Introduction

Assuming teachers' talk as a primary medium of providing input to learners in the language classrooms (Moser et al.,2012), and the fact that “teachers control what goes on in classrooms primarily through the ways in which they uselanguage” (Johnson, 1995, p. 9), a fundamental inquiry occupying educational researchers mind is how teachers’discourse facilitates knowledge construction. Rymes (2008) maintained that “teachers are best situated to study thelocalized and ever-changing discourse patterns specific to their own classrooms”, by investigating classroom talk (p.8). Classroom talk is operationally defined as an institutional talk distinct from the ordinary conversation in which there is an unequal power exchange system. In this system, teachers are qualified to distribute topics and turns among students and assess learners’ cooperation in interactions through repairs (Markee, 2000).

Recent research found that teachers’ talk is associated with quality and length of students’ replies (Molinari et al., 2013; Shintani, 2013; Shintani & Ellis, 2014). Previous studies offered extensively described events in the classroom and assumed that classroom talk affects learning. However, only few research studies attempted to examine it from a language learning behavior perspective (e.g., Shintani, 2013; Shintani & Ellis, 2014). As argued by Long (1996) and Lyster (1998), second language learning is directly under the influence of classroom talk. Examples of target languageare provided through instructional exchanges between teacher and students as they use target language and obtain useful feedbacks. SLA researchers agree that classroom talk might facilitate second language learning by directing and heightening learners’ attention to linguistic meanings and forms which is necessary for language learning (Markee & Kasper, 2004). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate classroom talk in some EFL classrooms using Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2013) meta-functions framework.

Theoretical framework

Following Halliday (1978), a systemic functional branch was introduced to the study of discourse and talk. He believed that language is a resource of sense making being negotiated in an authentic context. He maintained that pure linguistic analysis cannot deliver insightful visions on the nature of a particular discourse. However, what is needed is a functional analysis which can delineate why and how a particular linguistic choice is made in a particular instance of it. Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) argued that it is impossible to dissociate language from its context of use as language is realized through texts and meaning emerges as a result of interactions within those texts.

Previous studies used systemic functional linguistics (SFL) as their framework to analyze teachers’ talk in their classes. For instance, Rodrigues and Thompson (2001) investigated textual cohesion in two science classes. The degree of cohesion was estimated by a cohesive harmony index. The results showed that there should be a balance in the use of cohesion devices in teachers’ talk as both excessive and inadequate use of them may hinder comprehension. There searchers argued that lack of cohesion may make it impossible for leaners to comprehend a text while overuse of cohesive devices can make a text look pedantic. Additionally, Young and Nguven (2002) compared interactive teacher talk with textbooks as practices in teaching scientific subjects. Representations of physical and mental meaning, lexical packaging and rhetorical structure of reasoning were considered important elements of scientific meaning. The results showed that teacher talk included examples of grammar metaphors and both talk and textbooks used similar thematic organizations. The difference lay in the fact that teacher and students established thematic organizations through interactions. Jawahar and Dempster (2013) emphasized training on functional use of language for science English teachers. They studied teachers talk from three science teachers in an African context. The results revealed that with increasing practice ESL students, lexical cohesion increased while nominalization and lexical density did not change.

Wolf et al. (2005) examined Grade 1 to 8 students’ reading comprehension. Accountable talk and academic rigor were the focus of this study. It was found that teachers talked more than students. Elicitations of students’ knowledge and prompting their thinking were the dominant teacher moves. Students provided brief replies especially when faced with closed-ended questions or elicited one-word answers. Limited interactions were observed among students. In addition,a positive and strong relationship was established between accountable talk moves and the level of rigor in the observed lessons. Vaish (2008) examined Singaporean teachers’ discourse. The corpus included 273 English language lessons inPrimary 5 and Secondary 3 classrooms. According to results, the largest percentage of teachers’ talk time for both gradelevels was related to the curriculum-related teacher’s talk with teacher-fronted lessons being dominant. Teacherstypically used closed-ended questions and feedback moves were largely evaluative.

English teachers’ directives (including eight teachers regulative discourse comprising of 32 lessons in Grade 5) wereexplored by Liu and Hong (2009). Large use of imperatives (62.7%) compared to declaratives (26.1%) and interrogatives (11.3%) was reported. Moreover, procedural directives (62.6%) were used more than disciplinarydirectives (37.4%). In conclusion, the researchers argued that there was an asymmetrical power relation betweenteachers and students, with teachers possessing a more powerful social position than students. Furthermore, Shintani(2013) investigated teachers’ inputs and students’ outputs of the target language items in classroom discourse with thepurpose of examining language learning behavior. Accordingly, teachers’ elicitations (either requested or optional) werethe source of change in students’ replies (borrowed or self-initiated). As noticed above, most studies investigating teachers’ talk focused on science language teachers. Therefore, it seems rational to consider EFL teachers’ talk as a valuable resource of meaning making. To accomplish this mission, this study attempted to add to the previous literature by examining teachers’ talk in language classes from four Iranian EFL teachers.

Theme/rheme framework

This study drew upon theme/rheme distinction in Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) textual meta-functions. Theme in English is realized by the initial position in a clause and plays the roles of topic and rheme is what follows the theme (Flowerdew, 2013). A distinguishing feature of SFL suggested by Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) is concerned withmeta-function conceptualization. As suggested by Christie (2002), “the grammatical organization of all natural languages reflects the functions for which language has evolved in the human species” (p. 23). He believed that grammatical choices made in everyday discourses are negotiated and serve a particular function. Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) proposed three meta-functions including ideational, interpersonal, and textual. The ideational meta-function is concerned with knowledge representations; the interpersonal meta-function refers to the relationships between interlocutors and the textual meta-function is associated with message cohesion and coherence. As argued byChristie (2002), one purpose of text-driven grammatical analysis of English language using these meta-functions is to track how meaning is actualized and negotiated in a text. Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) maintain that, though these meta-functions are enacted simultaneously in a particular discourse, they can be analyzed separately.

Theme/rheme is a system of textual meta-function which has to do with how information in a clause and a text are packaged (Flowerdew, 2013). McCarthy (as cited in Flowerdew, 2013) provided the following fuller definition:

In English, what we what we decide to bring to the front of the clause (by whatever means) is a signal of what is to be understood as the framework within which what we say can be understood. The rest of the clause can be seen as transmitting what we want to say within this framework. Items brought to front-place we shall call the theme of their clauses. (p. 59)

Flowerdew also (2013) argued that theme is essential to spoken and written text construction. However, he claimed that“theme in spoken language has not received as much attention in the literature” (p. 75).

Analytical model

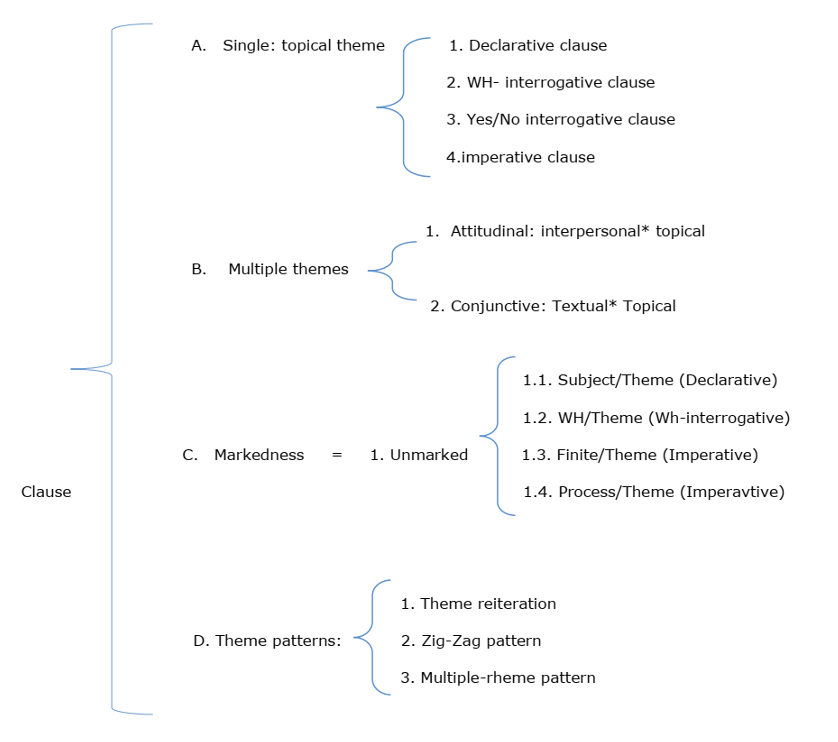

An analytical model (Figure, 1) was constructed based on Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) and Eggins’ (2004) theoretical frameworks and was verified by five applied linguistics professors in the field for its validity. This model represented a system of textual meaning in a clause. Theme is introduced by three major systems: choice of theme type which is divided into two categories: single theme and multiple themes, theme markedness which represents bothmarked and unmarked themes, and a system of theme patterning that is divided into three subcategories: themereiteration, Zig-zag pattern, and multiple-rheme pattern.

Single theme represents the topical theme of a clause. According to Eggins (2004), “when an element of the clause to which a transitivity function can be assigned occurs in the first position in a clause, we describe it as the topical theme” (p. 301). In a declarative clause, the topical theme consists of a subject (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013). In a Wh-interrogative clause, the topical theme includes a wh-element which begins that clause. In a yes/no interrogative clause, the finite element is considered as the interpersonal theme and the subject is the topical theme. Finally, the topical theme in an imperative clause consists of a predicator (Halliday & Matthiessen). In the theme/rheme system, the second category represents multiple themes. Multiple themes are divided into two subcategories. Here, the attitudinal subcategory is constructed from interpersonal and topical themes and the conjunctive subcategory is made up of textual and topical themes, respectively (Halliday & Matthiessen).

Markedness is the other sub-category in the theme/rheme system (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013). It is divided into marked and unmarked themes. According to Eggins (2004), unmarked themes are a typical/usual form of theme/rheme when, as an example, in a declarative clause, the subject occupies the theme’s position. Marked themes don’t follow simple theme rules concerning necessity for a topical theme. Eggins suggested that when a speaker selects marked theme, they are going to emphasize something in their interest. Theme patterning is the last category of this framework. Patterns of theme development make a significant contribution to the cohesion and coherence of a text (Eggins, 2004). Drawing on Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) and Eggins (2004), three patterns of theme developments adopted by the researchers are briefly described here.

A. Theme reiteration: One of the simplest ways to keep the text focused is to repeat the theme. Creative repetitionis an important way to keep cohesion (Eggins, 2004). In this pattern, the same element occurs for a short period oftime.

B. Zig-zag pattern: In this pattern, one element is introduced in the rheme and then the same element is used as theme of the next clause (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013).

C. Multiple-rheme pattern: In this pattern of theme development, the theme in a beginning clause introduces several elements in its rheme. Those elements are then picked up as themes in following clauses. The following figure provides patterns of theme development (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013).

Figure 1: Theme/rhyme system constructed based on Halliday and Matthiessen (2013)

Using Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2013) functional distinctions, the present study intended to fill this gap by providinga detailed analysis of EFL teachers’ discourses. For this purpose, the following research questions were proposed:

RQ1. How are simple themes incorporated in experienced and inexperienced EFL teachers’ talk?

RQ2: How are multiple themes incorporated in experienced and inexperienced EFL teachers’ talk?

RQ3. How are marked themes incorporated in experienced and inexperienced EFL teachers’ talk?

RQ4. What are the instances of theme patterning in the talk of experienced and inexperienced EFL teachers?

Method

Study design

In this study, the researchers used case study as the method of data collection. Despite some limitations, i.e., generalization, case studies enjoy noteworthy strengths such as “being strong on reality” and “speaking for themselves” (Cohen et al., 2000, p. 184). For the purpose of this study, teachers’ talk from four English language teachers was investigated in detail. Two experienced and two inexperienced EFL teachers holding MAs in teaching English as a foreign language agreed to participate in this study. All were female teachers so as to control for the gender variable. The inexperienced language teachers had less than two years teaching experience and the experienced ones had more than five years. Teachers ranged in age 25 to 29. In order to control teachers’ language proficiencies, all teachers were required to participate in a Test of Language by the Iranian Measurement Organization (TOLIMO) English test. TOLIMO is a standardized English proficiency test held bimonthly by Iranian Educational Ministry as the criterion for entering PhD courses in Iranian universities. All teachers had an MA degree in teaching English as a foreign language(TEFL). The participants in this study scored higher than 600 in TOLIMO test and based on the scoring criterion, theywere categorized as advanced language candidates.

Data collection

Before any discussion on data collection and analysis procedures, it should be noted that a pilot study was conducted ona smaller scale (one teacher). In this study, all teachers taught similar grammatical topics taken from similar book chapters. The units included simple past, present perfect and conditionals. Data were collected using video recordingsof six sessions for each teacher by an experienced cameraman. The teachers took their intact classes to participate in the study to avoid teaching new students and maintain students’ familiarity with their methodology.

Each teacher’s class was videotaped for ten sessions taking nearly five hours. Totally, the researcher collected 31 hours of videos for four teachers. These included 1,246 independent clauses. There were 541 simple sentences, 378 compound sentences and 218 complex sentences. The data was transcribed using the MAXQDA software. As the purpose of this study was to investigate the nature of pedagogic talk in the language classroom, nuanced details of teachers’ talk including pedagogical, disciplinary, and administrative issues were considered in data transcription without adding to or removing anything from it. It should be noted that an equal number of independent clauses for the experienced and inexperienced teachers were transcribed and analyzed. Before collecting data and making videos of the classes, informed consents were obtained from all the participating individuals.

Data analysis

The experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talk were compared for patterns of negotiating meanings. Independent and dependent clauses were considered as analysis units. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), “the clause is the central processing unit in the lexicogrammar – in the specific sense that it is in the clause that meanings of different kinds are mapped into an integrated grammatical structure” (p. 10). The researchers used typographic conventions suggested by Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) for the structural analysis. All data were coded by another PhD in applied linguistics who was trained to code samples of classroom discourse based on the systemic functiona lframework as shown in Figures 1 and 2. To investigate whether there was agreement between the coders, an inter-coder agreement test was used. The inter-coder agreement showed a coefficient of 0.86 using Cohen's kappa. To findsignificant differences in the use of various elements in teachers’ talk, the researchers used Chi-square test. The datawere analyzed using SPSS software.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive and statistical analysis for simple theme

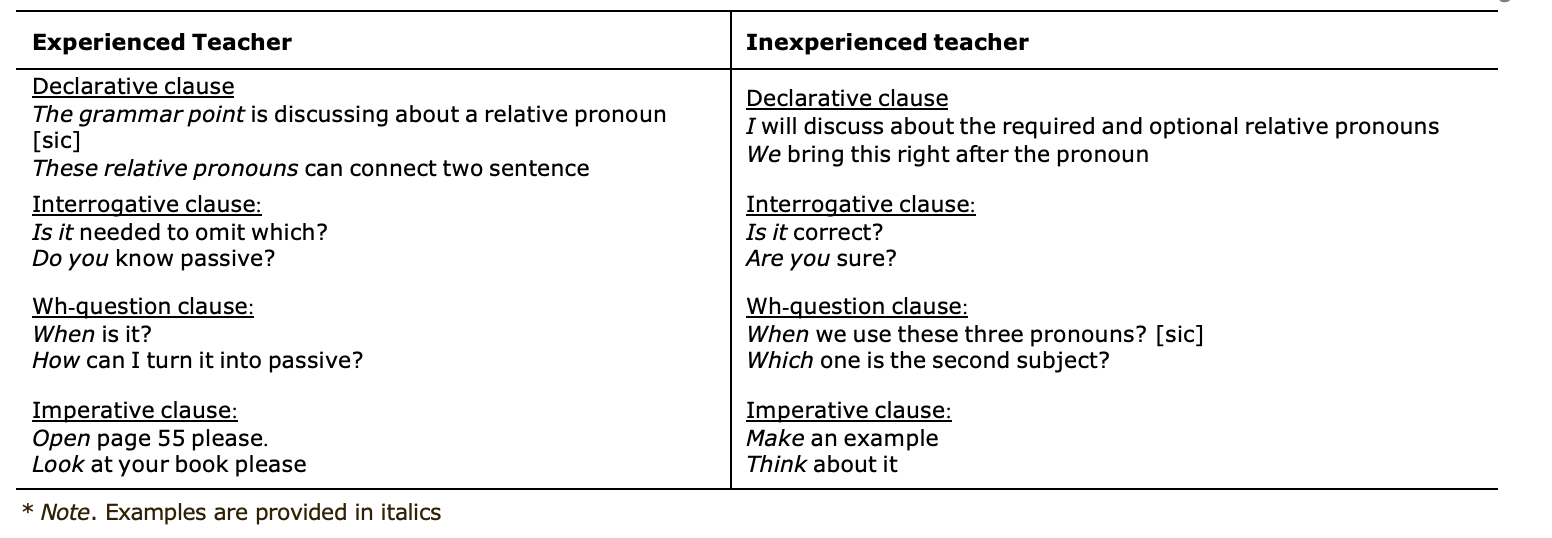

To answer the first research question, researchers investigated simple themes’ use in teachers’ talk, including declarative, interrogative, wh-question, and imperative clauses. The following Table provides examples of these in theexperienced and inexperienced teachers’ talk.

Table 1: Examples of simple theme subcategories for the experienced and inexperienced teachers

Regarding the declarative clauses, mostly, nominal phrases including grammatical categories such as active verb, passive verb, conditional, etc. were assigned as the topical theme. This represented old information in the theme so teachers provided new information in the rheme (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013). Declarative clauses are mainly used as a tool to state something. As illustrated in Table 1, teachers used the grammar point, these relative pronouns, I, and we as the topical themes in these declarative sentences. In these cases, they employed a declarative sentence to talk about content (grammar points) and procedure (how they are constructed). This was in line with Liu and Hong’s (2009) results that teachers used directives both for procedural and disciplinary purposes.

Questioning strategies in the language classroom are different from strategies in everyday life exchanges (Markee, 2000). Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) contend that interrogative clauses are constructed in the form of polarity “yes”and “no” clauses used to confirm aforementioned information. To search for the missing information, individuals canuse wh-clauses. This classification is in line with Long and Sato’s (1983) classification where display questions are exemplified in the form of interrogative questions and referential questions are embodied in terms of wh-questions. As expected, the majority of questions posed by the experienced and inexperienced teachers in this study were concerned with the subject matter. As indicated in the above table, Do you know passive? and How can I turn it into passive?, were questions used to elicit information from the students about some grammar points. This was in line with Vaish’s (2008) qualitative transcripts analysis, according to which, teachers’ questions were typically closed-ended and feedback moves were largely evaluative.

Moreover, imperative clauses can be used by the teachers to bring order to the language classroom. Investigation of teachers’ talk showed that both teachers used an imperative, open page 55 please or make an example, to tell the students what to do. Examples of different categories of simple themes used in the discourse of experienced and inexperienced teachers were provided above. The following Table provides descriptive results for simple themes.

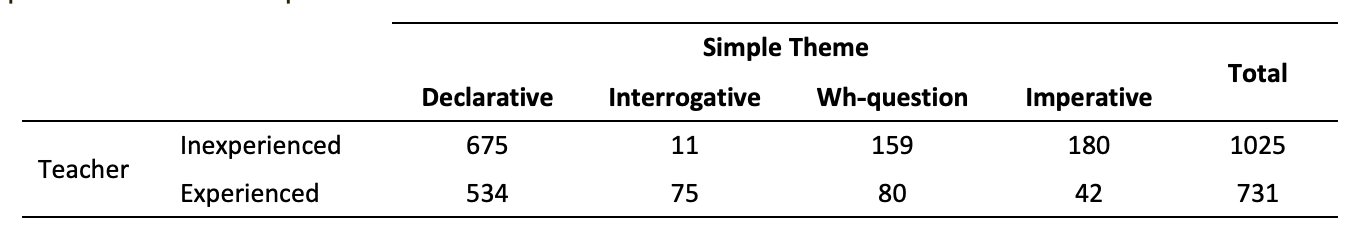

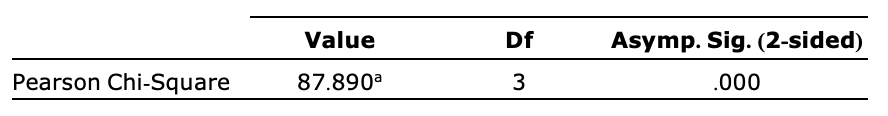

Table 2: Teachers’ simple theme descriptive statistics

As demonstrated in Table 2, the total number of simple themes used by the inexperienced teachers was higher than that of their experienced colleagues. The results showed that the inexperienced teachers used 675 declaratives, 11 interrogatives, 159 wh-questions and 180 imperatives while the experienced teachers used 534, 75, 80 and 42 clauses, respectively. Except for the interrogative clause, results showed higher use of other classes by the inexperienced teachers.

In this study, the teachers employed declarative clauses to explain a topic or answer a particular question. Higher use of them by the inexperienced teachers can show that they were devoting a higher share of classroom time to themselves explaining and discussing different topics. Based on these results, the inexperienced teachers were more interested in using wh-questions to pose new questions. This way, they required learners to provide an opinion or explain and clarify something. The experienced teachers’ inclination to use more interrogative questions is rooted in their desire to elicit leaners’ prior knowledge (showing that students know somethings about the topic at hand) and check comprehension (asking them to follow the discussion).

Stark differences in the use of imperative clause by the experienced and inexperienced teachers may provide us with the fact that these teachers practiced different strategies to bring order to their classroom. Higher use of imperatives by the inexperienced teachers may be indicative of their willingness to address leaners from a top down and authoritative stance. The following Table illustrates chi-square results for the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ use of simple themes. This test is used to compare frequencies of observations between the two groups. If the frequencies are not based on chance, the test will provide statistically significant results.

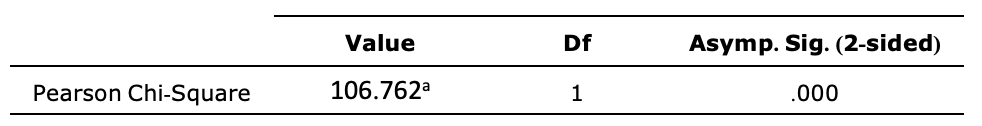

Table 3: Chi-square test

Results of the chi-square test for differences between the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ use of simple themes showed a significant difference (P<.05). This way, the researchers concluded that the frequency of simple themes used by the experienced and inexperienced teachers were different.

Descriptive and statistical results for interpersonal theme

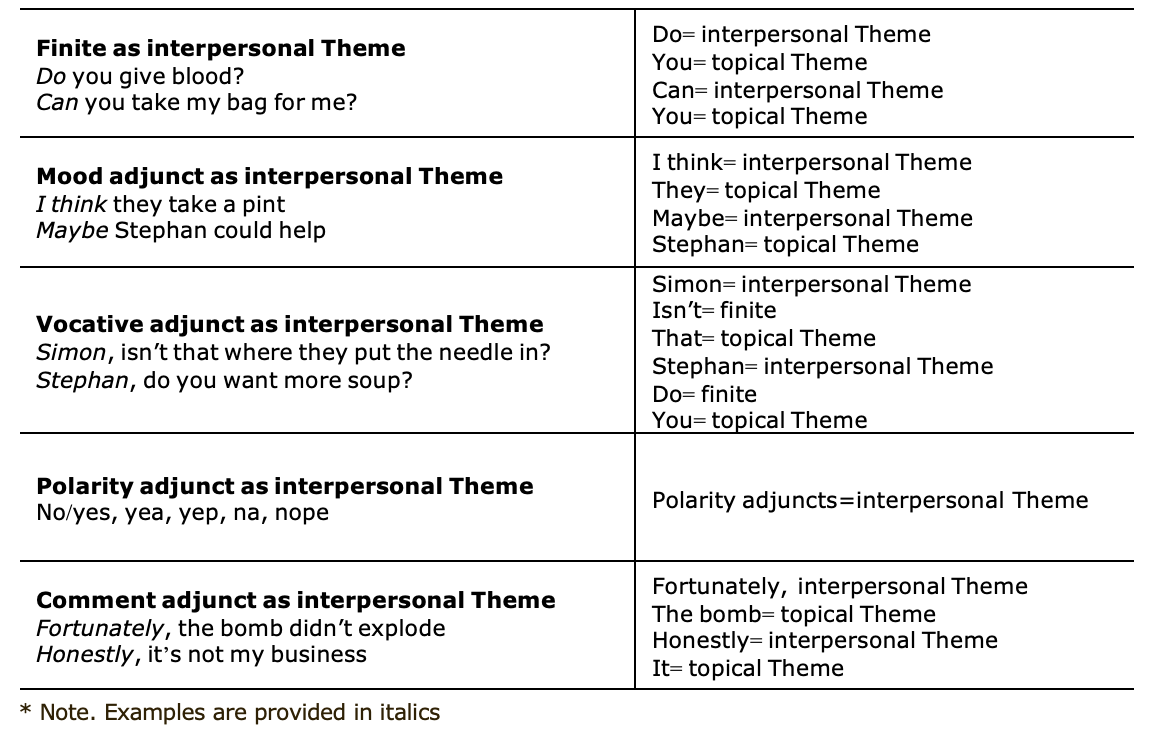

The researchers found examples of interpersonal themes in the talks of both groups of teachers. The interpersonal themes consist of finite, mode, vocative, polarity and comment adjuncts. Some examples are provided in the following Table.

Table 4: Examples of interpersonal themes used by the experienced and inexperienced teachers

Examples of finite as the interpersonal theme were provided in the last section when the researchers were explaining interrogative clauses. Polarity is the element used to express finiteness (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013). It is used to make a clause arguable by specifying positivity and negativity. Here, the researchers are concerned with the polarity adjuncts. Yes and No are used at the beginning of a clause to show positivity or negativity. As argued by Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), “in using a vocative, the speaker is enacting the participation of the addressee or addressees in the exchange.” (p. 159). The teachers used vocative adjuncts to address a particular person or to attract students’ attention. Mood “carries the burden of the clause as an interactive event” (Halliday, 1985, p. 77). In this analysis, modality refers to degrees of indeterminacy. Teachers used modality to provide some hedges on their discourse. The comment adjuncts “express the speaker’s attitude either to the proposition as a whole or to the particular speech function” (Halliday &Matthiessen, 2013, p. 129). They were used by teachers to show their attitude or evaluation of a particular subject.

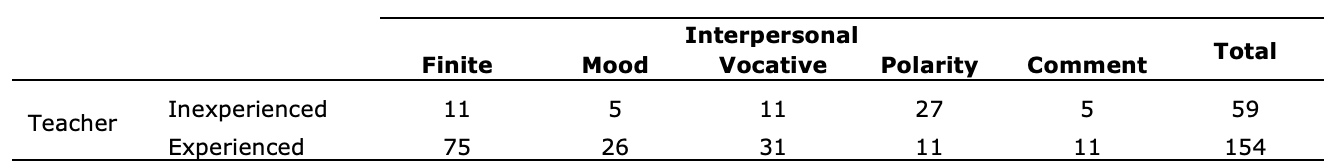

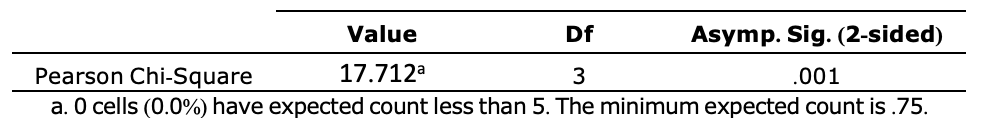

The cases reported here illustrated use of interpersonal themes by the experienced and inexperienced teachers. Descriptive statistics of these themes are provided in the following Table.

Table 5: Descriptive statistics for teachers interpersonal Theme use

Analysis of the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talk showed that the experienced teachers used more interpersonal themes than the inexperienced ones. The researchers used Chi-square test to investigate the differences between these teachers’ discourses. The result of chi-square test is provided below.

Table 6: Chi-square test

The results of chi-square test showed a significant difference in the teachers’ talk in terms of using the interpersonal themes (p<.05). According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), an interpersonal theme is used to specify a move in thediscourse, address somebody and express speaker or writers’ judgment or attitude. These are signs of interactivity in th ediscourse. Overall, the results supported the view that experienced teachers’ talk is more interactive than that of theinexperienced teachers. More use of interpersonal themes by the experienced teachers may also demonstrate complexity of their discourse compared to more use of simple themes by the inexperienced teachers.

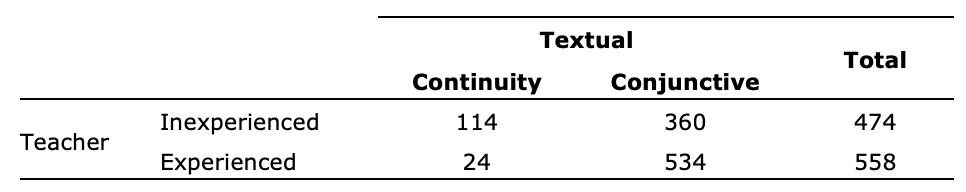

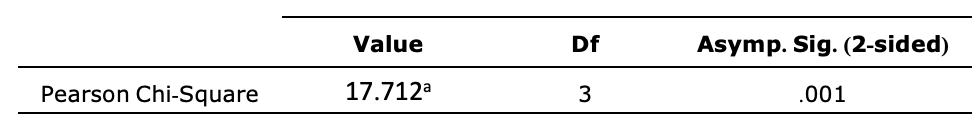

Descriptive and statistical analysis for textual themes

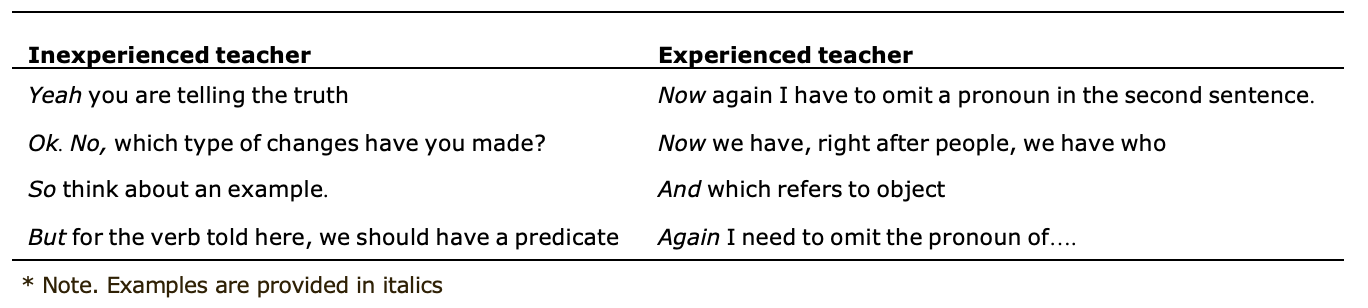

With respect to the use of textual themes by the experienced and inexperienced teachers, some differences were pinpointed. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), a textual theme comes before a topical theme and does not affect experiential meaning of a clause. The textual theme has two subcategories of continuity adjuncts and conjunctive adjuncts. The following Table provides some examples of these themes used by the experienced and inexperienced teachers.

Table 7: Examples of use of continuative and conjunctive adjuncts by inexperienced and experienced teachers

Table 7 shows that teachers used different types of linking words to make their talk coherent. Linking words are used to connect different elements in a text and as Rodrigues and Thompson (2001) and Jawahar and Dempster (2013) argued, they are necessary for text comprehension. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), conjunctive adjuncts expressed by cohesive conjunctions, “set up a contextualizing relationship […] between the clause as a message and some other (typically preceding) portion of text” (p. 157). Conjunctive adjuncts relate the clause to the preceding text and typically occur at the beginning of a clause (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2013). In the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talk, the most frequently used conjunctive adjuncts were and, so, but, now, because, then, if, for example, like, finally. As argued by Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), a continuative adjunct “is one of a small set of words that signal a move in the discourse: a response in dialogue, or a new move to the next point if the same speaker is continuing” (p.107). The most frequent continuatives used in teachers’ talk were yes, no, well, oh, now. Descriptive statistics for textual themes are provided below.

Table 8: Teacher textual theme cross tabulation

The results of descriptive statistics demonstrated that the experienced teachers used more textual themes than the inexperienced teachers. To examine this difference statistically, the researchers used chi-square test. The results are provided below.

Table 9: Chi-square test

The chi-square test results showed a significant difference between the experienced and inexperienced teachers in terms of textual themes use. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), textual themes are mainly employed to rhetorically or logically orient a clause within a particular discourse, set up a relationship with what precedes and follow and provide an anchorage for the clause in the discourse. According to the authors, use or more use of these elements can “complete the thematic grounding of a message” (p. 112). This way, the researchers argued that more use of textual themes by the experienced teachers showed a higher level of cohesion and coherence in their discourse which, in turn, may enhance students’ comprehension and learning of materials.

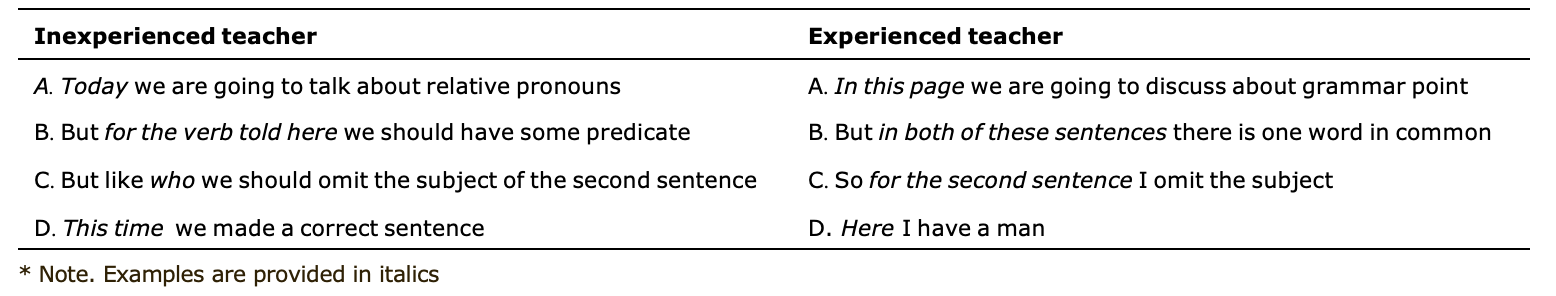

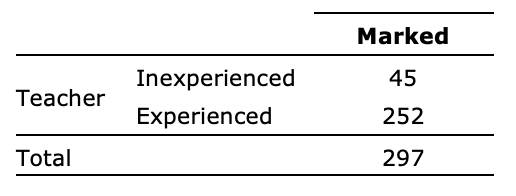

Descriptive and statistical analysis for marked themes

Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) maintained that a typical clause is made up of a subject, an interrogative, a wh-question or an imperative as its topical theme. These are the examples of unmarked themes. When one of these elements is not positioned as the theme of a clause, everything which occupies this position is considered to play the role of a marked theme. According to the authors, marked themes are used to emphasize a particular element in a clause. Table 9 delineates some cases of marked themes used by the teachers.

Table 10: Examples of marked themes used by the teacher

Marked themes can be utilized in every stage of teachers’ discourse. For instance, consider Example A in the experienced teachers’ talk. It occurs at the beginning of class time and the teacher asked for students’ attention as shewas starting to teach. In this case, she started the clause with in this page to indicate the lesson’s commencement. Like the experienced teachers, one of the inexperienced teachers started a clause with the time adjunct, today, to begin the lesson and ask for students’ attention. According to Eggins (2004), when a marked theme is incorporated in a text, the speaker or writer intents to highlight a specific point. For instance, in the above examples, the inexperienced teachers highlighted time (Example A), context (Example B), subject (Example C) and time (Example D). On the other hand, theexperienced teachers emphasized location (Example A), subject (Example B), subject (Example C) and condition (Example D). Descriptive statistics for marked themes are provided below.

Table 11: Descriptive statistics for marked themes

As illustrated in Table 10, the number of marked themes used by the experienced teachers is more than the number for the inexperienced teachers. To examine if the difference is statistically significant or not, the researchers used a Chi-square test. The results are provided below.

Table 12: Chi-square test

The difference between the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talk regarding the providence of marked themes was statistically significant. Eggins (2004) argued that writers and speakers can use marked themes to add coherence and emphasis to their discourse. Therefore, as higher use of marked themes was detected in the experienced teachers’ talk, the researchers concluded that their talk was more coherent and they paid more attention to their audience.

Patterns of theme development in the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ discourse

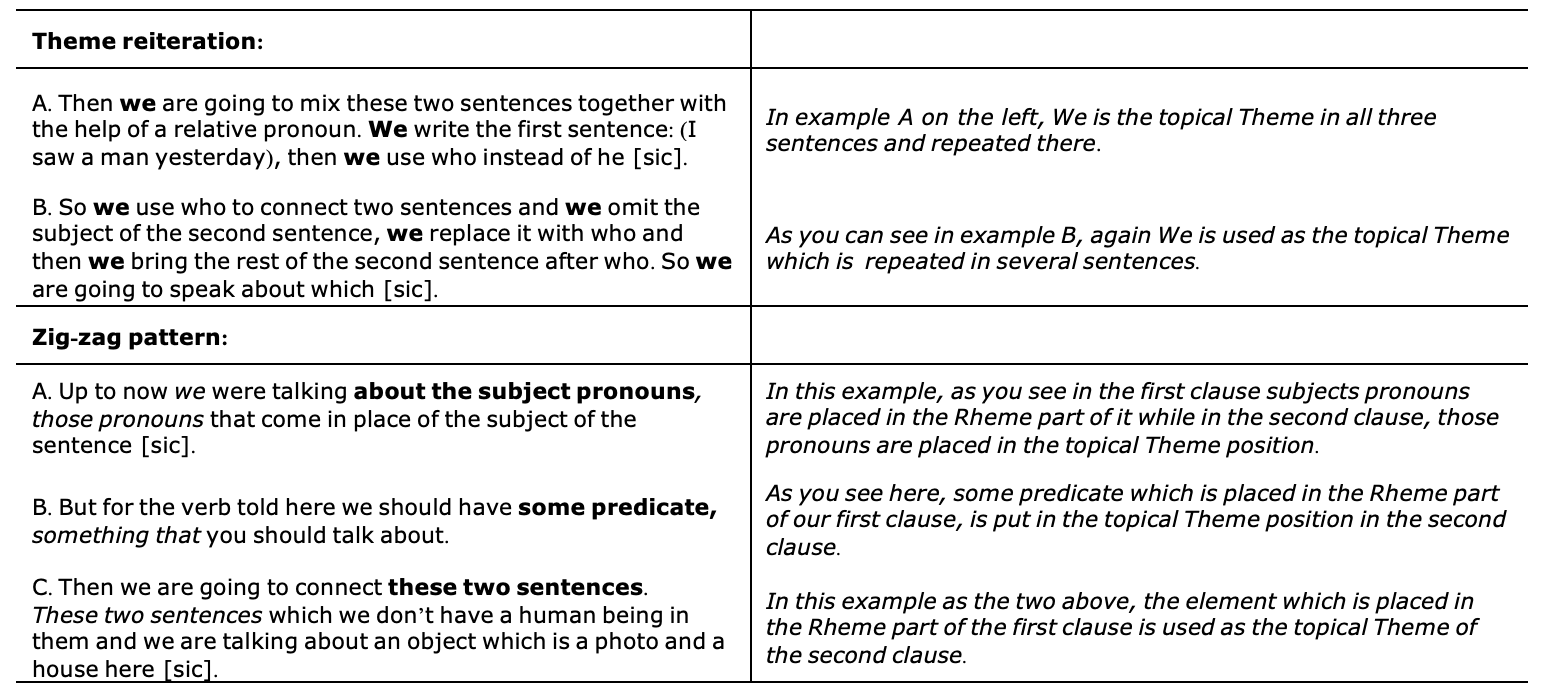

Theme is considered as an element which provides texture. According to Halliday (1985), textual meaning “is relevance to the context: both the preceding and following text and the context of situation” (p. 53). Various theme development patterns have been suggested by different authors to deliver a text which is coherent. In this study, based on Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) and Eggins (2004), the researchers investigated occurrence of three theme patterns in discourses of the experienced and inexperienced teachers. Table 12 provides examples of theme patternings. Descriptive analysis of results for the inexperienced teachers showed that they used reiteration (N= 81) and zig-zag (N= 60) patterns in their talk to negotiate their meaning. Concerning the inexperienced teachers, the researchers were notable to find examples of multiple-rheme patterning in their discourse. Some examples illustrating applications of these two theme types by the inexperienced teachers are provided below. These results may be important as showing that the experienced teachers’ talk in the language classroom is more complicated than the inexperienced teachers’ talk.

Table 13: Examples of use of theme reiteration and zig-zag pattern by inexperienced teachers

According to Eggins (2004), theme reiteration is used to keep a text cohesive. In this way, the writer or speaker repeats the theme he or she has proposed in the previous clauses in order to focus on one element and bring it to the fore. For example, consider example B in reiteration section in the inexperienced teachers’ talk. In this example, the teacher is explaining linking two sentences using relative pronouns. The teacher used, we, for a short while in consecutive clauses to focus on action, i.e., doer, of linking two sentences and steps which should be taken by learners to link these two sentences. This was in line with Halliday & Matthiessen’s (2013) argument that, in conversations, personal pronouns tend to be preferred as the theme. Therefore, by selecting a personal pronoun, teachers can enhance texts’ cohesiveness by focusing on one element in a text and repeating that element in a particular section of the text. Eggins (2004) argued that repetition can increase cohesiveness of a text. However, there is a problem with theme reiteration. As suggested by Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), a large percent of theme reiteration in a text may lead to a monotonous and boring flow of discourse. For this purpose, the inexperienced teachers used a zig-zag pattern erratically to avoid thismonotony. Although the number of theme reiterations used in the inexperienced teachers’ discourse outnumbered the zig-zag pattern, this sporadic use of zig-zag pattern could improve dynamicity of their talk.

The zig-zag pattern was used by the inexperienced teachers to talk about an element which was introduced in the rheme, i.e., new information, of the previous sentence. For example, consider example A in Table 12. The teacher was talking about subject pronouns for the class. In the first sentence, the phrase, subject pronoun, is placed in the rheme. However, in the second clause, the teacher moved an equivalent for the subject pronoun, namely those pronouns, to the theme position so as to change the discussion’s focus and highlight it. In this way, the inexperienced teachers remained to the point on the topic of interest. These patterns also occurred in the experienced teachers’ talk. As far as reiteration and zig-zag patters are concerned, both groups of teachers benefited from them. In spite of that, there was a noteworthy difference between the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talks which should be taken into account. The researchers were able to find examples of multiple-rheme patterning in discourse of the experienced teachers. The examples are provided below.

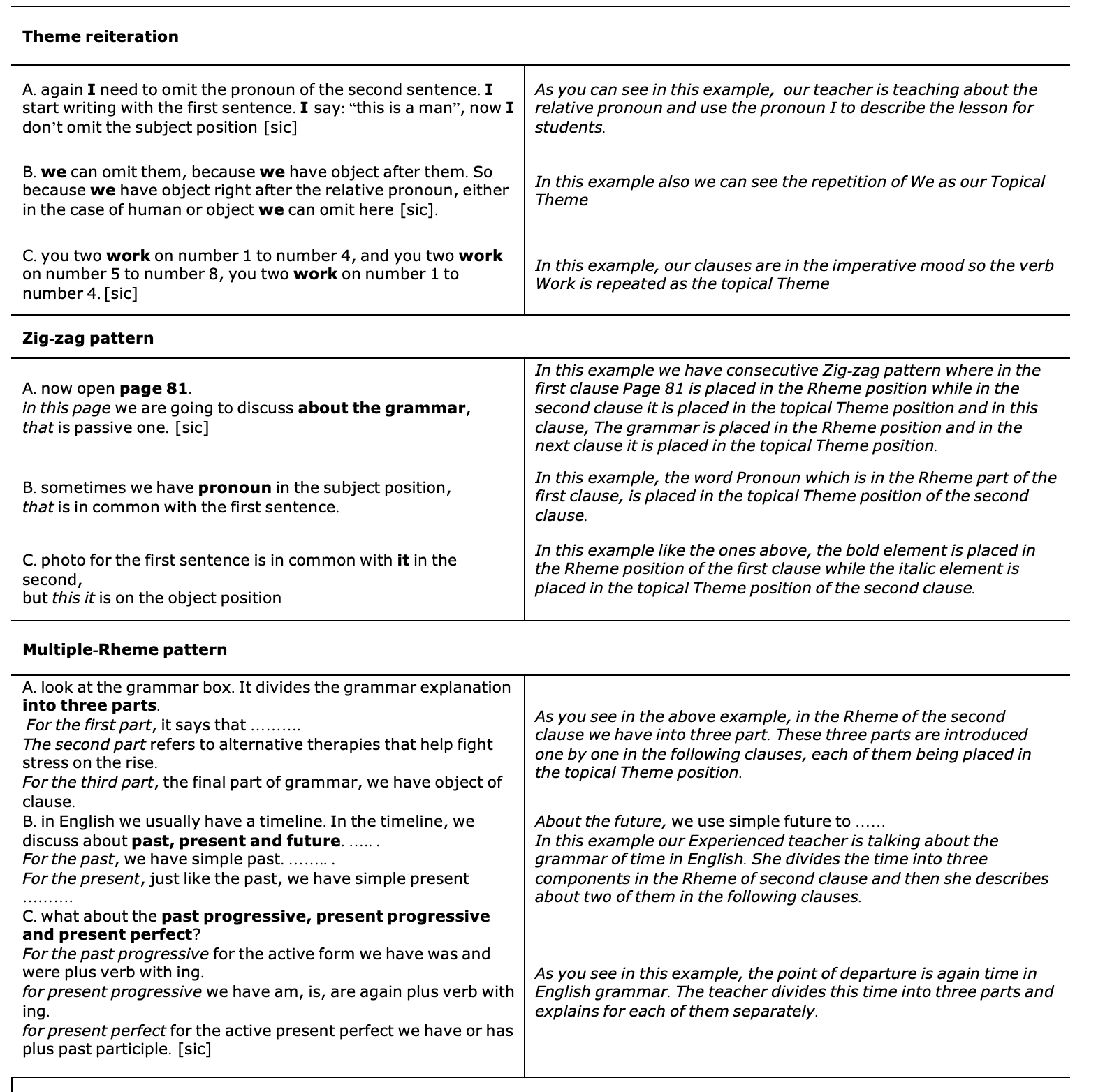

Table 14: Examples of use of Theme reiteration by experienced teachers

The experienced teachers used reiteration (N= 138), zig-zag (N= 80) and multiple-rheme pattern (N= 38) in their discourse. These results indicate that the experienced teachers’ talk was more complicated that the inexperienced teachers’ talk in both quantity and quality. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2013), the most compelling element in development of a text is its thematic organization. They argued that for cohesion and coherence, a text should follow a type of theme patterning that is recognized by its reader or listener. The experienced teachers used multiple-rheme pattern in their discourse. This pattern can be used to talk about a topic which is constructed from various branches. Therefore, the speaker or writer can introduce main topics in the theme of beginning sentences and enumerates its branches in the rheme. Then, the rheme will be divided into different themes in the following sentences or paragraphs to provide a sense of unity for the whole text.

This model of theme patterning can be very applicable in teaching English grammar as most grammatical topics in English are made up of different branches (for example, when a teacher intends to teach conditional sentences in English, he or she can define conditional sentences in the theme and then introduce different types of conditional sentences in the rheme). In the experienced teachers’ talk in this study, the researchers found many examples of multiple-rheme patterns for teaching tenses (present, past, future), conditionals (type 1, type 2, type 3), progressives,etc. This can be related to Martin and Rose’s (2007) concept of hypertheme and macrotheme. They argued that we canexpand the level of theme development towards the whole paragraph by assigning a broad theme to the first sentence and describing it in the next sentences (hypertheme). According to Martin and Rose (2007), hypertheme institutes the field of discourse, i.e., its subject matter. Ravelli (2004) demonstrated that in a writing class, texts produced by learners will be more convincing as far as, “they can predict where they are going, flag where they are and reiterate where they have been” (p. 104).

On the other hand, they argued that a speaker or writer can assign a theme as a topic of discourse and talk or write about it in details (macrotheme). The results of using multiple-rheme patterns by the experienced teachers may show that their talk was more dynamic and less monotonous compared to the inexperienced teachers’ talk. Moreover, this may show that the experienced teachers had a more comprehensive mental image of what they were going to teach and were able to provide material coherently for their learners. Further, these results may confirm that the experienced teachers, consciously or unconsciously, were aware of various styles of developing and presenting a subject matter.

Conclusion

This study provides some insights on the nature of experienced and inexperienced EFL teachers’ talk in grammar classes. The results indicated that, in general, the experienced and inexperienced teachers’ talks were constructed from different functional structures. Moreover, these results showed that experience may play a determining role in EFL teachers’ teaching practice. Moreover, the results demonstrated that the experienced teachers’ talk was more elaborate than the inexperienced teachers’ talk. The results can be summarized as follow:

- The inexperienced teachers used simpler themes than the experienced teachers.

- The experienced teachers used more interpersonal themes compared to the inexperienced teachers

- The experienced teachers used more textual themes compared to the inexperienced teachers

- The quality and quantity of themes patterns were richer in discourse of the experienced teachers compared to the inexperienced teachers.

Implications of the study

The results of this study may have the following implications:

- Inexperienced teachers’ talk may be constructed from simpler elements compared to experienced teachers’ talk during teaching of grammar in anEnglish class

- Experienced teachers’ talk may be more interactive and dynamic in a language class compared to inexperienced teachers’ talk

- Experienced teachers enjoy higher cohesion and coherence in their talk compared to inexperienced teachers

- Experienced teachers may be able to provide their instructional material in a less monotonous and more systematic way compared to inexperiencedteachers

- Experienced teachers may have a more thorough and well-established picture of the materials they are intending to present to learners

This study has some implications for classroom discourse practitioners.

First, experience should be considered as a leading factor in the process of teaching language skills, grammar, in this case. Using data from experienced language teachers’ classroom talk, teacher educators can help prospective and novice teachers to develop their practice in the language classroom.

Second, it should be noted that as the experienced and inexperienced teachers used different elements in theirdiscourses to negotiate meaning, they have socialized students differently in the process of learning. Therefore, students of experienced and inexperienced teachers should be expected to hold different understandings of a particular subject and this important fact should be considered in their evaluations.

Then, discourse analysts can utilize SFL as an effective tool for providing a rich and comprehensive description of language teaching and learning processes. SFL can help us to gain a better understanding of the relationship between teachers’ language use and learners’ learning. In addition, curriculum developers can use data from experienced and inexperienced teachers’ discourse to provide learners with different models of presenting materials. Teacher educators can provide some guidelines for language teachers on how to produce a more cohesive and coherent discourse as more control of theme development may enhance efficiency of teaching and learning processes. Besides, this study highlighted the importance of discourse-based approaches for language teaching.

Limitations of the study

This study has its own limitations. Although we did not aim at generalization, future studies can target a larger group of participants so as to generalize the findings. Language teacher experience is not clearly defined in the literature. Future researchers can select teachers with different language teaching backgrounds to provide a more elaborate conceptualization of experience. Last but not the least, accompanying analytical data by data from teachers’ cognition can strengthen and validate obtained results and conclusions.

References

Christie, F. (2002). The development of abstraction in adolescence in subject English. In M. J. Schleppegrell & M. C. Colombi (Eds.).Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages: Meaning with power. Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). Routledge.

Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics (2nd ed.). Continuum.

Flowerdew, J. (2013). Discourse in English language education, Routledge.

Foster, P. (1998). A classroom perspective on the negotiation of meaning, Applied Linguistics, 19(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.1.1

Halliday, M. A. K. (1985). Introduction to functional grammar. Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2013). Introduction to functional grammar (4th ed.). Routledge.

Jawahar, K., & Dempster, E. R. (2013). A systematic functional linguistic analysis of the utterances of three South African physical sciencesteachers. International Journal of Science Education, 35(9), 1425-1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2013.785640

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Liu, Y, & Hong, H. (2009). Regulative discourse in Singapore primary English classrooms: Teachers’ choices of directives. Language andEducation, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780802152812

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook ofsecond language acquisition (pp. 413-468). Academic Press.

Long, M. H., & Sato, C. J. (1983). Classroom foreigner talk discourse: Forms and functions of teachers’ questions. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long(Eds.), Classroom oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 268–85). Newbury House.

Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in L2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20(1), 51–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226319800103X

Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2007). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause (2nd ed.). Continuum.

McCarthy, M. J. (1991). Discourse analysis for language teachers. Cambridge University Press.

Markee, N. (2000). Conversation analysis. Erlbaum.

Markee, N., & Kasper, G. (2004). Classroom talks: An introduction. The Modern Language Journal, 88(4), 491-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0026-7902.2004.t01-14-.x

Molinari, L., Mameli, C., & Gnisci, A. (2013). A sequential analysis of classroom discourse in Italian primary schools: The many faces of the IRF pattern. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 414-430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02071.x

Moser, J., Harris, J., & Carle, J. (2012). Improving teacher talk through a task-based approach. ELT Journal, 66(1), 81-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr016

Ravelli, L. J. (2004). Signalling the organization of written texts: Hyper-themes in management and history essays. In L. J. Ravelli & R. A. Ellis(Eds.), Analysing academic writing: Contextual framework (pp. 104–130). Continuum.

Rodrigues, S., & Thompson, I. (2001). Cohesion in science lesson discourse: Clarity, relevance and sufficient information, InternationalJournal of Science Education, 23(9), 929-940. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690010025076

Rymes, B. (2008). Classroom discourse analysis: A tool for critical reflection. Hampton Press.

Shintani, N. (2013). The effect of focus on form and focus on forms instruction on the acquisition of productive knowledge of L2 vocabulary byyoung beginning-level learners. TESOL Quarterly, 47(1), 36–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.54

Shintani, N., & Ellis, R. (2014). Tracking ‘learning behaviours’ in the incidental acquisition of two dimensional adjectives by Japanese beginnerlearners of L2 English. Language Teaching Research, 18(4), 521–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168813519885

Vaish, V. (2008). Interactional patterns in Singapore’s English classrooms. Linguistics and Education, 19(4), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2008.05.007

Wolf, M. K., Crosson, A. C., & Resnick, L. B. (2005). Classroom talk for rigorous reading comprehension instruction. Reading Psychology, 26(1), 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710490897518

Young, R. F., & Nguyen, H. T. (2002). Modes of meaning in high school science. Applied Linguistics, 23(3), 348-372. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/23.3.348