Introduction

In the past decades much research has focused on how teacher’s instructional practices can promote Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) (Ladson-Billings, 2009). CRP is a student-centered approach of teaching which recognizes the strengths of students’ cultural experiences to sustain student’s well-being in all aspects of learning (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Previous research suggests that to implement a CRP, teachers must pay attention to the larger institutional and societal contexts (Bailey et al., 2001) by supporting the learners in fostering a cultural-linguistic pedagogical practice. Experts concur that incorporating CRP into the curriculum can address the social and academic needs of the diverse populations, including African-American students. (Kelly-Jackson, Jackson, 2011; Ladson-Billings, 2009). The role of teacher discourse in promoting CRP was also discussed in previous studies. For example, Villegas & Lucas (2002) discussed how a teacher must develop a deep understanding of the diverse cultural background of students and their needs to become culturally responsive to the students. Bailey et al. (2001) claimed that teachers’ training is important to achieve the goals of CRP. Thus, CRP research has been recognized as a pedagogical approach to teach the diverse learners (Gay, 2010).

However, it remains unclear why the role of the teacher’s discourse is not discussed in the previous studies of CRP. Researchers in CRP have reported how theories of CRP can be practiced in classroom, yet limited study offered any theoretical framework to show how teacher discourse can create an opportunity to foster CRP when teaching diverse learners.

Therefore, the present study aims to highlight the idea of introducing a successful teacher discourse framework for sustaining this CRP in a diverse classroom context at one of the Midwest US universities. The paper has three purposes: to examine the impact of teacher’s discourse on diverse learners to promote CRP, to observe the effectiveness of teacher’s discourse to reduce cultural gaps which is one of the goals of CRP, and to advocate for following a teacher-discourse framework to achieve the goals of CRP in a diverse classroom.

Literature Review

A handful of studies in CRP have addressed the need for cultural practices in sustaining a CRP in different contexts. Researchers in CRP have reported how theories of CRP can be practiced in classroom, yet no study used the theoretical framework for offering teacher discourse the opportunity to foster this approach when teaching diverse learners.

Most research on CRP has focused on how teacher’s instructional practices can promote CRP environments (Ladson-Billings, 2009). Many researchers have agreed that CRP is an effective strategy for integrating students’ cultures into the curriculum and addressing the social and academic needs of African American students and other diverse populations (Kelly-Jackson & Jackson, 2011; Ladson-Billings, 2009).

Co-construction of meaning in CRP to reduce cultural gap and to develop content knowledge

In recent years, a number of researchers discussed the need to raise awareness about the value of multilingualism and the relationships between language, identity, and culture (Lucas & Villegas, 2013) to implement a CRP in a diverse classroom context. In their study, they showed how individual cultural identities impact language learning and student achievement in the school context. The authors discussed four types of pedagogical skills a CRP teacher should adopt:

- knowledge of the learners’ cultural background,

- knowledge of key linguistic features to address CRP when teaching diverse learners,

- to identify learners’ language demands, and

- to scaffold classroom instructions in the light of CRP.

That means their study emphasized the importance of incorporating CRP into classroom instruction. Research mentioned teacher preparation to implement CRP, but they did not offer any framework for how a valid discourse to implement these skills to address the diverse learners’ needs can be followed. Researchers also discussed developing content knowledge for implementing CRP, but they did not propose any framework on how to integrate content knowledge in practice. Classroom discourse is defined as the dynamic interactional process of constructing meaning between teacher and student emerging from the utterances sequentially with one another (Nystrand, 2006).

Teachers’ instructional practices and CRP

Several studies suggest that a teacher’s effective instructional practices promote a CRP (Gay, 2010; Ladson-Billings, 2009) for diverse learners. To promote this practice of culturally responsive pedagogy, teachers often demonstrate an ethic of caring ‘‘to the needs, motivations, and perspectives” of their students (Hersi & Watkinson, 2012, p. 100) regardless of their color or background. This care supports the educational achievements of approaches to implement CRP in the language classroom focusing more on academic success. Some studies have suggested that CRP views cultural variation as a challenge. In order to address it a teacher should know the cultural differences of students by accepting their cultural styles (Gutierrez & Barbara, 2016). To know their cultural styles and differences, a teacher must help the learners in a way so that they do not perceive themselves as inferior because of their minority language or culture (Cummins, 1993).

Classroom discourse to engage learners’ active participation

According to Walshaw and Anthony (2008), there are differences between two major teaching strategies in a productive classroom discourse. These differences are necessary to validate discourse participation rights and responsibilities between the teacher and students with a purpose of engaging students in the classroom conversation. In this way the students are guided by giving individual productive feedback to facilitate their further thinking process.

Theoretical bases of this study

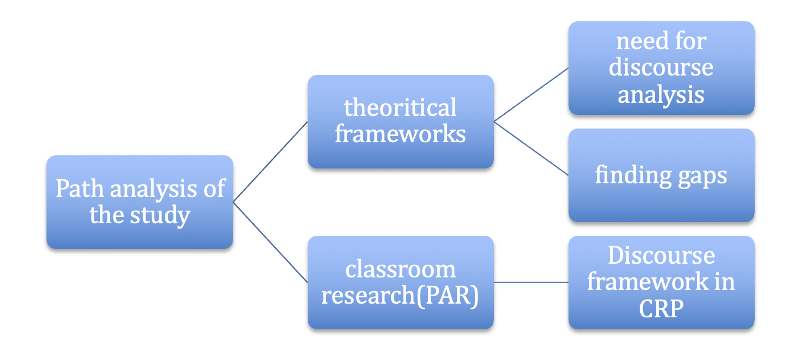

Based on the theoretical framework, this paper focuses on how a teacher’s discourse can connect the students’ needs addressing the CRP practices. In this review of literature, the researcher has attempted to articulate how this study is situated at the position of two frameworks: one largely theoretical (CRP theories of other researchers) and one contextual (the use of teacher’s discourse in a specific English classroom). The gaps between the theories of CRP shaped the conceptualization of the study, and how the data collected was analyzed. It was found in a study that one of the major challenges for CRP practitioners is that the teachers are not prepared to address the needs of diverse students in their classroom (Cummins, 2007). Moreover, Villegas and Lucas (2002) suggested that the teacher educators need to employ a critical examination of teachers’ coursework, learning experiences, and research fieldworks which may help them to work with the diverse students in an efficient way . Inspired by these researchers, the study examined how a structured classroom discourse can contribute the CRP practices of future educators by cultivating cross-cultural communication. To promote this, teachers can treat cultural differences as individual traits of the learners (Banks & Banks, 1995; Gay, 2000; Nieto, 1999) and shift their experiences to participate into cultural practices for those learners (Moll, 2000) by implementing a successful classroom discourse. Inspired by this previous research , this study offers an exploration of the impact of teacher’s discourse on diverse learners and thus analyzes how the teacher’s discourse sustains the goals of CRP.

Centered on CRP theories, this paper advocates the idea of including classroom discourse to reduce the gaps of classroom practices and to offer a sustainable framework for attaining positive beliefs regarding CRP. This will not only create an inclusive classroom for diverse learners without any restrictions based on race, color or identity. This paper seeks to understand how such discourse works in a diverse learners’ environment, and what components of teacher’s talk are likely to serve as addressing to connect these diverse learners with CRP.

Figure 1: Path analysis of the study

Methodology

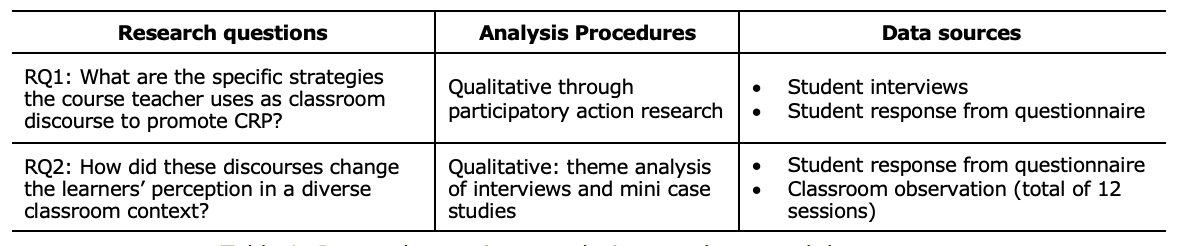

In this study, the researcher investigates the effect of teacher’s discourse on diverse learning context in fostering CRP through Participatory Action Research (PAR). The research questions are:

RQ1: What are the specific strategies the course teacher uses as classroom discourse to promote CRP?

This question is formulated to directly analyze the learners’ response in exploring the discourse strategies, used in the class, that promote CRP in a broader context.

RQ2: How did this discourse change the learners’ perception of cultural equality?

This question is intended to explore how these discourses impacted the learners when it comes to cultural equality. It is designed to analyze the effects of classroom discourse on diverse learners.

Table 1: Research questions, analysis procedures, and data sources

Research methodology

Participatory Action Research Approach

The research study utilizes a Participatory Action Research method to involve the participants in collecting the empirical data. The study's sample comprises 11 participants who attended a research course at a Midwest university in the United States during the Fall Semester of 2021.

The participants and instrumentation

The students participating belonged to diverse communities living in the United States as second generation. They were mostly Asian, European, Egyptian, and Mexican. They were aged between 23 to 33. They were multilingual; therefore, they had a diverse linguistic background. The researcher chose them purposively to examine the impact of the teacher’s classroom discourse on students from a diverse cultural and linguistic background. That means the study aims at finding the impact of teacher’s discourse on students who come from different cultural backgrounds or if that has any impact. To examine the role of the teacher’s classroom discourse on the diverse students., the researcher implemented stimulus sets of sample instant messaging and email correspondence between the instructors who answered the survey questions in an informal way.

The study survey questions were designed to reveal the effect of teacher’s discourse on their perception. The specific discourse pattern of the course teachers was analyzed to assess a CRP practice on the diverse learners. First, the participants entered their perceptions of characteristics such as the teacher’s use of race talk, gender talk, and identity talk in the classroom. Second, the subjects were offered open-ended text boxes to fill in information about any further perceptions of the classroom discourse. In addition, two mini case studies were also conducted for deeper understanding of the theme. At the end, learners gave some recommendations for the proposed framework. The duration of the entire experiment was 10-15 minutes per learner.

Consent from the participants

The participants were clearly informed about the research design and its purpose. They signed a written consent form indicating their consent to participate in the study in its entirety. Later, the researcher sent an email to learners to ensure their consent. The email indicated the aim of the study. This study engaged the research participants in three phases: (i) participation, (ii) action, and (iii) analysis of the research findings. Primary data collected from the field was used to assess the needs for this study and to eventually address existing problems.

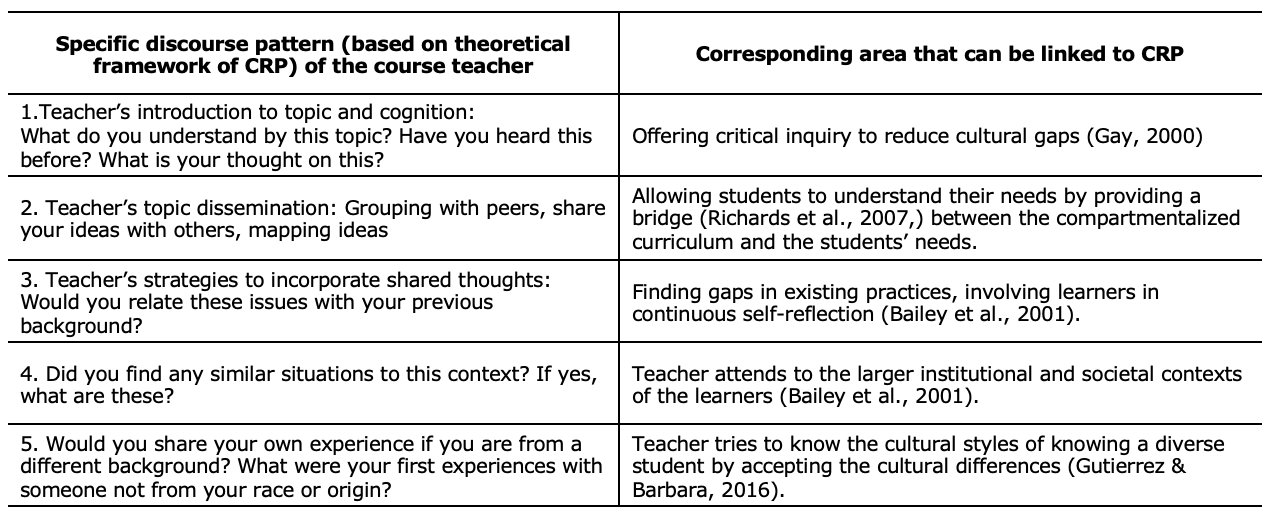

To conduct the research, the following discourse that the course teacher used for CRP implementation in the graduate classroom was examined. It was found out that the discourse included previous theoretical frameworks of CRP. The following table shows how the specific classroom discourses of the course teachers addressed the theoretical bases of CRP and how they connected the links for the diverse learners to sustain CRP practices in graduate classrooms.

Table 2: Classroom discourse observed while the course teacher used to address CRP for the diverse students

In the above table, the researcher mentioned the classroom discourses that the course teachers used while instruction in the class of the course being observed. The first question observes how the course teacher introduces the topic to the students in every class. The second question seeks to assess whether the teacher helps the students during the discussion to clarify the topic. Additionally, the third question exposes how the teacher relates the diverse learners’ background knowledge to the course contents. Similarly, the fourth question reveals the learners’ experiences to use CRP in different cultural orientations. These questions were monitored while the researcher observed the classes for the entire semester from September to December 2021.

Data Analysis and Findings of the study

To anticipate the results of the proposed study, data were collected from 11 participants of one class (the sample size, n= 11 and the total population/number of students of the sample, n= 16).

Data analysis

The researcher conducted data analysis in three phases:

(i) An examination of qualitative survey data for identifying the impact of teacher’s discourse in the course;

(ii) An integrated consideration of data sources from the students’ interviews and students’ perceptions of the study through a questionnaire (Appendix 1) and the mini case studies (Appendix 2);

(iii) An observation of teacher’s classroom discourses (Appendix 3)

Preliminary data were collected from the three participants in order to address the research questions of the study. The rest of the participants were included later. The researcher sent a set of questionnaires to each participant, who then emailed the researcher their answers. The researcher took notes on the themes discussed during the classes when the instructor addressed CRP discourses spontaneously and kept the participants responses private and separate from each other. In the first stage of the data analysis, the researcher focused on the responses of the participants who gave full explanations of the questions. Most participants responded positively to the study. They also indicated that they felt their course instructor was following the goals of CRP in their classroom. They recommended having a culturally responsive classroom to establish equality.

Teacher’s introduction to topic

The first interview question addressed how the course instructor introduced the topics in the class, and all participants answered that the instructor engaged them in critical inquiry to understand the values of cultural differences. They added that it helped reduce cultural gaps.

Teacher’s strategic discourses to disseminate topics of this course

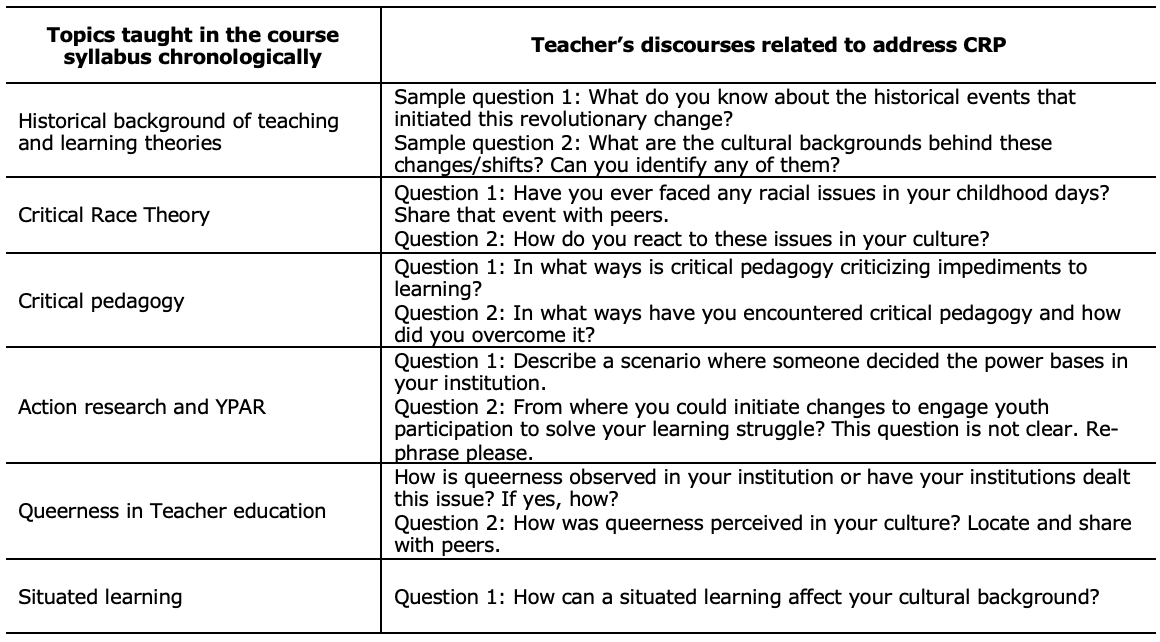

The second research question was focused on teacher’s discourses used in this course to teach different topics to the students. The participants reported that the teacher organized peer group discussions that helped them feel they belong to the same cultural groups. The following discourses were recorded to explore the relation between the teacher’s discourse and CRP practices during the close observation:

Table 3: Intended course discourses on course contents addressing the goals of CRP

The course instructor asked the students to provide answers to these questions in groups and gave them time to reflect on their answers before sharing their thoughts with others. This helped the learners in two ways: First, they could relate their cultural knowledge with these topics when they were asked, and second, they could get insights on cultural ideas on these contexts. Thus, the discourses framed by the instructor of intended course were found to address the goals of CRP in a graduate classroom.

Teacher’s strategies to incorporate shared thoughts

CRP closely involves learners in continuous self-reflection (Bailey et al., 2001), and the course instructor continuously provided opportunities for the students to share their previous experiences with others and ‘pushed’ them to find gaps in existing practices. The students reported that they felt that they belong to the same umbrella of cultural repertoires when the teacher addressed issues this way. This is very significant to foster CRP in a diverse context.

Attitude of the instructor to engage the students in larger contexts

In a mini case study, the data were collected to shed light on how the students feel about the instructor’s delivery of messages for larger contexts. One participant reported:

I strongly feel connected in the classroom though I am from a different cultural background. You know when the teacher asked if I know any struggles in understanding queerness, his attitude helped me a lot to understand the cultural ethos of queer people, in fact, he opened an eye how to deal with the idea of queerness in larger contexts. At some points, I felt that the teacher could relate the issues of critical race theories that really inspired me to know more about this for further study. I am truly impressed by the discourses he used in this course that motivated me to understand other cultural background. (Nick)[1]

The results inspired my study to continue for further examination of the validity of the research questions to suggest for establishing a CRP for the culturally diverse learners at a US university.

Discussion

Based on the primary analysis of the data, the study anticipates the following findings in two parts: First, the study can be conducted in larger contexts to assess how CRP could be implemented in a diverse context through teacher discourse. Second, the study could inspire future educators of CRP to conduct research in diverse contexts to find the gaps in existing theoretical frameworks of CRP.

Developing cross-cultural understanding in graduate students

The study explored how an instructor fostered a sense of cross-cultural understanding in graduate students about CRP by maintaining a discourse pattern through the semester. The participants reported that they expected other courses to foster this kind of perception. This was evident from the following conversation recorded with another participant of this study:

Case study 1: Ricky

The researcher interviewed Ricky on how he felt about the course and if it met the requirements of a CRP practice:

Truly speaking, this course was an amazing one! I never felt that I have [sic] any cultural barriers when I attended this course, I could relate the gaps in existing situations clearly. It motivated me to know more about other issues that happen in other cultures. Yes, of course I agree, if we want to foster a CRP, this instructor helped me to shape my thoughts [sic].

The study method was based on PAR to rationalize the feasibility of the proposed study. The study can be demonstrated in a larger context to find the effectiveness of teacher’s discourse for sustaining a CRP.

Case study 2: Daniel

Daniel was asked: Do you feel that this course can foster CRP in larger contexts?

If I examine the goals of CRP, I clearly see the discourses used by the instructor can foster a CRP classroom for all. Indeed, it can be a role model for others to adopt such discourses if they want to address CRP practices in their language classroom. As a language practitioner, I strongly believe that if the instructor can address something like engaging every student inclusively, then the learning will also be smooth you know, and it is very effective for learning a language too in a diverse context.

Conclusion

This study can offer an effective framework for future educators who need to develop a CRP classroom that corresponds to race theory perspective. Further research can also be conducted on the teachers’ linguistic strategies used for managing race talk through the practices of CRP, or the challenges a teacher faces while conducting this sort of discourse. Answering these questions can lead us to resolve the challenges of practicing a CRP in a diverse classroom where multiple theoretical perspectives may include Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Critical Discourse Theory (CDA). To sum up, this kind of study can validate the use of powerful classroom discourse to recognize a culturally instructional pattern for establishing CRP. The study will lead us to one shared goal of sustaining educational equity among diverse learners.

References

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., & Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: The self as source. Heinle & Heinle.

Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (1995). Handbook of research on multicultural education. Macmillan.

Cummins, J. (1993). Empowering minority students: A framework for intervention. In L. Weis & M. Fine (Eds.), Beyond silenced voices.State University of New York Press.

Cummins, J. (2007). Pedagogies for the poor? Realigning reading instruction for low-income students with scientifically based reading research. Educational Researcher, 36(9), 564-572. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X07313156

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2010). Acting on beliefs in teacher education for cultural diversity. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 143–152.https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347320

Hersi, A. A., & Watkinson, J. S. (2012). Supporting immigrant students in a newcomer high school: A case study. Bilingual Research Journal, 35(1), 98-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2012.668869

Kelly-Jackson, C. P., & Jackson, T. O. (2011). Meeting their fullest potential: The beliefs and teaching of a culturally relevant science teacher. Creative Education, 2(4), 408-413. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2011.24059

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory into Practice, 52(2), 98-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.770327

Moll, L. C. (2000). Inspired by Vygotsky: Ethnographic experiments in education. In C. Lee & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Vygotskian perspectives on literacy research: Constructing meaning through collaborative inquiry (pp. 256-368). Cambridge University Press.

Nieto, S. (1996). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. Longman.

Nystrand, M. (2006). Research on the role of classroom discourse as it affects reading comprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, 40(4), 392-412. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40171709

Richards, H. V., Brown, A. F., & Forde, T. B. (2007). Addressing diversity in schools: Culturally responsive pedagogy. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(3), 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990703900310

Walshaw, M., & Anthony, G. (2008). The teacher's role in classroom discourse: A review of recent research into mathematics classrooms.Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 516-551. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543083202

[1] Pseudonyms were used to conceal participants’ identities.