014). Attitudes towards code-switching among adult mono-and multilingual language users. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(3), 235-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.859687

Egbert, J. (2020). The new normal? A pandemic of task engagement in language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 314-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12452

Egbert, J., Shahrokni, S., Zhang, X., Abobaker, R., Bantawtook, P., He, H., Huh, K. (2019, November 20). Creating a model of language task engagement: Process and outcome [presentation]. Research Conversation, Washington State University-Pullman.

Farrington, J. (2012). A rose by any other name. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 25(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.20136

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement(pp. 763–782). Springer.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build a theory of positive emotions.American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gao, X. (2020). Australian students’ perceptions of the challenges and strategies for learning Chinese characters in emergency online teaching. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 1, 83-98.

Ghanizadeh, A., Amiri, A., & Jahedizadeh, S. (2020). Towards humanizing language teaching: Error treatment and EFL learners' cognitive, behavioural, emotional engagement, motivation, and language achievement. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 8(1), 129-149. https://doi.org/10.30466/ijltr.2020.120811

Giroux, H. A. (2010). Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy. Policy Futures in Education, 8(6), 715-721. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2010.8.6.715

Granić, A. (2008). Intelligent interfaces for technology-enhanced learning. In S. Pinder (Ed.). Advances in human-computer interaction(pp. 143-160). I-Tech.

Guan, Y., Deng, H., & Zhou, X. (2020). Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on career development: Insights from cultural psychology. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103438

Hasan, N. & Bao, Y. (2020). Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”, Children and Youth Services Review, 118.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355

Heigham, J., & Croker, R. A. (2009). Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., & Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review.

Honebein, P. C., & Sink, D. L. (2012). The practice of eclectic instructional design. Performance Improvement, 51(10), 26-31.https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21312

Hong, W., Zhen, R., Liu, R.-D., Wang, M.-T., Ding, Y., & Wang, J. (2020). The longitudinal linkages among Chinese children's behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement within a mathematics context. Educational Psychology, 40(6), 666-680. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1719981

Jabu, B., Abduh, A., & Rosmaladewi, R. (2021). Motivation and challenges of trainee translators participating in translation training.International Journal of Language Education, 5(1), 490-500. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v5i1.19625

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2008). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Kettanun, C. (2015). Project-based learning and its validity in a Thai EFL classroom. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 192, 567-573.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.094

Khan, B. H. (Ed.) (2016). Revolutionizing modern education through meaningful e-learning implementation. IGI Global.

King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of the text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 257–270). Sage.

Koenig, H. G. (2020). Ways of protecting religious older adults from the consequences of COVID-19. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.04.004

LaBonte, R. (2020, March 30). Emergency remote teaching: resources, tools, and ideas. CaneLearn. https://canelearn.net/emergency-remote-teaching

Ladd, G. W., Buhs, E. S., & Seid, M. (2000). Children’s initial sentiments about kindergarten: Is school liking an antecedent of early classroom participation and achievement? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46(2), 255–279. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/mpq/vol46/iss2/5

Luan, L., Hong, J.-C., Cao, M., Dong, Y., & Hou, X. (2020). Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: a structural equation model. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1855211

Manca, S., & Delfino, M. (2021). Adapting educational practices in emergency remote education: Continuity and change from a student perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1394-1413. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13098

Merriam, S. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

Murray, A. (2010). Empowering teachers through professional development. English Teaching Forum, 48(1), 2–11. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ914883.pdf

Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia (2020). Circular Number 4 of 2020 on Implementation of Education Policy in Emergency during COVID-19 Spread.

Osborne, J. W. (1997). Race and academic disidentification. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 728. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.728

Papadopoulou, S., & Vlachos, K. (2014). Using digital storytelling to develop foundational and new literacies. Research Papers in Language Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 235-258. https://rpltl.eap.gr/images/2014/05-01-235-Papadopoulou-Vlachos.pdf

Ramshe, M. H., Ghazanfari, M., & Ghonsooly, B. (2019). The role of personal best goals in EFL learners' behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement. International Journal of Instruction, 12(1), 1627-1638. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.121103a

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Sakkir, G., Dollah, S., Arsyad, S., & Ahmad, J. (2021). Need analysis for developing writing skill materials using Facebook for English undergraduate students. International Journal of Language Education, 5(1), 542-551. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v5i1.14856

Saputra, Y. (2018). Changing students' perception of learning extensive listening through YouTube. English Empower, 3(1), 41-49.https://www.ejournal.unitaspalembang.ac.id/index.php/eejll/article/view/65

Saputra, Y., & Fatimah, A. S. (2018). The use of TED and YouTube in the extensive listening course: Exploring possibilities of autonomy learning. Indonesian JELT, 13(1), 73-84. https://doi.org/10.25170/ijelt.v13i1.1451

Sciarra, D. T., & Seirup, H. J. (2008). The multidimensionality of school engagement and math achievement among racial groups.Professional School Counseling, 11(4), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801100402

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioural and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer.

Snelling, J., & Fingal, D. (2020, 16 March). 10 strategies for online learning during a coronavirus outbreak. [Blog] International Society for Technology in Education. https://iste.org/blog/10-strategies-for-online-learning-during-a-coronavirus-outbreak-2

Spiers, J. & Riley, R. (2019). Analyzing one dataset with two qualitative methods: the distress of general practitioners, a thematic and interpretative phenomenological analysis, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(2), 276-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1543099

Sukmawan, Lestari-Setyowati, & El-Sulukiyyah, A. A. (2021). The effect of authentic materials on writing performance across different levels of proficiency. International Journal of Language Education, 5(1), 515-527. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v5i1.15286

Trust, T. & Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/215995

Tzafilkou, K., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2021). Negative emotions, cognitive load, acceptance, and self-perceived learning outcome in emergency remote education during COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7497-7521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10604-1

Verpoorten, D., Petit, L., Castaigne, J-L., & Leclercq, D. (2009). Adaptivity and adaptation: which possible and desirable complementarities in a learning personalization process. In V. Hodgson, C. Jones, T. Kargidis, D. McConnell, S. Retalis, D. Stamatis, & M. Zenios (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Networked Learning 2009, Halkidiki, Greece, 5th-6th May. http://www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/past/nlc2008/abstracts/PDFs/Verpoorten_392-400.pdf

Voelkl, K. E. (1996). Measuring students' identification with school. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(5), 760-770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164496056005003

Walker, C. O., Greene, B. A., & Mansell, R. A. (2006). Identification with academics, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy as predictors of cognitive engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 16(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2005.06.004

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 159–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050608668639

Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes.Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging knowledge and identity in complementary classrooms for multilingual minority ethnic children. Classroom Discourse, 5(2), 158-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2014.893896

Whittle, C., Tiwari, S., Yan, S., & Williams, J. (2020). Emergency remote teaching environment: A conceptual framework for responsive online teaching in crises. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/ils-04-2020-0099

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 42. World Health Organization. Retrieved 10 November 2023 from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200302-sitrep-42-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=224c1add_2&download=true

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem-solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Yagcioglu, O. (2015). New approaches on learner autonomy in language learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 199, 428-435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.529

Yarrow, N. B., Masood, E., & Afkar, R. (2020, 27 October). Estimates of COVID-19 impacts on learning and earning in Indonesia: How to turn the tide. World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/184651597383628008/Main-Report

Yazzie-Mintz, E. (2009). Engaging the voices of students: A report on the 2007 & 2008 high school survey of student engagement. Centre for Evaluation and Education Policy, Indiana University.

Yin, R., K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Yundayani, A., Abdullah, F., Tandiana, S. T., & Sutrisno, B. (2021). Students' cognitive engagement during emergency remote teaching: Evidence from the Indonesian EFL milieu. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17(1), 17-33. https://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/2381/776