Introduction

Telecollaborative exchange (TE) has received much attention in the research of intercultural communicative competence (ICC). Literature in this area substantiates the advantages of TE in promoting learners’ intercultural competence (Batunan et al., 2023a; Hsu & Beasley, 2019; Tecedor & Vasseur, 2020); supporting English and culture learning (Bray & Iswanti, 2013; Chen & Yang, 2014a); sparking students’ curiosity about other cultures (Wach, 2013), and stimulating their intercultural appreciation and awareness (Okumura, 2020). On a similar note, studies (Ghasemi, 2019; Ghasemi et al., 2020; Yashima, et al., 2004) revealed that learners who desired to make global friendships and partake in worldwide events (international posture) were likely to demonstrate a higher ICC competence. Furthermore, TE can facilitate students’ ICC as TE promotes constructive discourse and supplies varied information that textbooks could not cover (O’Dowd, 2007).

Many studies (Akiyama, 2017; Angelova & Zhao, 2014; Barbosa & Lopes, 2021; Bray & Iswanti, 2013; Duraisingh et al., 2021; Foss & McDonald, 2009; Jauregi et., al, 2012; Lui & Gui, 2019; Morollón Martí & Fernández, 2016; O’Dowd, 2021; Peiser, 2016; Wach, 2013) have examined TE, but to date, the investigation of TE through the eyes of teachers within the non-Anglophone context remains an area for exploration (O’Dowd, 2015; Freiermuth & Huang, 2018; 2021; Pasand et al., 2021). Research has highlighted some emerging challenges to enacting TE (Chen & Yang, 2014b; Dugartsyrenova & Sardegna, 2019) and has mainly focused on how students perceive TE and how TE promotes their ICC (Hagley, 2020; Hsu & Beasley, 2019; Taskiran, 2019; Tecedor & Vasseur, 2020), overlooking how teachers implement and perceive TE. Scrutinizing “what teachers think, know, believe, and do” is crucial because it helps to make explicit and reflect on their day-to-day "professional decision-making" (Pajares, 1992, p.11). In some previous studies on ICC in non-Anglophone countries (Israelsson, 2016; Roiha & Sommier, 2021; Safa & Tofighi, 2021; Smakova & Paulsrud, 2020), although teachers acknowledge the significance of incorporating interculturality into their instruction, this belief is not always reflected in their day-to-day- teaching practices due to conflicting priority (Castro et al., 2004), impartial understanding of cultural elements (Larzén‐Östermark, 2008), and lack of appropriate approach to interculturality learning (Young & Sachdev, 2011).

Building on the reported challenges, this study aims to increase the information on how TE can be used to teach ICC by investigating teachers' day-to-day activities and underlying their perspectives on TE in developing students' ICC. We believe such an inquiry merits attention as it helps to gain insights into how teachers implement ideal TE to manifest their roles as cultural mediators and facilitators.

Literature Review

Teaching Intercultural Communicative Competence

Incorporating ICC into day-to-day teaching practice is becoming inevitable and calls for teachers to include it in their classes due to the demand for intercultural communication in the global era (Czura, 2016; Eren, 2021; McKay, 2018; Sercu, 2006). ICC is defined as the capacity to communicate in effective and appropriate ways in cross-cultural settings (Byram, 1997; Deardorff, 2004; Mirzaei & Forouzandeh, 2013). This approach to language learning aims to incorporate interculturality into English instruction marking the paradigm shift from language-driven instruction. Instead of being driven by form-focused approach or native speakerism, teaching English should nurture the competence to use “linguistics forms in given social situations in the target language setting” (Alptekin, 2002, p. 58).

To be a competent intercultural speaker, Bryam et al. (2002) describe the concept of ICC with five elements: “knowledge (saviors), attitude (savoir être), the skill of interpreting and relating (savoir comprendre), skills of discovery and interaction (savoir apprendre/faire), critical awareness (savoirs’engager)” (p.11). Knowledge (saviors) requires competent intercultural speakers to understand their culture and other cultures, including products, practices, and perspectives. Attitude (savoir être) refers to possessing these traits: curiosity, being open-minded, and not being prejudiced toward different cultures. Skills in interpreting and relating (savoir comprendre) refer to the capacity to comprehend, explain, and link materials or events from another culture to those from one's own. With discovery and interaction skills (savoir apprendre/faire), they should be able to use the learned knowledge and skills in direct communication with their interlocutors. Finally, in critical awareness, they should possess a comprehensive point of view about different cultures.

Experts have documented teachers’ endeavors in integrating ICC into their teaching practices, for example, incorporating cultures in teaching materials and students’ textbooks (Gómez Rodriquez, 2015; Sándorová, 2016; Siddiqie, 2011), promoting ICC in teaching strategies (Bryam et al., 2002; Chaouche, 2016; Jata, 2015; Kusumaningputri & Widodo, 2017) and assessing ICC in classrooms (Clouet, 2013). However, studies have also shown that teachers still lack the knowledge of ICC, such as what and how to assess students’ ICC (Gu, 2015) and they experience the disparity between the blueprint imposed by the government and daily teaching practices (Nguyen, 2014; Oranje & Smith, 2017; Safa & Tofighi, 2021; Young & Sachdev, 2011).

A study using semi-structured interviews by Israelsson (2016) investigated six English teachers from upper secondary schools in Sweden and their perception of IC (Intercultural Competence) in English instruction. The results suggested that the subjects did not have sufficient conceptual and pedagogical knowledge about IC. Young and Sachdev (2011) used diaries, focus groups, and questionnaires to examine the perspectives and practices related to the ICC of 36 teachers from the USA, the UK, and France. Findings showed an apparent discrepancy between teachers’ beliefs and daily teaching practices. The subjects identified such challenges as insufficient assessment, materials, and curriculum assistance. Safa and Tofighi (2021) studied Iranian teachers’ beliefs and practices about ICC. They reported that even though ICC was perceived as crucially important to teach, this belief was not fully reflected in their teaching practices. These studies demonstrated the divergence between what teachers believe, think, and do since what they understand is not put into day-to-day teaching practices (Israelsson, 2016; Safa & Tofighi, 2021; Young & Sachdev, 2011).

The implementation of TE

In implementing TE, teachers should pay attention to the types of tasks and scaffolding, their roles, and required procedures. Cultura, one model of TE developed in 1997 by Furstenberg et al. (2001), aimed at stimulating reciprocal understanding of cultures between French and American students mediated with web-based tools. In this model, students did “observation, analysis, and comparison” about their tandems’ cultures and exchange ideas and information to understand each other’s culture. Following the discussion, students developed a self-study about the target culture's authentic materials for in-depth analysis and understanding (Furstenberg et al., 2001). This model has been applied in other settings. For example, Chun (2014) reported the studies conducted in different countries; Philippines students (Domingo, 2014), Chinese students with American partners (Jiang et al., 2014), and Taiwanese students with partners from France (Liaw & English, 2014). Cultura TE encourages students to be knowledgeable of their cultures and enables them to be authentic through exchanging information (Liaw & English, 2014), enhances their reciprocal apprehension and “interpretive and expressive abilities on each other target language and culture” (Jiang et al., 2014), and improves their target language proficiency and synthesizing skills (Dominggo, 2014).

O’Dowd et al. (2020) synthesized noteworthy insights into TE implementation. First, teachers needed to use virtual exchange meetings’ strategies to build up students’ readiness before participating in the meetings. Second, during the online exchanges, teachers were responsible for chairing and guiding the whole session. As a facilitator, teachers should possess “facilitation skills such as active listening, asking good questions, summarizing and reframing, as well as learning how to manage power dynamics, and how to build a sense of safety in the virtual space and trust among the participants” (p. 5). Finally, after the online meeting, teachers needed to invite students to in-depth reflection on the session.

O’Dowd (2007) highlighted the roles of teachers in TE as, “organizer, intercultural partner, model, and coach, and source and resource” (p. 150). As an organizer, teachers need to be able to design telecollaborative activities and engage a suitable collaborator to finely integrate TE into the curriculum. A gainful intercultural partnership can be achieved when teachers build good rapport with their collaborators to facilitate learning negotiation. A decent model and coach are established when teachers set the role model of a competent intercultural speaker. Learning resources are put into action when teachers can make available resources meaningful to students. Teachers’ roles are at the heart of the successful design and implementation of TE.

Method

Research context and design

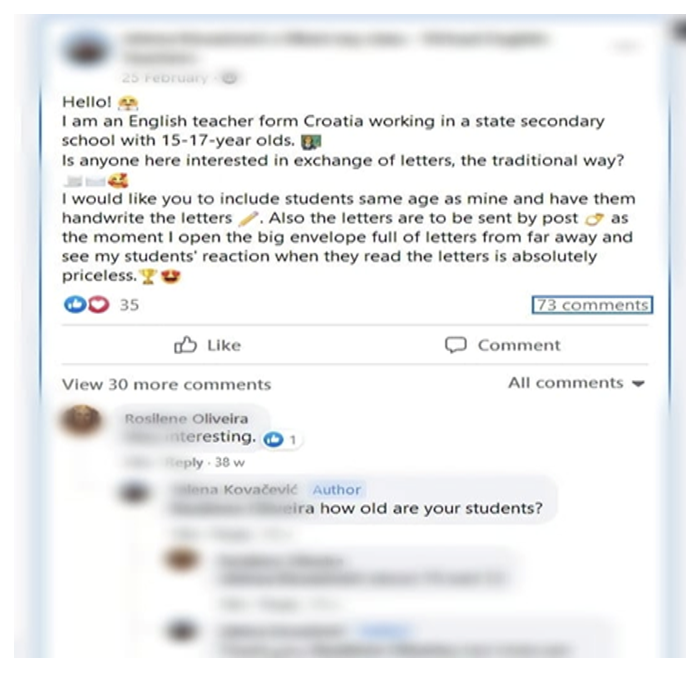

The study, conducted from October to November 2021, recruited four members of an online teacher platform on Facebook. This Facebook group had 5000 members and across Asia, Africa, Europe, South America, and North America. These teachers taught from primary to tertiary education within formal and informal settings. This group facilitated teachers to manage TE by giving a space for teachers to share their proposed models of TE. The activities included guest teacher teaching, sharing cultural elements or intercultural projects like emails/letter exchanges, joint-meeting presentations, and collaborative tasks on varied themes. These activities aimed to promote cultural exchange, help teachers to build an environment for students to enhance their English proficiency, and form a friendship with their fellow teachers across the globe. The project’s duration and collaboration were flexible depending on the preliminary agreement between teachers. Some projects may last longer in months, such as pen-palling projects, but others like cultural presentation and speaking practices are short-lived meetings in weeks.

The present case study was intended to investigate how teachers implement TE in a non-Anglophone environment and what perspective they hold about the experiences of enacting TE. Griffee (2012) states that a case study has a specific, narrow scope that aims to comprehensively analyze a topic from a real-life perspective. In this respect, this present study was intended to investigate a case situated in a particular context (Creswell & Poth, 2016) by seeing how “participants perceive the events” (McKay, 2006, p. 71).

Participant and research procedure

Twelve teachers from the online teacher group on Facebook were invited to participate in the research by sharing their experiences in the virtual exchange meetings. Of these twelve potential teachers, four teachers from different countries (Belarus, Indonesia, Croatia, and India) were willing to participate. These teachers had participated in more than forty meetings in collaboration with other teachers across the globe in different projects. The participants were chosen using a purposive sample, and accessibility was also a concern. Participation was strictly voluntary, and these four participants agreed to share their information for research purposes.

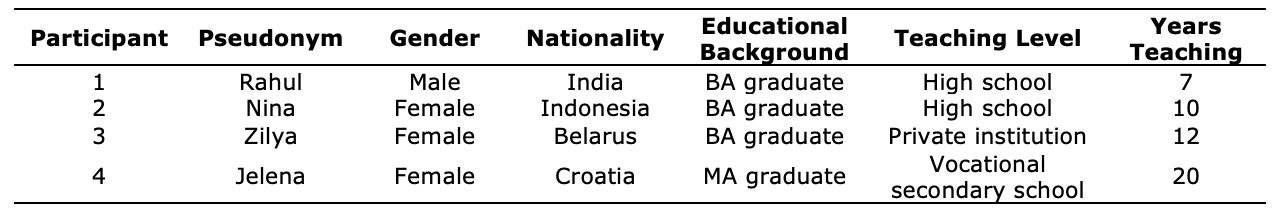

Table 1: Teachers’ participant demographic information

After explaining the research objectives and procedure to the study participants via Zoom, the first researcher made appointments to observe their online class to observe how they organized and implemented TE. The researcher only had the opportunity to observe two participants’ classes since they had resumed to face-to-face teaching. These teachers were then interviewed about their beliefs, views, and feelings about organizing TE.

Data collection and data analysis

Observational field notes and interview guideline were employed to gather the data related to the research questions, and these research instruments complemented each other in that the interview aimed to explore and clarify critical incidents relevant to the research questions. Observations were conducted and recorded to trace the implementation of intercultural exchange meetings during classroom activities. During the observation, the researcher observed the meetings and took notes about how it progressed, teacher-students interaction, and any important events. Due to privacy and safety concerns, some of the meetings could not be recorded because the students involved were very young. After attending some of the teachers' sessions, the researcher began the interviews.

The interviews took place on Zoom, and these ranged from 20 to 30 minutes. They were conducted in English and videorecorded with the participants’ consent. The unstructured interviews addressed some main concerns and other follow-up questions were developed to expand participants’ answers. The questions focused on these three main themes: participants’ demographic information, how they organized TE, and how they perceived these online meetings. Before the interview, the researcher explained the interview objective and what was in the informed consent letter. During the interview, the researcher facilitated the meeting by asking questions and clarification, raising detailed follow-up questions, listening attentively to the participants, and taking notes without interruptions.

The data from the interviews were transcribed accordingly, and the thematic analysis proposed by Braun & Clarke (2006) was implemented to code the data and identify emergent themes therefrom according to the research questions. The data was read more than once to find out the relatedness of the data and subsequently identify data patterns. To minimize the subjectivity of the researchers’ interpretation, member checking was executed by requesting the participants to validate the analysis results.

Findings

The enactment of TE

An online group on Facebook for teachers has served as a venue for teacher collaboration across geographical boundaries and time zones to share ideas on how to provide students with ample opportunities to communicate in English and make friends with people from overseas. The teachers working at a formal institution (Jelena, Nina, and Rahul) managed to arrange some meetings for TE during schooling hours, yet their counterpart (Zilya) who worked at an informal institution found it more flexible to arrange the meetings in her schedule. Regardless their institution types (formal and informal educational institutions), the study participants did not include students’ engagement in the telecollaboration as part of assessing and giving students’ grades.

The tasks applied in TE posted on this Facebook group were varied: cultural and topical PowerPoint presentation, pen palling, collaborative projects, cooking demonstrations, music and dance performances, a travel photo project, debates, competitions, speaking clubs, etc. The teacher negotiated the technical issues or how they would approach the meetings, such as the lesson focus, how the lesson was organized, how many students should take part, and which platform they should use. The teachers discussed the students’ roles in the meeting, such as who was in charge of pre-activity, main activity, and post-activity, and who was responsible for technical issues, such as creating the Zoom link, taking pictures, preparing the certificates, and doing the recording. The study participants agreed that organizing and partaking in TE

required considerable effort. To quote Jelena’s excerpt, “…it is quite a lot of work beforehand” (Jelena’s Story 6).

Figure 1: Jelena’s invitation to the group for collaboration

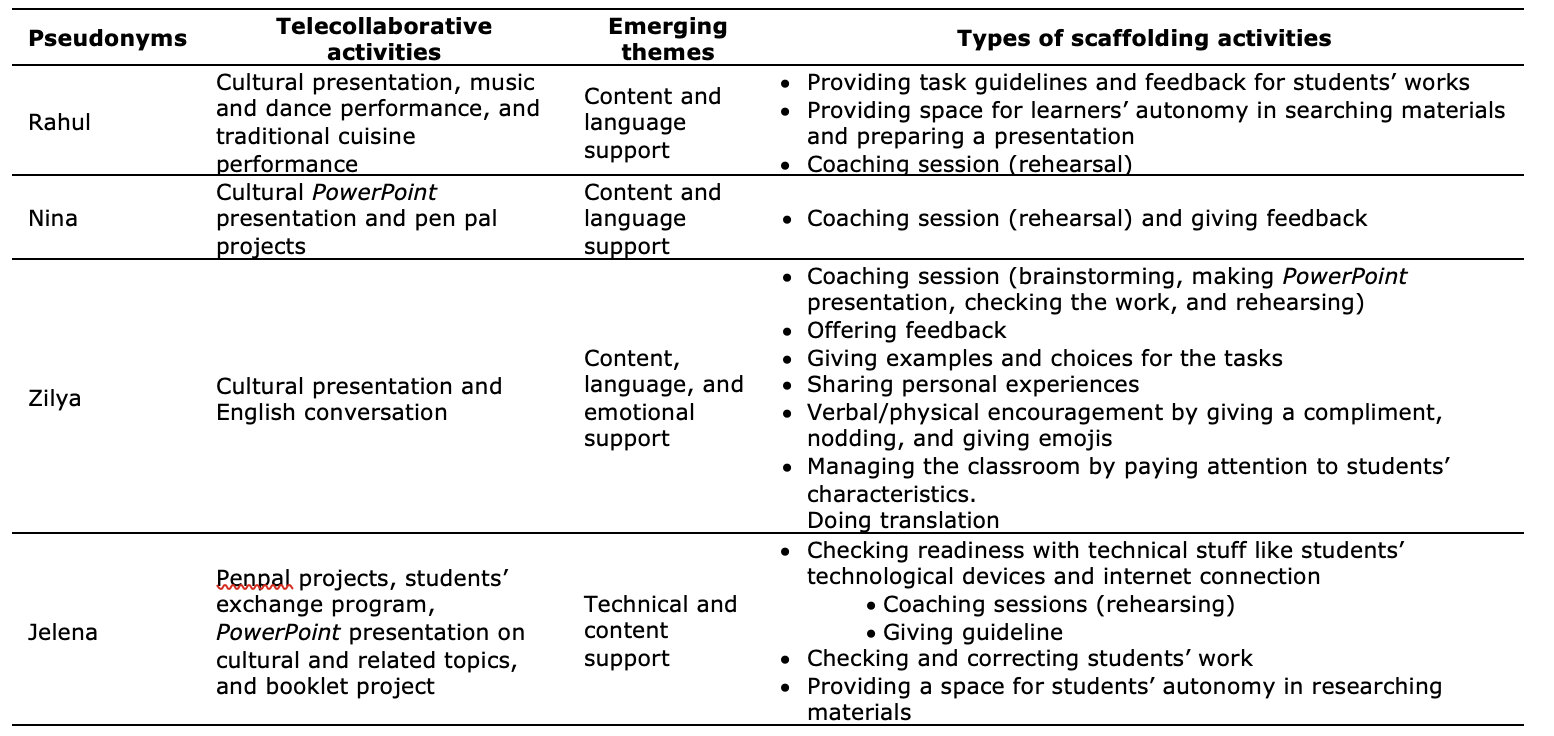

Before the meeting, teachers provided scaffolding to prepare the students for the meeting. Table 2 below summarizes the teacher scaffoldings.

Table 2: Teachers’ participant scaffolding activities

The research findings demonstrated that teachers performed a significant role in scaffolding. These four participants held coaching sessions to prepare the students to participate in the exchanges. Jelena, for instance, spent her time correcting students' work and giving them practice. Similarly, Zilya offered her support and assistance depending on students’ readiness and English proficiency. For starters and beginners, she assisted them in brainstorming ideas, making PowerPoint presentations, correcting their grammar mistakes, and rehearsing with them. She said:

Let us speak first about class. To help my students prepare for the class, I helped them to find the pictures. They came to my individual lesson. I asked them different questions, and we searched for the pictures together. Then, we analyzed what to write. I made an agenda (for their presentation), so their presentation could be about their age, blood sign, date of birth and so on. We wrote this message together. I always looked through the message to address any grammar mistakes. I assigned them homework. They needed to learn by heart. They came to my next lesson, and I checked their works. After that, we were ready to meet. When we met, I told my students the order of presentation. (Zilya’s Story 5)

In Rahul’s experience, he let the students prepare the PowerPoint on their own and he noticed that his students were fast and autonomous learners who learned from YouTube. However, he was ready with his feedback and ideas to support them. Nina allocated two to three meetings beforehand for helping students with practice and feedback to better their work. During the cultural exchange meetings, these teachers assisted their students with their social presence, extended follow-up questions, the use of L1, technical assistance, role modeling, and clarifying misunderstandings. The teacher’s use of L1 and technical assistance were performed during a meeting between Indonesian and Mongolian students. For instance, one of the students, Michelle, did not realize that her PowerPoint presentation was not on a full screen before she began, so the teacher used L1 to help her put it on a full screen. The student kept saying sorry as it took time for her to make it and the teacher assured the student by saying, “It is ok, we are studying. No worries” (Observation note, October 15th, 2021).

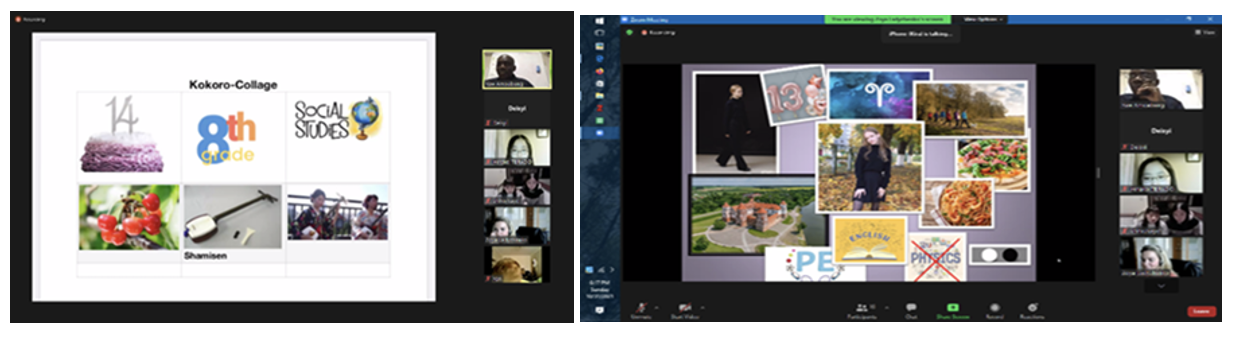

The research findings also showed that the teachers played a key role as intercultural facilitators to help students engage actively in the meetings and to reduce the gap in culture and language proficiency between students during the meetings. Teachers' beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes about ICC were reflected through the teaching practices at the meetings. In one of the meetings involving teachers and students from Belarus and Japan, Zilya from Belarus performed her role as a facilitator by listening attentively, asking follow-up questions, summarizing, and creating a safe environment for the students. She demonstrated extensive knowledge of her home and foreign cultures. The meeting was about introducing oneself using pictures in a PowerPoint presentation and students needed to explain and demonstrate how to make something, such as origami. The meeting started when Zilya greeted each student in the Zoom room and some of their names were written out in Japanese. She pointed out the differences in the writing system and her difficulty in reading the names. Then, she asked the students and teacher from Japan to read the names for her and she tried her best to copy the pronunciation. She also showed interest in how the Japanese students addressed their teachers. Yaw, an English teacher from Ghana, who was a proficient Japanese speaker and had lived in Japan for more than 20 years, explained and added further information about the use of san. Students from Japan at the time were the first starters and they seemed shy and hardly talked. Zilya provided scaffolding by asking some extended questions after the presentation to encourage the students to talk more like “Do you live in an apartment? Is the food sweet? Do you play piano? Can you play and perform it for us? “Zilya, showed her positive affirmation by nodding, smiling, and using positive and encouraging feedback and comments on the students’ presentation and answers. In addition, after each student did their presentation, these two teachers provided additional information. Yaw shared the use of Kun and Chan to address Japanese girls and boys. He elaborated on the use of yukata, a traditional woman's dress worn during summer or on a firework festival” (Observation note, October, 24th 2021).

Figure 2: PowerPoint presentations about self-introduction by the students from Belarus and Japan

The observation notes confirmed her responses in the interview. She believed that students needed to be aware of differences and be empathetic at the same time. She further said that intercultural meetings aimed at the exchange of ideas also articulated her beliefs about these exchanges.

… there were also some students who could compare and say our culture is better or worse. I have never heard from my students about that, but if they told me that, I would say you can’t say that your culture is better or worse. We should respect any cultures (Zilya’s Story 10).

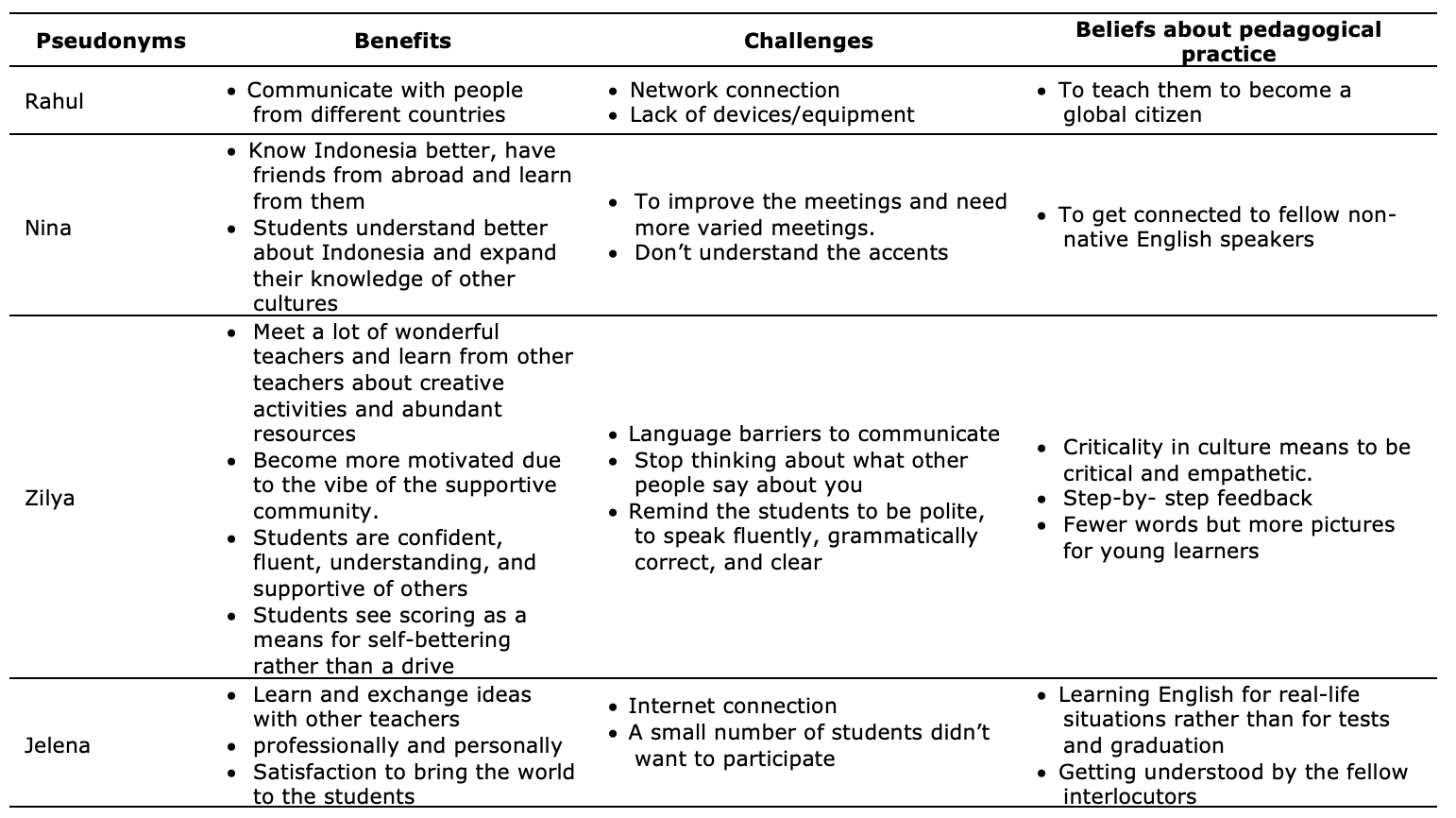

Teachers’ perception towards TE

The teachers demonstrated a positive perception towards TE, despite the challenges encountered, such as technical issues (internet connection and devices/equipment), behavioral aspects, and language barriers (understanding accents). They reported benefits from these meetings for students and teachers. The researchers also explored their held beliefs of the practices of enacting TE. The overview of teachers’ perceptions is presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3: Teachers’ perception of TE

The participants showed their interest in international communication through their interchanges with fellow teachers across the globe and expressed their desire to grow professionally and improve their day-to-day teaching practices. Jelena, an English teacher at a business school in Croatia with more than 20 years of experience and an awardee of one of the best teachers in Croatia from the Ministry of Education, was motivated to enact and take part in TE because she wanted to give her students meaningful learning opportunities for them to use English in real-life situations. Furthermore, she mentioned that her immediate professional environment did not give her much opportunity to improve herself.

For me personally, I am eager to learn. For many years after graduating, it seems like you are the only authority. I am not happy with that. I wanted to learn, I wanted to progress, and I wanted to develop further (Jelena’s Story 9).

She believed that engaging in global telecollaboration is one of her endeavors to grow professionally. In addition, she mentioned that the students benefited from expanding their cultural knowledge, making friends with people across the globe, making use of their English in a natural context, and engaging in authentic learning experiences with natives from different cultures. Some students’ stereotypes toward particular nationalities were challenged, and they finally embraced the beauty of diversity.

Just like Jelena, Zilya saw the dual benefits of what TE had offered. She mentioned the support of a teacher from the group who bravely supported the organization of the meetings.

I am grateful and thankful for Matea. She gently pushed me. She said, let us start international meetings. I did not know how to start. She really helped me a lot. You got to meet a lot of wonderful teachers (Zilya’s Story 6).

She also highlighted how teachers in the Facebook group inspired her with their great resources, teaching methods, experiences, and immense and unending support. Zilya observed how these exchange meetings benefited her students in their speaking skills, attitude, and motivation. She noticed that the students broke the barrier of communication and were no longer afraid to speak. More interestingly, they were kind-hearted and supportive of first-time students. Students would immediately attend the meetings when she informed them. She informed them that good score was no longer the focus.

Rahul and Nina performed an international posture. Rahul chronicled the story of his first participation in an international meeting after seeing a post on the British Council during the pandemic. After the meeting, he contacted other teachers who shared information about other international encounters. He admitted that it was like “a window to the global world”. Since then, he has been motivated to connect his students with people from all over the world so they can have the same experience. Rahul has participated in more than 40 meetings so far and proudly shared that his school, students, and he appeared in a newspaper story, which further motivated the students

Nina from Indonesia shared the same concern as shown in her interview excerpt. She said, “Well, actually, for the first time, it was my dream from a long time ago to have some teacher friends from abroad and exchange ideas”. It is interesting to note that Nina elicited World-Englishes postulation. She repeatedly stressed the importance of making friends with people from other countries, particularly for knowing their cultures and embracing cultural diversity. Nina mentioned her students’ comments after independently searching for cultural presentation. This experience made them aware of how wonderful Indonesia is and how proud they were of being Indonesians. They no longer underestimated their own country. These four teachers believed that these encounters not only exposed the students to global cultures, but also raised their awareness as global citizens and encouraged them to acknowledge cultural diversity.

Jelena illustrated her belief about the importance of being understood by her fellow interlocutors in her dialogue with her students. Some of her students were not confident enough to join in the meeting because of their unsatisfactory results on a grammar test.

… some students were often discouraged from taking part in this activity because they said they were not good at English because their grades on grammar test were not up to the standard. I kept convincing them that it was not about grammar here; it was not about accuracy but it was about communication. I wanted to make them realize and accept these ideas. It is important to communicate and get your messages across (Jelena’s Story 13).

This statement was in line with her motivation to organize the meeting since she wanted her students to use English in real-life situations and “converse with foreigners”. In Zilya’s point of view, criticality in culture is like the two sides of a coin, and she also shared her thoughts about how to deal with it.

We had two different sides; we could criticize or empathize. Empathy is a good feature for every human being. You should be understanding and put your shoes to support others. At the same time, some students could compare and say our culture is better or worse. I have never heard from my students about that, but if they told me that, I would say you can’t say that your culture is better or worse. We should respect any cultures (Zilya’s Story 11).

Her belief in students’ criticality is also reflected after the meeting when one of her Belarusian students commented that they prepared better than their tandem partner in the meeting. Their tandem partner seemed to think a lot and did not know how to answer.

…I just tried to say it in their first meeting. You know that some problems with Zoom sessions could happen. You need to be flexible with equipment. It takes time. You need to be patient. No comparing. There will also be some cases that when you will be worse and you don’t need to be proud. Yes, you are better than yourself yesterday. But you don’t need to compare yourself with others because there will be other students better or worse than you. You are better than yourself yesterday (Zilya’s Story 11).

Rahul shared one incident when his student expressed his curiosity regarding religion in a meeting with Slovenians. Before meeting their partner from Slovenia, this Hindu student had done an independent search, asking about why there were not many mosques in Slovenia. In Rahul’s narration, he felt the teacher from Slovenia was not comfortable with the question. He admitted that students could be critical beyond the teacher’s control and expectation. Rahul believed that teachers needed to make the students understand that differences exist: “the world is not limited to their school, village, and town. The world is too big and different in culture, everything and tradition”.

Discussion

The present study has shown how teachers perceive and enact TE framed in outer and expanding circle contexts. The findings underscored the importance of teachers’ roles and competencies as intercultural mediators/facilitators (O’Dowd, 2007; 2015) in organizing and hosting TE, providing sufficient scaffolding, and performing unflagging commitment and engagement. Teachers are expected to perform their creativity and innovation in designing interactive, appealing, and meaningful activities for the students and build international networking and a good rapport with fellow English teachers from abroad. In addition, they need to learn the skills for communicating and negotiating the designed activities or taking part effectively in other teachers’ TE projects. Teachers need to supply the students with a series of scaffoldings before, during, and after TE sessions, ranging from content-related, linguistic, technical, to emotional support for successful engagement in TE. Equally important is that they need to exemplify how to be a competent intercultural speaker. Organizing TE needs teachers’ dedication to prepare the activities and prepare the students for meaningful participation. However, the teachers hardly addressed post-TE activities as these participating teachers predominantly focused on matters before and during TE. O’ Dowd et al., (2020) suggest that TE requires complete preparation, starting from equipping the students to take part in the meetings, facilitating the meetings, and leading students in internalizing the learning experiences through in-depth reflection. These multiple tasks indicate that teachers need assistance and training on how to implement reflection after TE. Moreover, the most frequent TE task was exchanging information (O’Dowd & Ware, 2009), focusing on surface cultures. This predominance of such task is, in large part, related to the fact that these learners are primarily young and beginner English learners who need more scaffolding. By implication, they are in the initial phase of acquiring global cultures, being exposed to different accents, and building their self-confidence as well as English proficiency. However, involving young learners in intercultural exchanges is an essential initial endeavor for raising cultural awareness and understanding (Magos et al., 2013; Okumura, 2020).

The finding demonstrates the importance of teachers’ beliefs in their teaching practices (Pajares, 1992) as these beliefs govern how they deliver their instruction. These teachers engaged their students in TE because they believed that TE prepares the students to be world citizens by being connected and understood. This can be achieved by using English in real-life communication with fellow English learners and building critical thinking and empathy as the basis for establishing good rapport. Furthermore, TE benefits both teachers and students. As reported in previous studies, students gain the opportunity to expand the knowledge of their own home and their interlocutors’ cultures (Durainsingh et al., 2021; Lee & Markey, 2014; Okumura, 2020), making friendships with fellow English learners globally, experiencing learning experience firsthand from natives of particular cultures (O’Dowd, 2021), and suppressing stereotypes while promoting a positive attitude toward different cultures (Kirsh, 2008; Batunan et al., 2023a). From the teacher’s side, study participants believed that the exchange meeting was vital for their professional growth and for spicing up everyday teaching practices. This supports the simultaneous development of teachers’ professional development (Batunan et al., 2023b) and international posture. Notwithstanding, it remains questionable whether possessing an international posture encourages teachers’ engagement in these global meetings and nurtures their international postures.

Conclusion

This research has examined four teachers’ perceptions and implementation of TE in meetings held on Zoom. The research findings have attempted to respond to the lack of knowledge regarding how teachers and students, as non-native speakers of English from outer and expanding circles, organize and perceive TE in a non-Anglophone context. More specifically, the research has demonstrated the importance of diverse scaffoldings in the enactment of TE, involving content-related, linguistic, emotional, and technical support. Besides, it has highlighted the challenges to the successful use of TE and underscored the need for support and training to better assist teachers’ practice in integrating TE into their regular lessons and reflecting on post-TE activities. Teachers’ engagement in TE has given the teachers the opportunity to grow professionally and personally through their direct engagement and communication with teachers from abroad. This opportunity further refines their beliefs about how they should equip their students to function effectively in this multicultural world. The impossibility of recording all study participants’ cultural exchange meetings due to the student's privacy and safety limited this study, so longer observation is required to gain richer findings. To extend studies of this sort, future research is advised to engage in ethnographic study that enables the researchers to closely engage with the participants and their settings.

References

Akiyama, Y. (2017). Vicious vs. virtuous cycles of turn negotiation in American-Japanese telecollaboration: Is silence a virtue? Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(2), 190–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2016.1277231

Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal, 56(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.1.57

Angelova, M., & Zhao, Y. (2014). Using an online collaborative project between American and Chinese students to develop ESL teaching skills, cross-cultural awareness and language skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(1), 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.907320

Barbosa, M. W., & Ferreira-Lopes, L. (2021). Emerging trends in telecollaboration and virtual exchange: A bibliometric study. Educational Review, 75(3), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1907314

Batunan, D.A., Cahyono, B.Y., Khotimah, K. (2023a). Nice to E-meet You program to facilitate EFL lower high school students’ intercultural communicative competence: A case study from Indonesia. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal (CALL-EJ), 24(3), 46-68

Batunan, D. A., Kweldju, S., Wulyani, A. N. & Khotimah, K. (2023b). Telecollaboration to promote intercultural communicative competence: Insights from Indonesian EFL teachers. Issues in Educational Research, 33(2), 451-470. http://www.iier.org.au/iier33/batunan.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bray, E., & Iswanti, S.N. (2013). Japan-Indonesia intercultural exchange in a Facebook group. The Language teacher, 37(2), 29-34. https://jalt-publications.org/sites/default/files/pdf-article/37.2tlt_art2.pdf

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1c3

Castro, P., Sercu, L., & Méndez García, M. C. (2004). Integrating language-and-culture teaching: An investigation of Spanish teachers' perceptions of the objectives of foreign language education. Intercultural Education, 15(1), 91-104.https://doi.org/10.1080/1467598042000190013

Chaouche, M. (2016, December). Incorporating intercultural communicative competence in EFL classes. ASELS Annual Conference Proceedings, Arab World English Journal (pp. 32-42). https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2895538

Chen, J. J., & Yang, S. C (2014a): Promoting cross-cultural understanding

and language use in research-oriented Internet-mediated intercultural exchange. Computer

Assisted Language Learning, 29(2), 262-288. http://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.937441

Chen, J. J., & Yang, S. C. (2014b). Fostering foreign language learning through technology-enhanced intercultural projects. Language Learning & Technology, 18(1), 57–75. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44354

Chun, D. M. (2014). A meta-synthesis of cultura-based projects In D. M. Chun (Ed.), Cultura-inspired intercultural exchanges: Focus on Asian and Pacific languages. (pp. 33–63). National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Clouet, R. (2013). Understanding and assessing intercultural competence in an online environment: A case study of transnational education programme delivery between college students in ULPGC, Spain, and ICES, France. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 26, 139-157. http://hdl.handle.net/10553/45411

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Czura, A (2016). Major field of study and student teachers’ views on intercultural communicative competence. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2015.1113753

Deardorff, D. K. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States. [Doctoral dissertation]. North Carolina State University.

Domingo, N. P. (2014). UHM-UCLA Filipino Heritage Café and the Films quest for identity In D. M. Chun (Ed). Cultura-inspired intercultural exchanges: Focus on Asian and Pacific languages (pp. 139–155). National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Dugartsyrenova, V. A., & Sardegna, V. G. (2019). Raising intercultural awareness through voice-based telecollaboration: perceptions, uses, and recommendations. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 205-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2018.1533017

Duraisingh, L. D., Blair, S., & Aguiar, A. (2021). Learning about culture(s) via intercultural digital exchange: Opportunities, challenges, and grey areas. Intercultural Education, 32(3), 259-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1882759

Eren, Ö. (2021). Raising critical cultural awareness through telecollaboration: Insights for pre-service teacher education. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(3), 288-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1916538

Foss, P., & McDonald, K. (2009). Intra-program email exchanges. CALL-EJ Online, 10(2), 1-9.

Freiermuth, M. R., & Huang, H. (2018) Assessing willingness to communicate for academically, culturally, and linguistically different language learners: Can English become a virtual lingua franca via electronic text-based chat? In B. Zou & M. Thomas (Eds.), Handbook of research on integrating technology into contemporary language learning and teaching. IGI Global.

Freiermuth, M. R., & Huang, H. (2021). Zooming across cultures: can a telecollaborative video exchange between language learning partners further the development of intercultural competences? Foreign Language Annals, 54(1), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12504

Furstenberg, G., Levet, S., English, K., & Maillet, K. (2001). Giving a virtual voice to the silent language of culture: The cultura project. Language Learning & Technology, 5(1), 55–102. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstreams/5f8d1a33-abfa-4f20-aa19-fc62658aa5ea/download

Ghasemi, A. A. (2019). A cognitive attitudinal self-based (CAS) model of intercultural communicative competence: A study on learners of English in Iran [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Arak University.

Ghasemi, A. A., Ahmadian, M., Yazdani, H., & Amerian, M. (2020). Towards a model of intercultural communicative competence in Iranian EFL context: Testing the role of international posture, ideal L2 self, L2 self-confidence, and metacognitive strategies. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 49(1), 41-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2019.1705877

Griffee, D. T. (2012). An introduction to second language research method: Design and data. TESL-EJ Publications. http://www.tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej60/sl_research_methods.pdf

Gu, X. (2015). Assessment of intercultural communicative competence in FL education: A survey on EFL teachers’ perception and practice in China. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16(2), 254-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2015.1083575

Hagley, E. (2020). Effects of virtual exchange in the EFL classroom on students' cultural and intercultural sensitivity. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 21(3), 74-87. http://callej.org/journal/21-3/Hagley2020.pdf

Hsu, S.-Y. S., & Beasley, R. E. (2019). The effects of international email and Skype interactions on computer-mediated communication perceptions and attitudes and intercultural competence in Taiwanese students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1), 149-162. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4209

Israelsson, A. (2016). Teachers’ perception of the concept of intercultural competence in teaching English [Master’s thesis, Stockholm University]. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:940669/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Jata, E. (2015). Perception of lecturer on intercultural competence and culture teaching time (Case Study). European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 1(3), 176-180. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejis.v3i1.p197-201

Jauregi, K., de Graaff, R., van den Bergh, H., & Kriz, M. (2012). Native/non-native speaker interactions through video-web communication: a clue for enhancing motivation? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 25(1), 1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2011.582587

Jiang, S., Wang, H., & Tschudi, S. (2014). Intercultural learning on the web: Reflections on practice. In D. M. Chun (Ed.), Cultura- inspired intercultural exchanges: Focus on Asian and Pacific languages (pp. 127–143). National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Kirsh, C. (2008). Teaching foreign languages in the primary school. Continuum.

Kusumaningputri, R., & Widodo, H. P. (2018). Promoting Indonesian university students' critical intercultural awareness in tertiary EAL classrooms: The use of digital photograph-mediated intercultural tasks. System, 72, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.10.003

Larzén-Östermark, E. (2008). The intercultural dimension in EFL-teaching: A study of conceptions among Finland-Swedish comprehensive schoolteachers. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(5), 527-547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802346405

Lee, L., & Markey, A. (2014). A study of learners’ perception of online intercultural exchange through Web 2.0 technologies. ReCall. 26(3). 281-297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344014000111

Liaw, M.L., & English, K. (2014). Cultura inspired intercultural exchanges: focus on Asian and Pacific languages. In D. M. Chun (Eds.), Atale of two cultures (pp. 67–90). National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Lui, H., & Gui, M. (2019). Developing an effective Chinese-American telecollaborative learning program: an action research study.Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1633355

Magos, K., Tsilimeni, T., & Spanopoulou, K. (2013). Good morning Alex–Kalimera Maria: Digital communities and intercultural dimension in early childhood education. Intercultural Education, 24(4), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2013.812401

McKay, S. L. (2018). English as an international language: What it is and what it means for pedagogy. RELC Journal. 49(1). https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033688217738817

McKay, S.-L. (2006). Researching in second language classrooms. Lawrence Erlbaum. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781410617378

Mirzaei, A., & Forouzandeh, F. (2013) Relationship between intercultural communicative competence and L2-learning motivation of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 42(3), 300-318. http://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2013.816867

Morollón Martí, N. M., & Fernández, S. S. (2016). Telecollaboration and socio pragmatic awareness in the foreign language classroom. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2016.1138577

Nguyen, L. (2014). Integrating pedagogy into intercultural teaching in a Vietnamese setting: From policy to the classroom. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 9(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/18334105.2014.11082030

O'Dowd, R. (2007). Evaluating the outcomes of online intercultural exchange. ELT Journal, 61(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm007

O'Dowd, R. (2015). Supporting in-service language educators in learning to telecollaborate. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 63–82. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44402

O’Dowd, R. (2021). What do students learn in virtual exchange? A qualitative content analysis of learning outcomes across multiple exchanges. International Journal of Educational Research, 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101804

O’Dowd, R.., Sauro, S., & Spector-Cohen, E. (2020). The role of pedagogical mentoring in virtual exchange. TESOL Quarterly, 54(1), 146-172. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.543

O’Dowd, R., & Ware, P. (2009). Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 173-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220902778369

Okumura, S. (2020). Design and implementation of a telecollaboration project for primary school students to trigger intercultural understanding. Intercultural Education, 31(4), 377-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2020.1752546

Oranje, J., & Smith, L. F. (2018). Language teacher cognitions and intercultural language teaching: The New Zealand perspective.Language Teaching Research, 22(3), 310-329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817691319

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

Pasand, P. G., Amerian, M., Dowlatabadi, H., & Mohammadi, A. M. (2021). Developing EFL learners’ intercultural sensitivity through computer-mediated peer interaction. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 50(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2021.1943496

Peiser, G (2015). Overcoming barriers: Engaging younger students in an online intercultural exchange. Intercultural Education, 26(5), 361–376. http://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2015.1091238

Gómez Rodríguez, L. F.. (2015). The cultural content in EFL textbooks and what teachers need to do about it. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(2), 167–187. http://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272

Roiha, A., & Sommier, M. (2021). Exploring teachers’ perceptions and practices of intercultural education in an international school. Intercultural Education, 32(4), 446–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1893986

Safa, M. A., & Tofighi, S. (2021). Intercultural communicative competence beliefs and practices of Iranian pre-service and in-service EFL teachers. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2021.1889562

Sándorová, Z. (2016). The intercultural component in an EFL course-book package. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 4(3), 178-204. https://doi.org/10.1515/jolace-2016-0031

Sercu, L (2006). The foreign language and intercultural competence teacher: The acquisition of a new professional identity. Intercultural Education, 17(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980500502321

Siddiqie, S. A. (2011). Intercultural exposure through English language teaching: An analysis of an English language textbook in Bangladesh. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 15(2), 109-127. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ979918.pdf

Smakova, K., & Paulsrud, B. (2020). Intercultural communicative competence in English language teaching in Kazakhstan. Issues in Educational Research, 30(2), 691–708. https://www.iier.org.au/iier30/smakova.pdf

Taskiran, A. (2019). Telecollaboration: Fostering foreign language learning at a distance. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 22(2), 86-96. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/eurodl-2019-0012

Tecedor, M., & Vasseur, R. (2020). Videoconferencing and the development of intercultural competence: Insights from students’ self‐reflections. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 761–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12495

Wach, A. (2013). Polish teenage students’ willingness to engage in on-line intercultural interactions. Intercultural Education, 24(4), 374-381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2013.814214

Yashima, T., Zenuk-Nishide, L., & Shimizu, K. (2004). The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Language Learning, 54(1), 119-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00250.x

Young, T. J & Sachdev, I (2011). Intercultural communicative competence: Exploring English language teachers’ beliefs and practices.Language Awareness, 20(2), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2010.540328