Introduction

In an increasingly connected world, the learning of foreign languages has become a prevalent need. Nowadays, the job market is more complex than it was some years ago; therefore, it demands highly educated and trained workers. Being able to communicate effectively, to comprehend and express oneself in other languages are some of the necessary skills in today’s globalized world. English has become the most useful language for international communication and the lingua franca in fields such as marketing, international commerce and tourism (Bassi & Álvarez, 2014). However, it is now assumed that the majority of professionals must be able to communicate in English. In fact, being bilingual is not anything new. If one wants to succeed in any profession, it is advisable to know more than two languages. Due to this demand, the number of language schools worldwide has increased significantly in the last years.

Various service companies that have been established in Costa Rica through time now require professionals with different language skills. Hence, numerous schools in the country provide people with the opportunity to learn these languages. In addition, since Costa Rica is considered a popular tourist destination, many foreigners choose this country to learn Spanish. That is why there are more than seventy language schools offering Spanish classes in Costa Rica. Similarly, the places for learning English are numerous, and the academies where other foreign languages, such as Portuguese, French, and Italian are taught, have multiplied considerably in the recent years.

In these private schools, the requirements for hiring teachers vary significantly. In some of them, either a university degree in education or a certification in language teaching might be needed; in others, the only condition is to be a native speaker of the language being taught. This occurs because of the strong belief that a native speaker is the ideal language teacher, even without the necessary credentials. Administrators in some schools, not only in Costa Rica, but also in other countries, will not hire non-native speaking teachers of a language because of their non-native status, regardless of the education and experience they have. As an illustration, Illés (1991, cited in Medgyes, 2001) states that the principal of a language school in London sent a letter of rejection to a non-native English speaking teacher who wanted to work there, with the following: “I am afraid we have to insist that all our teachers are native speakers of English. Our students do not travel halfway round the world only to be taught by a non-native speaker (however good that person’s English may be)” (p. 432). It becomes important, therefore, to find out why this occurs and who supports this assumption: the administrators, the students, the teachers themselves or all of them.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the perceptions of a number of schools in Costa Rica towards non-native speaking teachers of Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, and Italian. Besides finding out what teachers, program administrators and students think of non-native speaking teachers, this research presents valuable information for the need of equal treatment in the language teaching field. This, in turn, will create awareness concerning this relevant issue.

Literature Review

The Importance of Language Learning

Due to globalization, language learning has become a priority worldwide. Regardless of the field of study, most professionals should be able to communicate in at least two or three languages if they wish to be highly competitive. Moreover, cultural sensitivity is greatly valued in any profession, and learning another language implies getting to know and understand a different culture.

In the case of Spanish, there are several reasons why speaking this language is really beneficial nowadays. According to the don Quijote Spanish language school website (2011), these are some important global statistics of Spanish speakers:

-Spanish is the world’s third most spoken language, after Mandarin Chinese and English, and ranks second in terms of native speakers.

-At the end of the 19th century, 60 million people spoke Spanish. Today, almost 500 million people worldwide speak Spanish!

-Spanish is the mother tongue of approximately 388 million people in 21 countries.

-Spanish is the second most used language in international communication.

-The US Census Bureau reports that the nation’s Hispanic population is expected to jump to 49.3 million from 38.2 million by 2015. The 39 million Hispanics currently living in the USA make up 12.5% of the total population.

There is little doubt that the Spanish language has proved to be one of the most necessary and important languages to be learned in the future. Therefore, the number of schools in Spain and Latin America dedicated to teaching Spanish has increased considerably in the last few years. In Costa Rica, there are almost one hundred institutes where foreigners can learn this language. In general, the Costa Rican Spanish language schools offer the opportunity to learn or improve Spanish skills in small groups, while experiencing the country’s culture. In addition, students usually take part in extracurricular activities such as tours, cooking classes, and dance lessons. INTENSA, Intercultura and the Centro Panamericano de Idiomas (CPI) are just three of the many private Spanish schools.

Communicating in English represented an advantage some years ago. Now it is a worldwide need. The website English Language (2014) lists the following facts as some important statistics of this language:

-English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language.

-Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers, but not in distribution by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese.

-Over 700 million people speak English as a foreign language.

-More than half of the world’s technical and scientific periodicals are in English.

-The main language used throughout the world on the internet is English.

Since it is vital to learn English today, Costa Rica offers an extensive variety of institutes where people can do so. Some of the most popular ones are the Centro Cultural Costarricense Norteamericano (CCCN), INTENSA and Intercultura. These and other schools have campuses in different regions of the country, allowing students the opportunity to study English in both urban and rural places.

Due to the recent expansion of multinational companies, being proficient in languages other than English has become necessary. Because of this, the interest in learning languages, such as Portuguese, French and Italian, has increased lately. The AmeriSpan Study Abroad (2011) website includes the following information about Portuguese:

Portuguese has been ranked as the fifth most spoken language in the world with about 272.9 million native speakers, most of which reside in Brazil and Portugal. Learning Portuguese can open doors to employment in a variety of areas.

In addition, Shryok (2009) mentions some relevant facts about French:

-French as a foreign language is the second most frequently taught language in the world after English.

-28 countries have French as an official language.

-French is the only language other than English spoken on five continents.

-More tourists visit France than any other country in the world.

-The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language 2008 Survey indicates that more students are interested in studying French than any other foreign language in the United States.

Some statistics of the Italian language, stated by the Italian Language website (2011), are the following:

-Italian is spoken by over 80 million people in Italy and other places of the world such as Malta, San Marino and parts of Switzerland, Croatia, Slovenia and France.

-Italy is one of the biggest places for tourism, being the fifth most visited country in the world.

-Italian is the fifth most taught non-native language, after English, French, Spanish and German.

There are internationally known institutes for learning Portuguese, French, and Italian in Costa Rica, such as: Fundación de Cultura, Difusión y Estudios Brasileiros (FCDEB), the Alianza Cultural Franco-Costarricense (AF) and the Asociación Cultural Dante Alighieri (DA). Even though these schools are the ones most people prefer in order to learn these languages, other academies offer classes as well.

These schools offering Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, and Italian instruction have their own regulations and requirements in terms of hiring language teachers. Some of them accept both native and non-native speakers of those languages. Others do not hire non-native speakers, even if they hold the necessary teaching degrees or certifications, because it is an institutional policy or because the students are the ones who request native speakers. This fact supports the notion that the ideal teacher is a native speaker for these institutions.

The Native Speaker Fallacy

Teachers of all languages are either native or non-native; nevertheless, how is this nativeness determined? The most common answer would be by the country where a person was born. Thus, a native speaker of English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, or Italian is a person who is born in an English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, or Italian-speaking country, respectively. Nonetheless, if a child has bilingual parents who might not share the same mother tongue, he or she will learn to speak two different languages at the same time. Also, if a person was born in a particular country and then moves to another one where a distinct language is spoken, he or she will acquire that other language as well. These circumstances go beyond the common belief of what constitutes a native speaker since they show that one can grow up being a native speaker of more than one language.

The native speaker fallacy refers to the belief that the best language teacher is a native speaker of that language. Phillipson (1992) created the term, and was opposed to the NS fallacy. He believed that teachers are made rather than born whether teachers are native or non-native (Fathelbab, 2011, p. 1). Non-native speakers, however, sometimes experience discrimination in the job market because they are not considered as good as native speakers. What is even worse is that, in some cases, even if non-native speakers hold the required credentials to teach the language and native speakers do not, the last ones might be preferred. Selvi (2010) mentions the following:

…native speakers are believed to be equipped with a genetically endowed capacity to teach the language; whereas non-native speakers are perceived as deficient imitators of the language they are trying to learn. (p. 174)

This refers to the results of a study which documented that native speakerism was more important than relevant education background and sufficient teaching experience. Selvi (2010) continues to question this idea with the following:

What might be the rationale behind assuming that a student who graduates as a marine biologist, petroleum engineer, or software developer can successfully meet the expectations of the students in a classroom in rural Thailand, metropolitan Tokyo, or suburban Beijing, only as a result of a few weeks of training, provided that he or she is a native speaker of English? (p. 174)

Since English is spoken as a foreign language by more people than as a second language, most English teachers are non-native speakers. Even so, native speakers seem to have a clear advantage over the first ones.

Native English speakers without teaching qualifications are more likely to be hired as ESL teachers than qualified and experienced NNESTs [non-native English speaker teachers], especially outside the United States. But many in the profession argue that teaching credentials should be required of all English teachers, regardless of their native language. This would shift the emphasis in hiring from who the job candidates are (i.e., native or nonnative speakers of English) to what they are (i.e., qualified English teachers) and allow for more democratic employment practices. (Maum, 2002, p.1)

The assumption that native speakers are better language teachers than non-native speakers is a common myth in the teaching-learning field in spite of the language. There is a general misconception that anybody can become a language teacher as long as he or she is a native speaker, even if this person does not have the required degree or certification. However, it is not fair for a proficient, prepared and experienced non-native teacher to be rejected because a qualified or unqualified native speaker is believed to do a better job.

Population of the Study and Method

In order to find out the perceptions towards native and non-native language teachers, a questionnaire was designed by the researcher and was carried out in 2011 (see Appendices A, B, C). The academic coordinators (7) of the language programs (English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Italian), teachers (58) and students (207) completed the questionnaires. The total number of participants was 272. They came from seven different schools in Costa Rica: INTENSA, Intercultura, Centro Panamericano de Idiomas (CPI), Instituto San Joaquín de Flores, Alianza Cultural Franco-Costarricense (AF),Fundación de Cultura, Difusión y Estudios Brasileiros (FCDEB) and the Asociación Cultural Dante Alighieri (DA). The academic coordinators of the language schools were interviewed in order to know how hiring was carried out, what they think about non-native speaking teachers, the number of teachers there, etc.

Results

In this section I will provide the data gathered from the questionnaires and interviews. By interviewing the coordinators of the language schools, it was found out that the requirements for hiring language teachers vary. In one it is an institutional policy to hire only native speakers; they should hold a university degree although not necessarily related to language teaching. They do, however, need to have a language certification because the school does not provide any teacher training. In another institute, the students are the ones who request native speakers as teachers, especially for individual classes and intermediate-advanced levels. Lastly, another school requires that the teaching staff be 50% native speakers and 50% non-native speakers. The following table shows the distribution of the teachers working in these schools based on their nativeness.

Table 1. Distribution of Language Teachers: Native Speakers or Non-native Speakers

When asked how necessary it is for a language teacher to be a native speaker, 57% of the coordinators, 48% of the teachers and 43% of the students responded it is very necessary. For the students 34% believe it is somewhat significant. Some of the reasons are: “Because I can teach the correct accent and it is important for a teacher not to make mistakes as the students”, and “Native speakers are experts in their mother tongues, so we will learn the correct forms.” Most answers made reference to perfect pronunciation, informal language and cultural knowledge. Also, several mentioned the native speaker fallacy: “Because they have the belief that with a native teacher they will learn better” and “Because they think that a non-native teacher does not know the language well.”

In contrast, others responded that non-native speakers can also be good language teachers. The following are excerpts:

There are non-native teachers who can be more qualified and have more experience than a native! The fact that we are French does not mean we know how to teach.

Because if he [the teacher] really knows English, his nationality does not matter.

In Belgium I went to school. There I learned French from a non-native teacher and she was really good. My French is excellent.

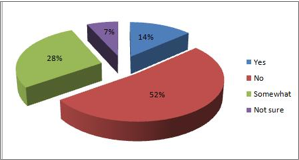

As it could be seen, there are a variety of opinions in terms concerning how native speaking teachers and non-native speaking teachers are perceived. The following graph illustrates this information:

Graph 1. Need for a Language Teacher to Be a NS

In addition, coordinators and teachers were asked about students’ preference for a language teacher: a native or a non-native speaker. Concerning the coordinators, 88% think that students prefer a native speaker teacher while 64% of the teachers replied students usually prefer a native speaker. Indeed, 62% of the students would rather have a native teacher because: “They have more confidence”; “The class seems more real”; and “I prefer to learn from the best.”

The ones without a preference mentioned: “It depends on how they teach rather than where they are from,” and those who believe it depends on the skills and levels taught explained that non-native speakers are preferred to teach grammar and beginners, while native speakers are favored to teach advanced levels, oral expression and culture.

Selvi (2010) affirms that program administrators in the ELT profession unfortunately often accept the native speaker fallacy and believe that there is a notable difference between NTs and NNTs. Selvi mentions that while native speakers are considered the ideal teachers, non-native speakers are seen as less instructionally qualified and less linguistically competent than native speaking teachers.

As it can be seen in the graph, the highest percentage for students, teachers and administrators shows the existence of the native speaker fallacy in these language schools.

Graph 2. Preference for a Language Teacher: Students, Teachers and Administrators

The participants were also asked if they agreed with the fact that all, most, or several (depending on the institute) of the language teachers in the schools were native speakers. Most administrators (57%), teachers (77%) and students (82%) showed their favorable opinion towards this. As to why they think this way, they said it gives the schools more credibility, authenticity, better quality and a status of seriousness as an institution. Moreover, students indicated the importance of being exposed to different accents and cultures.

The next graph shows how most teachers, students, and administrators agree with having native speakers working in the institutes.

Graph 3. Agreement of the Number of NSs in School

In terms of holding certifications, 50% of the administrators disagree with teachers not being qualified and 33% agree. 51% of the teachers believe it is fine for educators not to have any type of preparation and 25% agree with it to some extent. Concerning the students, 40% accept this fact and 30% do not. There were many insights regarding this. Some accept this situation: “There are degrees which only give theoretical knowledge, not practical. Somebody without a degree but who has taught for many years can be a very good teacher”; “It is possible to teach a language without having a teaching degree, as long as one does it with goodwill and responsibility”; and “Anyone who knows English can teach it.” On the other hand, others believe having teaching credentials is essential: “It is necessary to learn how to teach”; “For the same reason I would not like an unqualified doctor to take care of me. Teaching is something one learns”; “I think it is fine but it is not fair for those who actually went to school for teaching.” The distribution of the percentages regarding this issue is illustrated in the next graph.

Graph 4. Agreement with Unqualified Language Teachers

In terms of having Costa Rican teachers, 52% of the students expressed they would not mind: “As long as they are well-prepared professors. I think they can teach the language well” and “The truth is that just as there are good native teachers of English, why couldn’t a Costa Rican teach like them? There are good professors here.” On the contrary, 28% of the students said that they would mind having a Costa Rican teacher because: “The accent can interfere”; “I do not think it would be the same quality”; “I would not be sure of the teacher’s language command”; and “I think a native is the ideal teacher.” The graph below illustrates the different percentages.

Graph 5. Would Students Mind Having Costa Rican Teachers?

Interestingly, research has shown that when teachers share their students’ native language, it can be beneficial. Maum (2002) states the following in reference to this:

Many NNESTs [non-native English speaker teachers], especially those who have the same first language as their students, have developed a keen awareness of the differences between English and their students’ mother tongue. This sensitivity gives them the ability to anticipate their students’ linguistic problems. (p. 1)

In addition, coordinators were asked to choose one of the following to hire as a possible language teacher: a native speaker without any teaching certification or experience, or a non-native speaker with teaching certification and experience. All of them except one would prefer the qualified non-native speaker, which represented 86%. Some of their reasons were: “In order to teach a language it is essential and necessary to know about pedagogy, evaluation and to have full command of the grammatical rules”; “The native speaker with training is the ideal one”; and “Probably I would not hire any of them, but if I had to choose one, I would give the job to the non-native speaker if the teacher could speak English like a native speaker.” This information can be appreciated in the following graph.

Graph 6. Preferences for a NS or NNS in Relation to Experience and Qualification

As a way to view the number of native and non-native speaking teachers and their qualifications, the following graph shows this information. Out of the 58 teachers who completed the questionnaire, 39 of them are native speakers of the languages they teach, representing 67%. Meanwhile, 19 teachers are non-native speakers, which correspond to 33%.

Graph 7 Number of NTs and NNTs

Regarding the educators’ academic preparation, 59% of the native speakers hold a language teaching degree or certification, while 41% do not. Meanwhile, 53% of the non-native speakers do not hold the necessary teaching credentials and 47% do. It is interesting to see that even non-native speaking teachers without qualifications are hired. However, the situations vary from teachers who know the language but do not possess a teaching degree, to those who lived abroad and acquired the language naturally. Graph 8 shows the percentages:

Graph 8 Language Teaching Degree or Certification

Conclusions

Although some research regarding native/non-native speaking teachers has been carried out recently, the largest part of the literature focuses on the teaching of the English language, especially in ESL contexts. This is explained by Moussu and Llurda (2008) in the following:

…we have often wondered about the teaching of other languages and noticed that very little has been done to investigate how non-native teachers of languages other than English are perceived by their students and supervisors. (p. 342)

Consequently, research on how non-native teachers in Costa Rican language schools are considered by academic coordinators, students and themselves is of valuable contribution.

The native/non-native speaker issue, whereas essential in language learning, is frequently not seen as a prevalent matter in a Foreign Language (FL) context such as Costa Rica. Program administrators, teachers and students are many times not aware of what it means to be a native or non-native speaking teacher or the strengths and weaknesses of each. Besides, there is a strong belief that having native speakers as language teachers is the best policy; many people consider this myth as an absolute truth. This is probably due to the propaganda of many private institutes as well as their sometimes unfair hiring practices.

The results in this research reflect the existence of the native speaker fallacy in several language schools of the country, from coordinators, teachers and students. Something surprising, however, is that most students would not mind having Costa Rican teachers of those languages, besides Spanish. This seems to contradict the native speaker fallacy since some students accept Costa Rican teachers, but would prefer to have a native speaker teaching them. In addition, non-native English teachers seem to be more present in language schools due to the expansion of this language and the need for more teachers specialized in this area. It may also have to do with the fact that English is taught as a foreign language. On the other hand, all Spanish teachers appear to be native speakers, mostly Costa Rican, because that is what foreign students look for, or at least that is what the language schools usually assume since Spanish is taught as a second language in this country. In the case of the other languages, native speakers prevail, with a few exceptions. The reason for this could be that despite being foreign languages, there are fewer certified teachers, at least in Portuguese and Italian. This might promote the misconception that native speakers of those languages are the ideal teachers.

The native/non-native speaker notion is a controversial but an indispensable concern in language teaching. Thus, it becomes crucial to create awareness regarding this issue in language professionals as well as in students. It is important then, to continue carrying out research in different languages, especially those that are becoming more popular. Investigating the perceptions towards native teachers and non-native teachers at the university level, in Costa Rica and in other countries, would be of great value. As the number of language teachers increases day by day all around the globe, so does the urge to become more knowledgeable on this matter.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the academic coordinators, teachers and students at Intercultura (Heredia), Centro Panamericano de Idiomas/English Program (San Joaquín de Flores), Instituto San Joaquín de Flores, Dante Alighieri (Heredia and San Pedro), Alianza Francesa (San José), INTENSA (Heredia), Fundación de Cultura, and Difusión y Estudios Brasileños (Santa Ana) for their time and help in completing the questionnaires.

References

--, English language statistics. English Language: All about the English Language. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www.englishlanguageguide.com/facts/stats

--, Italian language statistics. Italian Language: All about the Italian Language. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www.italianlanguageguide.com/facts/stats

--, Why learning Portuguese is important. (2011). AmeriSpan: The bridge between cultures. Retrieved July 17, 2011 from: http://study-portuguese.amerispan.com/why-learning-portuguese-is-important

--, Why study Spanish?(2011). donQuijote Spanish Language Learning. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www.donquijote.org/english/whyspanish.asp

Bassi, M. , & Álvarez, H. (2014). Habilidades para el siglo XXI: La enseñanza del inglés en Costa Rica. BID: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www.iadb.org/es/temas/educacion/habilidades-para-el-siglo-xxi-la-ensenanza-del-ingles-en-costa-rica,6641.html

Fathelbab, H. (2011) NESTs (Native English Speaking Teachers) & NNESTs (Non-Native English Speaking Teachers): Competence or Nativeness? AUC TESOL JOURNAL, Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www3.aucegypt.edu/auctesol/Default.aspx?issueid=8b20d438-2b85-4462-9f25-9be82e3c63dc&aid=02a23d44-6b7a-4054-bed2-78cb8b6c3317

Maum, R. (Dec. 2002). Nonnative-English-speaking teachers in the English teaching profession. Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/0209maum.html

Medgyes, P. (2001). When the teacher is a non-native speaker. In Marianne Celce-Murcia (Ed.). Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language. 3rd Edition. 429-442.

Moussu, L., & Llurda, E. (2008). Non-native English-speaking English language teachers: History and research. Language Teaching, 41(3), 315-348. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/al/research/groups/ellta/elted/events/download.pdf

Selvi, A. (2010). All Teachers Are Equal, but Some Teachers Are More Equal than Others: Trend Analysis of Job Advertisements in English Language Teaching. WATESOL NNEST Caucus Annual Review, 1, 156-180. Retrieved April 22, 2014 from: https://sites.google.com/site/watesolnnestcaucus/caucus-annual-review