During the summer of 2008, the most prominent features of the Integral Upper Secondary Education Reform in Mexico (Reforma Integral de Educación Medio Superior, RIEMS) were disseminated to secondary teachers through several forums on “competency”. These forums were aimed, in particular, at those belonging to the General Department of Industrial and Technological Education (Dirección General de Educación Tecnológica Industrial, DGETI) subsystem. Competency-based Education represents a new paradigm (Tobón, et al., 2010) used to approach all of the subjects in the upper secondary school curricula (and at every school level in the Mexican Educational system) trying to leave behind the traditional knowledge-based teaching and learning methodology. Formal training for using this approach was urgently needed, but unfortunately, was not provided probably due to the lack of a specific methodology (Díaz, 2006; Espinoza, et al., 2008; Zavala & Arnau, 2007). By means of consensus reached among different academic circles (e.g., the National Network for the Upper Secondary System from the Mexican Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions /Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior, ANUIES and regional academic authorities), specific competencies were selected for inclusion in the new program. These were then deconstructed into sub-skills, sub-capacities and specific knowledge called “attributes”. The competencies-based educational approach adopted by the Subsecretary of Upper Secondary Education (Subsecretaría de Educación Media Superior, SEMS) plans to address actual and current challenges with the intention of carrying out the whole learning experience using discipline-specific knowledge (Tobón, et al., 2010).

Educational competencies in the classroom

At the upper secondary level, students are expected to develop three kinds of competencies: generic, disciplinary and professional (SEMS, 2009). The first two are the foundation of the National Baccalaureate System(Sistema Nacional de Bachillerato/SNB) as they are present in every subsystem’s curriculum suchas Dirección General de Educación Tecnológica Agropecuaria/DGETA, Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicas/CECyTEs, Dirección General de Educación en Ciencia y Tecnología del Mar/DGECyTM. These competencies are of particular interest for standardized subjects such as English because both guide the new implementation of subject content. Therefore, they should be reflected in the planning of didactic strategies called “didactic sequences” because developing a competency takes more than one session. Such development could even take the entire course (Tobón, et al., 2010).

Trying to develop disciplinary competencies (in this case, communication skills) and generic competencies (personal) means that teachers must plan educational activities solving and address real problems and challenges in their students’ current context. Consequently, priority must be given to cultivate the next competencies and their attributes (SEMS, 2009). This means that the student:

1. knows him/herself and values him/herself and confronts challenges and problems taking into account the aims he/she follows;

2. is sensitive to art and participates in the appreciation and interpretation of its expressions in different genres;

3. chooses and practices healthy life styles;

4. listens to, interprets and emits pertinent messages in different contexts using appropriate means, codes and tools;

5. develops innovations and proposes solutions to problems based upon known methods;

6. holds a personal position about general interest themes, considering other points of view critically and reflexively;

7. learns autonomously during his/ her life;

8. participates and works collaboratively in an effective way in different teams;

9. participates with civic and ethic consciousness in the life of his/her community, region, Mexico and the world;

10. holds a respectful attitude towards differences between cultures, beliefs, values, ideas and social practices; and

11. contributes to sustainable development in an informed way with responsible actions. (pp. 6-14, author’s translation)

In the current National English Curriculum (SEMS, 2009), besides introducing both disciplinary and generic competencies, it is suggested that specific assessment rubrics be taken into account. Among those suggested are the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages Learning, Teaching and Assessment (CEFR) and the Canadian Benchmark which serve as a reference to assess students’ outcomes. A third consideration is the consolidation of a grammar oriented syllabus which was basis of the curriculum of English before the RIEMS. This syllabus progresses linearly from the verb “to be” in first semester to the “third conditional” structure in the fourth semester, leaving the fifth and sixth semesters to review and practice these structures in developing reading skills.

The competencies-based approach does not specify a specific methodology to achieve these goals. Teachers are free to develop their own approach using any information sources at their disposal. In some ways, however, all these sources can appear to collide and minimize each other making them difficult to apply in practice. This is even truer if we take into account the reality that teachers have only three hours a week to manage the entire teaching-learning process.

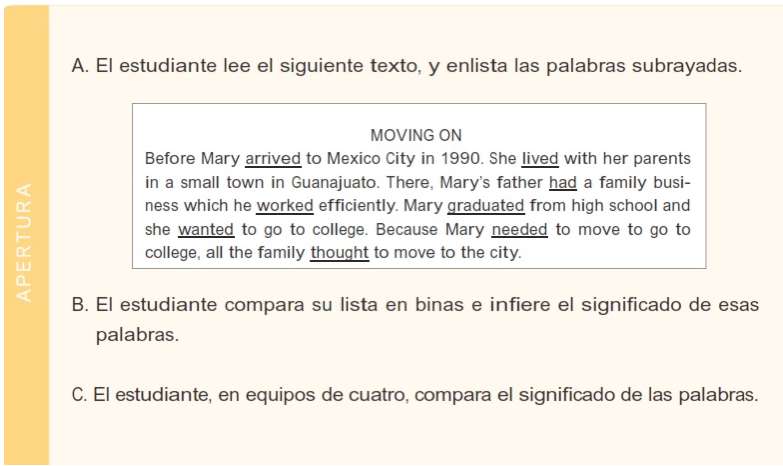

New ways to approach the English class are being urgently demanded because otherwise competency-based teaching and learning will end up becoming a simplified form of stating the same objectives and goals which could direct simple activities, such as those suggested below (Programa de Estudios-Inglés, SEMS, 2009):

Another main criticism of the way the Competency-Based Approach has been implemented in the SNB is that as there are still a number of teachers who have not received language teaching education lack a sufficient command of English to implement the new requirements (Ban, 2009; Mendez, 2007; Richards, 2009). Within the Mexican public system, this means that specialized training is essential. Another factor making implementation of the program difficult is the large classes, ranging from 45 to 60 students. Operation of a program, which develops an individual’s skills, attitudes and knowledge, while providing somewhat personalized instruction, is elusive under such conditions.

The goal of enabling individuals to express themselves by different means and through different contexts, (i.e., language competence) has been addressed in multiple discussions in Second Language Teaching and Learning Theory (Canale & Swain, 1980; Celce-Murcia, et al., 1995; Chomsky, 1965; Cummins, 1979; Hedge, 2000; Hymes, 1972). Hedge (2000) proposed that in order to be proficient in a language, learners are expected to develop the following competencies: linguistic, pragmatic, discourse and strategic, and fluency. Competency-based education originated in vocational training programs (Díaz, 2006; Richards, 2009; Richards & Rodgers, 2001) where it is possible to isolate necessary and straightforward activities to perform a specific task (e.g., to change a tire or to measure blood pressure). Developing specific skills to develop communicative competence (Hedge, 2000; Hymes, 1972), on the other hand, is a far more complex problem that seems, for many seems to have become an unrealized goal inside this new National English Curriculum.

Preparing teachers for the new curriculum

My view concerning the theory underlying generic and disciplinary competencies postulated by SEMS, however, is exactly the opposite. The goal is to develop an integrated individual and not just a Basic English learner. In my view, the most urgent need is to provide training courses for teachers which facilitate the use of educational strategies to implement this new approach for Mexican SNB’s teachers. Such courses might include: The participatory approach (Larsen Freeman, 2000), learning strategy training (Chamot, 2004, Larsen-Freeman, 2000; Rubin 1975), problem-based learning (Hearn & Hopper, 2008), sheltered English instruction (Moore & Sayer, 2009) and cooperative learning (Larsen-Freeman, 2000). These approaches could provide useful information in the consideration of the development of some generic competencies when learning an additional language.

Having in mind that “competencies” is an approach to implement in all subjects, discussions by educational theorists about the best way to implement this competency-based approach in Mexico o point out two ways this might be done (Díaz, 2006; Tobón, et al., 2010). The first is a full-frontal approach with the development of some competencies as the main goal in which the subject content is acquired as a consequence or almost incidentally. The second is a mixed approach in which teachers demonstrate the importance of subject content along with the development of the individual through tasks directed at the application of the competencies. In any case, the foundation of both relies on actual problems which need to be solved. Therefore, both approaches are certainly student- and situation- centered. In my opinion, a single textbook is unlikely to be designed which can address the multiple and complex realities of Mexico.

For all these reasons, I strongly suggest basing teaching and learning English on authentic materials as they make it possible to integrate all these considerations inside the SNB. Such materials can be even provided by our very own students using popular browsers such as Google, Yahoo, YouTube or Bing. If students have access to these resources, it may increase the opportunities to develop their autonomy. Other materials need to be supplied by the teacher, but these could be found inexpensively. Some specific suggestions are: songs (lyrics translated for beginners); musical videos (lyrics with subtitles for beginners); movies trailers (with subtitles in Spanish for beginners, in English for intermediate and advanced); popular sitcoms (with subtitles in Spanish and English); airline magazines (which usually present texts in two different languages); work out videos or DVDs; cooking recipes with pictures or in DVD format; brochures and booklets of popular tourist places or local attractions; manuals of electronic devices with diagrams and pictures, to name a few.

How authentic materials can help to achieve SNB’s competencies

Using authentic materials allows the development of many of the generic competencies proposed by the SNB. For example, songs, poems, manuals, sitcoms and movies provide vocabulary and lexical phrases in context. Students can use thinking skills by deducing, comparing, analyzing, critiquing and producing similar language. Songs, sitcoms and movies provide also a phonetic guide useful in oral and listening tasks. In Mexico, opportunities to be exposed to English may be scarce. English teachers must encourage students to learn from resources already available, thus developing autonomous learners and extending learning beyond the classroom. Authentic materials also allow the use of personal background knowledge, feelings, and thoughts which can be a framework to understand sociocultural differences between people. If we encourage our students to use available materials as a pattern, they can replicate such patterns with new technologies and/or with local resources. We also encourage the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), team work, and sustainability in our students’ curriculum.

Having in mind an actual problem, the main idea is that students learn vocabulary and grammar which they can transfer later when facing a familiar situation. For example, a student concerned about proper nutrition could lead be motivated to analyze and evaluate recipes from cookbooks according to their nutritional value. They might address the feasibility of reproducing the recipe with local ingredients. Finally, students might create their own cookbook. Each of these activities is aimed at developing competencies (1, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 11). If students are concerned about the problem of obesity in Mexico, they could learn some workout commands watching fitness videos. Afterward, students could create their own fitness routines. Their new fitness routine could be demonstrated at a festival (in order to meet generic competences, No. 3, 4 and 8). To develop more competencies students should keep logs about how they have overcome these challenges. They should evaluate themselves and other members of the group in order to ensure collaboration.

Even though the use of authentic materials will need careful planning to select and adapt them to specific competencies facing real problems, such competencies provide a framework of the linguistic repertoire used in places where English is spoken. An honest analysis will call for teachers to become life-long learners in order to implement increasingly useful and meaningful new visions of education where everybody can learn from each other. This is especially true with the arrival of new technologies and new media in which our students are likely to be more proficient that their teachers. Materials and methods will be, in this case, just a way access a different kind of education where students will develop as integral human beings facing the dilemmas of the 21st century.

References

Ban, R. (2009). Then and now Inglés en primarias. MEXTESOL Journal- Special Issue: Teaching English to Younger Learners, 33, 1. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://www.zoltandornyei.co.uk/uploads/1995-celce-murcia-dornyei-thurrell-ial.pdf.

Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://www.zoltandornyei.co.uk/uploads/1995-celce-murcia-dornyei-thurrell-ial.pdf.

Celce-Murcia, M., Dörnyei, Z. & Thurrell, S. (1995). Communicative competence: A pedagogically motivated model with content specifications. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6, 2, 5-35. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/2928w4zj.

Chamot, A. (2004). Issues in language learning strategy research and teaching. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 1, 1, 14-26. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v1n12004/chamot.pdf.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49, 222-251. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1169960?uid=3738664&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21104530601243.

Díaz, B. A. (2006). El enfoque de competencias en la Educación. ¿Una alternativa o un disfraz decambio? Perfiles Educativos, XXVIII, 111. Retrieved on 28 July 2014 from: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-26982006000100002.

Espinoza Hernández, J., López López, J. L., Tapia Curiel, A., Mercado Ramírez, M.A., & Velasco Lozano, E. (2008). Propuesta Metodológica para la Implementación de Programas en Competencias Profesionales Integrales. México: UDG. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://www.cucs.udg.mx/revistas/propuesta_metodologica.pdf.

Hearn, B. & Hopper, P. (2008). Instructional strategies for using problem-based learning with English language learners. MEXTESOL Journal, 32, 8, 39-54.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and Learning in the Language Classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hymes, D. (1972). Models of the interaction of language and social life. In J. Gumperz & D. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication (pp.35-71). New York: Holt, Rhinehart & Winston.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mendez, E. (2007). A case study approach to identifying anxiety in foreign language learners: A qualitative alternative to the FLCAS Anxiety Scale. MEXTESOL Journal, 31, 3, 69-86.

Moore, S. & Sayer, P. (2009). Sheltered English instruction: An overview of the model for younger learners. MEXTESOL Journal, 33, 1, 87-102.

Perez, M. (2011). Competence-Based Education. How are Competence-Based Education and Content-Based Education different? Classroom link electronic journal. Retrieved on July 28, 2014 from: http://pearsonclassroomlink.com/articles/0211/0211_0501.htm.

Richards, J. (2009). The changing face of TESOL. Plenary address at the TESOLConvention in Denver USA. Retrieved on July 29, 2014 from: http://www.professorjackrichards.com/wp-content/uploads/changing-face-of-TESOL.pdf.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the ‘good language learner’ can teach us. TESOL Quarterly,9, 1, 41-51.

SEMS (2007). Creación de un Sistema Nacional de Bachillerato en un Marco de Diversidad. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública.

SEMS (2009). Programa de Estudios-Inglés. México: Secretaria de Educación Pública.

Tobón, S., Pimienta, J. & García, F. J. (2010). Secuencias Didácticas: Aprendizaje y Evaluación de Competencias. México: Pearson Education.

Zavala A. & Arnau L. (2007). 11 Ideas Clave. Como Aprender y Enseñar Competencias. Barcelona: Editorial Grao.