Introduction

Listening comprehension is one of the most neglected skills in English language teaching (Nation & Newton, 2009). It is, as well, a difficult skill that learners must face when learning a foreign language, often because listening activities are designed to make the learner obtain information from an activity (Harmer, 2007), or because of different factors concerning the audio and activity. These factors may be characteristics of the speaker (accent, pronunciation, tone, voice, etc.), the role of the listener, the content of the activity and the aids provided for the activity (Nunan, 1991). These are some factors that make the listening skill both neglected and difficult.

Moreover, listening is only a small part of grades for university students of the BA of English Language at the Universidad Veracruzana. As a result, students have found other sources of exposure to English. One option, as stated by several students, is songs. Nevertheless, songs, although requested and used by students, are not commonly used in classrooms in my context. During a normal weekday class, an estimated fifteen minutes are used for listening exercises, in compliance with both course books and class syllabus. In my opinion this is not enough to provide good listening practice. In this article, I argue that using songs is a viable option for improving listening comprehension. I will discuss how the listening skill may be supported by the use of technological aids which can be used outside of the classroom in a ludic and fun manner using games with songs. To support this idea, this article explains the website LyricsTraining, a game-based activity for songs. Its use is supported by the principle of CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning) in English teaching. To implement this method, participants were invited on-campus and their e-mails obtained. The information acquired was then used to obtain results and insights from the implementation of Lyrics Training.

Literature Review

To understand listening comprehension, it is necessary first to understand the two main processes by which a person deals with information from the source. Harmer (2007) and Richards (1990) mention that the two different processes involved in processing information are bottom-up and top-down. On the one hand, bottom-up relies entirely on all the information being given to the receptor. On the other hand, top-down complements the information given, with embodied information within the subject. In both circumstances, the receptor must process the information and produce a meaning.

In order to obtain the information, one must listen carefully. According to Martin (n.d.), listening comprehension is to be able to interpret a spoken message in a reasonable manner. Listening is not only hearing attentively. Hearing, according to Linse and Nunan (2005), involves only the perception and processing of sounds, not comprehension. For listening to happen, instead of hearing, several aspects should be considered. Ur (1986) mentions that understanding intonation and stress, coping with redundancy and noise, predicting, understanding colloquial vocabulary and understanding different accents improve the chances of obtaining correct information from a message.

Dealing with spoken clues is something that English learners must do when they practice. At least half the time learners spend in contact with a language is through listening (Nation & Newton, 2009). Nevertheless, it is one of the most neglected skills in language teaching, and most teachers take it for granted during their courses (Fang, 2008; Field, 2008; Nation & Newton, 2009). This is especially important when learners are not in a target language environment. Not being in direct contact with the target language outside of the classroom represents for both the teacher and the student a barrier that cannot be overcome easily. While an ESL learner needs to “survive” (Field, 2008, p. 269) outside of the classroom, the EFL learner often stays in a comfortable zone by confronting only examples from the textbook or in the class. A similar situation happens with the teacher, when he/she tries to find meaningful and authentic material for the learners to use. In some cases, finding such material is rather difficult or signifies an arduous task for the teacher (Field, 2008).

For these reasons, it is of the uttermost importance to allow and encourage learners to have more contact with English, even outside of the classroom. One suggested method is by increasing exposure to language in different non-academic scenarios, such as in our cars or with MP3 players with songs (Harmer, 2007). Technology is a way to have more exposure to English.

Computer Assisted Language Learning

According to Davies (n.d.), Computer Assisted Language Learning is “the search for and study of applications of the computer in language teaching and learning” (p.1). The term was coined in 1983 at the TESOL Convention in Toronto, and even when revisions of the term have been suggested, the foundations of CALL remain the same (Chapelle, 2001). Software, or applications, usually falls in one of the two categories for CALL: 1) generic software applications, and 2) CALL software applications. The first are applications which are not designed to teach English, but can be used as such by giving students instructions on what to do, whereas the second category refers to applications created by the author to enhance the learning experience based on his or her beliefs about learning. Web-based CALL is the most recent CALL branch. Internet became available to the general public in 1993 (Davies, n.d.), and this has brought several advantages to CALL.

According to Harmer (2007), a wide variety of recorded materials are now available in formats in formats which computers can play with few problems. Additionally, access to mobile playback devices, such as MP3 and MP4 players, allow more learners to access this material and some material even at no cost.

Implementation of CALL is usually induced by teachers, and in some cases, by learners (O’Donoghue, 2014). However, learners do not always implement CALL without the prior introduction from a teacher. The implementation, therefore, happens usually in academic contexts. In the first steps of CALL, a teacher would take a computer into the classroom and share its use with learners (Davies, Walker, Rendall & Hewer, 2012). This has not changed today, as implementation usually requires the teacher to bring the equipment into the classroom to, at least, show how it is used, so as to allow learners its use in other places.

CALL has a set of advantages that can be exploited when teaching languages. Davies et al. (2012) mention that learners may have unlimited access to resources. Learners may choose the activities they find more attractive or needed at the pace they find more comfortable. CALL also allows the teacher to have more time for non-independent activities, for examples, giving a new grammar topic to learners. Moreover, CALL should be seen as a complement to teacher, not a replacement (Davies et al., 2012).

There are, however, disadvantages that must be considered when using CALL. The main four, as mentioned by Davies et al. (2012) are: 1) motivation from students, 2) technical support, 3) the correct use of resources available for practicing, and 4) the lack of practice with other students, teachers and native speakers. Teachers must also have the proper knowledge to instruct how to use CALL correctly. These factors hinder the implementation of CALL in environments in which “digital skills” (Ramírez & Casillas, 2014, p. 33) are not fully embodied with the actors involved. Additionally, Clark (1994) makes a strong criticism about technology being a remedy for many problems just because people tend to take positive evidence as the only evidence, leaving behind evidence that does not fit the problems. Clark (1994) mentions “we tend to encourage students (and faculty) to begin with educational and instructional solutions to search for problems that can be solved by those solutions” (p. 6). Chapelle (2001) adds that the evaluation of the effectiveness of CALL must be carried out with up-to-date methodologies and based upon the desired outcomes from the implementation. This suggests that careful planning must be performed to introduce CALL in academic contexts (O’Donoghue, 2014).

Methodology

Action research is usually performed when something is being introduced or used in a research study in order to get insights and results from its implementation, and all the process is recorded and used for further improvements (Burns, 2010). This author (2010) also mentions that the central idea of action research is to look directly at a problem being studied in order to bring changes and improvements in practice. This research explores the use of LyricsTraining applied in an academic environment to see if listening can be improved at the Universidad Veracruzana. Bell (2005) mentions the following concerning the context of the problem:

Action research is an approach, which is appropriate in any context when ‘specific knowledge is required for a specific problem in a specific situation, or when a new approach is to be grafted on to an existing system’. […] The aim is ‘to arrive at recommendations for good practice that will tackle a problem or enhance the performance of the organization and individuals through changes to the rules and procedures within which they operate’. (p. 8)

In the next section I will describe the context of this action research.

Research Context

This action research was carried out in the Faculty of Languages of the Universidad Veracruzana. At this school there are three bachelors offered: French Language, English Teaching and English Language. The school has a library, two computer labs, and a self-access center (SAC) equipped with computers, material for language practice and Wi-Fi. Students are required to attend the SAC where students take part in different language activities autonomously for a minimum of hours set by each teacher. Concerning English classes, the school offers classes eight hours a week for six semesters. Listening is not given as much importance as it should at our school and proof of this are the English exams which include a listening section and this section is only worth 10 percent. These exams are taken twice a semester, and oral exams (where listening skill is also important) are given only once a semester. The students’ listening grades flow from .0 to 1.0 from a total of 10.

Participants

Beginning English students enrolled at the Universidad Veracruzana were chosen as the participants because of their level and the fact that their listening comprehension is lower than advanced students. In total there were twenty participants (17 beginners, and 3 pre-intermediate) and they are also students in our BA in English Language. The students were selected, on a random basis, to participate which represents the “target investigation” (Johnson & Bhattacharyya, 2009, p. 10).

Techniques: Questionnaire and Blog

A questionnaire of close and open-ended questions was used as a technique to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The questionnaire was created and answered completely online with the use of Google Docs’ Forms. The questionnaire had 33 items in Spanish aiming to obtain impressions about the use and effectiveness of LyricsTraining. A blog was implemented after using the website Lyricstraining.com. The information needed from the participants was their experience and impressions. Additionally, the blog was used to provide the user’s manual, the links to the exercise, and the questionnaire.

Piloting

I piloted the exercises, questionnaire, and tools such as a blog and links with five participants from the same population in order to solve any problems before the research was carried out. The results of the pilot showed problems such as typos, broken links, and confusing information. As well, official permission was obtained in order to carry out this research.

Website and Preparation for the Study

LyricsTraining Website

LyricsTraining (www.LyricsTraining.com) is a website (Web 2.0) which makes use of material available to language learners (Mills, 2010). Solomon and Schrum (2007) mention that the Web 2.0 are the tools with similarities to a desktop application, with the advantage of not requiring installation on the hard drive to work; instead, the user only needs an internet browser and connection to the world wide web. LyricsTraining mentions that their site is “[…] an easy and fun method to learn and improve your foreign languages skills through the music videos and lyrics of your favorite songs”.It allows the user to play music videos shared on YouTube, along with lyrics transcribed by other LyricsTraining users. The goal of this website is to help people to practice listening with songs and play a game by completing the lyrics of a song. While the user is listening to a song, he or she types the lyrics, gaining points by doing so correctly, and forfeiting the game when too many mistakes have been made. Scores may be saved or users can compete with other users. The user may review words he or she has typed correctly, allowing for continuous revision of spelling.

A user’s manual for the exercises and the website were created to help participants overcome obstacles that might come about during the implementation and to help the users navigate the website. Twelve songs were chosen and recent songs were not used due to the fact that many people would know the lyrics. Often older songs are considered boring or dull. According to Harmer (2007), “the most difficult part of selecting songs for educational purposes is to know what songs are both meaningful and pleasant for students” (p. 320). Therefore, I decided to choose songs from famous, but not mainstream artists, such as Eric Clapton, Sting, and Aerosmith. The songs were also chosen depending on the level of the students, somewhat easy, yet challenging.

Students’ Process of Using the Website

The participants’ e-mails were obtained directly from them, and were needed to inform the participants that the exercises were ready. I tried to stay online in a messenger account to respond to any doubts participants might have had regarding the instructions, the exercises or the questionnaire. Most participants did not have any problems, whereas other required attention that was provided and the problem solved. Some interesting insights were provided, for instance, some participants made comments regarding how these exercises would help them in classes, and other comments on how listening is taught during their English classes. All these comments were added to the data analysis.

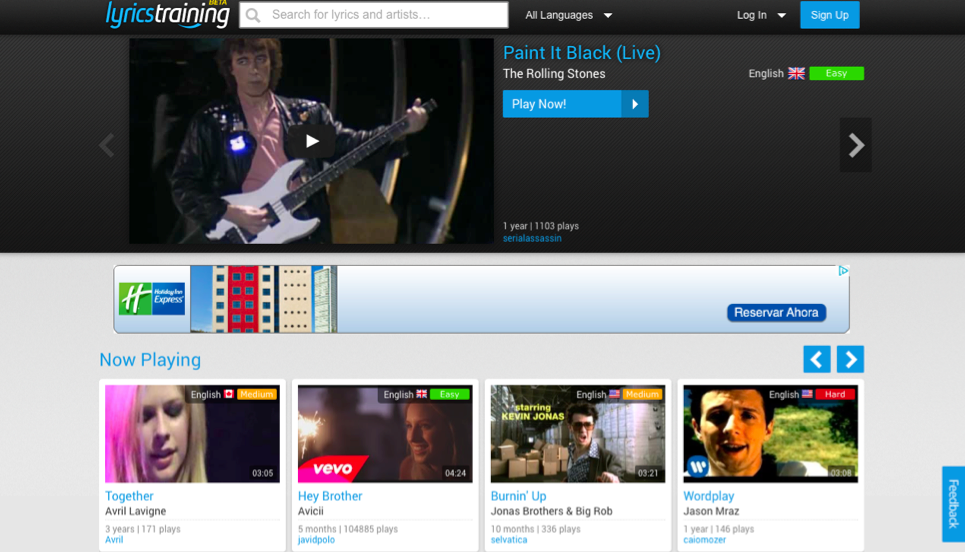

To solve the exercises, participants only needed to open their e-mail accounts to find the links to the website and start solving them. The link directed them to a website which includes a searcher, links to other websites and in-site tools, accounts, as well as new exercises recently uploaded (see Image 1).

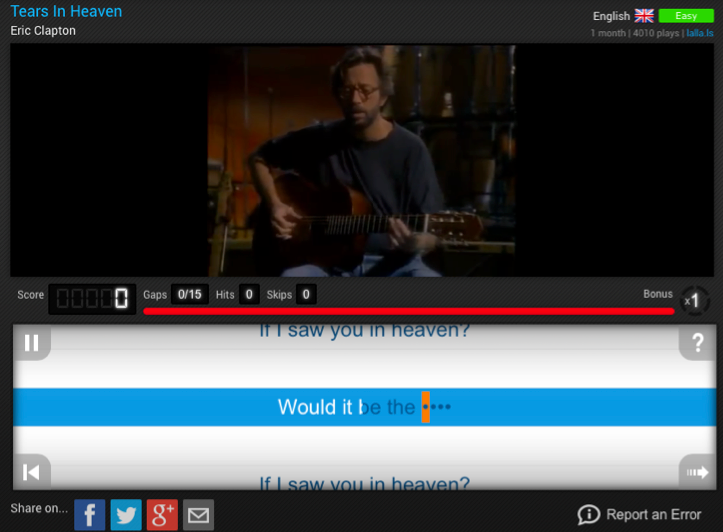

Optionally, clicking on the direct links would take them directly to the songs which needed to be solved. Once there, they had to click on the play button to start the video and activity. Participants needed to fill-in the blank spaces on the lyrics, marked with either circles or asterisks (see Image 2).

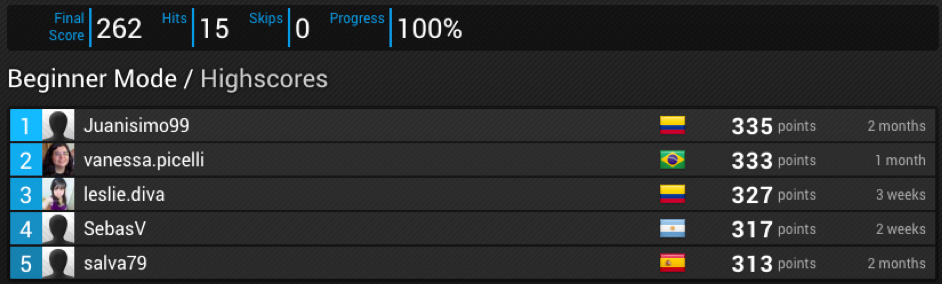

These blank spaces were missing words in the song’s lyrics, which the students had to listen to, and type as the song played. When a key was pushed, and if the letter was right, lyrics on the blank space appeared. If it was wrong, there was no indication of an error and nothing was shown, and the participant needed to type other keys. If during playback the user was not able to provide a correct answer, after each line of active lyrics (highlighted blue in Image 2) the song stopped, but the score timer would run to determine the final score. Both the time and the amount of errors counted towards the final score. The participant then had the choice to re-think his/her answer or to re-play the active lyrics by pushing the backspace key. Once the song was finished, the website showed a total score (see Image 3), which was calculated automatically based on the speed of the answer and penalizing for each second spent without typing a word and that caused the video to auto-stop, as well as each wrong answer.

Once finished, the participant had to click on the questionnaire link to solve it. Internet chat/messenger software was crucial during this research in order to resolve any technical difficulties or questions related to the process of activity solving. The use of this tool was fast and inexpensive communication.

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using a spreadsheet file with all the answers collected from the online questionnaire directly with Google Docs. The results were graphed (33 graphs in total) with the tool ËGraphË from Google Docs. Because some questions were related and could be crossed to double-check information provided, only one representative graph was chosen for some questions to be shown in the final report. This crossing was done to understand the situation of the listening skill and the interferences when trying to comprehend details from a song or a conversation. Open-ended questions were also part of the questionnaire and they gave the participants the opportunity to express their ideas at length.

Data

Advantages

Listening comprehension activities helped students to improve their pronunciation. According to some participants and thanks to the lyrics of a song being played along with the music, they were able to hear what a word sounds like. As a result, they felt they improved their pronunciation by listening to other people’s pronunciation. This is particularly useful when students do not have contact with people other than teachers and students.

Finally, this method in which songs or videos play along with the lyrics as an activity allowed the student to choose from a wide variety of items. This is particularly helpful thanks to the strong motivation the freedom provides. As a result, having a wider range of options to choose from (other than book activities), the student might show more interest in practicing listening, as well as other skills, too. The Internet provides this variety of options, thus creating many activities to carry out.

Limitations Pronunciation, Accent, and Speed of Speech

Some problems seemed to prevent students from listening correctly. One problem might be that participants were not actually at the level they graded themselves. Additionally, participants were beginner and pre-intermediate levels. This can be easily seen in the questionnaire when participants indicated that normal spoken aspects prevented them from understanding clearly. These aspects were: pronunciation, accent, and speed of speech. Participant J stated that the “Auto-stop feature helped me when pronunciation prevented me from listening clearly”. Nevertheless, other participants mentioned that their difficulty to understand was because they did not like the songs. This echoes Harmer’s (2007) idea that when choosing the material to be presented to students it must be interesting for them.

Additionally, half of the participants stated that they reset an exercise at least once. This might be due to a low score, and they might have reset the exercise to improve it. Again, the lack of exposure to English, and different accents, might be the reason why pronunciation was the main deterrent to getting a good result during the exercises. Nevertheless, it is important to mention that not a single participant reported that words were unknown to them. This suggests that participants may have a large lexicon, but might not know how these words, and others sound in a real life context.

Unknown Words and Spelling

Almost half of the participants stated that they had spelling issues. Not having a person to help them when errors appear might be a problem, and prevent them from finishing the exercise. Using a dictionary could easily solve the problem, but it could be time-consuming for a timed activity that penalizes delays. As a result, it seems that not every student is capable of solving exercises without any help. In this case, the autonomy of a student seems to be crucial when using technology. Otherwise, it might be a waste of time.

There seem to be two widely known problems: unawareness of words and spelling errors. Almost half did not know all the words they typed. However, being unaware of the word you are listening to, but being capable of typing it, might show that the listener can listen and comprehend what is being said. Therefore, these exercises might actually help students improve their listening comprehension skill.

On the other hand, there are spelling errors, which create an obstacle in overcoming successfully this listening task. Students might comprehend the word, but might not be able to type it. Almost 50% of the participants claimed that they had spelling errors during the exercises. This suggests that, even though the participants might have good listening comprehension skills, almost half lack the ability to spell correctly. This becomes particularly important when the listening skill is evaluated during an official certification exam (such as TOEFL/Test of English as a Foreign Language or a Cambridge exam), or in the real world, when a person is required to obtain specific details from speech.

Limited Computer or Internet Access

A computer with Internet access is necessary for using this tool. In Mexico, access to both a computer and Internet at home is rather expensive for students. Connectivity in-campus is usually slow and restricted to academic websites, and YouTube is not considered as such by the university. As a result, it is important to provide better access and connectivity policies for all at the university and in society so that they are part of a connected society. Mexico is a country where owning a computer and having Internet access is not possible for everyone. Regarding this, 21% of the participants did not own a computer, nor did they have Internet access. A total of 47% users own a computer and have Internet access at home. However, there is a group of 32% who have either a computer or an Internet connection, but not both. As a result, students often borrow computers from friends and family, or use the obsolete computer equipment often found in schools and universities, or even worse, pay to use computers and Internet connections. This echoes Thelmadatter (2008), who says that students often must spend money to be able to practice.

Discussion of Results

Multimedia Exercises Might Improve Retention of Words

Most participants seemed to be able to remember words after the exercises. Two of the questions focused on seeing if they could remember at least five words at the questionnaire end, which means an estimated ten minutes after the last exercise. Only two participants were unable to remember at least five words. The goal was to know if five words could be stored in their memory after a series of questions about the exercises. This retention might be related to the non-academic approach which resembles more a game than a test. Doing these exercises might have been interesting for students using multimedia materials, thus increasing their concentration levels and retention. White (2010) and Martin (n.d.) emphasize that attention levels increase when a person regards the information as interesting.

Students Request the Use of Movies and TV Shows with a Similar Approach

Students indicated that they were more motivated when using other multimedia materials, such as television shows and movies. Only two considered it more important to have specific vocabulary from an English course book than any other questionnaire option. In addition, not a single participant considered other everyday aspects of communication, such as a conversation on a personal video or TV ads/commercials important. This disregard of such common situations might be related to the lack of amusement that students might have from them.

Exercises Help with Pronunciation

Pronunciation was identified as a problem in listening comprehension; participants considered that these exercises helped them improve their pronunciation. By listening to a song, and reading and typing its lyrics, users stated they had an opportunity to hear how a word is pronounced, whether they knew its meaning or not. For example, Participant B stated: “They (the exercises) allow us to identify our pronunciation mistakes”, while Participant D stated: “It (the use of multimedia) helps us to understand the language faster”. In addition, Participant M mentioned that these exercises helped him/her to stay in contact with real English, which does not usually happen during classes. This last comment echoes White’s (2010), when he mentioned that exposure to English does not happen often during classes.

Contrary to these comments, some considered that pronunciation was a problem when listening to the songs. In addition, Participant B considered that when a blank space appeared, he/she became nervous because he/she might be losing points for his/her final score if he/she mistyped the word. Perhaps this person is trying to save face. Listening comprehension might be affected by the users’ ability to control their nervousness. This nervousness might be related to the approach the listening activities have during classes, when the student must obtain the right answer, otherwise he/she would fail to answer correctly in that specific blank space (White, 2010).

Helpful Video Stop Instead of Continuous Play

Related to the participants’ problems of listening clearly is the pressure of time. As mentioned by White (2010), when people have no opportunity to negotiate meaning during a conversation, they become nervous. Unfortunately, negotiating meaning in a listening activity is not possible. An example is a movie in a movie, when the spectator has only one opportunity to understand what the actors say. If something is missed, the moviegoer cannot replay the scene. The same thing happens during the use of multimedia in TEFL. This extra pressure of time makes students nervous. In contrast, LyricsTrainingincludes a playback ‘lock’. When a user does not type a word, the video automatically stops, so the user has more time to rethink his/her answer before the audio keeps playing. This reduces pressure. Participants considered this built-in feature as the most important feature of the website. This might show us how important it is for language learners to be able to negotiate meaning, instead of being “passive overhearers” (White, 2010, p. 6), or at least have tools, such as rewinding, that allows them to think clearly without the pressure of time. For example, Participant B stated “I used it two or three times, and it is important, as trying to remember what was just said is harder if sound keeps playing, and that makes us nervous knowing that we may be losing points”.

Social Networking Is Not Important for Their Academic Lives

In spite of the importance of social networking, students might not consider them important for their academic lives. Not a single participant used the options of “share”, “comment”, or “liked” found on Facebook website. Neither did the participants recommend the website LyricsTrainingto their friends or family. LyricsTrainingincludes social networking links, which allow users from social networks to share the link with followers and friends, comment on the website’s “Facebook wall” (section of your profile in which others can write messages to you), “like” the website or just tweet (post on social networking website Twitter) the link. This might be due to the academic approach of the website or perhaps, they do not like sharing school-related links or websites with friends and family. Social networking websites only play important socialroles, not perhaps not in academic contexts.

Conclusions

The students seemed to have a positive attitude when they used the LyricsTraining website. They appeared to have accepted it as a tool to improve their listening and even suggested changes as well as positive and negative feedback on it use. This feedback may show a partial acceptance of this website, and more expectations from its use. Nonetheless, the implementation of websites, such as LyricsTraining, is limited by the teachers and the school’s services and infrastructure. However, any student with a computer and Internet connection may be able to access a new and vast repertoire of tools.The use of songs seems to help students to retain more information. This may be possible thanks to the use of songs as a tool for practicing the listening skill. As a result, song use in classes might be helpful for students to remember grammar structures, words, or phrases presented in song. This implementation, however, needs to be in agreement with the school’s language program. Nevertheless, students are free to practice outside the classroom.

The participants mentioned that pronunciation, speed of speech and accent are important whenever students practice listening using songs and they emphasized that these aspects may hinder their ability to understand the songs. Pronunciation is practiced during exercises, even though the participants stated that pronunciation prevented them from understanding clearly what was being heard. As a result, the pronunciation of words could be improved while carrying out the exercises. One of the objectives of this research was to show how technology could be applied to improve TEFL, and this objective was reached in classes and outside of classes.

Nevertheless, this technique has some limitations. For instance, the school budget may be insufficient, the capacity of teachers to use technology meaningfully may not be high, and students’ acceptance to work with these websites could not be 100%. Also, the students’ ability to use the website correctly, and the access they have to these tools must be taken into account. This free website requires nothing more than a computer and Internet access. Users do not need to pay to access these websites which is an advantage, as most paid software is expensive or difficult to obtain. Therefore, the implementation of websites such as this one is reasonable, as long as teachers and students work together to use them. Thanks to the implementation, analysis, and the participants’ opinions of LyricsTraining, I can conclude that this websiteis an effective tool for students to improve their listening.

References

Bell, J. (2005). Doing Your Research Project A Guide for First-time Researchers in Education, Health and Social Science. London: Open University Press.

Burns, A. (2009). Doing Action Research in English Language Teaching A Guide for Practitioners. (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Chapelle, C. (2001) Computer Applications in Second Language Acquisition Foundations for Teaching, Testing and Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, R.E. (1994). Media will never influence learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(2), 21-29.

Davies, G., (N.D.). CALL (Computer assisted language learning). Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from https://www.llas.ac.uk/resources/gpg/61.

Davies, G., Walker R., Rendall H. & Hewer S. (2012). ICT4LT Module 4.0 Introduction to Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL). Information and Communications Technology for Language Teachers (ICT4LT). Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://www.ict4lt.org/en/en_mod1-4.htm#whatiscall.

Fang, XU. (2008). Listening comprehension in EFL teaching, US-China Foreign Language, 6 (1), 21-29. Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://de.slideshare.net/mora-deyanira/listening-comprehension-in-efl-teaching.

Field, J. (2009). Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google. (2015). Google Docs Support Page. Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from https://support.google.com/docs/?hl=en#topic=1360904, http://goo.gl/cGyyM .

Harmer, J. (2007). The Practice of English Language Teaching. Harlow: Longman.

Nation, I.S. P. & Newton, J. (2008). Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. New York: Routledge.

Johnson, R. A., & Bhattacharyya, G. K. (2009). Statistics: Principles and Methods. John Wiley and Sons.

Linse, C. & Nunan, D. (2005). Practical English Language Teaching: Young Learners. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lyrics Training (2014). About Lyrics Training. Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://lyricstraining.com/abouthttp://lyricstraining.com/about

Martin, E. (1991). La didáctica de la comprensión auditiva. Cable, 8, 16-26. Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://blogs.uab.cat/gloria/files/2012/02/didacticacomprension_auditiva.pdf

Mills, D. J. (2010). LyricsTraining.com. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 14, 2. Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://www.tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej54/m3.pdf.

Nunan, D. (1991). Language Teaching Methodology. A Textbook for Teachers. New York: Prentice Hall.

O’Donoghue, M. (2014). Producing Video for Teaching and Learning. Planning and Collaboration. New York: Routledge.

Ramírez, A. & Casillas, M.A. (2014). Háblame de TIC. Córdoba, Argentina: Brujas.

Richards, J.C. (1990). The Language Teaching Matrix. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Solomon, G. & Schrum, L. (2007). Web 2.0: New Tools, New Schools. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Thelmadatter, L. (2008). Becoming a part of a “community” online in order to acquire language skills, MEXTESOL Journal, 32(1). Retrieved on June 10, 2015 from http://mextesol.net/journal/file/galleys_28

Ur, P. (1986), Teaching Listening Comprehension. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

White, G. (2010). Listening. Oxford: Oxford University Press.