Introduction

Since the outbreak of coronavirus in early 2020, many areas in every walk of life such as education, trade, and health were disrupted. Businesses got sluggish; some even had to shut down their operations and lay off their workers; travel and tourism plummeted, and education had to undergo a major shift toward online learning. Suddenly students were forced to stay at home and rely on the internet to keep up with the lessons delivered online by their teachers. Soon problems emerged. Many students have complained of difficulties in understanding lectures explained fully through online sessions; teachers have practically no control over how the students did their assignments and quizzes without cheating; miscommunication abounded when it came to group work and detailed assignments, and the lecturers, too, felt that the absence of face-to-face sessions hindered the effectiveness of their explanation.

Learners studying foreign languages had to face even more daunting challenges as they could no longer practice productive skills in a conventional classroom setting. Learning languages through full online sessions deprived them of efficient, direct observations which are only possible during face-to-face interaction with the teacher and their peers. How language students coped with these obstacles is now being described through research. This current study was done with intention of revealing learning strategies that students used across a wide range of circumstances. More specifically, it was carried out to present a profile of strategies that students employed in their online language classes during a difficult circumstance caused by the pandemic. A learning strategy itself is defined by Little (2017) as any action that language learners perform in order to enhance their abilities in using the target language. Much research has been done about learning strategies, but research into learning strategies during the pandemic time where learners are reduced to studying full online is still not substantial. Therefore, a description of how foreign language learners coped with their online learning during the pandemic needs to be examined thoroughly. This paper sets out to present a descriptive study of strategies that some learners used to facilitate their language learning during the pandemic. The findings can help language teachers guide their learners with specific strategies that they can use in unfavorable learning conditions.

Literature Review

The previous studies reviewed in this section mostly focused on a variety of opinions from learners and teachers in their online learning during the pandemic. First, since online learning requires sound knowledge and skill in using information and communication technology (ICT), it is necessary to review the current developments in the field of education. In their study of Malaysian teachers Ryn and SC (2020) found that a lack of knowledge and confidence hampered the teachers’ effective use of ICT for teaching purposes. They strongly recommended training teachers on how to enhance their skills in using ICT so that they could deliver effective classes during the pandemic. Famularish (2020) conducted a study from the perspective of students and found that most of her respondents were keen on using ICT to enhance their learning, with WhatsApp being the most favorite means of learning. Apriani et al. (2022) also asserted the fact that college students perceived ICT as an indispensable element in their learning because they felt that it promoted enhancement in skill, knowledge, and motivation. In terms of factors that support full online learning, Lapitan et al. (2021) revealed that the stability of internet connection and teachers’ familiarity with digitalized teaching tools were pivotal in online classes. Also, interaction with the students and students’ engagement were no less important.

Transitioning from face-to-face learning to full online learning posed its own challenges. Lemay et al. (2021) noted that the transition to online learning posed not only technological and instructional challenges but also social and affective issues due to isolation and social distancing. A similar picture was captured by Maqableh and Alia (2021) who studied the responses from 1336 undergraduate students in their two surveys. More than two thirds of them reported that they had to struggle with technological and mental health problems, time management, and balance between life and education. A focus group discussion following the survey revealed further that the respondents were concerned about distraction, reduced focus, psychological problems, and management issues. An investigation of 1131 students by PH et al (2020) revealed that learning assignments, boredom, boring online processes, an inability to meet loved ones or to do hobbies, poor internet connection, and an inability to conduct laboratory courses were the factors behind the respondents’ stress. As far as the psychological aspect is concerned, Saha et al (2021) investigated the mental health of 180 undergraduate students who were studying during the pandemic and found that more than 70% of them suffered from mild to severe psychological distress during the period. Similarly, Mali and Lim (2021) found that their respondents noted that online learning was limited in terms of student-teacher interactions, group work, peer engagement, class involvement, and the ease of asking questions about technical issues. Kapasia et al. (2020) indicated that students who were using their smartphones to participate in online learning experienced anxiety, slow internet connectivity, and an unfavorable study environment. Tang (2019) also studied the difference between students who engaged in face-to-face interactions with their classmates and those who used computer-mediated communication and found that the former were better in their grammatical accuracy of some patterns. Taken as a whole, the studies reviewed above present an overall picture of learners’ cognitive and affective states that have been affected by the pandemic. This general picture serves as a basis for this research that aimed to identify the strategies English language learners used during this unfavorable learning condition.

Studying from home for a prolonged period of time deprived students of normal interaction they used to enjoy before the pandemic. The situation gave rise to boredom and stress. Irawan et al. (2020) identified from their research some affective factors that arose immediately among the students after the lockdown was imposed: boredom, mood changes due to excessive number of assignments, and their parents’ worries about being unable to afford increasing costs for smartphone credits. Camacho-Zuniga et al. (2021) also reported similar findings among students in Mexico , indicating that pandemic-induced boredom was a global concern. Ginting and Khadijah (2022) further stated that students’ boredom was caused by the inability to play with their friends. The two writers suggested that teachers use various learning techniques, use interesting media, and create online quizzes to help the students relieve their boredom. Another study by Pawlak et al. (2021) also addressed the ways of dealing with boredom by students. Their respondents reported that they played games or even left the ongoing classes in an effort to battle the stress and boredom.

In the area of language learning strategies during the pandemic, a few studies have been done although clearly there is a need for more. Lestiyanawati (2020) recently conducted a study on how teachers conducted their online classes during the pandemic and found out three main strategies, namely applying only online chat, using video conferencing, and combining both online chat and video conference. In the meantime, learners seem to be inclined toward all types of strategies, but metacognitive strategies, as indicated by Daguay-James & Bulusan (2020), are less frequently demonstrated. In contrast, an earlier study by Hashim et al. (2018) indicated that the use of three main types of strategies, namely cognitive, metacognitive, and socio affective, was still relatively prominent among their respondents. It was not clear whether this pattern of strategies remained the same or even got worse during the pandemic.

In summary, the foregoing discussion points out the need for teachers and students to be adept at utilizing ICT to maximize learning in the digital era, and underscores the psychological impact of online learning on the students. It also reveals a few factors that cause students’ mental pressure during prolonged online learning as well as how students coped with the pressure. It ends with some strategies that some teachers and learners used during the pandemic.

The current study aimed to explore the same area with the hope of digging out more information about how some English language learners made efforts to learn the language amidst the unfavorable learning conditions. The findings can enrich the literature about language learning strategies that also include those that learners use when facing difficult circumstances. Thus, the research was conducted to answer the following question:

Which were the strategies used by EFL pre-intermediate learners at the university level to cope with difficult circumstances in their online learning during the pandemic?

The research question above is divided into more specific questions as follows:

Which strategies did learners use:

- to understand lecturers’ explanations?

- to participate in online discussion during classes?

- to benefit the most from online classes?

- to overcoming boredom while studying from home?

Method

Research Design

Data for this research were gathered using questionnaires. Creswell (2009) stated that survey research studies a sample of population to present a quantitative description of attitudes or opinions of that population. It uses questionnaires or structured interviews to generalize the finding from the sample to the population.

Furthermore, Leavy (2017) argued that survey research falls under a quantitative research design and is characterized by using questionnaires as a data gathering instrument. This research was aimed at gathering specific information about learning strategies from a group of EFL learners who were taken randomly from a larger population and later generalizing the findings to the population.

Participants

The study acquired data from 257 students with various majors at Universitas Ma Chung who were taking their compulsory English course in the Even Semester of 2020 and the Odd Semester of 2020. They were estimated to be at the pre-intermediate level of English proficiency based on their scores on the university entrance test, which was equivalent to A2 level on CEFR scale. They were taken randomly out of the entire population of 1362 students with a margin of error 4.32%. The English course they were taking was directed mainly at strengthening their proficiency in the language. Before the data collection, the students were informed about the purpose of the research and asked whether they were willing to participate. All the students gave their consent. The course used a textbook which was integrative in nature, combining the lessons of discrete language elements (sentence patterns and vocabulary) and communicative exercises, which were then used for receptive and productive language skills.

Data Analysis and Results

The data analysis was done following the principle of analysis framework suggested by Cohen et al. (2018). In this framework, the key concepts should be defined first before the data collection and analysis are discussed. Thus, strategies are defined as thought, behaviors, or beliefs that learners use to help them acquire language skills efficiently and effectively (Oxford, 2017). Difficult circumstances refer to conditions that put a strain on the learners’ mental and cognitive state in such a way that hinders their smooth efforts in mastering English language.

With regard to the data collection, the data were gathered by questionnaires on Google Forms. The researcher developed the questionnaire with the help of a colleague and initially came up with a 12-item questionnaire. After it was piloted with a dozen of the researcher’s students, some items were found to be redundant and even confusing and were thus deleted. The revised questionnaire was then tried out again twice and the answers were compared. Cohen-Kappa’s coefficient of 0.71 was obtained in this test-retest reliability measure and it was decided to use this final version of the questionnaire. The questionnaires asked the respondents four closed-ended questions: (1) what methods they used to understand the lecturer’s explanation during online learning, (2) how they participated during the discussion in online sessions, (3) what they did in order to benefit as much as possible from online learning, (4) how they coped with boredom during the quarantine period, Following a taxonomy of learning strategies by Oxford (2013)who proposed three dimensions of learning strategies, questions 1, 2, and 3 were designed to capture the cognitive strategies (those dealing with processing of information), and question 4 was designed to identify the affective strategies (those related to feeling, emotion and motivation).

The section below answers the research objective, namely, reporting learning strategies that EFL learners used during their online courses during the pandemic. An analysis of descriptive statistics which counted the frequencies of responses was carried oute in order to generate the findings. The findings are presented in Tables, with the strategies ordered from the highest frequency to the lowest frequency.

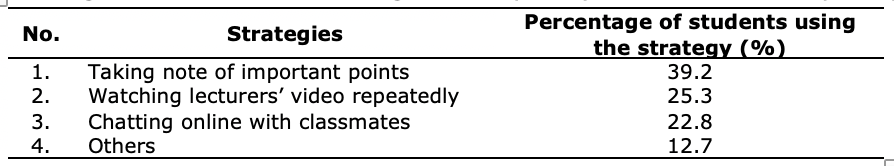

Table 1: Strategies for understanding lecturers’ explanation

As the Table above shows, most of the respondents took note of important points of the lecture. Some of them took the time to watch the video several times, and utilized the technology to discuss the lessons with their classmates.

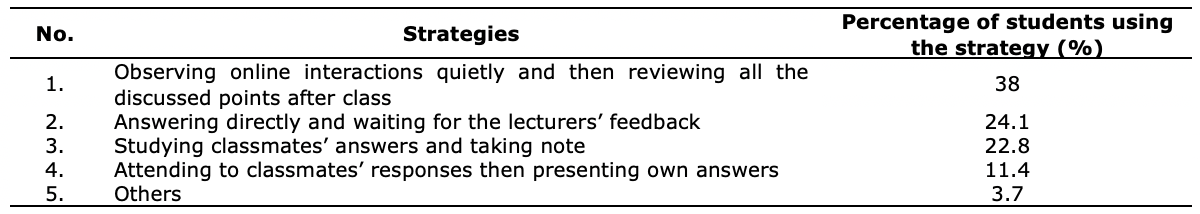

Table 2: Strategies for participating in online discussion during class

Table 2 show how respondents chose to listen to the lesson quietly and reviewed the lesson points after class. Some of them responded actively to the lecture, either by answering directly or listening to their classmates’ answers before giving their own answers.

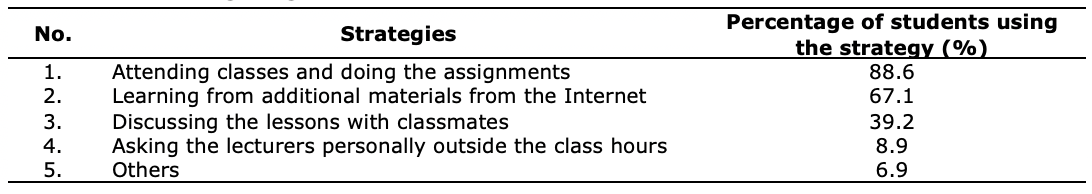

Table 3: Strategies for benefitting the most from online classes

As can be seen in the Table above, to benefit the most from online classes, most of them attended tclass and did the assignments. Quite a number of them took time to learn from additional materials from the internet, and only a small number consulted with their lecturers to refine their understanding of the lesson.

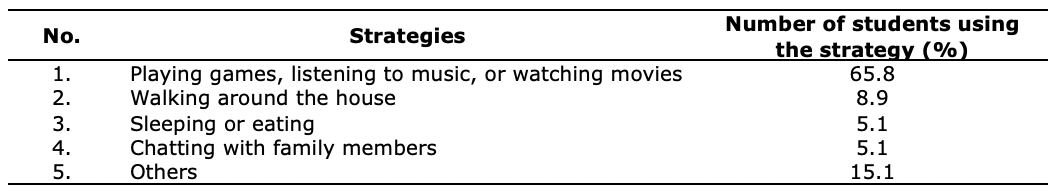

Table 4: Strategies for overcoming boredom during studying from home

As Table 4 shows, the respondents relieved boredom and stress by playing games, listening to music or watching movies. A few simply slept or ate, and a few others turned to their family members to alleviate the mental burden.

Discussion

Taking notes as a strategy for understanding lecturers’ explanation

This section discusses the finding that answers the first research question, namely, what strategies the students used to understand lecturers’ explanation. As the findings in Table 1 show, the strategy most frequently employed was note-taking. This strategy has been supported by a number of studies that assert the value of note-taking. Waite et al. (2018) state on the basis of their research that the quality of note-taking was positively correlated with lower and higher-order learning types. They also stressed the negative effect of multitasking on the quality of the notes, something that Millennial learners and their teachers need to heed. One recent study by Bahrami and Nosratzdeh (2017) asserted the value of note-taking as a learning strategy. Flanigan and Titsworth (2020) recommended on the basis of their research that students be taught to produce notes which have complete idea units as this kind of note is correlated highly with their learning gains.

Watching lecturers’ videos repeatedly as a strategy for understanding lecturers’ explanation

The second most frequently used strategy was listening to lecturers’ recorded explanations several times. Most lecturers recorded their explanations on various topics and then uploaded the recorded lectures on YouTube. The MS Teamslearning platform, which the writer uses at the university, also allows recording of the lectures so that the students can always watch the lecture several times after it is over. Obviously, this kind of technique allowed the students to watch the videos, take notes from them, and replay them in order to understand some parts better.

This current study did not conduct a follow-up interview asking the respondents why they listened to lecturers’ recorded explanation, but quite possibly the reason was not far different from what Gorissen et al. (2012) found in their research. They found that the respondents listened to the recorded lectures to compensate for their absence in the face-to-face sessions, and to prepare for the class assignments.

Another study with a relevant result was done by Vaccani et al (2014) who found that students who learned with a webcast performed better than those attending live lectures. It was the ability to view the recorded lectures several times that proved beneficial for their learning. In another study, Panther et al. (2011) stated that while face-to-face interactions were still highly favorable among the students, recorded lectures had been used for clarification and revision thanks to the possibility to pause and rewind . During times of forced isolation, there could be an increasing demand for these recorded lectures since the students and teachers could no longer enjoy face-to-face interactions. Therefore, language teachers should develop their skill of creating good videos which clearly explain important concepts or provide good models of language use for the students.

Strategies for ways of participating in the online discussion

This section discusses the findings for the second research question, namely what strategies they used for participating in the online discussion. As Table 2 above shows, most respondents employed the strategy of quietly observing the lessons and other classmates’ interactions with the lecturers and then reviewing all the important points. This predominantly quiet way of learning accords with what Ho (2020) refers to as a habit in a collective-oriented culture, which is typical of Asian students. In such culture, students feel more comfortable and secure by refraining from openly articulating their thoughts in a large class. They would rather take note of the important points of the lecture and then engage more actively in small group discussions, hence the frequent use of chatting with their classmates.

An explanation that is pertinent to this strategy is offered by Soh (2016) who contended that in Asian culture silence is perceived as a normal behavior which signals that the person is thinking, showing respect, or simply taking some time to respond while listening to others’ reactions. Thus, students keep quiet because they want to show respect to the teachers, fear that their mistakes may be seen as foolish by others, or simply want to maintain group harmony.

The frequent occurrences of reviewing and studying strategies call for a reliable learning management system that should be managed in such a way that learners can comfortably review all the important points of discussion that arose during the online session. With the possibility of a prolonged period of isolation, teachers may have to arm themselves with the skills of directing online sessions, promoting online discussions, and curating all the useful notes that their students could use to review.

In contrast to the above discussion, a considerable number of respondents preferred another more direct and spontaneous strategy, that is, responding quickly to the lecturers’ questions and waiting for the feedback. This could be taken as a gradual shift in online class participation from a reticent attitude to more spontaneous behavior, or it could be that some of the respondents possessed an impulsive style in learning a language. Still, another plausible explanation was that the responsive students may have felt more secure to answer when they were not in a physical classroom where their performance was more openly exposed to all of their classmates and the teacher. A recent study by Loh and Teo (2017) indicated that some Asian students, due to their social economic and educational background, deviated from the typically quiet stereotype of Asian culture and did not hesitate to participate openly and quickly in the class. These students no longer perceived the act of asking questions as challenging the teacher’s authority. Such a sign may usher in a gradual change of culture among educated, millennial generations in many Asian countries.

Strategies for attending classes and doing assignments

This section discusses the answer to the third research question, namely what strategies they used for benefitting the most from online classes. As Table 3 above shows, the most frequent strategy for benefitting from the online classes was attending the sessions and doing the assignments. This is a general strategy that could actually reveal a lot more if an introspective technique had been used in the data collection phase. Anyway, it indicates the degree of cognitive efforts that the respondents expended during their online learning. As Tetteh (2018) found in a study, learning strategies and class attendance are closely related. Class attendance supposedly has a significant positive impact on the learning outcome.

The usefulness of english lessons on the internet

Another frequent act that falls under this kind of strategy was learning from additional materials from the Internet. As Table 3 shows, there were a considerable number of respondents who utilized websites related to English learning during their online studies. They apparently used this strategy to cope with learning difficulties that they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study which turned out a more or less similar finding was done by Oh (2019). The study found that many EFL learners employed digital writing resources when doing their writing tasks. Apparently, realizing the usefulness of these versatile virtual-assistants, they consciously used them to enhance their English learning. Their awareness of this should be appreciated by today’s language teachers, who in turn will have to be much more knowledgeable and adept at utilizing this web-based learning aids. This is where the concept of TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge), the extent to which teachers are adept at using digital technologies becomes be relevant (Schmid et al., 2021). Digital technology has permeated educational practices and teachers have to be skillful in utilizing this technology to enhance their teaching, especially in a time where the only way of teaching students is through online classes. As discussed in the previous section, the necessity of teachers’ abilities in utilizing internet-supported learning tools cannot be underestimated (Lapitan et al., 2021). Indeed, as Cong-Lem ( 2018) suggested, today’s internet is rich with a wide range of language learning tools. There are general websites supplying linguistic inputs, blogging platforms, communication platforms, project-based learning tools, and learning management systems. Added to these are numerous web articles and videos, and chat tools that provide peer interactions and collaborative learning. During the pandemic when the lecturers’ and peers’ physical presence is minimal and lots of hours are spent at home, t students might have realized that the internet was the only available tool that could help them with their language learning.

Chatting with classmates

The respondents also showed a strong inclination toward chatting with their classmates in their efforts to learn English. As Ahmed (2019) noted from his study, students obviously utilized the chat facility in their digital devices to enhance their English language skills and to strengthen their motivation. Ahmed’s study, which was of a quasi-experimental design, revealed how his twenty subjects chatted to improve their reading and writing skills. With a particular focus on the use of WhatsApp as a means of online communication, Ying et al (2021) conducted a thorough literature review and found that among learners of different nationalities, WhatsApp is a very popular means of communication that permits the students to chat more effectively, fosters the right context for increasing conversational skills, and serves to spread lecture notifications and deadlines for tasks effectively. In this current study, although no attempt was made to see the content of the respondents’ chat, it was reasonable to conjecture that the nature of chatting with classmates seemed to give them a morale boost to keep on learning despite the pandemic situation.

The fact that many respondents in this study perceived chatting with classmates as a useful strategy suggests that during the pandemic, the need for offline human interaction grew even stronger. This is in line with the concept of communitas as discussed by Christopher et al (2020). In creating communitas through online chat, learners engaged in the “sharing of experiences without the need of formal structures for togetherness, caring and joy” (Christopher et al., 2020, p.3). In turn, this sense of sharing togetherness might have bolstered their motivation to continue learning despite the limited physical interaction. Another study by Kwakye et al (2020) reported the need of students to have a coping mechanism when they were under psychological pressure. Their in-depth study revealed that students found such a mechanism in chatting with their classmates.

Sins et al. (2011) also concluded that during online chat sessions students tended to suppress their reasoning more than when they engaged in face-to-face chat. In other words, they reasoned less when chatting online. An important point that could be inferred from this is that chatting proves to be helpful during learning. The pandemic deprived the respondents in this current study of this helpful feature of face-to-face chat; yet despite the obstacle they still employed this strategy to refine their language learning. It should also be noted that the study by Sins et al. above was conducted in 2011 when chatting applications were not as versatile and complete as they are today. Thus, today’s learners might still be able to benefit from the high-quality chatting software or apps which are capable of simulating a real-life chat. Video classes in WhatsApp and live meetings facilitated by software like Zoom, Google Meet, or MS Teams have been able to create a chatting environment that more or less resembles face-to-face interactions. When it comes to facilitating students’ chats about their lessons, it might have resolved the lack of reasoning when chatting identified by Sins et al. in their study reported above.

Another advantage that the students may have gained from their chatting with classmates is the opportunity to exchange feedback. As Liu et al (2020) noted, face-to-face feedback and e-feedback, that is feedback given through digital interaction, had a positive impact on their subjects’ academic performances.

Strategies for overcoming boredom

This section discusses the answer to the fourth research question, namely what strategies students used to overcome boredom. As discussed in the previous section, boredom which often leads to stress, is a major impediment to the quality of learning. Learners have to find ways to cope with their level of stress, and these can include the affective strategies. This is in agreement with a study by Obergriesser and Stoeger (2020) who argued that use of effective learning strategies was determined by enjoyment and boredom. They found out that enjoyment positively predicted the effective use of learning strategies. As Table 4 shows, the respondents in the present study seemed to have their own ways of overcoming boredom during the pandemic. For many of the respondents in this study, enjoyment came from playing online games. This finding was similar to that of Pawlak et al. (2014) that was discussed in the previous section. Indeed, as Amin et al (2020) found in their study, there was an important increase in online game players from the outset of the pandemic, a phenomenon that was attributable to work-life balance. Zhu (2020) explored this issue further and maintained that online games helped people to battle loneliness by interacting with other players. It follows from this that it was good for the respondents to play games and watch other entertainment in their gadgets while studying at home.

As far as the writer’s experience is concerned, simple games can work relatively well to spice up the lesson. For example, one of the games has the students find some English words from their complete names, or from their classmates’ complete names. They race to find as many words as possible, and this is enough to liven up the learning atmosphere.

Conclusion

This paper reports a survey of learning strategies by university students who were learning EFL through online classes during the pandemic. The findings showed that taking notes, watching the recorded lectures several times, quietly attending to the lectures, doing assignments, chatting with their classmates, learning independently from internet-based sources, and regulating the degree of participation during the online sessions were the most frequently employed strategies. In the affective aspect, the respondents who had to battle stress and boredom preferred playing games and watching movies.

In the light of the findings discussed above, several points could be suggested for English language teachers who have to manage their online classes during similar situations. First of all, teachers should improve their skills in recording their presentations or lectures in videos which then can be uploaded to YouTube. Some teachers know, sometimes intuitively, how to teach with a style and length that their students find most effective. The writer’s personal experience and his students’ feedback indicate that simple Power Point slides accompanied by clear and lively explanation that do not exceed 20 minutes are useful. Second, teachers have to be aware of websites and apps that their students could use to enhance their independent learning. Informing their students about these digital aids can promote independent learning. Third, since prolonged online learning is likely to affect the students’ mental health, teachers should try to make the learning atmosphere more relaxed and fun by getting the students to play simple games. Fourth, as most teachers had to hurriedly move to full online learning as soon as the pandemic broke out, very few knew how to transfer their teaching experiences to online classes. Therefore, they should be aware of their students’ feedback on how effective their online classes have been for their students. In the writer’s university, a considerable number of students complained about a surge of assignments once the teaching was moved online. The lack of lecturers’ feedback for the students’ works seemed to exacerbate the predicament. Many teachers, apparently due to ignorance or reluctance to do extra effort to deliver their teaching online, simply threw many assignments to their students and then let them go unchecked. If these issues are not handled properly, chances are the online learning will be fraught with problems that would render it ineffective.

It is necessary to point out certain limitations to the study. First, the questionnaire only consisted of five items, which would have limited the scope of the strategies of interest. The small number was actually intended to avoid respondents’ boredom caused by having to respond to many items in a questionnaire. Second, the respondents were not divided into further categories such as sex and proficiency level, which could have generated more specific profile of strategies. It is recommended, therefore, that future studies in the same area involve a larger number of respondents, with more items in the questionnaires, and with further classifications of the respondents into some variables that could reveal more specific strategies. In addition, several points in the questionnaire could be explored more deeply by conducting an in-depth interview with several respondents so as to disclose psychological and cognitive aspects of learning that mere questionnaires could not reveal.

References

Ahmed, S. T. S. (2019). Chat and learn: effectiveness of using Whatsapp as a pedagogocal tool to enhance EFL learning reading and writing skills. International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 8(2), 61-68. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.23.2019.82.61.68

Amin, K. P., Griffiths, M. D., & Dsouza, D. D. (2020). Online gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: strategies for work-life balance. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 296-302. https://doi.org/10.32584/jikj.v3i2.590

Apriani, E., Arsyad, S., Syafryadin, S., Supardan, D., Gusmuliana, P., & Santiana, S. (2022). ICT platforms for Indonesian EFL students viewed from gender during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies in English Language and Education, 9(1), 187-202. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v9i1.21089

Bahrami, F., & Nosratzdeh, H. (2017). The effectiveness of note-taking on reading comprehension of Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 6(7), 42-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.7p.308

Camacho-Zuñiga, C., Pego, L., Escamilla, J., & Hosseini, S. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ feelings at high school, undergraduate, and postgraduate levels. Heliyon, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06465

Christopher, R., de Tantillo, L., & Watson, J. (2020). Academic caring pedagogy, presence, and communitas in nursing education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Outlook, 68(6), 822-829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.08.006

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge

Cong-Lem, N. (2018). Web-based language learning (WBLL) for enhancing L2 speaking performance: A review. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 9(4), 143-152. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.9n.4p.143

Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

Daguay-James, H., & Bulusan, F. (2020). Metacognitive strategies on reading English texts of ESL freshmen: A sequential explanatory mixed design. TESOL International Journal, 15(1), 20-33. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1257215.pdf

Flanigan, A. E., & Titsworth, J. (2020). The impact of digital distraction on lecture note-taking and student learning. Instructional Science, 48, 495-524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-020-09517-2

Ginting, R. A. B., & Khadijah, R. (2022). Bornage of children's learning during pandemic and teacher's effort in overcoming it. International Seminar on Islamic Studies, 3(1), 265 – 270. https://jurnal.umsu.ac.id/index.php/insis/article/view/9569/pdf_286

Gorissen, P., van Bruggen, J., & Jochems, W. (2012). Students and recorded lectures: Survey on current use and demands for higher education. Research in Learning Technology, 20. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.17299

Hashim, H. U., Yunus, M. M., & Hashim, H. (2018). Language learning strategies used by adult learners of Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL). TESOL International Journal, 13(4), 39-48.

Ho, S. (2020). Culture and learning: Confucian heritage learners, social-oriented achievement, and innovative pedagogies. In C. S. Sanger, & N. W. Gleason (Eds.), Diversity and inclusion in global higher education: Lessons from across Asia (pp. 117-158). Palgrave Macmillan.

Irawan, A. W., Dwisona, D., & Lestari, M. (2020). Psychological impacts of students on online learning during the pandemic COVID-19.Konseli, 7(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.24042/kons.v7i1.6389

Kapasia, N., Paul, P., Roy, A., Saha, J., Zaveri, A., Malick, R., Barman, B., Das, P., & Chouhan, P. (2020). Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Children and Youth Services Review, 116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194

Kwakye, I. N., Antwi, J., Essel, C. & Yeboah, P. A.(2020). Nursing students' first clinical experience with a dying patient or the dead: A phenomenological study. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 33(10), 25-39. https://doi.org/10.9734/jesbs/2020/v33i1030262

Lapitan, L. D., Jr., Tiangco, C. E., Sumalinog, D. A. G., Sabarillo, N. S., & Diaz, J. M. (2021). An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers, 35, 116-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2021.01.012

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based and community-based participatory research approaches. Guilford.

Lemay, D. J., Bazelais, P., & Doleck, T. (2021). Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 24-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100130

Lestiyanawati, R. (2020). The strategies and problems faced by Indonesian teachers in conducting e-learning during COVID-19 outbreak. CLLIENT (Culture, Literature, Linguistics, English Teaching), 2(1), 71-82. https://doi.org/10.32699/cllient.v2i1.1271

Little, D. (2017). Strategies of language learning. In M. Byram, & A. Hu, Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 45-65). Routledge.

Liu, F., Du, J., Zhou, D. Q., & Huang, B. (2020). Exploiting the potential of peer feedback: The combined use of face-to-face feedback and e-feedback in doctoral writing groups. Assessing Writing, 47, 45-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100482

Loh, C. Y. R., & Teo, T. C. (2017). Understanding Asian students learning styles, cultural influence and learning strategies. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 7(1), 194-210. https://www.jespnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_1_March_2017/23.pdf

Mali, D., & Lim, H. (2021). How do students perceive face-to-face/blended learning as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic? The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 137-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100552

Maqableh, M., & Alia, M. (2021). Evaluation of online learning of undergraduate students under lockdown amidst COVID-19 pandemic: The online learning experience and students' satisfaction. Children and Youth Services Review, 128, 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106160

Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2020). Students' emotions of enjoyment and boredom and their use of cognitive learning strategies - How do they affect one another? Learning and Instruction, 66, 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101285

Oh, S. (2019). Second language learners' use of writing resources in writing assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(1), 60-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2019.1674854

Oxford, R. L. (2013). Teaching & researching: Language learning strategies. Routledge.

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context. Routledge

Panther, B. C., Mosse, J. A., & Wright, W. (2011). Recorded lectures don’t replace the ‘real thing’: what the students say. Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Science and Math Education: Teaching for diversity-challenges & strategies , University of Melbourne, 28-30 September, 2011, (pp. 127-132). University of Melbourne.https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/IISME/article/view/4819/5579

Pawlak, M., Derakshan, A., Mehdizadeh, M. & Kruk, M. (2021). Boredom in online English language classes: Mediating variables and coping strategies. Language Teaching Research, [Online first]. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211064944

PH, L., Mubin, M. F., & Basthomi, Y. (2020). "Learning task" attributable to students' stress during the pandemic Covid-19. Jurnal Ilmu Keperawatan Jiwa, 3(2), 203-208. https://journal.ppnijateng.org/index.php/jikj/article/view/590/329

Ryn, A. S, & Sandaran, S. C. (2020). Teachers’ practices and perceptions of the use of ICT in ELT classrooms in the pre-Covid 19 pandemic era and suggestions for the ’New Normal’. LSP International Journal, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.11113/lspi.v7n1.100

Saha, A., Dutta, A., & Sifat, R. I. (2021). The mental impact of digital divide due to COVID-19 pandemic induced emergency online learning at undergraduate level: Evidence from undergraduate students from Dhaka city. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 170-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.045

Schmid, M., Brianza, E., & Petko, D. (2021). Self-reported technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) of pre-service teachers in relation to digital technology use in lesson plans. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 112-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106586

Sins, P. H. M., Savelsbergh, E. R., van Joolingen, W. R., & van Hout-Wolter, B. H. A. M. (2011). Effects of face-to-face versus chat communication on performance in a collaborative inquiry modeling task. Computers & Education, 56(2), 379-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.022

Soh, D. H. L. (2016). The motif of hospitality in theological education: A critical appraisal with implications for application in theological education. Langham Global Library.

Tang, X. (2019). The effects of task modality on L2 Chinese learners’ pragmatic development: Computer-mediated written chat vs face-to-face oral chat. System, 80, 48-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.10.011

Tetteh, G. A. (2018). Effects of classroom attendance and learning strategies on the learning outcome. Journal of International Education in Business, 11(2), 195-219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIEB-01-2017-0004

Vaccani, J.-P., Javidnia, H., & Humphrey-Murto, S. (2014). The effectiveness of webcast compared to live lectures as a teaching tool in medical school. Medical Teacher, 38(1), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.970990

Waite, B. M., Lindberg, R., Ernst, B., Bowman, L. L., & Levine, L. E. (2018). Off-task multitasking, note-taking and lower-and higher-order classroom learning. Computers & Education, 120, 98-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.007

Ying, Y. H., Siang, W. E., & Mohamad, M. (2021). The challenges of learning English skills and the integration of social media and conferencing tools to help ESL learners coping with the challenges during COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Creative Education, 12(7), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2021.127115

Zhu, L. (2020). The psychology behind video games during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Human Behavior & Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 157-159. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.221