Introduction

A personal reflection on English language teaching scenarios in Thailand

Memories came flooding back to me when I started writing a statement of purpose to apply for a graduate school in the United States. Thoughts flashed back to my undergraduate years when I chaired the English Edutainment Club. During the preparation for a voluntary English camp for a school in a suburb of the northern part of Thailand, my professor who was a supervisor of the club told us:

One of the teachers at the school told me that students were curious why they were required to learn English because after graduation, they thought they had to help their parents to work on their own farms in that area where they would never meet any foreigners. Hence, we were supposed to design the tasks and activities that allowed them to see the opportunity to use English as much as possible. Though they insisted that they would never have a chance to meet any foreigners in their area, we’d better help them see that English could be important for them. For example, they might have to read the English information about the innovative agricultural technology and bring it to help improve their own farms in the future.

Although it was more than ten years ago, this vivid memory produced very clear, powerful, and detailed images in my mind. This experience revealed that a lacking relevance of the English lessons to students’ real lives seemed to be one of the most troublesome issues in Thai education. Moreover, my own experience in taking an undergraduate course entitled “Thai Life and Thought for English Teachers” was etched in my memory. This course was marvelous, for I relished learning and discussing a number of Thai elements in English such as Thai culture, value, tradition, architecture, myth, history, and so forth. I realized that for more than twelve years of learning English from kindergarten to university, I had never been trained to talk about my country and culture in English.

These stories shaped my thoughts on including Thai and other cultural elements in the English language education in Thailand as opposed to the exclusive preference given to the so-called standard British and American Englishes (Boonsuk & Ambele, 2021). I noticed that several English textbooks used by Thai English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers were found to prioritize the cultural content of native speakers (Keleş & Yazan, 2020; Thumvichit, 2018; Viengsang & Gajaseni, 2016). This situation was deemed problematic as it represented a pervasive cultural belief that cast doubt on the meaningful contributions of non-native speakers to the ELT teaching industry (Holliday, 2015). Moreover, a paucity of the elements relevant to Thai students in the English lessons resulted in failure to disclose Thai students’ identity to the world (Saemee & Nomnian, 2021). This situation also reflected the truth that Thai people perceived English as a sliding glass door that led to the other worlds but neglected to see themselves in that mirrored glass door in order to view its relationship to their own world.

In the EFL context of Thailand, English plays a pivotal role in major aspects of Thai people’s life such as economics, education, and ways of life. In reality, Thai people rarely use English in their daily lives, so most of them are struggling to learn English just to fulfil the university or school requirements. This fact definitely challenges a number of Thai EFL teachers to design the English communicative tasks that prepare Thai students for future competitive job markets (Sanpatchayapong, 2017). To do so, most of the Thai EFL teachers decide to use commercial English textbooks and other materials published by several well-known western publishers due to their simplicity of preparation and reliability of the target language (Ulla, 2019). Their lack of relevance and engagement to the target learners poses a real challenge to English language teachers who neglect the realities of the classroom (Tomlinson, 2015). More importantly, an absence of connection between English lessons and learners’ native language and culture causes a number of difficulties to the EFL learners to learn English such as a deficiency of motivation for learning English, and even a loss of national identity of the learners (Kanoksilapatham, 2018).

The essence of this connection piqued my interest in developing this autoethnographic study. My personal inclination toward autoethnography was due to the fact that I came up with the idea that understanding myself could be the initial step to understand others. I was enthused by autoethnography as it concentrates on the importance of researcher’s experience and deploy “writing about the self in contact with others to illuminate the many layers of human social, emotional, theoretical, political, and cultural praxis” (Poulos, 2021, p. 5). Besides, it is a powerful tool for inviting readers to understand the worlds of the autoethnographers and others connected to them (Chang, 2008). I also believed that my story might provide some insights and invite readers who share similar stories to compare, contrast, and find new dimensions of their own.

This study attempted to respond to the following research question:

How did I as a Thai EFL teacher establish a connection between the English lessons and the students’ real lives in the EFL classrooms in order to facilitate English language and literacy development of EFL undergraduate students at a public university in Thailand?

Literature Review

Conceptual framing to understand how connections can be established in the English language classrooms

To establish connections in the English language classrooms in Thailand may be beneficial to the learners as, they hardly use English in their daily lives. I found several attempts in literature that demonstrate how connections with EFL students may be established (He & Li, 2021; Kanoksilapatham, 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019; Kanoksilapatham & Suranakkharin, 2018, 2019, 2021; Lowe & Pinner, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2021). To understand this situation, I reviewed multiple theories including glocalization, culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy, and decolonization as follows.

Glocalization

The notion of glocalization was firstly used in the sense of business by Robertson (1995) to address the adaptation of multinational products and services to more specific local conditions; for example, some of the international brands reconstruct the menus based on the local tastes. With regard to English Language Teaching (ELT), Gray (2002) proposes the notion of glocalization as a way to provide learners with “a better fit and simultaneously connect the world of their students with the world of English” (p. 115). Supportively, Pawan and Pu (2019) explain that glocalization in relation to language teaching is the procedure for adjusting external and local pedagogical knowledge to classroom practices. Glocalized learning and teaching is pedagogically framed by the connection between local and global community vis-à-vis social responsibility, justice, and sustainability (Patel & Lynch, 2013). In addition, Higa (2017) reports that glocalization keeps balance between local and global perspectives, takes learners’ cognizance of their own cultures, and pays attention to the real-world issues outside of the classroom in order to eschew the ideology of English language superiority. From my point of view, I value the concept of glocalization for its object of shifting the emphasis onto the local. It reminds me of several Thai food products such as Thai congee topped with shredded chicken at McDonald’s and Thai green curry with fried chicken at KFC. These products show that these international companies try to modify their products to satisfy Thai people’s needs and sell them especially in Thailand. Similarly, I envision a possibility to glocalize the English lessons by incorporating the Thai local aspects into the English lessons. Consequently, I will be able to encourage my students to learn English in connection with “who they are, who they want to be, and whom they could become” (Kanoksilapatham & Suranakkharin, 2021, p. 1011).

Culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy

Grounded in the sociocultural learning theory, culturally responsive teaching (CRT) is defined as “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of culturally diverse students to make learning experiences more relevant to and effective for them” (Gay, 2010, p. 31). To put it more succinctly, CRT underscores the essence of the knowledge, skills, and cultural experiences that students from diverse backgrounds bring with them to school. Another intriguing instructional attempt that teachers make is to discover meaningful ways to relate the curriculum to the students by means of incorporating the students’ culture and life experiences to implement the curriculum and instruction (Taylor & Sobel, 2011). It can promote students’ motivation and engagement by means of providing the students with a meaningful context as well as conflating family customs, community culture and expectations with respect to upholding the values of their culture, knowledge, and experiences (Saifer et al., 2011). Specifically, Hollie (2013) proposes the notion of culturally and linguistically responsive (CLR) pedagogy that acknowledges the value of students’ cultural and linguistical backgrounds to inform and enrich the class. Simply put, CLR respects students’ home language and local cultures. When designing any tasks, instructional materials, and curricula, teachers, and other stakeholders are supposed to be mindful of the connection between the lessons and students’ home language and local culture. Thus, students will be able to acknowledge the value of their learning as they notice that the lessons are not far from their real lives. Also, they are willing to engage in the instructional activities that are meaningful to them. The bottom line is that in a conscious attempt to connect my students to the English lessons, it is imperative that I should pay attention to the concepts of CRT and CLR that similarly accentuate students’ home language, cultures, background knowledge, and prior experiences.

From glocalization to CLR, these theories are deemed necessary in terms of pinpointing how connections can be established in the English language classrooms. They share certain similarities in that they value students’ local culture, home language, and background knowledge that learners bring with them to the class by attempting to incorporate them into the lessons. Several empirical studies conducted by Thai scholars show the success in connecting what students brought to the English classrooms such as their local culture, tradition, and belief (Gajaseni, 2009; Inphoo & Nomnian, 2019; Kanoksilapatham, 2015, 2019; Kanoksilapatham & Channuan, 2018; Kongkaew, 2009; Rattanaphumma, 2006; Sawongta & Gajaseni, 2017; Ulla, 2019). However, little has been mentioned about the theories reviewed above. I found that most of the studies reveal that establishing connections between students’ home language and cultures to the English lessons yields positive results. To elaborate, the familiar learning context is capable of fulfilling the needs of the target learners more effectively.

Decolonization of English language pedagogy

Endeavors to decenter the western influences inherited from the native speakers of English and highlight the importance of the local knowledge, cultures, and educational needs mentioned above show the possibility of decolonizing ELT (Kumaravadivelu, 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2019). Decolonization refers to “the anti-imperialist political movement and to an emancipatory ideology which sought or claimed to liberate the nation and humanity itself” (Duara, 2004, p. 2). In the field of ELT, decolonization turns attention of the scholars to value the existence of the marginalized and attempts to decenter the age-old colonial stereotyped English pedagogy and materials (Macedo, 2019; Mishra & Bardhan, 2010). Since there is no colonial history of Thailand, the research literature relating to the decolonization issues regarding ELT in Thailand has become scarce (Insuwan, 2022; Methitham, 2011). However, the phenomenon regarding colonialism in ELT is ubiquitous. Evidently, Jindapitak and Teo (2011) disclose that ELT pedagogy in Thailand clings on the colonial linguistic ideology. Methitham (2011) also reveals some traits of linguistic and cultural imperialism including scholastic, linguistic, cultural, and economic aspects that are deemed to exist in ELT in Thailand. Based on this evidence, I acknowledge that ELT in Thailand is far from being apolitical because these characteristics seem to support and prolong imperialism. This situation might be a call for several Thai scholars to ponder over the notion of decolonizing ELT accordingly.

Autoethnographies in the field of English language teaching

Autoethnography is a qualitative research method that draws on and analyzes the lived experience of the author, brings cultural interpretation to the autobiographical data of the researcher, and connects the researcher’s insights to understanding self and its connection to others (Adams et al., 2015; Chang, 2008; Poulos, 2021). Autoethnography endeavors to empower ethnographers with a voice to represent “the other” of the research (Gannon, 2006). To decolonize these practices, the attention shifts onto investigating researchers’ experiences and the critical issues of the certain cultures in which they are situated (Yazan et al., 2021). Doing autoethnography goes beyond seeing ourselves in the mirror, but rather “it is about refracting our views both inward and outward as we use the relationship between the self and the world to understand the world and ourselves” (Orellana, 2020, p. 146).

In the field of English language teaching, autoethnography has received growing attention (Keleş, 2022; Yazan, 2019; Yazan et al., 2021). I have found that several scholars have used different types of autoethnography to study a variety of topics with regard to ELT. Canagarajah (2012) used autoethnography to explore his journey of English language teacher professionalization. Yazan (2019) investigated the use of a semester-long critical autoethnographic narrative of a teacher candidate in order to understand her identity negotiation and language ideologies. Liu (2020) used an autoethnographic inquiry to reflect on his recollections of English language teaching methodologies in China. Rose and Montakantiwong (2018) merged two autoethnographies into duoethnographies that juxtaposed two personal narratives in order to amplify the voices of two English language teachers from Japan and Thailand who deployed English as an International Language (EIL) pedagogy in their classes in two countries. Satienchayakorn and Sanpatchayapong (2022) utilized collaborative autoethnography to share their experiences and the lessons they learned as course developers and trainers for an English for Specific Purposes (ESP) course titled English for the Front Office. Satienchayakorn and Grant (2022) used collaborative autoethnography to share their voices and stories to understand the phenomenon of race and color in ELT in Thailand. Based on the reviewed literature, I recognized that autoethnography has proved to be an invaluable methodology for studying professional experiences in English language teaching accordingly.

Research Methodology

In this study, I chose to use a betweener autoethnography as a method of inquiry. According to Diversi and Moreira (2009), betweener is defined as “(un)conscious bodies experiencing life in and between two cultures” (p. 19). Betweener autoethnography lays particular stress on the spaces in-between us and them as the object of inquiry. It accounts for “how social sciences inquiry can use self-reflexivity, visceral knowledge, and authorial situatedness to advance scholarship that calls to, and hopes for, more inclusive imaginations of social justice” (Diversi & Moreira, 2018, p. 11). It attempts to examine, deconstruct, and represent the betweener bodies and experiences that encounter dehumanization, oppression, injustice, the classroom as a site for struggle, and the politics of exclusion of everyday life and knowledge production (Diversi & Moreira, 2015, 2017, 2018). Unlike other types of autoethnography, betweener autoethnography centers on the personal in connection with a critique of political issues embedded in the personal experiences. It allows one to envision a more inclusive interpretive community and socially just society by endeavoring to reduce the space between us and them, between inclusion and exclusion, between kindness and hatred, between joy and pain, between liberation and oppression (Diversi & Moreira, 2018). I perceive the English class as a site of struggle and seek justice for my students. Thus, betweener autoethnograhy seems to be a satisfactory alternative to investigate my (un)conscious lived experiences that link my culture with that of my students in relation to the political issues engraved in my stories.

In this study, I am a researcher, a participant of the study, and the topic of the exploration. I conducted this study and wrote my stories from the perspective of my personal world that is subjective awareness of myself as a Thai EFL teacher in a Thai university context and the holistic pattern of my personal teaching experiences. To perceive my world, I pondered over the overall pattern of personal life experiences vis-à-vis the aspects of self, the experience of self and world, and the ways in which experience and actions are organized. To do so, I needed to merge my biological flow, my social context, my bodily awareness, and my specific consciousness (Muncey, 2010).

Data collection

To collect the data, first of all, I recounted my past experiences by creating an autobiographical timeline with memorable events or experiences in the order that they occurred (Chang, 2008). I set out to use my memory as a way of reflecting on my personal and collective lived experiences. Although memory is not deemed to be a precise recollection, memory is a primary form of data for autoethnography as it is regarded as “a primary tool of human sense making and meaning making that helps us construct a coherent story of our lives” (Poulos, 2021, p. 27).

In the world of Harry Potter, the Pensieve is known as a magical tool used to review the stored memories. Owing to my inaccurate recollections, I endeavored to discover my own Pensieve that could help me unearth the entombed memories. Fortunately, I liked to put everything into my PowerPoint slides. That is to say, these slides represented my own lesson plans. Each slide could be a trip down memory lane that helped me recall what I did. Therefore, I decided to use my PowerPoint slides as the Pensieve that could navigate my way through my past experiences. After that, I visualized myself by combining the collection of my personal memory data through self-reflection. Specifically, I reflected on how I formed a relationship between the English lessons and students’ real lives. In addition to memory, I utilized the instructional artifacts including my PowerPoint slides and other supplementary materials I created to capture the past perspectives of my lived experiences.

Reflection

In August 2018, at a large public university in Pathum Thani province located in the central part of Thailand. At the Language Institute building on the fourth floor where my office was situated, I was about to finish my luncheon in a small pantry. While waiting to clean my silverware, my colleagues and I were envisioning what our class would look like on the first day of the semester. After a light-hearted banter with my colleagues, I went back to my room to prepare for the instructional materials. I put all my stuff into a black tote bag with the logo of the Language Institute on it. I thought I was ready for this semester. It was around 1:15 pm that I started walking from my office to the Social Sciences Building. It actually took me around five minutes to get there, but I saved the other 5-10 minutes to wait for the elevator and look for the room that I was going to teach. The class started at 1:30 pm. Today’s class was General English Part I. It was a course for all Thai first-year non-English major undergraduate students who were enrolled in the Thai program of all faculties. To study in this course, they were classified by particular English scores determined by the Language Institute and approved by the university committee. This course was open twice a year in the first semester and the summer of the academic year. Apart from being an instructor, in this semester, I was assigned to be a course coordinator, my regular job that I had to be accountable for every year since the second semester of my academic profession here. In this semester, there were more than 40 sections taught by more than 30 instructors that I had to monitor. Each section consisted of more than 32 students.

I carried a tote bag that contained a course book and a binder that included a list of students’ names and the course syllabus in my hand. This course book was an in-house instructional material created by a team of the faculty members of the Language Institute. That is to say, it was particularly tailor-made to serve the needs and interests of the students in this university. This book was used for the first time in this semester and aimed for having it on a trial basis before having it published by the university press in the next semester. The content of the book consists of eight chapters based on different themes that might pique students’ interests. Each chapter comprised all four skills of English including listening, speaking, reading, and writing, the language focus or the essential grammatical elements, key vocabulary, and communicative activities. It was photocopied and each paper was attached to the wire spiral. The course book was available at the copy centers around the Social Sciences Building. I also prepared some PowerPoint slides for the first unit. These are the examples of the PowerPoint slide, and the supplementary sheet I created for the first unit.

Figure 1: An example of the PowerPoint slide I created for the first unit.

Figure 1: An example of the PowerPoint slide I created for the first unit.

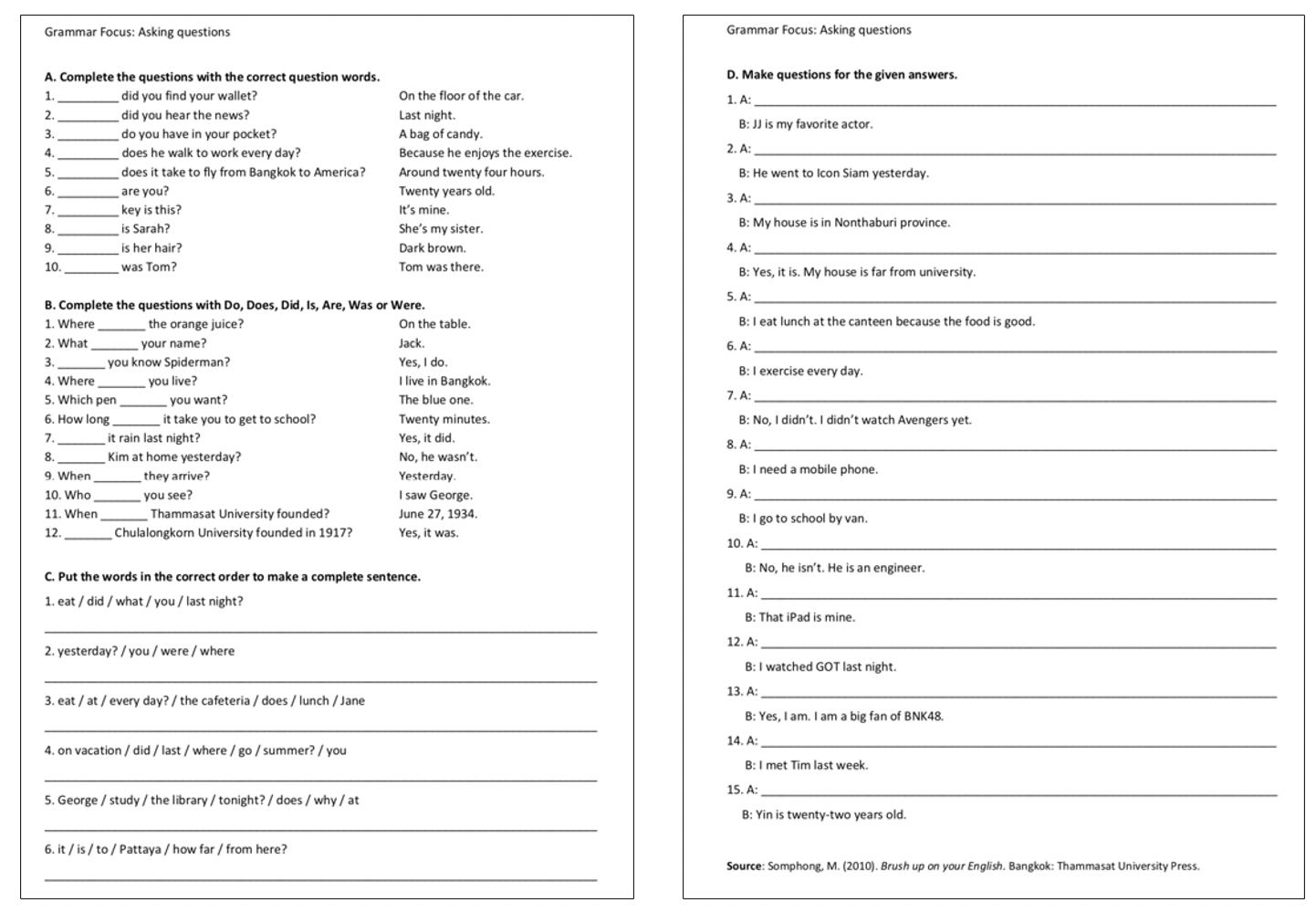

Figure 2: An example of the Supplementary Sheet I created for the first unit.

I used my personal memoir as a form of autoethnographic writing in order to reflect on my thoughts and highlight aspects of my life as a Thai EFL teacher who taught English to non-English major undergraduate students in a Thai public university during the year 2018. I wrote down my experiences and then incorporated in my story theories including glocalization, culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy, and decolonization. Then I presented my personal experience stories in the form of narratives with explanations in the hope that the readers might make sense of my words in the context of their own lives.

Data analysis

To unearth cultural understanding embedded in my stories, I used reflexivity known as rigorous self-reflection as an analytic lens to analyze the data by attempting to “identify and interrogate the intersections between self and social life” (Adams et al., 2022, p. 3). To be reflexive requires researchers to be constantly self-aware during the research process to expose knowledge production and gain insights on how this knowledge is constructed to affirm more precise analysis of the research (Pillow, 2003). According to Denzin (2018), reflexivity has “no fixed presence, no certain protocol, no set of practices that can produce it” (p. 240). Hence, I borrowed the mindful approach to ethnography from Orellana (2020) to demonstrate how I used reflexivity to analyze the data. She posited, “Slow it down. Step back. Sit with your data. Feel it. Listen more deeply” (p. 128). Speaking of which, I suspended my thoughts and judgement between what I saw and what I thought about what I saw. I moved my eyes slowly through the vignettes I chose to analyze. I slowly read them and examined my assumptions about what I thought, what happened, and what it meant. Therefore, I could listen more deeply to myself with my heart, balance my head with my heart, be open to what happened in the stories and what communicated the ideas. After that, I documented what I did, told it as a story, and put myself into it. Specifically, I allowed the readers to experience my process of coming to know what I looked for the answer to my research question. That is to say, I tried to unfold the messy processes behind discovering the truths to the readers. Moreover, I needed to be honest with myself and my readers by revealing my viewpoints, thoughts, and emotions.

Findings: The insights gained

My selected memories and cultural artefacts, which include my PowerPoint slides and some supplementary materials I created to supplement the English lessons, are presented as the following themes. These themes show how I endeavored to connect me as a Thai EFL teacher, the English lessons, the English classroom practices, and the instructional materials to the students’ world.

Theme 1: Acknowledging students’ home language

The following vignette shows the first theme that revolves around my acknowledgement of my students’ home language in the English class.

My story

It was the first week of the English foundation course for a group of Thai undergraduate students in the first semester of the academic year 2018 at a large public university in the central part of Thailand. This course was one of the two mandatory courses for all first-year undergraduate students who studied in Thai program. These students were enrolled in this course due to their English test scores obtained by either national or international standardized tests. Their English scores revealed that their level of English proficiency was quite low or intermediate. From my experience, some of them performed rather well in English. For instance, they could produce somewhat longer English sentences with a few grammatical errors and interact with me in English. In contrast, some could not read some of the English words such as determine, sometimes, discipline, etc. Also, some generated their own English words such as brung instead of brought, flung or fling instead of flew, etc.

I thought of providing them with the English exposure in the English classroom as much as possible because I knew that Thai students lacked enough English exposure outside of the classroom. Despite that, I did not formulate the English-only policy in my class. However, I was not aware of the students’ proficiency of English, so I neglected to ask my students if they understood what I was trying to communicate with them. I spoke English to introduce my students to several information such as the website of the language institute where they could gain access to the necessary resources of this course such as the course syllabus and other important announcement. While speaking in English, I heard the murmur of voices, but I could not recognize what that was. Hopefully, they might not be something negative. However, I did not neglect that mumble. My intuition told me not to ask what they said as I was afraid that they might feel embarrassed. Instead, I switched from English to Thai and explained more about what I just said and asked if there was anything they did not understand.

Reflection

After reviewing my recollection, I reflected on the reasons I decided to switch to my home language. Although I was not quite sure how I could interpret my students’ reactions, I assumed that they might not feel comfortable with what I was doing due to their weak English language proficiency backgrounds. In other words, my students’ English proficiency was a determining factor in my choice of language. I decided to switch from English to Thai to check if they were still able to connect with me. I did not want to disconnect them from the lesson by using just the language that was unfamiliar to them. My decision to switch from English to Thai rested on my opinion that I would not like to give some students a sense of being othered. I tried to be attentive to my students as much as I could, despite the challenge of dealing with a classroom size of thirty students. Although my decision to switch from English to Thai seemed to be in stark contrast to my intention to provide my students with exposure to English, the underlying reason for doing so was to check their understanding and connectedness with me. I did not cease speaking English, but occasionally switched to Thai. This situation showed that I adhered to my ideological standpoint within the framework of CLR pedagogy suggesting that an excessive use of an unfamiliar language might disconnect students from the lesson. Hence, my decision to generate an equivalency between my use of English and Thai might be able to establish a better connection between the English lesson to the world of my Thai students.

Theme 2: Adjusting the instructional materials to arouse students’ interest

The second theme that emerged from the narratives highlights how I interacted and utilized the instructional materials as the artifacts of this study in order to engage my students in the English lesson as illustrated in the following excerpt:

My story

In the next class, I began the English lesson by showing six pictures of the famous people on the big screen in front of the class and asking my students to match the pictures of the people with their names in order to activate their background knowledge before kicking off that day’s lesson entitled ‘The Famous People’. The PowerPoint slide contained the pictures and some information including the title, the instructions, and the names of the famous people. This slide consisted of the same content as what appeared in the students’ coursebook, except for the colorful pictures since they were printed in black and white. This coursebook was locally produced by a group of Thai faculty members of the language institute.

The pictures on the slide consisted of GOT 7 (a South Korean boy band), Taylor Swift (an American singer), Elon Musk (a business magnate), Black Pink (a South Korean girl group), Chris Evans (an American actor), and Ed Sheeran (a British singer). They were famous singers, actors, and business magnate whose faces were familiar to a number of Thai students.

After pressing the next button on the presentation clicker and the slide appeared on the screen, before I started saying anything, I noticed some of the positive reaction of my students while they were looking at the pictures of their favorite persons. Some of the female students nudged each other and pointed at the picture. Somebody blurted out, “GOT SEVEN!!” “BAMBAM!! (one of the members of GOT 7 whose nationality is Thai)” During that time, I noticed that their eyes sparkled while beaming at the picture of their favorite boy band. It was observable that most of the female students overtly reacted to these pictures; however, plenty of male students in an unreadable manner maintained a poker face even though there was a picture of Black Pink, one of the most popular Korean girl groups among Thai men shown on the screen.

“Ok, everyone. I would like you to look at these pictures on the screen,” I started talking to my students in English while beaming the laser pointer from the presentation clicker to those pictures. “I’m really sorry that the pictures in your book are black and white. So, please look at these beautiful and colored pictures on the screen instead. Could you please help me match the pictures with their names? Do you know who they are? Right?”

My students obviously understood what I told them and responded to my question instantaneously. It did not mean that everybody chorally said ‘YES’, but through their gesture, some nodded their heads. It was implied that they understood.

“For the first picture, do you know who they are?” I asked while beaming the laser pointer to the first picture. “GOT SEVEN,” some voices rose from several students. “Next, who are they?” I heard a louder voice when my laser pointer was beamed to the second and following pictures. I found that my students collaborated in this activity very well by speaking each name out loud although not every student spoke up. Their responses to the pictures demonstrated that these recognizable and familiar pictures and names might gradually help my students become acclimatized to the English lesson because they probably noticed that their teacher did not scare them with a number of alien alphabets on the screen.

Reflection

At this point in the narrative, it appears that I attempted to use the instructional materials including the pictures of the famous persons familiar to several Thai students to activate their background knowledge before starting the lesson. This I believe could help connect them to the English lesson and reduce the tension they brought to the class. Although the use of these pictures was not my original idea as they were a part of the textbook, I made them more interesting by bringing up their colorful version on the big screen to gain more attention from my students. Based on my observation, most of the students came to the English class with lower intermediate level of English proficiency, low motivation, and high anxiety over learning English. These students just entered university. They probably envisioned that learning English at the university might be intimidating. This perspective might initially bring about the demoralizing effect to these students. In my experience, some students were shaking like a leaf when I asked them to speak English with me. Some almost cried when they needed to speak English in front of the class. I regularly needed to ask them to breathe deeply to quell their stress and anxiety. Some of them told me that they had never spoken English or written a long paragraph in English despite twelve years of studying English in school. Somebody said they had never learned anything outside of the coursebook. Some added that they had never worked in groups or made presentations; their teachers usually gave them some worksheets that contained English grammar and vocabulary exercises to fill out. In addition, some told me that their teachers often criticized them for their inability to pronounce the English words as well as native speakers. All the information came from the informal conversation. Personally, I believed that there might be more stories of my students that led to their negative attitude towards learning English.

I thought that it might be a distressing experience for me if I knew that my lesson and I triggered some of their emotional trauma, so I tried to redesign the instructional materials to make it appropriate for my students. Actually, what I did was not different than what other experienced teachers around the world did in their classes. However, my intention to narrate this story relied on my intention to understand what I actually did in my class to connect my students to the English lessons. I hope that I might learn something from my ordinary experiences.

In reality, not every student overtly showed their interaction such as a group of the male students whose expression was unreadable. Hence, I was unable to deduce that the interaction of the students who blurted out the name of their favorite persons as well as their gestures such as nudging each other, pointing and beaming at the pictures signified a success of using this instructional material. But, hope springs eternal. This mundane detail of my experience could be a window to understand my feelings of using these instructional materials. That is to say, my students’ reaction to the materials satisfied my aspirations as I thought that at least, I could engage my students’ interest. This experience taught me that my efforts to devise these materials might not be in vain. Although the use of these pictures as the instructional materials did not come from my original thought, my attempt to present the colorful version of these pictures might be able to connect my students to the lesson more rapidly. Like what I mentioned at the end of the excerpt, I did not want to bombard my students with dense English alphabets on the big screen. Moreover, the use of the PowerPoint slide that contained similar content to what was in the students’ textbook might be able to help my students follow the lesson more easily. As a result, the use of the instructional materials that seem relevant to the students’ world might be able to create a sense of familiarity and comfort to the English lesson.

In addition, the response of the students to the pictures by naming each picture out loud showed that my students also endeavored to participate in the class by getting involved in the activity. That is to say, not only did I try to connect the English lesson to my students, but also my students themselves attempted to engage with the English lesson.

Last but not least, it was observable that the word GOT7 was mentioned several times in the story because most of the reactions I noticed came from a group of female students who might be big fans of this Korean boy band. It signified that GOT7 became relevant to a particular group of students in this class. Although other names were not mentioned in the excerpt, my students actually knew them as the correct responses to the pictures. It shows that they knew all of the persons in the pictures. However, it was possible that they might not be big fans of the others, or the big fans of the rest simply did not want to show their feelings.

Theme 3: Glocalizing the English language teaching materials

The final theme in the narrative presents my endeavor to create my own instructional materials based on the concept of glocalization as presented in the following excerpt.

My story

These slides were some of the instructional materials that I used in my class in order to teach the grammatical point namely comparative and superlative adjectives to my undergraduate students in the English foundation course. I did not just pick the sample sentences from the textbook to be presented on the slides; however, I myself created the sample sentences based on the pictures I googled online. I decided not to show just the sample sentences on the slides to explain this grammatical point. Instead, I would rather present the sample sentences along with the pictures in the hope that they might help instantiate the meanings of these sentences. In other words, I thought that the pictures might enable students to make more sense of how the focused grammatical point functioned in the sentences. To prepare for these slides, I googled the pictures based on the current trend among Thai teenagers or Thai society during that time such as the latest Thai and international blockbusters, the well-known local and international actors, singers, influencers, and so on. For example, the following slide (Figure 3) shows the picture of two leading characters from the famous Thai motion picture titled ‘Bad Genius’. Based on the movie, these two persons namely Lin (the woman on the left) and Bank (the man on the right) were the straight-A students who fabricated the exam-cheating scheme in order to earn money. Therefore, I created the sentence to explain that both of them were equally astute.

Note. [Photograph of the main characters in the Thai motion picture titled Bad Genius]. (n.d.). https://themomentum.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/unnamed-3-4-1280x720.jpg

Figure 3: PowerPoint slide I created to teach comparative adjectives

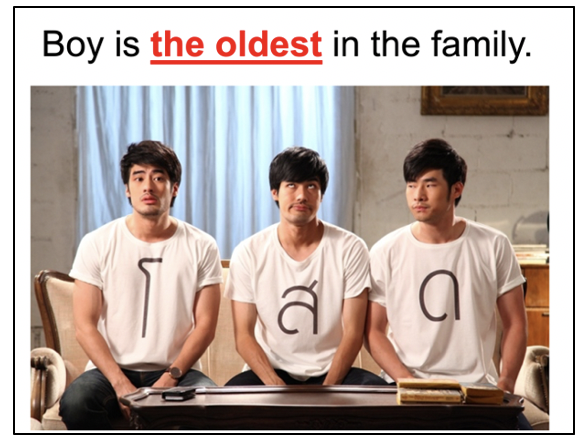

The other slide (Figure 4) shows the picture of three well-known Thai actors who are siblings whose names are Boy, Nong, and Pat respectively. The person on the left whose name is Boy is the oldest and most popular in the family. I thought this picture was apparent to teach the superlative adjective seeing that students would be able to make sense of using superlative adjective to compare three or more objects or persons through a number of people appearing in the picture.

Note. [Photograph of three well-known Thai actors who are siblings]. (n.d.).

https://music.mthai.com/news/newsmusic/168940.html

Figure 4: PowerPoint slide I created to teach superlative adjectives

Reflection

The essential point that I found from the above narrative together with the artifacts can be elaborated as follows. First, the PowerPoint slide comprises an English sentence as well as a picture. According to the first picture, two characters from the famous Thai motion picture were placed side by side. Noticeably, the sample sentence above the picture is talking about these two characters. Specifically, these two persons are compared. The students who watched this movie already might be able to connect the picture with the sentence instantaneously. Nevertheless, those who had not yet watched it might have felt a little lost unless I disclosed who Lin and Bank were. In fact, stereotypically, Thai students can associate Bank with the male and Lin with the female as these two names are common among Thai people. Though the meaning of the sentence might arouse the curiosity of those who did not yet watch the movie about the reason why these two characters were said to be equally intelligent and what happened with them in the movie, a paucity of the details of the story does not seem to hinder the students’ understanding of the sentence as the intention of the sentence is to just show how to make a comparison between two things that are the same in degree.

For the second picture, those who could recognize these three men might be able to understand the sentence instantaneously. However, the inability to acknowledge these three men did not seem to obstruct the students’ comprehensibility of the sentence since the intention of the sentence was to introduce how to say in English who had lived for a very longer time when compared to all of the three persons. The picture of three men is clear enough to explicate that superlative adjective is used to compare three or more things.

What’s more, the pictures in these two slides might be instantly recognizable to a lot of students as they were able to see these faces on several types of media in Thailand during the time that I created and used them in the class. To elaborate, the first picture came from the renowned Thai film that had been released during that time, whereas the second picture contained three well-known actors who starred in some of the Thai TV series that were on the air during the same time.

The creation of these slides was predicated on my thought that in lieu of using a hamburger as an example, I chose pad thai, a Thai dish that might look closer to the world of my students. Not unlike the way of glocalizing the products of the international companies to better fit the local taste (Robertson, 1995), the fabrication of these slides reveals my attempts to glocalize the English instructional materials to link with Thai students’ world, not to mention attracting their attention and facilitating their understanding of the English lessons accordingly.

Discussion: What can I learn from my stories?

The first lesson from my own narratives shows the essence of acknowledging students’ home language in the English class as well as striking a balance between students’ home language and their target language. My attempt in doing so is aligned with the notion of CLR that provides students with “positive environment that is conducive to learning and enables them to function optimally” (Hollie, 2013, p. 50). Moreover, the respect for students’ home language contributes to a caring and welcoming message that is liable to coax students into engaging in learning (Lucas & Villegas, 2010). However, several Thai scholars argue that students’ lack of enough exposure to English obstructs the success in learning English of Thai students, so they suggest that the use of Thai language to teach English be minimized (Akkakoson, 2016; Choomthong, 2014; Jindapitak & Teo, 2012). Nevertheless, based on my recollections, achieving a balance between home language and target language is essential, for no one culture and language should be superior to another (Kalantzis et al., 2016).

Another integral lesson drawn from these stories is the importance of instructional materials that have a powerful influence on students’ success in learning. Supportively, the instructional resources that are relevant and highly interesting plus the fact that the teachers acknowledge the realities of the classrooms and the importance of learners’ attitudes and learning preferences can facilitate students’ engagement in the learning process (Hollie, 2013; Tomlinson, 2012, 2016). When teachers are trying to adjust and glocalize ELT materials, they are creating a possibility to make a connection between the world of English and the world of students (Gray, 2002).

A final lesson is a call for decolonizing ELT in Thailand. Although Thailand was not colonized by any western countries, the spread of English empowered by two mainstream countries including the UK and the US undergirds and prolonged imperialism in the ELT industry (Methitham, 2011; Pennycook, 2000). Establishing connections in the English classrooms apparently demystifies the issue of decolonizing ELT in Thai context. It presents an attempt to reconceptualize and decenter ELT by downgrading the supremacy of ideologies about ‘native speakers’ of English. Embracing locality in lieu of advocating a mere exposure to imperialist and western ideologies could be a possible way to decolonize ELT, liberate Thai students from restrictive ideologies, and value their local identities.

Conclusion

My personal narratives reveal that establishing connections in the English classrooms of Thailand is not deemed to be far-fetched. Based on my stories, I have perceived the English classroom as a site of struggle, for it provides the unjust phenomenon to Thai students who strive to learn English but seldom use it in their daily lives. Hence, a number of Thai students are barely able to find a connection between English and their lives notwithstanding that EFL teachers have made a determined effort to inform them about the advantages of English. In light of this situation, students are often disconnected from the English class and experience a feeling of being othered. Moreover, a paucity of connection reveals a massive investment in the western ideologies and the devaluation of the local scholarship and wisdom. It demonstrates how inequalities occur in the English classroom. The emerging themes reveal my endeavors to prevent Thai students from being othered in the English classroom. Speaking of which, attempting to dismantle the imperialist, whiteness, and western ideologies as well as preserving locality seem to be the possible ways to connect Thai students to the English lessons. This situation should be a mighty wake-up call for decolonizing ELT in Thailand to emancipate Thai students from having been influenced by the power of imperialism that has been perpetuated in Thailand for a long time. All in all, my stories invite Thai EFL teachers and readers to reconsider the influence of colonialism over ELT that explicitly challenges the status quo. At the same time, they aim to portray a racial pedagogical change in Thai education. Besides, they might be a promising new avenue for Thai teachers and researchers to be cognizant of their own experiences. They also provide an alternative point of view and promising new ways of knowing and being. Last but not least, they offer a possibility to create a utopian space where we can experience a politics of hope and disrupt the status quo stemming from colonial vestiges.

References

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2015). Autoethnography: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2022). Introduction: Making sense and taking action: Creating a caring community of autoethnographers. In T. E. Adams, S. H. Jones, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (2nd ed., pp. 1-19). Routledge.

Akkakoson, S. (2016). Speaking anxiety in English conversation classrooms among Thai students. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 13(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2016.13.1.4

Boonsuk, Y., & Ambelle, E. A. (2021). Existing EFL pedagogies in Thai higher education: Views from Thai university lecturers. Arab World English Journal, 12(2), 125-141. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no2.9

Canagarajah, A. S. (2012). Teacher development in a global profession: An autoethnography. TESOL Quarterly, 46(2), 258-279. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.18

Chang, H. (2008). Autoethnography as method. Left Coast Press.

Choomthong, D. (2014). Preparing Thai students’ English for the ASEAN Economic Community: Some pedagogical implications and trends. Language Education and Acquisition Research Network (LEARN) Journal, 7(1), 45-57. https://so04.tc-thaijo.org/index.php/LEARN/article/view/102706/82253

Denzin, N. K. (2018). Performance autoethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Diversi, M., & Moreira, C. (2009). Betweener talk: Decolonizing knowledge production, pedagogy, and praxis. Routledge.

Diversi, M., & Moreira, C. (2015). Performing betweener autoethnographies against persistent Us/Them essentializing: Leaning on a Freirean pedagogy of hope. Qualitative Inquiry, 22(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415617208

Diversi, M., & Moreira, C. (2017). Autoethnography manifesto. International Review of Qualitative Research, 10(1), 39-43. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2017.10.1.39

Diversi, M., & Moreira, C. (2018). Betweener autoethnographies: A path towards social justice. Routledge.

Duara, P. (2004). Introduction: The decolonization of Asia and Africa in the twentieth century. In P. Duara (Ed.), Decolonization: Perspectives from now and then (pp. 1-18). Routledge.

Gajaseni, C. (2009). A development of English knowledge about Thai culture, ability to transfer knowledge, and attitude towards organizing English language learning about Thai culture by transferring knowledge to real life situations. [Unpublished manuscript]. Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

Gannon, S. (2006). The (im)possibilities of writing the self-writing: French poststructural theory and autoethnography. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 6(4), 474-495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708605285734

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teacher College Press.

Gray, J. (2002). The global coursebook in English language teaching. In D. Black & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching (pp. 105-115). Routledge.

He, D., & Li, D. CS. (2021). Glocalizing ELT reform in China: A perspective from the use of English in the workplace. RELC Journal, 54(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882211018499

Higa, M. (2017). English or Englishes? Glocalisation of English language teaching in Okinawa as expanding circle. Essex Student Journal, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5526/esj21

Holliday, A. (2015). Native-speakerism: Taking the concept forward and achieving cultural belief. In A. Swan, P. Aboshiha, & A. Holliday (Eds.), (En)countering native-speakerism: Global perspectives (pp. 11-25). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hollie, S. (2013). Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning. Shell Education.

Inphoo, P., & Nomnian, S. (2019). Dramatizing a northeastern Thai folklore to lessen high school students’ communication anxiety.PASAA, 57, 33-66. https://www.culi.chula.ac.th/Images/asset/pasaa_journal/file-10-134-xupv4c677263.pdf

Insuwan, C. (2022). The reconceptualization of learning English between native and non-native English-speaking teachers through the lenses of post-colonialism for EMI policy in Thailand. Manutsayasat Wichakan, 20(1), 367-380. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/abc/article/view/241700

Jindapitak, N., & Teo, A. (2011). Linguistic and cultural imperialism in English language education in Thailand. Journal of Liberal Arts Prince of Songkla University, 3(2), 10-29. https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/journal-la/article/view/64759/53112

Jindapitak, N., & Teo, A. (2012). Thai tertiary English majors’ attitudes towards and awareness of world Englishes. Journal of Studies in the English Language, 7, 74-116. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jsel/article/view/21921

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2016). Literacies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Kanoksilapatham, B. (2015). Developing young learners’ local culture awareness and global English: Integrated instruction. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 5(9), 676-682. https://www.doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2015.V5.591

Kanoksilapatham, B. (2016). Promoting global English while forging young northeastern Thai learners’ identity. 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 22(3), 127-140. http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2016-2203-09

Kanoksilapatham, B. (2018). Local context-based English lessons: Forging northern Thai knowledge, fostering English vocabulary. 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 24(2), 127-142. http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2018-2402-10

Kanoksilapatham, B. (2019). Constructing local Thainess-based English teaching materials: Southern Thailand. International Journal of Languages, Literature, and Linguistics, 5(4), 241-246. http://doi.org/10.18178/IJLLL.2019.5.4.235

Kanoksilapatham, B., & Channuan, P. (2018). EFL learners’ and teachers’ positive attitudes towards local community based instruction.Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(3), 504-514. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i3.9790

Kanoksilapatham, B., & Suranakkharin, T. (2018). Celebrating local, going global: Use of northern Thainess-based English lessons. The Journal of AsiaTEFL, 15(2), 257-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2018.15.2.3.292

Kanoksilapatham, B., & Suranakkharin, T. (2019). Tour guide simulation: A task-based learning activity to enhance young Thai learners’ English. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 16(2), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2019.16.2.1

Kanoksilapatham, B., & Suranakkharin, T. (2021). Enhancing Thai elementary students’ English and maintaining Thainess using localized materials: Two putative confronting forces. Studies in English Language and Education, 8(3), 1006-1025. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v8i3.19988

Keleş, U. (2022). Autoethnography as a recent methodology in applied linguistics: A methodological review. The Qualitative Report, 27(2), 448-474. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5131

Keleş, U., & Yazan, B. (2020). Representation of cultures and communities in a global ELT textbook: A diachronic content analysis.Language Teaching Research, 27(5), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362168820976922

Kongkaew, P. (2009). Effects of English language instruction of English for little guides in Krabi course on communication skills of grade 6 students [Unpublished master’s thesis], Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. https://portal.edu.chula.ac.th/pub/tefl/images/phocadownload/thesis/2009/pratchawan_ko_2009.pdf

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). A postmethod perspective on English language teaching. World Englishes, 22(4), 539-550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2003.00317.x

Liu, W. (2020). Language teaching methodology as a lived experience: An autoethnography from China. RELC Journal, 53(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220920371

Lowe, R. J., & Pinner, R. (2016). Finding the connections between native-speakerism and authenticity. Applied Linguistics Review, 7(1), 27-52. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-0002

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2010). The missing piece in teacher education: The preparation of linguistically responsive teachers. Teachers College Record, 112(14). https://doi.org/10.1177%2F016146811011201402

Macedo, D. (2019). Rupturing the yoke of colonialism in foreign language education: An introduction. In D. Macedo (Ed.), Decolonizing foreign language education: The misteaching of English and other imperial languages (pp. 1-49). Routledge.

Methitham, P. (2011). A modern-day Trojan horse: The political discourses of English language teaching. Journal of Humanities (Naresuan University), 8(1), 13-30.

Mishra, P., & Bardhan, S. K. (2010). Decolonizing English teaching and studies in India: Need to review classroom practices and teaching material. Journal of Teaching and Research in English Literature (JTREL), 1(4), 9-14.

Muncey, T. (2010). Creating autoethnographies. Sage.

Nguyen, T. T. M., Marlina, R., & Cao, T. H. P. (2021). How well do ELT textbooks prepare students to use English in global contexts? An evaluation of the Vietnamese English textbooks from an English as an international language (EIL) perspective. Asian Englishes, 23(2), 184-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2020.1717794

Orellana, M. E. F. (2020). Mindful ethnography: Mind, heart and activity for transformative social research. Routledge.

Patel, F., & Lynch, H. (2013). Glocalization as an alternative to internationalization in higher education: Embedding positive glocal learning perspectives. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 25(2), 223-230. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016539.pdf

Pawan, F., & Pu, H. (2019). Methods as interpretation and glocalization, not application: Water far away will not put out nearby fires. TESL-EJ, 22(4), 1-17. http://tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej88/a7.pdf

Pennycook, A. (2000). English in the world/the world in English. In A. Burns & C. Coffin (Eds.), Analysing English in a global context: A reader (pp. 78-89). Routledge.

Pillow, W. S. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000060635

Poulos, C. N. (2021). Essentials of autoethnography. American Psychological Association.

Rattanaphumma, R. (2006). A development of community-based English course to enhance English language skills and local cultural knowledge for undergraduate students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Robertson, R. (1995). Glocalization: Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Roberson (Eds.),Global Modernities (pp. 25-44). Sage.

Rodrigues, W., Albuquerque, F. E., & Miller, M. (2019). Decolonizing English language teaching for Brazilian indigenous peoples. Educação & Realidade, 44(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2175-623681725

Rose, H., & Montakantiwong, A. (2018). A tale of two teachers: A duoethnography of the realistic and idealistic successes and failures of teaching English as an international language. RELC Journal, 49(1), 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217746206

Saemee, K., & Nomnian, S. (2021). Cultural representations in ELT textbooks used in a multicultural school. rEFLections, 28(1), 107-120. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/reflections/article/view/251027/170161

Saifer, S., Edwards, K., Ellis, D., Ko, L., & Stuczynski, A. (2011). Culturally responsive standards-based teaching: Classroom to community and back (2nd ed.). Corwin.

Sanpatchayapong, U. (2017). Development of tertiary English education in Thailand. In E. S. Park & B. Spolsky (Eds.), English education at the tertiary level in Asia: From policy to practice (pp. 168-182). Routledge.

Satienchayakorn, N., & Grant, R. (2022). (Re)contextualizing English language teaching in Thailand to address racialized and ‘Othered’ inequalities in ELT. Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 36(1), 39-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2022.2044841

Satienchayakorn, N., & Sanpatchayapong, U. (2022). Collaborative autoethnography: A case as course developers and trainers for English for the front office. ThaiTESOL Journal, 34(1), 45-70. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/thaitesoljournal/article/view/256633/173279

Sawongta, W., & Gajaseni, C. (2017). Effects of holistic approach using local cultural content on English oral communication ability of sixth grade students in Phrae province. OJED, 12(2), 273-291. https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/OJED/article/view/142941/105797

Taylor, S. V., & Sobel, D. M. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogy: Teaching like our students’ lives matter. Emerald.

Thumvichit, A. (2018). Cultural presentation in Thai secondary school ELT coursebooks: An analysis from intercultural perspectives.Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(11), 99-112. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i11.3533

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143-179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

Tomlinson, B. (2015). Key issues in EFL coursebooks. ELIA: Estudios De Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 15, 171-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/elia.2015.i15.09

Tomlinson, B. (2016). The importance of materials development for language learning. In M. Azarnoosh, M. Zeraatpishe, A. Faravani, & H. R. Kargozari (Eds.), Issues in materials development (pp. 1-10). Sense.

Ulla, M. B. (2019). Western-published ELT textbooks: Teacher perceptions and use in Thai classrooms. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 16(3), 970-977. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.3.13.970

Viengsang, R., & Gajaseni, C. (2016). Types and topics of culture in one series of selected English textbooks used at Thai secondary schools. The Journal of Applied Language Studies and Communication, 2(1), 47-63.

Yazan, B. (2019). Identities and ideologies in a language teacher candidate’s autoethnography: Making meaning of storied experience.TESOL Journal, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.500

Yazan, B., Canagarajah, S., & Jain, R. (2021). Autoethnography as research in ELT: Methodological challenges and affordances in the exploration of transnational identities, pedagogies, and practices. In B. Yazan, S. Canagarajah, & R. Jain (Eds.), Autoethnographies in ELT: Transnational identities, pedagogies, and practices (pp. 1-20). Routledge.