Introduction

Vocabulary is an essential element of any language. However, teachers usually prefer teaching grammar over vocabulary. As a consequence, learners face problems to communicate when they do not know a specific word for a particular context. Therefore, teachers should focus their practice on providing appropriate activities for students to develop their receptive knowledge through reading and listening, and productive knowledge through writing and speaking. Additionally, teachers should be aware of the fact that knowing a word involves not only its most frequent meaning, but also all its features. So, teaching vocabulary more effectively requires the teacher to consider the word frequency, the context in which it may be found, and the features or aspects related to knowing a word. The teacher also needs to think in advance about the interaction among students to make acquisition to happen, the amount and quality of learners’ involvement, the receptive and productive knowledge involved, the teaching methodology, and the tasks through which vocabulary is going to be made more comprehensible and meaningful for EFL learners. This article is divided into two sections: the first part covers the previously mentioned aspects above and their implications for vocabulary acquisition, and the second section includes sample focused tasks which follow these considerations.

Frequency

Since vocabulary is necessary for both understanding and using a language, it represents an essential component in English teaching. However, there have been many myths about second language vocabulary that have hindered the development and use of teaching methodology that enhances vocabulary acquisition. The claim that “the more vocabulary a learner knows, the better s/he can perform with the language” needs to be reconsidered because it is not only knowing more words, but knowing all the aspects related to those words (see below what knowing a word involves). Nation (2004) suggests, for example, teaching first the most frequent words and as the learner progresses in her/his level of language, s/he may continue to learn the least frequent words. Nation bases his argument on research that shows that a small number of words occur very frequently and if the learner acquires them, s/he can understand and interact accurately well with texts and people. However, in an EFL setting that hardly provides real communicative opportunities beyond the classroom, both the teacher and students may not know some words for particular contexts, such as the specific food or ingredients that are offered in a restaurant and that appear in the menu. Then, they are obliged to learn these words in order to be able to understand and perform well in class and later in the context, when using a real menu to order food. Therefore, it is important to start teaching the most frequent vocabulary in a contextualized way so that students can store it in their memory and retrieve it for later use in communicative interactions.

Context

We learn words better when they are acquired in a meaningful context. Firth (in Widdowson, 1995) states that “the study of meaning was the study of language use” (p. 9) and he suggests a convincing definition of context as a suitable construct to apply to language events and that includes participants with their non-verbal and verbal actions, relevant objects, and the effects of verbal actions. According to this definition, vocabulary must be immersed in a context for students to make meaningful connections to their previous knowledge and to be able to acquire those words and to use them in future situations. When food is ordered at a restaurant, for example, there is a need and also a response to that need. So, knowing in advance the words necessary for that kind of context and what people are involved in this context will give students the opportunity to be prepared for a challenging and real experience. Then, teachers must understand that “the context is determined by setting or place and people involved in the communication” (Lee & VanPatten, 2007, p.246). So, if the teacher is discussing a laboratory, the teacher and students are expected to study words like Bunsen burner and beaker (Blachowicz & Fisher, 2002, p.19).

Interaction and Involvement

Interaction through group work is another aspect the teacher has to take into consideration when teaching vocabulary. Widdowson (1995) suggests group work because “it allows learners to adopt addresser and addressee roles in co-operative endeavor in the negotiation of meaning” (p.17) and he also recommends instead of exercises to use tasks for solving problems by means of language. For teaching vocabulary, we need also to analyze Laufer and Hulstijn’s (2001) Involvement Load Hypothesis in which they claim that three motivational and cognitive dimensions are involved: need, search, and evaluation. They refer to need as the motivational factor that can make people direct their effort to achieve their goals. This need or motivation may be directed toward the language, to the people who speak the language, and also to the context in which language is spoken. Search is the attempt to find the meaning of an unknown word by using a dictionary or asking another person who knows the meaning such as another peer or the teacher. Lastly evaluation refers to the fact of choosing among many words the most appropriate one that fits into a specific context. The more the teacher includes these dimensions in his/her activities, the more involved students will become and the better they will acquire the target vocabulary. Therefore, “…words which are processed with higher involvement load will be retained better than words which are processed with lower involvement load” (Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001, p.15).

Knowing a Word

The process of vocabulary acquisition is complex. Knowing a word goes beyond knowing only its more frequent meaning. According to Nation (2001), “there are many things to know about any particular word and there are many degrees of knowing” (p.23). Nation (1990) and Richards (1976) claim that for knowing a word it is necessary to know its orthographical and phonological form, meaning, grammatical aspect, associations, collocations, frequency and register (in Schmidt & McCarthy, 1997, p.4). Folse (2007) adds other aspects that include polysemy (several meanings for the same word), connotation (actual meaning) and denotation (idea suggested in a context). So, anytime the teacher wants to present a new word, s/he has to do further research about all of the features of that word or set of words before planning the lesson. For example, Anderson and Baddeley (in Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001) claim that paying careful attention to the word’s features will lead to higher retention than by processing new lexical information of only one or two of the features.

Receptive and Productive Knowledge

This distinction depends on the skills involved in each case. For developing receptive knowledge, learners usually use their listening and reading skills, whereas for productive knowledge, they use their speaking and writing skills. Nation (2001) provides a set of aspects of what is involved in knowing a word regarding: form (spoken, written, and word parts), meaning (form and meaning, concept and referents, and associations), and use (grammatical functions, collocations, and constrains of use). Table 1 provides more information. Thus, if the teacher wants her/his students to know a word, then s/he has to consider all the features of the word and design tasks that enhance both types of knowledge.

R=receptive knowledge, P=productive knowledge

Table 1. What is involved in knowing a word (Nation, 2001, p.27).

Task-Based Language Teaching and Tasks

Having discussed the different aspect for teaching new vocabulary and what it means to know a word, I now shall describe the methodology that involves task design. According to Skehan (1998), a task must have four criteria: 1) Meaning is primary; 2) There is a goal to be accomplished; 3) The task is outcome evaluated; 4) There is a real-world relationship. Ellis (2003) defines a task as:

…a work plan that requires learners to process language pragmatically in order to achieve an outcome that can be evaluated in terms of whether the correct or appropriate propositional content has been conveyed. To this end, it requires them to give primary attention to meaning and to make use of their own linguistic resources, although the design of the task may predispose them to choose particular forms. A task is intended to result in language use that bears a resemblance, direct or indirect, to the way language is used in the real world. Like other language activities, a task can engage productive or receptive, and oral or written kills, and also various cognitive processes. (p.16)

From the definition we can summarize that for working with tasks we need to design materials or activities that focus on meaning by incorporating a gap for students to close. This gap provides a need and also motivates students to find the information to complete the task. The task can be unfocused when it is designed without addressing a particular form, or focused when it is targeting a specific form (Ellis, 2003). The task must require learners to engage in either a real-world or artificial activity, but the language outcomes of the task must refer to real-world communication interaction. The tasks require learners to employ both receptive and productive skills. Learners are also required to evaluate information in order to carry out the task. It offers a well defined communicative outcome and many opportunities for negotiation of meaning. So, tasks have all the features needed for encouraging students to acquire vocabulary and use it in the class context and take it to real-world environments. The main advantage of using this approach according to Newton (2001) is that “it enables learners to develop strategies for managing new vocabulary while also maintaining a communicative focus” (p.30).

Focused Tasks for Teaching Vocabulary to EFL Students

The following tasks were designed taking into account the framework for describing tasks suggested by Ellis (2003). This framework contains: 1) A goal which is the general purpose of the task; 2) input that refers to the information provided to the learners through the materials; 3) conditions that refer to the way in which the information is presented; 4) procedures that involve the group interaction; and 5) predicted outcomes that denote the final product.

Since the purpose of this article is to provide the readers with some ideas of how to develop tasks for teaching vocabulary, the types of tasks suggested are focused tasks which target specific words extracted from a randomly chosen restaurant menu. According to Johnson (in Ellis, 2003), “focused tasks are of value to teachers because they provide a means of teaching specific linguistic features communicatively” (p.142). The tasks cover the different features of words listed by Nation above (form, meaning, and use), and take into consideration the learners’ load of involvement by providing the factors of need, search, and evaluation. In all of the tasks learners are involved in negotiation of meaning. According to Pica (1992), this negotiation of meaning helps learners to: 1) obtain comprehensible input by splitting the input in smaller pieces that can be more easily processed; 2) obtain feedback on their production; and 3) manipulate and correct their output (Ellis, 2003). The tasks suggested are not necessary sequenced rather they offer examples of how teachers can design their own tasks to deal with vocabulary.

The tasks are designed based on the options for dealing with new vocabulary suggested by Newton (2001) and that can be used in the pre-task, in task, or post-task stages of a lesson. Table 2 provides more information on these options.

Table 2.Options for targeting unfamiliar vocabulary in communication tasks (adapted from Newton, 2001, p.31)

Since one of the tasks’ features is to provide a real context, learners are encouraged to deal with a restaurant’s menu and the final goal of the lesson is for students to be able to offer and order food after they have acquired some unfamiliar words. For doing this, they need to know some words that are repeated several times. All the tasks were designed for teaching these words to low intermediate level students. This class was considered to have an uneven level of fluency and in which the process of scaffolding may happen when some students assist others in performing an action that they could not do alone. Some of the advantages of scaffolding according to Wood, Bruner, and Ross (in Ellis, 2003) are: 1) creating interest in the task; 2) facilitating the task; 3) keeping interest for achieving the goal; 4) helping identify differences between outcomes and the final solution; 5) keeping others away from frustration; and 6) providing a sample of the final production.

Pre-Tasks

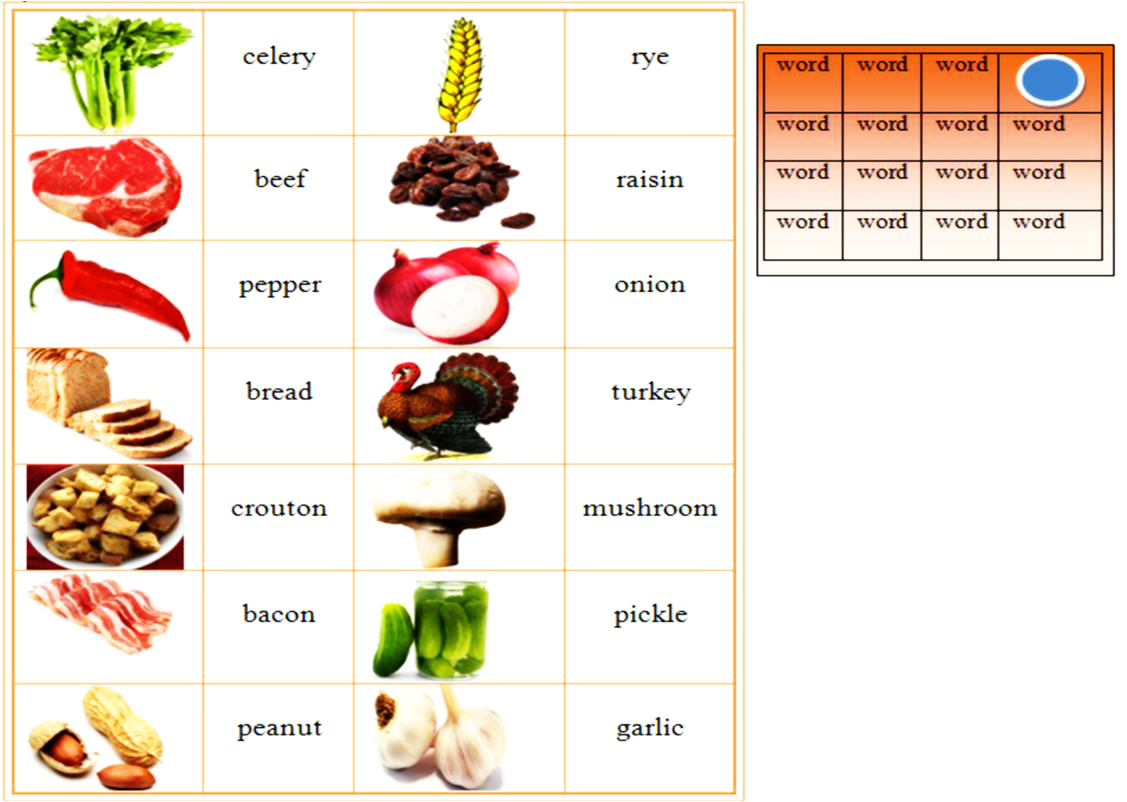

The advantage of presenting the vocabulary in the pre-task stage is that the teacher is giving the learners the language they need and students will be able to perform better in the following tasks. The words to be taught are: shrimp, bacon, celery, rye, cucumber, bread, onion, sesame, olive, mushroom, peanut, gravy, turkey, garlic, pickle, beef, pepper, clam, and raisin.

Example 1 Word Web

Task A Prediction. In this task, students form groups of four. They are given a word web to add four words related to a specific part of a menu (see the word webs below). Each student works individually with a web for some minutes. Then, they share their web with the rest of the teammates and help each other to have the words required in the webs. This word web helps students to organize words according to semantic categories (Newton, 2001) and the possibility to add more words as they move along in the lesson. This type of task promotes group work and a context for reading and understanding the menu.

Figure 1. Word webs

Task B Opinion Exchange. After students finish their prediction task, they are asked to share their results with other teams in order to give and receive feedback and have their word webs as complete as possible. After that, one group is asked to give their answers and the rest of the class can provide corrections or suggestions. This task is also called jigsaw because it requires students to share all their outcomes to complete one in common. In this task the focus is on teaching word form because students pay attention to spelling so they can write the words to complete the web. Since the web refers to words related, students can see the relationship among the words and have a general classification of new vocabulary.

.jpg)

Figure 2. Opinion exchange of word webs

Example 2 Cooperative Dictionary Search

Task A. Jigsaw. A jigsaw task is also called a split-information task in which a person or group in the class has some information that the other students do not have but need. In order to complete the task they have to put their information together. The main purpose of this task is to have all students communicating and exchanging information (Willis & Willis, 2007). This task focuses on meaning of the words by looking the meaning at the dictionary and providing a simpler description of the word that can provide the other students with more details about the words and recognize some of their features even without a picture. For doing so, each student is given a word from the list of twenty (maybe written on a piece of paper) and asked to look up its definition at the dictionary. After having the meaning, the student has to write a description of the word using a simple sentence next to the word and share it with the rest of the class. The goal is to complete the chart below by collecting all the information from the rest of the class.

Chart 1. Jigsaw task

In-Tasks

Example 1 Interactive Glossary

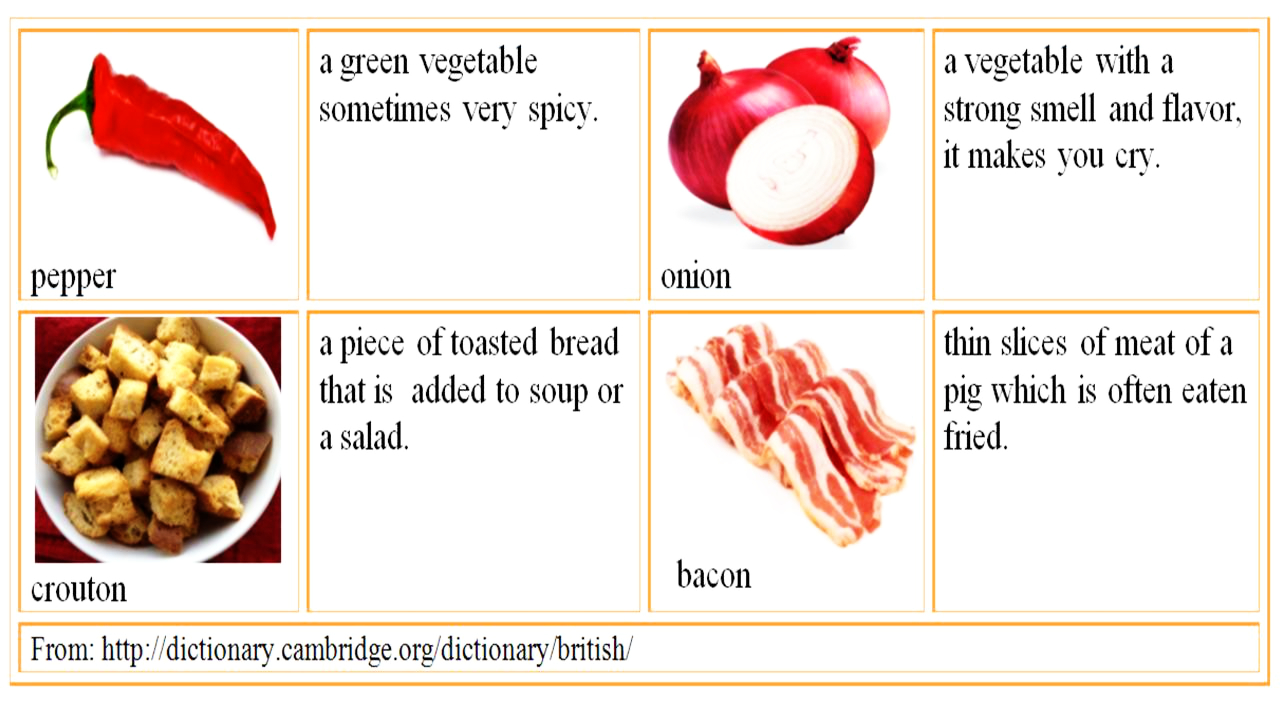

Task A Information Gap (one-way). Students get into groups of four and each one is given a set of five words (in total twenty in the group). They face the cards down (see below examples) and whenever someone in the group needs to know a new word, the student who has it, reads the description for the others to guess the word. Another option is to give hints about the use, color, odor, or other characteristics that help his partners identify the word. For example:bacon: “is a kind of meat that you usually eat with eggs”.

This task is called one-way information gap because one person has the information and share it with another when required (see Figure 3). The advantage of this task is that students have to do something with the word before using it. The pictures facilitate the owner to understand the meaning and be able to establish some connections with the context and other target words.

Figure 3. Vocabulary cards for one-way information gap.

Example 2 Model to Hear and Pronounce

Task A Information Gap. This task “works on the idea that learning to produce new sounds may improve the learners’ ability to hear them correctly” (Nation & Newton, 2009, p.87). However, instead of the teacher being the model who says the words and asks learners to repeat after the teacher, the students have to pronounce the words and the teacher reinforces or corrects. The task is a lottery game in which students are asked to make a grid (4 x 4 squares) in a piece of paper. The teacher writes the twenty target words on the board and asks students to choose sixteen and write one on each square randomly. The teacher brings flashcards of the target words with the picture on one side and the spelling on the other and tokens or beans to the class. The teacher explains that every time they listen to a word they put a token/bean on the corresponding square until they complete the card. But, instead of calling out the words, the teacher elicits its pronunciation from students and provides reinforcement or correction if necessary.

Task B Information Gap. The students are asked to form groups of four and exchange their lottery cards with their teammates (see Figure 4). They are given a set of small flashcards to continue with the game. Each student takes turns to flip over one card at a time and say the word out loud for the others to fill in their lottery card. This task is useful for practicing pronunciation and matching pictures, spelling and sound. Students will repeat the new words with a purpose and the teacher may walk around to provide help or to check mispronunciation. The advantage of having a game as a task is that it adds the fun factor that can catch learners’ attention and enhance acquisition.

Flashcards Lottery card

Figure 4. Vocabulary flashcards and lottery card

Example 3 Negotiation

Task A Information Gap. This task is specially designed to deal with collocations which are words that are commonly attached to the target words. For example, fast collocates with food. For helping students notice the word or set of words that collocate with the target word, they are placed in bold letters and located before or after the target word. This task is a two-way task in which both students have part of the information and need the other partner’s information to complete the task. By splitting the information in two parts students can cover more vocabulary than any individual learner (Newton, 2001). They are asked to first write the word that corresponds to the pictures. Once they have these words, they exchange information that does not have pictures. They need to complete both cards because they will need this information for the next task.

Figure 5. Information gap.

Task B Decision Making. Although this task permits a number of possible outcomes (Ellis, 2003), it requires students to agree on a solution to a problem. The teacher presents a situation for students to provide the best solution using their previous knowledge. For example, “Today is your birthday and you ask a friend to help you organize a party. You invite some friends to your house so you need to prepare something to eat. You decide to make one main entrée, one salad and one soup for ten people using the ingredients from the previous task and complete the table below in order to have a list of what you need”. The following is the form that would be used with this activity.

For example: ten sticks of celery…

Chart 2. Decision making task.

Example 4 Problem solving. This type of task offers students the possibility to give their opinion or to agree on a solution for a specific problem. For vocabulary teaching, the task may be focused on using the new words for solving a problem in which a lot of discussion is involved. The problem has to be within students’ experience and directly affecting them. In order to solve the problem, students need to have time to think beforehand and maybe breakdown the discussion in a set of mini-tasks. According to Willis and Willis (2007), some of these mini-tasks might include: listing the effects of the problem, comparing personal experiences, sharing and comparing possible solutions, writing notes for a presentation of reasons, writing a final proposal that others can listen to or read.

Task A Discussion.The teacher is planning a party and needs to know students’ preferences so that he can decide on what food could be appropriate to include in the celebration. Students are given individually the table below and are asked to choose three items they like and three they do not like from the list of twenty target words (including name and picture). They are asked to include their reasons for choosing the items. Then they compare their answers in pairs and try to convince each other to have the same options. The final goal is to have only one table that includes only three good and three bad options. The following chart would be used.

Chart 3. Discussion task.

Task B. Problem Solving. Students express their opinion in the class and try to convince the others of the best choices. The final goal is to have five items they can have at the party and five they definitely do not want to eat.

Chart 4. Problem solving task.

Post-Tasks

Example 1 Vocabulary Logs. A vocabulary log is a chart or a list of new words that learners found throughout the lesson. They write them down including some information about the words to facilitate future revision. One sample of this log is provided by Newton (2001).

Chart 5. Vocabulary log (Newton, 2001).

The advantage of logs is that they encourage learners to be responsible of their own learning and write the words they found to be useful for future lessons. Other ideas apart from logs suggested by Newton include checking different meanings of the same word at the dictionary, making flashcards and using the words for writing new sentences, creating a story using the words from the log and telling it to someone or even to the class, and as a tool for testing each other in pairs before a test, or simply as a personal challenge.

Conclusions

Focused tasks put together all the elements necessary to facilitate vocabulary acquisition, integrating all of the features that are part of knowing a word. The teacher can start by choosing the context (restaurant), the language function (ordering food), the material where s/he is going to take the words from (an authentic menu), make a list of the target words according to their frequency (more to less frequent), have students work individually and then interact in groups in order to exchange information and close information gaps. The teacher must provide lots of opportunities for developing receptive knowledge (through listening and reading) and productive knowledge (through speaking and writing) by having students creating their own learning and producing samples of language acquisition.

The activities presented in this article come to be a valuable reference for teachers who want to adopt TBLT (Task Based Language Teaching) as their teaching approach, or for those pre-service teachers who want to have ideas about how to deal with unfamiliar words and their different features. Knowing a word is not anymore knowing only its translation, but knowing its form, meaning and use in a specific context and with a particular purpose.

References

Blachowicz, C. & Fisher, P. (2002). Teaching Vocabulary in all Classrooms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching. New York: Oxford University Press.

Folse, K. (2007). Vocabulary Myths. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Laufer, B. & Hulstijn, J. (2001). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: The construct of task-induced involvement. Applied Linguistics, 22(1), 1-26.

Lee, J. & VanPatten, B. (2007). Making Communicative Language Teaching Happen. Chicago: McGraw-Hill.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001). LearningVocabulary in Another Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I.S.P. & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. New York: Routledge.

Newton, J. (2001). Options for vocabulary learning through communication tasks. ELT Journal, 55(1), 30-37.

Schmidt, N. & McCarthy, M. (1997). Vocabulary, Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 17(1), 38-62.

Widdowson, H.G. (1997). The context of the classroom. BELLS Barcelona English Language and Literature Studies, 8, 9-21.

Willis, D. & Willis, J. (2007). Doing Task-Based Teaching. New York: Oxford University Press.