Introduction

Discussions on the role of culture in English language teaching (ELT) have been a topic of interest among many ELT researchers and professionals for many years. It is believed that culture is an integral part of the learning of a second language (L2) (Tomalin, 2008); therefore, teaching a language requires the teaching of its culture as well (McKay, 2004; Tajeddin & Teimournezhad, 2015). In addition, the widespread use of English as a means of communication worldwide has changed its status as an international language (Crystal, 2003; McKay, 2018), leading to a change in the ELT professionals’ opinion about the accepted cultural aspects of the English language. McKay (2004) explains that the features of English, as an international language, are no longer limited to those of the version spoken by its native speakers. In other words, she believes we cannot refer to the language native English speakers use as the correct or main form of English. Therefore, the culture of those native English countries can no longer be considered the culture of English. According to Seidlhofer (2005), this view toward English has changed its status from English as a Foreign or Second Language (EFL/ESL) to English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). ELF is strongly connected to a more general phenomenon which recognizes English as an International Language (EIL), in which English is spoken by people from various cultural and historical backgrounds all over the globe (Jenkins, 2006; McKay, 2002). EIL is not a property of the countries where English is spoken natively, and it has its position and features depending on the setting in which it is formed and used (Kachru, 1992).

Since English is nowadays viewed as an international language, the selection of the cultural content that go es into ELT textbooks has turned into a challenge as well. Several researchers believe that since English is a language used throughout the globe, it is now a language with no country. For this reason, the content of the English course books should not be limited to the culture of the Anglosphere and should also be representative of the other countries where English is also learned and spoken (Putra et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2011; Yuen, 2011). Ndura (2004) highlights the sensitivity of cultural content selection by stating that textbooks “play the role of cultural mediators as they transmit overt and covert societal values, assumptions and images” (p. 143). She also explains that this cultural representation profoundly impacts how students form opinions about themselves and the world around them.

Realizing the importance of international cultural representation in English textbooks, many researchers have conducted discourse analyses of English textbooks to check their representation of non-native cultures (Hillard, 2014; Shin et al., 2011; Tajeddin & Pakzadian, 2020; Tajeddin & Teimournezhad, 2015). Considering the global view toward English as ELF, it is expected that English course books should take an unbiased approach toward utilizing cultural content representing different parts of the world. However, research has shown that certain cultural groups, mainly the native English ones, are dominant over others in English textbooks (Rashidi et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2011; Tajeddin & Teimournezhad, 2015). Therefore, it is concluded that further research on international cultural representation, or non-native representation, in English course books is needed to raise English teachers’ and students’ awareness of the cultural aspects of the materials they utilize.

This study critically examines the content of the Touchstone series, an English textbook series used by a significant number of EFL/ESL learners all over the world. This examination is based on Kachru’s (1992) three circles of World Englishes to determine the cultural representativeness of the countries in which English is spoken. The Touchstoneseries was chosen after a thorough search of the website of five well-known English institutes in Iran revealed the series constituted the main course books for those institutes. The five institutes have over 130 branches throughout Iran. Previously very few studies have investigated the Touchstone series’ cultural content (e.g., Hosseinzadeh et al., 2022; Köksal & Ulum, 2021; Rezai et al., 2021;). This study investigates the reading passages, dialogues, images, and audio materials used in the series to show the cultural representations therein. The findings of this study could be beneficial for ELT material developers and curriculum designers who wish to produce course books with more internationally representative cultural content and for English teachers since it can help them understand how non-native cultures are represented in these series and if there is a need for extra-curricular international cultural materials. The present study intends to find an answer to the following question:

How are the inner circle, outer circle, and expanding circle countries' cultures represented in the Touchstone textbook series?

Literature Review

The issue of culture in language teaching has been a topic of interest to applied linguists for the last few decades. The advocates of the sociocultural theory believe that language is learned through communication which takes place among individuals in contexts, each of which includes specific cultural aspects (Shin et al., 2011). Accordingly, language learning ought to prepare learners to be efficient communicators in the cultural settings they plan to enter once they have learned the language. Hence, ELF learners must be trained for communication in the cultural contexts which they will most probably face, not the culture of just a few countries.

It is essential to define culture before investigating its impact on language and language learning and teaching. Kramsch (1996) explains that culture can be defined from at least two different perspectives: humanities and social sciences. Regarding the view in humanities, Kramsch explains that culture makes use of arts, literature, social institutions, etc., to highlight how a social group represents itself and others. Furthermore, culture can be defined in relation to its social aspects. As Brislin (1990) stated, “culture refers to widely shared ideals, values, formation, and uses of categories, assumptions about life, and goal-directed activities that become unconsciously or subconsciously accepted as ‘right’ and ‘correct’ by people who identify themselves as members of a society” (p. 11). Taking both of these definitions into account, one can conclude that texts and even other types of content can carry cultural values as they are the means through which culture-based norms, perceptions, behaviors, and ways of thinking and acting, in general, are represented. There is also a need for ELT specialists to clarify the relation between culture and language, which can affect language teaching and learning.

McKay (2004) sheds light on the crucial role of culture in ELT by clarifying how culture is injected into language teaching. She explains that the teaching of culture is inevitable in teaching the semantics, pragmatics, and rhetoric of English. Regarding semantics, she argues, culture must be taught because the meaning of many lexical items cannot be fully learned if the cultural and historical background of the word is not learned (e.g., Christmas pie or Big Three). Secondly, McKay (2004) describes how integrating culture in pragmatics is evident when the teacher plans to teach speech acts such as responding to a compliment. These speech acts take different forms in different cultures, and one must decide according to which culture the speech acts will be taught. In other words, if everyone learns the speech acts as practiced in inner circle countries, using such acts in outer or expanding circle countries could cause them trouble. Thirdly, the effect of culture on rhetoric can be seen by reading the text written by authors from different cultural backgrounds, reflecting the patterns of their thought and speech (McKay, 2004). Therefore, culture plays a significant role in choosing a particular rhetorical pattern to teach to EIL learners. Moreover, Tomalin (2008) emphasizes the vital role of culture in language learning as he regards it as the “fifth skill”, alongside reading, listening, speaking, and writing.

Having learned about the undeniable importance of culture in ELT, one might ask about the categories or contexts from which cultural content can be adapted to be put in English textbooks. In order to answer this question, it is essential to have a better understanding of Kachru’s (1992) division of the English-speaking world into the inner circle, outer circle, and expanding circle countries. As McKenzie (2008) explained, each of these circles includes countries where particular features and functions of English are spread and utilized. The inner circle countries are those in which English is used as the first and official language, for instance, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. The term “outer circle countries” refers to the ones in which the spread of English resulted from colonization. Therefore, English is their second language. Kachru (1992) mentions that these countries “represent the institutionalized non-native varieties (ESL) in the regions that have passed through extended periods of colonization” (p. 356). In countries from the expanding circle, English is learned as and an EFL; thus, it is used in international interactions for business purposes, diplomatic purposes, and so forth. As English is an international language, it is expected that English textbooks include cultural content representing all three circles without any bias toward the inner circle countries. As it is proven that the number of non-native English speakers exceeds the number of native English speakers (Hanashiro, 2016; McKay, 2004), one might find it reasonable that the culture of expanding and outer circle countries should even be over-represented compared with inner circle countries.

Therefore, it is not surprising that many studies have investigated the intercultural representation in English textbooks (Hillard, 2014; Putra et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2011; Tajeddin & Teimournezhad, 2015; Tajeddin & Pakzadian, 2020). Shin et al. (2011) conducted a content analysis of seven English course book series in their study. They reported that despite a proportional cultural diversity in each book, the culture of inner circle countries still dominates the cultural content of textbooks. An interesting factor that the authors took into account is the level of cultural presentation in the course books under study to show that the cultural content is knowledge-oriented or communication-oriented. However, the type of content which was investigated in this study was not mentioned. Obviously, there might be a difference in the cultural representativeness of texts, audio materials, and visual contents of a textbook, yet the researchers did not state if their results were drawn by analyzing all kinds of content or just a specific type of content. In another study by Hilliard (2014), the hidden ideologies alongside the perspectives and cultural information existing in the textual, visual and audio materials included in four English course books were examined from a pedagogical perspective. The results, not surprisingly, indicated that these four books

…include a limited scope of topics, under-represent a variety of minority groups in the culture represented, contain a limited range of accents in their audio material, generally lack in-depth cultural information, and contain a paucity of cultural activities targeting the development of students' intercultural communicative skills. (p. 238)

Thus, one can conclude from these findings that even in this day and age, textbooks are traditionally biased, which could lead to the assumption that the decisions behind material development are also biased.

Rashidi et al. (2016) took a rather different approach in investigating the cultural representativeness of English textbooks in inner, outer, and expanding circle countries. They selected three books, written and published in one of these three circles of countries, and explored their first language (L1), L2, international, and neutral cultural representativeness. The results of this study indicate that although all books had more L1 cultural representation compared to the other types, the ones written in the outer and expanding circle countries included more international cultural material than those written in an inner circle country. Furthermore, while there were no signs of culturally neutral content in the inner circle textbook, the other two contained some items from this category. Hence, this study demonstrates a bias against international cultural content in inner circle countries’ course books. The researchers mainly focused on the differences in the intercultural representativeness of the ELT textbooks written in different circles of countries. However, since the book chosen from an inner circle country was published in 2010, before the two other books which were published in 2011 and 2013, there is an assumption that the factor of time might have had an impact on the results. Moreover, as this topic has drawn a lot of attention during the last decade, there is a need for continued investigations on more recently-published books. Basing their research on this assumption, Naji Meidani and Pishghadam (2013) analyzed four textbooks published in different time periods in English-speaking countries and found out that the books written in earlier times encompassed a much higher dominance of inner circle countries’ cultural representation compared with the ones published more recently.

Putra et al. (2020) scrutinized the representation of cultures and intercultural interaction in three English textbooks published in Indonesia. Contrary to the sole dominance of inner circle countries in the studies mentioned earlier, the cultural content in these books manifested the Indonesian culture alongside the culture of English-speaking countries. The fact that the results showed very little inclusion of international cultural content means that the lack of international cultural representation is an issue in most English course books. Published in Indonesia, those course books were written to help learners become international civilians who are capable of communicating with people from different countries. However, the books might have gone through a process of localization to be more feasible for the users. Hence, studies on more globally used course books are needed to shed more light on how high stakeholders make decisions regarding the intercultural representativeness of the content in ELT textbooks.

Tajeddin and Pakzadian (2020) examined three EFL textbooks written in 2005, 2008, and 2014. The results of their analysis were in line with the findings of previous studies and showed a preference in ELT textbooks for the culture of inner circle countries. However, they find that despite the dominance of the culture of the Anglosphere, two of the books written in 2005 and 2008 include more content referring to the outer and expanding circle countries. The contradictions in the results of these different studies prove that there is a need for more research in this field to determine how course book developers approach the intercultural content of the materials they design.

None of the analyses mentioned above were done on the Touchstone series, however. Köksal and Ulum (2021) performed a content analysis on this specific series and supported the findings of their study through a qualitative analysis of the interviews with Turkish students who had used those books. They, too, claim that the Touchstone series favors the culture of native English-speaking countries. The researchers chose nine themes, names, personalities, nationalities, languages, history, celebrations, cuisines, stereotypes, and clothing, and then counted the items that are representative of each circle of the country in each theme. However, upon further examination of the data presented in Köksal and Ulum’s (2021) article, we (the researchers of the current study) found out that the inner circle countries were over-represented only in three themes. We also noted that the percentages of representativeness between inner and expanding circle countries under ‘history’ were very close. Although the number of items representing inner circle countries’ cultures under this theme was very high, we believe the occurrence of English ‘names’ might not be an appropriate indicator of cultural representativeness. For instance, there might be a family in the USA who has lived there for generations and follows all American cultural norms. However, based on a matter of taste, they might choose an ‘un-American’ name for their children. Therefore, there is a need for a more thorough analysis of the Touchstoneseries to find out how these course books represent the culture of Kachru’s three circles of countries.

Methodology

Corpus

The purpose of this study is to investigate the cultural representativeness in the Touchstone series using Kachru’s (1992) influential and widely used World Englishes model, which divides the English language speakers/users into three different circles of countries: the inner, outer, and expanding. The ultimate aim of the study is to reveal the hidden ideology, regarding cultural representativeness, in English teaching materials. The second edition of the Touchstoneseries, written by McCarthy et al. (2014), is widely used in many language schools and institutes in Iran, and teachers have expressed positive attitudes toward the feasibility of these books in Iranian settings (Hashemi & Borhani, 2012). This series consists of four books, each of which contains 12 units. Each unit is divided into four lessons, that focus on specific language items and skills. For instance, the third lesson of each unit is planned to focus on conversational strategies and includes a dialogue that reflects the theme and linguistic items which will be worked on in that lesson. Similarly, the fourth lesson of each unit is designed to assist the students in improving their reading and writing abilities. Hence, the fourth lesson of each unit in all of this series contains a reading passage.

The data for this study were the reading comprehension passages, dialogues, photos and illustrations, and audio materials available in this series. Each book includes 12 reading passages, printed in the last lesson of each unit. In this series, conversations and dialogues abound through different parts of the units; therefore, it would have led to disorganization and confusion if the researchers had tried to analyze all the conversations from different lessons, which are designed and used for various purposes. Thus, the conversations at the beginning of every third lesson were selected for data analysis to keep the data organized and avoid confusion. We used the conversations in the third lesson because they are all particularized for teaching conversational strategies. Therefore, these conversations are referred to several times during the lesson and behold great importance. Accordingly, the audio material of these conversations was analyzed as well. Moreover, the photos and illustrations used in all the lessons and units were considered for their intercultural representation.

Analytical framework

To answer the research question, Kachru’s (1992) division of the English-speaking world into three circles was adopted. The reason behind choosing this framework was that it does not focus on any specific countries and accounts for many countries according to their position in the English-speaking world. However, the analysis of the data based on this categorization can give a clear image of how the cultures of different countries are represented in these commercial textbooks. This framework has been used in empirical studies for purposes similar to the objectives of this paper (Rashidi et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2011)

Data collection

The data was gathered from the passages and conversations by taking into account each word, phrase, or topic which is representative of a culture: words or phrases such as names of cities, foods, festivals and holidays, rituals, and customs.. For example, a text about Christmas or the appearance of the word Christmas pudding was counted as an item representing inner circle countries. Accordingly, the pictures and illustrations were studied and put into different categories depending on the culture they represented. For instance, an illustration of an Indian family, or a photo of the Taj Mahal, is considered representative of an outer circle country, which is India. The audio material was also analyzed regarding the application of native or non-native accents.

Due to the lack of convincing evidence to support the judgment about the cultural references of all the images in these course books, only the visual items whose reference could be evidently determined were considered. For example, the references of some of the images, mostly the ones referring to a particular building or landscape, were traceable. In addition, in some instances, the book itself provided the readers with the specifics of the displayed images, such as the nationality of the people in the photos or the location of the depicted landscapes. In addition, all the photos which included a person of color were considered representative of expanding circle countries in the study. However, pictures with no traceable reference or explanation were not considered. Consequently, many items were excluded from this analysis.

Data analysis

To conduct the data analysis, the two researchers in this study first categorized the representative items in the four sources of data (i.e., the reading comprehension passages, dialogues in the third lesson of each unit, images, and audio materials from the mentioned dialogues) into three categories, each referring to one of the circles. Then, all the items were counted and their sum was put into a table. It is worth mentioning that prior to the analysis, the researchers practiced analyzing two sample units to get sufficiently familiar with the classification procedure. Furthermore, in order to determine the reliability of the analysis, two other raters (both TEFL professors with extensive research backgrounds in cultural studies) were asked to ascertain the decisions the researchers had made in assigning the data to different cultures; agreements between the two judges were assessed through Cohen’s Kappa coefficient(κ), a statistic which measures inter-rater agreement for categorical items. The agreement index varied from 0.80 to 0.95, indicating a high level of inter-rater reliability. According to Cohen (1960), Kappa results are to be interpreted as follows: values ≤ 0 as indicating no agreement and 0.01–0.20 as none to slight, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.41– 0.60 as moderate, 0.61–0.80 as substantial, and 0.81–1.00 as almost perfect agreement. If there was a disagreement about the category to which an item belonged, the judges discussed the issue until an agreement was reached. For instance, if only 26 words and phrases in the reading passages of the first book were representative of inner circle countries, while 60 items represented the outer circle countries and no lexical item representative of the expanding countries was found, the numbers in the first row would be 26, 60, and 0 respectively.

Results

To identify how the cultures of the three circles of countries were represented in the Touchstone series, the reading passages of the fourth lesson of each unit, the conversations in the third lesson of each unit, the audio material of those conversations, and the visual items throughout the whole units were analyzed. The series has four textbooks, and from each textbook five units were randomly selected to be analyzed.

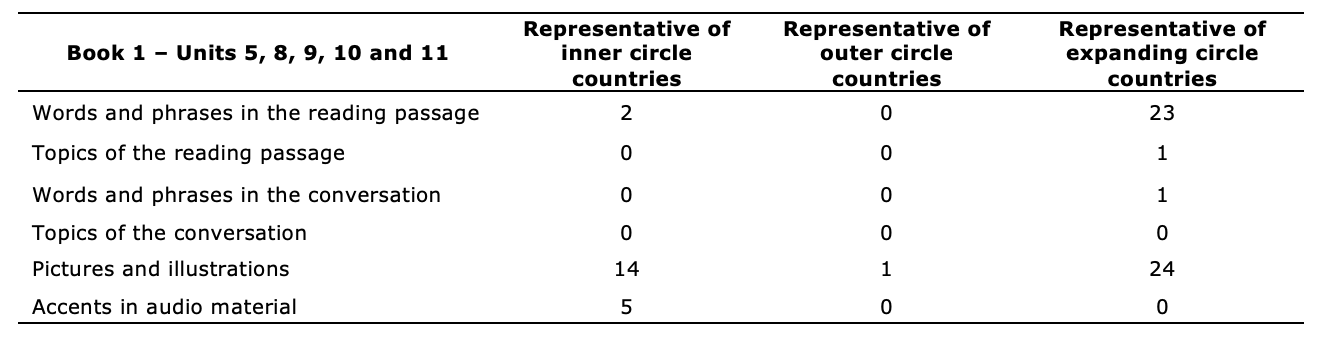

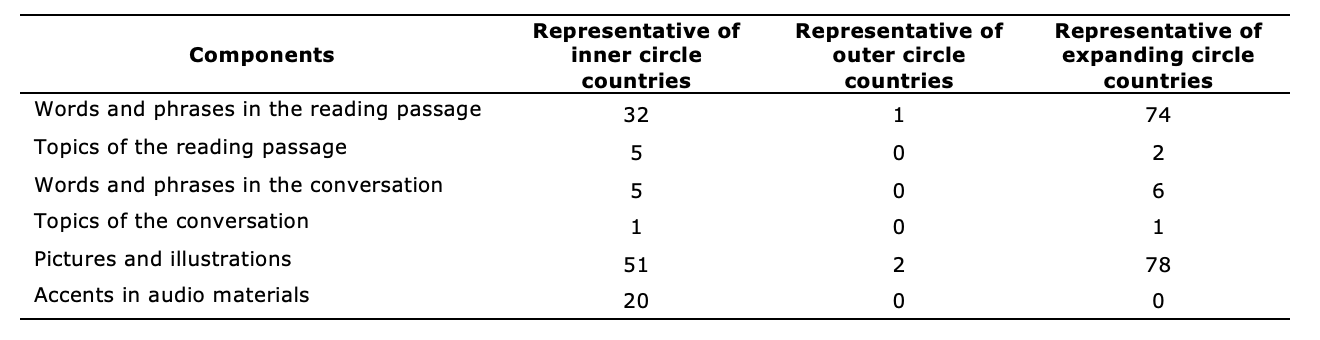

In Table 1, the number of culturally representative items in the randomly selected units of Touchstone 1 is shown. It is important to mention that the fourth lesson of the first four units did not include a reading passage due to the level of the book, so the data were obtained from Units 5 to 12.

Table 1: The frequency of culturally representative items in Touchstone 1

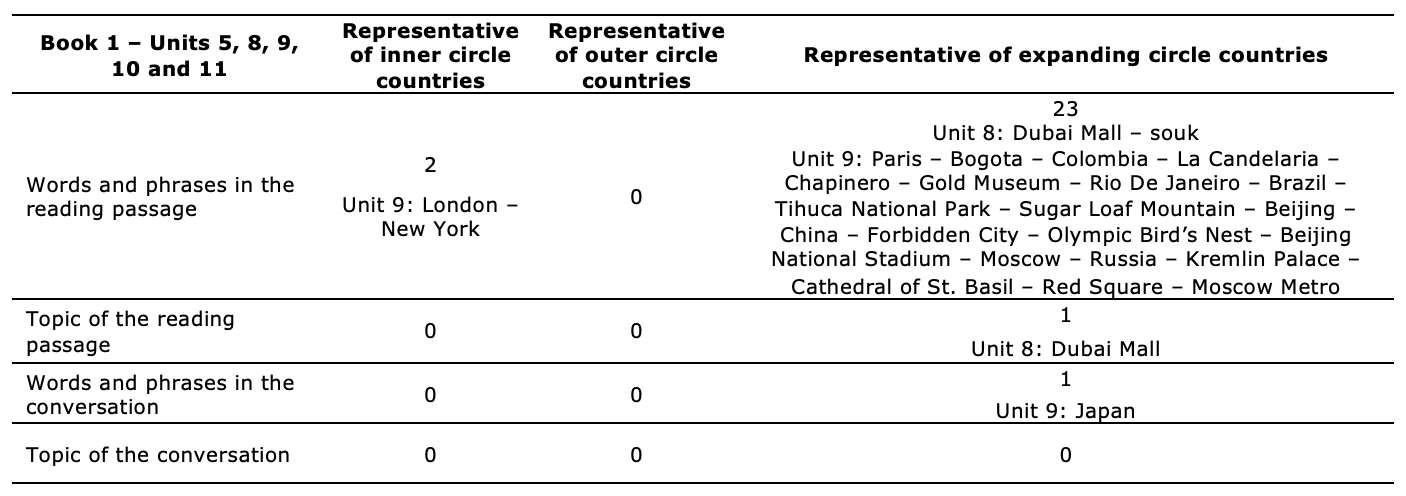

As shown above, many sections of the units did not include culturally representative items, and mostly culturally neutral topics and materials were used in those lessons. Words and phrases such as Dubai Mall and souk (Unit 8), Paris, Bogota, Colombia, La Candelaria, Chapinero, Gold Museum, Rio De Janeiro and Brazil (Unit 9) can be mentioned as some of the culture-related items in the reading passages. These items clearly referred to expanding circle countries. Table 2 shows the culturally representative lexical items and topics existing in the five selected units of Touchstone 1.

Table 2: Culturally representative lexical items and topics existing in the five selected units of Touchstone 1

As explained earlier, it was observed that not all the lessons of these units include cultural items. For instance, none of the conversations in the randomly selected units of Touchstone 1 had a topic referring to cultures of a specific circle.

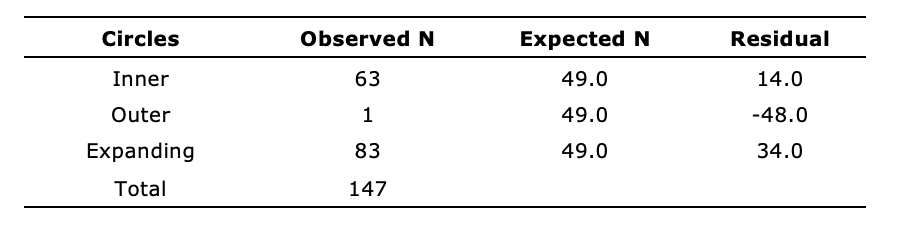

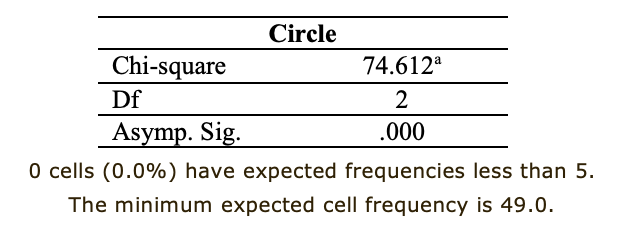

A chi-square test was run to find out if there was a significant difference between the observed and expected number of items representing the cultures of each circle country. The results of the test (Tables 3 & 4) indicated that the culturally representative items in the Touchstone 1series – excluding the visual content – were not equally distributed among the three circles of countries. The expanding circle was significantly over-represented compared to the other two circles. In addition, the outer circle countries were poorly represented.

Table 3: Frequency of items representing cultures of each circle countries

Table 4: The Chi-square test statistics

The analysis of the four books in this series showed that the content of the books mainly revolved around the culture of the inner circle and expanding circle countries, displaying no or very little representation of the outer circle countries.

Another noteworthy point is the results of the analysis of the audio materials. Detecting the nuances which distinguish between nonnative accents is a task that needs great expertise and has to be done by an accent specialist. Therefore, the researchers only tried to differentiate the native accents from the non-native ones without specifying the exact country to which the accents belonged. To the surprise of the researchers, the results of the analysis showed that all the audio materials under investigation were in native accents and eventually, there was no need to differentiate between the accents of the outer circle and expanding circle countries. The findings of the analysis of all four books of the Touchstone series are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: The frequency of culturally representative items in Touchstone series

The Table above shows the frequency of culturally representative items through all the books of the Touchstone series. It can be seen that most of the cultural materials were found in the passages in the fourth lesson of each unit and the visual items throughout all of the units. As mentioned before, outer circle countries were given little attention in this series, and most of the materials were related to the other two circles. Another finding revealed by the analysis of the content in this series was the low number of culturally representative items in general. This finding can be attributed to the authors and publisher’s apparent tendency to use culturally neutral content in many cases.

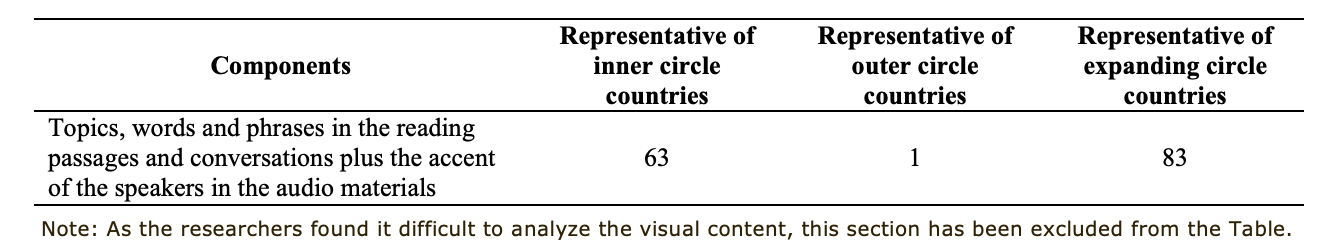

The data presented in Table 5 show the frequency of intercultural representativeness in different sections of the books. Table 6 shows the sum of all representative items in all sections of the selected units. Surprisingly, in general, more content was dedicated to the expanding circle countries in comparison with the other two circles.

Table 6. Frequency of culturally representative items in the reading passages, conversations, and the audio materials of the Touchstone series

Discussion

It is widely acknowledged that English is currently the world’s lingua franca (bridging language) through which millions of people with different linguistic backgrounds interact and exchange information. Some researchers (e.g., Clyne & Sharifian, 2008; Crystal, 2003; McKay, 2002; Pecorari, 2018) suggest that the number of those who speak English as an L2 surpasses that of those who speak it as their L1. Many believe that the global spread of English has helped intercultural understanding and international communication (Erling, 2002; Gashi, 2021; Graddol, 2006; McKay & Bokhorst-Heng, 2008; Salih & Omar, 2021). However, there are researchers (e.g., Babaii & Sheikhi, 2018; Majhanovich, 2013; Pennycook, 1994; Phillipson, 1992) who think that the spread has led to the continuation of the socio-political, cultural, or economic ideologies of the inner circle countries. Phillipson (1992), for instance, argues the global spread of English is in line with and helpful to English-speaking nations’ political and economic intentions to impose their power on other countries. He believes that this is a threat to many countries’ cultural ideals, lifestyles, and even languages.

Perhaps one of the best sites to look for the ideological underpinnings of ELT is in the textbooks (published mainly by American and UK companies) that are used worldwide to teach the language. ELT textbooks do not just carry language knowledge, but also social, cultural, political, and moral values (Feng, 2019; Gray, 2002; Gray & Block, 2014; Setyono, & Widodo, 2019; Shardakova & Pavlenko, 2004). Therefore, these textbooks can help learners develop certain attitudes and worldviews. Howard and Dedo (1989) mention that course books are capable of promoting the idea of accepting power and considering it natural. According to Fairclough (1995), writers of textbooks have to decide “what is included and what is excluded, what is made explicit or left implicit, what is foregrounded and what is backgrounded, what is thematized and what is unthematized, what process types and categories are drawn upon to represent events, and so on” (p.104). The idea that course books are neutral and present an objective description of the world is thus no longer accepted (Babaii, 2021; Hodge & Kress, 1993; Howard & Dedo, 1989; Van Dijk, 1998).

This study analyzed the intercultural representativeness in the Touchstone series, a globally-distributed ELT textbook series. It has long been discussed that the learning of a language has strong ties with the learning of its culture (Tajeddin & Teimournezhad, 2015). However, the state-of-the-art belief about English views this language regardless of its native-speaking countries and considers English as an international language (McKay, 2004). Realizing the significance of this point, the authors and publishers of ELT textbooks are encouraged to include the culture of countries from all three circles in Kachru’s (1992) division (Putra et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2011; Yuen, 2011). The findings of this study expose the extent of the cultural content in the Touchstone series according to their reference to the inner, outer, and expanding circle countries. This investigation proves that these books represent the culture of both inner and expanding countries, with a minor dominance of the latter. However, outer circle countries were culturally under-represented in this series.

The literature on content analysis with regard to the cultural representativeness of textbooks abounds with research finding ELT materials guilty of cultural bias favoring the English-speaking nations (i.e., inner circle countries). For instance, Shin et al. (2011) studied seven ELT textbooks. Despite a proportional diversity in each book, they claimed the cultural content of these books is dominated by the inner circle countries. In line with that study, Hilliard’s (2014) research indicated the same dominance of the culture of the countries where English is spoken as the mother tongue. The current study, however, contradicts the findings of the above investigations. The analysis of the verbal, visual, and audio materials of five randomly selected units of each of the four textbooks shows that the expanding circle countries have greater representativeness than the other two circles. One reason for this contradiction might be the fact that Touchstone (2nd ed.) was published in 2014, quite a long time after the course books analyzed in the literature review of the present article. This assumption, however, needs scientific support and empirical evidence to be proven. Hence, more studies on the recently published ELT textbooks and their approach toward intercultural representation are needed.

One obstacle the researchers faced during this analysis was the traceability of the visual content. Unfortunately, it is not possible to trace all photos, pictures, and images existing in the books to their culture. Therefore, the researchers had to ignore many of the visual items and only make judgments about those which could be evidently traced to the culture of a circle. All the analyses were checked with two other raters to avoid misclassification.

The findings of this study and other similar studies may be of great value to the publishing industry as they may raise the awareness of the ELT textbook publishers to implement and include intercultural materials which are fairly distributed among different country circles. Under-representation of different cultures can harm the students in several ways. A straightforward instance of the harm that may be caused in this way is related to the students who are planning to utilize their language skills in international businesses or for any other purposes in the outer circle countries. The abundance of cultural materials mainly representing the Anglosphere, which consequently leads to an under-representation of the culture of other circles of countries, may create the false impression that English is solely associated with that specific culture. Hence, they might not have enough communicative competence or false cultural presuppositions when they enter the setting where they want to use their language skills.

In addition to curriculum designers and the people who make major educational decisions, ELT teachers may benefit from this line of research and consider the cultural impact of the material they provide their students with. Thus, if a teacher finds the course books under-representing a specific culture, s/he can compensate for this lack of data by bringing extra material to the class. Having stated the significance of the impact of this line of work on the ELT community, it is highly recommended that more research be done on course books to promote and encourage the idea of fair cultural representativeness in ELT textbooks.

Conclusion

Canagarajah (1999, 2002) argues that in this global operation, the Anglo-American countries hold a monopoly over the non-Anglo-American ones since the flow of ideas regarding ELT emanates from the core English-speaking countries, and the developing countries rely heavily on western-generated products. This unidirectional exchange, he notes, has led many educators in the developing communities to accept core-produced methods, materials, training programs, and research journals, among other things, as “the most effective, efficient, and authoritative for their purposes” (p. 135). This situation has locked the core English-speaking countries and countries where English is a second or foreign language into an unequal power relationship. Pennycook (1994) also writes that for much of its history, ELT has been subject to the heavy “evangelical zeal” of the core or the inner circle countries. The inner circle countries have exported their theories, methods, approaches, materials, and books to the outer and expanding circle countries often with doubtful relevance to the sociological, educational, and economic contexts of those countries.

ELT textbooks, as a cultural artifact, may represent the values and norms of a particular culture. As a result, bias creeps in and, due to the superiority of one social actor over others, the pedagogical outcomes of instructional materials might become inappropriate. Within ELT, the use of UK and US published textbooks and course materials promoting either a British or an American standard of English, respectively have enjoyed unequaled supremacy in ELT for decades (Gray, 2002). Alpetkin (1993) claims that those internationally published textbooks, which often use target language culture elements (British or American cultures) to present English, are likely to interfere with the natural tendency of EFL learners’ culture-specific cognition.

The literature has shown most ELT textbooks tend to over-represent the inner circle countries and neglect the culture of countries of other circles. However, the findings of the present study revealed that the majority of the intercultural content in the Touchstone series was dedicated to the expanding circle countries followed by the culture of the inner circle countries. Consequently, outer circle countries were found to be significantly under-represented in this series.

Considering the findings of this study, it is concluded that writers of ELT textbooks might have started to change their approach to representing intercultural content; however, this is only a claim which needs to be proven by more studies on other recently published textbooks. In addition, the lack of representation of outer circle countries’ cultures is an issue that the writers and publishers of the Touchstone series need to address. Moreover, the findings of this analysis and other studies in this field can raise teachers’ awareness of intercultural representation in different textbooks. The findings are whether they need to provide their classes with extra intercultural content to compensate for the lack of such materials in textbooks.

References

Alptekin, C. (1993). Target-language culture in EFL materials. ELT Journal, 47(2), 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/47.2.136

Babaii, E. (2021). ELT textbook ideology. In H. Mohebbi & C. Coombe (Eds.), Research questions in language education and applied linguistics (pp. 689-693). Springer Texts in Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79143-8_120

Babaii, E., & Sheikhi, M. (2018). Traces of neoliberalism in English teaching materials: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(3), 247-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2017.1398671

Brislin, R. W. (Ed.). (1990). Applied cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 14). Sage Publications. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483325392

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2002). Globalization, methods and practice in periphery classrooms. In D. Block & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching (pp.134-150). Routledge.

Clyne, M., & Sharifian, F. (2008). English as an international language: Challenges and possibilities. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 31(3), 28-1. https://doi.org/10.2104/aral0828

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

Erling, E. J. (2002). ‘I learn English since ten years’: The global English debate and the German university classroom. English Today, 18(2), 8-13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026607840200202X

Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. Edward Arnold.

Feng, W. D. (2019). Infusing moral education into English language teaching: An ontogenetic analysis of social values in EFL textbooks in Hong Kong. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(4), 458-473. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1356806

Gashi, L. (2021). Intercultural awareness through English language teaching: The case of Kosovo. Interchange, 52, 357-375.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-021-09441-5

Graddol, D. (2006). English next (Vol. 62). British Council.

Gray, J. (2002). The global coursebook in English language teaching. In Block, D. & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching (156-167). Routledge.

Gray, J., & Block, D. (2014). All middle class now? Evolving representations of the working class in the neoliberal era: The case of ELT textbooks. In N. Harwood (Ed.), English language teaching textbooks (pp. 45-71). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hanashiro, K. (2016). How globalism is represented in English textbooks in Japan. Hawaii Pacific University TESOL. Working Paper Series, 14, 2-13.

Hashemi, S. Z., & Borhani, A. (2012). Textbook evaluation: An investigation into Touchstone series. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 2(12), 2655-2662. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.12.2655-2662

Hillard, A. D. (2014). A critical examination of representation and culture in four English language textbooks. Language Education in Asia, 5(2), 238-252. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/14/V5/I2/A06/Hilliard

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. R. (1993). Language as ideology (Vol. 2). Routledge.

Hosseinzadeh, M., Heidari, F., & Choubsaz, Y. (2022). A comparative analysis of the cultural contents and elements in international and localized ELT textbooks. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 10(1), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijscl.2021.246790

Howard, T., & Dedo, D. (1989). Cultural criticism and ESL composition. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English, Baltimore, MD. (ERIC Document Reproductive Service No. ED 317062)

Jenkins, J. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching world Englishes and English as a lingua franca. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 157-181.https://doi.org/10.2307/40264515

Kachru, B. B. (1992). Teaching world Englishes. In B. B. Kachru (Ed.), The other tongue: English across cultures (2nd ed.) (pp. 355-365). University of Illinois Press.

Köksal, D., & Ulum, Ö. G. (2021). Analysis of cultural hegemony in Touchstone EFL course book series. The Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 21(1), 131-141.

Kramsch, C. (1995). The cultural component of language teaching. Language, culture and curriculum, 8(2), 83-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908319509525192

Majhanovich, S. (2013). How the English language contributes to sustaining the neoliberal agenda. In S. Majhanovich & M.A. Geo-JaJa (Eds), Economics, aid and education. The world council of comparative education societies. SensePublishers, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-365-2_6

McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching English as an international language: Rethinking goals and perspectives. Oxford University Press.

McKay, S. L. (2004). Teaching English as an international language: The role of culture in Asian contexts. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 1(1), 1-22.

McKay, S. L. (2018). English as an international language: What it is and what it means for pedagogy. RELC Journal, 49(1), 9-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217738817

McKay, S. L., & Bokhorst-Heng, W. D. (2008). International English in its sociolinguistic contexts: Towards a socially sensitive EIL pedagogy. Routledge.

McKenzie, R. M. (2008). The complex and rapidly changing sociolinguistic position of the English language in Japan: A summary of English language contact and use. Japan Forum, 20(2), 267-286.

Ndura, E. (2004). ESL and cultural bias: An analysis of elementary through high school textbooks in the Western United States of America. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 17(2), 143-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310408666689

Naji Meidani, E., & Pishghadam, R. (2013). Analysis of English language textbooks in the light of English as an International Language (EIL): A comparative study. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 2(2), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.163

Pecorari, D. (2018). Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). In P. Seargeant, A. Hewings, & S. Pihlaja (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language studies (pp. 199-211). Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. Longman.

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Putra, T. K., Rochsantiningsih, D., & Supriyadi, S. (2020). Cultural representation and intercultural interaction in textbooks of English as an international language. Journal on English as a Foreign Language, 10(1), 163-184. https://doi.org/10.23971/jefl.v10i1.1766

Rashidi, N., Meihami, H., & Gritter, K. (2016). Hidden curriculum: An analysis of cultural content of the ELT textbooks in inner, outer, and expanding circle countries. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1212455

Rezai, A., Farokhipour, S., & Azizi, Z. (2021). A comparative study of gender representation in Iranian English high school books and TouchStone Series: A critical discourse analysis. Iranian Journal of Comparative Education, 4(4), 1459-1478. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijce.2021.262839.1283

Salih A. A., & Omar L. I. (2021). Globalized English and users’ intercultural awareness: Implications for internationalization of higher education. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 20(3),181-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/20471734211037660

Seidlhofer, B. (2005). English as a lingua franca. ELT Journal, 59(4), 339-341. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci064

Setyono, B., & Widodo, H. P. (2019). The representation of multicultural values in the Indonesian ministry of education and culture-endorsed EFL textbook: A critical discourse analysis. Intercultural Education, 30(4), 383-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2019.1548102

Shardakova, M., & Pavlenko, A. (2004). Identity options in Russian textbooks. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 3(1), 25-46. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327701jlie0301_2

Shin, J., Eslami, Z. R., & Chen, W.-C. (2011). Presentation of local and international culture in current international English-language teaching textbooks. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 24(3), 253-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2011.614694

Tajeddin, Z., & Pakzadian, M. (2020). Representation of inner, outer and expanding circle varieties and cultures in global ELT textbooks.Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 5(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-020-00089-9

Tajeddin, Z., & Teimournezhad, S. (2015). Exploring the hidden agenda in the representation of culture in international and localized ELT textbooks. The Language Learning Journal, 43(2), 180-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.869942

Tomalin, B. (2008). Culture-the fifth language skill. Teaching English, 48(1), 130-141.

Van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. Sage.

Yuen, K.-M. (2011). The representation of foreign cultures in English textbooks. ELT Journal, 65(4), 458-466. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq089