Background

Most recent SLA research shows that input, output, and interaction are all important to successful instructed language learning. The significance for teachers and course planners is that they should give appropriate consideration to all three features (Ellis, 2005; Lessard-Clouston, 2007).

As for input, Gass (1997) points out that “it is an incontrovertible fact that some sort of input is essential for language learning; clearly languages are not and cannot be learned in a vacuum” (p. 86). Maley (2009) stresses that the only reliable way to learn a language is through repeated exposure to large amounts of input in context.

With regards to output, Swain (1995) asserts that output in meaningful situations plays a vital role in language development. She explains that, as well as providing learners with opportunities for practice and helping them to improve their fluency, output serves the second language learning process in three important ways. It gives learners chances to: “notice (any gaps) between what they want to say and what they can say”; develop and test hypotheses about how the language works; and “reflect upon their own target language use” and “internalize (their) linguistic knowledge” (pp. 125-126).

Having the opportunity to interact in the second language, says Ellis (2005), is also of central importance to developing L2 proficiency. He points out that both input and output occur in oral interaction, and he stresses that “interaction is not just a means of automatizing existing linguistic resources but also of creating new resources” (Ellis, 2005, p. 40). Language acquisition is promoted when the speakers have to negotiate for meaning and “interactional modifications” (Ellis, 2005, p. 40) are made. In fact, studies have found that modified interaction leads to higher levels of comprehension than modified input (Lightbown & Spada, 1999).

Although most SLA researchers now agree that L2 learners need exposure to input as well as opportunities for output and interaction in meaningful situations in order to make progress, there is a tendency with some of the more influential approaches to language teaching to focus on only one or two of these features. Proponents of Communicative Language Teaching and the Task-based Approach, for example, emphasize learning by doing and argue that learners learn a language by using it in meaningful communication (Richards, 2006). Typical courses based on these methodologies come down heavily on language output, interaction, and accomplishment of tasks (Swann, 2006).

On the other hand, the Natural Approach, as advocated by Krashen and Terrell, stresses the importance of input rather than output in language learning. Supporters of this approach claim that output should not be forced and students will produce language spontaneously after they have been exposed to large amounts of comprehensible input (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). Krashen, in Wang (2013) says that speaking and writing are not essential for learning to take place and learners will be able to learn a language without these components as long as there is sufficient comprehensible input; “More writing,” he claims, “does not result in better writing,” and “More speaking does not result in better speaking”. (Wang, 2013, p. 26) However, he does concede that conversations can be helpful for the language learning process in that they provide input (Wang, 2013, p. 26).

While acknowledging the contribution and importance of the above-mentioned approaches to language teaching, some EFL scholars point out their limitations. Renandya (2013) suggests that courses that neglect input and emphasize output and interactive activities can lead to fossilization of errors and without a rich and varied input, students will reach a plateau of ability and cease to develop language competence. He argues thatlanguage programs must not neglect input activities and should provide an appropriate balance of input and output practice activities for L2 learners to engage in on a sustained basis. Swain, on the other hand, as mentioned in Kreß (2008), argues that it is important not to neglect output, as it is necessary to the language learning process. She points to empirical studies that were carried out in Canada and Japan, which show that language learning students who were not 'pushed' to perform output activities were unable to develop their speaking and writing abilities to the same extent as their reading and listening skills (Kreß, 2008). Other EFL experts stress the importance of interaction as well (Ellis, 2005; Lightbown & Spada, 1999; Mackey & Gass, 2005). Ellis (2005) explains that courses that neglect to provide opportunities for interaction deprive students of a “primary source of learning” (p. 40).

One of the challenges facing language course planners, therefore, is to provide students with a well-balanced language program that recognizes the importance of language input as well as output and interaction practice. Ellis (2005) insists that any successful instructed language-learning program should include extensive L2 input, opportunities for output, and the opportunity to interact in the L2. Similarly, Nation (1996) and Swann (2006) stress that attention should be paid to both input and output when planning language programs. Nation (1996) recommends that teachers and course designers should avoid allying themselves too strongly with any one teaching approach and should instead aim to create a language program which includes “four strands”: meaning-focused listening and reading, language-focused instruction, meaning-focused speaking and writing, and fluency-development activities. Swann (2006) claims there are certain elements that are essential for any language-learning program: extensive input, intensive input, analyzed input, extensive output, intensive output, and analyzed output.

An Integrated Approach and the Research Questions

Although carried out in two different ways, the approach used in the classes attended by the students in this study sought to engage the students in a combination of classroom activities that together provided abundant and wide-ranging input as well as opportunities for output and interaction, and which involved all four language skills. As it occurs in real life usage, the practice of these skills was linked to or focused on the same content, thus allowing for the recycling of language. This was intended to provide repeated exposure to the input, increased opportunities for reinforcement, a greater understanding of the meaning and usage of the language, and an increased awareness of how the language is used in communication.

The initial activity involved the students reading either at home or in class. The reading material varied, and was chosen in one case by the students and the other by the teacher. In both cases, the hope was that the material was interesting to talk about and comprehensible. Incountries where the target language is not widely used, reading can be one of the most comprehensible forms of input. Moreover, if learners develop the habit of reading extensively in their free time, they will brought into contact with far more input than classroom lessons can ever provide (Maley, 2009).

Another activity required the students to write down information and/or opinions and ideas related to the material they had read. Having the students write about a text can help them to gain a deeper understanding of it by encouraging them to move beyond focusing on individual elements and towards an understanding of overall themes. It also gives them chances to practice using vocabulary and expressions found in the text. In addition, writing can help students to prepare for a spoken discussion, giving them opportunities to clarify and organize the details as well as to reflect on their opinions and thoughts regarding the content. Writing down one’s thoughts before speaking, can make a big difference in both the quality and quantity of the spoken language produced (Folse, 1996).

In other activities, the students talked about and discussed the material they had read with a partner or in groups. This was done without looking at what they had written in order to avoid simply reading aloud and to encourage real conversation. As well as providing speaking and listening practice, the discussions, provided opportunities for the students to actually use the vocabulary and expressions from the text. It also forced them to negotiate for meaning when they had trouble understanding or being understood.

Our basic research question concerned whether or not the students were able to perceive the benefits of this approach for the performance and development of their English language skills. Specifically, the questions investigated were as follows:

1. Did the students think that their understanding of the reading passages was helped by taking part in activities that involved other skills and were based on the same content area?

2. Did the students think that their performance in the discussions was helped by taking part in activities that involved other skills and were based on the same content area?

3. Did the students think that a combination of various skill-based activities helped them more in developing their receptive abilities than practice in only a single skill?

4. Did the students think that a combination of various skill-based activities helped them the more in developing their productive abilities than practice in only a single skill?

Methodology

The participants for this study were a convenience sample rather than a random sample of students enrolled in three university English classes in Japan. The anonymous ten-item questionnaire (Appendix A) was administered to those in attendance on that day; 19 of the 20 students enrolled in class A and 47 of the 50 students enrolled in classes B and C. The total number of participants was 66 students. Most students spent about ten minutes answering the questions. (Appendix B provides information about the students’ basic level of English proficiency.)

Class A was taught at one university by a native English speaker, and classes B and C were taught at another university by another native English speaker. Class A was a mandatory one-semester reading class for second-year English language majors. It met twice a week for 90 minutes each, on Mondays and Thursdays. This was the seventeenth lesson of the semester, during the ninth week of the second semester. In the first 15-week semester, the students had taken a similar class, but were not all in the same section and were not taught by this teacher nor all by the same teacher. Besides this class, these students were taking three other required English classes during the semester and the school year; writing, speaking, and listening, each also meeting for 90 minutes twice a week.

Classes B and C were compulsory integrated-skills classes for these first-year students, who were not majoring in English. It was conducted for the entire school year, for two 15-week semesters with summer vacation in between. The classes met for 90 minutes once a week, on Wednesdays. This was the tenth lesson of the second semester; so, the twenty-fifth lesson of the school year. Eighty percent of these students had been in the same two sections of this class taught by this same teacher in the first semester. The other twenty percent had been in different sections taught by other teachers. In addition to this class, these students were enrolled in two other 90-minute, once-a-week, required English classes during each semester; one emphasizing listening and speaking and another emphasizing reading but including some writing. Most of these students were also taking at least one of a variety of other elective English classes, carried out according to the same weekly schedule. As classes B and C were taught following the same procedures and using the same materials, they will be considered together. (For details about the class activities, see Appendix C.)

Results and Discussion

In general, the students’ responses to the questionnaire revealed that the majority of the students in both groups found the use of various language skills helpful in their use of and improvement in each individual language skill. The analysis focuses on the four specific research questions. In the tables, which provide details, percentages may not equal to 100 due to rounding. In the following tables these are the rankings that were used: 1 (I agree strongly), 2 (I agree), 3 (Maybe), or 4 (I do not agree).

1. Did the students think that their understanding of the reading passages was helped by taking part in activities that involved other skills and were based on the same content area?

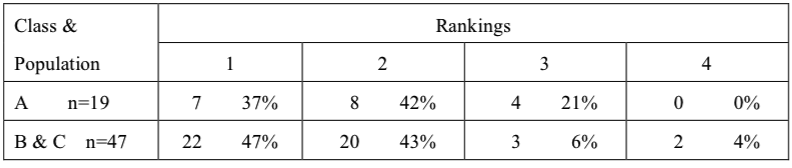

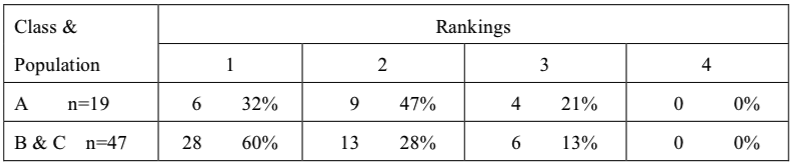

Table 1. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Having conversations helped me to understand what I had read

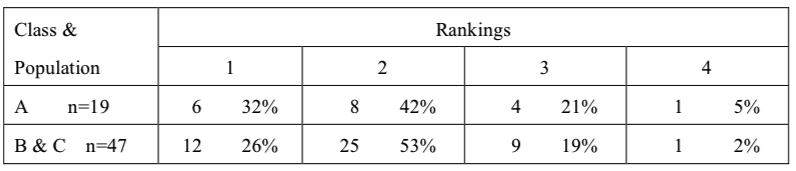

Table 2. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Writing helped me to understand what I had read

In Table 1, we find that 79% of the students in class A (37%+42%) and 90% of the students in classes B and C (47%+43%) felt sure that having conversations helped them to understand what they had read, and only two students in classes B and C (4%) thought that this was definitely not so. Table 2 reveals that 74% of the students in class A (32%+42%) and 79% of the students in classes B and C (26%+53%) were certain that writing helped them to understand what they had read, with one student in each group, 5% and 2%, respectively, disagreeing. These results find the answer to the first question to be yes; the great majority of these students believed that having taken part in language-based activities other than reading, which were based on the same text, helped them to understand what they had read.

2. Did the students think that their performance in the discussions was helped by taking part in activities that involved other skills and were based on the same content area?

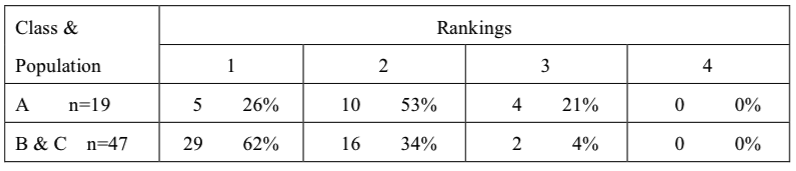

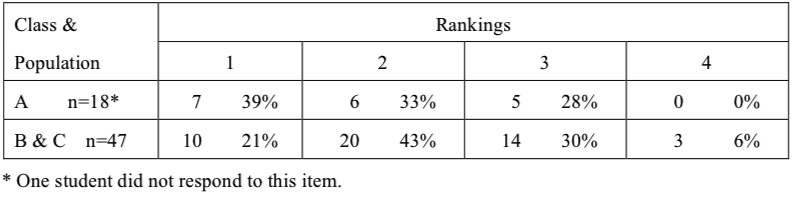

Table 3. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Reading something before talking helped me to say more when I had conversations

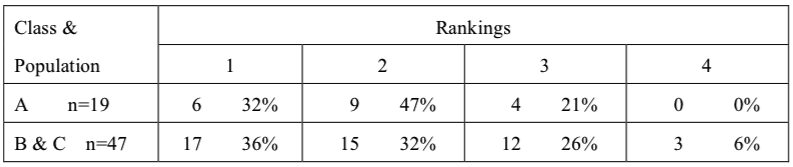

Table 4. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Writing something before talking helped me to say more when I had conversations

Table 5. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Reading something before talking helped me to understand more of what my classmates said in the conversations

Table 6. Numbers of students who ranked the statement: Writing something before talking helped me to understand more of what my classmates said in the conversations

Table 3 shows us that 79% of the students in class A (26%+53%) and 96% of the students in classes B and C (62%+34%) thought that reading something before talking helped them to say more when engaged in conversations, while no students felt that this was definitely not the case. In Table 4, we see that 79% of the students in class A (32%+47%) and 68% of the students in classes B and C (36%+32%) believe that writing something before talking helped them to say more in their conversations, with only three students in classes B and C, 6%, disagreeing. Table 5 shows us that 79% of the students in class A (32%+47%) and 88% of the students in classes B and C (60%+28%) were sure that reading something before talking helped them to understand more of what their classmates said in conversations. Table 6 reveals that 72% of the students in class A (39%+33%) and 64% of the students in classes B and C (21%+43%) felt certain that writing something before talking helped them to understand more of what their classmates said during conversation, while three students in classes B and C (6%) disagreed. According to these results, the answer to the second question is also yes; a majority of these students thought that having taken part in language-based activities other than conversing, and which were related to the same material, helped them to perform better in their discussions. A much higher percentage of students in classes B and C agreed with this for reading (96% and 88%) than for writing (68% and 64%), whereas the percentages were almost the same for class A students (79% and 79% versus 79% and 72%). Perhaps this is because the students in classes B and C were given much more time for their reading than for their writing. The students in class A were provided similar amounts of time to do both.

3. Did the students think that a combination of various skill-based activities helped them more in developing their receptive abilities than practice in only a single skill?

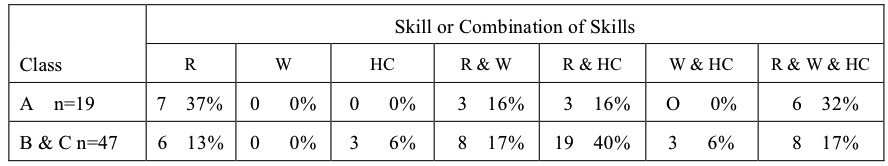

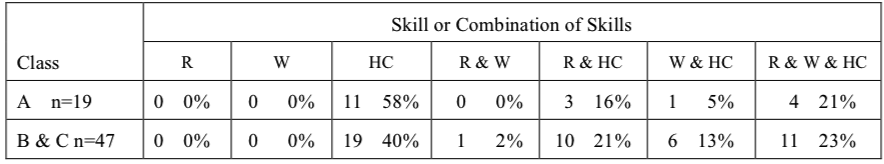

Table 7. Numbers of students who chose each skill, R, W, HC (reading, writing, having conversations), or combination of skills (R & W, R & HC, W & HC, R & W & HC) as the most helpful to them to become better at reading

Table 8. Numbers of students who chose each skill, R, W, HC (reading, writing, having conversations), or combination of skills (R & W, R & HC, W & HC, R & W & HC) as the most helpful to them to become better at listening

Table 7 shows that 64% of the students in class A (16%+16%+32%) and 86% of the students in classes B and C (6%+17%+40%+6%+17%) thought that some combination of skills practice was more helpful for them to become better at reading than practicing reading alone, 37% and 13%, respectively. In Table 8, we find that 32% of the students in class A (5%+11%+16%) and 55% of the students in classes B and C (4%+30%+6%+15%) believed that practicing some combination of skills was more useful for improving their listening abilities than just having conversations, 63% and 43%, respectively. These results show that a majority of the students, a great majority of those in classes B and C (86%), felt that practicing a variety of language skills helped them more to develop their reading abilities than reading alone. The results concerning becoming better at listening are not as clear. As listening was almost always carried out in conversations, this skill was not a separate choice here. But, having conversations was not included when totaling the number of students who felt a combination of skills helped them to improve their listening. Still, a greater percentage of students in classes B and C (55%) thought that practicing a variety of other language skills was more helpful to them in developing their listening abilities than only having conversations (43%). The students in class A felt the opposite; 63% believed that having conversations helped them the most to become better at listening.

4. Did the students think that a combination of various skill-based activities helped them more in developing their productive abilities than practice in only a single skill?

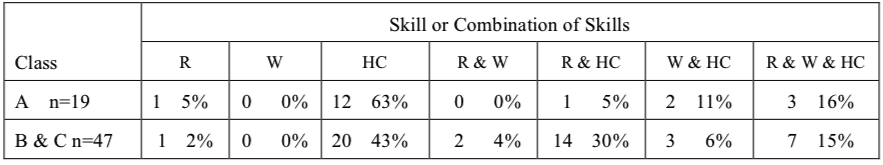

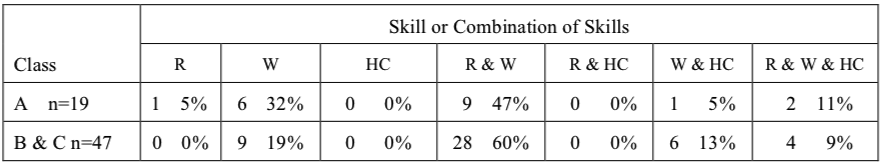

Table 9. Numbers of students who chose each skill, R, W, HC (reading, writing, having conversations), or combination of skills (R & W, R & HC, W & HC, R & W & HC) as the most helpful to them to become better at speaking

Table 10. Numbers of students who chose each skill, R, W, HC (reading, writing, having conversations), or combination of skills ( R & W, R & HC, W & HC, R & W & HC) as the most helpful to them to become better at writing

Table 9 shows us that 42% of the students in class A (16%+5%+21%) and 59% of the students in classes B and C (2%+21%+13%+23%) felt that practicing a combination of skills helped them to become better at speaking than only having conversations, 58% and 40%, respectively. Table 10 reveals that 63% of the students in class A (47%+5%+11%) and 82% of the students in classes B and C (60%+13%+9%) thought that a combination of skills practice was more beneficial for becoming better at writing than only practicing writing, 32% and 19%, respectively. According to these results, a majority of the students, a strong majority of those in classes B and C (82%), felt that practicing a variety of language skills helped them more to develop their writing abilities than writing alone. The results concerning becoming better at speaking, as in the case of listening, are not as clear. As with listening, this may be because speaking was almost always carried out in discussions, which was not listed as a separate choice and was not included as a combination of skills, either. Yet, a greater percentage of students in classes B and C (59%) thought that practicing a variety of other language skills was more helpful to them in developing their speaking abilities than only having conversations (40%). Again, students in class A had the opposite opinion, with 58% feeling that having conversations helped them the most in becoming better at speaking.

Conclusion

In the English language teaching context of Japanese universities, English courses, other than those of English majors, are only a very small part of the curriculum. There are frequently only two English lessons a week, which are two separate courses and are sometimes only required of first-year students. The teacher therefore has a lot of choices to make to ensure efficient and effective use of the short learning time available.

Japanese university English courses are often separated by skills, or by combining the literate skills or the oral/aural skills. As in high school classes, lessons quite often focus on input and translation into Japanese, with very little output or interaction in English being required. So, for many of the students, the approach used in this study, which involved a balance of input, output, and interaction and an integration of all four skills, was new.

Our research questions attempted to ascertain if the students thought they had improved their English reading, writing, speaking, and/or listening through participation in a variety of language learning activities emphasizing each of these skills and based on the same reading passage. To a great extent, the students’ responses to the questionnaire were that they did, which is extremely important as perception of improvement is likely to inspire motivation to continue studying and learning. They overwhelmingly believed that both having conversations and writing helped them to better understand what they had read and that both reading and writing helped them to both speak and understand more in conversations. They also strongly believed that practicing various skills helped them to improve both their reading and their writing more than if they had only practiced the single skills.

The only results that might be at variance with support for this approach concerned what students thought helped them most for the development of their oral/aural skills. As was mention earlier, this may have had to do with the wording of the questions. In any case, the majority of students in classes B and C still felt that practicing other skills along with having conversations was more helpful than only having conversations, but not to the same extent that they believed combining various skills’ practice was useful for improving reading or writing. The majority of the students in class A, however, had the opposite general opinion, believing that conversation alone was more helpful for them to improve their speaking and listening than combining it with the practice of literate skills.

Overall, this study has found very strong support for an integrated approach to teaching English as a foreign language, which includes input, output, and interaction activities, and which requires using all four skills, based on the same materials. It would be useful to carry out further research into the effectiveness of the approach described in this paper using more objective methods of assessment.

References

, Comparing TOEIC and TOEFL Scores. Amideast.org. Retrieved on Sept 29, 2014, from: http://www.amideast.org/sites/default/files/otherfiles/hq/advising%20testing/toeic_toefl_score_comparison.pdf.

Ellis, R. (2005). Instructed Second Language Acquisition. A Literature Review. Report to the Ministry of Education. Auckland: Auckland UniServices Limited.

Folse, K. (1996). Discussion Starters. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Gass, S.M. (1997). Input, Interaction, and the Second Language Learner. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Kreß, C. (2008). The Role of Language in Spoken Discourse. Norderstedt: Druck und Bindung.

Lessard-Clouston, M. (2007). SLA: What it offers ESL/EFL teachers. In G. Anderson & M. Kline (Eds.), Proceedings of the CATESOL State Conference, 2007. Orinda, CA: CATESOL. Retrieved on Sept, 29, 2014 from: http://www.catesol.org/07Lessard-Clouston.pdf.

Lightbown, P. M. & Spada, N. (1999). How Languages are Learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mackey, A. and Gass, S.M. (2005). Second Language Research Methodology and Design. Abingdon: Routledge.

Maley, A. (2009). Extensive reading: Why it is good for out students…and for us. TeachingEnglish.org. London: British Council & BBC World Service. Retrieved on Sept. 29, 2014, from: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/extensive-reading-why-it-good-our-students%E2%80%A6-us.

Nation, P. (1996). The four strands of a language course. TESOL in Context, 6(1), 7-12. Australian Council of TESOL Associations. Retrieved on Sept. 29, 2014, from: https://www.victoria.ac.nz/lals/about/staff/publications/paul-nation/1996-Four-strands.pdf.

Renandya, W.A. (2013). The role of input- and output-based practice in ELT. In A. Ahmed, M. Hanzala, F. Saleem, & G. Cane (Eds.), ELT in a Changing World: Innovative Approaches to New Challenges, (pp. 41-52). Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Richards, J.C., & Rodgers, T.S. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J.C. (2006). Communicative Language Teaching Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swain, M. (1995) Three functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principle and Practice in Applied Linguistics, (pp. 125-144). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swann, M. (2006). Two out of three ain't enough: the essential ingredients of a language course. In IATEFL 2006 Harrogate Conference Selections, (pp. 45-54). International Association of Teachers of English a Foreign Language. Sept. 29, 2014, from: http://www.mikeswan.co.uk/elt-applied-linguistics/Two-out-of-three-aint-enough-the-essential-ingredients-of-a-language-course.

TOEIC-TOEFL Conversion Table. (2009). online learning japan. Retrieved on Sept. 29, 2014, from http://onlinelearningjapan.net/english/toeflvstoeic_eng/.

Wang, M. (2013). Dr. Stephen Krashen answers questions on the comprehension hypothesis extended. The Language Teacher, 37(1), 25-28.