Introduction

The Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (PNIEB) is part of an ambitious educational policy which aims, in the long run, to produce more Mexicans who have communicative competence in English. However, the goals of the PNIEB are not only framed in terms of linguistic gains. According to the Fundamentos Curriculares del Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (SEP, 2010, p. 54):

UNESCO has indicated that educational systems are to prepare students in order to face the new challenges of a globalized world, in which the contact among multiple languages and cultures becomes more and more common every day. In this context, the [Mexican] educational system is compelled to help students understand the diverse cultural expressions in Mexico and the world.

To this end, the program articulates the general goal of the program, that students completing their basic education “… will have developed the necessary multilingual and multicultural competencies to face the communicative challenges of a globalized world successfully, to build a broader vision of the linguistic and cultural diversity of the world, and thus, to respect their own and other cultures” (SEP, 2010, p. 54). The Fundamentos Curriculares document also lists a range of non-language learning objectives for the program. For example, the curriculum states the general goals for the first four years of the program (grades K-3) as (SEP, 2010, p. 22, emphasis in original):

1. Acknowledge the existence of other cultures and languages.

2. Acquire motivation and a positive attitude towards the English language.

3. Begin developing basic communication skills, especially the receptive ones.

4. Reflect on how the writing system works.

5. Get acquainted with different types of texts.

6. Start exploring children’s literature.

7. Use some linguistic and non-linguistic resources to give information about themselves and their surroundings.

The reader will note that besides the third and seventh points, most of the objectives do not refer to language skills, but rather competencies that can be achieved through studying a foreign language, but are not themselves linguistic competencies[1]. The objectives also reflect the argument (Woodgate-Jones, 2009) that a key aim of early L2 instruction in foreign language contexts like Mexico should be intercultural understanding. Therefore, this study is framed as a qualitative impact study: it is focused on documenting how well the PNIEB in one state, Aguascalientes, has been able to promote non-linguistic learning objectives. In order to examine the impact this state’s early foreign language program is having on students’ learning and development more broadly, we used a framework called the “Five Cs” developed by the American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages (ACTFL, 1996).

First, we will review some background literature in the burgeoning area of early foreign language education. Then we will outline the approach we employed in this study, including giving background information on the program in Aguascalientes, explaining the Five Cs framework, and describing our methodology. We use the Five Cs framework to present our findings, and the conclusion highlights some of the most important non-linguistic impacts that the program is having.

Primary English Language Teaching

The PNIEB in Mexico should be understood as a language policy that is part of wider global trend (Sayer, forthcoming). This trend is characterized by the increase of English language instruction in public schools, and its introduction earlier in the curriculum (Enever & Moon, 2010). This second characteristic is called PELT: primary English language teaching. The advent of English as an international language has been concomitant with the rise of globalization and the need for a global lingua franca to facilitate the exponential growth in the exchange of goods and information worldwide; however, PELT is still a relatively recent phenomenon, and has seen most of its growth in the last 10 years.

Especially amongst countries with developing economies, PELT is seen as necessary to ensure that the next generation’s workforce will have the requisite communication skills to allow the country to compete in the global marketplace[2]. In the emerging economies of Southeast Asia, English has become a mandatory part of the primary curriculum in places like Bangladesh (Hamid, 2010), Malaysia (Ali, Hamid & Moni, 2011), and Vietnam (Hoa & Tuan, 2007; Nguyen, 2011).

In Latin America, several countries have already adopted PELT as part of their basic public education curriculum. In Colombia, the government created the ambitious Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo (PNB) in 2004 (Herazo, Rodríguez & Arellano, 2012). The authors describe several difficulties in implementing the PNB that parallel the Mexican experience with the PNIEB: (1) it was directed in top-down fashion by the Ministry of Education by including English as part of the national curriculum; (2) the program is justified in terms of the discourse of global communication and competitiveness as necessary for national development; (3) the English curriculum is organized along Common European Framework of Reference of Languages; and (4) the program has had serious difficulties with funding and finding qualified teachers. The program in Chile, started in 2004, is called the “English Opens Doors Programme” (Matear, 2008). Argentina began a similar program in 2006 starting in fourth grade (Zappa-Hollman, 2007). Both authors describe problems like those encountered in Colombia and Mexico.

The Five Cs Framework

The analytic framework of this study is aligned with the general rationale for foreign language education in Mexico. The American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) recognized that foreign language learning is a complex activity. Beyond acquiring language skills, vocabulary, and grammar, learning an additional language involves engaging with new ways of thinking, values, customs, and norms of interaction. In short, there are many social and cultural elements of L2 learning. Therefore, ACTFL developed a conceptual framework that reflects the complexity of learning (and teaching) a foreign language. The framework is intended to provide teachers, curriculum planners, and researchers with a tool that can inform their work. This framework is articulated in the Standards for Foreign Language Learning: Preparing for the 21st Century (ACTFL, 1996) as the “Five Cs”: communication, cultures, connections, comparisons, and communities.

The ACTFL framework provides a heuristic for understanding the wider educational and societal impact on the individual student and of the foreign language as a whole. Thus, it is well suited as an analytic lens, since the PNIEB is based on a sociocultural approach that emphasizes constructing knowledge and understanding through social practices across three learning environments (Vargas Ortega and Ban, 2011).

Research questions

The general goal of the study is to examine the ways in which the English language program in public schools has impacted its constituency. We have articulated the overarching research question as:

How has the PNIEB impacted the education of primary school students in Aguascalientes?

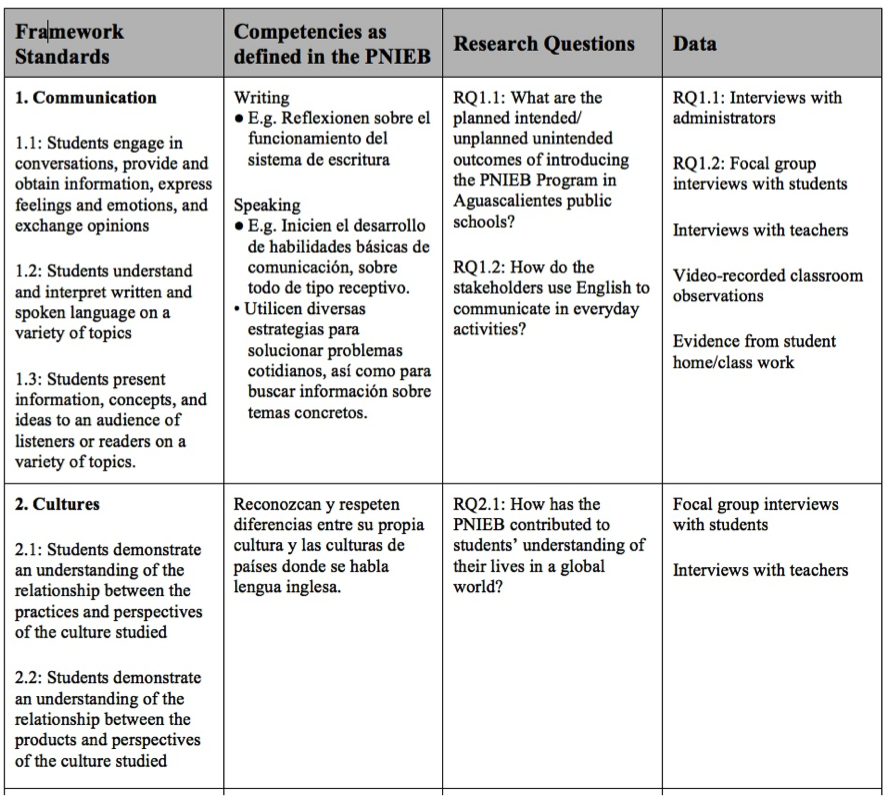

In order to investigate the possible areas that a foreign language program can have social and educational impacts, we posed a series of research questions framed by the “Five Cs” framework cited above. Additionally, we added another category – curriculum – that responds to specific aspects of the PNIEB methodology as part of the larger Reforma Integral de Educación Básica (RIEB) that moved towards a sociocultural pedagogical approach based on social practices.

Research methodology

This study was designed to render a qualitative picture of the overall impact the English program in Aguascalientes has had on students’ education and learning. The qualitative methodology enabled the researchers to adopt a flexible, inductive approach, one that privileged the perspectives and insights of the stakeholders. Therefore, the complete study will rely on participant interviews and classroom observations to generate data to answers the research questions, as shown in Table 1. Note that for the portion of the study we are reporting on here only includes the interview data.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Table 1: Research Design: Overview of framework, research questions, and data

Data Collection

Data was collected from three sources: (1) Semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders: teachers, students and administrators, (2) classroom observations of English lessons, and (3) supporting documentation: student work and other documents related to the PNIEB. The diverse data types allowed the researchers to triangulate their analysis; however this article only presents the interview data. The project manager organized the permissions with the ministry and schools, and the consent forms for student participants.

Data were collected over three weeks in fall 2012 by the field researchers, and subsequently all interviews were transcribed. Although guided by the protocols, the interviews were semi-structured, in order to strike a balance between asking a uniform set of questions tailored to the research objectives, and including an element of exploratory research by allowing for open-ended responses (King & Horrocks, 2010). For each school researchers conducted five interviews, and additionally interviewed supervisors:

1. Focus group interview with 4-5 children (grades five or six)

2. Individual or focus group interview with 2-3 PNIEB teachers

3. Focus group interview with parents (one interview per school)

4. Interview principals

5. Interview titulares (classroom teachers)

6. Interview PNIEB supervisors

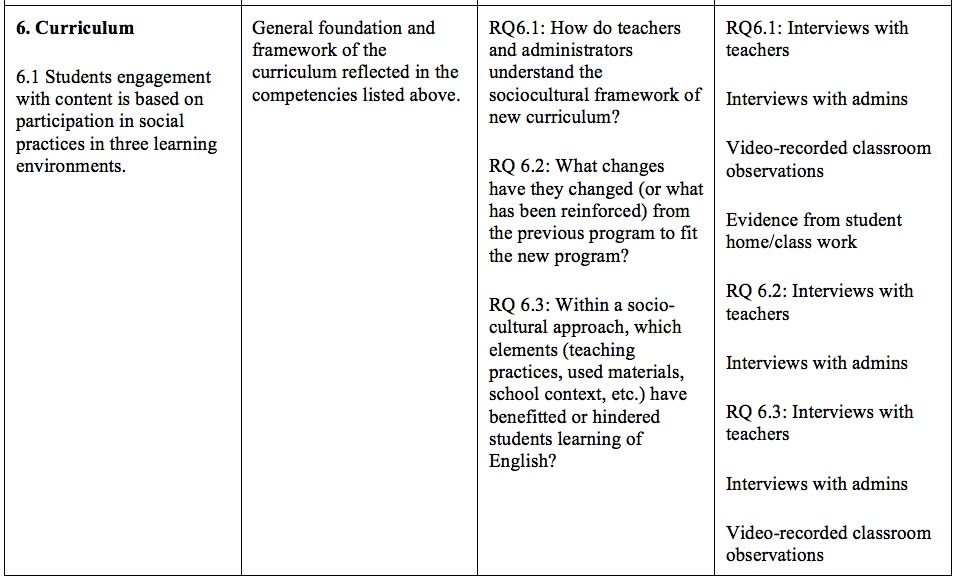

The interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed by the local research support team, as shown below in Table 2. This generated a total dataset consisting of:

· 107 interviews with 199 participants

· 31 video-recordings of classes with 31 different PNIEB teachers

· Documentary evidence (photographs, lessons plans, etc.)

Table 2: Interviews by participant

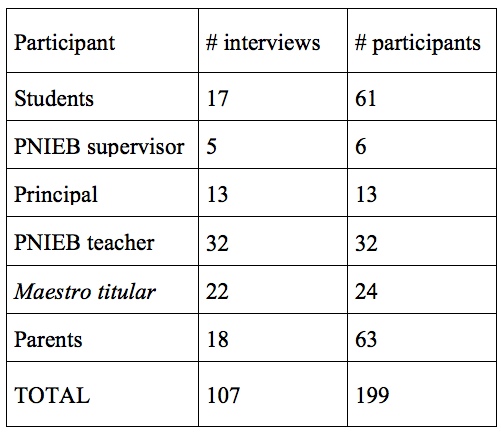

Selection of Sites

Patton (2002) suggests there is no absolute correct number of participants in any given qualitative study. More appropriately, the participants are purposefully selected as representative of the groups under study. The selection of sites in the present study is purposive in that they are carefully chosen to include all of the criteria in the following table, such that the overall sample includes schools that reflect the diversity of educational contexts within the state of Aguascalientes. Therefore, the strategy for selecting schools will be to include the greatest diversity possible. In total, 15 schools were chosen:

Table 3: Criteria and plan for selection of school sites

Data Analysis

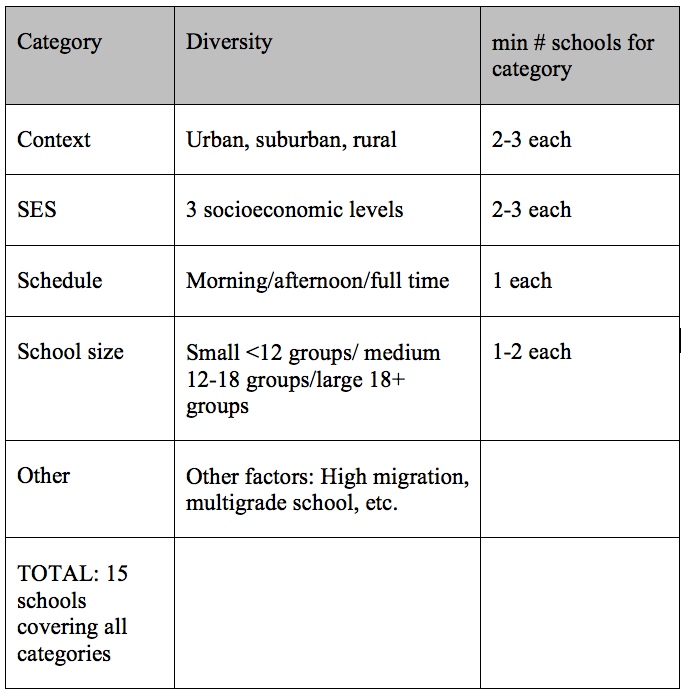

After the transcripts were completed, they were then coded and analyzed by the authors utilizing NVivo 9.0 qualitative research software to do qualitative content and emergent analysis (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2011). We used the competencies specified in the PNIEB and the ACTFL framework as a starting point in our investigation, for designing interview and observation protocol and as a lens for data analysis. However, since we did not presume to be able to conjecture the possible impacts the program may have, we took a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), in that the data were analyzed inductively and recursively until saturation was reached in the recognition of patterns amongst emerging themes. Additionally, the design allowed the researchers to triangulate across three types of data, as well as across the participants and sites, allowing researchers to gauge, qualitatively, the relative importance or degree of impact of the categories identified.

As we coded using the manual, we continued to refine the categories as more themes emerged through the analysis. After coding all 107 transcripts and resolving the discrepancies amongst our analyses, we generated the following conceptual map of our categories:

.png)

Figure 1: Conceptual map of analytic categories

Participants’ perspectivesIn order to obtain a complete picture of the PNIEB in Aguascalientes, the study considered the perspectives of all the stakeholders involved: the English teachers, titular teachers, principals, supervisors, and especially the students and their parents. In general, the opinions and experiences of those who participated in the study were positive about the program; they identified the elements they considered to be its strong points, but also made observations about the aspects of the program they felt could be improved.

The students

The students spoke frankly and honestly about their experiences in English class, and expressed their opinions about their teachers. Since the students interviewed were fifth and sixth graders, most had begun studying English in the state program, and then had moved into the PNIEB two years prior. However, other than noticing that “antes teníamos libro de inglés, pero ya no tenemos, pues trabajamos con puras copias,” the students did not perceive a big difference between the prior state program and the PNIEB. Generally, their view of English class was very favorable:

Omar: Porque a veces la “teacher” nos deja juntarnos en equipos y pues a mí me gusta juntarme en equipos con mis amigos, o también nos pone a hacer cosas divertidas como por ejemplo sopa de letras que nos puso el otro día y también me gusta porque como muchas páginas de internet vienen en inglés, pues me figura mucho aprender inglés para saber qué dicen esas páginas.

The positive attitude they expressed about their classes was also reflected in their view of the English language both in and out of school, as reflected in the following comments:

Sebastián. Antes tenía un X-Box, y todos los juegos eran de puro inglés, y ya pues nomás lo leía, pero lo que le entendía…

Ent: ¿Sí entendías algo?

Sebstián: Algunas cosas.

Giovany: Yo tengo un juego en inglés, y ahora que ya estoy aprendiendo inglés, ya lo estoy jugando más seguido.

On the whole, the students’ comments affirmed that the PNIEB is meeting its objective of getting children interested in learning a foreign language; their views reflected a positive attitude towards their class and the language. While adolescents and adults often perceive the grammar and pronunciation of a foreign language like English as an obstacle, owing to their high affective filter, no student in the present study described English as “difficult,” but rather many stated that using the language to do conversation (like role plays) was their favorite activity in class.

Parents

Almost without exception, the parents support the inclusion of English as part of the school curriculum. This support was consistent across urban, suburban and rural contexts, and with parents of different socioeconomic levels that we interviewed. One mother contrasted how it was to study English in her time with the acceptance that it has now as “algo normal”:

M1: Ellos ya lo van llevando más natural, a diferencia de nosotros que… ellos ya como nosotros aprendemos el idioma; ellos desde chicos lo van implementando y ya es algo normal.

Other mothers reinforced this view, explaining that English is now something quotidian:

M1: Como en los 80s que cantaban las canciones que “wachawachabean”.

M2: ¡Ándele! jejeje… [risas]

M1: Pero él las oye ahora y…

M3: Pero fíjate que, a diferencia de esa época, yo me acuerdo que uno las escuchaba y todo, pero no le entendías a la pronunciación; y los niños de hoy, yo no sé cómo le hacen, pero le entienden, que cantan y le entienden a la pronunciación, pronuncian tal cual la palabra.

M4: Sí, porque ya es algo más cotidiano para ellos. O sea, y es algo que están viviendo; porque yo lo vivo con mis hijos.

M3: Sí, ellos aprenden la canción y la letra también la cantan en inglés.

M4: Y uno nomás como que le sigue.

M3: Sí, nada más le tarareas.

The majority of the focus groups of parents had a positive view of the PNIEB (in 12 of 15 schools we visited). One mother who had entered her daughter’s classroom during the English lesson came away with a favorable impression of the English teachers’ pedagogy:

M2: Por ejemplo en nuestro grupo la semana pasada hubo algún convivio para la maestra.

Ent: ¿De inglés?

M2: No, para la maestra de grupo […] pero nos tocó hacerlo en la clase de inglés, entonces estaban los niños pues obviamente porque iba a ver fiesta e iba a ver convivio [ríe] iba a ver…

Ent: Pastel.

M?: Sí, sí pastel y cosas, estaban muy exaltados y muy acelerados y la maestra obviamente todo en inglés… Yo no supe ni que les decía.

Todos: [risas]

M2: Y los controló, los controló totalmente y todo, todo, absolutamente todo se los decía en inglés.

One father expressed his satisfaction at what he felt is the excellent level of English in the public schools in Aguascalientes:

Tengo familia también de Estados Unidos y ahora que vinieron, sí hicieron mucho ese comentario porque me dijeron “y ¿sí sabe hablar inglés?”. Le digo, “sí”; me dicen, “¿la tienes en una escuela privada”; le digo, "no, en una escuela pública"; "¿y ya les dan?"; les digo, “sí, les dan”. Entonces la empezaron a interrogar de que los números, la partes del cuerpo, cántame una canción, y se sorprendieron porque estaba muy chiquita y más porque me decían, “es que estás en una escuela pública"; le digo, "sí, pero aquí, lo que es Aguascalientes ya tiene mucho tiempo que está en escuela pública y lo que es en la República ya se está implementando”.

However, in three of the 15 schools in the sample, parents had criticisms of what they perceived as deficiencies in the program. One father insisted on the importance of English, but criticized what he felt was the inadequate progress of his children in English class:

PF1. [muletilla] Bueno yo básicamente pienso que el programa o el nivel que les dan en la escuela a los niños, pues la verdad para mi punto de vista se me hace muy poco lo que les enseñan a los niños de inglés, me gustaría a mí que fuera más amplio, que les dieran un poquito más de inglés, no sé, más horas porque el inglés en esta vida ya es primordial, […] ya es realmente necesario en esta vida y más para los trabajos, etcétera. O sea ahorita el inglés ya no es… [muletilla] el que lo hablara un lujo, ahorita es necesario que ya lo hablen los hijos, es lo que yo opino, que les faltaría que dieran un poquito más… más amplio o no sé eso con quién se tenga que ver pero la verdad sí me gustaría que fuera más, un poquito más amplio.

Another mother criticized the program’s approach, explaining that she felt the children had too few opportunities to actually practice conversing in English:

M3. Yo creo que les falta un poco de conversación, de que les enseñen a conversar porque sí saben palabritas u oraciones pero memorizadas, pero uno los lleva a algún lado y les dices: pídelo en inglés y no, no lo saben armar y también yo les he sugerido año con año el vocabulario porque en otra escuela en donde los llevaba antes sí les daban vocabulario y con eso avanzaban mucho y aquí no les dan nada de vocabulario.

Ent. ¿En otra escuela pública también o escuela particular?

M3. No, colegio particular.

There are two important points about these critiques. First, they represent a minority of the parents interviewed about the teachers and the program, especially the comment about the teacher’s methodology not being very “communicative.” Secondly, the above opinions corresponded to parents in schools with a higher socioeconomic level. It seems then that these parents make direct comparisons of the PNIEB with the type of teaching and level that children in private schools achieve. Notwithstanding, the classroom observations and interviews with teachers carried out as part of this study reveal that this goal is not unrealistic, and that it may in fact be a good thing that the parents are setting the bar so high for the program.

The impact of English in primary education

The full report commissioned by the state ministry includes an extensive list of the impacts of the PNIEB, corresponding to the research questions and the modified Five Cs framework. For the purposes of this article, we will include some of the most prominent findings of the study.

The impact of the PNIEB beyond the classroom

The research questions related to communication included the impact of the PNIEB on the students’ use of English in and out of the classroom (RQ 1.1 and 1.2, see Table 1). Our analysis suggests that there seems to be a direct cause-and-effect relationship between studying English in the PNIEB and the students’ use of the language in social contexts, and suggests that the linguistic gains students make in English is associated with other sociocultural impacts and the development of a child’s identity as a multilingual person. We identified at least three positive effects that extend beyond the classroom and are the results of beginning to study English from a younger age:

1. A positive disposition towards English and willingness to look for opportunities outside of class to practice it.

2. Ability to understand English in authentic communicative contexts.

3. Access to a greater range of sociocultural possibilities through English, for example on the internet.

The following excerpts exemplify each of these impacts:

1. Disposition: A mother described how today’s children have a “different chip” that allows them to use English without worrying about whether or not they will be able to understand:

M3. Si no, no sabes cuales son las instrucciones. Entonces, para ellas, como que tienen un chip diferente al mío. Por ejemplo, yo lo veo: o sea, que no sé cómo le entienden a las instrucciones del videojuego, aunque no saben el inglés perfecto; pero digo, no sé, pero ellas llegan a lo que necesitan por medio de… con pequeñas palabras que se saben, las frases le van pegando; no sé cómo le hacen, pero le buscan y le siguen al juego; pero bueno, ¡hasta eso se les facilita!

2. Ability: The following anecdote shows how from one mother’s point of view there is a clear and tangible result of her son studying English. She sees that he is able to understand native English speakers in a movie and proclaims “ahí está el resultado.”

Ent: ¿Cómo ha visto que las clases de inglés han impactado en que los niños aprendan nuevas cosas en… del idioma inglés?

EM: Pues simplemente cuando estamos viendo una película que no está traducida, ellos saben, de repente entienden algunas palabras, y eso es muy bueno, porque se queda uno sorprendido. Y ahí está el resultado.

3. Access: We found ample evidence that children were able to use their English to access information, and actively looked for opportunities to use their English. This went beyond even doing their homework or projects assigned by their teacher:

Ent:¿Ustedes tiene algún familiar en Estados Unidos? por ejemplo, ¿Algún contacto?

N: Yo en mi caso mi mamá y dos hermanos.

Ent: ¿Están en Estados Unidos?

N: Primos, sobrinos.

Ent: ¿Y hablan inglés?

N: [Afirma] De hecho mis hijos los tienen de contacto ahora que se usa el Facebook y pues es otra idea ¿no? [muletilla] Que ellos por ejemplo mis sobrinos sólo inglés, inglés todo inglés, igual y así Emiliano es lo que hace [pone al] traductor Google entonces de alguna manera… pues no, o sea es que ahorita hay un sin fin de herramientas.

Impact in the area of culture and the concept of interculturality

One of the research questions we asked relating to culture was how the PNIEB has contributed to students’ understanding of larger world (see research question 2.1 above). Our main finding here was that there have been positive results in the ways that the PNIEB contributes to students’ global vision, but that this is one area where there is enormous room for improvement. This is to say, the program is meeting its objective of exposing students to other cultures to a certain extent, but it is falling somewhat short. In particular, we found that the teachers do not conceptualize this objective as part of their overall purpose for teaching in the program, and most cannot clearly articulate what it means to expose children to other cultures through English class beyond a fairly superficial “food & festivities” approach (when asked about cultural aspects of their teaching, almost all pointed to Halloween as the example of inclusion of foreign cultures). To summarize:

1. PNIEB classes are including some cultural aspects in fulfillment of the program’s goals, but…

2. treatment of culture is quite superficial, and is mostly limited to festivals, and…

3. parents do not perceive any connection between their child’s English class and cultural elements.

We would suggest that the exploration of cultures in PNIEB cannot be deepened in order to “sacarle más jugo” from this aspect of the program, above all to extend the students’ vision of culture – in the anthropological sense – beyond just festivities.

One concept that we wanted to explore was interculturality, or the students’ ability to perceive the world through a different cultural lens. The methodology that we devised to explore the children’s perception of cultural differences was to give them a concrete and well-known example – the annual San Marcos festival in Aguascalientes – and have them talk about this event from the point of view of how a foreigner would experience. That is to say, we wanted to them to try to put themselves in someone else’s (cultural) shoes. The San Marcos scenario then required them to think about how they represent their own community and culture to an outsider. The following excerpt shows a typical interaction with the Feria de San Marcos scenario:

Ent: Imagínense que su escuela decidiera participar en apoyo en la feria de San Marcos, que solicitaran niños de las escuelas, y que su escuela participara, y los eligieran a ustedes para apoyar en la feria, porque van a venir niños de otro país, que hablan inglés y necesitan que otros niños los ayuden, ¿ustedes se animarían a participar?

Sandra: Sí.

Ent: ¿Sí Sandra?

Sandra: Que nos ayuden a nosotros y nosotros a ellos.

Ent: ¿Qué creen que les preguntarían?

Carlos: ¿Cómo te llamas?

Mayra: ¿Cómo nos llamamos?

Ent: Como se llaman…

Carlos: ¿Cuántos años tenemos?

Sandra: ¿Dónde viven?

Alumnos: [risas]

Ent: ¿Y sí les entenderían si les hablan en inglés?

Carlos: Pos el nombre si le entiendo cuando me preguntan a mí, mi nombre.

Miguel: My name is.

Carlos: Yes, my name is. […]

Ent: Y si vienen niños de otros países a la feria quizás quisieran saber algo sobre Aguascalientes, ¿Qué creen que les preguntarían? […]

Miguel: Cuales son las culturas y tradiciones

Ent: Culturas y tradiciones…

Carlos: ¿.Como viven?

Miguel: Artesanías que hacen.

Ent: ¿Y ustedes…?

Mayra: Que… qué se celebra.

Ent: ¿A qué… qué se celebra?

Mayra: Días festivos

Ent: Muy bien Mayra. ¿Y ustedes les preguntarían también eso mismo a los niños de otros países?

Alumnos en coro: ¡Sí!

The scenario elicits the students to adopt an intercultural perspective and imagine a situation that they have not actually experienced. A significant challenge for foreign language programs is that students generally have very few or no opportunities to interact with native speakers of the target language. However, although most children in Aguascalientes reported that they had never spoken directly with an angloparlante, their spontaneous answers to the San Marcos scenario revealed that most did not have difficulties imagining what it would be like to interact with foreigners:

Ent: ¿Qué creen que los niños les preguntarían a ustedes?

Ángel: Pues por ejemplo nos preguntarían qué lugares nos recomendarían a nosotros o qué, por ejemplo sí hay juegos para su edad, qué juegos y qué restaurantes para conocer mejor y saber en cuáles es preferible.

Farit: Yo para que conozcan la cultura mexicana y cuando vayan a su país la den a conocer ahí.

Verónica: Yo también les enseñaría a dónde se pueden hospedar, dónde son los mejores hoteles para quedarse aquí para que como dice Farid para que cuando lleguen allá les platiquen lo bueno que es aquí en México […] Yo creo que es bueno que los que viven aquí y vienen turistas de otro país le muestren Aguascalientes o no sé, dónde lleguen y creo que es bueno que también haya lugares donde te puedan mostrar los lugares más importantes de la ciudad.

Ent: Muy bien Verónica, y todas esas cosas que ustedes me dijeron que les gustaría platicarles a esos niños, ¿creen que se las podrían decir en inglés?

Verónica: Pues sí, con algo a veces trabados o así pero sí se las podríamos explicar.

The children impressed us with their ability to express their intercultural disposition, to articulate information that would be relevant to visitors, and their confidence to interact in English. As Verónica mentions above, it does not bother them if they are “a veces trabados” because they are confident they will be able to make themselves understood.

Ent: ¿Qué creen que les preguntarían los niños que vie... no hablan nada de español eh? ¿Qué creen que les preguntarían a ustedes? Quien sea… Darwin…

Darwin: Cuál es el lugar, dónde es el lugar más histórico, pero en inglés.

Ent: ¿Le entenderías Darwin?

Darwin: Sí, porque ya sé decir eso.

Ent: Jorge, ¿qué crees que les preguntarían?

Jorge: Yo creo que me preguntarían que qué cosas hay en Aguascalientes y todo eso. Y yo les diría que hay museos, tradiciones, el barrio de San Marcos, La Isla, Expoplaza, un buen de cosas.

Ent: Y tú podrías responderles cómo ir ahí?

Jorge: Yes!

Moni: Yo les preguntaría qué clase de actividades hacen en su vida diaria.

In the state capital, the children’s responses were consistent across schools of different socioeconomic levels. The children in rural areas tended to have more difficulty talking about the scene, likely because the situation of the Feria and imagining many foreign visitors was not as familiar, although they were still able to express some intercultural awareness.

The titular teachers affirmed that, according to their point of view, they have seen that the PNIEB promotes interaction with other cultures and even an acceptance of the mixing of cultures and ethnicities that is presented in the English texts and materials. They explained that they feel this is a positive effect that children see this intercultural and mixing as something “normal”:

Ent: ¿Ustedes creen que ese enfoque sociocultural de reconocer otras culturas se ha visto en la clase de inglés?

[Pausa prolongada, nadie responde]

Ent: ¿Hay alguna evidencia de eso?

MT1: ¿De la interculturalidad? […] Al momento en que ellos trabajan con diferentes palabras, los tecnicismos, el lenguaje, sus formas de representar las imágenes, pues existe ese intercambio de interculturalidad, ese respeto hacia las costumbres, por supuesto que sí se ve en la clase.

MT2: Y por ejemplo la vestimenta de uno a otro, cómo están vestidos, al momento de enseñar cómo se dice, cómo lo pueden decir ellos, pues sí si está empleando; incluso, les pasa videos donde no nada más salen niños blancos o morenitos, sino que mezclados, sino que no hacen un así… de raciocinio o racionalidad.

MT1: En cuanto a las razas, ¿verdad? El respeto, respeto a la equidad, la equidad de género, sí, sí, se aprecia.

Ent: Se observa…

MT1: A evitar la discriminación respecto a las culturas, sí se ve en la clase, por las imágenes que proyectan, porque ellos traen material donde presentan… hacen sus presentaciones en PowerPoint los docentes, […] ellos traen presentaciones, se apoyan con la tecnología los docentes.

RB. Y, ¿cómo lo ven los muchachos, los alumnos, es cosas de otro mundo?

MT2: No, no, es normal para ellos.

Impact in the area of connections

We were especially interested in identifying ways that studying English effects in other areas of students’ academic life (see research question 3.1 above). That is, we wanted to determine what sorts of beneficial effects the English program is having on the students’ general academic learning across the school curriculum.

The responses we obtained in the interviewed indicated that English can improve students’ learning in other subject areas. This is because students are capable of accessing similar academic information and content in two languages. The presentation of information by both teachers, in Spanish and English, exposes the student to the same content in different ways, reinforcing the themes by allowing the teacher to get additional feedback, sometimes clarifying topics that were initially seen in one language by reviewing them again in the other language. Both Spanish and English teachers recognized implicitly that “re-teaching” content in the other language could strengthen students’ learning process.

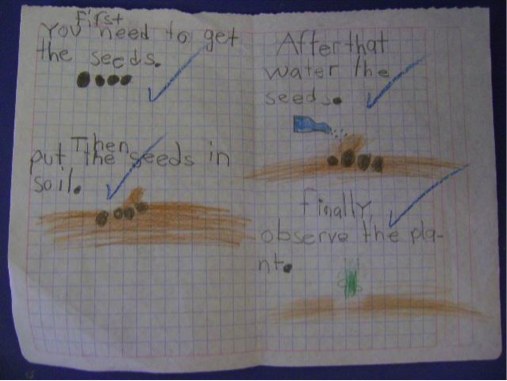

Here, we would recommend that teachers purposively align the contents of their teaching to make these intercurricular connections intentional rather than incidental. For example, a second grade classroom was studying the sequencing words in English: first, next, then, last. However, the content of the lesson was planting a seed and growing a plant (see Figure X). Clearly, this has connections with science, and can reinforce the student’s understanding of the life cycle of a plant. However, the science content of the lesson was secondary to the linguistic content of the words used in English to order events. We suggest that the science content be foregrounded and explicitly connected to what students have seen in Spanish. This approach is referred to as content-based instruction (CBI, Richards and Rodgers, 2001), or content-language integrated learning (CLIL) (Wannagat, 2007).

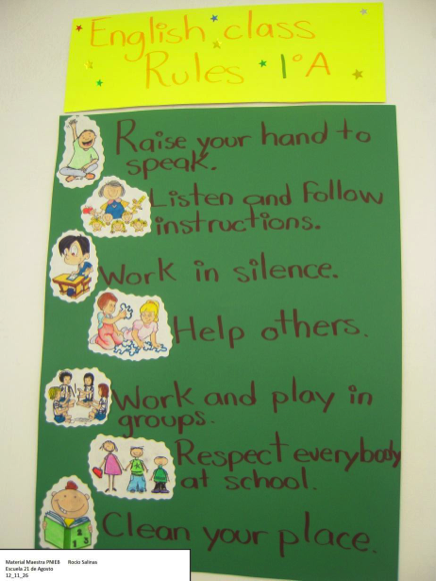

For example, when studying literature and narratives in Spanish children learn about the basic story elements: setting, characters, plot, and so forth. Stories in English have these same elements, and teachers should be encouraged to draw on students’ background knowledge to help them see these connections, and reinforce through English what has been learned in Spanish. Similarly, Figure 1 shows how for a kindergarten class the rules in English can help reinforce the classroom socialization process for young children just entering school. In this way, students are acquiring English, and simultaneously English lessons serve as a medium for learning in other areas.

Figure 2: Connection with English and science class

Figure 3: Connection with English and values and rules

Another cross-curricular connection that is of particular interest for the PNIEB is the question of the effect of early foreign language learning for literacy acquisition. In this study, we were interested in detecting how exposure to English literacy might affect their development of reading and writing in Spanish, especially for children in grades K-2 (ages 4 to 6). The early acquisition literacy in two languages is referred to as biliteracy development.

A concern of some parents and teachers is that early exposure to literacy in a second language, before the reading and writing in the first language has been fully mastered, may lead to confusion and delay or hinder the child’s development of phonemic awareness, a key early stage in learning to read. Because the phonology and spelling of English is different, children may temporarily have some problems distinguishing between the two writing systems. However, this study indicates that most teachers find that the opposite is true: exposure to reading and writing in the foreign language actually helps young students learn to read and write in their first language. This may be because early L2 literacy contributes to an awareness of how language works in general, and this awareness helps the student become a stronger reader and writer. Certainly, the question of biliteracy development and early foreign language learning warrants further empirical research.

Conclusion

This article reports on some of the results from a study done of the PNIEB in the state of Aguascalientes. Certainly, the PNIEB program allows students in public schools in Mexico an unprecedented opportunity to develop communicative competence in English, which will serve them well in their future studies and careers. However, in this paper we have especially highlighted the other, non-linguistic benefits of early foreign language learning. We have shown how learning English from a young age does not just benefit students in terms of acquiring vocabulary, grammar, and language skills; it also benefits them in other ways, both academically and socially.

In terms of academics, we have shown that the English program has positive effects in other subject areas. English is a language that can serve as a medium for learning in any other area, and therefore has many possibilities for intercurricular connections. In terms of social connections, we showed how students are motivated to expand their English use beyond the classroom and school, and take the initiative to use English in their daily lives in multiple creative ways. Finally, the PNIEB also fulfills a function of putting students in contact with other cultures and giving them a more global or cosmopolitan vision. However, here we noted that the PNIEB has more potential for teachers to deepen and develop the cultural content of their lessons.

Acknowledgments

The authors were co-principal investigators of this study, which was part of a larger study commissioned by the Ministry of Education of the State of Aguascalientes. The authors would like to thank the ministry, the coordinators of the PNIEB in Aguascalientes, as well as our research team: Magdalena López de Anda (project manager), Miguel Cedeño, Ana Maria Navarro, and the transcription team at ITESO.

References

Ali, N. L., Hamid, M. O., & Moni, K. (2011). English in primary education in Malaysia: Policies, outcomes and stakeholders' lived experiences. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(2), 147-166.

American Council of ForeignLanguage Teachers (ACTFL). (1996). Standards for Foreign Language Learning: Preparing for the 21st, 3rd Ed. Alexandria, VA: Allen Press.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

Enever, J. & Moon, J. (2010). A global revolution? Teaching English at primary school. London, UK: British Council.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine.

Hamid, M. O. (2010). Globalisation, English for everyone and English teacher capacity: Language policy discourses and realities in Bangladesh. Current Issues in Language Planning, 11(4), 289-310.

Herazo, R. J. D., Rodríguez, S. J., & Arellano, D. L. (2012). Opportunity and incentive for becoming bilingual in Colombia: Implications for Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo. Íkala: Revista de lenguaje y cultura, 17(2), 199-213.

Hesse-Biber, S.N., & Leavy, P. (2011). The Practice of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hoa, T. M., & Tuan, Q. (2007). Teaching English in primary schools in Vietnam: An overview. Current Issues in Language Planning , 8 (2), 162-173.

King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Matear, A. (2008). English language learning and education policy in Chile: Can English really open doors for all? Asia Pacific Journal of Education , 28 (2), 131-147.

Nguyen, H. T. M. (2011). Primary English language education policy in Vietnam: Insights from implementation. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(2), 225-249.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pennycook, A. (2007). The myth of English as an international language. In S. Makoni and A. Pennycook (Eds.),Disinventing and reconstituting languages, (pp. 90-115). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Sayer, P. (forthcoming-2014). Expanding global language education in public primary schools: The national English program in Mexico. In T. Ricento (Ed.), Global English and language policies: Transnational perspectives. New York: Springer.

Secretaria de Educación Pública. (2010). Fundamentos Curriculares del PNIEB. México, DF: SEP.

Tollefson, J. (2000). Policy and ideology in the spread of English. In The sociopolitics of English language teaching, eds. J. K. Hall and W. Eggington, 7-21. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Vargas, R., & Ban, R. (2011). Paso a paso con el PNIEB en las aulas [Step by step with the PNIEB in the classroom]. Melbourne, FL: Latin American Educational Services

Wannagat, U. (2007). Learning through L2 – content and language integrated learning (CLIL) and English as medium of instruction (EMI). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5): 663-682.

Woodgate-Jones, A. (2009). The educational aims of primary MFL teaching: An investigation into the perceived importance of linguistic competence and intercultural understanding. The Language Learning Journal, 37(2), 255-265.

Zappa-Hollman, S. (2007). EFL in Argentina's schools: Teachers' perspectives on policy changes and instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 618-625.

[1] Although a full consideration of how social practices and competencies are defined and articulated in the PNIEB is beyond the scope of this paper, see Vargas and Ban (2011) for a fuller explanation of the theoretical underpinnings of the sociocultural curriculum of the PNIEB.

[2] Although many scholars with a critical perspective have questioned this presumption; see, for example, Tollefson (2000), and Pennycook’s (2007) critique of the “myth of international English.”