Introduction

According to O’Hara Devereau and Johansen, “Cross-cultural, cross-functional, and multilingual knowledge and fluency will be among the most highly valued assets in the emerging managerial landscape, whether one works in a global, regional, or national organization" (as cited in Zweifel, 2013, p. 1). In order to acquire these skills, foreign language classrooms can no longer focus primarily on vocabulary and grammar acquisition (the what and how of language use). Instead, the emphasis needs to shift to when it is appropriate to say certain things, why it is necessary to say those things, and a consideration of to whom one is speaking. Meaningful communication requires that all of these five elements-- what, how, why, where, and to whom—be used properly in order to avoid communication errors and misunderstandings. This clearly suggests that true language fluency cannot be accomplished without the knowledge of culture. There is an increasing recognition that learning a language is, in many respects, learning a culture (Byram, 1989; Guessabi, 2011; Kramsch, 1993; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013).

Numerous researchers have suggested that it is nearly impossible to teach language without also teaching culture (Brown, 2007; Kramsch, 1998; Kuang, 2007; Savignon & Sysoyev, 2005; Schulz, 2007; Tang, 1999). Knowledge of vocabulary and grammar rules is insufficient to reach higher levels of proficiency. This becomes more apparent if we think of proficiency as the ability to use language effectively in spontaneous and unrehearsed real-world situations with precision (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 2012; Nagel, 2018). Beyond vocabulary and grammar, cultural elements such as values, norms, beliefs, rituals, and traditions play a role in creating and understanding communications. Without knowledge of the cultural referents of the words and phrases of any language, higher levels of proficiency will remain outside the reach of learners (Kramsch, 1993; Peck, 1998; Seelye, 1982). Evidence continues to support the notion that achieving higher levels of communicative competence demands the teaching of culture in the foreign language classroom (Canale, 1983; Canale & Swain, 1980; Hammerly, 1982; Lim, 2018; Lim & Griffith, 2002, 2016; Omaggio, 2001; Savignon, 2002; Savignon & Sysoyev, 2002; Stern, 1983). Without including culture in the classroom in meaningful, explicit, and integrative ways, learners will be less likely to reach higher levels of proficiency.

The purpose of this paper is to provide teachers with a strategy for including culture in their classrooms without requiring them to be experts in the culture. This strategy allows students to be able to demonstrate the relations between their culture and that of the target language. Further, this method can be used in concert with the regular teaching practices and needs of the students with respect to vocabulary and grammar.

This approach has been shown to produce improvement in both the receptive (listening and reading) and productive (speaking) capacities of students in classes where the strategy was implemented. In a recent study at one of the premier foreign language schools in the United States (Lim, 2020), listening scores showed improvements as high as 21%; reading skills as high as 19%; and speaking fluency as much as 11%. This approach is a powerful one in terms of increasing fluency and language acquisition. What is particularly interesting about these findings is that the weekly intercultural activities involved reading materials in the student’s native language after which students wrote a short response to targeted questions in their native language. Yet, listening and speaking scores showed impressive improvements over students who were not exposed to such lessons. This is more support for the fact that the critical thinking component and familiarity with the target culture help students devise strategies for decoding and encoding communication in a foreign language (Lim, 2020).

Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) and Language Proficiency

Although language learning may not follow a linear process, one of the first steps in foreign language acquisition is learning vocabulary. This is often accomplished by memorizing long lists of word pairs—one in the native language and one in the target language. Not all words, however, have a corresponding word in the native language. In such cases, students turn to the dictionary to learn the definition of the words. However, words have more than denotative (or dictionary) meanings. Words also have connotative meanings which are not always the same as those in the dictionary. Understanding these connotative uses depends on a knowledge of culture for correct interpretation. With an understanding and knowledge of culture, students move beyond simple “classroom” knowledge to a more authentic language use.

Let’s consider an example. In the mid-1990s, a U.S. advertising agency launched the Got Milk campaign featuring celebrities and famous personalities with the iconic milk mustache. The phrase, “Got milk?” appeared below the person. In preparing this ad for Mexico, the board translated the expression as “¿Tienes leche?” Here is a clear example of where grammar and vocabulary fail us. If the translator had a deeper cultural knowledge of Mexico, they might have understood that this phrase is likely to have been translated as “Are you lactating?” Imagine the confusion of a Spanish speaker who sees a picture of the Russian president with a milk mustache with the expression “¿Tienes leche?” across the poster. It is grammatically correct, but lacking in cultural conventions (Rossen, 2018; Zweifel, 2013).

Similar examples abound where it is clear that campaign slogans can be unsuccessful based on a lack of cultural underpinnings in the use of language. When Mitsubishi marketed its Pajero in Mexico, the manufacturer changed its name to Montero. In some Spanish-speaking countries montero is a slang word for “masturbator.” In 2021, Mitsubishi stopped selling the Pajero/Montero due to poor sales (Frank, 2021).

A final example concerns a sign found in an Acapulco Hotel which proudly proclaimed that “The manager has personally passed all water served here.” Any native speaker of English would likely tell you that “pass water” is a common expression meaning “to urinate.” The sign doesn’t make one want to rush out for a glass of water “passed” by the hotel manager (Zweifel, 2013).

Amusing anecdotes aside, knowing the culture of a target language helps a learner to understand nuances and the intended meaning of communications. The cultural values of a society are mirrored in their use of language. It is very common for the meaning of an expression to be carried in elements such as the pitch, the intonation, or facial expressions rather than simply on the dictionary definition of the words. To help learners achieve higher proficiency levels and become effective communicators, and to facilitate interpretation over simple translation, teachers must teach culture (Mizne, 1997).

Cultural, Linguistic, and Intercultural Communicative Competence

Although related, cultural competence and intercultural communicative competence have a critical difference. When we talk about cultural competence, we are referring to specific cultural knowledge such as history, norms, values, and traditions of a society. On the other hand, intercultural communicative competence refers to all of these things PLUS the ability to use this knowledge in combination with linguistic, sociolinguistic, and discourse competencies so that the messages will be easily understood (Byram, 2009; Canale, 1983; Canale & Swain, 1980). It is this intercultural communicative competence that helps learners avoid the kinds of translation problems outlined earlier.

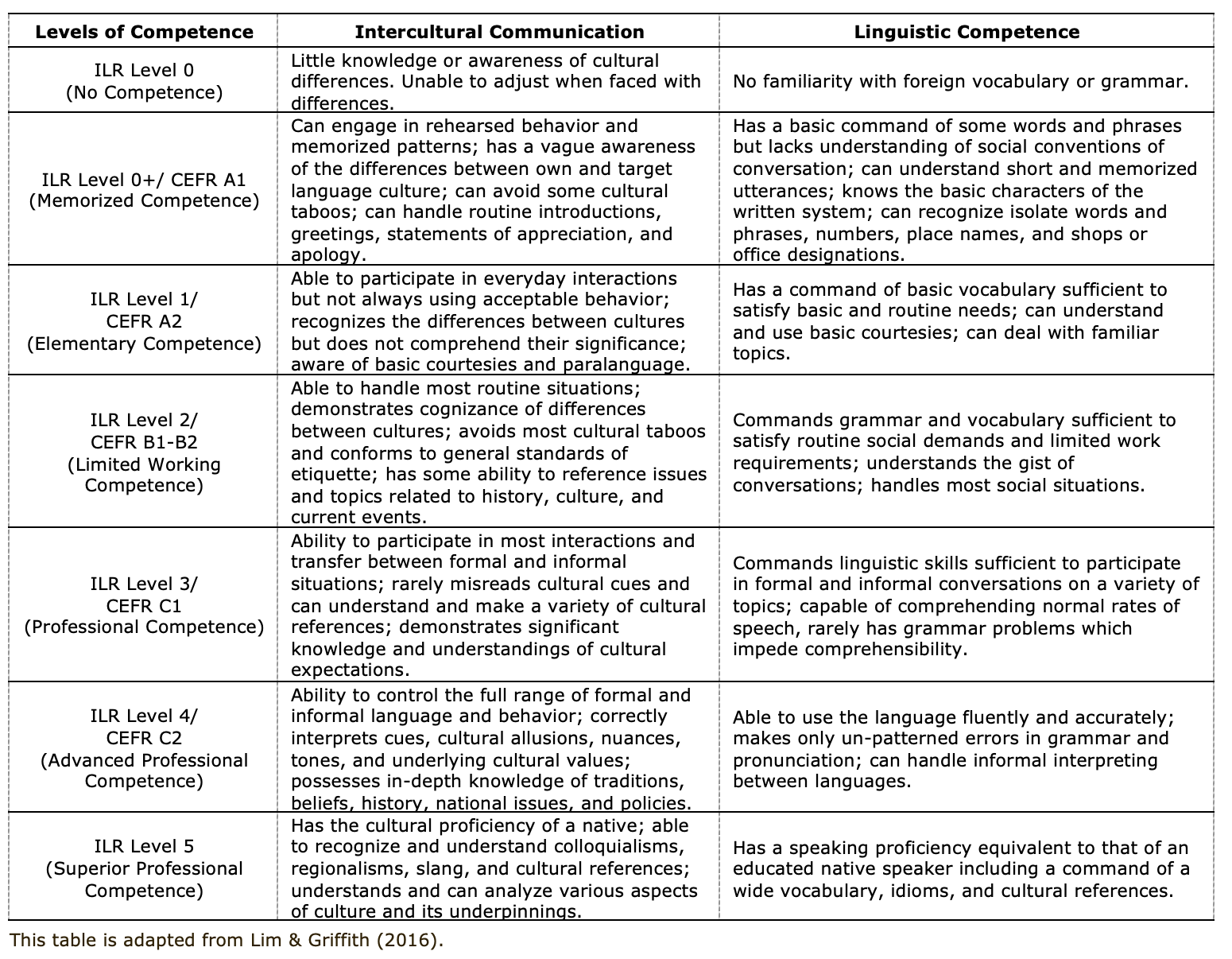

Like language acquisition, ICC can be viewed as progressing along a continuum. The Interagency Language Roundtable (2012) has created a set of categories ranging from 1-5 corresponding to its linguistic competency framework. Similarly, competence levels may also be related to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2020). Below is a table summarizing the levels.

Table 1. Skill levels summary for intercultural communication and linguistic competence

To summarize, the Table above shows a clear progression from lower to higher order thinking skills, as well as the kind of knowledge required at each level. Lower levels of proficiency (Level 2 and below), are more likely to require the use of lower order thinking skills (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; Bloom, 1956). According to Bloom’s revised taxonomy, these lower levels rely on skills such as recalling, recognizing, classifying, summarizing, and applying information. In other words, proficiency levels 0+ through 2 rely heavily on factual knowledge such as terms, descriptions, and details. Conceptual knowledge, including classifications, categories, and a general knowledge of principles, are also characteristic of lower levels of proficiency (Armstrong, 2015). This would include things like holiday celebrations, historical figures, food preferences, and favorite leisure activities.

The acquisition of higher levels of language proficiency and intercultural competency, on the other hand, relies on higher order thinking skills including analysis, evaluation, and creation. Such skills depend on procedural and metacognitive knowledge rather than more factual information typical of the lower proficiency levels (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; Armstrong, 2015; Bloom, 1956). For instance, this might include an assessment of how sports affect broader cultural values or how remote work is likely to change the nature of social relations in a society.

The implications of this approach for the classroom means that teachers can no longer only teach cultural facts for students to memorize. Such a strategy does not advance ICC much. Classroom activities must include tasks which require higher order thinking skills for their resolution. Additionally, activities should include an emphasis not only on learning culture but on metacognitive strategies to help students correctly perceive and interpret the target culture (Gonen & Saglam, 2012; Sieck, et al., 2013; Thanasoulas, 2001). Rather than being content to introduce cultural facts (e.g., Americans celebrate Thanksgiving in November), teachers must facilitate student exploration into cultural inquiry. They must help and guide students to an awareness, not only of the target culture, but of how the student’s own culture influences communication, perception, and so on. By so doing, teachers create learning situations that activate higher order thinking skills. Educators should always strive to raise students’ awareness of their own culture while instilling some sense of greater intellectual objectivity by understanding connections to their own culture and traditions (Deardorf, 2009; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009).

Classroom Implementation

In spite of the mounting evidence showing an important relationship between cultural knowledge and language proficiency, cultural studies continue to take a backseat in foreign language classrooms. Many reasons have been offered to explain this lack of attention to culture-based instruction (Byram & Kramsch, 2008; Gonen & Saglam, 2012; Omaggio, 2001). The first problem teachers are likely to face concerns an already full curriculum or one that is fully prescribed complete with lesson plans. For many teachers there is simply no time for them to divert their attention from the main curriculum to spend time on teaching culture. Many believe that it is inappropriate to expose students to these cultural teachings until basic vocabulary and grammar have been mastered. Teachers also believe that students will get relevant cultural exposure later in their studies but the sad reality is that for most students, this exposure never really takes place.

Another problem is that teachers are afraid they don’t have sufficient knowledge of the target culture, especially if they are not native speakers of the target language. This fear makes it more likely that teachers will rely mainly on teaching facts or culture capsules often found in the texts. A third problem concerns students’ negative attitudes. When people encounter unfamiliar situations, it is common for them to try to make sense of these situations by interpreting them through their own cultural knowledge and framework. Işik (2003) notes that this tendency to see things through our own cultural lens can pose problems for foreign language teaching. Since students are using their own framework to assess and evaluate the target culture, they may regard some incidents as negative and thereby reject the target culture values. These negative attitudes can make it more difficult to learn the target language (Amirian & Bazrafshan, 2016). The fourth problem is that teachers may not have received explicit training in how to teach culture. As a result, teachers may not have the skills necessary to frame cultural information and discussions for their students (Jennings, 2001).

The teaching of these ICC skills can take a myriad of forms limited only by the creativity and resources of the teacher. The activities need to focus on the needs of the students and, to be particularly successful, should correspond roughly to the linguistic level of competency. In other words, if a student is a beginner, then the cultural activities should also be at the beginner level of proficiency. The activities may focus on any of the skills (i.e., reading, speaking, listening, writing) and may be conducted in either the first or second language. In the beginning, the activities are likely to use the student’s first language. However, this is not a drawback if one keeps in mind the purpose of these intercultural activities. As the student progresses, the activities will be more second language dependent reflective of the student’s linguistic skills. The important thing to remember is that we are working on increasing intercultural awareness in concert with linguistic skills.

In this strategy, teachers are not the central expert on culture and their role is not to teach culture. Rather, they are guides who facilitate the learning process. Good activities really have no right or wrong answers, but instead, they are designed to promote thought and awareness. Therefore, the teacher does not grade the “correctness” of the student’s response to the task. Instead, they assess whether or not the student has met the conditions of the task (e.g., Did they write at least 250 words? Did they answer all elements of the task?). Therefore, the job of the teacher is to find relevant and appropriate materials and to design meaningful tasks that engage the student while promoting a deeper intercultural awareness.

In order to help students learn to use the target language fluently, effective classroom activities must be related to the real life concerns, needs, interests, and daily life of the students (Allen, 2004). This means that the activities should have a personal relationship to the student so that the student recognizes a connection to his/her own life. These connections to their own lives make it more likely that students will share information and be participative in the task. Students can discuss how the new information relates to their own lives and therefore, help them make connections with the target culture. Such analysis and evaluation make it more likely that students will discover their own underlying beliefs and the role their culture plays in daily life (Beach, 1998).

Characteristics of Effective Activities

The goal of effective activities is to generate higher levels of ICC. In order to accomplish this, activities must employ three features. First, the tasks should use the proper linguistic elements such as vocabulary, tense, structure. These should correspond with the level of the students’ proficiency and the material being studied in the classroom. Second, the activities must provide the opportunity for the student to become more aware of and learn about both his/her own culture and that of the target culture. Finally, truly effective activities need to employ critical thinking skills to complete the task.

More specifically, teachers should make sure that truly intercultural communicative competence activities should share a common set of characteristics. Successful activities should do all of the following:

- Make students aware of their own culture

- Provide knowledge of and information about the target culture

- Make students connect to L1 and L2 experiences

- Include higher order thinking skills

- Make the task relevant to their own lives

- Have no inherently correct answers or, at least, have multiple answers

Activities must include elements of the student’s native culture as well as that of the target culture. Simply asking a student to describe Christmas in the United States or design a holiday meal only looks at the target culture while completely ignoring the native culture. Students are often unaware of how much of their behavior is proscribed by their own culture, how their values are influenced by society and so on.

Understanding these concepts play a key role in understanding culture and its effects on all individuals can help to resolve and avoid cultural misunderstandings. For example, if Mexican students understood the naming conventions in the United States, they would understand why an American might refer to “Juan Octavio Sánchez Palomares” as “Juan Palomares.” If the student were listening for his name in a classroom or airport, he might be more likely to answer even though the name is clearly not right and at the very least should more correctly be noted as “Juan Sánchez.”

Embedded in this simple issue of a name, however, are much more fundamental cultural issues. For example, it tells us something about the importance of family and the order in which family names are presented. In the USA, for example, the maternal last name comes first followed by the paternal name. The name James Watson Clark signifies that the mother’s last name is Watson and the father’s Clark. If we were to shorten this name then it would be James Clark. This is exactly the opposite of the naming conventions in Mexico. More often, the maternal last name never appears in a person’s name in the USA. Again, this suggests something about families, family structure, and family relations. There is a lot of cultural information to unpack in the name of a person so it is important for teachers to create the opportunity for students to understand what names mean in the United States, for example, and how that relates to more basic cultural influences.

Examples: Theory into Practice

Now we can examine some examples of activities that meet the criteria outlined above. We will proceed up the competence scale beginning at ILR Level 1/CEFR A2. A typical activity in a foreign language classroom involves teaching about family and family relations. In this activity, after reading about a typical family in the United States, students draw their own family tree tracing three generations. Next, students create a family tree for a corresponding target language (TL) family. Students can also discuss together the roles and responsibilities of TL family members. [Skills included: remembering factual knowledge, understanding, and applying.]

At ILR Level 2/CEFR B1-B2, understanding the differences in family structures between native and target cultures is the focus. Students compare and contrast the typical household and family unit in the target country with their own. Students should consider such things as the typical family size, the kind of family unit, and the number of generations living in a single household. [Bloom skills: remembering factual knowledge, understanding, applying, and analyzing.]

At ILR Level 3/CEFR C1, Professional Competence, students can focus on understanding the differences in cultural values between native and target cultures. To achieve this, students compare and contrast specific aspects of cultures across the two countries (e.g., Mexico and the USA). To promote critical thinking, students might be asked to explore name changes when a woman marries. They might be asked, for example, to identify the underlying values of such changes and how that affects perceptions of males and females in a country. How would they feel if their country were to adopt the naming conventions of the United States when they married? What would that mean for their relations with others or identifying family members? [Bloom skills: remembering factual, conceptual and procedural knowledge, understanding, applying, analyzing, and evaluating.]

A careful review of these activities shows that they meet most of the conditions outlined earlier. Each of them requires the student to know something about his/her own culture (family structure); about the target culture (family structure, roles, size of families, etc.); making the task relevant to their own lives (outlining their own family tree) and connecting native and target cultures (comparing family sizes, types of families, etc.). Only the third activity outlined above includes the critical thinking component (analyzing and evaluating).

Now consider the following activities and determine whether or not they meet the criteria for a good activity. If they do not, how might they be improved? Students read an article about sports and society in the United States.[1] Students then write a 250-word essay on the following: “In what ways does the article suggest that sport has helped to shape social values in the United States. Describe three ways sports have contributed to nationalism.”

Although this is an interesting topic and asks the students for their opinions, it is missing four of the key elements for a good exercise. First, it does not require any knowledge of the student’s own culture. There is nothing in this activity that refers in any way to sports in Mexico. Second, it asks the students only to list, to recall, and to describe (all lower order thinking skills). In addition, there is nothing personalized about this assignment. Finally, there is clearly one correct answer to this question based on the article. So, while the students may well learn some cultural facts about the United States, they will not move the intercultural communicative competency bar much. Instead, this activity should include something like “This article states that sports help to define the morals and ethics of U.S. society. Please list three ways you believe that sports in Mexico help shape its values. Do you think sports play the same role in Mexico as in the United States? Why/why not?” Here we have resolved the problems in the original activity by asking the student to show some awareness of his/her own culture and by engaging higher order thinking skills (analysis and evaluation).

Here is another example. Students are asked to read an article on obesity in the United States.[2] Afterwards, students are asked to discuss the main reasons that Americans are obese and what they think the solution might be. Again, this is missing many of the key elements of a good activity. To make it better we need to ask students about their own cultural experiences with obesity so we might ask them whether or not the percentage of obese people has increased in Mexico as it has in the United States. We might solicit information on how they think obese Mexicans are treated compared with obese Americans. We might also see if there are any obesity problems in their own families and what they have done to try to combat this problem. Finally, we want to be sure to get some higher order thinking skills in so we might want to ask them create a diet plan for a family and analyze its nutritional content. Or, we could ask them to analyze the underlying cultural contexts (e.g., food preferences and habits) that are contributing to the epidemic and how those might be changed on a broader social context.

Teacher Roles and Responsibilities

In considering these activities, it is clear that the teacher does not have to “teach” the actual cultural materials. Instead, the teacher has to find good materials which the student then reads, watches, or listens to. These activities could even be done outside of the classroom helping to eliminate concerns with taking away time from the already demanding classroom schedule. But where should teachers get their information for the cultural awareness activities? First, it should be noted that resources can be in either the native or the target language. (Note that in the examples above, one of the articles was in English and one was in Spanish). Whether the teacher chooses to use the students’ native language or the target language depends on the students’ language ability. As the student’s linguistic capacities increase, the cultural materials are more likely to be in the target language. Second, the responses will likely be in the native language early on and can progress to increased usage of the target language. In order to keep the situation manageable, a good guideline is that the materials should be no more than three years old in order to make sure the information is current. In some cases, such as historical information, there may be some reasonable exceptions to the three-year rule. Try to vary the source of the materials to allow for a more rounded and interesting approach to culture. Use podcasts, YouTube, newspapers, and magazines. Just make sure that these are reputable sources.

When creating the actual tasks, avoid activities that require the students to study additional information. All the information they need should be contained in their own store of knowledge and in the materials you are having them watch, listen to, or read. In the example above about obesity, if you have not already studied foods or eating preferences in the United States, do not ask students to create a diet plan because they will have to find additional resources to complete the task. On the other hand, if you have studied foods and something about meals in the United States, then this is a good task.

The entire activity should take the average student no more than one hour to complete. This will not take away from normal teaching time, especially if the materials selected are reinforcing the vocabulary for the particular topic under consideration. Be sure to ask the student to activate knowledge about his/her own culture to solve the target language task. For example, ask students to talk about his/her own family Christmas traditions and what they mean. Then ask the student to compare those to the United States. Remember, true intercultural communicative competence, in addition to a knowledge of the target culture, means that the individual has an awareness of his/her own culture and how it influences behavior, values, and beliefs in his/her own culture. Understanding how those cultural factors operate in the real world is a necessary component to understanding and creating accurate communications.

Students enjoy talking about the work that they have done in these activities. Because they are related to the students’ own personal situations and because the student has invested some part of him/herself in the activity, it can be useful to use some class time to discuss the answers generated by the class. This offers an additional opportunity for the teacher to encourage authentic speaking and listening in the classroom.

Finally, remember, that as a teacher you are not actually assessing the accuracy of the answers, especially at the higher levels. If you ask a student to discuss their beliefs about how something works or why it is important, there is no right or wrong answer. As a teacher, you do evaluate whether or not they have thoughtfully and fully completed the task and whether their answers show increasing cultural awareness and whether they can and have made cultural connections. Teacher may even decide to use the information provided by students in their activities as discussion topics in the classroom to further cement vocabulary, grammar, and critical thinking skills.

Conclusion

With a strong vocabulary and a good command of grammar, one may be able to communicate accurately. But accuracy, as we have seen earlier, is not enough to guarantee effective communication. As we showed earlier, the meaning of words goes beyond their dictionary definitions. If students have only linguistic knowledge, they may end up with little more than “book knowledge.” Most of us have found ourselves in the situation where our “classroom” language was not enough to communicate in authentic situations. This is often what happens when students learn words and phrases without also learning the corresponding cultural information about using those words and phrases. It is this failing which can often lead to misinterpretations and cultural, as well as linguistic, misunderstandings. To reach high fluency levels, individuals must learn both language and culture.

It is generally accepted that effective communication across cultures needs more than knowledge of the target culture. It also requires an awareness and understanding of one’s own culture. Teachers do not need to take on the responsibility of being an expert in the target culture. They do not need to fear that they are undertrained or unskilled in this field. Instead, teachers need to take on the role of facilitator and do what teachers are well trained to do—create meaningful and engaging lessons to help their students learn. Teachers can and must create activities that enhance intercultural competence if students are to develop higher levels of language proficiency. Not only will these activities allow students to learn about their own culture and the target culture, but they will also activate critical thinking skills and promote higher levels of proficiency based on increased intercultural communicative competence.

Effective communication does not happen by accident. It is hard work and requires careful attention by both the speaker and the listener. Both speakers and listeners must be able to recognize the cultural context in which the communication is taking place in order to attach the appropriate meanings. That means paying attention to more than just the words being spoken. Communicators must also focus on the way in which things are said as well as the paralinguistic cues (e.g., smiles, tone of voice, gestures) being given by the speaker. Being able to stand in the shoes of the other allows speakers to avoid miscommunications by understanding how messages are likely to be understood and to adjust their messages. It helps the listener to understand what the speaker means to say and to respond to the speaker’s intentions which may not always match with the literal meaning of the words being spoken. This skill can only come with a knowledge of both one’s own culture and with knowledge of the speaker’s culture. It puts the focus on the meaning being expressed. In this way, people can communicate more effectively and more meaningfully. Intercultural communicative competence helps individuals to place themselves in the other’s shoes, to see things from the other’s perspectives, to recognize their own biases, and thereby deliver and receive messages that are more likely to be understood as the speaker intended. Intercultural communicative competence creates a truer understanding not only of the message being sent but of the person sending the message. It helps us understand ourselves in this world. By so doing, it helps make the world a little easier for us all to navigate and understand.

References

Allen, L. Q. (2004). Implementing a culture portfolio project within a constructivist paradigm. Foreign Language Annals 37(2), 232-239. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2004.tb02196.x

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (2012). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines. ACTFL. https://www.actfl.org/educator-resources/actfl-proficiency-guidelines

Amirian, S. M. R., & Bazrafshan, M. (2016). The impact of cultural identity and attitudes towards language learning on pronunciation learning of Iranian EFL students. British Journal of English Linguistics 4(4): 34-45. https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Impact-of-Cultural-Identity-and-Attitudes-towards-Foreign-Language-Learning.pdf

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Armstrong, M. (2015). Using literature in an EFL context to teach language and culture. The Journal of Literature in Language Teaching, 4(2), 7-24. http://liltsig.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/LiLT-4_2-Armstrong.pdf

Beach, R. (1998). Constructing real and text worlds in responding to literature. Theory Into Practice, 37(3), 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849809543803

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.) (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, the classification of educational goals--Handbook 1: The cognitive domain. Longman.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). Longman.

Byram, M. (1989). Cultural studies in foreign language education. Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2009). Intercultural competence in foreign languages – The intercultural speaker and the pedagogy of foreign language education. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 321-332). Sage.

Byram, K., & Kramsch, C. (2008). Why is it so difficult to teach language as culture? German Quarterly, 81(1), 20-34.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1183.2008.00005.x

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competency to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication (pp. 2-27). Longman.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approach to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/I.1.1

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing. www.coe.int/lang-cefr

Deardorff, D. K. (Ed.). (2009). The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence. Sage.

Frank, D. (2021). Famous marketing language translation blunders: Unintended puns and campaign blunders. Good Bad Marketing. https://www.goodbadmarketing.com/davidfrank/famous-marketing-language-translation-blunders

Gonen, S. I. K., & Saglam. S. (2012). Teaching culture in the FL classroom: Teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Global Education, 1(3), 26-46. http://www.ijge.net/index.php/ijge/article/view/60/61

Guessabi, F. (2011). Blurring the line between language and culture. Language Magazine. May. https://www.languagemagazine.com/blurring-the-line-between-language-and-culture

Hammerly, H. (1982). Synthesis in second language teaching: An introduction to linguistics. Second Language.

Interagency Language Roundtable. (2012). ILR Skill Level Descriptions for Competence in Intercultural Communication. https://www.govtilr.org/Skills/Competence.htm

Işik, A. (2003). Is ESP a success in the Turkish EFL context? International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 141(1), 255-287. https://doi.org/10.2143/ITL.141.0.2003190

Jennings, Z. (2001). Teacher education in selected countries in the Commonwealth Caribbean: The ideal of policy vs. the reality of practice. Comparative Education, 37(1), 107-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060020020453

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford University Press.

Kuang, J.-f. (2007). Developing students’ cultural awareness through foreign language teaching. Sino-US English Teaching, (12), 74-81. https://doi.org/10.17265/1539-8072/2007.12.017

Liddicoat, A. J., & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. Wiley.

Lim, H.-Y. (2018, Aug. 31). Intercultural communicative competence through critical thinking [Conference session]. The Second National and International Convention of Languages: Language Teaching and Research for Human Development, Chiapas, Mexico.

Lim, H.-Y. (2020). Intercultural communication competence (ICC) assessment development proposal [Unpublished Report]. Office of Standardization and Academic Excellence, Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center.

Lim, H.-Y., & Griffith, W. I. (2002). Idiom instruction through multimedia and cultural concepts. In C. M. Cherry (Ed.), Dimension 2002: Cyberspace and foreign languages: Making the connection (pp. 43-51). Southern Conference on Language Teaching.

Lim, H.-Y., & Griffith, W. I. (2016, Jan. 21). Developing intercultural communication competency in foreign language learning [Conference session]. The Fifth International Conference on the Development and Assessment of Intercultural Competence, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona.

Mizne, C. A. (1997). Teaching sociolinguistic competence in the classroom. Senior Thesis Projects, 1993-2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_interstp2/20

Nagel, D. (2018, August 3). The simple difference between language fluency and proficiency. The MezzofantiGuild. https://www.mezzoguild.com/fluency-proficiency

Omaggio, A. (2001). Teaching language in context (3rd ed.). Heinle and Heinle.

Peck, D. (1998). Teaching culture: Beyond language. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. https://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/files/84.03.06.pdf

Rossen, J. (2018, November 29). Udder success: A brief history of the ‘got milk?’ campaign. Mental Floss. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/565149/got-milk-ad-campaign-turns-25

Savignon, S. J. (2002). Communicative language teaching: Linguistic theory and classroom practice. In S. J. Savignon (Ed.), Interpreting communicative language teaching: Contexts and concerns in teacher education (pp. 1-28). Yale University Press.

Savignon, S. J., & Sysoyev, P. V. (2002). Sociocultural strategies for a dialogue of cultures. The Modern Language Journal, 86(4), 508-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00158

Savignon, S. J., & Sysoyev, P. V. (2005). Cultures and comparisons: Strategies for learners. Foreign Language Annals, 38(3), 357-365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02222.x

Schulz, R. A. (2007). The challenge of assessing cultural understanding in the context of foreign language instruction. Foreign Language Annals, 40(1), 9-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02851.x

Seelye, H. N. (1982). Teaching culture: Strategies for foreign language educators. National Textbook Company.

Sieck, W. R., Smith, J. L., & Rasmussen, L. J. (2013). Metacognitive strategies for making sense of cross-cultural encounters. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(6), 1007-1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113492890

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon. G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence, In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2-52). Sage.

Stern, H. H. (1983). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Tang, Y. (1999). Language, truth, and literary interpretation: A cross-cultural examination. Journal of the History of Ideas, 60(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhi.1999.0010

Thanasoulas, D. (2001). The importance of teaching culture in the foreign language classroom. Radical Pedagogy, 3(3). https://radicalpedagogy.icaap.org/content/issue3_3/7-thanasoulas.html

Zweifel, T. D. (2013). Culture clash 2: Managing the global high performance team. SelectBooks.

[1] If interested see Not just a game: Sport and society in the United States at http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1664/not-just-a-game-sport-and-society-in-the-united-states

[2] For specific information see La mitad de personas en Estados Unidos serán obesas dentro de 10 años (a menos que hagamos esto)[Half of the people in the United States will be obese within ten years (unless we do this] at https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2019/12/19/la-mitad-de-personas-en-estados-unidos-seran-obesas-dentro-de-10-anos-a-menos-que-hagamos-esto