Introduction

The teaching and learning process rapidly transformed from a traditional classroom into an online classroom setting due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All the educational institutions were forced to shut down physical activity and to shift the learning process to using various applications like WhatsApp, Zoom, and Google Meet. The online learning concept was not new, and the existence of high-speed internet access and the advances in technologies supported the flexibility of the teaching and learning process to supplement the traditional learning methods (Wang et al., 2019). Some of the main goals of online learning are to deliver the quality of learning by decreasing the cost of delivery and increasing education access to the masses (Hamidi & Chavoshi, 2018; Panigrahi et al., 2018). Online learning is generally beneficial for teachers and students, as the learning process can be conducted anywhere and anytime at their own pace. Some studies have also mentioned that the students’ perception of online learning was mostly favorable (Alqurashi, 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2019).

However, it should be noted that before the pandemic, online learning courses were mostly conducted as supplemental activities. The number of online academic meetings in schools and universities was mostly lower than the conventional meetings. Thus, the pandemic caused a radical change, as the learning process was strictly conducted ‘online only.’ This disruption caused chaos among the teaching practitioners, as there was no previous strategic preparation and planning for the sudden implementation of distance learning. More importantly, the most important factor was ensuring that the delivery was acceptable from the students’ perspective, as they were the main participants. The suggested shifting from an offline to online classroom caused panic for students since not all the students were familiar with educational technology in an online setting (Dong et al., 2020).

In English for Specific Purposes (ESP) classes, these rapid changes influenced the students’ routines and strategies in the learning process. One of the main concerns was the students’ ability to adapt to the changes in teaching strategies from offline to online classes. Learning a language has expectations for students to communicate and to perform direct interaction with the teachers and their peers. However, the online platform showed limitations in performing direct communication and language acts. These challenges influenced the students’ motivation to maintain their positive attitude during a classroom activity. The current studies attempts to determine the students’ identification of motivating teaching practices or strategies in ESP classes, especially in a vocational education setting.

Theoretical Framework

Motivation in language learning

Motivation is a personal attribute that supports students to possess the quality of perseverance and persistence in mastering the target language (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2007; Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). Even though many conditions and elements are needed to accomplish successful foreign/second language (L2) learning, most teaching practitioners consider that motivation is a major stimulus that supports language learning achievement (Lai, 2013; Ruesch et al., 2012). It has been said to drive the process of language learning (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2007). Even the brightest students struggles in learning the target language without adequate motivation (Dörnyei, 2001). On the other hand, highly motivated students can master the target language more easily regardless of their cognitive characteristics, language ability, or learning conditions (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2007; Ruesch et al., 2012). Therefore, motivation plays a major role in the students’ language attainment.

Students’ attitude and their motivational state in learning L2 are strongly correlated. Students’ anxiety levels influence their performance in mastering the L2 knowledge (Liu & Huang, 2011) and their attitude about L2 learning is highly influenced by their perception of their ideal L2 self (Lee & Lo, 2017; J. Lee & Yi, 2017). The ideal L2 self refers to the use of students’ skills to avoid negative results in L2 learning (Shoaib & Dörnyei, 2005). Thus, students’ intrinsic motivation, including the individual’s objective in learning a target language and their determination to master it, has positive relations to their achievement (Carreira et al., 2013). On the other hand, external factors, such as students’ relationships and interactions with their peers, reflect their motivational level. High-motivated students are usually associate with others who have high motivation while low-motivated students tend to interact with unmotivated students (Chang et al., 2016).

Intrinsic motivation is considered to be the major element in the L2 process. Students’ ideal-self as a competent language user influences their learning motivation (Nakamura, 2019). Personality traits and motivation are viewed as predictors in the L2 attainment (Cao & Meng, 2020). Students’ who are confident in their language abilities are more engaged in classroom activities (Griskell et al., 2020; Leona et al., 2021). Self-determination is a major driving force in language learning (Oga-Baldwin & Fryer, 2020a). Self-assessment is also crucial, as it supports the students’ aspirations in L2 learning (Birjandi & Tamjid, 2010). Furthermore, students’ motivational profiles align with their experience in L2 learning. Thus, students’ perseverance and persistence in L2 learning are supported by their positive concepts and aspiration.

Motivational teaching strategies

Students’ success in language learning is highly correlated with the teachers’ skills and teaching methods (Maeng & Lee, 2015). Teachers’ abilities is an important factor in integrating motivational strategies in the teaching and learning process (Bernaus et al., 2008). Motivational strategies refer to implementing instructional mediation to encourage students’ motivation (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). In implementing the motivational strategies, teachers need to consider several basic conditions; “(a) appropriate teacher behaviors and a good relationship with the students; (b) a pleasant and supportive classroom atmosphere; and (c) a cohesive learner group with appropriate group norms” (Dörnyei, 2001, p. 31). When better teachers’ strategies are employed, students can better achieve language knowledge. Thus, understanding different kinds of students’ learning motivation is crucial in achieving the success of language learning (Lee & Yi, 2017).

The learning environment significantly contributes students’ motivated behavior. An environment that offers an opportunity to establish a good group of learners impacts positively on improving motivation in L2 classrooms (Chang, 2010). A learning environment that provides more cooperative activities instead of competitive activities enhances students’ motivation (Hu & McGeown, 2020). Students’ motivational growth results from a constant collaboration between their perception of environmental contexts and their ideal L2 selves (Du & Jackson, 2018). Students’ perceived autonomy is also significant in cultivating their enjoyment in L2 learning, increasing their motivated attitude (Tanaka, 2017). An improper learning environment, such as the limited teaching utilities and equipment, is considered a demotivating factor (Alavinia & Sehat, 2012). Thus, the availability of learning resources contribute positively to the students’ attitude (Zheng, 2012).

Furthermore, students’ motivational states are highly related to teachers’ teaching methods, styles, and behavior. Teachers’ understanding of students’ individual goals in L2 learning is crucial as students’ motivation can be cultivated by supporting their knowledge of proficiency and affinity (McEown et al., 2014). Students’ intrinsic motivation can be improved by teachers’ support for autonomy (Carreira et al., 2013). Creative pedagogy that establishes a pleasant atmosphere also increases the students’ motivation (Liao et al., 2018). Game-based learning, for instance, is one of the creative techniques that improves students’ engagement in L2 learning and increases their academic motivation (Partovi & Razavi, 2019). A student-centered approach has also been seen to provide more motivating conditions than a teacher-centered approach (Kulakow & Raufelder, 2020) stimulating students’ self-determined motivation in the learning process. Thus, the student with a stronger belief in achieving certain knowledge reflects higher motivation (Baker & Anderman, 2020). Teachers’ ability to handle the class size and provide extracurricular activities also positively influences students’ motivation, as they cultivate a good relationship between teachers and students (Daif-Allah & Alsamani, 2014). Therefore, motivating teaching strategies in language learning can improve students’ motivation.

Previous Studies

Several studies have mentioned the significance of motivational teaching strategies in increasing students’ success while learning a L2 (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008; Kumazawa, 2013; Maeng & Lee, 2015; Moskovsky et al., 2013; Song & Kim, 2016). Dörnyei and Csizér (1998) proposed the notion of motivational teaching strategies in their studies which investigated “ten commandments for motivating language learners”. The study compiled a series of macro and micro strategies to help students improve their motivational levels. It was also suggested that teachers’ motivational teaching practices highly influenced students’ motivation. Guilloteaux and Dörnyei (2008) conducted research using a questionnaire to investigate the effects of specific strategies on students’ motivation. They included South Korean 27 teachers and 1300 students in in the study. They measured students’ motivation using a self-reported questionnaire and classroom observation. The results showed that teachers’ motivational strategies contributed significantly to the students’ motivation. Similarly, Maeng and Lee (2015) conducted similar research by investigating the role of teachers’ motivational strategies in learning and teaching. They studied the teaching behavior of 12 English teachers in Korea by analyzing videotapes of the teachers’ classes. The results revealed that motivational strategies had a positive correlation on the students’ language proficiency.

Furthermore, Moskovsky, et. al. (2016) investigated the effects of teachers’ motivational strategies on learners’ motivation in Saudi Arabia. They conducted a quasi-experimental design involving 14 EFL teachers and 296 students. The results suggested that teachers’ motivational state improved students’ motivation in EFL learning. Song and Kim (2013) explored two South Korean teachers’ experiences in EFL learning using an in-depth qualitative inquiry. They interviewed two female teachers on their motivation levels during the teaching process. The study revealed that students’ motivation had changed over time, following the teachers’ motivation. Similarly, Kumazawa (2002) conducted research involving young teachers in a Japanese secondary school. She investigated the influence of teaching motivation on the students’ motivational state. The findings suggested that teachers’ motivation can have an essential role in shaping students’ positive motivation on language learning.

A number of studies have investigated the influence of motivation in vocational education setting (Chukwuedo et al, 2021; Habibov et al., 2021; Keijzer et al., 2021; Liu, 2020; Nye et al. 2021; Zacher & Groidevaux, 2021). Habibov et al. (2021)_tested the hypothesis of the association of motivation with the satisfaction of public education. Utilizing a diverse sample of 27 post-communist countries in Eastern and Central Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus, they reported that students’ accomplishment was highly influenced by their intrinsic motivation. Keijzer et al. (2021) conducted a cross-sectional study to see if differences in individual characteristics of at-risk pupils influenced the association between perseverance and professional identity. The students who demonstrated greater persistence in their studies exhibited higher levels of achievement in vocational education, in contrast to their less persistent counterparts. Personal qualities, on the other hand, varied depending on human attributes. Finally, Zacher & Froidevaux (2021) reviewed several journal articles related to vocational behavior and development. One of their findings indicated that work motivation and behavior were crucial in a vocational setting.

In the teaching and learning process, Chukwuedo et al. (2021) employed a quasi-experimental study on self-directed learning intervention. The data were gathered from postgraduate vocational and adult education (n= 243). The result showed that educational intervention (e.g., vigor, devotion, motivation, and perseverance) improved students’ self-direction in learning process. Nye et al., (2021) suggested that motivation and satisfaction were strongly related to vocational interest. They conducted a seven-week longitudinal study involving 372 college students and a prediction of their academic achievement. These findings showed that vocational interest fit could be beneficial in identifying students who were likely to succeed in school and suggested several of the factors that underpinned this association. Finally, Liu (2020) compared the impact of extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy on Taiwan’s high school and vocational students. The results revealed that the improvement of future EFL learning was influenced by different motivational or social techniques based on the students’ characteristics of pre-college experiences.

Based on the previous studies, it seems evident that motivational teaching strategies could be vital in L2 learning. To improve students’ motivation, it seems that emphasis should be not only on the motivating teaching factors, but also on the demotivating ones. Thus, it is crucial to identify the teaching strategies that are not motivating. Understanding the students’ perception of demotivating teaching strategies helps teachers eliminate the strategies that influence students’ negative behavior toward L2 learning. Unlike the previous studies that focused on general L2, the present studies focuses on the motivational strategies that the students perceive as not motivating in an ESP setting, specifically in a vocational education setting. The previous studies also only investigated teaching strategies within the traditional setting. Their influence in an online classroom setting was not explored. In some vocational settings, the study focused only on how motivation influenced the learning outcomes. The influence of motivational strategies on the teaching process was not explored. As a result, the current study was planned to investigate the students’ perception of the teaching strategies that they consider not motivating in ESP online classes.

Statement of the problem

The current study investigated the students’ perception of the motivational teaching strategies in ESP online learning classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. An ESP class specifies the use of English as a medium of communication in a specific and certain field of study or profession (Basturkmen, 2010). Unlike the general EFL class, the ESP class uses more diverse language registers such as English for medicine, English for banking management, or English for accounting. It is designed to support the learners in mastering language efficiency in a specific environment. Thus, a specific syllabus and teaching methods are needed. Furthermore, this study is conducted in a vocational education setting where the main objective is to implement the skills in the real world. The vocational learning method focuses on the practices over the theory. One of the main drawbacks of ESP class is the limited time provided in the classrooms. Since most ESP students are not English majors, their initial language ability is very diverse. This condition creates more challenges. Furthermore, with the application of online learning classes, the exposure of language interaction and practices is more restricted. Hence, teachers need to understand the students’ condition and maintain their positive attitude during the teaching and learning process. By recognizing the demotivating strategies, the teachers can eliminate teaching practices that reduce their interest in language learning.

Theoretically, an investigation of the students’ perceptions of the demotivating teaching practices supports the teachers’ knowledge of determining appropriate techniques, methods, syllabus, and curricula in teaching ESP classes. Practically, by relating the students’ perceptions of the demotivating teaching strategies, teachers can project appropriate strategies to motivate ESP students. Thus, the present study sought to answer this question: What were the students’ perception of motivational teaching strategies in ESP online learning classes during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methodology

Participants

The participants were ESP students of the Faculty of Vocational Studies in an Indonesian public university. They were chosen based on convenience sampling. All students who take English for Specific Purposes classes in four study programs (physiotherapy, radiology, taxes, and library science) were invited to participate. They attended online classes for the first level of the ESP course. The class was conducted through Zoom and WhatsApp applications. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study and told that they should complete the questionnaire only when they agreed to participate. The questionnaire was administered online and in anonymity. Thus, the submission was considered as participants’ consent.

A total of 165 students from four study programs (i.e., physiotherapy [n=45], radiology [n=50], taxes [n=40], and library science [n=30]) responded to the questionnaire. There were 117 female and 48 male students ranging in age from 17 to 22 years old. The students had been studying English since junior high school/middle school. Thus, prior to their enrolment at the university, they had had six years of English learning experience in formal education and their English proficiency was between beginner and intermediate levels.

Research instrument

The instrument used in the current study was adapted from Dörnyei and Csizér's (1998) motivational teaching strategies. This questionnaire has been widely administered in motivational teaching practices research; thus, its validity and reliability have been confirmed (Dörnyei & Csizér, 1998; Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). Considering the Indonesian students’ English proficiency, the questionnaire was translated into Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia) to facilitate the participants’ response. Two experts were invited to evaluate the translated questionnaire, and 30 students were invited to participate in a pilot study.

The original questionnaire consisted of 51 micro-strategies. The micro-strategies were grouped into several macro-strategies. Macro-strategies covered larger classifications of related micro-strategies (teaching practices). Motivational teaching practices that did not apply to the ESP class in an online college-level classroom were eliminated (macro-strategies ‘rule’ and ‘decoration’). Thus, the questionnaire presented a list of 46 teaching practices. It used a five-point Likert Scale to measure the students’ perception with 1 being “not motivating” and 5 being “most motivating.” A Bivariate Pearson test was conducted to measure the validity and reliability of the translated questionnaire.

Procedure

The questionnaire was created in Google Forms. Responding to the questionnaire, the students were guided to recall their previous English-learning experiences. They were informed that the questionnaire was for research purposes, and it did not affect their grades. Their participation was voluntary. Considering the internet connection and data reception, the students were given one week to complete the questionnaire.

The collected data were analysed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 21 (IBM corporation) to determine its mean score and standard deviation. Since the questionnaire explored the students’ perception of the teaching practices, the aim of analysing the data was to find their perception of the teaching practices that were not motivating or demotivating in an online ESP learning context. Thus, the teaching practices were ranked in order in terms of the mean score from the lowest to the highest. The analysis revealed the teaching practices that were considered demotivating.

Results

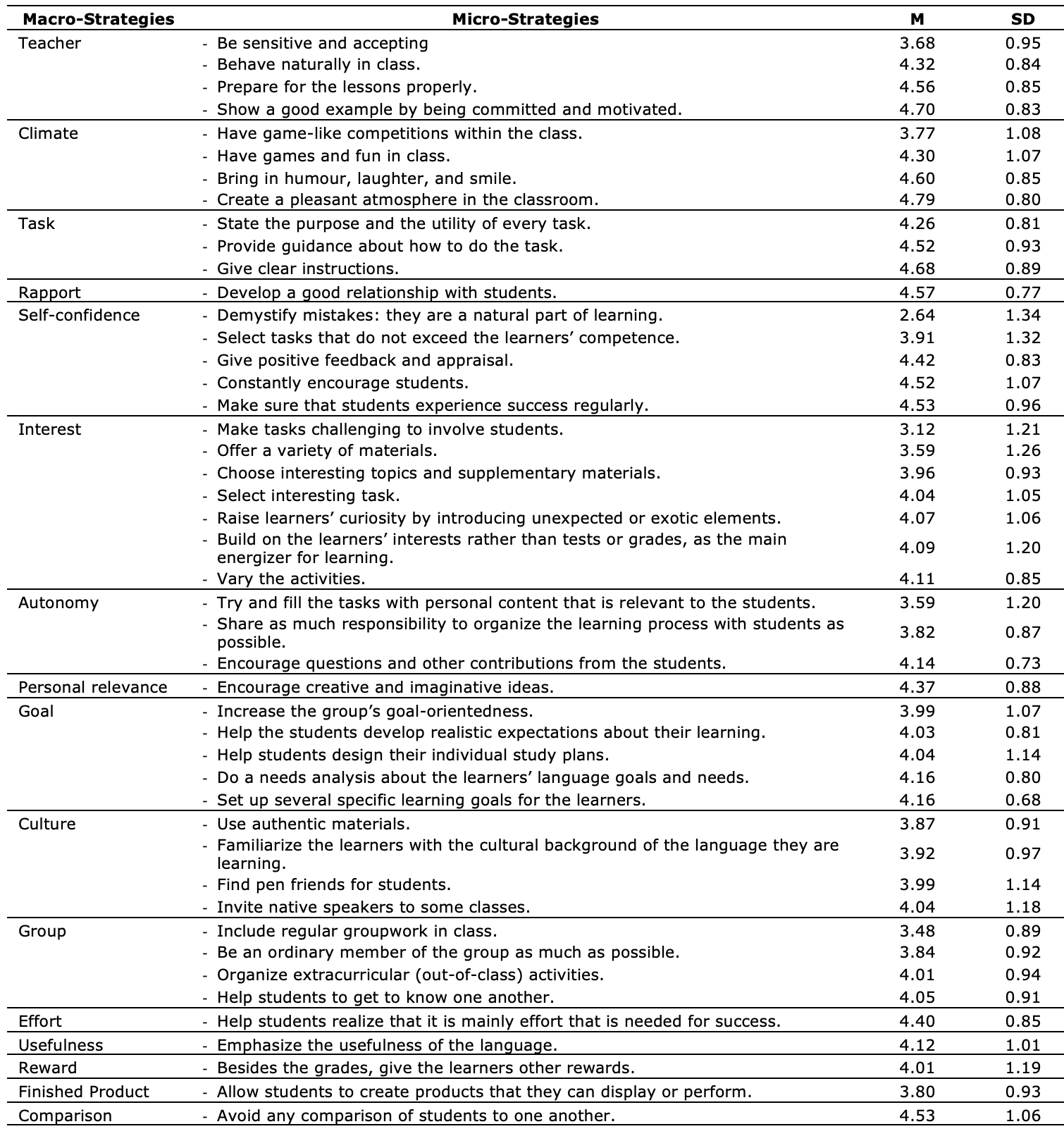

This section examines the mean scores and standard deviations from the collected data. The data were processed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 (IBM corporation). To figure out the students’ perception of the most and least motivating strategies, the results from the mean scores of micro-strategies were ranked ordered from the lowest to the highest in each macro-strategy. For the macro-strategy “teacher,” for instance (see Table 1), the highest score is “show a good example by being committed and motivated” while the lowest one is “be sensitive and accepting.”

Table 1. The micro-strategies rank in order from the lowest to the highest rank.

Acknowledging macro-strategies is crucial, as it illustrates the general framework of motivating teaching practices (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). For instance, in the macro-strategy domain of teachers, the most motivating teaching practice was giving a good example by being self-motivated. This result differs from Dörnyei and Csizér’s (1998) study which revealed that preparing proper lessons was the most motivating. Meanwhile, being sensitive and accepting was the least motivating, a similar result to Dörnyei & Csizér’s study. For the domain of interest, the most motivating strategy was using a variety of teaching activities, while the least motivating was the use of challenging tasks in the classroom. These results are also different from previous studies conducted by Dörnyei and Csizér, which suggested that selecting an interesting task was the most motivating teaching strategy in the domain of interest. However, the current findings are similar to Maeng and Lee’s (2015) study which showed that students’ motivation was influenced by interesting teaching methods.

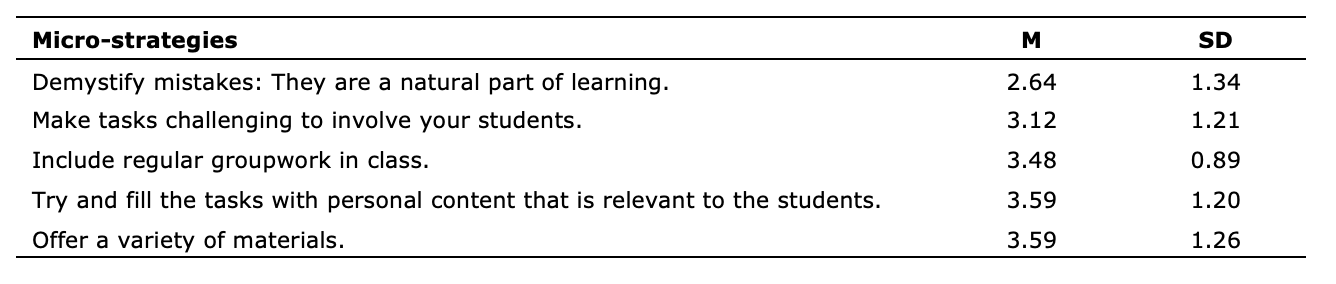

To determine the least motivating strategies, all the micro-strategies were ranked and ordered based on the mean scores, regardless of the macro-strategies. Table 2 shows the five lowest teaching strategies, reflecting the strategies that students found least motivating.

Table 2. The lowest rank of micro-strategies

There were no exact reasons why strategies were considered motivating or not motivating, as those factors changed according to the specific context and background (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2007). However, demotivating factors included several negative influences that eliminated the current motivation or external forces reducing their motivating behavior, intention, and ongoing action (Dörnyei, 2001). In an academic setting, recognizing the significant association between students’ motivation and academic performance in the teaching process is needed. Therefore, in the current study, the five lowest-ranked micro-strategies were considered demotivating factors for students. These results were quite different from Maeng & Lee’s (2015) study, which emphasized that teachers’ lack of experience in teaching methods resulted in students’ negative behavior. However, they are similar to Song and Kim (2016) study, which mentioned that challenging activities influenced teachers’ and students’ motivation over time.

Discussion

In exploring the students’ perception, there are three main components in the general framework of motivating practices: teacher-specific, course-specific, and group-specific motivational components (Dörnyei & Csizér, 1988). The macro-strategy “teacher,” for instance, is a teacher-specific motivational component. It is shown that among the four micro-strategies, students perceived the teaching practice “be sensitive and accepting” as the least motivational strategy and “show a good example by being committed and motivated” as the most motivational strategy. Based on the mean scores, the students felt motivated when they saw their teacher was motivated. The showed teachers to be their role models and their main motivational source in the teaching and learning process. If teachers were dedicated to a subject matter, students felt encouraged to follow their instruction (Escobar Fandiño et al., 2019; Hosseini & Shokrpour, 2019). When teachers showed enthusiasm and positive behavior during the teacher process, the students were exposed that positive attitude as well.

Meanwhile, teachers’ sensitivity in the classroom was not motivating for the students. In this Indonesian ESP context, students were accustomed to teacher-centered learning where they were conditioned to pay attention directly to the teacher. This created the students’ dependency on their teachers. They assumed that following the teachers’ order in academically related activities would guarantee success. As students’ academic achievement is mainly indicated by GPA, students tend to focus on the elements that help them increase their score which reflects their performance (Zeynali et al., 2019). Factors that did not directly influence their performance were overlooked. Thus, they perceived that teachers’ appearance of being sensitive in the classroom was not considered as the main factor in their behavior.

In the course-specific component “Task,”, giving explicit instruction is considered the most motivating, and stating the aim of the task is the least motivating. In an academic setting, students’ motivated behavior is encouraged when they engage in learning tasks and reaching their academic objectives effectively (Rotgans & Schmidt, 2011). However, it is important to understand that there is a possibility that all the micro-strategies are perceived to be motivating. As shown in the table, for the macro-strategy “task,” the average mean scores were above 4, which indicated that all the teaching practices were considered motivating. In the previous result, only three micro-strategies have high mean scores. Thus, it is important to look at the specific micro-strategies to investigate the motivating and demotivating strategies.

For the group-specific motivational components, the results implied that students’ positive relationship is considered to be the most motivating teaching strategy. When the students know each other well, they can cooperate and help each other without hindrance. In other words, students’ motivation is influenced by peer relationships. On the other hand, regular group work is perceived to be demotivating or the least motivating. Since the ESP setting requires students to perform their abilities immediately, students feel intimidated if they perform their skills in front of their peers. This anxiety causes the students to be more comfortable to have interaction directly with teachers instead of their peers. Moreover, in an online setting, group work mostly is conducted using Zoom meeting or chat-group. This activity is considered to be a hassle by students since they often have problems related to the internet connection. The lack of face-to-face interaction also could result in misunderstandings that start conflicts. Thus, this activity is considered to be the least motivating one. This finding is in line with the previous study, which mentioned that to ensure students’ competence, individual characteristics, and ideal L2 self should be recognized (Lee et al., 2017). Before determining how and when to use specific approach, students’ personalities should be assessed to determine whether they like to work collaboratively or individually (Csizér, 2020).

Furthermore, it is important to investigate the least motivating teaching strategies to maintain students’ positive behavior. By finding these strategies, the teachers can employ more effective methods in online classes. Based on the analysis, these are five demotivating teaching strategies.

The first strategy is “Demystify mistakes: They are a natural part of learning.” One of the main concerns in online learning is switching the methods and delivery while maintaining the learning objectives. These rapid changes confused the students as they were not ready to be exposed to different learning settings while the objectives of the study remained the same. Thus, they tried to focus on maintaining their grade, assuming it would help them reach their target. Since in the Indonesian learning setting, students were exposed to teacher-centred learning and score-goal oriented to pass a subject, students tried hard to avoid any mistakes during the learning process. In an online setting where the interaction between students and teachers was limited, students needed to find a way to self-evaluate their work. They tried hard to avoid any mistakes. Even though the teachers said it was okay to make mistakes, they still felt anxious about it. That was the main reason why the Indonesian ESP students considered that saying the mistakes were fine did not increase their motivation. Instead, students tended to be quiet and not participating in the classroom activities as they are afraid of making mistakes.

It is important to recognize the aspects that cause the students to lose self-confidence (Carreira et al., 2013). Since teachers’ attitudes can be external factors in motivating students, regulating the contextual situation in specific classrooms is needed. In an online setting, for instance, teachers need to understand that students’ main goal is to keep their pace in receiving the material while adopting the new method. Thus, students’ demotivating experiences of making mistakes established thoughts that mistakes should be avoided. Before employing specific methods or strategies, it is important to understand several kinds of learning motivation since students’ motivating factors are varied (Lee & Yi, 2017). In this setting, students were expected to pass certain grades to move on to the next level; thus, they possessed a goal-orientedness factor. Students’ goal-orientedness consists of individual goals, institutional constraint, and success criteria (Dörnyei, 2001). Students with individual goals perceive that avoiding mistakes is the way to achieve their goals. Therefore, teachers need to be aware of these goals to avoid demotivating practices (Falout et al., 2009). In short, students did not perceive this strategy as motivating.

The second strategy is “Make tasks challenging to involve your students.” Since teachers are mostly not familiar with the online setting, they tend to use the online platform as a tool to provide students tasks or assignments. Online learning requires teachers to provide delivery, interaction, and assignment. However, because of the time constraints, internet connections, and the availability of devices, teachers tended to focus on only giving the assignments. They uploaded material, expected students to read them independently, then asked students to submit the related assignment. The major change in this teaching process shocked the students as, in the Indonesian setting, students were used to teacher-centred learning. Students who were mostly listening to teachers’ explanations were forced to finish the task independently without proper explanation. The condition created a view that online learning was full of assignments. This phenomenon established the students’ thought that doing overwhelming online assignments was stressful. Parker et al. (2021) mentioned that students’ achievement was highly influenced by their enjoyment. Overwhelming assignments caused boredom, which resulted in low motivation. Experienced teachers tend to focus more on the discussion than evaluation activity (Maeng & Lee, 2015). Thus, challenging tasks or assignments were demotivating factors for them.

One of the most important factors in increasing and maintaining the students’ positive behavior is creating an enjoyable classroom (Carreira et al., 2013; Ruesch et al., 2012). In an online setting, students were already stressed with the possibility of a blackout, slow internet data connection, and problems with their equipment. Providing challenging tasks was an additional burden for them. Although for high-level students completing the tasks is an enjoyable activity, challenging assignments lead to anxiety for lower-lever students (Carreira, 2011). Students are at risk of being demotivated when facing cognitively demanding materials (Falout et al., 2009). Since the majority of ESP students were not English majors, they had the time constraint and exposure of using English in daily activities. Thus, their English skill was in a higher level. This is the main reason they considered that getting challenging tasks obstructed their enjoyment in learning and demotivated them.

Students’ next practice perceived as demotivating in online ESP class is ‘include regular group work in class.’ In a traditional setting, students enjoyed group work as they could assist each other in completing the task. However, the online setting offered a different challenge. Since they could not meet physically, they tended to use online platforms, such as video call group meetings or chat group meetings. Those two platforms were not as effective as a traditional group work setting. Students felt it troublesome conducting small group assignments within the classroom. In Zoommeetings, for instance, students would be separated into rooms. This process took time and some students ignoring the instruction could not follow the pace of learning. Those technical processes frustrated the students and diverted their focus and attention from learning the materials. This experience created a burnout in studying, which resulted in students’ low performance (Barratt & Duran, 2021). Instead of focusing on understanding the materials and completing the tasks, students spent their time making sure the online group platform worked properly. Some device problems, such as slow connection speed, audio that was not clear, or a member’s sudden loss of connection were some of the bad experiences that students faced in online group work (Maqableh & Alia, 2021). These caused anxiety and decreased students’ self-efficacy in learning (Mauludin, 2020). It reduced their positive motivation.

Demotivating environments, as well as demotivating peers, tend to have a negative influence on students’ motivation (Mauludin et al., 2021; Tanaka, 2017;). In mastering a foreign language, peers’ influences become a significant factor. If the students feel enjoyment and are comfortable with their peers, their positive, motivated behavior increases. On the other hand, if their interaction with their peers is uncomfortable, their negative behavior grows. Even in a traditional setting, disagreement among the group members causes demotivated state (Chang, 2010). In an online setting, when many factors influence the success of the group work, disagreements and an uncomfortable setting can lead to frustration. Controlling peers' behavior is also a significant factor in maintaining a positive ambiance in online group work. It is difficult to check progress regularly or share their difficulties in completing the task since they cannot meet each other. Thus, teachers need to understand the settings that cause the students’ anxiety and the conditions of their peers. Grouping students with similar characteristics and interests can be a solution to maintain their positive behavior regardless of the online technical problems. Creating a positive climate to improve their motivation is the priority. Therefore, doing group work in ESP online classes can be demotivating for the students.

The teaching practice “Try and fill the tasks with personal content relevant to the students” was also considered demotivating. The main aspect of ESP learning is related to the specific registers and linguistic knowledge related to their profession. Thus, their goal is to master English language as applicable in their related profession. Different from general EFL learning, which covers a wide range of topics and contents, ESP contents are very limited and specific. In this study students were familiar with the specific terms in their profession, as they had learned them from the specific subject course. For instance, students who majored in physiotherapy were already familiar with several English terms for giving treatment. Their challenge was to create a good construction of English expressions to deliver their thoughts. They needed to learn to converse and interact with their patient in English. Thus, their goal was to learn the language that they need. The challenge was that the ESP teachers were mostly not physiotherapists. The personal content that they thought was relevant might not be relevant for the students. In terms of subject knowledge, the students knew the field of physiotherapy better. Therefore, providing tasks with personal content was not considered a motivating factor for them.

Learning output relies on the learning input and students’ subjective enthusiasm in long-term learning (Zheng, 2012). Hence, it is essential for them to find their personal goal in learning a language. Students tend to feel demotivated when they learn something that has no significance in their life (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). As mentioned before, since our ESP students were not in an English major, they did not possess an initial intrinsic motivation to learn English for their enjoyment. Enjoyment-seeking language-based activities are highly motivating for English majors, but for non-English majors (Falout et al., 2009; Mauludin, 2021). Most ESP students in Indonesia learned general English in their junior and senior high school. Their knowledge was limited to the grammatical forms and vocabulary, which they rarely used since English is not widely spoken in the country. When they learned ESP, they were forced to apply the language in the situational context which often led to surprising situations. They were unfamiliar with implementing specific expressions and vocabulary in the real world. Thus, they perceived that personal content did not significantly improve their skills.

The final teaching strategy that was considered to be demotivating in this study was “offer a variety of materials.” As previously mentioned, online learning was overwhelming for the students, as they are forced to learn independently most of the time. The interaction with their teachers was limited and not as flexible as the traditional setting. In their experience, online learning only provided a lot of materials and assignments. In a traditional setting, the students relied on their teachers to deliver the material, taking notes, and asking questions to clarify. However, in an online setting, the students’ independence was challenged (Lin et al., 2017). To understand the material better, they needed to concentrate more and could no longer rely on the teachers’ explanations. Furthermore, online materials tend to be not friendly with the variety of students’ technological devices and their ability to use them (Maqableh & Alia, 2021). For instance, one of the students’ devices might not work to access certain materials or students who have old computers or out-to-date software might not be able to access several sources. Overloading materials also affected their engagement and created burnout (Barratt & Duran, 2021). Therefore, they showed negative behavior once the teachers required a variety of materials.

It should be noted that students tend to show demotivated behavior if they have low proficiency in English (Falout et al., 2009). Since English is not their native language, the materials in English are very challenging for them. In a traditional setting, teachers delivered the material using the native language and assisted them in understanding the topic. In an online setting, although the teachers still participated in delivering the material, most of the time the students were expected to understand most of the materials on their own. Since the materials were in English, they could not comprehend them. Teachers should understand the students’ motivational state before requiring a wide variety of materials. Teachers might think that the various materials are beneficial for them; however, their perceptions of the materials might differ (Ayuningtyas et al., 2022;Bernaus et al., 2009; Oga-Baldwin & Fryer, 2020b). Thus, inappropriate materials may become a demotivating factor, as they are not favorable for the students.

Based on the discussion, it has been shown that some teaching practices were considered to be demotivating factors in online setting classes. ESP classes were initially challenging as most students were in the low-intermediate level of English. Even in a traditional setting, employing some motivating teaching strategies was challenging. In an online setting, teachers needed to understand more about students’ motivational states, as they adapted to a new learning environment. Emphasizing mistakes is a natural part of learning while providing a challenging task, creating regular group work that included personal content to the task, and offering a variety of materials were not considered motivating strategies in ESP online classes.

Conclusions

Since the study was conducted in an Indonesian ESP education setting with Indonesian students; the results should not be generalized to other contexts. Several important factors can be emphasized.

First, the findings show five teaching strategies that were perceived to be demotivating in online learning classes. Most of the strategies were related to the course-specific component, in which students found it demotivating if teachers provided strategies related to tasks or instructions. This reflects that in an online setting, teachers need to employ specific instruction that is more suitable in online classes. Providing challenging tasks, variable materials, or even taking part in group work was perceived to be demotivating. Hence, teachers should prioritize establishing a good atmosphere and enjoyable classroom before employing specific instructions related to topics or tasks.

Secondly, it is important to identify the different kinds of learning motivation before applying motivating teaching strategies in ESP online classes. Teachers may employ specific motivating teaching practices; however, students should have a similar perception to be effective. Teachers may think that specific teaching practices are motivating, but students may think differently. Therefore, students’ perceptions influence their motivation, but teachers’ perceptions do not. This means that in online classes assessing the students’ perception is crucial before implementing certain teaching strategies.

It also should be mentioned that no absolute and universal teaching strategies exist. Their application is rapidly changing and very diverse reflecting different contexts, students’ personalities, and classroom environments. Thus, understanding students’ individual needs should be the priority before employing the teaching strategies. More importantly, the findings show that students’ perception is important since teaching strategies will motivate them if considered motivating.

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, the data used in the current study is limited since it only includes a questionnaire. Further research should investigate more aspects, including the relationship between demotivation and their age, cultural background, and learning experience since students’ motivated behavior is influenced by many factors. Furthermore, the relationship between students’ demotivating behavior and their learning outcomes should also be explored. The study was conducted in an Indonesian ESP classroom with all Indonesian students. The results may vary based on the cultural settings. Further research in a heterogenous learning environment will provide better insights into demotivating factors in ESP classes.

References

Alavinia, P., & Sehat, R. (2012). A probe into the main demotivating factors among Iranian EFL learners. English Language Teaching,5(6), 9–35. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n6p9

Alqurashi, E. (2019). Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments. Distance Education, 40(1), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1553562

Ayuningtyas, P., Mauludin, L. A., & Prasetyo, G. (2022). Investigating the anxiety factors among English for specific purposes students in a vocational education setting. Language Related Research, 13(3), 31-54. https://doi.org/10.52547/LRR.13.3.3

Baker, A. R., & Anderman, L. H. (2020). Are epistemic beliefs and motivation associated with belief revision among postsecondary service-learning participants? Learning and Individual Differences, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101843

Barratt, J. M., & Duran, F. (2021). Does psychological capital and social support impact engagement and burnout in online distance learning students? Internet and Higher Education, 51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2021.100821

Basturkmen, H. (2010). Developing courses in English for Specific Purposes. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bernaus, M., Wilson, A., & Gardner, R. C. (2008). Teacher motivation strategies, student perceptions, student motivation, and English achievement. The Modern Language Journal, 92(3), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00753.x

Bernaus, Mercè, Wilson, A., & Gardner, R. C. (2009). Teachers’ motivation, classroom strategy use, students’ motivation and second language. Porta Linguarum, 12, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.31869

Birjandi, P., & Tamjid, N. H. (2010). The role of self-assessment in promoting Iranian EFL learners’ motivation. English Language Teaching, 3(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v3n3p211

Cao, C., & Meng, Q. (2020). Exploring personality traits as predictors of English achievement and global competence among Chinese university students: English learning motivation as the moderator. Learning and Individual Differences, 77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101814

Carreira, J. M. (2011). Relationship between motivation for learning EFL and intrinsic motivation for learning in general among Japanese elementary school students. System, 39(1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.01.009

Carreira, J. M., Ozaki, K., & Maeda, T. (2013). Motivational model of English learning among elementary school students in Japan. System, 41(3), 706–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.07.017

Chang, C., Chang, C.-K., & Shih, J.-L. (2016). Motivational strategies in a mobile inquiry-based language learning setting. System, 59, 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.04.013

Chang, L. Y.-H. (2010). Group processes and EFL learners’ motivation : A study of group dynamics in EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 44(1), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2010.213780

Cheng, H. F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt048.0

Chukwuedo, S. O., Mbagwu, F. O., & Ogbuanya, T. C. (2021). Motivating academic engagement and lifelong learning among vocational and adult education students via self-direction in learning. Learning and Motivation, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2021.101729

Csizér, K. (2020). The L2 motivational self system. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.). The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language earning, (pp. 71–93). Palgrave Macmillan.

Daif-Allah, A. S., & Alsamani, A. S. (2014). Motivators for demotivators affecting English language acquisition of Saudi Preparatory Year Program students. English Language Teaching, 7(1), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n1p128

Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2020). Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes.Children and Youth Services Review, 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandment for motivating language students: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1191/136216898668159830

Du, X., & Jackson, J. (2018). From EFL to EMI : The evolving English learning motivation of Mainland Chinese students in a Hong Kong University. System, 76, 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.05.011

Escobar Fandiño, F. G., Muñoz, L. D., & Silva Velandia, A. J. (2019). Motivation and E-learning English as a foreign language: A qualitative study. Heliyon, 5(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02394

Falout, J., Elwood, J., & Hood, M. (2009). Demotivation: Affective states and learning outcomes. System, 37(3), 403–417.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.03.004

Griskell, H. L., Gámez, P. B., & Lesaux, N. K. (2020). Assessing middle school dual language learners’ and English-only students’ motivation to participate in classroom discussion. Learning and Individual Differences, 77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101799

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00207.x

Habibov, N., Auchynnikava, A., & Lyu, Y. (2021). Association between “grease-the-wheel”, “sand-the-wheel”, and “cultural norm” motivations for making informal payments with satisfaction in public primary, secondary, and vocational education in 27 nations. International Journal of Educational Development, 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102320

Hamidi, H., & Chavoshi, A. (2018). Analysis of the essential factors for the adoption of mobile learning in higher education: A case study of students of the University of Technology. Telematics and Informatics, 35(4), 1053–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.016

Hosseini, A., & Shokrpour, N. (2019). Exploring motivating factors among Iranian medical and nursing ESP language learners. Cogent Arts and Humanities, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1634324

Hu, X., & McGeown, S. (2020). Exploring the relationship between foreign language motivation and achievement among primary school students learning English in China. System, 89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102199

Keijzer, R., van der Rijst, R., van Schooten, E., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Individual differences among at-risk students changing the relationship between resilience and vocational identity. International Journal of Educational Research, 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101893

Kulakow, S., & Raufelder, D. (2020). Enjoyment benefits adolescents’ self-determined motivation in student-centered learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101635

Kumazawa, M. (2013). Gaps too large : Four novice EFL teachers’ self-concept and motivation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 33, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.005

Lai, H.-Y. T. (2013). The motivation of learners of English as a foreign language revisited. International Education Studies, 6(10), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n10p90

Lee, J. H., & Lo, Y. Y. (2017). An exploratory study on the relationships between attitudes toward classroom language choice, motivation, and proficiency of EFL learners. System, 67, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.04.017

Leona, N. L., van Koert, M. J. H., van der Molen, M. W., Rispens, J. E., Tijms, J., & Snellings, P. (2021). Explaining individual differences in young English language learners’ vocabulary knowledge: The role of extramural English exposure and motivation. System, 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102402

Liao, Y.-H., Chen, Y.-L., Chen, H.-C., & Chang, Y-L.. (2018). Infusing creative pedagogy into an English as a foreign language classroom: Learning performance, creativity, and motivation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 29, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.07.007

Lin, C.-H., Zhang, Y., & Zheng, B. (2017). The roles of learning strategies and motivation in online language learning: A structural equation modeling analysis. Computers and Education, 113, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.014

Liu, I-F. (2020). The impact of extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and social self-efficacy on English competition participation intentions of pre-college learners: Differences between high school and vocational students in Taiwan. Learning and Motivation, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101675

Liu, M., & Huang, W. (2011). An exploration of foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Education Research International, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/493167

Maeng, U., & Lee, S.-M. (2015). EFL teachers’ behavior of using motivational strategies: The case of teaching in the Korean context.Teaching and Teacher Education, 46, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.010

McEown, M. S., Noels, K. A., & Saumure, K. D. (2014). Students’ self-determined and integrative orientations and teachers’ motivational support in a Japanese as a foreign language context. System, 45, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.06.001

Maqableh, M., & Alia, M. (2021). Evaluation online learning of undergraduate students under lockdown amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: The online learning experience and students’ satisfaction. Children and Youth Services Review, 128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106160

Mauludin, L.A. (2020). Joint construction in genre-based writing for students with higher and lower motivation. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 38(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2020.1750965

Mauludin, L. A. (2021). Students’ perceptions of the most and the least motivating teaching strategies in ESP classes. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 9(1), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.30466/IJLTR.2021.120980

Mauludin, L. A., Ardianti, T. M., Prasetyo, G., Sefrina, L. R., & Astuti, A. P. (2021). Enhancing students’ genre writing skills in an English for specific purposes class: a dynamic assessment approach. MEXTESOL Journal, 45(3). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=23768

Moskovsky, C., Assulaimani, T., Racheva, S., & Harkins, J. (2016). The L2 motivational self system and L2 achievement: A study of Saudi EFL learners. The Modern Language Journal, 100(3), 641-654. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12340

Moskovsky, C., Alrabai, F., Paolini, S., & Ratcheva, S. (2013). The effects of teachers’ motivational strategies on learners’ motivation: A controlled investigation of second language acquisition. Language Learning, 63(1), 34–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00717.x

Nakamura, T. (2019). Understanding motivation for learning languages other than English: Life domains of L2 self. System, 82, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.03.006

Nye, C. D., Prasad, J., & Rounds, J. (2021). The effects of vocational interests on motivation, satisfaction, and academic performance: Test of a mediated model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103583

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., & Fryer, L. K. (2020a). Girls show better quality motivation to learn languages than boys: Latent profiles and their gender differences. Heliyon, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04054

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., & Fryer, L. K. (2020b). Profiles of language learning motivation: Are new and own languages different? Learning and Individual Differences, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101852

Panigrahi, R., Srivastava, P. R., & Sharma, D. (2018). Online learning: Adoption, continuance, and learning outcome--A review of literature. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.05.005

Parker, P. C., Perry, R. P., Hamm, J. M., Chipperfield, J. G., Pekrun, R., Dryden, R. P., Daniels, L. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2021). A motivation perspective on achievement appraisals, emotions, and performance in an online learning environment. International Journal of Educational Research, 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101772

Partovi, T., & Razavi, M. R. (2019). The effect of game-based learning on academic achievement motivation of elementary school students. Learning and Motivation, 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2019.101592

Rodrigues, H., Almeida, F., Figueiredo, V., & Lopes, S. L. (2019). Tracking e-learning through published papers: A systematic review. Computers and Education, 136, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.03.007

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). The intricate relationship between motivation and achievement: Examining the links between motivation, self-regulated learning, classroom behaviors, and academic achievement. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24(2), 197–208. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ996266.pdf

Ruesch, A., Bown, J., & Dewey, D. P. (2012). Student and teacher perceptions of motivational strategies in the foreign language classroom. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.562510

Shoaib, A., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Affect in life-long learning: Exploring L2 motivation as a dynamic process. In P. Benson & E. Nunan (Eds.), Learners’ Stories: Difference and Diversity in Language Learning, (pp. 22–41). Cambridge University Press.

Song, B., & Kim, T.-Y. (2016). Teacher (de)motivation from an Activity Theory perspective: Cases of two experienced EFL teachers in South Korea. System, 57, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.02.006

Tanaka, M. (2017). Examining EFL vocabulary learning motivation in a demotivating learning environment. System, 65, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.01.010

Wang, L.-Y.-K., Lew, S.-L., Lau, S.-H., & Leow, M.-C. (2019). Usability factors predicting continuance of intention to use cloud e-learning application. Heliyon, 5(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01788

Zacher, H., & Froidevaux, A. (2021). Life stage, lifespan, and life course perspectives on vocational behavior and development: A theoretical framework, review, and research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103476

Zeynali, S., Pishghadam, R., & Hosseini, Fatemi, A. (2019). Identifying the motivational and demotivational factors influencing students’ academic achievements in language education. Learning and Motivation, 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2019.101598

Zheng, Y. (2012). Exploring long-term productive vocabulary development in an EFL context: The role of motivation. System, 40(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.01.007