Nowadays there is an increasing interest to approach the study of L2 learners’ beliefs as complex constructs interrelated with social reality. Those who have studied the topic using such approach have characterized L2 learners’ beliefs as emergent and contextually bound. These features have been observed as connected to factors such as teachers’ beliefs (Allen, 1996; Barcelos, 2000), classroom mediation (Peng, 2011), social interaction (Navarro & Thornton, 2011), the clash between learners’ expectations and reality (Kalaja, 2006; Malcom, 2005), and the influence of peers’ discourse (Alanen, 2006). Simultaneously, some have inquired into the possible relations between beliefs and other factors like learners’ personal agendas (Cotterall, 2005), learning strategies (Hosenfeld, 2006), emotions (Aragão, 2011), and identity (Barcelos, 2006). Likewise, others have focused on identifying the role of specific beliefs in the context of particular learning experiences. For instance, Bellingham (2005) analyzed the views of mature learners about the role of age in L2 learning, Murphey and Carpenter (2008) explored the notion of agency attribution, and Mercer and Ryan (2010) compared the beliefs about the value of attitude and effort in L2 learning. In sum, these studies suggest the existence of intricate connections between beliefs and context.

In recognition of such complexity, some researchers have tapped into learners’ experience from the vantage point of their personal histories (Kalaja, Menezes, & Barcelos, 2008). In other words, an individual’s life experience may offer a holistic understanding of how beliefs are generated out of learners’ interaction with the surrounding socio-cultural forces (Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001). Therefore, the narrative turn that has spread in the study of L2 learners’ beliefs attempts to respond to the complex nature of the task at hand: understanding beliefs as social constructions. Following this trend, the present study focuses on L2 learners’ narrated experiences with the purpose of observing how L2 learning is intrinsically connected to social action in the context of a Study-Abroad Experience (SAE).

Theoretical Framework of the Study

Although the etic perspective has undoubtedly contributed to the development of SLA, some scholars have emphasized the merits of focusing on the individual (Jones, 1994; Oxford, 1995). It has been argued that, only by in-depth and long term analysis of individual cases, we can achieve a better understanding of the “flesh and blood” L2 user (Kramsch, 2009, p. 2). This holistic interest has led some researchers to capture not only the contextual element, but also a longitudinal perspective through the analysis of learners’ narratives.

Research within this perspective has pointed out that certain social factors have an impact on the opportunities that L2 speakers perceive, encounter and actually pursue to use their L2. Some of these studies have focused on L2 users in situations of permanent immigration (Norton, 2000), while others have explored the experiences of English native speakers during a SAE (Kaplan, 1993, Kinginger & Farrell-Whitworth, 2005, Pellegrino Aveni, 2005). This research has highlighted the influence of sojourners’ attitudes and identities on their L2 development or lack thereof.

In a similar vein, some researchers have produced evidence on the SAE of L2 learners of English. For example, studying four students from Hong Kong, Jackson (2008) observed that two of her participants did not perceive that their hosts acknowledged their identities of ‘Hong Kongers’ as different from Chinese mainlanders. This lack of validation eventually discouraged the sojourners from interacting with the target language culture (TLC), losing opportunities to use English. Similarly, following the identity journey of another Hong Kong native, Chik and Benson (2008) found a striking clash between the participant’s beliefs about her L2 learning prospects and the discriminatory attitudes she perceived in England. As a result, the learner not only changed her views on her possibilities to acquire a native-like pronunciation, but also modified her perceptions of the host culture. Also, in just a few months in a SAE, the two learners studied by Yang and Kim (2011) changed their beliefs about the supposedly beneficial role of exposure to the TLC for the development of L2 proficiency. Another study (Amuzie & Winke, 2009) reports changes on beliefs about learners’ and teachers’ roles and few opportunities to interact with the host culture. Nevertheless, these studies focus mainly on one aspect of the phenomenon: the beliefs generated in a SAE by contact with speakers of the target language. The impact of learners’ interactions with other social and linguistic groups is less discussed. Moreover, as the studies that focus on L2 English users mainly feature Asian students, more evidence is required from learners coming from different cultures.

In this context, Barcelos’ (2000) dissertation offers evidence of L2 learners from a different cultural group. In her study of three Brazilian learners, Barcelos demonstrated how learners’ beliefs about L2 learning somehow contrasted with those of their respective American teachers. Although this study focuses mostly on learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of classroom practices, the findings leave a door open to ponder the role of beliefs about the TLC and their impact on L2 learning.

In studying learners’ conceptions about the TLC, it is important to consider how L2 learners’ beliefs relate to social interaction during a SAE. From a socio-cultural point of view, it would be expected that this relationship should be dialectical: in other words, interrelated and dynamic. Furthermore, a complete picture of the phenomenon requires multifaceted lenses, considering not only the contact with monolingual target-language speakers, but also with other multilingual groups, and the available L1 community (L1Co). Therefore, the present study takes a socio-cultural stance to explore how social interaction is related to L2 learners’ beliefs about the TLC and the relationship of this multifaceted interaction with L2 learning. The research questions which guide this study are as follows:

1. Do L2 learners’ beliefs about the TLC evolve as learners interact with different social groups in a SAE?

2. If so, how does this evolution occur? If not, why not?

It is also important to clarify that in this study, I adopt a view of culture as Discourse. Therefore, whenever the concept TLC is used, it should be understood as “ways of using language and other symbolic expressions, of thinking, feeling, believing, valuing, and of acting” (Gee, 2008, p.161), that the participants identify as characteristic of the target language speakers. At the same time, the group of individuals thus identified –mainly European American speakers of English (Wolfram & Schilling-Estes, 2006, p. 18) in this study– will be referred as the L2 Community (L2Co).

Research Design

This study analyzes the L2 learning careers of three Mexican L2 learners of English, adhering to a view of narratives as doors to the beliefs systems embraced by the narrators. It can be considered an “analysis of narratives” (Polkinghorne, 1995) since it gathers a collections of ‘stories’ from semi-structured interviews and observations to identify common themes emerging from the data. The purpose was to establish connections between the learners’ subjective world and the actions in which the learners were involved.

The contact with the participants was maintained for nine months, during which they were interviewed three times each and observed in their English composition classes (3 observations). In the first interview, the initial question was designed to encourage an impromptu narrative of the participants’ L2 learning history. The other topics in the interview guide explored the learners’ views on different aspects of language learning, such as reasons to learn an L2, agency, and the degree of pleasure that the learners perceived in language learning. Only the last question encouraged the learner to draw comparisons between their initial L2 learning and their SAE. However, the topics suggested in the guide were adapted as the interview evolved depending on the conversational style of each participant and the content of their first answer. The second interview was used to compare and contrast the participants’ points of view about their class experience with mine as a non-obtrusive observer during these lessons. Finally, in the third interview I used a guide that emerged from a preliminary content analysis of the data, considering the collective findings of the first interview. I conducted the interaction so that the participants could feel free to explore alternative paths in their narratives if they desired it. This format allowed the participants to produce further narratives of their experiences as we progressed through the sections of the semi-structured interview. With each participant, the first round of interviews lasted an average of 45 minutes, and the other two took approximately 30 minutes each (see Appendices A, B, and C).

The observations centered on the learners’ interactions with other students in the context of an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) class. As a requirement of their host university, two of the participants took a course that focused on academic writing, while the third participant had been placed in a four skills class. During the lessons observed, neither audio nor video recording devices were used, since other students in the class and the instructor were not participating in the study. However, detailed field notes were collected. The observation field notes were used to compose narrated accounts of each lesson which were included in the data analysis.

I analyzed the data in three phases following the method of constant comparisons (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), with the aid of NVivo 10. In the first phase, I conducted an initial round of open coding on the first interviews, which allowed me to define the aspects that I wanted to observe more intently during the lessons. During the second stage, I practiced open and axial coding on data after the class observations and second interview. This analysis gave way to the final interview guide. By the end of the study, the participants were requested to read the manuscript to check if their points of view had been properly represented, and this served as a member check.

The Participants

At the time of data collection, the participants were pursuing a business-related master’s degree in a major university in the Midwest of the United States. The sojourners, who will be referred by the pseudonyms of Elena, José, and Silvia, were part of an exchange program and had similar socio-economic backgrounds. The three participants had studied in research-oriented universities ranked among the top 20 in Mexico (UNAM, 2012). After graduating from college, the learners enrolled in a multidisciplinary graduate program which offered a year of coursework abroad. It was not until their arrival in the US that the three participants met each other.

First Contact with the Participants

The participants were selected through a purposeful sample. I met José and Elena in a social gathering during the summer of 2012. The occasion was propitious to establish an initial informal rapport with them as my fellow-country people, but the conversation was kept in English because our host was not a Spanish speaker. So, I had a good opportunity to observe their L2 use since that first occasion. Nonetheless, in the subsequent informal encounters that I had with them, in which I also met Silvia, most of the communication was conducted in Spanish. It was not until they had consented to participate in the study, that I had the opportunity to converse with them in English once again. During the months that followed, I maintained a friendly rapport with the three participants with whom I often casually met in campus. However, I did not take the friendship to a deeper level, in order to maintain equilibrium between my role of friendly acquaintance and researcher. In the following lines I provide more details on each of the cases

Elena: A Top L2 Learner

Elena’s father is a medical doctor with a successful practice in one of the largest cities in Mexico. Since Elena’s early childhood, he had insisted that she should acquire English as a way to secure future professional advancement. Elena had followed her father’s advice gladly. In fact, she mentions that she always enjoyed English lessons, having been promoted to more advanced classes in her elementary school years. Always at the top of her L2 class, Elena, unsurprisingly, began to consider herself as a good English learner. Moreover, when she reached adolescence, she was sent to a private institute to refine her proficiency. She identifies this time as the most helpful in her L2 development. Consequently, Elena’s confidence increased even further. When she entered college to major in computer science, she perceived her proficiency as more advanced than that of her classmates and judged the content of her English courses as too basic for her level.

Elena never enrolled in a specific course to prepare for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). Actually, when she applied for admission to the study-abroad program, she sat for the TOEFL iBT (Internet Based Test) without any specific preparation. Elena obtained a score of 88 which, according to Tannenbaum & Wiley (2008), ranked her as an upper intermediate user, at the B2 level in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Before her arrival to the US in the summer of 2012, at 22 years of age, she had neither travelled abroad nor been away from home for an extended period of time.

José: The Extroverted L2 User

Both of José’s parents had a college education and speak English to a certain extent. Additionally, his maternal grandmother was an English teacher. Therefore, it is not strange that José was purposefully enrolled in private schools where English was part of the curriculum since pre-school. However, he switched to the public system in high school, enrolling in a program administered by one of the most prestigious public universities in the country. José’s ultimate goal was to be admitted in that university. Obtaining a high school diploma from the same public institution was strategic to ensure his admission in a university that yearly rejects over twenty thousand applications (Rodríguez Gómez, 2004). Nevertheless, the contents of the English courses in public schools were below José’s learning needs. So, like Elena, José attended a private institute to keep improving his English proficiency, and at the same time, he took up German. In both cases, José had chosen to learn foreign languages because he believed that they would make him more competitive once he entered the job market.

Notwithstanding these seemingly well-defined goals, José’s investment in foreign languages declined during the time he majored in business administration. Having a boisterous and gregarious personality, he preferred using his free time to work in a part-time job and socialize with friends. Simultaneously, he had the opportunity to briefly put his proficiency to test during a few trips to the US to visit relatives. These experiences gave him confidence in his ability to establish communication using his L2, without regard to his frequent accuracy problems. Apart from that, his formal L2 development was put on hold until his first year in graduate school when José was 27 years of age. As he finally decided that he wanted to study abroad, he enrolled in a summer course to refresh his English. This move turned out to be useful, since he barely managed to score 79 in the iBT that year, qualifying as a lower-intermediate learner in the CEFR (Tannenbaum & Wiley, 2008) and as the least proficient speaker among the three participants.

Silvia: The Naturalistic Acquirer

Silvia’s father is a researcher in a biology-related field. During Silvia’s childhood, he obtained a doctoral degree in an American university. Silvia and her mother joined him there for an academic year. In that time, Silvia remembers having acquired English to the point of using it for daily communication, both at school and at home, even if her parents preferred using Spanish. At her return to Mexico, at the age of seven, she was enrolled in a private elementary school in which English was part of the curriculum. Nevertheless, for Silvia, the contents of her English classes were below her proficiency during all her elementary education. In junior high, Silvia was sent to a bilingual private school that had a more demanding curriculum. That was the first time Silvia faced more challenging grammar instruction. In spite of this perceived difficulty, the classes in the bilingual school should have helped her somehow to move forward or maintain her English proficiency, since that was the last formal contact she had with English in many years. It was not until she had finished her undergraduate coursework as an agricultural major, when she had to use her English again.

Silvia worked in Canada for six months as part of an internship program. For the first month, she worked as an interpreter for the manual workers of the company who were of Latin American origin. She would basically interpret in Spanish the instructions given in English by a Canadian manager. Later, Silvia was assigned to supervise the production of bell peppers in a green house, silently working with a checklist. Unexpectedly, her best opportunity to practice English came in her free time, because her boss often invited her to socialize with her daughters.

After this brief period, Silvia returned to Mexico. She used the following years to prepare her thesis defense and get her first steady job. However, since her next goal in life was to get a graduate education, she applied for a grant to study for a master’s degree that offered a year of coursework in the US. When she took the iBT, her L2 proficiency was ranked at the same level as Elena. With all these previous experiences, Silvia set off for the US again. She was 26 years old.

Findings

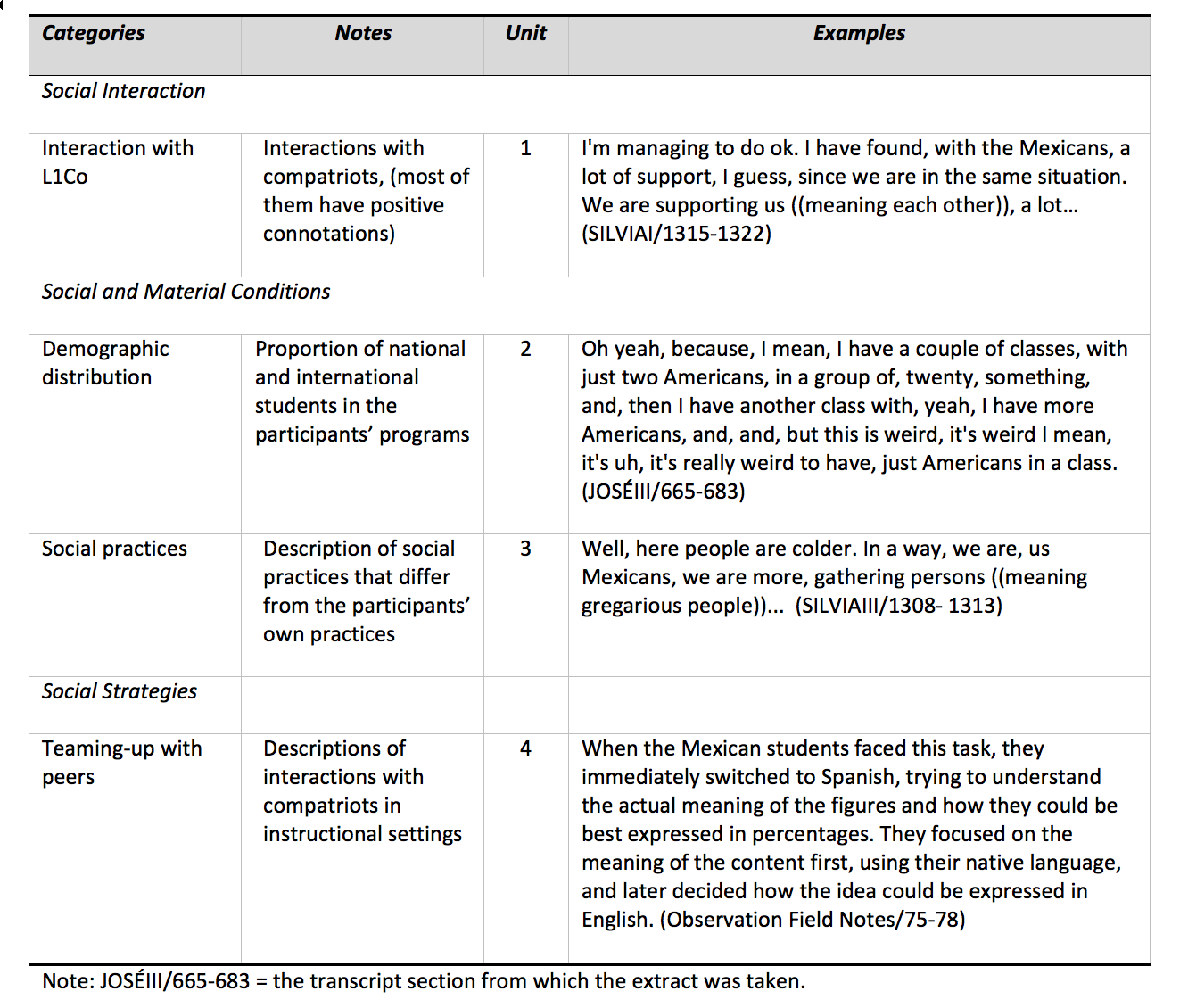

The participants’ L2 learning careers had rather dissimilar beginnings; however, as they advanced in their SAE, the shared experiences began to reshape their perceptions in ways that emerged as a set of common beliefs. The data suggest these adjustments eventually impacted their actions and their learning. In this article, I focus on three main categories that emerged as connected to these changes: social interactions with the L1Co and the L2Co, social and material conditions, and learners’ social strategies. Table 1 shows descriptions and data examples of these categories as organized during the axial coding.

Table 1. Examples of coding categories and data excerpts.

Social Interactions

The data showed an intense socialization with the group of compatriots that were part of the same program. Since their arrival, the participants reported a strong reliance on their L1Co, as it can be observed on Silvia’s comment (Table 1, Unit 1). Contrastingly, the participants’ relationships with members of the host-culture were qualified as superficial. In her interviews, Elena concluded that those interactions had been essentially impersonal, even when she hedged her comments with extensive explanations on how her American interlocutors had been generally polite with her:

I mean my boss is really nice, well he's, uh, he's kind, he's polite, he's chatty, so, he will be, he will be like, talking about his life and, I don't know, things like that and, it's ok, but it's not that, uh, it's not that friendly really, relationship I mean, it's just, boss, uh employee, that's it. (ELENAIII/738-762)

This perception was not only circumscribed to the boss-employee relationship described on the table, but was also reported in Elena’s account of her interactions with most L2Co members:

I mean, they ((the Americans)) respect you and, I didn't have any kind of, umh, situation where I felt, uncomfortable or anything, uh, but they don't uh, try harder to get to know you. I mean, if you go and ask them, and try to have a conversation with them, they will be friendly, and they will give you the information that you want, but that's it. They don't go any further than that. (ELENAIII/708-726)

As time went by, the participants’ relationships within the L1Co intensified, while their beliefs about their hosts were reinforced, not only by first-hand experience, but also by the shared discourse generated whenever they discussed the topic within their L1Co. Silvia talked about this discursive construction in her last interview:

INTERVIEWER: Ok, interesting, and you mentioned that you didn't have a chance to make so many American friends...how can you explain that?

SILVIA: I guess they don't like to make friends. I don't know, I, we, I've talked this with uh, my other Mexican friends, and we got to the same point, and we don't have American friends... (SILVIAIII/255-273)

In trying to make sense of this perceived alienation from the L2Co, the participants alluded to the different contextual conditions that pervaded in their campus, described in the following section.

Social and Material Conditions

Apparently, three main contextual elements placed the learners in a position of isolation from the host culture: the housing and transportation system, the demographic characteristics of the student population, and the practices that regulate social interaction in the TLC. To understand the first of these contextual elements, some precisions about the material conditions of the host university are required. To begin with, since the university is located in a small town, only limited public transportation services are available. In the following excerpt, José describes how these circumstances forced him and his peers to walk whenever they explored the town (with temperatures above 100° F):

Well, at first, well, we, all the Mexicans, came, most of the same days, so, this city was on vacations, because this is a university town so, if the university is on vacation, the town is kind of dead... So, we didn't have a way to, umh, to move ourselves. We have to walk a lot. (JOSÉI/213-217)

Unsurprisingly, these conditions were determinant to discourage more interactions with the off-campus area, and simultaneously the shared experience increased the cohesion of the L1Co. Therefore, in the participants’ host university it is not uncommon for international students to favor on-campus housing, especially if they do not own a car. On the contrary, most national graduate students prefer off-campus housing because it is relatively inexpensive and less restricted. These factors contribute to the consolidation of what Gallagher (2013) calls “an international ghetto” within campus, which segregates the students from the L2Co (p. 61). For instance, José, who had first expressed the desire of having an American roommate, by the end of his stay, was fully aware of the impossibility of his original plan.

I think the most important thing that we all want to do, as soon as we get here is, try to live with American people, but that's almost impossible because these apartments are mostly for international, and, because we have to like, get it all ((meaning furniture)) and, they already have, and they already live in some part of America, which make the whole transition easier for them, because, for us, we have to buy furniture, and stuff so, we try to avoid that, and… that means that you have uh, a bus...so, that's kind of hard, just to find an American. (JOSÉIII/768-806)

Likewise, the demographic characteristics of the student population in the participants’ program also contributed to reduce their contact with the L2Co, because of the small proportion of American students enrolled (Table 1, Unit 2). Adding her own view on this circumstance, Elena made the following wistful comment:

Yeah, because for, in my major ((International Studies)) we don't have any, well, we don't have many, native, speakers of English. They're very few, and, we are more international students, and, it's good, but, maybe, more diversity could be good. (ELENAIII/528-538)

In this excerpt, Elena seems to be asking for more opportunities to interact with her hosts. Ironically, when she actually had the chance to be enrolled in a class with a greater presence of L2Co members, she did not assess her interactions with them very positively. This leads to the third and final contextual element in play: practices that rule social interaction in the TLC, which the participants identified as cold, or boring. Elena narrates her experience in the following terms:

ELENA: …there is a class, that I have, or, where, there are no Mexicans. Oh, the class is sooo boring.

INTERVIEWER: Really?

ELENA: Yeah, because uh, there are only Americans, maybe, another, a few international students. Well, we always sit in the table, by teams, so, I sit with my teamwork, and, uh, no, they're on their stuff. They don't talk, uh, when they make jokes, they make weird jokes, I don't find them funny... (ELENAII/471-506).

In José’s last interview, he tried to explain his failure to relate to his American peers in terms of the pervasive differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures.

JOSÉ: …they just have a different culture. They are very individualistic. …they are not as warm as Latin people, that kind of stuff. I think that's it.

INTERVIEWER: Why do you think they are not as warm as Latin American people?

JOSÉ: Well, they don't even kiss each other on their cheeks. When they say hi, they are really individualistic, which means that, we, as Latins, try to get everything in groups, and, we ask people to come with us, and they don't. They just do their stuff, and maybe they do have, uh, you know like, activities, with a bunch of people but, it's not something as, as we do. They are more, I don't know uh, strict in time and forms ((meaning they stick more to do things in due time and manner)), and they're very square ((meaning inflexible)), that stuff, and we're not at all. (JOSÉIII/707-748)

Therefore, the interlocutor with whom the participants expected to establish a dialogue appeared unavailable, and more than one contextual factor seemed to coalesce to preserve these conditions. This perceived isolation could have affected the participants’ mood more seriously if they had not resorted to two specific social strategies to cope with the stress of the SAE.

Learners’ Social Strategies

In order to fight loneliness, the participants relied on the support provided by two specific social networks: their compatriots and other international students. In the first place, the participants’ reliance on their L1Co was evident in the data since the initial interviews, but its role in classroom settings became more salient during the observations. For example, in their EAP class, Elena and José always sat together in company of a third Mexican peer who did not participate in this study. The three of them would normally team up if the instructor encouraged collaborative work, as opposed to the rest of the class that showed a passive resistance to work in small groups (see Table 1, Unit 4). Likewise, if the participants had a question during the task, their first impulse was to request help from their compatriots. Furthermore, during those moments of the lesson that the participants described as “boring” and when their attention began to drift off, the three Mexicans would cheer each other up with quiet playful banters in their native tongue. As I observed this behavior was a constant in more than one class, the topic received attention during the subsequent interviews. When asked about the role that her partners played in her classroom experience, Elena’s response was ambivalent:

Ummh, I like, I get distracted, maybe if I weren't, with them ((her Mexican classmates)), I would be, maybe, interacting with someone else, or, maybe paying more attention to the class, which doesn't mean that I would like it, ((laughter)), and, uh, I think that, uh, it's helpful, sometimes because, if I don't understand something, or, maybe if I, yeah, if I don't understand something, they can explain, and I will uh, understand better because they're speaking in my language. (ELENAII/421-445)

Although it is clear that Elena was aware that her interactions with her compatriots could be an element of distraction, she concludes her comment on a positive note, pondering the value of having a Spanish interlocutor as a mediator to facilitate her learning. On the contrary, Silvia’s experience in her EAP class was a lonely journey. Being the only Spanish speaker in the class, Silvia would normally sit in the first row and follow the class quietly. Only when the instructor required her to work with one of her classmates, would she come out of her shell. However, outside the classroom, I observed that notwithstanding her reserved nature, Silvia usually interacted with others. On most of those occasions, she would choose a compatriot to hang out with. In sum, when asked about this particular aspect of their behavior, the participants acknowledged that their constant interaction with their L1Co had worked as a double-edge sword. While it had served them well to combat loneliness, it had also reduced their L2 use and their potential proficiency gains.

Additionally, although the participants mostly relied on their compatriots to socialize, they eventually began to expand their circle of friends. When they did so, it was to include other international students of different native languages. This circumstance somehow made up for the participant’s lack of contact with the L2Co and, at the end of the program, these new relationships were valued as the best part of the SAE.

As it could be expected, the combined force of social interactions, social and material conditions, and social strategies eventually had an impact on the participants’ perceptions. The data analysis hints a connection between these societal factors and the participant’s beliefs evolution. I present some evidence regarding this association in the following section.

Beliefs about English and Paradoxes

A few weeks before the end of the SAE, I asked the participants to assess the impact of their SAE on their L2 proficiency and their professional development. In their assessment, the constructed idea of the L2Co as socially distant and cold seemed evident. However, at the same time, a certain hint of wistfulness in their answers suggested that they considered their lack of interaction with their hosts as their loss, especially as it concerned their L2 learning.

SILVIA: Umh, I haven't really talked that much English since I'm here, and that's, something I regret, because I don’t know, maybe, the culture. I don't know. I haven't had that many friends, American friends. (SILVIAIII/108-118)

INTERVIEWER: What would you like to, if you could change, what would you change?

ELENA: Ummh, maybe, having a circle of friends who speak English, maybe to practice more, to get to know them better. (ELENAIII/508-518)

INTERVIEWER: So, if you could change something, it would have been like having the opportunity to…

JOSÉ: Live with an American. (JOSEIII/830-835)

In these excerpts, the participants seem to associate L2 improvements to language use in everyday informal interactions with European Americans, which is what they lacked the most. Nevertheless, their overall evaluation was not totally tinged with regrets. In fact, it was rather positive. It is interesting to observe that although they were interviewed separately, the three of them spontaneously brought up the topic of their interactions with other L2 users as a positive note in their experience. The following comment instantiates this perception:

Uh, I like how, it's incredible how many people I met here from countries that maybe, I didn't even know that existed[1], uh, cultures I didn't even know, and how we can all communicate in English, that is like, the opportunity I've lived here. It has been very important, and, it's all because of English so, that is what makes it so interesting for me, to keep on learning, to keep on practicing because,…everybody tells you that English, and that learning English would open doors for you, and you never see it, and, now I'm here, and I've seen how I got to meet people because I knew a second language, which, was English. (SILVIAIII/375-409)

These repeated comments in the data represent the participants as pleasantly surprised to discover that their L2 ability had an unexpected additional value since it served them well as a Lingua Franca (Jenkins, 2012). Unfortunately, all those new interlocutors with whom the participants could use English as a Lingua Franca were not considered as the most reliable model of ‘good English’. In the participants’ minds, that role was reserved for the English non-native speakers:

I like to talk with Americans because, uh, if you're trying to speak their language, you prefer to talk to someone who really knows how to speak it, and, and you can find like different uh, accents in, you know like, Indian people and, Chinese people and, I don't know, maybe the Arabic guys have these funny accents so, I believe that, the best way to understand and improve your, English is listen to other American, people. (JOSÉ/382-390)

Also, when asked whether their views of America and the Americans had changed during their SAE, the participants admitted certain adjustments on their beliefs.

Uh, well, what I thought before is what I saw in the movies, or shows, which is very different here, because those shows are focused on cities, that are bigger than here, and, and have different uh, values maybe, and, here it's very familiar ((meaning perhaps family-oriented)), or the college environment, so it's different, but I didn't have the chance to share time with American people. It was only in my job or, maybe some meetings but, that's it. It changed because I thought they were more friendly, in the, aspect of hanging out with you, or getting to know you, and they're not ((laughter)) that much. (ELENAIII/668-709)

Therefore, while the participants’ discourse conveys a general satisfaction with their SAE, the positive view is their contact with other international students. It is also through the contact with their international peers that the learners had more opportunities to use their L2. Ironically, even if the participants reveled in their discovery of ELF, the image of the ‘native speaker’ as the L2 model and main interlocutor remained in the participants’ minds.

Finally, when the participants assessed their improvements using L2, they agreed that their academic writing skills had improved. In contrast, Elena and José acknowledged that their colloquial English had not been properly developed during their instruction in Mexico, and this gap had affected their communication during their sojourn.

Discussion

In sum, the data show that social interactions, social and material conditions, and social strategies in the study-abroad scenario led the participants to adjust their beliefs to make sense of their experience. While some of their perceptions confirmed their preconceived ideas concerning the TLC, in other instances they had to revise and modify their beliefs. As these modifications took place, the learners’ actions were also impacted. Thus, the analysis shows that the evolution of learners’ beliefs happened in a reciprocal relationship with the social and material forces. In other words, although beliefs adjustment is commonly characterized as an internal mental process (at the intra-personal level), the evidence suggests that they were rooted in a socio-cultural medium (social material conditions, and social interactions in the data), or the inter-personal realm based upon Lantolf and Pavlenko’s (2000) terms. At the same time, what happened within the participants’ beliefs system was coupled with concrete linguistic choices and led to specific actions (strategies). Hence, the relationships in this analysis are described as dialectical for their interactive nature. In this section, I discuss the participants’ language choices, the impact of their beliefs on their actions, and the co-construction of common beliefs.

Target Language Use in a SAE

The data showed that different social practices and material conditions such as housing and transportation contributed to reduce the opportunities of contact between the learners and their host. These circumstances worked against the learners’ expectations of improving their L2 proficiency as a result of a constant interaction with English speakers. Lacina (2002) has explained this clash between expectations and reality in cross-cultural experiences based in the distinctive ways in which social networks are constructed and maintained across cultures. Other factors, such as language attitudes in the hosts (Preston, 2004; Rubin, 2001), pragmatic competence deficit in the learners (Gass & Neu, 1996), or social values that are differentially constructed in individual and collectivist societies (Triandis, 2004) certainly have a role in this phenomenon.

Regardless the possible intervening factors, the conditions that emerged as connected to the adjustment of beliefs and actions were the lack of significant relationships with the hosts and the parallel intensification of the interactions with the L1Co. In other words, when the participants’ expectations were not fulfilled, they retreated to the safety of their L1Co. This reaction has been observed before within SAE contexts (Jackson, 2008; Myles & Cheng, 2003) and does have an impact on the learners’ actual L2 gains during a SAE. For these reasons, Yang and Kim (2011) have pointed out that the mere participation in a SAE does not work as a guarantee of important improvements in L2 proficiency unless the learners’ beliefs manage to align with the L2 context. I would add that this alignment is not always possibly given the distance between cultures, the learners’ perceptions of their host’s attitudes (Chik & Benson, 2008), and the transitory nature of the learners’ stay in the target culture (Jackson, 2008). However, the same isolation from the L2Co has also been observed in international students whose stay has been far more extended (Chang, 2011), and even in cases in which immigration into the TLC has been considered as part of the L2 user’s future plans (Ortaçtepe, 2013).

Therefore, concerning the question of whether the participants’ beliefs about the L2 and the TLC changed or not, the data answers this affirmatively. To the second question, regarding the manner in which these changes happened, the analysis suggests that they occurred as the participants interacted with different social groups, namely their hosts and their fellow-country people.

Strategies: From Beliefs to Actions and Back

The analysis also reveals a connection between the participants’ beliefs about the TLC, and their actions, especially L2 avoidance which echoes similar attitudes observed by previous research (Gallagher, 2013, Jackson, 2008). In fact, the three participants experienced the same retreat to L1 in spite of their different L2 learning backgrounds. The case of Silvia is particularly interesting since she reported that in her childhood her L2 was often her preferred language, especially when she talked to her playmates. Twenty years later, however, with her identity as Mexican and as a Spanish speaker firmly consolidated, Silvia chose to index solidarity with her L1Co using Spanish, while she avoided the use of a language whose speakers she perceived as indifferent. This paradox makes one think of the complex and emergent nature of the relationships between beliefs, self-concept, and identity which has been discussed elsewhere (Barcelos, 2000; Mercer, 2011). At the same time, the limited L2 use led participants to believe that their L2 gains had not been as high as expected. In sum, the participants’ beliefs impacted their actions, and these actions also shaped their perceptions and assessments of their L2 improvements. These complex interactions led to sometimes unexpected and paradoxical consequences.

Consequences: The Co-construction of Beliefs and Actions

The confinement of the participants to their L1Co also contributed to nurture common beliefs. Naturally, the participants compared notes with their Mexican peers about their experiences with their hosts. Since their perceptions coincided, the opinion exchange eventually consolidated a shared set of beliefs. So, it could be said that social interaction with peers mediated to establish or reinforce beliefs. In turn, beliefs were materialized as L2 avoidance in spite of the participants’ previous stories of success as L2 learners.

Simultaneously, experiences and beliefs about the TLC impacted interaction with other multilingual L2 speakers. The first L2 interlocutor that the participants seemed to have in mind at first was the native English speaker. However, beyond the classroom, the participants found little opportunities to socialize with their American colleagues. In contrast, the international students who were placed in geographical proximity emerged as the most natural interlocutor with whom they could use English. Although the contact with this group was basically incidental, it eventually led to the emergence of new beliefs about the role of ELF.

Despite this unexpected benefit, a paradox remained: although the participants learned to appreciate the use of ELF, this experience did not lead to an epiphany about its linguistic and social value as opposed to the use of English to communicate with Americans. In the participants’ discourse, the native English speakers remained as the model and the L2 interlocutor par excellence.

Thus, as an expanded answer to the research questions, it can be said that the participants’ beliefs about the target language and its culture were impacted by interactions with different linguistic groups, opening new perspectives about the value and different roles of English. However, even if the SAE exposed the learners to unexpected new beliefs about English, certain aspects of the narrative regarding the ownership of English remained unchanged. This suggests that regardless of its emergent nature, certain beliefs that have been especially nurtured by prevalent cultural views resist change.

In this context, the L2 instruction received during the SAE had a secondary value in the learners’ eyes. Although learners subjectively perceived that their writing skills had improved, one of the aspects most appreciated in Elena and José’s classroom experience was their interaction with peers, not the actual course contents. Apart from this highlight, the course was globally judged as boring and unattractive by the participants. As for Silvia, who navigated alone in a course she perceived beneath her level, the experience was eventually assessed as a “waste of time”. The reason for her negative view is understandable. Instead of acknowledging Silvia’s perceived identity as an effective L2 user, the university assigned her an unwanted identity (that of an L2 learner of inferior proficiency vis-à-vis other members of her L1Co). Seen under this light, Silvia’s resistance to her EAP course seems to echo other cases of failed interactions with instruction among L2 users of different nationalities, ages, and degrees of investment (Barcelos, 2000; Chen, 2010; Cho, 2013, Jackson, 2008).

Conclusions

In this study, I have analyzed learners’ narratives to gain an emic understanding of L2 learners’ beliefs during a SAE. The data suggest that learners socially constructed and adjusted their beliefs as they interacted with different social groups. In this process, different social and material conditions interacted with actions in a dialectical fashion. The data shows that the beliefs about the host culture and the hosts’ attitudes as aloof and impersonal contributed to the retreat of the participants into their small L1Co, as a home away from home. One of the consequences of this action was the avoidance of L2 use. In this context, the contribution of L2 instruction (prior and during the SAE) to help learners cope with the social challenges of L2 use appeared as mostly irrelevant. Actually, the participants were apparently taken aback by the unfamiliar social practices in the host culture. This bewilderment gives us grounds to suspect that such issue was perhaps not addressed in their L2 classrooms. The problem appears as ironic in individuals coming from a non-English speaking country that should be especially familiar with the American culture, given Mexico’s proximity to the United States. This perceived gap in the participants’ second language education should be looked by EFL teachers in Mexico, ESL teachers in the US, and specifically students who plan on participating on exchange programs. Therefore, regardless of the nature of the learners’ native culture, it seems that L2 instruction for learners in SAE should approach topics such as cross-cultural differences and the value of ELF more seriously. As well, students who study in the United States should take risks to talk more with the target language speakers if this is what they would like to do. It seems that these issues should be addressed in order for future exchange students to have a more positive exchange program experience. The question concerning the value of explicit instruction of cross-cultural differences and the role of ELF to achieve more satisfaction in a SAE is an area for future research.

References

Alanen, R. (2006). A sociocultural approach to young language learners' beliefs about language learning. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 55-85). New York: Springer.

Allen, L. (1996). The Evolution of a Learner's Beliefs about Language Learning. (Carlenton Papers in Applied Language Studies Vol. 13). Ottawa: Carlenton University.

Amuzie, G. L., & Winke, P. (2009). Changes in language learning beliefs as a result of study abroad. System, 37, 366-379. doi:10.1016/j.system.2009.02.011

Aragão, R. (2011). Beliefs and emotions in foreign language learning. System, 39, 302-313.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2000). Understanding Teachers' and Students' Language Learning Beliefs in Experience: A Deweyan Approach. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Order No. 9966679)

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2006). Teachers' and students' beliefs within a Deweyan framework: Conflict and influence. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 171-199). New York: Springer.

Bellingham, L. (2005). Is there language acquisition after 40? In P. Benson, & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners' Stories: Difference and Diversity in Language Learning (pp. 56-68). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, Y. J. (2011). Picking one's battles: NNES doctoral students' imagined communities and selections of investment. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 10, 213-230. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2011.598125

Chen, X. (2010). Identity construction and negotiation within and across school communities: The case of one English-as-a-new-language (ENL) Student. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 9, 163-179. doi:10.1080/15348458.2010.486274

Chik, A., & Benson, P. (2008). Frequent flyer: A narrative of overseas study in English. In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. Ferreira (Eds.), Narratives of Learning and Teaching EFL (pp. 155-168). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cho, S. (2013). Disciplinary enculturation experiences of three Korean students in US-based MATESOL Programs. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 12, 136-151.

Cotterall, S. (2005). It's just rules . . . that's all it is at this stage . . .'. In P. Benson, & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners' Stories: Difference and Diversity in Language Learning (pp. 101-118). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gallagher, H. C. (2013). Willingness to communicate and cross-cultural adaptation: L2 communication and acculturative stress as transaction. Applied Linguistics, 34, 53-73.

Gass, S. M., & Neu, J. (Eds.). (1996). Speech Acts across Cultures: Challenges to Communication in a Second Language. Berlin: M. de Gruyter.

Gee, J. P. (2008). Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses. New York: Routledge.

Hosenfeld, C. (2006). Evidence of emergent beliefs of a second language leaner: A diary of study. In P. Kalaja, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 37-54).[E-book version]. Retrieved 24 May, 2015 from: http://www.springer.com/education+%26+language/book/978-1-4020-4750-3

Jackson, J. (2008). Language, Identity, and Study Abroad: Sociocultural Perspectives. London: Equinox Pub.

Jenkins, J. (2012). English as a Lingua Franca from the classroom to the classroom. ELT Journal, 66, 486-494. doi:10.1093/elt/ccs040

Jones, F. R. (1994). The lone language learner: A diary study. System, 22, 441-454.

Kalaja, P. (2006). Research on students' beliefs about SLA within a discursive approach. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 87-108). [E-book version]. Retrieved 24 May, 2015 from: http://www.springer.com/education+%26+language/book/978-1-4020-4750-3

Kalaja, P., Menezes, V. L., & Barcelos, A. M. F. (2008). Narratives of Learning and Teaching EFL. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, A. (1993). French Lessons: A Memoir. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinginger, C., & Farrell-Whitworth, K. (2005). Gender and Emotional Investment in Language Learning during Study Abroad. (CALPER Working Papers Series No. 2). Retrieved 24 may. 2015 from: http://calper.la.psu.edu/publication.php?page=wps2

Lacina, J. G. (2002). Preparing international students for a successful social experience in higher education. New Directions for Higher Education, 2002(117), 21-28. doi: 10.1002/he.43

Lantolf, J. P., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). (S)econd (L) anguage (A)ctivity theory: Understanding second language learners as people. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner Contributions to Language Learning: New Directions in Research (pp. 141-158). London: Pearson Education.

Malcom, D. (2005). An Arabic-speaking English learner's path to autonomy through reading. In P. Benson, & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners' Stories: Difference and Diversity in Language Learning (pp. 69-82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mercer, S., & Ryan, S. (2010). A mindset for EFL: Learners’ beliefs about the role of natural talent. ELT Journal, 64, 436-444. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccp083

Mercer, S. (2011). Language learner self-concept: Complexity, continuity and change. System, 39, 335-346.

Murphey, T., & Carpenter, M. (2008). The seeds of agency in language learning histories In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Narratives of Learning and Teaching EFL