Language Teaching for the Future, Revisited

Andrew Littlejohn

It is always a salutary experience to reflect on how we saw things many years ago, the priorities we then had, and the urgencies that pressed upon us. It was thus with considerable pleasure that I accepted the invitation to comment on an earlier article of mine, published some fifteen years ago, when MEXTESOL was celebrating its 25th anniversary. This is all the more apposite when the topic is the future, as it is in this case.

The ominous arrival of a new millennium was something that weighed heavily on us all in 1998, when the article was first published. The sense that we were marking the transition from one massive temporal landmark to another –the 20th to the 21st century – certainly provided a great sense of foreboding, heightened by talk of a ‘millennium bug’ (remember that?), a hypothesised glitch in the world’s computer systems which was to derail entire societies. In the event, as 1999 tripped over into 2000, no calamitous event occurred. A Friday became a Saturday and the world carried on as it had done.

This sense of continuation was very much the theme of the brief article republished here now. The article did not predict some cataclysmic event which was to have untold ramifications for language teaching. Rather, it explored the continuing evolution of features of Western societies in 1998, and from which I suggested implications for a ‘futures curriculum’ for language teaching. So, now, fifteen years later, was I right? Or did I miss the emergence of some significant development? And do my proposed implications for a futures curriculum still apply? At this point, I suggest you now read the article, and then come back to read the remainder of this introduction.

***

The theme of the social location of language teaching is an area which I have continued to explore, and I have since published a number of related papers, looking at both methodology and materials development as historically located practices (see Littlejohn, 2012 and Littlejohn, 2013, freely available on my website www.AndrewLittlejohn.net). Perhaps my main observation on the list of societal features set out in the original article is that the speed and extent of developments has far outstripped what anyone anticipated. In the years since 1998, the fragmentation of societies has continued apace – it is commonplace to talk of us each having ‘multiple identities’. National governments now exert far less influence over their societies and economies, as globalisation has become a fact. New technologies have spawned new forms of work whilst simultaneously rendering obsolete many occupations of the past. Electronic media is everywhere, with social networking now linking people together across the world in ways hitherto unimagined. And as a background to all of this, the force of the market has expanded, such that we are all now consumers, notonly of the plethora of goods now on offer, but in virtually every aspect of our lives, as services such as medicine, education, welfare and travel are now promoted as products or experiences to be bought and sold

It is perhaps in relation to this last aspect of social change that my review was most understated: the neoliberalist dream, in which state intervention and state support are effectively eliminated and the provision of services is increasingly handed over to the market – private enterprise - now characterises more and more societies. Certainly, we now see wider gaps between rich and poor than ever before, particularly in developing economies such as Mexico. This trend has not happened without considerable resistance, such as the Zapatistas movement and, more recently, the global ‘Occupy’ protests.

But what has this got to do with language teaching? Oddly enough, quite a lot in fact, all of which points to significant dangers for us. Here, let me just pick up on two of the themes I mentioned: the rise of digital media and the march of a neoliberalist ideology.

As electronic media have become more commonplace, language teaching has passionately embraced the possibilities for the classroom. Electronic whiteboards, tablet learning materials, computer assisted testing, and networked learning are all features of the modern classroom. And yet, in our enthusiasm for modern technology, there is a danger that we will forget where we have been. The heyday of communicative language teaching taught us the importance of a learner-centred curriculum but so much of this can be pushed to one side as electronic whiteboard activities bring the teacher fully centre-stage again, as highly technologised teaching materials make it difficult for teachers and learners to flexibly choose how they want to work and on what, and the cramped offerings of ten-inch screens prevent a clear overview of where they have been and where they are going. The improvised, spontaneous, holistic approach advocated by CLT does not fit well here. Detailed, atomistic syllabus items seem to be much better suited to the new click-through teaching technologies. It seems as though language teaching has never quite managed to shrug off its behaviourist past, and now it is coming back to haunt us.

From a wider perspective, the return to atomistic, bit-by-bit syllabuses harmonises with broader social tendencies. I spoke just now of the march of neo-liberalist ideologies, in which every aspect of human interaction becomes subjected to the market. For this to happen, services, such as education, need to be ‘commodified’, that is converted into standardised, packaged products which can be bought and sold. Perhaps unwittingly, language teaching professionals have become complicitous in this process. We can see this in the bewildering range of language exams now on offer, and the way in which ‘good teaching’ and teacher certification are becoming globally standardised (through such things as CELTA, Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults). Deeper still, the mapping out of what is to actually happen in classrooms is now increasingly prescribed through a highly centralised document, developed far, far away from most teachers and students implementing it: the Common European Framework (2001). While the designers of the CEF levels say they make no claims about methodology, it seems likely that (largely mythical) item level descriptions of student abilities, such as those contained in the CEF levels, lead to item level testing, and inevitably towards item level teaching. Potentially, therefore, we have uniformity in classroom experiences emerging worldwide, through a detailed scripting of the interaction of teachers and students (see Littlejohn, 2012 about the processes of McDonaldisation in language teaching materials).

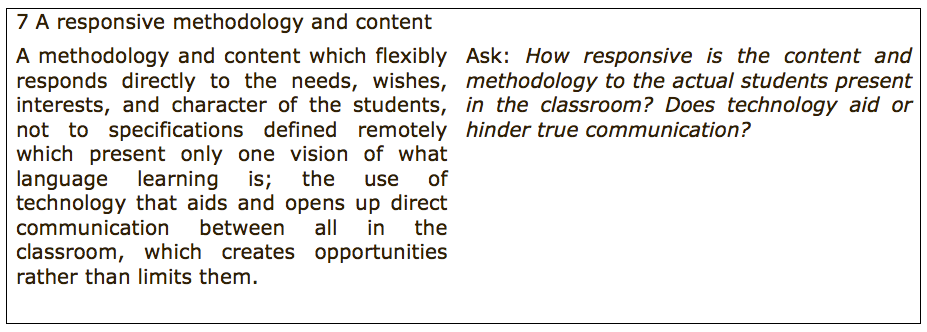

My original article suggested some characteristics of a futures curriculum. All of the points listed there still hold, but with perhaps a stronger sense of urgency in resisting the forces of standardisation. We need, I think, something of the Occupy mindset here: a spirit of resistance against the extent of standardisation which is being enforced, against the process in which curriculum decisions are being removed from those directly involved with their implementation, and the gradual erosion of the freedom to imagine a different way of doing things. To the set of six questions listed at the end of the original article, therefore, I would add another one to evaluate present practices:

References

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Littlejohn, A. (2013). The social location of language teaching: from zeitgeist to imperative. In Azra, A., Hanzala, M., Saleem, F. & Cane, G. ELT in a Changing World. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Available at www.AndrewLittlejohn.net.

Littlejohn, A. (2011). Language teaching materials and the (very) big picture. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching. Vol. 9, Suppl. 1, 283–297. Available at www.AndrewLittlejohn.net and http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/main.htm.

Language Teaching for the Future [1]

Andrew Littlejohn, Institute of Education, University of London [2]

First published in MEXTESOL Journal, Issue 22/2, 1998.

The prospect, it seems, of a ‘new millennium’ has captured our imagination. In Britain, as elsewhere, there have been great discussions about how we should celebrate this historically significant event. Like the onset of a new year, however, a new millennium also marks a moment when it is appropriate to think about what we have done, where we are now and how we should plan for the future. By all accounts, we are in a period of rapid change—socially, politically, technologically, environmentally and culturally. It is likely, for example, that people who are now in their twenties, thirties or forties will experience significant changes in their working lives in the years ahead. Younger people (who may for example be around sixty in middle of the next century) will grow up into a world quite unlike the one we inhabit now. The significance of these changes has led many educationalists to call for a “futures curriculum”—that is a curriculum which actively discusses the future and prepares students for their lives ahead. In this short article, then, I want to consider what, our role as language teachers could be in this. That is, what it might mean to talk of “language teaching for the future”. My aim is to stimulate discussion—to be provocative, in fact. To do this, I will discuss two related questions:

• What will the future be like?

and from that,

• What should we be doing now to prepare our students for the future?

What will the future be like?

Predicting the future is always a hazardous business. Natural occurrences, catastrophes, sudden unexpected events all make it impossible to reliably describe what the future will be like. But we can make reasonable predictions. The future won’t just suddenly happen; the nature of the future exists in our present. It is here that history can help us. If we look back at our recent past, we can identify trends which are likely to characterise the nature of future societies. Social scientists working in this area have identified a number of aspects which they suggest will typify future ‘post-modern’ society, as they call it (‘post-modern’ being what comes after ‘modern’ times). These characteristics refer principally to the West, but with the advent of ‘globalisation’ they will be increasingly relevant everywhere. Some of the more significant of these are:

- a fragmented society: A society divided into smaller ‘communities’ which extend across national borders. The notion of a ‘culture’ (shared by all) will be replaced by ‘cultures’—in which meanings, customs, habits, and references will vary considerably, even within the same geographical area.

- decline of national governments: ‘Globalisation’ as a dominant feature, limiting the power and relevance of national governments. Supranational governments and businesses will exercise greater influence.

- rapid (dis)appearance of jobs: Technology will cause the disappearance of many types of jobs, but also the emergence of new ones. In their lifetime, individuals may expect to have ten or more different occupations. Making choices, decisions and adapting will be essential.

- spread of ‘the market’: The force of the market (advertising, consumer products, cost/profit analysis, etc) will be evident in all spheres of life: education, health care, religion, the family, etc. Globalisation will also lead to standardisation in the market - the same products will be available everywhere.

- influence of electronic media: Electronic media (television, computers, interactive video) will dominate as the principal means by which people receive information and spend their leisure time. Electronic media will far outweigh, for example, the influence that the school may have (already, estimates suggest that by the time the average student has finished high school in the USA, they have spent 11,000 hours in class, but over 22,000 in front of a television).

- ‘endlessly eclectic’ An emerging characteristic of many societies now is the manner in which the elements from very different areas of life are combined. Images from traditional life in Africa, for example, are used to advertise fashion clothes. Individuals can decorate their homes to look like houses from hundreds of years ago. Pop stars sing and politicians speak at the funerals of royalty. At the same time, the limits on what is expected are breaking down— with the result that it is becoming increasingly difficult to be really ‘shocked’. ‘Expect anything’ is the best advice.

Each of these trends, social scientists suggest, are likely to become more evident in the years ahead. Whether they are good or bad depends, of course, upon your own individual point of view. What is clear, however, is that there are dangers. The increasing dominance of electronic media, globalisation and the dominance of multinational organisations, all pose dangers for democracy and individual freedom. Similarly, the spread of the ‘market’ may also pose dangers for the integrity of social services such as education, where economic efficiency may not always be compatible with educational goals. What this suggests, then, is that we need to be aware of what is happening so that we can make the future as we would like it to be, and not simply drift forward.

What should we be doing now to prepare our students for the future?

Language teaching practices today

The description of emerging characteristics of a future society may seem very remote from the day to day moments of language teaching. In reality, however, language teaching is a part of society as much as anything else. It is not difficult to see, therefore, signs of a ‘post-modern’ society already present in contemporary practices in language teaching. A survey of published course books for school-aged students, for example, can identify some significant characteristics. The following are based on my own observations which you may or may not agree with.

Language learner as consumer The content of language exercises may be centred around performing commercial transactions (e.g. ordering hamburgers and cola in a restaurant) or expressing preferences about consumer items (e.g. fashion clothes, pop music, pop stars, and videos).

Fragmented, eclectic content A‘unit’ of materials may be composed of seemingly random content—linked together perhaps by an underlying grammatical thread. A newspaper article about a protest may be followed by a listening passage on UFOs, which may in turn be followed by a role play to solve a murder—all intended to present examples of the past tense. (“Expect anything” being also suitable advice to a language student.)

Significance Meaning has long since been important in language teaching, but beyond this there is also the matter of significance. On the one hand, much of the content of language teaching tasks appears to focus on what is essentially trivia. On the other hand, the true significance of something may be disregarded in the pursuit of a syllabus item. A text about the first tests of a nuclear bomb, for example—potentially one of the most significant events in modern history—may be made the focus of class work simply for the form it exemplifies (“What were the journalists doing when the bomb exploded?”). Similarly, a storyline about a boy stealing cigarettes from a shop may be used to practise language forms (“What was the boy doing when the girl saw him?”) without the morality of the action being questioned.

Standardised lessons Although teaching practices and teaching materials have become much more interesting for the learner in recent times, one element in this has been the growth in standardisation of teaching practices. Superficially, part of the cause of this has been the emergence of global course books, which propose similar classroom work in diverse situations and cultures. Additionally, global teaching qualifications are potentially leading to a standardised view of what ‘good teaching’ is. I say, superficially, however, because it is not the fact of globalisation that is important here, but what an individual course book or teaching qualification may actually propose. It is perfectly possible to imagine classroom activities which although standardised in their procedure actually produce ‘unique’ outcomes each time they are used - brainstorming tasks, for example. In contrast, however, my own view is that there is increasing tendency towards detailed ‘scripting’ of lessons - standardised lesson procedures with standardised content that are re-enacted all over the world. This means, for example, that students and teachers on opposite sides of the planet, in widely differing contexts, can end up working with exactly the same language, through the same standard closed tasks, producing more or less the same outcomes.

A ‘futures curriculum’ in language teaching

I said earlier that I think that it is important that we are aware of how society is evolving so that we can try to make the future as we would like it to be. As an educational activity, there is thus a particular responsibility for language teaching. On the one hand, we need to think about how we can help to prepare our students for the very different demands that the future will make—the need to be able to make rapid decisions and adapt, for instance. On the other hand, we also need to look beyond the concerns of the language syllabus, and not simply drift with the flow of post-modern development. We need, for example, to think about the content and significance of our materials, the values and attitudes we project, the kinds of ‘mental states’ we are fostering—how, indeed, we contribute to the way the people see themselves.

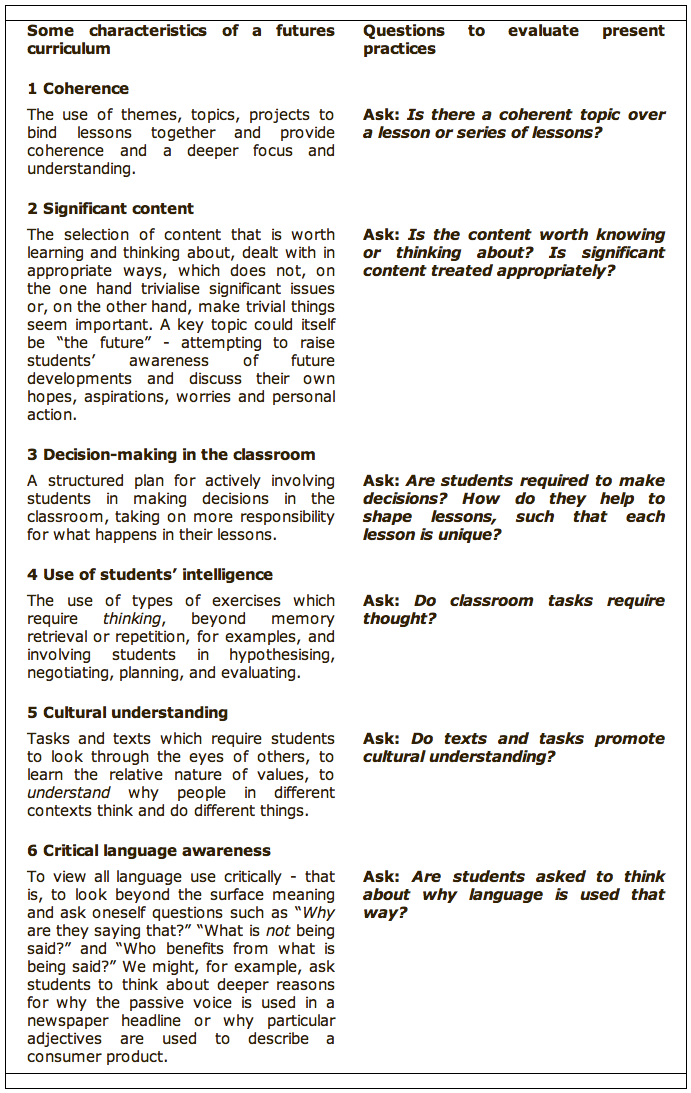

A futures curriculum for language teaching, then, will be based not only on what our students are likely to need but also on a vision of how we would like the future to be—how we need to guard against dangers and shape the way we wish to live. This is, of course, a very subjective matter which will vary from individual to individual, culture to culture, but to end this article I would like to set out six principles that I think could underpin developments in language teaching. As a set of ‘desirable’ characteristics, they may also function as a means of evaluating what we are doing now, so for each one Ihave added a question which we can use to review our present practices.

[1] This article is based on a plenary given at the 1997 MEXTESOL Convention in Veracruz. It is an invited paper.

[2] Other articles by the author are available free of charge from the following web address, where you will also find a complete on-line A-Z of ELT methodology: www.AndrewLittlejohn.net.