Introduction

Metadiscourse is a concept defined as “the writer’s reference to the text, the writer, or the reader and enables the analyst to see how the writer chooses to handle interpretive processes as opposed to statements relating to the world” (Hyland & Tse, 2004, p. 167). It contains varied classes of resources, the roles of which are to ease the processes of interaction between a writer, his/her text, and those who read it (Hyland, 2010). Mauranen (1993a) says metadiscourse – or as she calls it, metatext – contributes to the organization of the text and gives the writer the opportunity to comment on the propositional sense of the writing. She argues that via metadiscourse “the writer steps in explicitly to make his or her own presence felt in the text, to give guidance to the readers with respect to how the text is organized, what functions different parts of it have, and what the author’s attitudes to the propositions are” (p. 9).

Metadiscourse mainly contributes to the intelligibility of wide-ranging discourses such as academic writings and news articles. It grants the writer the opportunity to interact with the reader, and as Hyland (2005) puts it, it is “used to negotiate interactional meanings in a text, assisting the writer (or speaker) to express a viewpoint and engage with readers as members of a particular community” (p. 37).

Metadiscourse is an element which can contribute to both the organization and the meaning of a text. Therefore, it may seem necessary for a second language learner who wishes to improve his/her writing skills to become acquainted with metadiscourse and be able to accurately utilize it in their writing. Accordingly, the present study aims to explicitly teach EFL learners to employ metadiscourse resources (e.g. conjunctions, hedges, etc.) – from the interpersonal model proposed by Hyland (2010) – in their written discourse to observe whether their writing skills improve. The main reason for adopting Hyland’s model was because it is a comprehensive model which explicates both the textual and interpersonal functions of a text (Hyland & Tse, 2004).

The urge for the current study sparked after the researcher collected some 200 writing samples of EFL learners who were studying at intermediate and upper-intermediate levels at an English institute. The writings were collected as part of the institute’s quarterly policy to evaluate intermediate and upper intermediate level learners through a series of writing and speaking tests. As one of the two raters/interviewers of the tests, the researcher evaluated all the writing samples and found that in nearly 81% of the cases, the writings had been rated ‘poorly organized’, ‘incoherent’, or simply ‘poor’. Likewise, in those cases, the learners had barely used any metadiscourse resources in their texts – except for the recurrent uses of common terms such as ‘and’ and ‘but’. In 15% of the cases, learners had included few conjunctions; and only 4% of the learners, who were rated ‘good’, had properly used metadiscourse tools in their texts. The poor performance of most of the learners on the writing test was mostly due to poor organization of their writing as well as lack of cohesion or coherence. This led the researcher to assume that maybe making learners familiar with the principles of essay writing as well as teaching them metadiscourse could help them perform better on a writing test. Thus, the following question was posed:

Q: Does teaching metadiscourse resources to intermediate EFL learners help improve their writing skills?

Based on the research question, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H: Teaching metadiscourse resources to intermediate EFL learners helps improve their writing skills.

What is metadiscourse?

Hyland defines metadiscourse as “the linguistic resources used to organize a discourse or the writer’s stance towards either its content or the reader” (2000; cited in Hyland &Tse, 2004, p. 157). This definition is based on the view that writing is “a social and communicative engagement between writer and reader” (Hyland & Tse, 2004, p. 156). In fact, writers, via metadiscourse, are able to present themselves in their texts to “signal their attitude towards both the content and the audience of the text” (p. 156).

Metadiscourse, however, is a concept that, since its emergence, has gone through various names and definitions. Some scholars have called it ‘metatext’ or even ‘metalanguage’ and defined it as discourse about discourse (Mauranen, 1993b; Rahman, 2004; Kopple, 1985). It traditionally has been known through the work of Kopple (1985) who believes that metadiscourse is a concept that does not add to the factual meaning or propositional content of the text, but only establishes a connection between the writer and the reader. Williams (1981 ), similarly, argues that it is “whatever does not refer to the subject matter being addressed” (p. 226). Kopple (1985) establishes a framework which classifies metadiscourse into two categories of textual and interpersonal. Textual metadiscourse contributes to the cohesion and coherence of the discourse and interpersonal metadiscourse enables the writers to project their attitude toward the propositional content of the discourse (Kopple, 1985). This framework is based on a “traditional interpretation of textual functions which focuses on language used by writers to comment on or to organize the propositional content” (Tan, Swee & Abdullah, 2012, p. 1). In fact, Kopple (1985, 2002) argues that there are different levels of meaning and distinguishes metadiscourse from the propositional meaning.

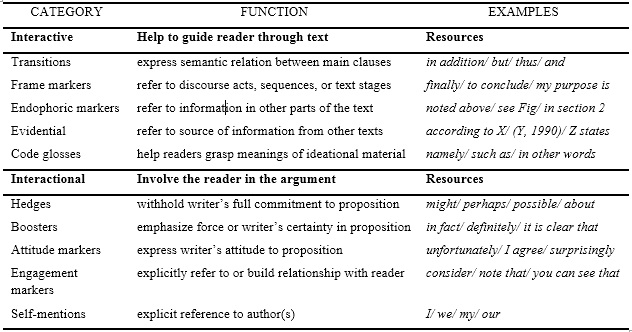

Through the passage of time, the views toward metadiscourse have been broadened and, thus, the definitions were renewed and the frameworks were accordingly upgraded. Hyland and Tse (2004) believe that the distinction between metadiscourse and propositions is not clear-cut and that metadiscourse should not be treated as secondary to the meaning of discourse and to the propositional content. They further point out that metadiscourse is “the means by which propositional content is made coherent, intelligible, and persuasive to a particular audience” (Hyland & Tse, 2004, p. 161). Hyland (2010) argues that metadiscourse provides writers with “means of conceptualizing communication as social engagement” (p. 127). In essence, it makes it possible for a writer to insert – and reveal – his or her “attitude toward both the content and the audience of the text” (Hyland & Tse, 2004, p. 156). In fact, writing is a social concept that establishes interactions between the writer and the reader. Therefore, “academic writers do not simply produce texts that plausibly represent an external reality, but use language to offer a credible representation of themselves and their work, and to acknowledge and negotiate socials relations with readers” (Hyland, 2010, p. 127). Hyland (2010), based on his definition of metadiscourse, proposes an interpersonal model of metadiscourse which is composed of two categories of interactive and interactional resources. The interactivere sources aid the reader to interact with the text and “allow the writer to manage the information flow to explicitly establish his or her preferred interactions” (Hyland, 2010, p. 129). Interactive metadiscourse is comprised of several resources, the first of which being transitions. Transitional markers contribute to cohesion in a text and explicate or clarify semantic relations between statements through a range of markers such as ‘moreover’, ‘in addition’, ‘similarly’, ‘however’, and ‘consequently’. The second type of interactive metadiscourse resources is frame markers, which are responsible for organizing texts for readers by sequencing, stating discourse goals, and marking topic shifts. Terms such as ‘first’, ‘second’, ‘in regard to’, ‘in summary’, and ‘aim to’ are among frame markers. Endophoric markers are the third type of interactive metadiscourse resources, and are often defined as expressions or phrases that refer or point to other parts of the text. Some examples of endophoric markers include ‘as we shall see in the next chapter’, ‘see table 2’ and ‘as I noted earlier’ (Wei, Zhou &Gong, 2016). The fourth type of interactive resources used in Hyland’s model is evidential markers. These tools refer to or present information from other texts through citations and references such as ‘X argues that’ and ‘as Y puts is’. Code glosses, as the final type of interactive resources, are mainly tasked with clarifying the writer’s communicative purpose and explaining propositional meanings through terms such as ‘for example’, ‘such as’ and‘in other words’ (Hyland, 2007; Wei et al., 2016).

On the other hand, interactional resources illuminate the writer’s attitude toward the content of the discourse and provide the writer with the opportunity to establish a relationship with the reader. These devices also “focus on the participants of the interaction and seek to display the writer’s persona and a tenor consistent with the norms of the disciplinary community” (Hyland, 2010, p. 129). Hedges are the first type of interactional metadiscourse. They are used to indicate the writer’s reluctance to present propositional information in the text (Hyland, 2010). According to Wei et al. (2016), hedges are shown through such lexico-grammatical forms as epistemic modal verbs (e.g., could, may), lexical verbs (e.g., suggest, claim), adjectives and adverbs (e.g., probably, perhaps), nouns (e.g., possibility), and other linguistic expressions for marking qualification (e.g., in general, to some extent). The second type of interactional resources is boosters, which, contrary to hedges, are used to highlight the writer’s certainty in propositions. Expressions including ‘must’, ‘undoubtedly’, ‘in fact’, and ‘certainty’ are some examples of boosters. Another marker used in discourse is the attitude marker. Such a tool expresses the writer’s attitude to propositional information through terms such as ‘desirable’, unfortunately’, ‘interestingly’, and ‘what is important’ (Wei et al., 2016). Engagement markers, which are used to explicitly address or build relationship with readers, are the fourth type of interactional metadiscourse. Some examples of engagement markers include ‘as you can see’, ‘keep in mind that’ and ‘remember that’. The final category of interactional tools is called self-mentions. Such resources indicate the presence of the author or authors through terms such as ‘we’, ‘I’, ‘my’, and ‘the present author’.

This interpersonal model of metadiscourse was chosen for the current study to make learners familiar with the resources and guide them how to use these devices properly in their written discourses in order to be able to enhance the cohesion of the texts and develop more reader-friendly discourses.

Hyland’s interpersonal model of metadiscourse (2010) is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Hyland’s model of metadiscourse in academic texts.

A large number of studies have been conducted in the area of metadiscourse over the past years (see Crismore & Abdollahzade, 2010; Hyland, 1998, 2000, 2004, 2010; Ismail, 2012; Le, 2004). Some researchers have explored the role of metadiscourse in journalistic texts (see Abdollahzadeh, 2007; Moghadam, 2017; Kuhi & Mojood, 2014; Le, 2004), and a number of others have studied metadiscourse in various genres of written texts such as research articles (see Abdi, 2009; Siami & Abdi, 2012). Moreover, there have been studies which focused on political discourse (Ismail, 2012), emails (Jensen, 2009), and advertisements (Fuertes-Olivera, Velasco-Sacristán, Arribas-Bano & Samiengo-Fernández, 2001). Various studies have also been carried out on learners’ writing (see Crismore, Markkanen and Steffensen, 1993; Steffensen & Cheng, 1996).

Skimming through the history of metadiscourse and the research conducted in this area, it can be seen that many research articles focus on text analysis and corpus studies. There have also been a number of studies which brought metadiscourse markers into second or foreign language classrooms in a bid to assist EFL learners in organizing and improving their writing skills by training learners how to employ metadiscourse when producing language. Vahid Dastjerdi and Shirzad (2010) as well as Taghizadeh and Tajabadi (2013) have conducted experimental studies to assess the effect of instruction of metadiscourse markers on writing performance of learners. In these two studies, however, the authors did not teach writing skills to the participants and only focused on the instruction of metadiscourse markers. They finally concluded that teaching metadiscourse resources to students can indeed lead to a better writing performance on the part of the learners. In another study, Tavakoli, Bahrami, and Amirian (2012) investigated the development of “interactive metadiscourse resources in terms of appropriacy during a process- based writing course” by providing feedback to learners as they were drafting, revising, and editing their writings (p. 129). Steffensen and Cheng (1996) showed that EFL learners wrote significantly better texts after they were taught how to use metadiscourse. According to Tavakoli, Dabaghi and Khorvash (2010), after learning metadiscourse, students were able to comprehend English texts more easily. In addition, as Ahour and Maleki (2014) found in their study, teaching metadiscourse can enhance learners’ ability in a controlled speaking test.

The current study is an experimental research which focuses on the process of teaching and learning writing. It tries to integrate metadiscourse into the syllabus of a writing course in order to examine whether learners can improve their writing skills.

Methods

Participants

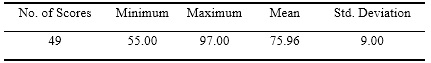

This study was conducted as part of an “Academic Writing Course” at LOBAB English Institute in Iran’s capital, Tehran. The sample of this study was comprised of 38 EFL learners from this Institute, including 25 females and 13 males, all aged between 14 and 44. Prior to the selection of the sample, however, 49 students had volunteered to partake in the course. In order to select a homogeneous sample from all the volunteers, a Cambridge’s Preliminary English Test (PET) was administered. The descriptive data of this test is presented in Table 2:

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of participants’ scores on PET test.

The lowest and highest possible scores were ‘0’ and ‘100’ respectively. As illustrated in the table above, the mean score is 75.96, and the standard deviation is nine. Thus, the scores that did not fall between one standard deviation below or above the mean (i.e., 66.96 and 84.96) were ruled out from the study as outliers. Thus, 11 volunteers were excluded.

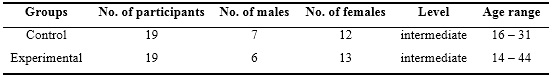

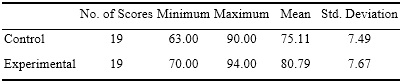

After that, the remaining participants were randomly divided into two groups of control and experimental. However, to ensure that each group contained participants of both genders, male and female learners were separately, and randomly, divided, resulting in two groups of 19. The basic information about each group is summarized in the table below:

Table 3. Basic data about the sample.

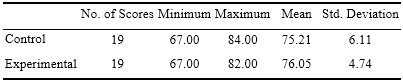

The descriptive data of each group of the study is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of PET test.

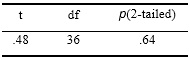

In order to calculate whether or not the difference between the mean scores of the two groups was statistically significant, an independent-samples t-test was carried out (see Table 5).

Table 5. Independent t-test of PET.

After calculating the t-test, the Levene’s test gave a significance level of 0.092, meaning there was no significant difference between variances. Therefore, equal variances between the two groups was assumed for the t-test. As illustrated in Table 5, the probability figure is larger than 0.05 (that is 0.64), indicating that there is no statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups.

Procedure

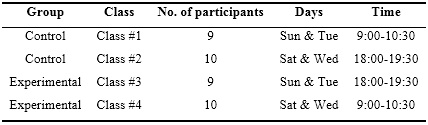

The purpose of this study is to examine whether explicit teaching of metadiscourse resources to intermediate EFL learners can enhance their writing skills. To this end, the author inaugurated a course dubbed “Academic Writing Course”, in which only intermediate learners were allowed to partake. After the selection of the sample and the two groups of the study, the researcher divided each group into two classes to ensure that the classes of the study were less crowded and thus the participants had more time to practice. The table below provides information about each class:

Table 6. Class information

After the classes were specified, the next step was to administer the pre-test (see Appendix A) in order to collect data to quantify the current level of proficiency of the sample regarding their writing skills. This test was composed of two tasks. Task A, similar to the first task in an IELTS general test, asked the learners to write a letter. The second task, similar to the essay task in a TOEFL iBT test, required the participants to write a complete essay. Both tasks in each test were designed to measure the writing abilities of the learners in a similar fashion as a standard international test such as IELTS and TOEFL.

In order to ensure the inter-rater reliability of the scores, three raters – who were all English teachers from another institute – were assigned to evaluate the test papers (see Appendix B for the assessment criteria). As for the assessment rubric, the researcher decided to develop a template based on a set of criteria already used in standardized tests such as IELTS and TOEFL. To do so, six items – namely ‘answer to question (relevance)’, ‘comprehensibility’, ‘organization (paragraphing)’, ‘flow of ideas’, ‘grammar’, and ‘vocabulary’ – were taken from the scoring criteria of the writing task of the TOEFL test (Phillips, 2007). This rubric was expected to evaluate the participants’ writings to measure the extent to which their responses are to-the-point and relevant to the topic, and whether they digressed or not (relevance). It was also intended to measure whether the writings were intelligible or easy to understand (comprehensibility), well-organized and well-developed across paragraphs (paragraphing), fluent (flow of ideas), accurate (grammar), and with appropriate jargon and diction (vocabulary). In addition to the aforementioned items, ‘cohesion’ and ‘coherence’ were added from the scoring criteria of the writing task of the IELTS test (Cullen et al., 2014). While cohesion is usually defined as the interconnection of two different sentences and whether these sentences are related to each other, coherence is known as the logical arrangement of the writer’s ideas in forming paragraphs and structuring the essay. In order to make the assessment criteria more comprehensive, the researcher also added ‘appropriacy’ and ‘reasoning’ items to the template to measure the appropriate style (informal, formal or academic style) of the writer as well as his or her ability to develop logical, creative and well-formed statements to support their main ideas.

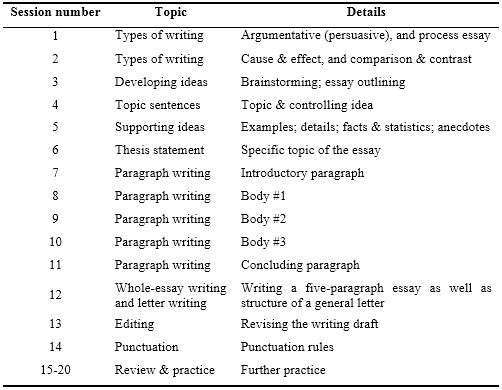

After the learners took the pre-test, they participated in the ‘Academic Writing Course’. The whole course lasted twenty sessions (ten weeks), during which time the researcher himself was the teacher. In fact, to reduce the practice effects, the study period was kept as short as possible so that chances of interference of outside variables such as maturity of the participants were minimized. The syllabus for all four classes (see Table 7) was similar, except for the addition of the metadiscourse resources (introduced in Table 1) in the experimental group (see Table 8). Table 7 shows what was taught in all the classes during each session. The procedure, which was the same for all the classes, was as follows:

Table 7. Syllabus of the course which is the same for all four classes.

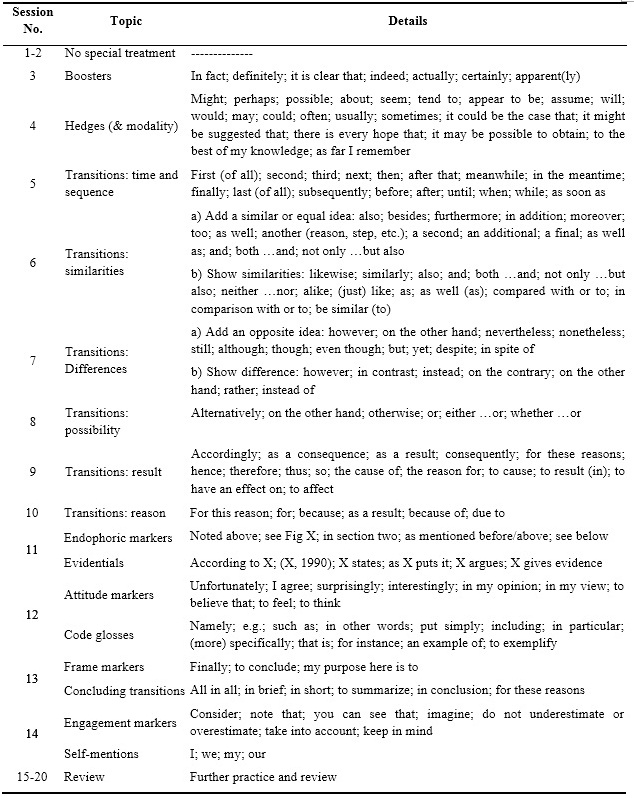

In addition to the syllabus mentioned above, the following table shows metadiscourse resources which were only practiced in the experimental classes:

Table 8. Lesson plan of experimental group.

As shown in Tables 7 and 8, all the four classes spent the first two sessions learning and practicing different types of essay writing. At this stage, the researcher made the learners familiar with argumentative (persuasive), cause & effect, comparison & contrast, and process essays, and the classes had the chance to discuss and practice the basics of each writing type. By the beginning of the third session, the actual treatment began. Here, the control group (i.e., classes 1 and 2) was taught how to develop a topic through brainstorming and then outlining ideas. Then, both classes spent the whole session practicing the lesson with various essay topics. Similarly, the experimental group (i.e., classes 3 and 4) received the same training, but only for 60 minutes. For the next 30 minutes, the participants in these two classes had the opportunity to receive treatment in metadiscourse tools. Here, the researcher taught ‘boosters’ (see Table 1) to the learners and the class practiced the item in sentences or clauses. The next 11 sessions had a similar format; that is, the control group spent a whole session learning items presented in Table 7, while the experimental group, in addition to that, received special training in metadiscourse tools. So, although the experimental group received a special training in addition to the control group, the duration of each class was the same among the groups. At the end of each session, all the participants were given homework assignments and were asked to practice what they had learned at home. Sessions 15 to 20 were also allocated to practicing what learners had learned throughout the course. At the end of the experiment, a post-test (see Appendix C) parallel to the pre-test was administered to calculate any probable improvement of the participants.

Results

Pre-test

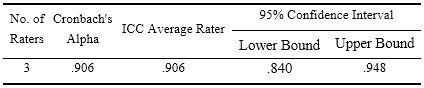

After the selection of the participants and the formation of the groups, the pre-test was administered. It was later evaluated by three raters. The next step was to use Cronbach’s alpha as well as the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of the ratings to measure the inter-rater reliability (Bachman 1990; Crocker & Algina, 1986; Cronbach, 1951; Ebel 1979; Stemler 2004). The result is given in Table 9.

Table 9. Inter-rater reliability of pre-test.

ICC estimates and their 95% confident intervals were measured based on a mean-rating (k = 3), consistency, two-way random model. According to Cicchetti (1994), an ICC value higher than 0.75 and a coefficient alpha higher than 0.90 are considered excellent. Thus, as the inter-rater reliability of the pre-test was satisfactory (i.e., 0.906), the average score of the three ratings was used as the score of the participants. Then, the data gained from the pre-test were analyzed. The following table shows the descriptive data about their performance on this test:

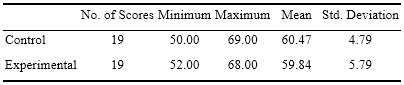

Table 10. Descriptive statistics of the pre-test.

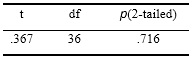

As is shown in the table above, there is no conspicuous difference between the mean scores of the two groups. To objectify our claim, however, an independent-samples t-test was conducted:

Table 11. Independent-samples t-test of pre-test.

The Levene’s test gives the significance level of 0.170, which means there is no significant difference between variances. Hence, equal variances between the two groups should be assumed for the t-test. As the results of the t-test shows, the probability figure is larger than 0.05 (that is 0.716). Ergo, the difference between the mean scores of the two groups has not reached statistical significance. Put simply, there is no considerable difference between the means of the two groups of the study at this stage.

Post-test

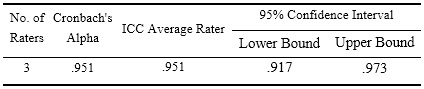

After the treatment, the post-test was administered, the results of which were evaluated by three raters – the same raters who had evaluated the pre-test (see appendix B for assessment criteria). The following table shows the correlation of the ratings of the raters:

Table 12. Inter-rater reliability of post-test.

Similar to the pre-test, the inter-rater reliability of the post-test was calculated based on a mean-rating (k = 3), consistency, two-way random model. As mentioned above, an ICC value higher than 0.75 and a coefficient alpha higher than 0.90 are considered excellent. Thus, the inter-rater reliability of the post-test (0.951) was deemed high (Table 12), and, in a similar fashion to the pre-test, the average of the three ratings was calculated to be the score of the participants of this test. Next, the descriptive statistics of the results of the post-test for both groups were calculated:

Table 13. Descriptive statistics of the post-test.

As it is illustrated above, the mean score of the control group in the post-test is 75.11, which, compared to the same score on the pre-test (i.e., 60.47), shows a 14.64-point increase in the performance of the participants. The mean score of the experimental group on the post-test is 80.79, which, in comparison with the same score on pre-test (i.e., 59.84), indicates an increase by 20.95 points. The following table shows the descriptive data of the control group on pre- and post-tests:

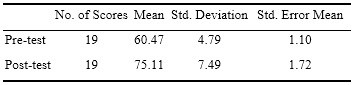

Table 14. Descriptive statistics of control group on pre-/post-tests.

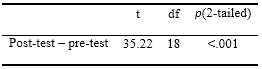

The table above shows that the mean score for the control group on the pre-test is 60.47, and on the post-test is 75.11. The standard deviation for the pre-test is 4.79 and for the post-test is 7.49. In order to find out whether the difference between the mean scores on the pre-test and post-test are significant, a paired-samples t-test was conducted:

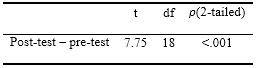

Table 15. Paired-samples t-test of control group

The p-value (2-Tailed) in the table above is less than .001, meaning there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the control group before and after the study. According to the results of the paired-samples t-test, the performance of the participants in the control group improved after the study, which indicates that the classes that they attended had a positive effect on the development of their writing skills.

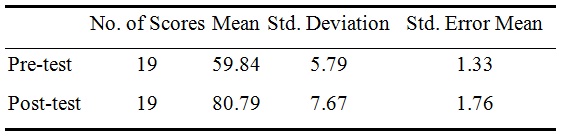

The following table shows the descriptive data of the experimental group on pre- and post-tests:

Table 16. Descriptive statistics of experimental group on pre-/post-test.

As shown in Table 16, the mean score of the control group on the pre-test is 59.84, and on the post-test is 80.79. The standard deviation for the pre-test is 5.79 and for the post-test is 7.67. To see whether the difference between the mean scores of the two groups on the pre- and post-tests is significant, a paired-samples t-test was carried out.

Table 17. Paired t-test of experimental group.

As the p-value (2-Tailed) in Table 17 is less than .001, it can be concluded that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the experimental group-before and after the study. The finding shows that the participants in the experimental group performed better after the treatment. According to the results of the paired-samples t-tests, both control and experimental groups made statistically significant improvements after the treatment.

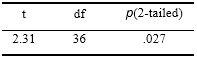

Now, in order to calculate whether or not the difference between the mean scores of the two groups of the study on the post-test was significant, an independent-samples t-test was conducted. The Table below illustrates the result of the t-test:

Table 18. Independent t-test of post-test.

Since the p-value of Levene’s test is 0.654, it can be assumed that the variances of the two groups are the same. Moreover, the probability figure is 0.027, which is smaller than 0.05. So, it can be concluded that there is a significant difference between the mean post-test scores of experimental and control groups. This means that after the treatment, the experimental group outperformed the control group in the writing test. Thus, it can be concluded that the writing skills of the learners who received the special treatment on metadiscourse improved more than those who did not receive any. Therefore, the research hypothesis is supported, meaning the ‘explicit teaching of metadiscourse resources’ did have a positive effect on the ‘improvement of writing skills of EFL learners’.

Effect size

Effect size is a measure which is used to “determine the magnitude of an observed relationship or effect” (Mackey & Gass, 2005, p. 355), and shows the strength of the findings of the study (Dörnyei, 2007; Mackey & Gass, 2005). According to Ellis (2000), it helps in the assessment of “the stability of research across samples, operationalizations, designs, and analyses” (p. xii). It can also pave the way for “evaluation of the practical relevance of the research outcomes” (Ellis 2000, p. xii). As Mackey and Gass (2005) put it, effect size allows “comparison across a range of different studies with different sample sizes” (p. 283). The magnitude of the effect is usually calculated through a number of measures, including eta-squared, Cohen’s d, and Kendall’s W (Dörnyei, 2007).

Cohen’s d formula (Cohen, 1969) is widely used to calculate the effect size in L2 research. Nonetheless, Cohen only provides a general interpretation – not a field-specific one – of d values. An effect size of 0.2 is generally regarded as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large (Coe, 2002; Cohen, 1969; Mackey & Gass, 2007). However, Plonsky and Oswald (2014) have introduced an interpretation of the magnitude of the effect size values which is specific to L2 research. According to Plonsky and Oswald (2014), in L2 research, when it comes to mean differences between two groups, an effect size of 0.40 is regarded as small, 0.70 as medium, and 1.00 as large. In addition, when it comes to within-group differences, an effect size of 0.60 is regarded as small, 1.00 as medium, and 1.40 as large. In the current study, Cohen’s d formula is used to calculate the effect size values, which are then interpreted as Plonsky and Oswald (2014) suggested.

Effect size of within-group differences

According to the results of the paired-samples t-tests, both groups of the study showed significant improvements after two months of participating in the “Academic Writing Course”. The effect size of each of the groups has been separately calculated using Cohen's d formula. Accordingly, the d value of control group on pre- and post-tests is 3.06 and that of the experimental group is 3.62. Both effect sizes are large; however, the experimental group managed to gain a larger effect size.

Effect size of between-group differences

So far, it has been learned that the difference between the mean scores of the two groups of the study on the post-test is significant. However, to assess the magnitude of the finding, the effect size was calculated. To do so, Cohen’s d formula was used, which led to the effect size of approximately 0.75for mean differences between the control and experimental groups in the post-test. Coe (2002) argues that “an effect size is exactly equivalent to a Z-score of a standard Normal distribution” (p. 3). Thus, an effect size of 0.75 means that the score of the average person in the experimental group is “0.75 standard deviations” above the score of the average person in the control group.

To find the probability values for different Z-scores, one can refer to “Table A” forStandard Normal Probabilities introduced in Moore and McCabe (1993). For the current effect size, the probability value is found to be equal to 0.7734. Hence, the average student of the experimental group has a score higher than 77.34 percent of all the students in the control group.

Finally, due to the significance of the difference of the means of the two groups and owing to the effect size of the finding, it can be concluded that metadiscourse teaching in a writing course can help learners improve.

Discussion

This study was carried out with the aim of finding out whether teaching metadiscourse resources in a writing course can lead to any improvement of writing skills of English learners who are studying at the intermediate level. The research allowed over three dozen EFL learners to attend a formal writing course which lasted for nearly two months. During the study, the control group received training in academic writing. The experimental group, in addition to the basics of academic writing, was taught how to use metadiscourse resources in their texts. It should be noted that the number of sessions and the duration of each session were the same for both groups.

At the end of the experiment, it was found that both groups showed improvements in their writing skills as a result of the treatment. After calculating the independent-samples t-test and the effect size, however, it became clear that the experimental group managed to perform significantly better than the control group, leading the researcher to conclude that teaching metadiscourse to learners can in fact help them get better scores in a writing test. Furthermore, in order to measure the magnitude of the findings of the study and to allow comparison with other works in this area, the researcher calculated the effect size using Cohen’s d formula. Accordingly, it was concluded that an average person in the experimental group managed to gain a score which was 0.75 standard deviations above an average person’s score in the control group.

Regarding previous studies conducted on metadiscourse, it is interesting to note that this concept has been mostly studied in theory, with a large number of researchers studying its application in already produced passages such as research papers, theses, and dissertations. The corpus studies carried out in this area have incorporated various genres and topics, including journalistic, narrative or academic genres. However, few researchers have conducted experimental studies on metadiscourse. As mentioned earlier in the study, several studies have been carried out experimentally in this area. These studies have dealt with certain aspects of metadiscourse and their effects on productive skills of English students. However, as mentioned earlier, most of such studies have not reported their effect size or have carried out their research through a pre-test/post-test design, leaving out a control group which could have been used to strengthen their findings. The current study, however, included two randomly-selected groups: the experimental group which received the treatment, and the control group which was used to provide “a baseline for comparison” (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 116). According to Dörnyei (2007), including a control group in a study allows the researcher to “isolate the specific effect of the target variable in an unequivocal manner, which is why many scholars consider experimental design the optimal model for rigorous research” (pp. 116-117). In addition, he stresses that “the ultimate challenge is to find a way of making the control group as similar to the treatment group as possible” (p. 116). Accordingly, prior to the treatment, the author made sure that there was no statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups of the study in the PET test.

The current study integrates the teaching of metadiscourse resources into the syllabus of a writing class. The result of the experiment shows that such a syllabus can be helpful for EFL learners. Thus, teachers who are in charge of writing courses or scholars who are studying ways to make a writing class more fruitful can take into account the importance of metadiscourse in their syllabuses. It is recommended that they make learners acquainted with this concept. One advantage of the current research is that it is a cost-effective approach and can be employed in schools, colleges, or other institutions without a need for a huge financial budget. Teachers and researchers can be familiarized with metadiscourse in a few workshop sessions or an intensive course.

The findings of this study can be improved by repeating the research using a larger number of participants with different levels of competence or learners who have a different ethnic background. The study can also be carried out in a different setting, such as in a college course, a TOEFL or IELTS preparation course, or in an ESL class. It can also be focused on variables such as age, gender, major of study, or profession of the participants.

Conclusion

As was shown in the paper, after nearly two months of training, the treatment group outperformed the control group in the post-test, which means that incorporating metadiscourse resources in the syllabus benefits learners in a way that they are able to produce more successful texts. The study had begun with a homogeneous sample and, hence, the credit for the significant improvement of the treatment group goes to the metadiscourse resources. More research in varying contexts and, perhaps, with different variables such as age-/gender-differences is required to further validate and expand the findings of the present study. Yet, it may not be irrational, at this stage, to conclude that providing learners with the opportunity to practice and implement metadiscourse resources in their language learning process can help them produce more professional discourses. This result should also catch the attention of material developers and teachers. Material developers who take the role of input-providers for English courses should take into account the importance of these resources and need to take the responsibility of including them in their textbooks in order to familiarize learners with such useful concepts. In addition, teachers, in order to help learners improve their writing skills, should provide their classes with opportunities to practice and master these devices.

It goes without saying that improving the writing skills of EFL learners can help them perform better on the writing sections of standardized tests such as IELTS or TOEFL, or probably even on their application letters when applying for a job vacancy. In addition, a piece of text with enhanced cohesion can interact better with readers, and, in fact, increases the chances of comprehensibility of the text.

The present study was conducted in an English Institution. However, owing to the importance of writing skills, especially for the academia, it is highly recommended that similar studies be done in college contexts or probably even high schools. Another variable that can affect the findings is the “level of proficiency” of the learners – i.e., would the result be different for different levels, such as elementary, pre-intermediate, upper-intermediate or advanced learners?

References

Abdi, R. (2009). An Investigation of metadiscourse strategies employment in Persian and English research articles: A study of the generic norms of academic discourse community in Persian research articles. Journal of Language and Linguistics, 9, 93-110. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/215708789[Note: in Farsi]

Abdollahzadeh, E. (2007). Writer’s presence in Persian and English newspaper editorial. Paper presented at the International Conference on Systemic Functional Linguistics, Odense, Denmark.

Ahour, T. & Entezari Maleki, S. (2014). The effect of metadiscourse instruction on Iranian EFL learners’ speaking ability. English Language Teaching. 7(10), 69-75. doi: org/10.5539/eltv7n10p69

Bachman L. F. (1990). Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284-290. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

Coe, R. (2002). “It’s the effect size, stupid: What effect size is and why it is important,” Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, University of Exeter, England. Retrieved from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002182.htm

Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Crismore, A., & Abdollahzadeh, E. (2010). A review of recent metadiscourse studies: The Iranian context.Nordic Journal of English Studies, 9(2), 195-219.

Crismore, A., Markkanen, R. & Steffensen, M.S. (1993). Metadiscourse in persuasive writing: A study of texts written by American and Finnish university students. Written Communication, 10(1), 39-71.

Crocker, L. & Algina, J. (1986). Introduction to classical and modern test theory. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika,16(3), 297-334.

Cullen, P., French, A. & Jakeman, V. (2014). The official Cambridge guide to IELTS for academic and general training. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ebel, R. L. (1979). Essentials of educational measurement. (3rd Edition). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ellis, N. (2000). Editor’s statement. Language Learning. (50)3, xi-xii. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00135.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., Velasco-Sacristán, M., Arribas-Bano, A. & Samiengo-Fernández, E. (2001). Persuasion and advertising English: Metadiscourses in slogans and headlines. Journal of Pragmatics, 33, 1291-1307.

Hyland, K. (1998). Persuasion and context: The pragmatics of academic metadiscourse. Journal of pragmatics,30(4), 437-455. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00009-5

Hyland, K. (2000). Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. London, UK: Longman.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(2), 133-151. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2004.02.001

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing. New York, NY: Continuum.

Hyland, K. (2007). Applying a gloss: Exemplifying and reformulating in academic discourse. Applied linguistics, 28(2), 266-285. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm011

Hyland, K. (2010). Metadiscourse: Mapping interactions in academic writing. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 9(2), 125-143.

Hyland, K. & Tse, P. (2004). Metadiscourse in academic writing: A reappraisal. Applied Linguistics, 25(2), 156-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.2.156

Ismail, H. L. (2012). Discourse markers in political speeches: Forms and functions. Journal of College of Education for Women. 23(4), 1260-1278.

Jensen, A. (2009). Discourse strategies in professional e-mail negotiation: A case study. English for Specific Purposes. 28(1), 4–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2008.10.002

Kopple, W. P. V. (1985). Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. College Composition and Communication, 36, 82-93.

Kopple, W. P. V. (2002). Metadiscourse, discourse, and issues in composition and rhetoric. In E. Barton, and G. Stygall, (Eds.): Discourse studies in composition (pp. 91-113). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Kuhi, D. & Mojood, M. (2014). Metadiscourse in newspaper genre: A cross-linguistic study of English and Persian editorials. Procedia (Social and Behavioral Sciences), 98, 1046-1055. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.515

Le, E. (2004). Active participation within written argumentation: Metadiscourse and editorialist’s authority. Journal of Pragmatics. 36(4), 687-714. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(03)00032-8

Mackey, A. & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mauranen, A. (1993a). Contrastive ESP rhetoric: Metatext in Finnish English economics texts. English for Specific Purposes,12(1), 3-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(93)90024-I

Mauranen, A. (1993b). Cultural differences in academic rhetoric: A textlinguistic study. Frankfort, DE: Peter Lang.

Moghadam, F. D. (2017). Persuasion in journalism: A study of metadiscourse in texts by native speakers of English and Iranian EFL writers. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 7(6), 483-495.

Moore, D. S., & McCabe, G. P. (1993). Introduction to the practice of statistics. New York, NY: Freeman.

Phillips, D. (2007). Longman preparation course for the TOEFL Test: iBT (2nd Edition). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Plonsky, L. & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, (64)4, 878–912. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079

Rahman, M. (2004). Aiding the reader: The use of metalinguistic devices in scientific discourse. Nottingham Linguistic Circular, 18, 29-48.

Siami, T., & Abdi, R. (2012). Metadiscursive strategies in Persian research articles: Implications for teaching writing English articles. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 9, 165-176. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079

Steffensen, M. S. & Cheng, X. (1996). Metadiscourse: A technique for improving student writing. Research in the Teaching of English, 30(2), 149-181.

Stemler, S. E. (2004). A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to estimating interrater reliability. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 9(4), 1-19.

Taghizadeh, M. & Tajabadi, F. (2013). Metadiscourse in essay writing: An EFL case. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 4(7), 1658-1662.

Tan, H., Heng, C. S. & Abdullah, A. N. (2012). A proposed metadiscourse framework for lay ESL writers. World Applied Sciences Journal, 20(1), 1-6.

Tavakoli, M., Varnosfadrani, A. D. & Khorvash, Z. (2010). The effect of metadiscourse awareness on L2 reading comprehension: a case of Iranian EFL learners. English Language Teaching,3(1), 92-102. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v3n1p92

Tavakoli, M., Bahrami, L. & Amirian, Z. (2012). Improvement of metadiscourse use among Iranian EFL learners through a process-based writing course. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 4(9), 129-164.

Vahid Dastjerdi, H., & Shirzad, M. (2010). The impact of explicit instruction of metadiscourse markers on EFL learners' writing performance. The Journal of Teaching Language Skills, 29(2), 155-174. doi: 10.22099/jtls.2012.412

Wei, J., Li, Y., Zhou, T. & Gong, Z. (2016). Studies on metadiscourse since the 3rd millennium. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(9), 194-204.

Williams, J. M. (1981). Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.