Introduction

Speech delivery affected by stage fright is a common dilemma for all students across different proficiency levels and cultural orientations. These factors, which may impact delivering messages in front of a large crowd, include self-esteem, confidence, frustration, and anxiety (see Valencia & Nader, 2008; Edwards, 1998-2008). According to Oxford (1990), “the affective side of the learner is probably one of the most important influences on language learning success or failure” (p. 140). Shumin (2012) adds that

[s]peaking a foreign language in public, especially in front of native speakers, is often anxiety-provoking. Sometimes, extreme anxiety occurs when EFL learners become tongue-tied or lost for words in an unexpected situation, which often leads to discouragement and a general sense of failure. (p. 206)

In this paper, the researchers’ personal views are that Korean university students manifest ups and downs within some of those factors in their speech performance, even though they are inclined to believe that the speech delivery is successful when a message is well transmitted by a public speaker using strategies such as storytelling, giving examples, and sharing personal experiences. They are also aware of ethics, proper organization, speech delivery, and verbal and non-verbal communication. Successful presentations increase students’ confidence and motivation to do well in these areas while less successful presentations have the opposite effects on the researcher’s or authors’ experience over students’ performances, and this has been directly observed by the researchers/professors in their actual oral presentations in the classroom. Thus, the areas that were investigated in this paper include anxiety, gestures and facial expressions, voice tone and relaxed attitude and behavior, spontaneity, and planned organization of delivery with the following questions:

1) Do the students’ perceptions match their actual performances?

2) At what rating(s) do their perceptions and actual performances intersect?

The anticipated outcome of this study was to gain pedagogical insights that can guide teachers and students more effectively and efficiently in achieving their goals and objectives in their public speaking classes.

Review of Literature

Factors affecting public speaking

Shepherd and Edelmann (2007) explained that anxiety can be so debilitating before speaking in public that even normal behaviors are affected. Therefore, users can discourage themselves from attempting to communicate or at least limit such speech acts (Choi et al., 2015), which may contribute to anxiety levels and other factors affecting public speaking. Interestingly, Tian (2019) found in his research based on twenty Korean sophomores that “being afraid of making mistakes was not a major source informing their anxiety in Korean students’ classroom presentations” (p. 136).

Research conducted by Ayres et al. (1998, cited in Choi et al., 2014) revealed that “high communicative apprehensions (CAs)in general … use minimal verbal and nonverbal communication …” (p. 26) (see also Daly et al., 1995). In conclusion, Choi et al. (2014) expressed, “[a]s such, it is no surprise that many of the remediation techniques forwarded to mitigate the impact of CA involve imagining the encounter, thereby reducing fear of the unknown” (p. 26) (for review see Bodie, 2010). Minimal verbal and nonverbal communication (such as gestures, facial expressions, posture, and voice tone) happens to be limited due to cultural influences and low proficiency levels based on the researcher’s personal classroom experience in this study. High-context cultures including Eastern cultures such as Korea manifest an explicit message (Hall & Hall 1990; Irwin, 1996) due to harmony and egalitarianism as the preferred communicative strategy (Park, 1993). Besides that, Hong (2003) found that Korean students were considerably more communicatively apprehensive than American students. In other words, Koreans limit their vivid expression of thoughts and emotions through verbal and nonverbal forms of communication due to cultural expectations. To remedy this issue, the contribution of high CA involving imaginary L2 encounters could be considered to lessen the fear of the unknown (Bodie, 2010).

Moreover, voice tone manifests whether or not one is confident in relaying the speech’s message. According to Clayton (2014), “[o]ften, nervousness and anxiety about a speech can be reflected in the tone of your voice or the speed of your speech” (p. 1). These are the non-linguistic manifestations of anxiety exhibited by many students during their presentations and suggest that the following tips should be followed: slow down, breathe, take purposeful pauses, articulation, volume, practice, and record your voice. The plan of a speech to be delivered could also be affected if they are not confident enough to conduct themselves in a public speaking situation. Hincks (2010) discovered that when the students were speaking English, their presentation proficiencies slowed down by 23% compared with the same presentation in a participant’s native language, forcing the speaker to delete some of the content to keep within the time limits. However, a slower rate of speech may be beneficial for EFL audiences, especially for beginner EAP learners (Barrett and Liu, 2016, pp. 1253-1254). Therefore, approaches to addressing such anxiety on the part of presenters should be integrated into presentation classes.

On the other hand, Maclay and Osgood (1959) concluded that “causal phenomena (e.g., umm, hmm, ah), while… often mentioned by linguists, function essentially as non-significant events which may serve to identify linguistically relevant units, such as junctures located at the boundaries of phonemes, morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences” (p. 3). They went on to explain that “faster speakers are better and make significantly fewer hesitation errors” (p. 18) and that “the preferences for different hesitation strategies or markers are part of an individual speaker’s style” (p. 21).

From a presentation standpoint, the speaker’s uncertainty or hesitation also makes the listeners catch up and stresses the less predictable items and the natural-appearing pauses and other hesitation phenomena influence the listener’s connotative judgment of the speaker (e.g., sincerity).

These linguistic aspects of a speech are more difficult for non-native speakers to master but are essential nonetheless for instructors to focus on during presentation training as their students may be judged to be lacking by others who are more proficient in presentation skills than they are. They in turn serve as yet another obstacle for L2 speakers to overcome in becoming proficient public speakers.

Some studies also found that students had difficulty choosing an appropriate topic and making good notes (Yang, 2010) and focused too much on preparing their visuals (Yates & Orlikowski, 2007), or developed an overdependence on themdistorting the communicative purpose of oral presentations (Kuldip & Afida, 2018). However, in the event that they present speech topics with only a speech outline at hand which helps them appear more confident, fluent, spontaneous, and accurate with information, then one can declare that the art of speech delivery is attained.

In relation to the above-mentioned, the overall organization of speech delivery should also be honed. Morse (2011) emphasizes that the introduction should be catchy by attracting the audience’s attention and heightening their curiosity and interest to establish a connection with the audience. Also, connecting with the audience the entire time with goodeye contact helps improve credibility and respect. Establishing a good impression happens as soon as a speaker shows up on stage and gives an introduction. It is recommended that a speaker provide an introduction for less than five minutes without fumbling papers and reading the introduction; instead, simply memorizing it. Moreover, Ramos (2020)believed that the body of the speech should be substantial. This ideal led many more students (32%, good; 30%, average) to organize speeches effectively with various sequential patterns such as comparison-contrast, cause-effect, etc. He believed that

using various idioms, grammatical devices, and comparison methods are instrumental in developing linguistic and communicative skills to achieve a certain level of fluency and accuracy. Without the variety, one may tend to become redundant, with his/her words, structure and content. (p. 89).

Finally, the conclusion should be memorable. Morse (2011) argued that by reinforcing an image and a message, a speaker should leave a strong impression that will inherently bring in a call to action. Finally, she noted that it is also vital that a conclusion should be memorized and delivered with confidence and good eye contact, not longer than the introduction; should wrap up the three main points; and should never end with “okay, that’s it, we’re done” or ask, “any questions?” Yoo and Kaushanskaya (2016) studied the classic finding and found out that, for their 20 Korean-English Bilingual participants, there were

[s]tronger pre-recency effects in the L1 than the L2 suggest[ing] that the Long Term Memory (LTM)…plays a crucial role in the ability to adopt active encoding and retrieval strategies when recalling items from the beginning of the lists. Further, bilinguals’ Working Memory capacity is closely related to recalling items in the pre-recency region in the L1 but not the L2, suggesting that dynamic interactions between the LTM and the Short Term Memory characterize free-recall performance in bilinguals are crucially dependent on bilinguals’ knowledge of their two languages. (p. 11)

This has clear implications for their ability to perform speeches in English when it is their L2. Desai (2016) agrees by stating “[t]he serial position effects can be applied in public speaking where one tries to remember a speech or a script for a play” (p. 302). However, it is also important to keep in mind that despite mastery of the public speaking principles, students or any public speaker would still encounter issues that are involved in the art of speech delivery.

Another concern is pronunciation. It is believed that a speaker’s inaccurate or unclear pronunciation results in a false understanding of information as decoded by listeners. It is important in any type of communication that accurate information should be delivered and processed effectively and efficiently. Jones (2002) emphasized that “creating a stronger link between pronunciation and communication can help increase learner’s motivation by taking pronunciation beyond the lowest common denominator of ‘intelligibility’ and encouraging students’ awareness of its potential as a tool for making their language not only easier to understand but more effective” (p. 183). Ramos (2014c) also mentioned that “[w]hen students have a desirable outcome from people with good accent and diction, some of them are likely to develop or heighten their performance skills in any communicative encounters” (p. 332).

Impact of speech delivery

For Nikitina (2011), a speech delivery is not just a process, act, or art but involves all three. Therefore, it is understood that public speakers should choose a topic, gather information to support their views, organize, and outline their whole speech, and practice expressing a good message while demonstrating fluency, motives, and confidence before an audience. When asking students’ perceptions toward the effectiveness of public speaking in support of their speaking practice, Rahayu’s (2018) study reported that 1) they can help themselves to become confident by practicing speaking; 2) they can improve their potentials and talents effectively; 3) they can express their ideas, opinions, and feelings as they encounter a new experience; 4) they can further improve their vocabulary and fluency; 5) they can solve some issues in public speaking (e.g., nervousness); 6) they can listen more carefully and critically evaluate other speeches; and, 7) they can gain good opportunities for a future career.

Moreover, El Mortaji (2018) conducted a study on the impact of videotaping on the students’ public speaking skills. He found that watching their performances on the videotapes provided the students the avenue to eradicate previous mistakes, explicitly visualize while evaluating the positive and negative aspects of their performances (e.g., verbal and non-verbal). Students also enjoy the experience of watching their performance for the first time, improving their self-confidence, and fostering the alignment of their future goal-oriented speech delivery. Syafryadin et al.’s (2016) study also found out that speech training is beneficial in determining their issues and solving them related to the speaking itself (such as how to open, deliver, close the speech as well as fluency and accuracy in conveying speech in front of a crowd).

Meanwhile, Blume (2013) distinguished between a speech and a presentation in this way: “…a speech is a talk or address, and a presentation is a talk with the use of some sort of visual aid” (para. 5). This distinction puts the speaker as the focus of attention rather than any visual aids they may be using, thus emphasizing the language and strategies used to make an effective speech. Docan-Morgan (2015) emphasized that “[t]he terms public speech and presentation are often used synonymously in everyday language” (p. 5). He said that “[w]hether you speak in public to a large audience or in more intimate contexts with a small audience, the same skills are needed whenever one person has the responsibility for delivering a message successfully to a group of others” (p. 5). Engleberg (2007) noted, “the term speech often connotes a public speech, that is, a presentation to a large public audience…” (2007, p. 1). Therefore, oral presentation and speech delivery share a joint impact in any speaking engagement.

Celce-Murcia (2001) believed that “oral presentation is an activity which improves students’ speaking skill” (p. 17). Meloni and Thompson (1980) claimed that if an oral presentation is taught in the classroom, a language learning experience is meaningful among EFL learners. Researchers have shown that oral presentations can also offer learners an appropriate aid to connect the discrepancy between language study and language use (Farabi et al., 2017).

However, when the students experienced weak competence in public speaking in front of many audiences, the points to remember is that they have insufficient vocabulary and they mispronounce English words, have “nothing to say”, make grammatical mistakes, use inappropriate intonation, experience fear, as well as have inadequate knowledge, poor preparation, and bad time allotment (Nippold et al., 2005). The bottom line of both speech delivery and oral presentation is communicative practice. Ramos’ (2014a) study revealed that Korean students considered any communicative practice a challenge in overcoming inhibitions (e.g., shyness and discomfort), especially when a teacher or an exciting topic provoked them to actively participate. However, even though the topics are interesting, with a lack of practice and skills in gathering and organizing information, a public speaker may not be able to succeed in their communication objectives.

Self-monitoring and self-assessment

Self-monitoring involves self-regulation and is an ongoing process (Harris et al., 2005). It helps students raise awareness of behavioral obstacles to their learning and act to reduce or overcome these by self-monitoring to recognize, manage their own activities, and assess their results. If students achieve a positive outcome, their motivation and efforts to complete tasks will also rise (Falkenberg & Barbetta, 2013). The self-monitoring process must be student-centered thereby leading to independence, motivation, and engagement (Kanani et al., 2017). Self-monitoring offers advantages for both teachers and students. When students are able to self-monitor, required teacher interventions go down and more instructional time results (Bouck et al., 2014; Wolfe et al., 2000).

In terms of self-assessment, research has highlighted various problems connected with the introduction of self-assessment as a tool for evaluation including a lack of correlation between teacher ratings and student self-ratings (Blue, 1988; Pierce et al. , 1993), students’ evaluation experience (Mabe & West, 1982; Ross, 1998), cultural factors (Blanche, 1988; Blue, 1988; Yu & Murphy, 1993), and the assessment instrument itself (global skills assessments appear less reliable than skill or behavior specific forms of self-assessment) (Chapelle & Brindley, 2002; Strong-Krause, 2000).

Second and foreign language learning research demonstrated that students can effectively assess themselves and that moderate to high correlations occur between student self-ratings and others’ evaluations of the same factors or behaviors (Bachman & Palmer, 1989). Some of the most common problems that students without experience in self-assessment may experience are failure to comprehend the assessment process, being too subjective in evaluating their work, and feeling reluctant to do a job they see as belonging to their teacher. Students need to be adequately trained before using such instruments to assess themselves especially if it forms part of the basis for their final grades on assignments or an entire course.

The studies of cultural factors and self-assessment are not conclusive and require more investigation. For instance, Blanche (1988) found that many students did not share the same beliefs regarding evaluation as their instructors, and Oskarsson (1978) concluded a mismatch between learners’ and teachers’ educational goals. Nevertheless, if teachers’ evaluations are regarded as valid and reliable, it is possible to determine the accuracy of their students’ own assessments by comparing their scores (Heilenman, 1991).

The nature of the self-assessment instrument may also affect its reliability for evaluation purposes. When self-assessment instruments ask for global judgments, it may be challenging to interpret the information as evaluations per se. Some studies have demonstrated that when more concrete and descriptive scales are provided, students can assess themselves more accurately (Janssen-van Dieten, 1989; LeBlanc & Painchaud, 1985).

Although there is no consensus on the use of self-assessment for evaluation purposes, it is clear that it is beneficial to learning. First of all, self-assessment fosters autonomy and responsibility for learning. Since self-assessment requires reflection and awareness, learners can control their knowledge and become more independent of the teacher. It has been suggested that self-assessment is an integral part of autonomous learning (Gardner & Miller, 1999; Tudor, 1996) and that without learner self-assessment, “there can be no real autonomy” (Hent et al., 1989, p. 207). Further, when self-assessment expects improvement, genuine autonomy is the result.

Secondly, self-assessment can facilitate critical thinking. As Vygotsky wrote,

self-assessment promotes critical thinking. When teachers allow their students to self-monitor, they foster students’ understanding and management of cognitive processes, and also help them develop knowledge through conscious control over that knowledge or develop metacognitive awareness of knowledge and thought” (Vygotsky, cited in Munoz & Alvarez, 2007, p. 6).

It is essential to teach students metacognitive skills because they lead to the development of better learning skills and performance. According to Chamot and O’Malley (1994), when students are required to self-assess, they need to “exercise a variety of learning strategies and higher-order thinking skills that not only provide feedback to the student but also provide direction for future learning” (p. 119).

Consequently, self-assessment can help students improve learning by recognizing their knowledge and abilities. Reviewing past research helps ascertain what has yet to be discovered to positively and effectively implement self-monitoring and self-assessment within the classroom.

Ultimately, there is disagreement about which factors may affect students’ anxiety while presenting in a classroom setting in front of their peers. This study will limit itself to factors related to anxiety, including gestures and facial expressions, voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior, spontaneity, and planned organization of delivery to better address the needs of students and instructors and incorporate many of the outcomes related to the above literature and findings.

Methodology

Research design

This research used mixed qualitative and quantitative methods. A qualitative method provides open-ended questions which the participants may provide further explanations in the questionnaire. According to Dörnyei (2011), “[t]he open responses can offer graphic examples, illustrative quotes, and can also lead us to identify issues not previously anticipated” (p. 107).

Role of researchers

With regards to the role of researchers in a study, “[p]ositionality, in qualitative research, refers to the researcher’s stance in relation to significant others in the research and how such a viewpoint influences the dynamics of the research process and the writing of the research paper” (Ellis & Bochner, 2000). The foreign researchers in this study are professors, and at the same time, the observers in the class, and thus their personal experiences are deeply embedded in the research process. Therefore, the researcher cannot “hide behind the cloak of alleged neutrality (Fine et al. , 2000, p. 109).

Description of participants

The study was conducted with the participation of all third- and fourth-year English majors who attended the Public Speaking classes offered by the researchers within three semesters at the Department of English Language and Literature under the College of Humanities of a Korean university. Specifically, there were 47student participants in the survey. Participation in the study was completely voluntary. Students were assured that non-participation would not affect their grades.

Data collection procedures

All data gathering in this study was done through a questionnaire with five questions concerning students’ perception of their speech delivery. Each question was marked following the five points Likert scale (i.e.,, excellent (5), good (4), average (3), fair (2), and poor (1)) and was accompanied by a statement of a possible reason which each student marked as ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ (see appendix A). The possible reasons were indicated for the students to agree with and to guide them on what and how to reason out. A space below was also provided for each question, just in case, students may have further explanations or other reasons that were not covered by the questionnaire. Several students who provided other reasons were also included.

All students rated all questions and indicated in response to the prepared possible reasons whether they agreed; however, not all of them wrote down additional reasons. Furthermore, student respondents agreed to take a video of their actual performances, and they were the ones who sent their videos to their professors via email. The actual performance and the questionnaire were graded using the public speaking rubric.[1]

Data analysis

Frequency count to determine the number of responses in the survey questionnaire was calculated by the percentage formula in Excel (The Smart Method, 2018). The five questions or aspects) in the survey questionnaire were then arranged as follows: anxiety, gestures and facial expressions, voice tone and relaxed attitude and behavior, spontaneity, and planned organization of delivery. The quantitative survey results were interpreted in light of the qualitative results from the students’ reasons and the researcher-professors’ comments or analysis. In the end, SPSS was used to for data analysis with a result chi-sq coefficient and p-value that shows whether there is significance between students’ self-evaluation and actual delivery (professors’ evaluation of their classroom performances with recorded videos).

Results

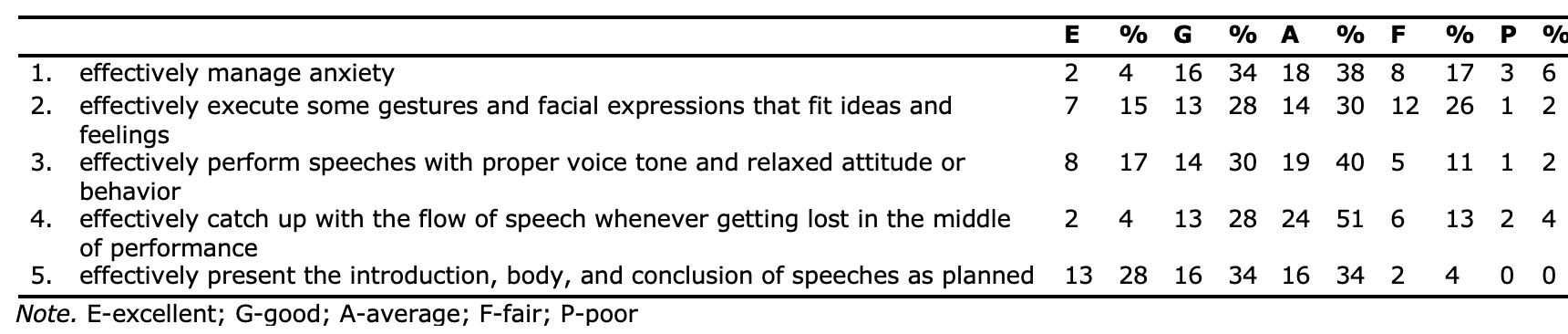

Table 1 below presents the results of student respondents concerning their perceptions of speech delivery.

Table 1: Percentage of students’ perception in speech delivery

In reporting how effectively they managed anxiety, about 2/3 of the students rated themselves as average, good, and excellent: Of the 47 participants, 4% reported that they effectively or excellently managed it, 34% reported that they were good at it, and 38% felt that they were average. On the other hand, 17% of them rated themselves as fair, and 6% thought they were poor. With confidence, 13 student participants expressed their insights as they know their strengths and weaknesses, thus managing anxiety in speech delivery. For example, student AW commented: “While doing many activities and tests, I trained myself to be a more natural speaker. “Student G mentioned: “If I feel nervous, I gaze a person among audience [sic] For sure, I have my strategies to overcome nervousness or anxiety.” Student AT admitted: “I am not afraid of speaking in front of others originally. However, if I didn’t prepare well, I would feel nervous and show up my nervousness [sic]”. Taking on the challenge, student AS stressed: “I pushed myself to lots of challenging experiences, so I just let me nervous [sic].” Because when I give a speech, I’m always nervous. “ Student AR said: “I am nervous easily when I present but I can adapt easily too. “

In contrast, Student AU mentioned: “I’m still nervous though I’m perfectly ready for it, “ and this was agreed to by student AV. Student I said: “Actually, I’m not accustomed to stand in front of people. I have to practice more. “Student B said: “. . . because I can’t control my mind well [sic].”

As for determining how effectively they executed some gestures and facial expressions that fit ideas and feelings, about 2/3 of the 47 participants evaluated their performance as average, good, and excellent. Specifically, 15% of them felt that they excellently executed some gestures and facial expressions that fit their ideas and feelings, 28% perceived themselves as good, and 30% felt they were average; while 26% felt they were at the fair rating, 2% were at the poor level. To support these claims, 19 participants revealed that most of their performance was driven by “ethical speaking”. For instance, student AV added: “I can use body language in speech and I can hide my nervousness on my face [sic]”. Student AT agreed by saying: “After taking ethical speaking, I add more gestures when I deliver my speech. But it is hard for me to show my facial expression fitting my speech [sic].”However, while this is not perhaps ethical: student AQ said: “Yes. Also, I can do well when I drink. I feel my emotions are more rich [sic]. “

In finding out how they effectively performed speeches with proper voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior, more than 2/3 of the 47 participants labeled themselves as average, good, and excellent. In particular, 17% of the participants were excellent at performing their speeches with proper voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior, 30% felt that they were at the good rating, and 40% perceived that they performed at the average level. The rest (11% being fair and 2% being poor) felt they were at the lowest ratings. According to 22 participants, they have developed creativity and confidence that help them perform with satisfaction. Some of their comments are as follows: Student M confidently said: “. . . I like to sing a song and I know which tone of voice is proper for each sentence. Those things are my important strategies. “Student AG reasoned: “Because I practiced enough to perform my speech perfectly. “Student AR said: “. . . if I don’t act for people, they feel uncomfortable so I have to try. “ However, student AD mentioned: “I need more skill to speak slowly. “

In revealing how they effectively caught up with the flow of speech whenever getting lost in the middle of a performance, over 2/3 of the 47 participants rated themselves average, good, and excellent. In detail, 4% of student participants thought they were excellent at it, 28%considered themselves as good, and 51% were at the average rating. The rest (13% and 4%) assessed themselves as fair and poor, respectively. The prevalent reason for this claim by 20 participants was that they had accumulated the essential strategy of coping mechanisms. For example, student AV claimed: “My crisis management skill is good. I’ll continue my speech in short time [sic].” However, student AS honestly mentioned: “It’s hard because I think I’m trying to memorize it too much. I have to speak like I do normally, but it’s difficult.” Also, student N said: “I feel hard to get back to my speech when I lost my way [sic]” and student J confirmed that he also encountered the same feeling.

In laying out how they effectively presented the introduction, body, and conclusion of speeches as planned, most of them rated themselves as good, average, and excellent: Of the 47 participants, 28% were excellent at presenting the introduction, body, and conclusion of speeches as planned, 34% were good, and another 34% felt they were at the average rating. Only 4% rated themselves as fair and none of them (0%) felt they were poor at it. This suggests that most of them were able to carry it out satisfactorily. Twenty-two of the total number of participants revealed that it is because they have mastered the flow of speech. For instance, student AQ confidently said: “Yes, of course! I learned a lot in the last few years with professors.” Student M commented: “Yes. I believe everything is up to introduction and conclusion part. Entice audience in the introduction, and inspire them in the conclusion with a strong impression are the one of the most important thing in my speech [sic]”. Student P said: “Sometimes, it is difficult because it is in English. ‘actual’ speech performance via videos.”[2]

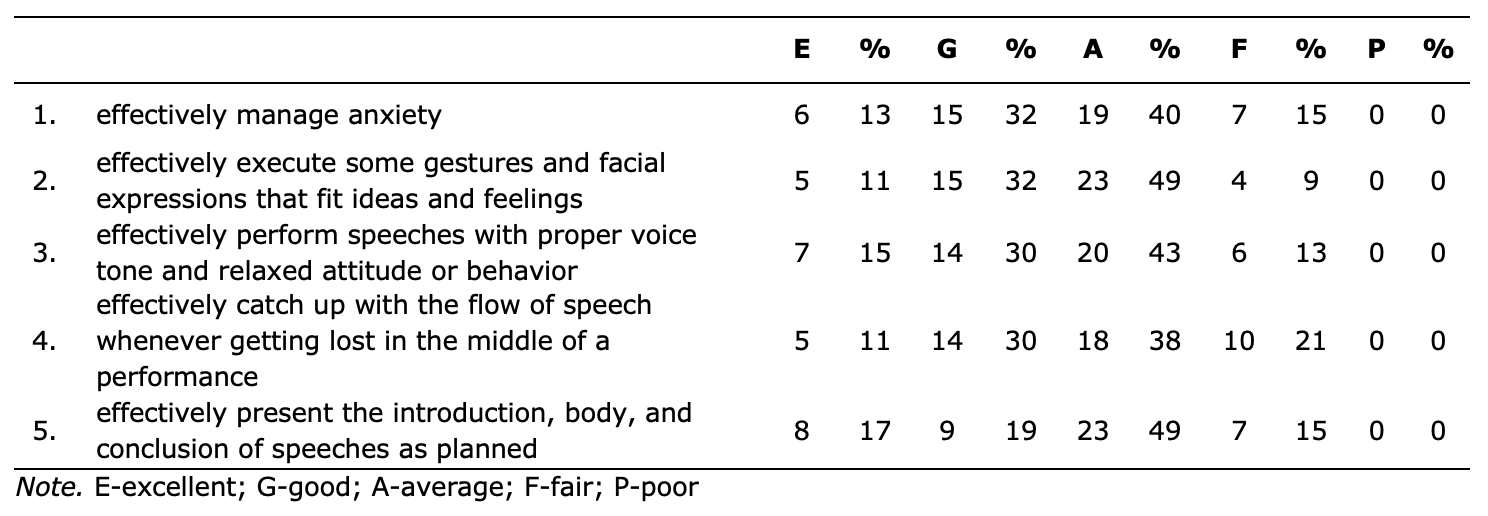

Table 2: Percentage of students’ actual speech delivery (professors’ observation via videos)

In managing anxiety effectively, 13% of 47 student participants were rated as excellent; 32%, good; 40%, average; 15%, fair; 0%, poor. In executing some gestures and facial expressions effectively that fit ideas and feelings, the ratings evaluated by the researcher-professors are the following: 11% of them were excellent; 32%, good; 49%, average; 9%, fair; 0%, poor. As for performing speeches effectively with proper voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior, 15% were marked excellent; 30% were good; 43%, average; 13%, fair; 0%, poor. Moreover, student participants’ ability tocatch up effectively with the flow of speech whenever getting lost in the middle of a performances as follows:11% were rated as excellent; 30%, good; 38%, average; 21%, fair; 0%, poor. Finally, presenting the introduction, body, and conclusion of speeches effectively as planned, 17% of the 47 participants were rated as excellent; 19%, good; 49%, average; 15%, fair; 0%, poor.

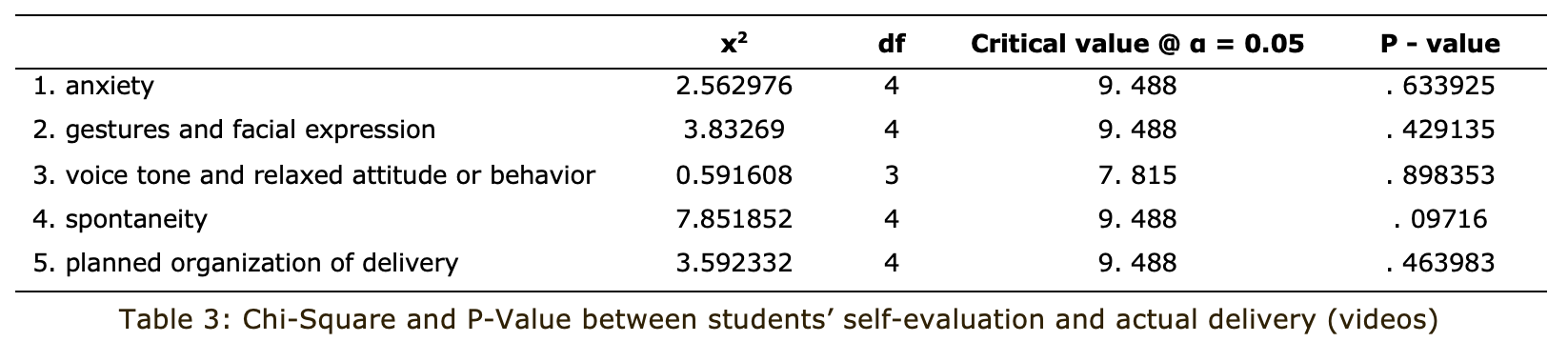

Table 3 presents the chi-square and p-value between students’ perception of their speech delivery and their actual speech performance, as shown in their videos.

Table 3: Chi-Square and P-Value between students’ self-evaluation and actual delivery (videos)

The difference between students’ self-evaluations and actual delivery in terms of anxiety, gestures and facial expression, voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior, spontaneity, and planned organization of delivery was not significant in any facet. The results of those five aspects are not significant at p < .05. Also, the critical values are more significant than the chi-square values.

Discussion

In this study, participants performed moderately in the public speaking tasks. In particular, a good number of student participants were able to effectively manage anxiety due to self-monitoring or self-assessment. Knowing their own strengths and weaknesses potentially helps build up a framework for anxiety management. For instance, undergoing various classroom activities and tests, gazing intently at audience members, and accepting readiness are some ways to effectively scaffold their speech delivery. In addition, self-awareness also anticipates and potentially helps managefuture threats and opportunities. One of these involves pushing oneself into challenging experiences wherein they would tend to become anxious or nervous because they have not yet established confidence standing in front of the crowd or may have inhibitions due to their cultural orientation. Typically, Korean students feel that their society, culturally speaking, is too judgmental and sensitive; so even with minor mistakes, it takes time for them to cope with their minds or emotions. In other words, they may focus too much on these concerns until they would eventually feel down resulting in feelings of failure even if only minor mistakes are being made. This makes it harder for them to overcome their fear of public speaking in the target language.

As ethical speaking is indeed influential for students, many of them were still able to effectively execute some gestures and facial expressions that fit their ideas and feelings. For instance, a good facial expression could hide their true level of anxiety or nervousness, which suggests that body language expressed through facial expressions and other forms of gestures make a speech performance more attractive and memorable. Besides, drinking alcohol could stimulate enriched emotions, which may be a part of ethical speaking as long as it does not create trouble in the delivery process. Based on general observations, drinking in Korea is culturally a part of social and business undertakings, which measure the amount of success as an intimate relationship is built in the process. That is why drinking (not to the extent of drunkenness, though) could be a tool to feel more confident, hoping that a teacher could understand the effort to perform.

Proper voice tone and innate traits which are classified into attitude or behavior, are essential elements in establishing good public speaking performance. Attitude is the hidden mindset of an individual, while behavior is the visual aspect performed through actions and words. Used together, most of the student participants effectively carried out speeches with the proper tone of voice and a relaxed attitude or behavior due to the development of creativity and confidence. Creativity can be seen developing as one sings a song to determine a varied tone of voice which affects natural speech; thus confidence and self-esteem can be developed as they succeed in the art of speech delivery. In addition, confidence is the initial effect of an effort to perfect a speech, which would mean that the proper attitude (e.g., sensitivity or empathy) overcomes obstacles. In fact, one student tried to do everything possible to avoid feeling the audience members’ discomfort.

Another aspect of speech delivery dwells upon most students who were able to use spontaneity, i.e.,, effectively catching up with the flow of speech whenever getting lost in the middle of the performance. In such a scenario, the students have already accumulated the essential strategy of applying a coping mechanism to sustain their performance in the actual delivery of a speech. A coping mechanism refers to a mental or psychological system that evaluates the degree of inconvenience or uncomfortable situation sand converts them into positive outcomes in whichever way is most suitable to the individual. It seems that when they have encountered life crises, they are able to manage difficult times that naturally induce an automatic response to a new challenging task on the spot (e.g., able to continue the speech after a short period of feeling lost in the middle of actual performance). On the other hand, when one performs by relying on memorization in the entire speech delivery, they are likely to fail in remembering what to say next because of a lack of authentic immersion in a practical situation. Mostly, Korean students at lower levels or years were taught to study English by memorizing what is written in the book without appropriate conversational practice as most of them are not willing or able to interact with foreigners and their fellows orally.

Finally, as a planned organization is important in delivery, many student respondents were able to present the introduction, body, and conclusion of the speech as planned. Indeed, they have mastered the flow of speech due to their previous language classroom experiences. Further, what is more appealing in their speech delivery is that one could not forget the special tricks for introduction and conclusion that encapsulate the overall mood or direction of the speech performance. This progress suggests that the teacher’s teaching skills and input should be significant to a learner’s academic life so that motivation and interest keep developing every time new learning takes place. Educators must also make students fully aware of the criteria of speech delivery with their skills which can be further honed by applying all the lessons to their actual speech performances. However, it is of utmost importance that when students fall short of good speech delivery, educators should understand and look into the difficulties students encounter in English classes and their personal issues and efficiently implement scaffolding techniques to enable students to achieve their students’ academic goals.

Conclusion

In the five factors of their public speaking performances, there are no significant values or differences statistically between students’ perceptions as indicated in the questionnaire and actual delivery as observed by the researcher-professors using the videos. In effect, the students performed moderately well. However, professors should still consider the student perspective in shaping instruction to offer guidance in developing compensatory strategies or approaches that support effective public speaking. At the end of the semester, professors should take note of the data gathered from students to reshape the public speaking syllabus. By doing so, most students will increase their public speaking performance to a good or excellent rating.

Self-monitoring or self-assessment referring to students’ strengths and weaknesses are essential in carrying out public speaking performances. However, anxiety is sometimes present due to their cultural orientation that pertains to their often judgmental and sensitive society that inhibits their confidence. However, the professors of public speaking in this study believe that they could be trained with sufficient practice. According to DeCapua and Wintergerst (2010), “[a]lthough a culture shapes its members, people within any culture differ from one another…[and]members of a culture remain individuals in their own right” (p. 42). Therefore, opportunities could be offered in the form of constant practice and personal strategies inside and outside of the classroom (e.g., developing the right attitude or perspective towards commitment and challenges) to improve their public speaking. After all, human beings can adapt to realize their full potential.

Techniques for hiding anxiety include gestures and facial expressions. However, performance-based criteria are not the only way to improve public speaking skills. It is also a lecture-based curriculum that affects a student’s meaningful experience of how public speaking principles lead them to potentially achieve better outcomes. DeCapua and Wintergerst (2010) noted that “. . . each culture has its own specific nonverbal behaviors, which can be misunderstood or misinterpreted by members of other cultures who interpret these nonverbal behavior patterns according to the rules and norms of their own culture” (p. 71). In other words, they may be distracted by foreign professors (or any foreign audience members) or their classmates who were present during their actual performance. Professors, in turn, need to remember that the lens through which they view such performances may be influenced by their cultural norms. Thus, the development of a student’s schema through a series of lectures and training influences the overall control of actual performance and delivery strategies in the use of gestures and facial expressions. As part of the strategy system, minimal alcohol drinking may also help students to complete the tasks, but that could also be risky and an example of a possibly negative coping strategy if overused.

In boosting creativity and confidence, the proper usages of both voice tone and relaxed attitude or behavior are the keys. Most of them care so much about other people’s views, regardless of whether they grew up in a collective or individualistic society. For example, Kim (2002) noted, “[p]roblems arise when certain cultural practices are imposed on people who do not share the cultural values behind the practices” (p. 839). Thus, teachers in public speaking classes should develop consistency in achieving specific goals, one of which could be to speak moderately and clearly.

Moral lessons from their interpersonal experience with situations and people help public speaking learners to manage spontaneity and fluency throughout the speech just as they have strengthened their positive attitudes to survive in difficult moments. Due to this positive attitude and knowledge of their full experience, they can become more spontaneous and attentive during their speeches in English. Shumin (2012) concluded that “. . . to speak a language, one must know how the language is used in a social context” (p. 206). On the other hand, when one performs by relying on memorization in the entire speech delivery, they are likely to fail in remembering what to say next because of a lack of authentic immersion. Thus, memorization does not last long because the information is superficially registered in the brain without meaningful language experience. Oliver and Utermohlen (1995) criticize the fact that students are often made to memorize information without processing it critically.

Finally, for the planned organization of delivery, teachers should give enough input and train them with skills that are significant to them so that their competence, motivation, and interest could be improved. Ramos (2015) study pointed out that “some Korean students in the FGDs became open-minded to critical thinking activities because they could widen their logical thinking capacity by organizing their thoughts or information with proper words and grammar” (p. 57). Targeting something that they have strong opinions about is important to draw out critical thinking that leads them to become more communicative (Ramos, 2014b).

The outcome of this paper is a reminder that reassessment of course objectives and goals of the public speaking class should be done at the end of each term or semester so that while reflecting on their teaching skills and course materials, teachers can address the real strengths and weaknesses of students.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Prof. Ricky F. Dancel for helping us with the Table 3 statistical procedure and Prof. Juan Camarena for the Spanish translation in the abstract section. Finally, Ramos would like to thank Lee Junrim (Sean) for the inspiration to finish this paper.

References

Ayres, J., Heuett, B., & Sonandre, D. A. (1998). Testing a refinement in an intervention for communication apprehension. Communication Reports, 11(1), 73–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08934219809367687

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1989). The construct validation of self-ratings of communicative language ability. Language Testing, 6(1), 14-25. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F026553228900600104

Barrett, N. E., & Liu, G. Z. (2016). Global trends and research aims for English academic oral presentations: Changes, challenges, and opportunities for learning technology. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1227–1271.https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316628296

Blanche, P. (1988). Self-assessment of foreign language skills: Implications for teachers and researchers. RELC Journal, 19(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003368828801900105

Blue, G. M. (1988). Self-assessment: The limit of learner independence. In A. Brookes & P. Grundy (Eds.), Individualization and autonomy in language learning. (ELT Documents 131), pp. 100-118. The British Council.

Blume, J. (2013, 11 March). Speech vs. presentation: What’s the difference? BrightCarbon [Blog]. https://www.brightcarbon.com/blog/speech-vs-presentation

Bodie, G. D. (2010). A racing heart, rattling knees, and ruminative thoughts: Defining and explaining public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 59(1), 70–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634520903443849

Bouck, E. C., Savage, M., Meyer, N. K., Taber-Doughty, T., & Hunley, M. (2014). High tech or low tech? Comparing self-monitoring systems to increase task independence for students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(3), 156-167. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1088357614528797

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Language teaching approaches: An overview. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (3rd Ed.). Heinle & Heinle.

Chamot, A. U., & O’Malley, J. M. (1994). The CALLA Handbook: Implementing the cognitive language learning approach. Addison Wesley.

Chapelle, C. A., & Brindley, G. (2002). Assessment. In N. Schmitt (Ed.), An introduction to applied linguistics, (pp. 267-288). Arnold.

Choi, C. W., Honeycutt, J. M., & Bodie, G. D. (2015). Effects of imagined interactions and rehearsal on speaking performance, Communication Education, 64(1), 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2014.978795

Clayton, D. (2014, 23 November). Business presentations: Voice tone and speed of speech [Blog. Presentation skills coaching, public speaking & communication training. https://simplyamazingtraining.co.uk/blog/business-presentations-voice-tone-speed-speech

Daly, J. A., Vangelisti, A. L., & Weber, D. J. (1995). Speech anxiety affects how people prepare speeches: A protocol analysis of the preparation processes of speakers. Communication Monographs, 62, 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759509376368

DeCapua, A., & Wintergerst, A. C. (2010). Crossing cultures in the language classroom. The University of Michigan Press.

Desai, D. (2016). The significance of mode of presentation on the serial position effect: An exploratory study. Indian Journal of Mental Health 2016, 3(3). https://www.indianmentalhealth.com/pdf/2016/vol3-issue3/Original_research_article_8.pdf

Docan-Morgan, T. (2015). The benefits and necessity of public speaking education. In K. Vaidya (Ed.), Public speaking for the curious: Why study public speaking, Curious Academic. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0ByUSqH2mXhyPemFDeU5FOVdsMmM/view?usp=sharing

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Edwards, P. N. (1998, 2008). How to give an academic talk. [Power Point Presentation]. Retrieved from https://intra.nscl.msu.edu/gradresources/files.php

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexibility. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

El Mortaji, L. (2018). University students’ perceptions of videotaping as a teaching tool in a public speaking course. European Scientific Journal, 14(8). https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n8p102

Falkenberg , C. A., & Barbetta P. M. (2013). The effects of a self-monitoring package on homework completion and accuracy of student with disabilities in an inclusive general education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22(3), 190-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9169-1

Farabi, M., Hassanvand, S., & Gorjian, B. (2017). Using guided oral presentation in teaching English language learners’ speaking skills. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, 3(1): 17-24. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.jalll.20170301.03

Fine, M., Weis, L., Weseen, S., & Wong, L. (2000). For whom? Qualitative research, representations, and social responsibilities. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (1990). Understanding cultural differences. Intercultural Press.

Harris, K. R., Friedlander, B. D., Saddler, B., Frizzelle, R., & Graham, S. (2005). Self-monitoring of attention versus self-monitoring of academic performance: Effects among students with ADHD in general education classroom. The Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 145- 156. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00224669050390030201

Heilenman, L. K. (1990). Self-assessment of second language ability: The role of response effects. Language Testing, 7(2), 174-201, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F026553229000700204

Hong, J. (2003). A cross-cultural comparison of the relationship between ICA, ICMS and assertiveness/cooperativeness tendencies[Conference presentation]. Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association: Communication in Borderlands, San Diego, CA.

Hunt, J., Gow, L., & Barnes, P. (1989). Learner self-evaluation and assessment: A tool for autonomy in the language learning classroom. In V. Bickley (Ed.), Language teaching and learning styles within and across cultures (pp. 207-217). Institute of Language in Education.

Irwin, H. (1996). Communicating with Asia: Understanding people with customs. Allen & Unwin.

Janssen-van Dieten, A.-M. (1989). The development of a test of Dutch as a second language: The validity of self-assessment by inexperienced subjects. Language Testing, 6(1), 30-46. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/026553228900600105

Jones, R. H. (2002). Beyond ‘listen and repeat’: Pronunciation teaching materials and theories of second language acquisition. In C. J. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 178-187). Cambridge University Press.

Kanani, Z., Adibsereshki, N., Haghoo, H. A. (2017). The effect of self-monitoring training on the achievement motivation of students with dyslexia. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(3), 430-439. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1310154

Kim, H. S. (2002). We talk therefore we think? A cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 828-842. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.828

Kuldip, K., & Afida, M. A. (2018). Exploring the genre of academic oral presentations: A critical review. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature. 7(1), 152-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.1p.152

LeBlanc, R., & Painchaud, G. (1985). Self-assessment as a second language placement instrument. TESOL Quarterly, 19(4), 673-687.https://doi.org/10.2307/3586670

Mabe, P. A., & West, S. G. (1982). Validity of self-evaluation of ability: A review and meta- analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), 280-296. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.280

Maclay, H., & Osgood, C. E. (1959). Hesitation phenomena in spontaneous English speech, Word, 15(1), 19-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1959.11659682

Meloni, C., & Thompson, S. (1980). Oral reports in the intermediate ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 14(4), 503-510.

Morse, H. (2011, 18 May). Creating and organizing your speech [Blog]. http://legalwatercoolerblog.com/2011/05/18/creating-and-organizing-your-speech

Munoz, A., & Alvarez, M. E. (2007). Students’ objectivity and perception of self assessment in an EFL classroom. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 4(2), 1-25, Summer 2007. http://www.asiatefl.org/main/download_pdf.php?i=297&c=1419313753&fn=4_2_01.pdf

Nikitina, A. (2011). Successful public speaking. Bookboon.com

Nippold, M. A., Hesketh, L. J., Duthie, J. K., & Mansfield, T.C.(2005).Conversational versus expository discourse: A study of syntactic development in children, adolescents, and adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 48(5), 1048-64. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/073)

Oliver, H., & Utermohlen, R. (1995). An innovative teaching strategy: Using critical thinking to give students a guide to the future [ED389701], ERIC. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED389702.pdf

Oskarsson, M. (1978). Approaches to self-assessment in foreign language learning. Council of Europe.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House.

Park, M.-S. (1993). Communication styles in two different cultures: Korean and American. Han Shin.

Pierce, B. N., Swain, M., & Hart, D. (1993). Self-assessment, French immersion, and locus of control. Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/14.1.25

Rahayu, E. (2018). Students’ perception toward the effectiveness of public speaking class to support their speaking practice [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Makassar Muhammadiyah University. https://digilibadmin.unismuh.ac.id/upload/5734-Full_Text.pdf

Ramos, I. D. D. (2014a). Communicative activities: Issues on pre, during, and post challenges in Korea’s English education. International Journal of Education Learning and Development, 2(1), 1-16. https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Communicative-Activities-Issues-On-Pre-During-and-Post-Challenges-In-South-Koreas-English-Education1.pdf

Ramos, I. D. D. (2014b). The English majors’ expectations, experiences, and potentials: Inputs toward Korea’s globalization. International Journal of English Language Education, 2(1), 157-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/ijele.v2i1.4963

Ramos, I. D. D. (2014c). The openness to cultural understanding by using western films: Development of English language learning. International Journal of Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering, 9(1), 327-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijmue.2014.9.5.33

Ramos. I. D. D. (2015). The expectations, experiences, and potentials of English majors: Basis for curriculum development training program toward Korea’s globalization. LAP Lambert Academic.

Ramos, I. D. D. (2020). Public speaking preparation stage: Critical thinking and organization skills in South Korea. International Research in Education, 8(2), 77-96. https://doi.org/10.5296/ire.v8i2.17541

Ross, S. (1998). Self-assessment in second language testing: A meta-analysis and analysis of experiential factors. Language Testing, 15(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F026553229801500101

Shepherd, R.-M., & Edelmann, R. J. (2007). Social phobia and the self-medication hypothesis: A case study approach. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 20(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070701571756

Shumin, K. (2012). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 204-211). Cambridge University Press.

Strong-Krause, D. (2000). Exploring the effectiveness of self-assessment strategies in ESL placement. In G. V. Ekbatani, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Learner-directed assessment in ESL (pp. 255-278), Lawrence Erlbaum.

Syafryadin, Nurkamto, J., Linggar, A. D., & Mujiyanto, J. (2016). Students’ perception toward the implementation of speech training. International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 3(6). https://www.ijires.org/administrator/components/com_jresearch/files/publications/IJIRES_719_FINAL.pdf

The Smart Method. (2018). Excel versions explained. https://thesmartmethod.com/excel-versions-explained

Tian, C. (2019). Anxiety in classroom English presentations: A case study in Korean tertiary educational context. Higher Education Studies, 9(1), 132-143. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v9n1p132

Tudor, I. (1996). Learner-centeredness as language education. Cambridge University Press.

Wolfe, L. H., Heron, T. E., & Goddard, Y. L. (2000). Effects of self-monitoring on the on-task behavior and written language performance of elementary students with learning disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 10(1), 49-73.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016695806663

Yang, L. (2010). Doing a group presentation: Negotiations and challenges experienced by five Chinese ESL students of commerce at a Canadian university. Language Teaching Research, 14(2), 141-160. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362168809353872

Yates, J., & Orlikowski, W. (2007). The Power Point Presentation and its corollaries: How genres shape communicative action in organizations. Journal of the Language Teacher, 21(4), 256-277.

Yoo, J.. & Kaushanskaya, M. (2016). Serial-position effects on a free-recall task in bilinguals. Memory, 24(3), 409–422. https://doi. org/10.1080/09658211.2015.1013557

Yu, J., & Murphy, K. R. (1993). Modesty bias in self-ratings of performance: A test of the cultural relativity hypothesis. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 357-363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00878.x

[1] Modified from: http://www.tusculum.edu/research/documents/PublicSpeakingCompetencyRubric.pdf?

[2] Again, see rubric at: http://www.tusculum.edu/research/documents/PublicSpeakingCompetencyRubric.pdf?